Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Anatomical terms of muscle

View on Wikipedia |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Anatomical terminology |

|---|

Anatomical terminology is used to uniquely describe aspects of skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle such as their actions, structure, size, and location.

Types

[edit]There are three types of muscle tissue in the body: skeletal, smooth, and cardiac.

Skeletal muscle

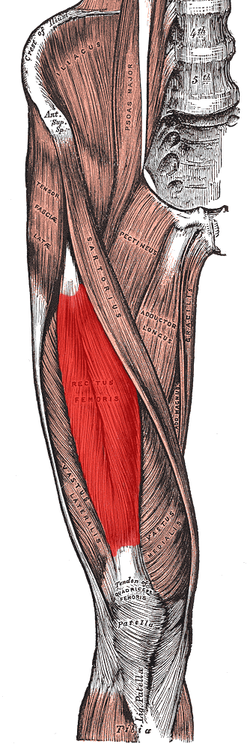

[edit]Skeletal muscle, or "voluntary muscle", is a striated muscle tissue that primarily joins to bone with tendons. Skeletal muscle enables movement of bones, and maintains posture.[1] The widest part of a muscle that pulls on the tendons is known as the belly.

Muscle slip

[edit]A muscle slip is a slip of muscle that can either be an anatomical variant,[2] or a branching of a muscle as in rib connections of the serratus anterior muscle.

Smooth muscle

[edit]Smooth muscle is involuntary and found in parts of the body where it conveys action without conscious intent. The majority of this type of muscle tissue is found in the digestive and urinary systems where it acts by propelling forward food, chyme, and feces in the former and urine in the latter. Other places smooth muscle can be found are within the uterus, where it helps facilitate birth, and the eye, where the pupillary sphincter controls pupil size.[3]

Cardiac muscle

[edit]Cardiac muscle is specific to the heart. It is also involuntary in its movement, and is additionally self-excitatory, contracting without outside stimuli.[4]

Actions of skeletal muscle

[edit]As well as anatomical terms of motion, which describe the motion made by a muscle, unique terminology is used to describe the action of a set of muscles.

Agonists and antagonists

[edit]Agonist muscles and antagonist muscles are muscles that cause or inhibit a movement.[5]

Agonist muscles are also called prime movers since they produce most of the force, and control of an action.[6] Agonists cause a movement to occur through their own activation.[7] For example, the triceps brachii contracts, producing a shortening (concentric) contraction, during the up phase of a push-up (elbow extension). During the down phase of a push-up, the same triceps brachii actively controls elbow flexion while producing a lengthening (eccentric) contraction. It is still the agonist, because while resisting gravity during relaxing, the triceps brachii continues to be the prime mover, or controller, of the joint action.

Another example is the dumb-bell curl at the elbow. The elbow flexor group is the agonist, shortening during the lifting phase (elbow flexion). During the lowering phase the elbow flexor muscles lengthen, remaining the agonists because they are controlling the load and the movement (elbow extension). For both the lifting and lowering phase, the "elbow extensor" muscles are the antagonists (see below). They lengthen during the dumbbell lifting phase and shorten during the dumbbell lowering phase. Here it is important to understand that it is common practice to give a name to a muscle group (e.g. elbow flexors) based on the joint action they produce during a shortening contraction. However, this naming convention does not mean they are only agonists during shortening. This term typically describes the function of skeletal muscles.[8]

Antagonist muscles are simply the muscles that produce an opposing joint torque to the agonist muscles.[9] This torque can aid in controlling a motion. The opposing torque can slow movement down - especially in the case of a ballistic movement. For example, during a very rapid (ballistic) discrete movement of the elbow, such as throwing a dart, the triceps muscles will be activated very briefly and strongly (in a "burst") to rapidly accelerate the extension movement at the elbow, followed almost immediately by a "burst" of activation to the elbow flexor muscles that decelerates the elbow movement to arrive at a quick stop. To use an automotive analogy, this would be similar to pressing the accelerator pedal rapidly and then immediately pressing the brake. Antagonism is not an intrinsic property of a particular muscle or muscle group; it is a role that a muscle plays depending on which muscle is currently the agonist. During slower joint actions that involve gravity, just as with the agonist muscle, the antagonist muscle can shorten and lengthen. Using the example of the triceps brachii during a push-up, the elbow flexor muscles are the antagonists at the elbow during both the up phase and down phase of the movement. During the dumbbell curl, the elbow extensors are the antagonists for both the lifting and lowering phases.[10]

