Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Multiple-document interface

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (August 2024) |

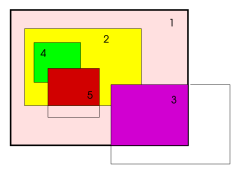

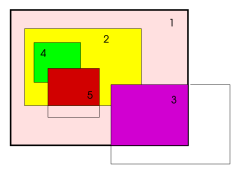

A multiple-document interface (MDI) is a graphical user interface in which multiple windows reside under a single parent window. Such systems often allow child windows to embed other windows inside them as well, creating complex nested hierarchies. This contrasts with single-document interfaces (SDI) where all windows are independent of each other.

Comparison with single-document interface

[edit]In the usability community, there has been much debate about whether the multiple-document or single-document interface is preferable. Software companies have used both interfaces with mixed responses. For example, Microsoft changed its Office applications from SDI to MDI mode and then back to SDI, although the degree of implementation varies from one component to another. SDI can be more useful in cases where users switch more often between separate applications than among the windows of one application.

MDI can be confusing if it has a lack of information about the currently opened windows. In MDI applications, the application developer must provide a way to switch between documents or view a list of open windows, and the user might have to use an application-specific menu ("window list" or something similar) to switch between open documents. This is different from SDI applications where the window manager's task bar or task manager displays the currently opened windows. In recent years it has become increasingly common for MDI applications to use "tabs" to display the currently opened windows. An interface in which tabs are used to manage open documents is referred to as a "tabbed document interface" (TDI). Another option is "tiled" panes or windows, which make it easier to prevent content from overlapping.

Some applications allow the user to switch between these modes at their choosing, depending on personal preference or the task at hand.

Nearly all graphical user interface toolkits to date provide at least one solution for designing MDIs. A notable exception was Apple's Cocoa API until the advent of tabbed window groups in MacOS High Sierra. The Java GUI toolkit, Swing, for instance, provides the class javax.swing.JDesktopPane which serves as a container for individual frames (class javax.swing.JInternalFrame). GTK lacks any standardized support for MDI.

Advantages

[edit]- With multiple-document interfaces (and also tabbed document interfaces), a single menu bar and/or toolbar is shared between all child windows, reducing clutter and increasing efficient use of screen space. This argument is less relevant on an operating system which uses a common menu bar.

- An application's child windows can be hidden/shown/minimized/maximized as a whole.

- Features such as "Tile" and "Cascade" can be implemented for the child windows.

- Authors of cross-platform applications can provide their users with consistent application behaviour between platforms.

- If the windowing environment and OS lack good window management, the application author can implement it themselves.

- Modularity: An advanced window manager can be upgraded independently of the applications.

Disadvantages

[edit]- Without an MDI frame window, floating toolbars from one application can clutter the workspace of other applications, potentially confusing users with the jumble of interfaces.

- Can be tricky to implement on desktops using multiple monitors as the parent window may need to span two or more monitors, hiding sections.

- Virtual desktops cannot be spanned by children of the MDI. However, in some cases, this is solvable by initiating another parent window; this is the case in Opera and Chrome, for example, which allows tabs/child windows to be dragged outside of the parent window to start their own parent window. In other cases, each child window is also a parent window, forming a new, "virtual" MDI [1].

- MDI can make it more difficult to work with several applications at once, by restricting the ways in which windows from multiple applications can be arranged together without obscuring each other.

- The shared menu might change, which may cause confusion to some users.

- MDI child windows behave differently from those in single-document interface applications, requiring users to learn two subtly different windowing concepts. Similarly, the MDI parent window behaves like the desktop in many respects, but has enough differences to confuse some users.

- Deeply nested, branching hierarchies of child windows can be confusing.

- Many window managers have built-in support for manipulating groups of separate windows, which is typically more flexible than MDI in that windows can be grouped and ungrouped arbitrarily. A typical policy is to group automatically windows that belong to the same application. This arguably makes MDI redundant by providing a solution to the same problem.

