Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

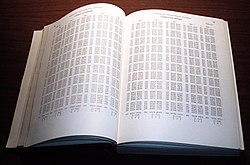

Mathematical table

View on WikipediaMathematical tables are tables of information, usually numbers, showing the results of a calculation with varying arguments. Trigonometric tables were used in ancient Greece and India for applications to astronomy and celestial navigation, and continued to be widely used until electronic calculators became cheap and plentiful in the 1970s, in order to simplify and drastically speed up computation. Tables of logarithms and trigonometric functions were common in math and science textbooks, and specialized tables were published for numerous applications.

History and use

[edit]The first tables of trigonometric functions known to be made were by Hipparchus (c.190 – c.120 BCE) and Menelaus (c.70–140 CE), but both have been lost. Along with the surviving table of Ptolemy (c. 90 – c.168 CE), they were all tables of chords and not of half-chords, that is, the sine function.[1] The table produced by the Indian mathematician Āryabhaṭa (476–550 CE) is considered the first sine table ever constructed.[1] Āryabhaṭa's table remained the standard sine table of ancient India. There were continuous attempts to improve the accuracy of this table, culminating in the discovery of the power series expansions of the sine and cosine functions by Madhava of Sangamagrama (c.1350 – c.1425), and the tabulation of a sine table by Madhava with values accurate to seven or eight decimal places.

Tables of common logarithms were used until the invention of computers and electronic calculators to do rapid multiplications, divisions, and exponentiations, including the extraction of nth roots.

Mechanical special-purpose computers known as difference engines were proposed in the 19th century to tabulate polynomial approximations of logarithmic functions – that is, to compute large logarithmic tables. This was motivated mainly by errors in logarithmic tables made by the human computers of the time. Early digital computers were developed during World War II in part to produce specialized mathematical tables for aiming artillery. From 1972 onwards, with the launch and growing use of scientific calculators, most mathematical tables went out of use.

One of the last major efforts to construct such tables was the Mathematical Tables Project that was started in the United States in 1938 as a project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), employing 450 out-of-work clerks to tabulate higher mathematical functions. It lasted through World War II.[2]

Tables of special functions are still used. For example, the use of tables of values of the cumulative distribution function of the normal distribution – so-called standard normal tables – remains commonplace today, especially in schools, although the use of scientific and graphing calculators as well as spreadsheet and dedicated statistical software on personal computers is making such tables redundant.

Creating tables stored in random-access memory is a common code optimization technique in computer programming, where the use of such tables speeds up calculations in those cases where a table lookup is faster than the corresponding calculations (particularly if the computer in question doesn't have a hardware implementation of the calculations). In essence, one trades computing speed for the computer memory space required to store the tables.

Trigonometric tables

[edit]Trigonometric calculations played an important role in the early study of astronomy. Early tables were constructed by repeatedly applying trigonometric identities (like the half-angle and angle-sum identities) to compute new values from old ones.

A simple example

[edit]To compute the sine function of 75 degrees, 9 minutes, 50 seconds using a table of trigonometric functions such as the Bernegger table from 1619 illustrated above, one might simply round up to 75 degrees, 10 minutes and then find the 10 minute entry on the 75 degree page, shown above-right, which is 0.9666746.

However, this answer is only accurate to four decimal places. If one wanted greater accuracy, one could interpolate linearly as follows:

From the Bernegger table:

- sin (75° 10′) = 0.9666746

- sin (75° 9′) = 0.9666001

The difference between these values is 0.0000745.

Since there are 60 seconds in a minute of arc, we multiply the difference by 50/60 to get a correction of (50/60)*0.0000745 ≈ 0.0000621; and then add that correction to sin (75° 9′) to get :

- sin (75° 9′ 50″) ≈ sin (75° 9′) + 0.0000621 = 0.9666001 + 0.0000621 = 0.9666622

A modern calculator gives sin(75° 9′ 50″) = 0.96666219991, so our interpolated answer is accurate to the 7-digit precision of the Bernegger table.

For tables with greater precision (more digits per value), higher order interpolation may be needed to get full accuracy.[3] In the era before electronic computers, interpolating table data in this manner was the only practical way to get high accuracy values of mathematical functions needed for applications such as navigation, astronomy and surveying.

To understand the importance of accuracy in applications like navigation note that at sea level one minute of arc along the Earth's equator or a meridian (indeed, any great circle) equals one nautical mile (approximately 1.852 km or 1.151 mi).