Antagonistic pairs

[edit]

Antagonist and agonist muscles often occur in pairs, called antagonistic pairs. As one muscle contracts, the other relaxes. An example of an antagonistic pair is the biceps and triceps; to contract, the triceps relaxes while the biceps contracts to lift the arm. "Reverse motions" need antagonistic pairs located in opposite sides of a joint or bone, including abductor-adductor pairs and flexor-extensor pairs. These consist of an extensor muscle, which "opens" the joint (by increasing the angle between the two bones) and a flexor muscle, which does the opposite by decreasing the angle between two bones.

However, muscles do not always work this way; sometimes agonists and antagonists contract at the same time to produce force, as per Lombard's paradox. Also, sometimes during a joint action controlled by an agonist muscle, the antagonist will be slightly activated, naturally. This occurs normally and is not considered to be a problem unless it is excessive or uncontrolled and disturbs the control of the joint action. This is called agonist/antagonist co-activation and serves to mechanically stiffen the joint.

Not all muscles are paired in this way. An example of an exception is the deltoid.[11]

Synergists

[edit]

Synergist muscles also called fixators, act around a joint to help the action of an agonist muscle. Synergist muscles can also act to counter or neutralize the force of an agonist and are also known as neutralizers when they do this.[12] As neutralizers they help to cancel out or neutralize extra motion produced from the agonists to ensure that the force generated works within the desired plane of motion.

Muscle fibers can only contract up to 40% of their fully stretched length. [citation needed] Thus the short fibers of pennate muscles are more suitable where power rather than range of contraction is required. This limitation in the range of contraction affects all muscles, and those that act over several joints may be unable to shorten sufficiently to produce the full range of movement at all of them simultaneously (active insufficiency, e.g., the fingers cannot be fully flexed when the wrist is also flexed). Likewise, the opposing muscles may be unable to stretch sufficiently to allow such movement to take place (passive insufficiency). For both these reasons, it is often essential to use other synergists, in this type of action to fix certain of the joints so that others can be moved effectively, e.g., fixation of the wrist during full flexion of the fingers in clenching the fist. Synergists are muscles that facilitate the fixation action.

There is an important difference between a helping synergist muscle and a true synergist muscle. A true synergist muscle is one that only neutralizes an undesired joint action, whereas a helping synergist is one that neutralizes an undesired action but also assists with the desired action. [citation needed]

Neutralizer action

[edit]A muscle that fixes or holds a bone so that the agonist can carry out the intended movement is said to have a neutralizing action. A good famous example of this are the hamstrings; the semitendinosus and semimembranosus muscles perform knee flexion and knee internal rotation whereas the biceps femoris carries out knee flexion and knee external rotation. For the knee to flex while not rotating in either direction, all three muscles contract to stabilize the knee while it moves in the desired way.

Composite muscle

[edit]Composite or hybrid muscles have more than one set of fibers that perform the same function, and are usually supplied by different nerves for different set of fibers. For example, the tongue itself is a composite muscle made up of various components like longitudinal, transverse, horizontal muscles with different parts innervated from a different nerve supply.

Muscle naming

[edit]

There are a number of terms used in the naming of muscles including those relating to size, shape, action, location, their orientation, and their number of heads.

- By size

- brevis means short; longus means long; major means large; maximus means largest; minor means small, and minimus smallest. These terms are often used after the particular muscle such as gluteus maximus, and gluteus minimus.[13]

- By shape

- deltoid means triangular; quadratus means having four sides; rhomboideus means having a rhomboid shape; teres means round or cylindrical, trapezius means having a trapezoid shape, rectus means straight. Examples are the pronator teres, the pronator quadratus and the rectus abdominis.[13]

- By action

- abductor moving away from the midline; adductor moving towards the midline; depressor moving downwards; elevator moving upwards; flexor moving that decreases an angle; extensor moving that increase an angle or straightens; pronator moving to face down; supinator moving to face upwards;[13] Internal rotator rotating towards the body; external rotator rotating away from the body.

Form

[edit]

Insertion and origin

[edit]The insertion and origin of a muscle are the two places where it is anchored, one at each end. The connective tissue of the attachment is called an enthesis.