- Controls and hotkeys learned for the MDI application may not apply to others, whereas with an advanced Window Manager, more behavior and user preference settings are shared across client applications on the same system

Application examples

[edit]- Adobe Acrobat: MDI until version 7.0 (Windows-only); SDI default in 8.0 (configurable to MDI); SDI only in 9.0; MDI (with a tabbed interface) in version 2015.

- Corel Wordperfect: MDI. A user can open multiple instances of WP with a single document in each, if they have multiple versions of WordPerfect installed on their computer. Recent versions maintain a list of open documents for a given window on the status bar at the bottom of the window, providing a variant of the TDI.

- EmEditor: Options for either SDI or MDI.

- GIMP: SDI with floating windows (MDI is available as an option called "Single-Window Mode" since version 2.8 [2]).

- GIMPshop: A fork of GIMP aiming to be more like Adobe Photoshop. The Windows version has limited MDI.[3]

- Chrome: Combination of MDI and TDI.

- Internet Explorer 6: a typical SDI application

- KWrite: Another text editor designed for the KDE Software Compilation, with a simplified SDI but sharing many of Kate's features via a mutual back end

- Kate: Text editor designed for the KDE Software Compilation, with advanced features and a sophisticated MDI

- Macromedia Studio for Windows: a hybrid interface; TDI unless document windows are un-maximized. (They are maximized by default.)

- Microsoft Excel 2003: SDI if you start new instances of the application, but MDI if you click the "File → New" menu (but child windows optionally appear on the OS taskbar). SDI only as of 2013.

- Microsoft Word 2003: MDI until Microsoft Office 97. After 2000, Word has a Multiple Top-Level Windows Interface, thus exposing to shell individual SDI instances, while the operating system recognizes it as a single instance of an MDI application. In Word 2000, this was the only interface available, but 2002 and later offer MDI as an option. Microsoft Foundation Classes (which Office is loosely based on) supports this metaphor since version 7.0, as a new feature in Visual Studio 2002. SDI only as of 2013.

- Firefox: TDI by default, can be SDI

- Notepad++, PSPad, TextMate and many other text editors: TDI

- Opera: Combination of MDI and TDI (a true MDI interface with a tab bar for quick access).

- Paint.NET: Thumbnail-based, TDI

- UltraEdit: Combination of MDI and TDI (a true MDI interface with a tab bar for quick access).

- VEDIT: Combination of MDI and TDI (a true MDI interface with a tab bar for quick access). Special "Full size" windows act like maximized windows, but allow smaller overlapping windows to be used at the same time. Multiple instances of Vedit can be started, which allows it to be used like an SDI application.

- Visual Studio .NET: MDI or TDI with "Window" menu, but not both

- Visual Studio 6 development environment: a typical modern MDI

- mIRC: MDI by default, can also work on SDI mode

- Adobe Photoshop: MDI under Windows. In newer versions, toolbars can move outside the frame window. Child windows can be outside the frame unless they are minimized or maximized.

IDE-style interface

[edit]Graphical computer applications with an IDE-style interface (IDE) are those whose child windows reside under a single parent window (usually with the exception of modal windows). An IDE-style interface is distinguishable from the Multiple-Document Interface (MDI), because all child windows in an IDE-style interface are enhanced with added functionality not ordinarily available in MDI applications. Because of this, IDE-style applications can be considered a functional superset and descendant of MDI applications.

Examples of enhanced child-window functionality include:

- Dockable child windows

- Collapsible child windows

- Tabbed document interface for sub-panes

- Independent sub-panes of the parent window

- GUI splitters to resize sub-panes of the parent window

- Persistence for window arrangements

Collapsible child windows

[edit]A common convention for child windows in IDE-style applications is the ability to collapse child windows, either when inactive, or when specified by the user. Child windows that are collapsed will conform to one of the four outer boundaries of the parent window, with some kind of label or indicator that allows them to be expanded again.