Tables of logarithms

[edit]

Tables containing common logarithms (base-10) were extensively used in computations prior to the advent of electronic calculators and computers because logarithms convert problems of multiplication and division into much easier addition and subtraction problems. Base-10 logarithms have an additional property that is unique and useful: The common logarithm of numbers greater than one that differ only by a factor of a power of ten all have the same fractional part, known as the mantissa. Tables of common logarithms typically included only the mantissas; the integer part of the logarithm, known as the characteristic, could easily be determined by counting digits in the original number. A similar principle allows for the quick calculation of logarithms of positive numbers less than 1. Thus a single table of common logarithms can be used for the entire range of positive decimal numbers.[4] See common logarithm for details on the use of characteristics and mantissas.

History

[edit]In 1544, Michael Stifel published Arithmetica integra, which contains a table of integers and powers of 2 that has been considered an early version of a logarithmic table.[5][6][7]

The method of logarithms was publicly propounded by John Napier in 1614, in a book entitled Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Descriptio (Description of the Wonderful Rule of Logarithms).[8] The book contained fifty-seven pages of explanatory matter and ninety pages of tables related to natural logarithms. The English mathematician Henry Briggs visited Napier in 1615, and proposed a re-scaling of Napier's logarithms to form what is now known as the common or base-10 logarithms. Napier delegated to Briggs the computation of a revised table. In 1617, they published Logarithmorum Chilias Prima ("The First Thousand Logarithms"), which gave a brief account of logarithms and a table for the first 1000 integers calculated to the 14th decimal place. Prior to Napier's invention, there had been other techniques of similar scopes, such as the use of tables of progressions, extensively developed by Jost Bürgi around 1600.[9][10]

The computational advance available via common logarithms, the converse of powered numbers or exponential notation, was such that it made calculations by hand much quicker.

See also

[edit]- Abramowitz and Stegun Handbook of Mathematical Functions

- BINAS, a Dutch science handbook

- Difference engine

- Ephemeris

- Group table

- Handbook

- History of logarithms

- Nautical almanac

- Matrix

- MAOL, a Finnish handbook for science

- Multiplication table

- Numerical analysis

- Random number table

- Ready reckoner

- Reference book

- Rubber book Handbook of Chemistry & Physics

- Standard normal table

- Table (information)

- Truth table

- Jurij Vega

References

[edit]- ^ a b J J O'Connor and E F Robertson (June 1996). "The trigonometric functions". Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ^ Grier, David Alan (1998). "The Math Tables Project of the Work Projects Administration: The Reluctant Start of the Computing Era". IEEE Ann. Hist. Comput. 20 (3): 33–50. doi:10.1109/85.707573. ISSN 1058-6180.

- ^ Abramowitz and Stegun Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Introduction §4

- ^ E. R. Hedrick, Logarithmic and Trigonometric Tables (Macmillan, New York, 1913).

- ^ Stifelio, Michaele (1544), Arithmetica Integra, London: Iohan Petreium

- ^ Bukhshtab, A.A.; Pechaev, V.I. (2001) [1994], "Arithmetic", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press

- ^ Vivian Shaw Groza and Susanne M. Shelley (1972), Precalculus mathematics, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, p. 182, ISBN 978-0-03-077670-0

- ^ Ernest William Hobson (1914), John Napier and the invention of logarithms, 1614, Cambridge: The University Press

- ^ Folkerts, Menso; Launert, Dieter; Thom, Andreas (2016), "Jost Bürgi's method for calculating sines", Historia Mathematica, 43 (2): 133–147, arXiv:1510.03180, doi:10.1016/j.hm.2016.03.001, MR 3489006, S2CID 119326088

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Jost Bürgi (1552 – 1632)", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Campbell-Kelly, Martin (2003), The history of mathematical tables: from Sumer to spreadsheets, Oxford scholarship online, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-850841-0

External links

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- LOCOMAT : A census of mathematical and astronomical tables.

Mathematical table

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Purpose

Core Concept

A mathematical table consists of a precomputed array of values representing the output of a mathematical function for a discrete set of inputs, typically organized in a grid or list format to display pairs such as for selected values of . These tables provide ready-to-use numerical results derived from explicit calculations of the function, enabling quick reference without recomputing each instance.[8] In contrast to general data tables, which compile observational or empirical datasets such as census statistics or experimental measurements, mathematical tables focus exclusively on the deterministic evaluation of mathematical functions, ensuring reproducibility and precision for analytical purposes.[9] Common examples of tabulated basic functions include square roots, where values like are listed for successive integers ; reciprocals, offering to avoid division; and factorials, computing for small positive integers up to a practical limit. These selections prioritize functions encountered frequently in arithmetic and algebraic computations. The core utility of mathematical tables lies in minimizing repetitive computational effort, for instance, by obviating the need to perform successive multiplications when determining powers like through lookup rather than iteration. Before electronic calculators became widespread, such tables formed the backbone of manual numerical work across scientific and engineering fields.[10][8]Historical Role in Computation

