Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

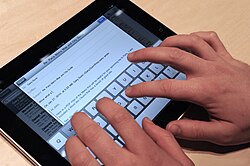

Multi-touch

View on Wikipedia

In computing, multi-touch is technology that enables a surface (a touchpad or touchscreen) to recognize the presence of more than one point of contact with the surface at the same time. The origins of multitouch began at CERN,[1] MIT, University of Toronto, Carnegie Mellon University and Bell Labs in the 1970s.[2] CERN started using multi-touch screens as early as 1976 for the controls of the Super Proton Synchrotron.[3][4] Capacitive multi-touch displays were popularized by Apple's iPhone in 2007.[5][6] Multi-touch may be used to implement additional functionality, such as pinch to zoom or to activate certain subroutines attached to predefined gestures using gesture recognition.

Several uses of the term multi-touch resulted from the quick developments in this field, and many companies using the term to market older technology which is called gesture-enhanced single-touch or several other terms by other companies and researchers. Several other similar or related terms attempt to differentiate between whether a device can exactly determine or only approximate the location of different points of contact to further differentiate between the various technological capabilities, but they are often used as synonyms in marketing.

Multi-touch is commonly implemented using capacitive sensing technology in mobile devices and smart devices. A capacitive touchscreen typically consists of a capacitive touch sensor, application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) controller and digital signal processor (DSP) fabricated from CMOS (complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor) technology. A more recent alternative approach is optical touch technology, based on image sensor technology.

Definition

[edit]In computing, multi-touch is technology which enables a touchpad or touchscreen to recognize more than one[7][8] or more than two[9] points of contact with the surface. Apple popularized the term "multi-touch" in 2007 with which it implemented additional functionality, such as pinch to zoom or to activate certain subroutines attached to predefined gestures.

The two different uses of the term resulted from the quick developments in this field, and many companies using the term to market older technology which is called gesture-enhanced single-touch or several other terms by other companies and researchers.[10][11] Several other similar or related terms attempt to differentiate between whether a device can exactly determine or only approximate the location of different points of contact to further differentiate between the various technological capabilities,[11] but they are often used as synonyms in marketing.

History

[edit]1960–2000

[edit]The use of touchscreen technology predates both multi-touch technology and the personal computer. Early synthesizer and electronic instrument builders like Hugh Le Caine and Robert Moog experimented with using touch-sensitive capacitance sensors to control the sounds made by their instruments.[12] IBM began building the first touch screens in the late 1960s. In 1972, Control Data released the PLATO IV computer, an infrared terminal used for educational purposes, which employed single-touch points in a 16×16 array user interface. These early touchscreens only registered one point of touch at a time. On-screen keyboards (a well-known feature today) were thus awkward to use, because key-rollover and holding down a shift key while typing another were not possible.[13]

Exceptions to these were a "cross-wire" multi-touch reconfigurable touchscreen keyboard/display developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the early 1970s [14] and the 16 button capacitive multi-touch screen developed at CERN in 1972 for the controls of the Super Proton Synchrotron that were under construction.[15]

In 1976 a new x-y capacitive screen, based on the capacitance touch screens developed in 1972 by Danish electronics engineer Bent Stumpe, was developed at CERN.[1][17] This technology, allowing an exact location of the different touch points, was used to develop a new type of human machine interface (HMI) for the control room of the Super Proton Synchrotron particle accelerator.[18][19][20] In a handwritten note dated 11 March 1972,[21] Stumpe presented his proposed solution – a capacitive touch screen with a fixed number of programmable buttons presented on a display. The screen was to consist of a set of capacitors etched into a film of copper on a sheet of glass, each capacitor being constructed so that a nearby flat conductor, such as the surface of a finger, would increase the capacitance by a significant amount. The capacitors were to consist of fine lines etched in copper on a sheet of glass – fine enough (80 μm) and sufficiently far apart (80 μm) to be invisible.[22] In the final device, a simple lacquer coating prevented the fingers from actually touching the capacitors. In the same year, MIT described a keyboard with variable graphics capable of multi-touch detection.[14]

In the early 1980s, The University of Toronto's Input Research Group were among the earliest to explore the software side of multi-touch input systems.[23] A 1982 system at the University of Toronto used a frosted-glass panel with a camera placed behind the glass. When a finger or several fingers pressed on the glass, the camera would detect the action as one or more black spots on an otherwise white background, allowing it to be registered as an input. Since the size of a dot was dependent on pressure (how hard the person was pressing on the glass), the system was somewhat pressure-sensitive as well.[12] Of note, this system was input only and not able to display graphics.