Tabbed document interface for sub-panes

[edit]In contrast to (MDI) applications, which ordinarily allow a single tabbed interface for the parent window, applications with an IDE-style interface allow tabs for organizing one or more subpanes of the parent window.

IDE-style application examples

[edit]- NetBeans

- dBASE

- Eclipse

- Visual Studio 6

- Visual Studio .NET

- Visual Studio Code

- RSS Bandit

- JEdit

- MATLAB

- Microsoft Excel when in MDI mode (see above)

Macintosh

[edit]MacOS and its GUI are document-centric instead of window-centric or application-centric. Every document window is an object with which the user can work. The menu bar changes to reflect whatever application the front window belongs to. Application windows can be hidden and manipulated as a group, and the user may switch between applications (i.e., groups of windows) or between individual windows, automatically hiding palettes, and most programs will stay running even with no open windows. Indeed, prior to Mac OS X, it was purposely impossible to interleave windows from multiple applications.

In spite of this, some unusual applications breaking the human interface guidelines (most notably Photoshop) do exhibit different behavior.

See also

[edit]- Graphical user interface

- Comparison of document interfaces

- Tabbed document interface

- Tiling window manager

- Integrated development environment

- Center stage (user interface) - a user interface pattern used with single-document or IDE-style interfaces

References

[edit]- Human Computer Interaction. Laxmi Publications. 2005. ISBN 978-81-7008-795-3. Retrieved 2022-07-18.

External links

[edit]- Interface Hall of Shame arguments against MDI

- MDI forms using C# MDI forms in .net using C# and Visual Studio 2010 Express

Multiple-document interface

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

A multiple-document interface (MDI) is a graphical user interface (GUI) paradigm in which multiple child windows, each representing a separate document, are contained and managed within a single parent window of an application.[3][2] This design allows users to handle several related documents simultaneously in a unified space, facilitating efficient organization and access without requiring independent top-level windows for each file.[1] The primary components of an MDI include the parent frame window, which serves as the main container featuring elements such as a menu bar, toolbar, title bar, and control buttons for minimizing or maximizing the entire application.[3] Within this frame lies the MDI client window, which acts as the background area where child windows are hosted and managed.[3] Child windows, each dedicated to a specific document, are resizable, movable within the client area, and support standard operations like tiling (arranging non-overlapping for full visibility), cascading (stacking with exposed title bars), minimizing to icons within the parent, and maximizing to fill the client space.[3] Child windows in an MDI inherit key properties from the parent frame, including shared menus and toolbars that provide global commands applicable across documents, while allowing individual child-specific menu items to dynamically update the window menu (typically listing up to nine active children before using a "More Windows" submenu).[3] This inheritance ensures consistent application-wide behavior, such as unified scrolling controls and activation states managed by the client window, promoting a cohesive environment for multitasking on related documents without cluttering the underlying desktop.[2] In contrast, a single-document interface (SDI) employs independent top-level windows for each document, lacking this contained hierarchy.[2]Historical Development

