Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Muscle spindle

View on WikipediaThis article may incorporate text from a large language model. (October 2025) |

| Muscle spindle | |

|---|---|

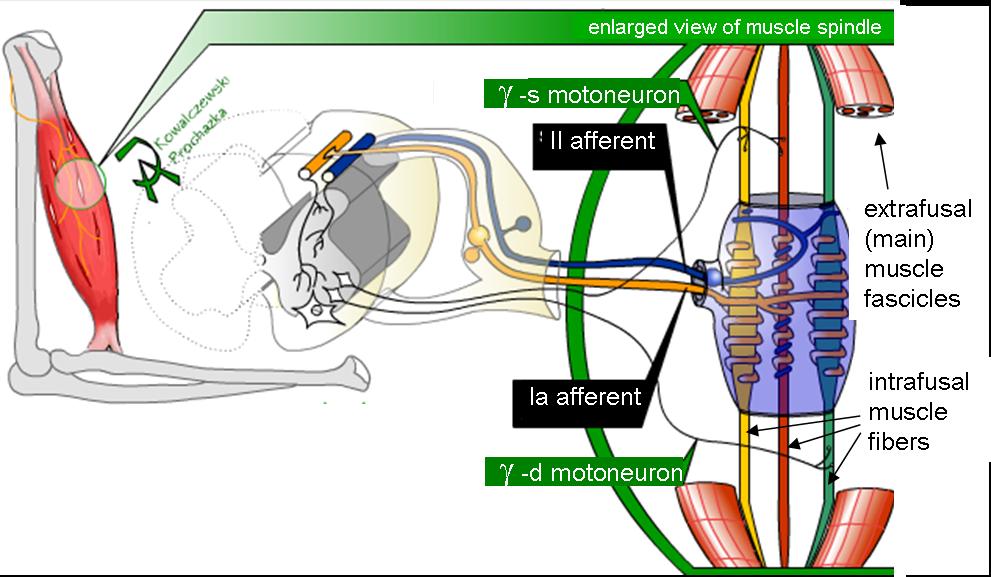

Mammalian muscle spindle showing typical position in a muscle (left), neuronal connections in spinal cord (middle) and expanded schematic (right). The spindle is a stretch receptor with its own motor supply consisting of several intrafusal muscle fibres. The sensory endings of a primary (group Ia) afferent and a secondary (group II) afferent coil around the non-contractile central portions of the intrafusal fibres. Gamma motor neurons activate the intrafusal muscle fibres, changing the resting firing rate and stretch-sensitivity of the afferents. [a] | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Muscle |

| System | Musculoskeletal |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | fusus neuromuscularis |

| MeSH | D009470 |

| TH | H3.11.06.0.00018 |

| FMA | 83607 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Muscle spindles are stretch receptors within the body of a skeletal muscle that primarily detect changes in the length of the muscle. They convey length information to the central nervous system via afferent nerve fibers. This information can be processed by the brain as proprioception. The responses of muscle spindles to changes in length also play an important role in regulating the contraction of muscles, for example, by activating motor neurons via the stretch reflex to resist muscle stretch.

The muscle spindle has both sensory and motor components.

- Sensory information conveyed by primary type Ia sensory fibers which spiral around muscle fibres within the spindle, and secondary type II sensory fibers

- Activation of muscle fibres within the spindle by up to a dozen gamma motor neurons and to a lesser extent by one or two beta motor neurons [1] .

Structure

[edit]Muscle spindles are found within the belly of a skeletal muscle. Muscle spindles are fusiform (spindle-shaped), and the specialized fibers that make up the muscle spindle are called intrafusal muscle fibers. The regular muscle fibers outside of the spindle are called extrafusal muscle fibers. Muscle spindles have a capsule of connective tissue, and run parallel to the extrafusal muscle fibers unlike Golgi tendon organs which are oriented in series.[citation needed]

Composition

[edit]Muscle spindles are composed of 5–14 muscle fibers, of which there are three types: dynamic nuclear bag fibers (bag1 fibers), static nuclear bag fibers (bag2 fibers), and nuclear chain fibers.[2][3]

Primary type Ia sensory fibers (large diameter) spiral around all intrafusal muscle fibres, ending near the middle of each fibre. Secondary type II sensory fibers (medium diameter) end adjacent to the central regions of the static bag and chain fibres.[3] These fibres send information by stretch-sensitive mechanically gated ion-channels of the axons.[4]

The motor part of the spindle is provided by motor neurons: up to a dozen gamma motor neurons also known as fusimotor neurons.[5] These activate the muscle fibres within the spindle. Gamma motor neurons supply only muscle fibres within the spindle, whereas beta motor neurons supply muscle fibres both within and outside of the spindle. Activation of the neurons causes a contraction and stiffening of the end parts of the muscle spindle muscle fibers.[citation needed]

Fusimotor neurons are classified as static or dynamic according to the type of muscle fibers they innervate and their effects on the responses of the Ia and II sensory neurons innervating the central, non-contractile part of the muscle spindle.