In 1983, Bell Labs at Murray Hill published a comprehensive discussion of touch-screen based interfaces, though it makes no mention of multiple fingers.[24] In the same year, the video-based Video Place/Video Desk system of Myron Krueger was influential in development of multi-touch gestures such as pinch-to-zoom, though this system had no touch interaction itself.[25][26]

By 1984, both Bell Labs and Carnegie Mellon University had working multi-touch-screen prototypes – both input and graphics – that could respond interactively in response to multiple finger inputs.[27][28] The Bell Labs system was based on capacitive coupling of fingers, whereas the CMU system was optical. In 1985, the canonical multitouch pinch-to-zoom gesture was demonstrated, with coordinated graphics, on CMU's system.[29][30] In October 1985, Steve Jobs signed a non-disclosure agreement to tour CMU's Sensor Frame multi-touch lab.[31] In 1990, Sears et al. published a review of academic research on single and multi-touch touchscreen human–computer interaction of the time, describing single touch gestures such as rotating knobs, swiping the screen to activate a switch (or a U-shaped gesture for a toggle switch), and touchscreen keyboards (including a study that showed that users could type at 25 words per minute for a touchscreen keyboard compared with 58 words per minute for a standard keyboard, with multi-touch hypothesized to improve data entry rate); multi-touch gestures such as selecting a range of a line, connecting objects, and a "tap-click" gesture to select while maintaining location with another finger are also described.[32]

In 1991, Pierre Wellner advanced the topic publishing about his multi-touch "Digital Desk", which supported multi-finger and pinching motions.[33][34] Various companies expanded upon these inventions in the beginning of the twenty-first century.

2000–present

[edit]Between 1999 and 2005, the company Fingerworks developed various multi-touch technologies, including Touchstream keyboards and the iGesture Pad. in the early 2000s Alan Hedge, professor of human factors and ergonomics at Cornell University published several studies about this technology.[35][36][37] In 2005, Apple acquired Fingerworks and its multi-touch technology.[38]

In 2004, French start-up JazzMutant developed the Lemur Input Device, a music controller that became in 2005 the first commercial product to feature a proprietary transparent multi-touch screen, allowing direct, ten-finger manipulation on the display.[39][40]

In January 2007, multi-touch technology became mainstream with the iPhone, and in its iPhone announcement Apple even stated it "invented multi touch",[41] however both the function and the term predate the announcement or patent requests, except for the area of capacitive mobile screens, which did not exist before Fingerworks/Apple's technology (Fingerworks filed patents in 2001–2005,[42] subsequent multi-touch refinements were patented by Apple[43]).

However, the U.S. Patent and Trademark office declared that the "pinch-to-zoom" functionality was predicted by U.S. Patent # 7,844,915[44][45] relating to gestures on touch screens, filed by Bran Ferren and Daniel Hillis in 2005, as was inertial scrolling,[46] thus invalidated a key claims of Apple's patent.

In 2001, Microsoft's table-top touch platform, Microsoft PixelSense (formerly Surface) started development, which interacts with both the user's touch and their electronic devices and became commercial on May 29, 2007. Similarly, in 2001, Mitsubishi Electric Research Laboratories (MERL) began development of a multi-touch, multi-user system called DiamondTouch.

In 2008, the Diamondtouch became a commercial product and is also based on capacitance, but able to differentiate between multiple simultaneous users or rather, the chairs in which each user is seated or the floorpad on which the user is standing. In 2007, NORTD labs open source system offered its CUBIT (multi-touch).