The multiple-document interface (MDI) emerged in the 1980s as part of the broader evolution of graphical user interfaces (GUIs), building on foundational windowing concepts pioneered at Xerox PARC in the 1970s, such as overlapping windows in the Alto system that enabled multitasking through visual document management. Early GUI systems like Digital Research's GEM (1983-1985) featured multi-window management that influenced MDI concepts. These early ideas influenced commercial GUIs, but MDI as a structured paradigm was formalized and introduced by Microsoft in Windows 3.0, released on May 22, 1990, where the specification allowed multiple child windows within a parent frame to handle documents efficiently.[6][7][8] MDI gained prominence with the release of Windows 3.0 on May 22, 1990, which popularized the interface for productivity software by integrating it into the operating environment's core. Adoption accelerated in the Microsoft Office suite, with applications such as Word for Windows 2.0 (released in 1991) implementing MDI to support simultaneous document editing, aligning with the growing need for multitasking in desktop publishing during the PC boom. In the 1990s, toolkits like the Microsoft Foundation Classes (MFC), introduced in 1992 with Visual C++ 1.0, simplified MDI development by providing reusable classes for frame, client, and child windows, facilitating its widespread use in Windows applications.[8][9][10] Standardization of MDI occurred through key GUI frameworks in the 1990s and 2000s, including the Win32 API introduced with Windows NT 3.1 (1993) and Windows 95 (1995), which extended MDI support for 32-bit applications while maintaining backward compatibility. Cross-platform libraries followed, with Qt providing MDI capabilities via QWorkspace starting in Qt 3.0 (2001) and later QMdiArea in Qt 4.3 (2007), enabling developers to build MDI apps for Unix-like systems and Windows. GTK+, evolving from the 1990s, incorporated tabbed interfaces through widgets like GtkNotebook in GTK+ 2.0 (2002), but does not provide native support for traditional MDI and emphasizes single-document or tabbed designs. By the 2010s, MDI evolved into hybrid forms combining traditional child windows with tabbed interfaces, as seen in modern IDEs like Visual Studio, which uses tabbed MDI for code editing and tool windows.[3][11][12][13] MDI's development mirrored the cultural shift from command-line interfaces to graphical multitasking in desktop computing, particularly during the 1980s and 1990s PC boom, when hardware advances like affordable color displays and mice made visual paradigms essential for non-technical users handling multiple files in emerging office environments. This transition, driven by systems like Windows 3.0's success in selling millions of copies, underscored MDI's role in democratizing productivity tools amid the rise of personal computing.[6]Comparison with Single-Document Interface

Advantages of MDI

The multiple-document interface (MDI) provides a unified workspace by containing all child windows within a single parent window, which reduces desktop clutter and allows users to focus on related tasks without scattering multiple top-level windows across the screen.[3][14] This design facilitates easier switching between documents via built-in menu commands, such as those for tiling or cascading child windows, enabling simultaneous visibility of multiple documents in a coordinated space.[15][11] MDI supports shared resources across child windows, including a common menu bar, toolbar, and status bar, which minimizes redundancy and ensures consistent access to application controls regardless of the active document.[3] This shared structure streamlines user interactions by maintaining a single set of interface elements for the entire application, avoiding the need to duplicate menus or tools in each window.[15] In terms of resource efficiency, MDI incurs lower overhead in memory and system resources compared to opening multiple independent windows, as all documents operate within a single application instance and result in fewer entries on the taskbar or window manager.[14][3][11] This approach is particularly beneficial for multitasking within productivity applications, where handling interrelated files is common.[15] MDI enhances workflow efficiency by enabling collective operations on multiple documents, such as closing all child windows at once or applying uniform arrangements like tiling across them, which is ideal for environments dealing with batches of related files.[3][15] Additionally, MDI promotes cross-platform consistency in application toolkits like Qt and Java Swing, where features such as QMdiArea and JDesktopPane allow developers to implement portable behaviors that behave uniformly across operating systems.[11][16]Disadvantages of MDI