Origin

[edit]The origin of a muscle is the bone, typically proximal, which has greater mass and is more stable during a contraction than a muscle's insertion.[14] For example, with the latissimus dorsi muscle, the origin site is the torso, and the insertion is the arm. When this muscle contracts, normally the arm moves due to having less mass than the torso. This is the case when grabbing objects lighter than the body, as in the typical use of a lat pull down machine. This can be reversed however, such as in a chin up where the torso moves up to meet the arm.

The head of a muscle, also called caput musculi is the part at the end of a muscle at its origin, where it attaches to a fixed bone. Some muscles such as the biceps have more than one head.

Insertion

[edit]The insertion of a muscle is the structure that it attaches to and tends to be moved by the contraction of the muscle.[15] This may be a bone, a tendon or the subcutaneous dermal connective tissue. Insertions are usually connections of muscle via tendon to bone.[16] The insertion is a bone that tends to be distal, have less mass, and greater motion than the origin during a contraction.

Intrinsic and extrinsic muscles

[edit]Intrinsic muscles have their origin in the part of the body that they act on, and are contained within that part.[17] Extrinsic muscles have their origin outside of the part of the body that they act on.[18] Examples are the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the tongue, and those of the hand.

Muscle fibres

[edit]

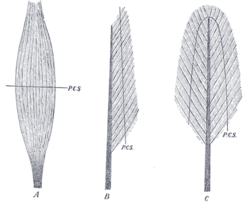

A: fusiform. B: unipennate. C: bipennate.

(PCS: physiological cross-section)

Muscles may also be described by the direction that the muscle fibres run, in their muscle architecture.

- Fusiform muscles have fibres that run parallel to the length of the muscle, and are spindle-shaped.[19] For example, the pronator teres muscle of the forearm.

- Unipennate muscles have fibres that run the entire length of only one side of a muscle, like a quill pen. For example, the fibularis muscles.

- Bipennate muscles consist of two rows of oblique muscle fibres, facing in opposite diagonal directions, converging on a central tendon. Bipennate muscle is stronger than both unipennate muscle and fusiform muscle, due to a larger physiological cross-sectional area. Bipennate muscle shortens less than unipennate muscle but develops greater tension when it does, translated into greater power but less range of motion. Pennate muscles generally also tire easily. Examples of bipennate muscles are the rectus femoris muscle of the thigh, and the stapedius muscle of the middle ear.

State

[edit]Hypertrophy and atrophy

[edit]

Hypertrophy is increase in muscle size from an increase in size of individual muscle cells. This usually occurs as a result of exercise.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Skeletal Muscle

- ^ Stimec, Bojan V.; Dash, Jérémy; Assal, Mathieu; Stern, Richard; Fasel, Jean H. D. (1 May 2018). "Additional muscular slip of the flexor digitorum longus muscle to the fifth toe". Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy. 40 (5): 533–535. doi:10.1007/s00276-018-1991-7. PMID 29473094. S2CID 3456242. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ Smooth Muscle

- ^ Cardiac Muscle

- ^ "Interactions of skeletal muscles their fascicle arrangement and their lever-systems". Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Saladin, Kenneth S. (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 236–241. ISBN 9780071222075.

- ^ Taber 2001, pp. "Agonist".

- ^ Baechle, Thomas (2008). Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. USA: National Strength and Conditioning Association. ISBN 978-0-7360-8465-9.

- ^ Taber 2001, pp. "Antagonist".

- ^ Walker, H. Kenneth (1990), Walker, H. Kenneth; Hall, W. Dallas; Hurst, J. Willis (eds.), "Deep Tendon Reflexes", Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations (3rd ed.), Boston: Butterworths, ISBN 978-0-409-90077-4, PMID 21250237, retrieved 2024-02-19

- ^ Purves, D; Augustine, GJ (2001). "Neural Circuits". NCBI. Sinauer Association.

- ^ "9.6C: How Skeletal Muscles Produce Movements". Medicine LibreTexts. 19 July 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Saladin, Kenneth S. (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 265. ISBN 9780071222075.

- ^ OED 1989, "origin".

- ^ Taber 2001, "insertion".

- ^ Martini, Frederic; William C. Ober; Claire W. Garrison; Kathleen Welch; Ralph T. Hutchings (2001). Fundamentals of Anatomy and Physiology, 5th Ed. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0130172928.