Small-scale touch devices rapidly became commonplace in 2008. The number of touch screen telephones was expected to increase from 200,000 shipped in 2006 to 21 million in 2012.[47]

In May 2015, Apple was granted a patent for a "fusion keyboard", which turns individual physical keys into multi-touch buttons.[48]

Applications

[edit]

Apple has retailed and distributed numerous products using multi-touch technology, most prominently including its iPhone smartphone and iPad tablet. Additionally, Apple also holds several patents related to the implementation of multi-touch in user interfaces,[49] however the legitimacy of some patents has been disputed.[50] Apple additionally attempted to register "Multi-touch" as a trademark in the United States—however its request was denied by the United States Patent and Trademark Office because it considered the term generic.[51]

Multi-touch sensing and processing occurs via an ASIC sensor that is attached to the touch surface. Usually, separate companies make the ASIC and screen that combine into a touch screen; conversely, a touchpad's surface and ASIC are usually manufactured by the same company. There have been large companies in recent years that have expanded into the growing multi-touch industry, with systems designed for everything from the casual user to multinational organizations.

It is now common for laptop manufacturers to include multi-touch touchpads on their laptops, and tablet computers respond to touch input rather than traditional stylus input and it is supported by many recent operating systems.

A few companies are focusing on large-scale surface computing rather than personal electronics, either large multi-touch tables or wall surfaces. These systems are generally used by government organizations, museums, and companies as a means of information or exhibit display.[citation needed]

Implementations

[edit]Multi-touch has been implemented in several different ways, depending on the size and type of interface. The most popular form are mobile devices, tablets, touchtables and walls. Both touchtables and touch walls project an image through acrylic or glass, and then back-light the image with LEDs.

Touch surfaces can also be made pressure-sensitive by the addition of a pressure-sensitive coating that flexes differently depending on how firmly it is pressed, altering the reflection.[52]

Handheld technologies use a panel that carries an electrical charge. When a finger touches the screen, the touch disrupts the panel's electrical field. The disruption is registered as a computer event (gesture) and may be sent to the software, which may then initiate a response to the gesture event.[53]

In the past few years, several companies have released products that use multi-touch. In an attempt to make the expensive technology more accessible, hobbyists have also published methods of constructing DIY touchscreens.[54]

Capacitive

[edit]Capacitive technologies include:[55]

- Surface Capacitive Technology or Near Field Imaging (NFI)

- Projected Capacitive Touch (PCT)

- In-cell Capacitive

Resistive

[edit]Resistive technologies include:[55]

- Analog Resistive

- Digital Resistive or In-Cell Resistive

Optical

[edit]Optical touch technology is based on image sensor technology. It functions when a finger or an object touches the surface, causing the light to scatter, the reflection of which is caught with sensors or cameras that send the data to software that dictates response to the touch, depending on the type of reflection measured.

Optical technologies include:[55]

- Optical Imaging or Infrared technology

- Rear Diffused Illumination (DI)[56]

- Infrared Grid Technology (opto-matrix) or Digital Waveguide Touch (DWT) or Infrared Optical Waveguide

- Frustrated Total Internal Reflection (FTIR)

- Diffused Surface Illumination (DSI)

- Laser Light Plane (LLP)

- In-Cell Optical

Wave

[edit]Acoustic and radio-frequency wave-based technologies include:[55]

- Surface Acoustic Wave (SAW)

- Bending Wave Touch (BWT)

- Dispersive Signal Touch (DST)

- Acoustic Pulse Recognition (APR)

- Force-Sensing Touch Technology

Multi-touch gestures

[edit]Multi-touch touchscreen gestures enable predefined motions to interact with the device and software. An increasing number of devices like smartphones, tablet computers, laptops or desktop computers have functions that are triggered by multi-touch gestures.

Popular culture

[edit]Before 2007

[edit]Years before it was a viable consumer product, popular culture portrayed potential uses of multi-touch technology in the future, including in several installments of the Star Trek franchise.

In the 1982 Disney sci-fi film Tron a device similar to the Microsoft Surface was shown. It took up an executive's entire desk and was used to communicate with the Master Control computer.

