Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Desmin

View on Wikipedia

| DES | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | DES, CSM1, CSM2, LGMD2R, desmin, LGMD1D, CMD1F, CDCD3, LGMD1E | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 125660; MGI: 94885; HomoloGene: 56469; GeneCards: DES; OMA:DES - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Desmin is a protein that in humans is encoded by the DES gene.[5][6] Desmin is a muscle-specific, type III intermediate filament[7] that integrates the sarcolemma, Z disk, and nuclear membrane in sarcomeres and regulates sarcomere architecture.[8][9]

Structure

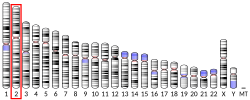

[edit]Desmin is a 53.5 kD protein composed of 470 amino acids, encoded by the human DES gene located on the long arm of chromosome 2.[10][11] There are three major domains to the desmin protein: a conserved alpha helix rod, a variable non alpha helix head, and a carboxy-terminal tail.[12] Desmin, as all intermediate filaments, shows no polarity when assembled.[12] The rod domain consists of 308 amino acids with parallel alpha helical coiled coil dimers and three linkers to disrupt it.[12] The rod domain connects to the head domain. The head domain 84 amino acids with many arginine, serine, and aromatic residues is important in filament assembly and dimer-dimer interactions.[12] The tail domain is responsible for the integration of filaments and interaction with proteins and organelles. Desmin is only expressed in vertebrates, however homologous proteins are found in many organisms.[12] Desmin is a subunit of intermediate filaments in cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle and smooth muscle tissue.[13] In cardiac muscle, desmin is present in Z-discs and intercalated discs. Desmin has been shown to interact with desmoplakin[14] and αB-crystallin.[15]

Function

[edit]Desmin was first described in 1976,[16] first purified in 1977,[17] the gene was cloned in 1989,[6] and the first knockout mouse was created in 1996. The function of desmin has been deduced through studies in knockout mice. Desmin is one of the earliest protein markers for muscle tissue in embryogenesis as it is detected in the somites.[12][18] Although it is present early in the development of muscle cells, it is only expressed at low levels, and increases as the cell nears terminal differentiation. A similar protein, vimentin, is present in higher amounts during embryogenesis while desmin is present in higher amounts after differentiation. This suggests that there may be some interaction between the two in determining muscle cell differentiation. However desmin knockout mice develop normally and only experience defects later in life.[13] Since desmin is expressed at a low level during differentiation another protein may be able to compensate for desmin's function early in development but not later on.[19]

In adult desmin-null mice, hearts from 10 week-old animals showed drastic alterations in muscle architecture, including a misalignment of myofibrils and disorganization and swelling of mitochondria; findings that were more severe in cardiac relative to skeletal muscle. Cardiac tissue also exhibited progressive necrosis and calcification of the myocardium.[20] A separate study examined this in more detail in cardiac tissue and found that murine hearts lacking desmin developed hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and chamber dilation combined with systolic dysfunction.[21] In adult muscle, desmin forms a scaffold around the Z-disk of the sarcomere and connects the Z-disk to the subsarcolemmal cytoskeleton.[22] It links the myofibrils laterally by connecting the Z-disks.[12] Through its connection to the sarcomere, desmin connects the contractile apparatus to the cell nucleus, mitochondria, and post-synaptic areas of motor endplates.[12] These connections maintain the structural and mechanical integrity of the cell during contraction while also helping in force transmission and longitudinal load bearing.[22][23]

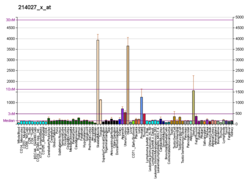

In human heart failure, desmin expression is upregulated, which has been hypothesized to be a defense mechanism in an attempt to maintain normal sarcomere alignment amidst disease pathogenesis.[24] There is some evidence that desmin may also connect the sarcomere to the extracellular matrix (ECM) through desmosomes which could be important in signalling between the ECM and the sarcomere which could regulate muscle contraction and movement.[23] Finally, desmin may be important in mitochondria function. When desmin is not functioning properly there is improper mitochondrial distribution, number, morphology and function.[25][26] Since desmin links the mitochondria to the sarcomere it may transmit information about contractions and energy need and through this regulate the aerobic respiration rate of the muscle cell.