One significant drawback of the multiple-document interface (MDI) is usability confusion arising from child windows that can overlap or become obscured within the parent window, complicating navigation and potentially hiding important content.[2] This issue is exacerbated by keyboard navigation challenges, as the system switcher (Alt-Tab) treats the MDI application as a single window for switching to other programs, but requires internal shortcuts like Ctrl+F6 to cycle between child windows, potentially trapping users within the application for document navigation.[3] Additionally, the differing behavior of MDI child windows compared to standard windows in single-document interface (SDI) applications requires users to learn separate windowing paradigms, increasing the cognitive load.[2] MDI also presents limitations in multi-monitor setups, where child windows are typically confined to the parent frame and cannot be freely moved or spanned across secondary displays without stretching the entire parent, which often leads to distorted layouts and reduced flexibility.[17] This restriction contrasts with modern workflows that rely on extended desktops for productivity, making MDI less adaptable to diverse hardware configurations.[2] Scalability becomes problematic in MDI as the number of open documents grows, resulting in crowded interfaces filled with overlapping child windows and exacerbating clutter from floating toolbars that lack containment outside the parent frame.[2] Without built-in organizational aids like tabs, managing dozens of documents devolves into a visually chaotic experience, diminishing efficiency for users handling large workloads.[18] Accessibility and learning curve issues further hinder MDI adoption, as its inconsistent window management deviates from SDI norms prevalent in many ecosystems, confusing users transitioning between applications and complicating integration with screen readers that struggle with nested window hierarchies.[2] Touch interfaces face similar hurdles, with imprecise gestures for manipulating layered child windows adding to the steep onboarding for non-expert users.[19] Critics point to MDI's evolution as evidence of its shortcomings, exemplified by Microsoft's transition in Office 2013 from pure MDI to SDI and tabbed hybrids in applications like Excel, primarily to resolve multi-monitor constraints and improve overall window independence.[17] This shift reflects broader recognition that MDI's rigid structure no longer aligns with dynamic, multi-tasking environments.[2]Platform Implementations

Microsoft Windows

The Multiple Document Interface (MDI) was introduced as a native feature in Microsoft Windows 3.0, released in 1990, to enable applications to manage multiple child windows within a single parent frame window.[3] This implementation standardized the handling of document-based workflows, allowing developers to create applications where users could open and switch between several documents without cluttering the desktop.[1] Core Windows APIs provide the foundation for MDI functionality in the Win32 subsystem. Developers create MDI child windows by calling theCreateMDIWindow function or sending the WM_MDICREATE message to the MDI client window, which establishes the parent-child relationship and initializes the child with specified properties like title and dimensions.[20] The MDI frame window relies on DefFrameProc for default message processing, handling events such as resizing and activation that the application's window procedure does not explicitly manage.[21] These APIs ensure that child windows are confined and clipped to the bounds of the parent frame, preventing them from extending beyond its client area.[3]

MDI behavior in Windows includes automatic menu merging, where the menu bar of the active child window replaces or integrates with the parent's menu when the child is focused, facilitating context-specific commands.[22] Additionally, only the parent window appears on the taskbar, with child windows managed internally via the application's window menu or controls, which consolidates task switching within the MDI container.[3]

Integration with development frameworks extends MDI support across Windows versions. In the Microsoft Foundation Classes (MFC) library, the CMDIFrameWnd class derives from CFrameWnd to implement MDI frame windows, providing methods for creating and managing child documents, including activation and cascading arrangements.[23] For .NET applications using Windows Forms, the IsMdiContainer property on a Form object transforms it into an MDI parent, enabling child forms to be added via the MdiChildren collection and supporting features like layout arrangement.[24] This support persists in Windows 11 as of 2025, with Win32 and managed APIs remaining available for both legacy and new applications, though developers must declare DPI awareness for proper scaling on high-resolution displays.[1] MDI containers also maintain compatibility with virtual desktops, treating the parent window as a single entity that spans desktop spaces without fragmenting child windows across them.[25]

Historically, MDI was a recommended pattern for document-centric applications in early Windows versions, such as Microsoft Office suites prior to 1995, where it was commonly used for multi-document handling in tools like Excel and Word.[3] By Windows 95, Microsoft began discouraging pure MDI in favor of single-document interfaces (SDI) or hybrid approaches, making it optional while retaining backward compatibility; modern Office versions, for instance, default to tabbed or SDI modes but allow MDI activation for legacy workflows.[1]

In toolkits like Visual Studio, MDI is directly utilized for designing and testing form-based applications, where developers set the IsMdiContainer property on a parent form and add child forms to simulate multi-document environments during runtime debugging.[26]