Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mimeograph

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on the |

| History of printing |

|---|

|

A mimeograph machine (often abbreviated to mimeo, sometimes called a stencil duplicator or stencil machine) is a low-cost duplicating machine that works by forcing ink through a stencil onto paper.[1] The process is called mimeography, and a copy made by the process is a mimeograph.

Mimeographs, along with spirit duplicators and hectographs, were common technologies for printing small quantities of a document, as in office work, classroom materials, and church bulletins. For even smaller quantities, up to about five, a typist would use carbon paper. Early fanzines were printed by mimeograph because the machines and supplies were widely available and inexpensive. Beginning in the late 1960s and continuing into the 1970s, photocopying gradually displaced mimeographs, spirit duplicators, and hectographs.

Origins

[edit]Use of stencils is an ancient art, but – through chemistry, papers, and presses – techniques advanced rapidly in the late nineteenth century:

Papyrograph

[edit]A description of the Papyrograph method of duplication was published by David Owen:[2]

A major beneficiary of the invention of synthetic dyes was a document reproduction technique known as stencil duplicating. Its earliest form was invented in 1874 by Eugenio de Zuccato, a young Italian studying law in London, who called his device the Papyrograph. Zuccato's system involved writing on a sheet of varnished paper with caustic ink, which ate through the varnish and paper fibers, leaving holes where the writing had been. This sheet – which had now become a stencil – was placed on a blank sheet of paper, and ink rolled over it so that the ink oozed through the holes, creating a duplicate on the second sheet.

The process was commercialized[3][4] and Zuccato applied for a patent in 1895 having stencils prepared by typewriting.[5]

Electric pen

[edit]Thomas Edison received US patent 180,857 for Autographic Printing on August 8, 1876.[6] The patent covered the electric pen, used for making the stencil, and the flatbed duplicating press. In 1880, Edison obtained a further patent, US 224,665: "Method of Preparing Autographic Stencils for Printing," which covered the making of stencils using a file plate, a grooved metal plate on which the stencil was placed which perforated the stencil when written on with a blunt metal stylus.[7]

The word mimeograph was first used by Albert Blake Dick[8] when he licensed Edison's patents in 1887.[9]

Dick received Trademark Registration no. 0356815 for the term mimeograph in the US Patent Office. It is currently[as of?] listed as a dead entry, but shows the A.B. Dick Company of Chicago as the owner of the name.

Over time, the term became generic and is now an example of a genericized trademark.[10] (Roneograph, also Roneo machine, was another trademark used for mimeograph machines, the name being a contraction of Rotary Neostyle.)

Cyclostyle

[edit]

In 1891, David Gestetner patented his Automatic Cyclostyle. This was one of the first rotary machines that retained the flatbed, which passed back and forth under inked rollers. This invention provided for more automated, faster reproductions since the pages were produced and moved by rollers instead of pressing one single sheet at a time.

By 1900, two primary types of mimeographs had come into use: a single-drum machine and a dual-drum machine. The single-drum machine used a single drum for ink transfer to the stencil, and the dual-drum machine used two drums and silk-screens to transfer the ink to the stencils. The single drum (example Roneo) machine could be easily used for multi-color work by changing the drum – each of which contained ink of a different color. This was spot color for mastheads. Colors could not be mixed.

The mimeograph became popular because it was much cheaper than traditional print – there was neither typesetting nor skilled labor involved. One individual with a typewriter and the necessary equipment became their own printing factory, allowing for greater circulation of printed material.

-

Advertisement from 1889 for the Edison Mimeograph

-

A wooden Edison's mimeograph size 12"

-

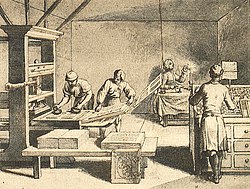

1918 illustration of a mimeograph machine

-

Jackson & O'Sullivan's "The National" Duplicator. Produced in Brisbane, Queensland during World War II.

-

Mimeograph machines used by the Belgian resistance during World War II to produce underground newspapers and pamphlets

Mimeography process

[edit]The image transfer medium was originally a stencil made from waxed mulberry paper. Later this became an immersion-coated long-fiber paper, with the coating being a plasticized nitrocellulose. This flexible waxed or coated sheet is backed by a sheet of stiff card stock, with the two sheets bound at the top.