In the 2002 film Minority Report, Tom Cruise uses a set of gloves that resemble a multi-touch interface to browse through information.[57]

In the 2005 film The Island, another form of a multi-touch computer was seen where the professor, played by Sean Bean, has a multi-touch desktop to organize files, based on an early version of Microsoft Surface[2] (not be confused with the tablet computers which now bear that name).

In 2007, the television series CSI: Miami introduced both surface and wall multi-touch displays in its sixth season.

After 2007

[edit]Multi-touch technology can be seen in the 2008 James Bond film Quantum of Solace, where MI6 uses a touch interface to browse information about the criminal Dominic Greene.[58]

In the 2008 film The Day the Earth Stood Still, Microsoft's Surface was used.[59]

The television series NCIS: Los Angeles, which premiered 2009, makes use of multi-touch surfaces and wall panels as an initiative to go digital.

In a 2008, an episode of the television series The Simpsons, Lisa Simpson travels to the underwater headquarters of Mapple to visit Steve Mobbs, who is shown to be performing multiple multi-touch hand gestures on a large touch wall.

In the 2009, the film District 9 the interface used to control the alien ship features similar technology.[60]

10/GUI

[edit]10/GUI is a proposed new user interface paradigm. Created in 2009 by R. Clayton Miller, it combines multi-touch input with a new windowing manager.

It splits the touch surface away from the screen, so that user fatigue is reduced and the users' hands don't obstruct the display.[61] Instead of placing windows all over the screen, the windowing manager, Con10uum, uses a linear paradigm, with multi-touch used to navigate between and arrange the windows.[62] An area at the right side of the touch screen brings up a global context menu, and a similar strip at the left side brings up application-specific menus.

An open source community preview of the Con10uum window manager was made available in November, 2009.[63]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Stumpe, Bent (16 March 1977), A new principle for x-y touch system (PDF), CERN, retrieved 2010-05-25

- ^ "Multi-Touch Technology and the Museum: An Introduction". AMT Lab @ CMU. 18 October 2015. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- ^ Crowley-Milling, Michael (29 September 1977). New Scientist. Reed Business Information. pp. 790–791.

- ^ Doble, Niels; Gatignon, Lau; Hübner, Kurt; Wilson, Edmund (2017-04-24). "The Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS): A Tale of Two Lives". Advanced Series on Directions in High Energy Physics. World Scientific. pp. 152–154. doi:10.1142/9789814749145_0005. ISBN 978-981-4749-13-8. ISSN 1793-1339.

- ^ Kent, Joel (May 2010). "Touchscreen technology basics & a new development". CMOS Emerging Technologies Conference. 6. CMOS Emerging Technologies Research: 1–13. ISBN 9781927500057.

- ^ Ganapati, Priya (5 March 2010). "Finger Fail: Why Most Touchscreens Miss the Point". Wired. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Multi-touch definition of Multi-touch in the Free Online Encyclopedia". encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com. Retrieved 2014-11-23.

- ^ "Glossary - X2 Computing". x2computing.com. Archived from the original on 2014-08-17. Retrieved 2014-11-23.

- ^ Gardner, N.; Haeusler, H.; Tomitsch, M. (2010). Infostructures: A Transport Research Project. Freerange Press. ISBN 9780980868906. Retrieved 2014-11-23.

- ^ Walker, Geoff (August 2012). "A review of technologies for sensing contact location on the surface of a display". Journal of the Society for Information Display. 20 (8): 413–440. doi:10.1002/jsid.100. S2CID 40545665.

- ^ a b "What is Multitouch". Retrieved 2010-05-30.

- ^ a b Buxton, Bill. "Multitouch Overview"

- ^ "Multi-Touch Technology, Applications and Global Markets". www.prnewswire.com (Press release). Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ^ a b Kaplow, Roy; Molnar, Michael (1976-01-01). "A computer-terminal, hardware/Software system with enhanced user input capabilities: The enhanced-input terminal system (EITS)". Proceedings of the 3rd annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques - SIGGRAPH '76. pp. 116–124. doi:10.1145/563274.563297. S2CID 16749393.