Clinical significance

[edit]Desmin-related myofibrillar myopathy (DRM or desminopathy) is a subgroup of the myofibrillar myopathy diseases [27] and is the result of a mutation in the gene that codes for desmin which by changing the protein structure [28] prevents it from forming protein filaments, and rather, forms aggregates of desmin and other proteins throughout the cell.[8][12] Desmin (DES) mutations have been associated with restrictive,[29] dilated,[30][31] idiopathic,[32][33] arrhythmogenic [34][35][36][37] and non-compaction cardimyopathy.[38][39] Even within the same family the observed cardiac phenotype could be broad and diverse. The N-terminal part of the 1A desmin subdomain is a genetic hot spot region for mutations affecting filament assembly.[40][41] Some of these DES mutations cause an aggregation of desmin within the cytoplasm.[41][42][43] Some mutations like p.A120D or p.R127P were discovered in families, where several members had sudden cardiac death.[44] In addition, DES mutations cause frequently cardiac conduction diseases.[45]

Desmin has been evaluated for role in assessing the depth of invasion of urothelial carcinoma in TURBT specimens.[46]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000175084 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000026208 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Muñoz-Mármol AM, Strasser G, Isamat M, Coulombe PA, Yang Y, Roca X, et al. (September 1998). "A dysfunctional desmin mutation in a patient with severe generalized myopathy". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (19): 11312–11317. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9511312M. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.19.11312. PMC 21639. PMID 9736733.

- ^ a b Li ZL, Lilienbaum A, Butler-Browne G, Paulin D (May 1989). "Human desmin-coding gene: complete nucleotide sequence, characterization and regulation of expression during myogenesis and development". Gene. 78 (2): 243–254. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(89)90227-8. PMID 2673923.

- ^ "Desmin", The Human Protein Atlas. Proteinatlas.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-29.

- ^ a b Brodehl A, Gaertner-Rommel A, Milting H (August 2018). "Molecular insights into cardiomyopathies associated with desmin (DES) mutations". Biophysical Reviews. 10 (4): 983–1006. doi:10.1007/s12551-018-0429-0. PMC 6082305. PMID 29926427.

- ^ Sequeira V, Nijenkamp LL, Regan JA, van der Velden J (February 2014). "The physiological role of cardiac cytoskeleton and its alterations in heart failure". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1838 (2): 700–722. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.07.011. PMID 23860255.

- ^ "Mass spectrometry characterization of human DES at COPaKB". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-03-19.

- ^ Zong NC, Li H, Li H, Lam MP, Jimenez RC, Kim CS, et al. (October 2013). "Integration of cardiac proteome biology and medicine by a specialized knowledgebase". Circulation Research. 113 (9): 1043–1053. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301151. PMC 4076475. PMID 23965338.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bär H, Strelkov SV, Sjöberg G, Aebi U, Herrmann H (November 2004). "The biology of desmin filaments: how do mutations affect their structure, assembly, and organisation?". Journal of Structural Biology. 148 (2): 137–152. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2004.04.003. PMID 15477095.

- ^ a b Li Z, Mericskay M, Agbulut O, Butler-Browne G, Carlsson L, Thornell LE, et al. (October 1997). "Desmin is essential for the tensile strength and integrity of myofibrils but not for myogenic commitment, differentiation, and fusion of skeletal muscle". The Journal of Cell Biology. 139 (1): 129–144. doi:10.1083/jcb.139.1.129. PMC 2139820. PMID 9314534.

- ^ Meng JJ, Bornslaeger EA, Green KJ, Steinert PM, Ip W (August 1997). "Two-hybrid analysis reveals fundamental differences in direct interactions between desmoplakin and cell type-specific intermediate filaments". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (34): 21495–21503. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.34.21495. PMID 9261168.

- ^ Bennardini F, Wrzosek A, Chiesi M (August 1992). "Alpha B-crystallin in cardiac tissue. Association with actin and desmin filaments". Circulation Research. 71 (2): 288–294. doi:10.1161/01.res.71.2.288. PMID 1628387.

- ^ Lazarides E, Hubbard BD (December 1976). "Immunological characterization of the subunit of the 100 A filaments from muscle cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 73 (12): 4344–4348. doi:10.1073/pnas.73.12.4344. PMC 431448. PMID 1069986.

- ^ Izant JG, Lazarides E (April 1977). "Invariance and heterogeneity in the major structural and regulatory proteins of chick muscle cells revealed by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 74 (4): 1450–1454. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.1450I. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.4.1450. PMC 430794. PMID 266185.

- ^ Costa ML, Escaleira R, Cataldo A, Oliveira F, Mermelstein CS (December 2004). "Desmin: molecular interactions and putative functions of the muscle intermediate filament protein". Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 37 (12): 1819–1830. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2004001200007. PMID 15558188.