- ^ "Definition of INTRINSIC". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "Definition of EXTRINSIC". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Taber 2001, "Fusiform".

- Books

- Taber, Clarence Wilbur; Thomas, Clayton L.; Venes, Donald (2001). Taber's cyclopedic medical dictionary (Ed. 19, illustrated in full color ed.). Philadelphia: F.A.Davis Co. ISBN 0-8036-0655-9. ISSN 1065-1357.

- J. A. Simpson, ed. (1989). The Oxford English dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198611868.

Anatomical terms of muscle

View on GrokipediaMuscle Types

Skeletal Muscles

Skeletal muscles constitute the predominant type of muscle tissue in the human body, consisting of long, cylindrical, multinucleated fibers that exhibit a striated appearance due to the regular arrangement of sarcomeres, which create alternating light and dark bands under microscopic examination.[5][6] These fibers are under voluntary control, innervated by the somatic nervous system, allowing conscious initiation of contraction.[7] Typically attached to bones via tendons or aponeuroses, skeletal muscles facilitate the transmission of force to produce coordinated movements.[1] The architectural organization of skeletal muscle includes three concentric layers of connective tissue that provide structural support and facilitate force transmission. The epimysium, a dense outer sheath of collagen, encases the entire muscle belly, while the perimysium divides the muscle into bundles or fascicles of fibers.[8] The endomysium, the finest layer, directly surrounds each individual muscle fiber, integrating with the sarcolemma to maintain fiber integrity during contraction.[9] These connective tissues also extend to form tendons that anchor the muscle to skeletal elements. Skeletal muscles are essential for locomotion, enabling the precise control of body segments through antagonistic and synergistic actions.[10] They also contribute to postural stability by counteracting gravitational forces and joint stabilization during dynamic activities. Additionally, their metabolic activity during contraction generates significant heat, aiding in thermoregulation and overall homeostasis.[11] The designation "skeletal" reflects their primary attachment to the bony skeleton, distinguishing them from other muscle types. Early anatomical descriptions of these voluntary, bone-attached muscles trace back to ancient Roman physician Galen (c. 129–c. 216 CE), who detailed their role in purposeful motion driven by neural impulses from the brain.[12]Smooth Muscles

Smooth muscle, also known as visceral muscle, is a type of involuntary muscle tissue composed of non-striated, spindle-shaped fibers that contain a single central nucleus and are controlled by the autonomic nervous system.[13] Unlike skeletal muscle, which allows voluntary movement, smooth muscle operates without conscious control, enabling automatic regulation of internal organ functions.[14] Smooth muscle is classified into two main types based on its organization and contraction behavior: unitary smooth muscle, which functions like a syncytium due to gap junctions connecting cells for coordinated, wave-like contractions, and multiunit smooth muscle, where individual fibers contract independently in response to neural stimulation, providing finer control.[14] Unitary smooth muscle is prevalent in organs like the digestive tract, while multiunit types are found in structures such as the iris and large arteries.[13] Structurally, smooth muscle lacks the organized sarcomeres of striated muscle, instead relying on dense bodies—specialized protein aggregates that anchor actin filaments to the cell membrane and facilitate force transmission during contraction.[13] These cells are surrounded by a fine network of connective tissue, but they do not possess an epimysium, the outer sheath typical of skeletal muscles.[13] The actin and myosin filaments are arranged obliquely, allowing for smooth, tapered contractions without the banded appearance of striated tissue.[13] Smooth muscle is primarily located in the walls of hollow visceral organs and structures, where it performs essential regulatory functions. In blood vessels, it mediates vasoconstriction and vasodilation to control blood flow and pressure.[14] In the digestive tract, it drives peristalsis, the rhythmic propulsion of contents through the gastrointestinal system.[14] Additionally, in the airways, it enables bronchoconstriction to adjust air passage diameter, as seen in responses to irritants or allergens.[14] The contraction of smooth muscle is characteristically slow and sustained, differing from the rapid twitches of skeletal muscle, and is initiated through the calmodulin-myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) pathway.[14] Upon stimulation, calcium ions enter the cell and bind to calmodulin, activating MLCK, which phosphorylates the myosin light chain to permit actin-myosin cross-bridge formation and force generation.[14] This mechanism supports prolonged tone without fatigue, ideal for maintaining organ homeostasis.[13]Cardiac Muscles