Once prepared, the stencil is wrapped around the ink-filled drum of the rotary machine. When a blank sheet of paper is drawn between the rotating drum and a pressure roller, ink is forced through the holes on the stencil onto the paper. Early flatbed machines used a kind of squeegee.

The ink originally had a lanolin base[11] and later became an oil in water emulsion. This emulsion commonly uses turkey-red oil (sulfated castor oil) which gives it a distinctive and heavy scent.

Preparing stencils

[edit]One uses a regular typewriter, with a stencil setting, to create a stencil. The operator loads a stencil assemblage into the typewriter like paper and uses a switch on the typewriter to put it in stencil mode. In this mode, the part of the mechanism which lifts the ribbon between the type element and the paper is disabled so that the bare, sharp type element strikes the stencil directly. The impact of the type element displaces the coating, making the tissue paper permeable to the oil-based ink. This is called "cutting a stencil".[12]

A variety of specialized styluses were used on the stencil to render lettering, illustrations, or other artistic features by hand against a textured plastic backing plate.[13]

Mistakes were corrected by brushing them out with a specially formulated correction fluid, and retyping once it has dried. (Obliterine was a popular brand of correction fluid in Australia and the United Kingdom.)[14]

Stencils were also made with a thermal process, an infrared method similar to that used by early photocopiers. The common machine was a Thermofax.[15]

Another device, called an electrostencil machine, sometimes was used to make mimeo stencils from a typed or printed original. It worked by scanning the original on a rotating drum with a moving optical head and burning through the blank stencil with an electric spark in the places where the optical head detected ink. It was slow and produced ozone. Text from electrostencils had lower resolution than that from typed stencils, although the process was good for reproducing illustrations. A skilled mimeo operator using an electrostencil and a very coarse halftone screen could make acceptable printed copies of a photograph.

During the declining years of the mimeograph, some people made stencils with early computers and dot-matrix impact printers.[16]

Limitations

[edit]Unlike spirit duplicators (where the only ink available is depleted from the master image), mimeograph technology works by forcing a replenishable supply of ink through the stencil master. In theory, the mimeography process could be continued indefinitely, especially if a durable stencil master were used (e.g. a thin metal foil). In practice, most low-cost mimeo stencils gradually wear out over the course of producing several hundred copies. Typically the stencil deteriorates gradually, producing a characteristic degraded image quality until the stencil tears, abruptly ending the print run. If further copies are desired at this point, another stencil must be made.

Often, the stencil material covering the interiors of closed letterforms (e.g. a, b, d, e, g, etc.) would fall away during continued printing, causing ink-filled letters in the copies. The stencil would gradually stretch, starting near the top where the mechanical forces were greatest, causing a characteristic "mid-line sag" in the textual lines of the copies, that would progress until the stencil failed completely.

The Gestetner Company (and others) devised various methods to make mimeo stencils more durable.[17]

Compared to spirit duplication, mimeography produced a darker, more legible image. Spirit duplicated images were usually tinted a light purple or lavender, which gradually became lighter over the course of some dozens of copies. Mimeography was often considered "the next step up" in quality, capable of producing hundreds of copies. Print runs beyond that level were usually produced by professional printers or, as the technology became available, xerographic copiers.

Durability

[edit]Mimeographed images generally have much better durability than spirit-duplicated images, since the inks are more resistant to ultraviolet light. The primary preservation challenge is the low-quality paper often used, which would yellow and degrade due to residual acid in the treated pulp from which the paper was made. In the worst case, old copies can crumble into small particles when handled. Mimeographed copies have moderate durability when acid-free paper is used.[18]

Contemporary use

[edit]Gestetner, Risograph, and other companies still make and sell highly automated mimeograph-like machines that are externally similar to photocopiers. The modern version of a mimeograph, called a digital duplicator, or copyprinter, contains a scanner, a thermal head for stencil cutting, and a large roll of stencil material entirely inside the unit. The stencil material consists of a very thin polymer film laminated to a long-fiber non-woven tissue. It makes the stencils and mounts and unmounts them from the print drum automatically, making it almost as easy to operate as a photocopier. The Risograph is the best known of these machines.[citation needed]

Although mimeographs remain more economical and energy-efficient in mid-range quantities, easier-to-use photocopying and offset printing have replaced mimeography almost entirely in developed countries.[citation needed] Mimeography continues to be used in some developing countries because it is a simple, cheap, and robust technology. Many mimeographs can be hand-cranked, requiring no electricity.