- ^ Beck, Frank; Stumpe, Bent (May 24, 1973). Two devices for operator interaction in the central control of the new CERN accelerator (Report). CERN. doi:10.5170/CERN-1973-006. CERN-73-06. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- ^ The first capacitative touch screens at CERN, CERN Courrier, 31 March 2010, retrieved 2010-05-25

- ^ Stumpe, Bent (6 February 1978), Experiments to find a manufacturing process for an x-y touch screen (PDF), CERN, retrieved 2010-05-25

- ^ Petersen, Peter (1983). Man-machine communication (Bachelor). Aalborg University.

- ^ Merchant, Brian (22 June 2017). The One Device: The Secret History of the iPhone. Transworld. ISBN 978-1-4735-4254-9.

- ^ Henriksen, Benjamin; Munch Christensen, Jesper; Stumpe, Jonas (2012). The evolution of CERN's capacitive touchscreen (PDF) (Bachelor). University of Copenhagen.

- ^ Stumpe, Bent; Sutton, Christine (1 June 2010). "CERN touch screen". Symmetry Magazine. A joint Fermilab/SLAC publication. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ "Data processing". CERN Courier. 14 (4): 116–17. 1974.

- ^ Mehta, Nimish (1982), A Flexible Machine Interface, M.A.Sc. Thesis, Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Toronto supervised by Professor K.C. Smith.

- ^ Nakatani, L. H., John A Rohrlich; Rohrlich, John A. (1983). "Soft machines". Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI '83. pp. 12–15. doi:10.1145/800045.801573. ISBN 978-0897911214. S2CID 12140440.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krueger, Myron (7 April 2008). "Videoplace '88". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-14.

- ^ Krueger, Myron, W., Gionfriddo, Thomas., &Hinrichsen, Katrin (1985). VIDEOPLACE - An Artificial Reality, Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI’85), 35–40.

- ^ Dannenberg, R.B., McAvinney, P. and Thomas, M.T. Carnegie-Mellon University Studio Report. In Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference (Paris, France, October 19–23, 1984). ICMI. pp. 281-286.

- ^ McAvinney, P. The Sensor Frame - A Gesture-Based Device for the Manipulation of Graphic Objects. Carnegie Mellon University, 1986.

- ^ TEDx Talks (2014-06-15), Future of human/computer interface: Paul McAvinney at TEDxGreenville 2014, archived from the original on 2021-12-14, retrieved 2017-02-24

- ^ Lee, SK; Buxton, William; Smith, K. C. (1985-01-01). "A multi-touch three dimensional touch-sensitive tablet". Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems - CHI '85. New York: ACM. pp. 21–25. doi:10.1145/317456.317461. ISBN 978-0897911498. S2CID 1196331.

- ^ O'Connell, Kevin. "The Untold History of MultiTouch" (PDF). pp. 14–17. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- ^ Sears, A., Plaisant, C., Shneiderman, B. (June 1990) A new era for high-precision touchscreens. Advances in Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 3, Hartson, R. & Hix, D. Eds., Ablex (1992) 1-33 HCIL-90-01, CS-TR-2487, CAR-TR-506. [1]

- ^ Wellner, Pierre. 1991. The Digital Desk. Video on YouTube

- ^ Pierre Wellner's papers Archived 2012-07-18 at the Wayback Machine via DBLP

- ^ Westerman, W., Elias J.G. and A.Hedge (2001) Multi-touch: a new tactile 2-d gesture interface for human-computer interaction Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 45th Annual Meeting, Vol. 1, 632-636.

- ^ Shanis, J. and Hedge, A. (2003) Comparison of mouse, touchpad and multitouch input technologies. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 47th Annual Meeting, Oct. 13–17, Denver, CO, 746-750.

- ^ Thom-Santelli, J. and Hedge, A. (2005) Effects of a multitouch keyboard on wrist posture, typing performance and comfort. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 49th Annual Meeting, Orlando, Sept. 26-30, HFES, Santa Monica, 646-650.

- ^ Heisler, Yoni (June 25, 2013). "Apple's most important acquisitions". Network World.

- ^ Buxton, Bill. "Multi-Touch Systems that I Have Known and Loved". billbuxton.com/.