Cardiac muscle, also known as myocardium, is a specialized type of striated muscle tissue found exclusively in the walls of the heart, where it forms the contractile layer responsible for pumping blood throughout the circulatory system.[15] It consists of short, branched cylindrical fibers that interconnect to create a functional syncytium, allowing for coordinated and efficient contractions across the heart. Each fiber, or cardiomyocyte, typically contains a single, centrally located nucleus, though some cells may be binucleated, and the cells are smaller than those in skeletal muscle.[15] The striated appearance arises from the organized sarcomeres containing actin and myosin filaments, a feature shared with skeletal muscle but adapted for continuous, rhythmic activity in the heart.[15] A defining structural feature of cardiac muscle is the intercalated disc, a complex junction that links adjacent cardiomyocytes end-to-end. These discs incorporate desmosomes for mechanical adhesion, which anchor the cells together to withstand the forces of contraction, and gap junctions that permit the rapid passage of ions and electrical impulses between cells, ensuring synchronized depolarization and contraction across the myocardium.[15] Cardiac fibers also possess abundant mitochondria, occupying up to 33% of the cell volume, which support high-energy demands through aerobic respiration, and larger T-tubules that form dyads with the sarcoplasmic reticulum to facilitate efficient calcium handling during excitation-contraction coupling.[16] Functionally, cardiac muscle operates under involuntary control via the autonomic nervous system, yet it exhibits autorhythmicity, the ability to self-generate action potentials without external neural input, primarily driven by specialized pacemaker cells in the sinoatrial node located in the right atrium.[16] This intrinsic pacemaker sets the heart's rhythm at 60–100 beats per minute, initiating electrical impulses that propagate through the cardiac conduction system, including conducting cells like those in the atrioventricular node and Purkinje fibers.[17] The contraction phase, known as systole, ejects blood from the heart chambers, while the relaxation phase, diastole, allows refilling; these cycles are myogenic, meaning the muscle initiates contractions independently due to its autorhythmic properties.[16] Cardiac muscle is highly resistant to fatigue, owing to its reliance on oxidative metabolism and dense mitochondrial network, enabling nonstop activity without the rest periods required by other muscle types.[16]Muscle Attachments and Morphology

Origin and Insertion

In skeletal muscle anatomy, the origin refers to the fixed or proximal attachment point of a muscle, typically on a relatively stationary bone or structure that remains stable during contraction.[18] This end resists the pull of the muscle, serving as the anchor from which movement originates. In contrast, the insertion is the distal or movable attachment point, usually on a bone or structure that is displaced when the muscle contracts, allowing for the intended action such as flexion or extension.[19] These terms emphasize the proximal-distal orientation along the body's longitudinal axis, with proximal indicating closeness to the trunk and distal farther away.[20] Muscles connect to their origins and insertions through various connective tissues, including tendons—dense, cord-like structures of collagen that transmit force to bone—or broader, sheet-like aponeuroses that distribute attachment over a wider area.[21] In some cases, attachments occur directly to the periosteum, the fibrous membrane covering bone, without intervening tendons, particularly in muscles with pennate architectures.[22] The distinction between origin and insertion is determined by observing the muscle's behavior during movement: the origin is identified as the end that remains fixed relative to the body's midline or the joint's axis, while the insertion moves toward the origin upon contraction.[23] A classic example is the biceps brachii muscle, which originates proximally from the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula and the coracoid process via a long tendon, providing a stable base, and inserts distally onto the radial tuberosity of the radius through another tendon, enabling forearm flexion and supination.[24] This proximal-to-distal arrangement underscores how origins often span multiple points for broader stability, whereas insertions may be more concentrated for precise movement. The terminology traces its roots to Latin, with "origin" derived from oriri, meaning "to rise" or "arise," reflecting the stable, foundational role of this attachment in initiating motion.[25] "Insertion," from inserere meaning "to put in," highlights the integration of the muscle into the moving structure.Intrinsic and Extrinsic Muscles