Uses and art

[edit]Mimeographs and the closely related but distinctly different spirit duplicator process were both used extensively in schools to copy homework assignments and tests. They were also commonly used for low-budget amateur publishing, including club newsletters and church bulletins. They were especially popular with science fiction fans, who used them extensively in the production of fanzines in the middle 20th century, before photocopying became inexpensive.

Letters and typographical symbols were sometimes used to create illustrations, in a precursor to ASCII art. Because changing ink color in a mimeograph could be a laborious process, involving extensively cleaning the machine or, on newer models, replacing the drum or rollers, and then running the paper through the machine a second time, some fanzine publishers experimented with techniques for painting several colors on the pad.[19]

In addition, mimeographs were used by many resistance groups during World War Two as a way to print illegal newspapers and publications in countries such as Belgium.[20]

In the NCIS Season 7 episode, "Power Down", agents McGee and DiNozzo bring a mimeograph up from the basement. McGee derisively comments, "Yeah, now all we need is a dinosaur who knows how to use it." before Agent Gibbs simply uses the device to make a number of replicants of a composite sketch. As the rest of the team looks on in amazement, Gibbs angrily shoulders past McGee.

See also

[edit]- Duplicating machines

- Gocco

- List of duplicating processes

- Mimeoscope

- Mimeo Revolution

- Spirit duplicator (also known as a "Rexograph" or "Ditto machine" in the US or a "Banda machine" in the UK)

References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of MIMEOGRAPH". www.merriam-webster.com.

- ^ Owen, David (2004). Copies in Seconds. Simon & Schuster. p. 42. ISBN 0-7432-5117-2 – via Google book preview.

- ^ 1878: Library Journal 3:390 Advertisement via Google Books

- ^ Antique Copying Machines from Office Museum

- ^ Eugenic de Zuccato (1895) Patent US548116 Improvement for stencils from typewriting

- ^ US 180857, Edison, Thomas A., "Improvement in autographic printing", issued August 8, 1876

- ^ US 224665, Edison, Thomas A., "Method of Preparing Autographic Stencils for Printing", issued February 17, 1880

- ^ Dick (A.B.) Co. "Circular Edison Mimeograph". Thomas A. Edison Papers at Rutgers University. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ Dick (A.B.) Co. "Agreement, Thomas Alva Edison, Dick (A.B.) Co". Thomas A. Edison Papers at Rutgers University. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ "mimeograph. The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000". Archived from the original on September 8, 2008.

- ^ Mimeograph Ink Vehicle Formula Archived 2012-07-09 at archive.today Chemical Industry

- ^ "How to prepare a mimeograph stencil by using a typewriter". LinguaLinks Library. SIL International. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ "How to prepare a mimeograph stencil by hand". LinguaLinks Library. SIL International. Archived from the original on October 22, 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ "How to correct a mimeograph stencil". LinguaLinks Library. SIL International. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ "Preservation Self-Assessment Program (PSAP) | Office Printing and Reprography". psap.library.illinois.edu. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- ^ "How to prepare a mimeograph stencil by using a dot matrix printer". LinguaLinks Library. SIL International. Archived from the original on February 13, 2008. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ "Duplicating stencil". Patentstorm. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- ^ US 5270099, "Thermal mimeograph paper", issued December 21, 1990

- ^ Rich Brown (June 26, 2006). "Dr. Gafia's Fan Terms – VICOLOR". The FANAC Fan History Project. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Stone, Harry (1996). Writing in the Shadow: Resistance Publications in Occupied Europe (1st ed.). London: Cass. ISBN 0-7146-3424-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Hutchison, Howard (1979). Mimeograph Operation, Maintenance & Repair. Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Tab Books. ISBN 9780830689415. OCLC 4136051.

