Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Moll Flanders

View on WikipediaThis article possibly contains original research. (April 2020) |

Moll Flanders[a] is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published in 1722. It purports to be the true account of the life of the eponymous Moll, detailing her exploits from birth until old age.

Key Information

By 1721, Defoe had become a recognised novelist, with the success of Robinson Crusoe in 1719. His political work was tapering off at this point, due to the fall of both Whig and Tory party leaders with whom he had been associated. Robert Walpole was beginning his rise, and Defoe was never fully at home with Walpole's group. Defoe's Whig views are evident in the story of Moll, and the novel's full title gives some insight into this and the outline of the plot.[1]

It is usually assumed that the novel was written by Daniel Defoe, and his name is commonly given as the author in modern printings of the novel. However, the original printing did not have an author, as it was an apparent autobiography.[2] The attribution of Moll Flanders to Defoe was made by bookseller Francis Noble in 1770, after Defoe's death in 1731.[3] The novel is based partially on the life of Moll King, a London criminal whom Defoe met while visiting Newgate Prison.

Historically, the book was occasionally the subject of police censorship.[4]

Plot

[edit]

Moll's mother is a convict in Newgate Prison in London who is given a reprieve by "pleading her belly," a reference to the custom of postponing the executions of pregnant criminals. Her mother is eventually transported to British America. Moll Flanders is raised from the age of three until adolescence by a kindly foster mother. Moll Flanders is not her birth name, she emphasises, taking care not to reveal it.

She gets attached to a household as a servant where she is loved by both sons, the elder of whom convinces her to "act like they were married" in bed. Unwilling to marry her, he persuades her to marry his younger brother. After five years of marriage, she then is widowed, leaves her children in the care of in-laws, and begins honing the skill of passing herself off as a fortuned widow to attract a man who will marry her and provide her with security.

The first time she does this, her "gentleman-tradesman" spendthrift husband goes bankrupt and flees to mainland Europe, leaving her on her own with his blessing to do the best she can to forget him. They had one child together, but "it was buried." The second time, she makes a match that leads her to Virginia Colony with a kindly man who introduces her to his mother.

After three children, with one dying, Moll learns that her mother-in-law is actually her biological mother, which makes her husband her half-brother. She dissolves their marriage and after continuing to live with her brother for three years, travels back to England, leaving her two children behind. Moll goes to live in Bath to seek a new husband.

Again she returns to her con skills and develops a relationship with a man in Bath, whose wife is elsewhere confined due to insanity. Their relationship is at first platonic, but eventually develops into Moll becoming something of a "kept woman" in Hammersmith, London. They have three children, with one surviving. After a severe illness Moll's partner repents, breaks off the arrangement, and commits to his wife. He assures Moll that their son will be well cared for, so she leaves yet another child behind.

Moll, now 42, resorts to another beau, a bank clerk, who while still married to an adulterous wife (a "whore"), proposes to Moll after she entrusts him with her financial holdings. While waiting for the banker to divorce, Moll pretends to have a great fortune to attract another wealthy husband in Lancashire, assisted by a new female acquaintance who attests to Moll's fictitious social standing. The ruse is successful, and she marries Jemmy, a supposedly rich man who claims to own property in Ireland.

They each quickly realise that they were both conned and manipulated by the acquaintance. He discharges her from the marriage, telling her that she should inherit any money he might ever get. After enjoying each other's company for about a month, they part ways, but Moll soon discovers that she is pregnant. She gives birth and the midwife gives a tripartite scale of the costs of bearing a child, with one value level per social class. She continues to correspond with the bank clerk, hoping he will still have her.

Moll leaves her newborn in the care of a countrywoman in exchange for the sum of £5 a year. Moll marries the banker, but realises "what an abominable creature I am! and how this innocent gentleman is going to be abused by me!". They live in happiness for five years before he becomes bankrupt and dies of despair, the fate of their two children left unstated.

Truly desperate now, Moll begins a career of artful thievery, which, by employing her wits, beauty, charm, and femininity, as well as hard-heartedness and wickedness, brings her the financial security she has always sought. She becomes well known among those "in the trade," and is given the name Moll Flanders. She is helped throughout her career as a thief by her Governess, who also acts as receiver. During this time she briefly becomes the mistress of a man she robbed. Moll is finally caught by two maids while trying to steal from a house.

In Newgate she is led to her repentance. At the same time, she reunites with her soulmate, her "Lancashire husband", who is also jailed for his robberies, before and after they first met, he acknowledges. Moll is found guilty of felony, but not burglary, the second charge. The sentence is death. Moll convinces a minister of her repentance, and together with her Lancashire husband is transported to the Colonies to avoid hanging, where they live happily together. She even talks the ship's captain into letting them stay in his quarters, apart from the other convicts, who are sold on arrival. Once in the colonies, Moll learns her mother has left her a plantation and that her own son, by her brother, is alive, as is her husband/brother.