Mathematical tables originated in ancient civilizations as essential aids for computation, with Babylonian clay tablets from around 1800 BCE containing tables of squares, square roots, reciprocals, and other arithmetic values to facilitate practical calculations in trade, land measurement, and administration.[11] These early compilations, inscribed on durable clay, demonstrated a systematic approach to precomputing results, reducing the need for repetitive manual arithmetic in daily and scholarly tasks.[12] Later, Greek and Indian scholars advanced this tradition; notably, the Indian mathematician Aryabhata included a sine table in his Aryabhatiya (499 CE), providing 24 values for trigonometric functions to support astronomical predictions and timekeeping. During the Renaissance, mathematical tables gained prominence in navigation and astronomy, driven by Europe's expanding maritime exploration. The 15th-century German astronomer Regiomontanus (Johannes Müller) compiled extensive trigonometric tables, including sines and tangents, which were crucial for solving spherical problems in celestial navigation and calendar reform.[13] His work, published posthumously in 1533, marked a shift toward more precise and accessible computational tools, influencing subsequent European table-making efforts.[14] The 17th and 18th centuries saw a proliferation of logarithmic tables, revolutionizing computation in science and engineering. Henry Briggs introduced common logarithms in his Arithmetica Logarithmica (1624), providing values to 14 decimal places for numbers from 1 to 20,000 and 90,001 to 100,000, which simplified multiplication and division.[15] Adriaan Vlacq extended this in 1627 with the first complete table of decimal logarithms from 1 to 100,000, enhancing accuracy for astronomical and surveying applications.[16] In late 18th-century France, the revolutionary government, later under Napoleonic influence, funded major table projects, such as Gaspard de Prony's 1790s initiative to compute extensive logarithmic and trigonometric tables using a division of labor among 60 to 90 human computers, supported by substantial funding equivalent to five times a typical academic salary.[4] By the 19th and early 20th centuries, mathematical tables reached their peak as indispensable tools in engineering, physics, and computation, with large-scale compilations integrating into scientific practice. The Royal Society and the British Association for the Advancement of Science established committees, such as the Mathematical Tables Committee (active from 1871), to produce and verify comprehensive volumes, including tables of Bessel functions and other special functions essential for mechanics and electromagnetism.[4] These efforts, often involving international collaboration, ensured high accuracy and reliability, underscoring tables' role as the backbone of pre-digital scientific calculation until the mid-20th century.[17]Major Types

Logarithmic Tables

Logarithmic tables consist of precomputed values of common logarithms (base 10) designed to simplify multiplication, division, and exponentiation by converting them into addition, subtraction, and related operations. The logarithm of a product equals the sum of the logarithms, as expressed by the formula Each entry in such tables is structured with a characteristic, the integer part indicating the order of magnitude, and a mantissa, the fractional part providing the significant digits; tables typically list only the mantissas for numbers from 1 to 10,000 or more (up to 100,000 in comprehensive editions), with the characteristic determined separately by the number of digits in the argument.[18][1][16] The invention of logarithmic tables is credited to John Napier, who published the first set in 1614 in his Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Descriptio, initially using a natural base but laying the groundwork for computational aids. Henry Briggs refined this in 1617 by adopting base-10 logarithms, publishing the initial table of common logs in Logarithmorum Chilias Prima, which made the values more intuitive for decimal-based arithmetic. Adriaan Vlacq further advanced the field in 1628 with Arithmetica Logarithmica, providing the first complete table of 10-decimal-place logarithms for numbers from 1 to 100,000, building directly on Briggs's work and serving as the foundation for subsequent editions.[19][16][20] In practice, these tables facilitated operations like multiplication: for 23.4 × 56.7, locate log(23.4) ≈ 1.3692 and log(56.7) ≈ 1.7536 in the table, add to get 3.1228, then find the antilog (or number corresponding to that logarithm) ≈ 1,327 to yield the product. Division follows similarly using subtraction, since log(a/b) = log a - log b, while exponentiation leverages multiplication of logs. For values not directly tabulated, linear interpolation between entries provides approximations.[21][22] Historically, logarithmic tables revolutionized computations in astronomy, where they shortened laborious multiplications for orbital calculations, and in surveying, enabling efficient solutions to trigonometric triangles over vast distances. Pierre-Simon Laplace noted that logarithms "doubled the life of an astronomer" by reducing calculation time. Early tables, however, contained errors; William Gardiner's influential 1742 edition, Tables of Logarithms, for All Numbers from 1 to 102,100, was prized for its accuracy but included numerous discrepancies, such as unit errors in specific entries, prompting later corrections by mathematicians like J. W. L. Glaisher in systematic error analyses.[23][24]Trigonometric Tables