External links

[edit]Mimeograph

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Precursors to Mimeography

Prior to the development of practical stencil duplication in the late 19th century, document replication relied on labor-intensive mechanical and chemical methods driven by expanding administrative needs in business and government. James Watt patented the letter copying press in 1780, a device that used dampened tissue paper pressed against inked originals to transfer text via mechanical pressure, enabling up to 100 copies but limited to flatbed operation and requiring immediate use of fresh ink.[5] Carbon paper, introduced in the early 1800s, allowed simultaneous duplication during handwriting or typing by transferring ink via pressure, though it produced faint, reversed copies on the back side and was unsuitable for large runs.[6] The hectograph emerged around 1869 as a low-cost chemical alternative, involving writing on paper with aniline dye, transferring the soluble dye to a gelatin slab, and then pressing blank sheets against the slab to yield 50 to 100 purple-tinted copies before fading.[7] This method, also known as jellygraph, supported handwriting or simple drawings but degraded quickly due to gelatin saturation and dye diffusion, restricting it to short-run applications like school worksheets or small offices.[8] Its limitations in copy volume and clarity highlighted the need for more durable, scalable techniques, particularly for typescript. Direct precursors to stencil-based mimeography appeared in the 1870s with manual perforation methods. In 1874, Italian law student Eugenio de Zuccato patented the Papyrograph (or Trypograph), the first documented stencil duplicator, which used a metal stylus to scratch text or drawings into a waxed paper stencil supported on a perforated tablet, allowing ink to pass through the incisions onto multiple sheets via a squeegee or brush.[9][10] This process enabled facsimile reproduction of up to several dozen copies but was tedious for extended text due to hand-perforation fatigue and imprecise hole alignment, primarily suiting illustrations or brief manuscripts rather than high-volume office duplication.[11] Zuccato's innovation established the core principle of ink-forced-through-stencil printing, addressing hectograph's impermanence while foreshadowing mechanized improvements in perforation efficiency.[12]Edison's Electric Pen and Early Patents

Thomas Edison developed the electric pen during the summer and fall of 1875 at his Menlo Park laboratory, aiming to create a low-cost method for duplicating documents through stencil perforation.[13] The device consisted of a handheld pen powered by a small electric motor that drove a reciprocating needle, puncturing wax-coated Japanese tissue paper to form a stencil as the user wrote or drew.[14] This perforation allowed ink to pass through onto underlying sheets when the stencil was mounted in a flatbed press and rolled with an ink applicator.[15] Edison filed a patent application for the invention on March 13, 1876, receiving U.S. Patent No. 180,857 for "Improvement in Autographic Printing" on August 8, 1876, which encompassed both the electric pen and the duplicating press mechanism.[15] The patent described the system's operation: the pen's needle, oscillating at high speed, created uniform holes in the stencil without tearing, enabling the production of multiple identical copies via manual inking.[16] Edison marketed the complete outfit, including the pen, press, and supplies, for approximately $30, making it accessible for office and small-scale use.[17] A related patent, U.S. No. 224,665, issued to Edison on February 17, 1880, refined the method of preparing autographic stencils, addressing improvements in stencil durability and ink transfer efficiency.[1] These early patents established the core principles of stencil duplication, predating widespread commercialization and influencing subsequent devices like the mimeograph, though initial adoption was limited by the pen's vibration and electrical requirements.[18] Edison claimed a single stencil could yield up to 5,000 copies under optimal conditions, demonstrating the technology's potential for scalable reproduction.[17]Commercial Advancements and Standardization

Following Thomas Edison's 1876 patent for autographic stencils and duplicating press, commercial development accelerated through licensing agreements. In 1884, Albert B. Dick, founder of the A.B. Dick Company established in Chicago the prior year, improved upon Edison's stencil design by developing a more practical wax-coated version suitable for typewriter use.[19] Dick licensed Edison's patents in 1887, coining the term "mimeograph" and launching production under the Edison-Dick brand, which propelled the technology from experimental to market-ready.[20] The A.B. Dick Company introduced the Model 0 flatbed duplicator in 1887, priced at $12, making mimeography accessible for offices, schools, and small businesses.[2] This model, along with subsequent iterations like the No. 51 automatic version produced from 1898 to 1905, featured standardized components such as interchangeable stencils and ink drums, facilitating reliable operation and maintenance.[21] By the early 20th century, A.B. Dick had become the world's largest mimeograph manufacturer, with their equipment recognized as the standard duplicating device across commercial, educational, and religious sectors due to consistent quality and widespread availability of supplies.[22] Advancements included refinements in stencil preparation and machine durability; for instance, stencils evolved with uniform markings and backing materials tailored to specific models, ensuring compatibility and reducing errors in high-volume runs.[23] These developments, driven by A.B. Dick's iterative patents and production scaling, standardized mimeograph processes, enabling up to thousands of copies per stencil and cementing its role as a cost-effective alternative to letterpress printing until offset lithography gained prominence in the mid-20th century.[3]Technical Operation