- ^ Guillaume, Largillier. "Developing the First Commercial Product that Uses Multi-Touch Technology". informationdisplay.org/. SID Information Display Magazine. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ Steve Jobs (2006). "And Boy Have We Patented It". Retrieved 2010-05-14.

And we have invented a new technology called Multi-touch

- ^ "US patent 7,046,230 "Touch pad handheld device"".

- ^ Jobs; et al. "Touch Screen Device, Method, and Graphical User Interface for Determining Commands by Applying Heuristics". Archived from the original on 2005-07-20. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ^ US 7844915, Platzer, Andrew & Herz, Scott, "Application programming interfaces for scrolling operations", published 2010-11-30

- ^ "US patent office rejects claims of Apple 'pinch to zoom' patent". PCWorld. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ^ US 7724242, Hillis, W. Daniel & Ferren, Bran, "Touch driven method and apparatus to integrate and display multiple image layers forming alternate depictions of same subject matter", published May 25, 2010

- ^ Wong, May. 2008. Touch-screen phones poised for growth https://www.usatoday.com/tech/products/2007-06-21-1895245927_x.htm. Retrieved April 2008.

- ^ "Apple Patent Tips Multi-Touch Keyboard". 26 May 2015.

- ^ Heater, Brian (27 January 2009). "Key Apple Multi-Touch Patent Tech Approved". PCmag.com. Retrieved 2011-09-27.

- ^ "Apple's Pinch to Zoom Patent Has Been Tentatively Invalidated". Gizmodo. 20 December 2012. Retrieved 2013-06-12.

- ^ Golson, Jordan (26 September 2011). "Apple Denied Trademark for Multi-Touch". MacRumors. Retrieved 2011-09-27.

- ^ Scientific American. 2008. "How It Works: Multitouch Surfaces Explained". Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ Brandon, John. 2009. "How the iPhone Works Archived 2012-10-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ DIY Multi-touch screen

- ^ a b c d Knowledge base:Multitouch technologies. Digest author: Gennadi Blindmann

- ^ "Diffused Illumination (DI) - NUI Group". wiki.nuigroup.com. Archived from the original on 2008-10-16.

- ^ Minority Report Touch Interface for Real. Gizmodo.com. Retrieved on 2013-12-09.

- ^ 2009. " Quantum of Solace Multitouch UI"

- ^ Garofalo, Frank Joseph. "User Interfaces For Simultaneous Group Collaboration Through Multi-Touch Devices". Purdue University. p. 17. Retrieved 2012-06-03.

- ^ "District 9 - Ship UI" on YouTube

- ^ Quick, Darren (October 14, 2009). "10/GUI the human computer interface of the future for people with more than two fingers". Gizmag.com. Retrieved 2009-10-14.

- ^ Melanson, Donald (October 15, 2009). "10/GUI interface looks to redefine the touch-enabled desktop". Engadget. Archived from the original on 19 October 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ Miller, R. Clayton (November 26, 2009). "WPF Con10uum: 10/GUI Software part". CodePlex. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

External links

[edit]- Multi-Touch Systems that I Have Known and Loved – An overview by researcher Bill Buxton of Microsoft Research, formerly at University of Toronto and Xerox PARC.

- The Unknown History of Pen Computing contains a history of pen computing, including touch and gesture technology, from approximately 1917 to 1992.

- Annotated bibliography of references to pen computing

- Annotated bibliography of references to tablet and touch computers

- Video: Notes on the History of Pen-based Computing on YouTube

- Multi-Touch Interaction Research @ NYU

- Camera-based multi-touch for wall-sized displays

- David Wessel Multitouch

- Jeff Han's Multi Touch Screen's chronology archive De

- Force-Sensing, Multi-Touch, User Interaction Technology Archived 2013-01-22 at the Wayback Machine

- LCD In-Cell Touch by Geoff Walker and Mark Fihn Archived 2017-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Touch technologies for large-format applications by Geoff Walker Archived 2017-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Video: Surface Acoustic Wave Touch Screens on YouTube

- Video: How 3M™ Dispersive Signal Technology Works on YouTube

- Video: Introduction to mTouch Capacitive Touch Sensing on YouTube