In anatomy, muscles are classified as intrinsic or extrinsic based on their positional relationship to the specific body region or organ they act upon. Intrinsic muscles originate and insert entirely within that region, enabling fine movements of its internal parts without displacing the region as a whole.[26] Extrinsic muscles, by contrast, originate outside the region—often from a more proximal structure—and insert into it, allowing for coarser, more powerful movements that reposition the entire region.[26] This distinction is particularly useful in regional anatomy for describing functional specialization and is commonly applied to structures like the limbs, tongue, eye, and larynx.[27] In the limbs, the classification highlights compartmental organization and functional roles. For instance, the intrinsic muscles of the hand, such as the interossei, arise from the metacarpal bones and act to abduct or adduct the fingers, facilitating precise grip and dexterity.[26] These contrast with extrinsic hand muscles, like the flexor digitorum profundus originating from the ulna in the forearm, which flex the distal phalanges with greater force but less finesse.[26] Similar patterns occur in the foot, where intrinsic muscles like the lumbricals enable toe adjustments, while extrinsic ones from the leg, such as the fibularis longus, perform foot eversion.[28] Compartmental terms, such as the anterior and posterior compartments of the leg, further refine this by grouping muscles based on fascial divisions, though the intrinsic-extrinsic divide emphasizes regional boundaries over compartments alone.[28] For the tongue, intrinsic muscles form a fibrous network within the organ itself, altering its shape for speech and mastication—examples include the superior and inferior longitudinal muscles, which shorten or elongate the tongue.[29] Extrinsic tongue muscles, originating from nearby bones like the mandible (genioglossus) or hyoid (hyoglossus), protrude or retract the tongue as a unit.[29] In the eye, the extrinsic muscles—collectively termed extraocular muscles—originate from the orbital walls and insert onto the sclera of the eyeball, enabling coordinated gaze shifts; there are no true skeletal intrinsic muscles within the eyeball, though intraocular smooth muscles like the ciliary adjust focus.[30] The larynx exemplifies this classification in the neck, where intrinsic muscles, such as the cricothyroid and posterior cricoarytenoid, lie wholly within the laryngeal framework to adjust vocal fold tension and position for phonation.[31] Extrinsic laryngeal muscles, including the thyrohyoid and sternothyroid, arise from the hyoid or sternum and elevate or depress the larynx during swallowing or respiration.[31] This terminology aids surgical planning, such as in laryngectomies, by clarifying which muscles affect internal laryngeal dynamics versus whole-organ mobility.[31] Not all muscles fit this binary neatly; some, like certain back muscles, exhibit hybrid characteristics with partial origins outside their primary region, blending intrinsic shaping with extrinsic positioning.[32]Muscle Architecture

Muscle architecture refers to the arrangement of muscle fibers within a muscle relative to its axis of force generation, which fundamentally influences the muscle's mechanical properties such as force production and excursion length.[33] This internal organization varies across muscles to optimize function for specific biomechanical demands. Fusiform muscles feature spindle-shaped structures with fibers oriented parallel to the muscle's long axis, allowing for greater shortening velocity and range of motion.[34] A representative example is the biceps brachii, which facilitates rapid elbow flexion.[35] In contrast, pennate muscles exhibit a feather-like pattern where fibers attach obliquely to a central tendon, enabling higher force generation through more fibers acting in parallel despite shorter individual fiber lengths.[36] The gastrocnemius, a bipennate pennate muscle, exemplifies this by producing substantial power for plantarflexion during locomotion.[37] Pennate muscles are classified into subtypes based on fiber arrangement: unipennate, with fibers inserting on one side of the tendon (e.g., extensor digitorum longus); bipennate, with fibers on both sides (e.g., rectus femoris); and multipennate, featuring multiple layers of obliquely arranged fibers (e.g., deltoid).[38][36] Additionally, fan-shaped (radiate) muscles converge from a broad origin to a narrow insertion, as seen in the pectoralis major, while triangular muscles like the deltoid combine multipennate features with a wedge-like form to distribute force across the shoulder.[39] A key metric in assessing muscle architecture is the physiologic cross-sectional area (PCSA), which estimates maximum force capacity by accounting for the effective number of fibers in parallel; it is calculated as PCSA = (muscle volume / fiber length) × shape factor, where the shape factor adjusts for pennation angle in non-parallel arrangements.[40] Functionally, pennate architectures enhance force output at the cost of reduced shortening distance and velocity, whereas parallel fusiform designs prioritize excursion and speed over peak force.[35] In evolutionary terms, muscle architecture has adapted across animal lineages to improve locomotion efficiency, with pennate patterns converging in species requiring high-force propulsion, such as snakes navigating diverse terrains, and fusiform traits favoring agile movements in vertebrates like primates.[42][43] These variations reflect selective pressures for balancing force-velocity trade-offs in specific ecological niches.[44]Muscle Components