Stencil Preparation Methods

Stencil preparation for mimeography begins with a master sheet consisting of a thin, wax-impregnated tissue paper fronted by a protective backing sheet and sometimes a cushion layer to absorb impact. The objective is to selectively remove or perforate the wax coating to form microscopic apertures corresponding to the desired text, images, or lines, enabling ink to pass through during duplication. This process requires precision to ensure uniform porosity without tearing the delicate tissue, which typically measures around 0.002 inches thick.[24] The foundational method, patented by Thomas Edison on February 17, 1880, involves manually pressing the stencil tissue against a pointed stylus or style to displace wax and create impressions or apertures. US Patent No. 224,665 describes this autographic technique, where the pointed instrument indents the wax surface, forming channels for ink without fully penetrating the sheet, allowing for handwritten or drawn originals. Edison's electric pen, an electromagnetic perforator operating at high speed, mechanized this process by rapidly puncturing the stencil, producing up to 5,000 viable copies from a single master in early applications.[25][26] By the early 20th century, typewriting became the dominant preparation technique for text-heavy stencils, adapting standard typewriters via a "stencil" or "no-ribbon" setting that disengages the ink ribbon, enabling the typebars to strike the wax directly and cut character-shaped holes. Operators typed the content onto the stencil placed over the platen, with the typeface edges scraping away wax to form the image; closed-loop letters like 'o' or 'b' often required manual bridging or correction fluid to prevent ink flooding. A.B. Dick Company manuals from the mid-20th century instructed removing the backing cushion post-typing to inspect and correct the master before mounting.[27][28] Hand-cutting with a stylus supplemented typing for illustrations, signatures, or corrections, where a fine-pointed tool scraped wax from the tissue over a textured surface like a file plate or screen to guide even removal. This method allowed artistic flexibility but demanded skill to avoid irregularities that could cause smudging or uneven inking in runs exceeding 1,000 copies.[24] Later variants introduced thermal preparation in the 1950s, using infrared heat from devices like the Thermofax to transfer images from originals onto heat-sensitive stencils, perforating via differential wax melting; however, this remained less common for standard mimeographs compared to mechanical methods until spirit duplicators overshadowed mimeography.[29]Duplication Mechanism and Ink Delivery

The duplication mechanism in early mimeographs, as patented by Thomas Edison in US Patent 180,857 issued on August 8, 1876, employed a flatbed press where a perforated stencil was placed over copy paper, and ink was applied via a felt roller or press to force it through the stencil holes onto the sheets below.[30] [5] This process enabled production rates of 4-5 copies per minute, with stencils yielding up to 1,000 impressions before requiring replacement.[5] Commercial rotary drum machines, developed from the late 1880s onward, superseded flatbed designs for greater speed and volume. The stencil wraps around a cylindrical drum containing or lined with ink; as the drum rotates—manually via crank or electrically—a feed mechanism advances blank paper between the drum and an opposing pressure roller.[1] [5] The roller applies firm pressure, squeezing ink through the stencil's perforations to replicate the image on the paper in direct contact.[1] Ink delivery relies on the drum's internal saturation or an automatic feed system distributing viscous, quick-drying aniline dye—typically purple for visibility—uniformly across the stencil's backing.[1] In single-drum configurations, ink flows freely from the reservoir through the mesh-backed stencil under roller pressure; dual-drum variants use a silk screen belt tensioned between cylinders, with auxiliary rollers metering ink to prevent excess or uneven application.[1] This setup minimized waste while sustaining output of 1,500 or more copies per stencil in optimized models.[5]Machine Variants and Operation