Moll carefully introduces herself to her brother and their son, in disguise. With the help of a Quaker, the two found a farm with 50 servants in Maryland. Moll reveals herself now to her son in Virginia and he gives her her mother's inheritance, a farm for which he will now be her steward, providing £100 a year income for her. She makes him her heir, and gives him a stolen gold watch.

At last, her life of conniving and desperation seems to be over. After her husband/brother dies, Moll tells her Lancashire husband the entire story and he is "perfectly easy on that account... For, said he, it was no fault of yours, nor of his; it was a mistake impossible to be prevented." Aged 69 in 1683, the two return to England to live "in sincere penitence for the wicked lives we have lived."

Gender roles

[edit]According to Swaminathan (2003), Moll Flanders provides a window into women’s ways of being that do not reflect 18th century gender norms. Moll is reliant on alliances and friendships with women, many of whom fall outside of the gendered expectations of the era, she marries five times, and she has sexual relationships outside of marriage.[5]

One of Defoe’s notable contributions to 18th century ideas of female empowerment rests on the notion of women as agents of their own wealth. As Kuhlisch notes, “From the beginning, [Moll] does not believe that she is naturally poor but considers herself entitled to a more affluent life… [and she] defines her identity through her social position, which results from the material effects of her economic activities" (341).[6] That said, it may also be Defoe's “antipathy for England's commoners” that contributed to Moll's socioeconomic ascension (p. 99).[7]

Spiritual autobiography

[edit]One of the major themes within the book, and a popular area of scholarly research regarding its writer Daniel Defoe, is that of spiritual autobiography. Spiritual autobiography is defined as "a genre of non-fiction prose that dominated Protestant writing during the seventeenth century, particularly in England, particularly that of dissenters". Books within this genre follow a pattern of shallow repentances, followed by a fall back into sin, and eventually culminating in a conversion experience that has a profound impact on the course of their life from that point. The two scholars first to analyze the pattern of spiritual autobiography in Defoe's works, publishing within the same year, were George A. Starr and J. Paul Hunter.

George Starr's book, titled Defoe and Spiritual Autobiography, analyses the pattern of spiritual autobiography, and how it is found in Defoe's books. His focus in the book is primarily on Robinson Crusoe, as that is Defoe's book that follows the clearest pattern of spiritual autobiography. He discusses Moll Flanders at length, stating that the disconnectedness of the events in the book can be attributed to the book's spiritual autobiographical nature. He examines the pattern of spiritual autobiography in these events, with the beginning of her fall into sin being a direct results of her vanity prevailing over her virtue.[8]

Moll's "abortive repentances" are highlighted, such as her "repentance" after marrying the bank clerk. Moll is unable to break the pattern of sin that she falls into, one of habitual sin, in which one sin leads to another. Starr describes this gradual process as "hardening", and points to it as what makes up the basic pattern of her spiritual development. In examining her conversion experience, Starr highlights her motive as being "the reunion with her Lancashire husband, and the news that she is to be tried at the next Session, caused her 'wretched boldness of spirit' to abate. 'I began to think,’ she says, 'and to think indeed is one real advance from hell to heaven" (157).[9]

The culmination of her repentance comes the morning after this moment, when reflecting on the words of the minister that she confessed her sins to. Starr's main criticism of the book as a work of spiritual autobiography stems from the fact that only part, and not all, of Moll's actions contain spiritual significance. The overall pattern is consistent, but does not cover all sections, with some of those other sections focusing in more on social issues/social commentary.[10]

Film, television, or theatrical adaptations

[edit]- A 1965 film adaptation titled The Amorous Adventures of Moll Flanders starred Kim Novak as Moll Flanders and Richard Johnson as Jemmy with Angela Lansbury as Lady Blystone, with George Sanders as the banker, and Lilli Palmer as Dutchy. Some of the scenes were shot in Castle Lodge, a Tudor house in the centre of Ludlow, Shropshire, England.

- A 1975 two-part BBC TV adaptation, Moll Flanders, adapted by Hugh Whitemore, directed by Donald McWhinnie, and starring Julia Foster as Moll and Kenneth Haigh as Jemmy.

- In February 1982, an American musical adaptation titled MOLL!, with book by William SanGiacomo and music and lyrics by Thomas Young, received six performances by the Angola Community Theatre, Angola, Indiana.

- In 1993, A musical adaptation was recorded, starring Josie Lawrence as Moll Flanders, with Musical Direction by Tony Castro.

- In 1996, an American adaptation, Moll Flanders (1996), starred Robin Wright Penn as Moll Flanders and Morgan Freeman as Hibble, with Stockard Channing as Mrs. Allworthy. This adaptation shares only the title character, as most elements of the original novel are missing.

- In 1996, a second British television adaptation, broadcast by ITV, titled The Fortunes and Misfortunes of Moll Flanders, with Alex Kingston starring as Moll and Daniel Craig as Jemmy. This film is one of the closest adaptations to the novel, though it ends when she is still a relatively young woman.