- The static axons innervate the chain or static bag2 fibers. They increase the firing rate of Ia and II afferents at a given muscle length (see schematic of fusimotor action below).

- The dynamic axons innervate the bag1 intrafusal muscle fibers. They increase the stretch-sensitivity of the Ia afferents by stiffening the bag1 intrafusal fibers.

Efferent nerve fibers of gamma motor neurons also terminate in muscle spindles; they make synapses at either or both of the ends of the intrafusal muscle fibers and regulate the sensitivity of the sensory afferents, which are located in the non-contractile central (equatorial) region.[6]

Function

[edit]Stretch reflex

[edit]When a muscle is stretched, primary type Ia sensory fibers of the muscle spindle respond to both changes in muscle length and velocity and transmit this activity to the spinal cord in the form of changes in the rate of action potentials. Likewise, secondary type II sensory fibers respond to muscle length changes (but with a smaller velocity-sensitive component) and transmit this signal to the spinal cord. The Ia afferent signals are transmitted monosynaptically to many alpha motor neurons of the receptor-bearing muscle. The reflexly evoked activity in the alpha motor neurons is then transmitted via their efferent axons to the extrafusal fibers of the muscle, which generate force and thereby resist the stretch. The Ia afferent signal is also transmitted polysynaptically through interneurons (Ia inhibitory interneurons), which inhibit alpha motorneurons of antagonist muscles, causing them to relax.[7]

Sensitivity modification

[edit]The function of the gamma motor neurons is not to supplement the force of muscle contraction provided by the extrafusal fibers, but to modify the sensitivity of the muscle spindle sensory afferents to stretch. Upon release of acetylcholine by the active gamma motor neuron, the end portions of the intrafusal muscle fibers contract, thus elongating the non-contractile central portions (see "fusimotor action" schematic below). This opens stretch-sensitive ion channels of the sensory endings, leading to an influx of sodium ions. This raises the resting potential of the endings, thereby increasing the probability of action potential firing, thus increasing the stretch-sensitivity of the muscle spindle afferents.

Recent transcriptomic and proteomic studies have identified unique gene expression profiles specific to muscle spindle regions. Distinct macrophage populations, known as muscle spindle macrophages (MSMPs), have been observed, suggesting an immunological component in muscle spindle maintenance and function.[8] Immunostaining and sequencing have enabled tissue-level identification of novel markers, contributing to an advanced cellular atlas of the muscle spindle. Regarding the structural-functional correlation; muscle spindle density is not uniform across the musculoskeletal system. Recent biomechanical modeling suggests that spindle abundance correlates with muscle fascicle length and fiber velocity during dynamic movement, emphasizing the relationship between muscle structure and proprioceptive requirements.[9]

How does the central nervous system control gamma fusimotor neurons? It has been difficult to record from gamma motor neurons during normal movement because they have very small axons. Several theories have been proposed, based on recordings from spindle afferents.

- 1) Alpha-gamma coactivation. Here it is posited that gamma motor neurons are activated in parallel with alpha motor neurons to maintain the firing of spindle afferents when the extrafusal muscles shorten.[10]

- 2) Fusimotor set: Gamma motor neurons are activated according to the novelty or difficulty of a task. Whereas static gamma motor neurons are continuously active during routine movements such as locomotion, dynamic gamma motorneurons tend to be activated more during difficult tasks, increasing Ia stretch-sensitivity.[11]

- 3) Fusimotor template of intended movement. Static gamma activity is a "temporal template" of the expected shortening and lengthening of the receptor-bearing muscle. Dynamic gamma activity turns on and off abruptly, sensitizing spindle afferents to the onset of muscle lengthening and departures from the intended movement trajectory.[12]

- 4) Goal-directed preparatory control. Dynamic gamma activity is adjusted proactively during movement preparation in order to facilitate execution of the planned action. For example, if the intended movement direction is associated with stretch of the spindle-bearing muscle, Ia afferent and stretch reflex sensitivity from this muscle is reduced. Gamma fusimotor control therefore allows for the independent preparatory tuning of muscle stiffness according to task goals.[13]

Development

[edit]Genetic pathways critical for spindle formation include neuregulin-1 signaling via ErbB receptors, which induce intrafusal fiber differentiation upon sensory innervation. Disruption of these pathways impairs proprioception, as seen in gene knockout models.[14]

It is also believed that muscle spindles play a critical role in sensorimotor development. Additionally, gain-of-function mutations in HRAS (e.g.: G12S) observed in Costello syndrome are associated with increased spindle number, providing insight into genetic regulation of spindle density.[15]

Clinical significance

[edit]Dysfunction in muscle spindle signaling has been implicated in sensory neuropathies and coordination disorders such as ataxia. Enhanced understanding of genetic mutations affecting spindle development (e.g. HRAS and Egr3-linked pathways) opens avenues for targeted therapies in proprioceptive deficits and neuromuscular diseases.