- ^ Stoeckert C (1997-03-16). "Dystrophin". Catalogue of Regulatory Elements. University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 2007-06-08. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Milner DJ, Weitzer G, Tran D, Bradley A, Capetanaki Y (September 1996). "Disruption of muscle architecture and myocardial degeneration in mice lacking desmin". The Journal of Cell Biology. 134 (5): 1255–1270. doi:10.1083/jcb.134.5.1255. PMC 2120972. PMID 8794866.

- ^ Milner DJ, Taffet GE, Wang X, Pham T, Tamura T, Hartley C, et al. (November 1999). "The absence of desmin leads to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and cardiac dilation with compromised systolic function". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 31 (11): 2063–2076. doi:10.1006/jmcc.1999.1037. PMID 10591032.

- ^ a b Paulin D, Li Z (November 2004). "Desmin: a major intermediate filament protein essential for the structural integrity and function of muscle". Experimental Cell Research. 301 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.08.004. PMID 15501438.

- ^ a b Shah SB, Davis J, Weisleder N, Kostavassili I, McCulloch AD, Ralston E, et al. (May 2004). "Structural and functional roles of desmin in mouse skeletal muscle during passive deformation". Biophysical Journal. 86 (5): 2993–3008. Bibcode:2004BpJ....86.2993S. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74349-0. PMC 1304166. PMID 15111414.

- ^ Heling A, Zimmermann R, Kostin S, Maeno Y, Hein S, Devaux B, et al. (April 2000). "Increased expression of cytoskeletal, linkage, and extracellular proteins in failing human myocardium". Circulation Research. 86 (8): 846–853. doi:10.1161/01.res.86.8.846. PMID 10785506.

- ^ Milner DJ, Mavroidis M, Weisleder N, Capetanaki Y (September 2000). "Desmin cytoskeleton linked to muscle mitochondrial distribution and respiratory function". The Journal of Cell Biology. 150 (6): 1283–1298. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.273.9903. doi:10.1083/jcb.150.6.1283. PMC 2150713. PMID 10995435.

- ^ Goldfarb LG, Vicart P, Goebel HH, Dalakas MC (April 2004). "Desmin myopathy". Brain. 127 (Pt 4): 723–734. doi:10.1093/brain/awh033. PMID 14724127.

- ^ Fichna JP, Maruszak A, Żekanowski C (November 2018). "Myofibrillar myopathy in the genomic context". Journal of Applied Genetics. 59 (4): 431–439. doi:10.1007/s13353-018-0463-4. PMID 30203143.

- ^ Fichna JP, Karolczak J, Potulska-Chromik A, Miszta P, Berdynski M, Sikorska A, et al. (December 2014). "Two desmin gene mutations associated with myofibrillar myopathies in Polish families". PLOS ONE. 9 (12) e115470. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k5470F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115470. PMC 4277352. PMID 25541946.

- ^ Brodehl A, Pour Hakimi SA, Stanasiuk C, Ratnavadivel S, Hendig D, Gaertner A, et al. (November 2019). "Restrictive Cardiomyopathy is Caused by a Novel Homozygous Desmin (DES) Mutation p.Y122H Leading to a Severe Filament Assembly Defect". Genes. 10 (11): 918. doi:10.3390/genes10110918. PMC 6896098. PMID 31718026.

- ^ Fischer B, Dittmann S, Brodehl A, Unger A, Stallmeyer B, Paul M, et al. (April 2021). "Functional characterization of novel alpha-helical rod domain desmin (DES) pathogenic variants associated with dilated cardiomyopathy, atrioventricular block and a risk for sudden cardiac death". International Journal of Cardiology. 329: 167–174. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.12.050. PMID 33373648. S2CID 229719883.

- ^ Brodehl A, Dieding M, Biere N, Unger A, Klauke B, Walhorn V, et al. (February 2016). "Functional characterization of the novel DES mutation p.L136P associated with dilated cardiomyopathy reveals a dominant filament assembly defect". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 91: 207–214. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.12.015. PMID 26724190.

- ^ Li D, Tapscoft T, Gonzalez O, Burch PE, Quiñones MA, Zoghbi WA, et al. (August 1999). "Desmin mutation responsible for idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy". Circulation. 100 (5): 461–464. doi:10.1161/01.cir.100.5.461. PMID 10430757.

- ^ Goldfarb LG, Park KY, Cervenáková L, Gorokhova S, Lee HS, Vasconcelos O, et al. (August 1998). "Missense mutations in desmin associated with familial cardiac and skeletal myopathy". Nature Genetics. 19 (4): 402–403. doi:10.1038/1300. PMID 9697706. S2CID 23313873.