- In 2016, a two-part radio adaptation by Nick Perry starring Jessica Hynes was broadcast on BBC Radio 4. In 2018, a musical version of Perry's adaptation was staged at the Mercury Theatre, Colchester.[11]

Notes

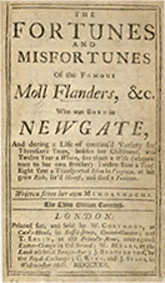

[edit]- ^ Full title: The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders, &c. Who was Born in Newgate, and during a Life of continu'd Variety for threescore Years, besides her Childhood, was Twelve Year a Whore, five times a Wife (whereof once to her own Brother) Twelve Year a Thief, Eight Year a Transported Felon in Virginia, at last grew Rich, liv'd Honest, and died a Penitent

References

[edit]- ^ Defoe, Daniel (1722). The fortunes and misfortunes of the famous Moll Flanders, &c. Who was born in Newgate, and during a Life of continu'd Variety for Threescore Years, besides her Childhood, was Twelve Year a Whore, five times a Wife (whereof once to her own Brother) Twelve Year a Thief, Eight Year a Transported Felon in Virginia, at last grew Rich, liv'd Honest, and died a Penitent, Written from her own memorandums. Eighteenth Century Collections Online: W. Chetwood.

- ^ "Title Page for 'Moll Flanders' by Daniel Defoe, published 1722". PBS LearningMedia. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- ^ Furbank and Owens "The Canonisation of Daniel Defoe" (1988); "Defoe De-Attributions" (1994) and "A Critical Bibliography of Daniel Defoe" (1998)

- ^ Peter Coleman, "Censorship: Publish and Be Damned." Media International Australia 150.1 (2014): 36–40.

- ^ Swaminathan, Srividhya (2003). "Defoe's Alternative Conduct Manual: Survival Strategies and Female Networks in Moll Flanders". Eighteenth-Century Fiction. 15 (2): 185–206. doi:10.1353/ecf.2003.0032. ISSN 1911-0243. S2CID 161716438.

- ^ Kuhlisch, Tina (2004). "The Ambivalent Rogue: Moll Flanders as Modern Pícara". Rogues and Early Modern English Culture. University of Michigan Press.

- ^ Melissa Mowry (2008). "Women, Work, Rearguard Politics, and Defoe's Moll Flanders". The Eighteenth Century. 49 (2): 97–116. doi:10.1353/ecy.0.0008. ISSN 1935-0201. S2CID 159678067.

- ^ Starr, George A. (1971). Defoe & spiritual autobiography. Gordian Press. ISBN 0877521387. OCLC 639738278.

- ^ Starr, George A. (1971). Defoe & spiritual autobiography. Gordian Press. ISBN 0877521387. OCLC 639738278.

- ^ Starr, George A. (1971). Defoe & spiritual autobiography. Gordian Press. ISBN 0877521387. OCLC 639738278.

- ^ "Moll Flanders". www.mercurytheatre.co.uk. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]Editions

[edit]- Defoe, Daniel. The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders ... Complete and Unabridged. (New York: The Modern Library (Subsidiary of Random House), (N.D., c. 1962–1964).

- Defoe, Daniel. Moll Flanders. (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2004). ISBN 978-0393978629. Edited with an introduction and notes by Albert J. Rivero. Contains a selection of essays and contextual material.

- Defoe, Daniel. Moll Flanders. (Wordsworth Classics, 2001). ISBN 978-1853260735. Edited with an introduction and notes by R. T. Jones.

Works of criticism

[edit]- Campbell, Ann. "Strictly Business: Marriage, Motherhood, and Surrogate Families as Entrepreneurial Ventures in Moll Flanders." Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 43.1 (2014): 51–68. online

- Chaber, Lois A. "Matriarchal Mirror: Women and Capital in Moll Flanders". PMLA, 97#2 1982.

- Gass, Joshua. "Moll Flanders and the Bastard Birth of Realist Character." New Literary History 45.1 (2014): 111–130. online

- Kibbie, Ann Louise. "Monstrous generation: the birth of capital in Defoe's Moll Flanders and Roxana." Publications of the Modern Language Association of America (1995): 1023–1034 online.

- Mowry, Melissa. "Women, work, rearguard politics, and Defoe's Moll Flanders." Eighteenth Century 49.2 (2008): 97–116. online

- Pollak, Ellen. "'Moll Flanders,' Incest, and the Structure of Exchange." The Eighteenth Century 30.1 (1989): 3–21. online

- Richetti, John Daniel Defoe (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987).

- Shinagel, Michael Daniel Defoe and Middle-Class Gentility (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968).

- Watt, Ian The Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding (London: Pimlico, 2000) ISBN 978-0712664271. Includes a chapter on Moll Flanders.

- Watt, Ian "The Recent Critical Fortunes of Moll Flanders". Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1967.