After stroke or spinal cord injury in humans, spastic hypertonia (spastic paralysis) often develops, whereby the stretch reflex in flexor muscles of the arms and extensor muscles of the legs is overly sensitive. This results in abnormal postures, stiffness and contractures. Hypertonia may be the result of over-sensitivity of alpha motor neurons and interneurons to the Ia and II afferent signals.[16]

Additional images

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Animated version: https://www.ualberta.ca/~aprochaz/research_interactive_receptor_model.html Arthur Prochazka's Lab, University of Alberta

References

[edit]- ^ Stifani, Nicolas (2014-10-09). "Motor neurons and the generation of spinal motor neuron diversity". Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 8: 293. doi:10.3389/fncel.2014.00293. ISSN 1662-5102. PMC 4191298. PMID 25346659.

- ^ Mancall, Elliott L; Brock, David G, eds. (2011). "Chapter 2 - Overview of the Microstructure of the Nervous System". Gray's Clinical Neuroanatomy: The Anatomic Basis for Clinical Neuroscience. Elsevier Saunders. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-4160-4705-6.

- ^ a b Pearson, Keir G; Gordon, James E (2013). "35 - Spinal Reflexes". In Kandel, Eric R; Schwartz, James H; Jessell, Thomas M; Siegelbaum, Steven A; Hudspeth, AJ (eds.). Principles of Neural Science (5th ed.). United States: McGraw-Hill. pp. 794–795. ISBN 978-0-07-139011-8.

- ^ Purves, Dale; Augustine, George J; Fitzpatrick, David; Hall, William C; Lamantia, Anthony Samuel; Mooney, Richard D; Platt, Michael L; White, Leonard E, eds. (2018). "Chapter 9 - The Somatosensory System: Touch and Proprioception". Neuroscience (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates. pp. 201–202. ISBN 978-1-60535-380-7.

- ^ Macefield, VG; Knellwolf, TP (1 August 2018). "Functional properties of human muscle spindles". Journal of Neurophysiology. 120 (2): 452–467. doi:10.1152/jn.00071.2018. PMID 29668385.

- ^ Hulliger M (1984). "The mammalian muscle spindle and its central control". Reviews of Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology, Volume 86. Vol. 101. pp. 1–110. doi:10.1007/bfb0027694. ISBN 978-3-540-13679-8. PMID 6240757.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Mukherjee, Angshuman; Chakravarty, Ambar (2010). "Spasticity Mechanisms – for the Clinician". Frontiers in Neurology. 1: 149. doi:10.3389/fneur.2010.00149. ISSN 1664-2295. PMC 3009478. PMID 21206767.

- ^ Yan, Yuyang; Antolin, Nuria; Zhou, Luming; Xu, Luyang; Vargas, Irene Lisa; Gomez, Carlos Daniel; Kong, Guiping; Palmisano, Ilaria; Yang, Yi; Chadwick, Jessica; Müller, Franziska; Bull, Anthony M. J.; Lo Celso, Cristina; Primiano, Guido; Servidei, Serenella (2025-01-16). "Macrophages excite muscle spindles with glutamate to bolster locomotion". Nature. 637 (8046): 698–707. Bibcode:2025Natur.637..698Y. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-08272-5. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 11735391. PMID 39633045.

- ^ Kissane, Roger W. P.; Charles, James P.; Banks, Robert W.; Bates, Karl T. (2022-06-08). "Skeletal muscle function underpins muscle spindle abundance". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 289 (1976) 20220622. doi:10.1098/rspb.2022.0622. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 9156921. PMID 35642368.

- ^ Vallbo AB, al-Falahe NA (February 1990). "Human muscle spindle response in a motor learning task". J. Physiol. 421: 553–68. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp017961. PMC 1190101. PMID 2140862.

- ^ Prochazka, A. (1996). "Proprioceptive feedback and movement regulation". In Rowell, L.; Sheperd, J.T. (eds.). Exercise: Regulation and Integration of Multiple Systems. Handbook of physiology. New York: American Physiological Society. pp. 89–127. ISBN 978-0-19-509174-8.

- ^ Taylor A, Durbaba R, Ellaway PH, Rawlinson S (March 2006). "Static and dynamic gamma-motor output to ankle flexor muscles during locomotion in the decerebrate cat". J. Physiol. 571 (Pt 3): 711–23. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2005.101634. PMC 1805796. PMID 16423858.

- ^ Papaioannou, S.; Dimitriou, M. (2021). "Goal-dependent tuning of muscle spindle receptors during movement preparation". Sci. Adv. 7 (9) eabe0401. Bibcode:2021SciA....7..401P. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abe0401. PMC 7904268. PMID 33627426.

- ^ "GEO Accession viewer". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2025-04-30.

- ^ "VCV000012602.66 - ClinVar - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2025-04-30.

- ^ Heckmann CJ, Gorassini MA, Bennett DJ (February 2005). "Persistent inward currents in motoneuron dendrites: implications for motor output". Muscle Nerve. 31 (2): 135–56. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.126.3583. doi:10.1002/mus.20261. PMID 15736297. S2CID 17828664.

External links

[edit]- Muscle+Spindles at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)