Mimeograph machines function by pressing ink through perforations in a stencil onto blank paper, producing duplicate copies. The core mechanism involves securing a prepared stencil—typically waxed stencil paper with cut holes forming text or images—around an ink-filled drum or on a flatbed platen. In operation, the drum or platen distributes ink via an internal pad or rollers, and as paper is fed against the stencil, ink transfers selectively through the openings under pressure from a backing roller. Early models relied on manual inking and pressing, while later designs automated ink distribution and paper advancement for efficiency.[1][3] Initial variants were flatbed duplicators, such as the Edison Model 0 introduced by the A.B. Dick Company in 1887, which featured a wooden frame with a tray for the stencil and required operators to manually roll ink across the surface using a brayer before pressing paper underneath. These hand-operated flatbeds limited output to operator speed and produced up to 600–1,000 copies per hour, suitable for small runs but labor-intensive.[2][22] Rotary mimeographs, emerging around 1900, represented a major advancement by wrapping the stencil around a rotating ink cylinder, allowing continuous operation via a hand crank that turned the drum while feeding paper between it and an impression roller. The A.B. Dick No. 75 rotary model, produced from approximately 1905 to 1930, exemplified this design, achieving 50–100 copies per minute and supporting up to 17,000–20,000 daily prints from durable stencils. Ink was loaded into the drum's reservoir, distributed evenly across a felt pad, and squeezed through stencil perforations as the cylinder rotated.[31][22] Subsequent models like the A.B. Dick No. 77 and No. 78, from the early 20th century, introduced refinements including optional automatic paper feeding in the No. 78 variant and compatibility with electric motors for speeds up to 100 RPM, far exceeding hand-cranked limits tied to operator endurance. Electric operation involved attaching a motor drive to the crankshaft, connecting to a 110-volt circuit, and adjusting pulleys for consistent rotation, enabling long runs without fatigue. Setup for these included aligning feedboards, filling the ink fountain to near capacity, and ensuring even ink spread with a fountain brush before commencing duplication. Hand-fed modes remained viable for short runs or specialty papers requiring precise registration.[32] Competitive variants, such as Gestetner rotary cyclostyle duplicators, operated on similar principles but emphasized patented wheel-point styluses for stencil cutting and achieved outputs of 1,200 copies per hour in early automatic models. These machines, produced from the late 19th century, featured adjustable carriages for stencil clamping and ink vents for controlled saturation, adapting the rotary drum for office and industrial use. Overall, machine variants evolved from rudimentary flatbeds to sophisticated rotary systems, prioritizing scalability while maintaining low-cost ink and stencil consumables.[33]Performance Attributes

Capacity and Durability

A single mimeograph stencil typically enabled the production of thousands of copies, depending on factors such as stencil material quality, ink viscosity, paper absorbency, and operational pressure, with output declining as perforations enlarged from repeated inking.[1] Higher-quality stencils, often coated with wax-impregnated tissue, sustained clearer reproductions longer by resisting abrasion, while coarser setups limited runs to fewer hundred copies before blurring occurred due to pore widening and ink buildup. Stencil durability was inherently finite, governed by mechanical stress from ink extrusion and paper friction, which causally eroded fine details over successive impressions; proper alignment and moderate speeds mitigated wear, but exhaustion necessitated replacement after the viable run. Machines exhibited robust construction, with rotary models featuring durable metal drums and gears that supported high-volume, repeated use across decades in institutional settings, though manual variants were prone to operator fatigue rather than mechanical failure. Produced copies showed moderate longevity on acid-free substrates, but overall print stability averaged around 10 years before yellowing or fading from acidic papers and light-sensitive inks compromised readability.[34]Advantages in Cost and Scalability

Mimeograph machines provided substantial cost savings compared to conventional printing techniques such as letterpress, which required skilled typesetting and plate-making. Early models, like those marketed by the A.B. Dick Company under Edison's patents, retailed for as little as $15 in the 1890s—equivalent to approximately $500 in present-day value—making them accessible to schools, offices, and small organizations. Stencils, typically made from waxed paper or fabric, cost fractions of a cent each, while ink and paper were inexpensive commodities, resulting in per-copy expenses often under one cent for medium runs.[3][5] The process's scalability stemmed from its ability to generate high volumes from a single prepared stencil, with capacities reaching up to 5,000 copies before significant wear, though practical limits were often several hundred for optimal quality. Machines operated at speeds of 45 to 50 copies per minute on rotary models, enabling rapid production without the setup delays of platemaking or the labor-intensive adjustments of letterpress. This efficiency scaled well for duplicating newsletters, bulletins, and forms in quantities unsuitable for professional presses but exceeding manual copying, democratizing information replication for budget-constrained users like educators and administrators.[35][5][36]