- ^ Protonotarios A, Brodehl A, Asimaki A, Jager J, Quinn E, Stanasiuk C, et al. (June 2021). "The Novel Desmin Variant p.Leu115Ile Is Associated With a Unique Form of Biventricular Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy". The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 37 (6): 857–866. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2020.11.017. PMID 33290826. S2CID 228078648.

- ^ Bermúdez-Jiménez FJ, Carriel V, Brodehl A, Alaminos M, Campos A, Schirmer I, et al. (April 2018). "Novel Desmin Mutation p.Glu401Asp Impairs Filament Formation, Disrupts Cell Membrane Integrity, and Causes Severe Arrhythmogenic Left Ventricular Cardiomyopathy/Dysplasia". Circulation. 137 (15): 1595–1610. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028719. hdl:10481/89514. PMID 29212896. S2CID 4715358.

- ^ Klauke B, Kossmann S, Gaertner A, Brand K, Stork I, Brodehl A, et al. (December 2010). "De novo desmin-mutation N116S is associated with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy". Human Molecular Genetics. 19 (23): 4595–4607. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq387. PMID 20829228.

- ^ Lorenzon A, Beffagna G, Bauce B, De Bortoli M, Li Mura IE, Calore M, et al. (February 2013). "Desmin mutations and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy". The American Journal of Cardiology. 111 (3): 400–405. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.10.017. PMC 3554957. PMID 23168288.

- ^ Kulikova O, Brodehl A, Kiseleva A, Myasnikov R, Meshkov A, Stanasiuk C, et al. (January 2021). "The Desmin (DES) Mutation p.A337P Is Associated with Left-Ventricular Non-Compaction Cardiomyopathy". Genes. 12 (1): 121. doi:10.3390/genes12010121. PMC 7835827. PMID 33478057.

- ^ Marakhonov AV, Brodehl A, Myasnikov RP, Sparber PA, Kiseleva AV, Kulikova OV, et al. (June 2019). "Noncompaction cardiomyopathy is caused by a novel in-frame desmin (DES) deletion mutation within the 1A coiled-coil rod segment leading to a severe filament assembly defect". Human Mutation. 40 (6): 734–741. doi:10.1002/humu.23747. PMID 30908796. S2CID 85515283.

- ^ Voß S, Walhorn V, Holler S, Gärtner A, Pohl G, Tiesmeier J, et al. (January 2025). "Functional impact of the head domain variants of DES (Desmin) on filament assembly". Genes & Diseases. 12 (1) 101238. doi:10.1016/j.gendis.2024.101238. PMC 11620975. PMID 39650696.

- ^ a b Borchers A, Pieler T (November 2010). "Programming pluripotent precursor cells derived from Xenopus embryos to generate specific tissues and organs". Genes. 1 (3): 413–426. doi:10.3390/cells11233906. PMC 9738904. PMID 36497166.

- ^ Brodehl A, Hedde PN, Dieding M, Fatima A, Walhorn V, Gayda S, et al. (May 2012). "Dual color photoactivation localization microscopy of cardiomyopathy-associated desmin mutants". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 287 (19): 16047–16057. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.313841. PMC 3346104. PMID 22403400.

- ^ Brodehl A, Ebbinghaus H, Gaertner-Rommel A, Stanasiuk C, Klauke B, Milting H (May 2019). "Functional analysis of DES-p.L398P and RBM20-p.R636C". Genetics in Medicine. 21 (5): 1246–1247. doi:10.1038/s41436-018-0291-2. PMID 30262925. S2CID 52877855.

- ^ Brodehl A, Dieding M, Klauke B, Dec E, Madaan S, Huang T, et al. (December 2013). "The novel desmin mutant p.A120D impairs filament formation, prevents intercalated disk localization, and causes sudden cardiac death". Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 6 (6): 615–623. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000103. PMID 24200904.

- ^ Schirmer I, Dieding M, Klauke B, Brodehl A, Gaertner-Rommel A, Walhorn V, et al. (March 2018). "A novel desmin (DES) indel mutation causes severe atypical cardiomyopathy in combination with atrioventricular block and skeletal myopathy". Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine. 6 (2): 288–293. doi:10.1002/mgg3.358. PMC 5902401. PMID 29274115.

- ^ Saha K, Saha A, Datta C, Chatterjee U, Ray S, Bera M (2014). "Does desmin immunohistochemistry have a role in assessing stage of urothelial carcinoma in transurethral resection of bladder tumor specimens?". Clinical Cancer Investigation Journal. 3 (6): 502. doi:10.4103/2278-0513.142634.

External links

[edit]- GeneReviews/NIH/NCBI/UW entry on Myofibrillar Myopathy

- Desmin at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- LOVD mutation database: DES