Trigonometric tables trace their origins to the 2nd century CE with Claudius Ptolemy's Almagest, which featured a table of chords for a circle of radius 60 parts, effectively approximating sine values for central angles from 0.5° to 180° in half-degree increments using geometric constructions based on inscribed regular polygons and linear interpolation.[25][26] This innovation built on earlier Babylonian sexagesimal methods and provided a foundational tool for astronomical and geometric computations, with chord lengths related to sines via the formula chord(θ) = 2 sin(θ/2).[25] Advancing this tradition, Georg Joachim Rheticus published Canon doctrinæ triangulorum in 1551, introducing the first comprehensive set of tables covering all six trigonometric functions—sine, cosine, tangent, cotangent, secant, and cosecant—defined directly from right-triangle ratios, computed to high precision for angles up to 90° and extending to full circles through symmetry.[27] Rheticus's work, supported by detailed algorithms for verification, marked a shift toward systematic tabulation that facilitated broader applications in surveying and astronomy, influencing subsequent tables like those in his larger posthumous Opus Palatinum de triangulis.[27] Historically, trigonometric tables structured values by angle measures, predominantly in degrees from 0° to 90° (with extensions via co-functions), in increments as fine as 0.1° to enable accurate linear interpolation for intermediate angles; radians appeared later as an alternative unit tied to arc length.[28][25] Natural tables listed direct function values, while logarithmic variants tabulated their common logarithms to streamline multiplicative operations in complex calculations.[29] A representative natural sine table illustrates basic structure and utility:| θ (°) | sin(θ) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 30 | 0.5 |

| 45 | |

| 60 | |

| 90 | 1 |

Multiplicative and Divisive Tables

Multiplicative and divisive tables encompass basic arithmetic aids designed for performing multiplication, division, squares, and reciprocals, serving as foundational tools for everyday calculations in pre-modern societies. These tables facilitated rapid integer operations without relying on complex algorithms, making them essential for merchants, scribes, and educators. Unlike more advanced logarithmic or trigonometric tables, they focused on straightforward numerical products and quotients, often limited to small ranges to support mental or manual computation. The origins of these tables trace back to ancient civilizations. In Egypt around 1650 BCE, the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, copied by the scribe Ahmes, included multiplication tables based on doubling methods and a comprehensive 2/n table for unit fractions to aid division, demonstrating early systematic approaches to arithmetic problems.[32] Similarly, Babylonian scribes from the second millennium BCE compiled reciprocal tables in base-60 notation to simplify division by converting it to multiplication by the inverse, with entries for numbers up to 81 whose reciprocals terminated neatly.[33] The Romans adapted these concepts through portable abacus devices, which featured grooves and beads to represent multiplication and division operations efficiently, reducing computation time for trade and engineering tasks.[34] Standard formats of multiplicative tables emerged in duodecimal systems, commonly extending to 12×12 grids to align with measurements like 12 inches in a foot or 12 pence in a shilling, though some variants reached 20×20 for broader utility.[35] Square tables listed values from 1² to 100², providing quick access to perfect squares for applications in geometry and accounting. Divisive tables often took the form of reciprocals, offering decimal approximations such as 1/7 ≈ 0.142857 or 1/9 ≈ 0.111111 to enable division via multiplication, particularly useful for non-terminating fractions.[33] In educational settings, these tables promoted memorization to build proficiency in mental arithmetic, allowing users to recall facts like 7×8=56 instantly for problem-solving.[35] For instance, a basic 12×12 multiplication table might appear as follows:| × | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 24 |

| 3 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 21 | 24 | 27 | 30 | 33 | 36 |

| 4 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 16 | 20 | 24 | 28 | 32 | 36 | 40 | 44 | 48 |

| 5 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | 40 | 45 | 50 | 55 | 60 |

| 6 | 6 | 12 | 18 | 24 | 30 | 36 | 42 | 48 | 54 | 60 | 66 | 72 |

| 7 | 7 | 14 | 21 | 28 | 35 | 42 | 49 | 56 | 63 | 70 | 77 | 84 |

| 8 | 8 | 16 | 24 | 32 | 40 | 48 | 56 | 64 | 72 | 80 | 88 | 96 |

| 9 | 9 | 18 | 27 | 36 | 45 | 54 | 63 | 72 | 81 | 90 | 99 | 108 |

| 10 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 | 110 | 120 |

| 11 | 11 | 22 | 33 | 44 | 55 | 66 | 77 | 88 | 99 | 110 | 121 | 132 |

| 12 | 12 | 24 | 36 | 48 | 60 | 72 | 84 | 96 | 108 | 120 | 132 | 144 |

Construction Techniques

Manual Calculation Methods

Manual calculation of mathematical tables relied on systematic algorithms and extensive human effort, predating mechanical aids and emphasizing iterative techniques for polynomials, logarithms, and trigonometric functions. One foundational approach involved the method of finite differences, which allowed human computers to generate tables of polynomial functions by computing successive differences from initial values, avoiding direct evaluation of higher powers. This technique, rooted in Newtonian interpolation, was applied manually to construct tables for functions like cubes or higher-degree polynomials, where differences of constant order simplified the process into arithmetic operations. Charles Babbage's Difference Engine, conceived in 1822, automated this method but drew directly from established manual practices used by computers to tabulate polynomials efficiently.[37][38] For logarithmic tables, John Napier computed his logarithmic tables using iterative geometric progressions starting from 10^7 and decreasing by small ratios (such as 0.9999999), with corresponding logarithms increasing arithmetically in multiple sequences to cover the range. This method, detailed in his 1614 work Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Descriptio, involved extensive manual approximations over 20 years, laying the groundwork for later logarithm computations.[39][40] Napier's approach enabled the construction of logarithm tables by applying the procedure repeatedly to generate values for numbers up to a desired range, often verified through cross-multiplication checks. Trigonometric tables were similarly built through iterative application of angle addition formulas, leveraging known values for standard angles to derive others. For instance, to find , the difference formula is used with and , yielding . Computers extended such calculations across grids of angles, often in degrees or radians, by chaining formulas for sums or differences to fill tables with sines, cosines, and tangents to multiple decimal places. This method, formalized in works like Regiomontanus's 15th-century tables, required careful arithmetic to propagate values systematically.[41] The labor involved in these methods was immense, typically involving teams of human computers who performed divisions of labor: some calculated primary values, others verified intermediates, and all cross-checked for consistency. A prominent example is Gaspard de Prony's project in the 1790s, where over 80 workers—many unemployed hairdressers trained for the task—computed extensive logarithmic and trigonometric tables for the French Cadastre, producing manuscripts spanning 19 volumes through coordinated manual arithmetic over several years. This factory-like organization, inspired by Adam Smith's division of labor, underscored the scale of human computation needed for accurate, comprehensive tables before mechanical alternatives emerged.[42][43]Error Control and Interpolation

Sources of error in mathematical tables primarily stemmed from rounding during manual calculations and the propagation of inaccuracies through iterative computational methods, such as finite differences or power series expansions used to generate successive entries. These errors could accumulate, leading to systematic deviations in later table values. A notable historical example occurred in mid-19th-century Britain, where Robert Shortrede's logarithmic tables, published in 1849, contained multiple calculation and typographical errors that affected their reliability for navigation and engineering applications; these were systematically identified and listed in later astronomical publications.[44][45] To mitigate and detect such errors, table compilers and verifiers relied on rigorous checking procedures, including cross-verification with inverse functions—such as computing the antilogarithm of a logarithmic entry to ensure it reconstructs the original number—or performing independent recomputations of subsets of entries using alternative algorithms. These methods helped identify discrepancies before publication, though they were labor-intensive and not always comprehensive.[46] Interpolation extended the utility of mathematical tables by allowing estimation of function values at points between tabulated entries, thereby reducing the need for denser tables while maintaining reasonable accuracy. For small intervals, linear interpolation was commonly applied, approximating the value aswhere and are adjacent tabulated points with . This method sufficed for many practical purposes in historical computations, such as navigation. For greater precision over larger intervals, higher-order techniques like Lagrange interpolation were employed, constructing a polynomial that passes exactly through multiple tabulated points to estimate intermediate values more accurately.[47] Precision standards for mathematical tables typically aimed for 7 to 10 decimal places in the final entries, balancing computational feasibility with practical utility in fields like astronomy and surveying. To achieve this, computations often incorporated guarded digits—extra figures beyond the intended precision—to buffer against rounding errors during intermediate steps, ensuring the final rounded values remained faithful to the true function. This practice was essential in manual table production, where even minor rounding discrepancies could propagate.[46][45]