Muscle Fibers

Muscle fibers, also known as myofibers, are the fundamental contractile units of skeletal muscle, consisting of elongated, cylindrical, multinucleated cells that form through the fusion of myoblasts during development, resulting in syncytial structures with diameters typically ranging from 10 to 100 micrometers and lengths spanning many centimeters.[45][46] These cells are enveloped by a plasma membrane called the sarcolemma, which encloses the sarcoplasm—the specialized cytoplasm containing organelles, glycogen, and mitochondria—and houses numerous myofibrils that impart the characteristic striated appearance.[8] Each myofibril is composed of repeating sarcomeres, the basic functional units of contraction, defined as the segment from one Z-line (or Z-disc) to the next, where thin actin filaments anchor at the Z-lines and interdigitate with thick myosin filaments in the central region.[47] The sarcomere's structure includes the anisotropic A band, corresponding to the full length of the myosin filaments; the isotropic I band, spanning the actin filaments between adjacent sarcomeres; and the H zone within the A band, a lighter region containing only myosin tails devoid of actin overlap during rest.[48][49] Skeletal muscle fibers are classified into distinct types based on their myosin heavy chain isoforms, contractile speed, and metabolic properties, primarily Type I, Type IIa, and Type IIx (in humans). Type I fibers, or slow oxidative fibers, express myosin heavy chain 7 (MYH7) and rely on aerobic metabolism for sustained, low-power contractions, making them fatigue-resistant and suited for endurance activities such as posture maintenance.[50][51] Type IIa fibers, or fast oxidative-glycolytic fibers, express myosin heavy chain 2 (MYH2) and combine oxidative and glycolytic pathways for versatile, moderate-force contractions with good fatigue resistance, supporting activities like moderate-intensity exercise.[52] Type IIx fibers, expressing myosin heavy chain 1 (MYH1), are fast glycolytic fibers that generate high power through anaerobic metabolism but fatigue quickly, ideal for short bursts of intense effort such as sprinting.[50][51] These classifications reflect adaptations in mitochondrial density, capillary supply, and enzyme profiles, with fiber type distribution varying by muscle function—for instance, postural muscles like the soleus containing more Type I fibers.[52] Motor unit recruitment follows Henneman's size principle, whereby smaller motor units—typically innervating Type I fibers—are activated first to enable fine, precise control of low-force movements, with progressively larger units involving Type II fibers recruited as force demands increase for graded contraction.[53][54] This orderly progression ensures efficient force modulation without abrupt jumps in tension. At the histological level, excitation-contraction coupling is facilitated by transverse tubules (T-tubules), invaginations of the sarcolemma that propagate action potentials deep into the fiber, triggering calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum—a specialized endoplasmic reticulum forming terminal cisternae adjacent to T-tubules—via dihydropyridine and ryanodine receptors, ultimately enabling actin-myosin cross-bridge cycling.[55][56]Muscle Slips

Muscle slips refer to discrete bundles or heads of a muscle that possess independent origins or insertions, forming subdivisions within a larger muscle structure. These slips are composed of muscle fibers that converge or diverge to facilitate specialized attachments, distinguishing them from the histological details of individual fibers.[57][58] Anatomically, each slip typically maintains its own origin and insertion points while sharing a common innervation with the parent muscle, enabling coordinated yet potentially differential function. For instance, the pectoralis minor muscle originates via three distinct slips from the anterior surfaces of the third, fourth, and fifth ribs near their costal cartilages, converging to insert on the coracoid process of the scapula; all slips are innervated by the medial pectoral nerve (C8-T1).[59][60] This shared innervation ensures unified neural control despite separate attachments. The presence of muscle slips allows for differential activation of bundles, supporting fine-tuned and complex movements by permitting varied tension across the muscle. This arrangement is particularly prevalent in facial and masticatory muscles, where precise control is essential for expressions and jaw mechanics.[61][62] Key examples include the digastric muscle, characterized by two bellies (anterior and posterior slips) connected by an intermediate tendon, with the anterior belly originating from the digastric fossa of the mandible and the posterior from the mastoid notch of the temporal bone; with the anterior belly innervated by the mylohyoid nerve (a branch of the trigeminal nerve, CN V) and the posterior belly by the facial nerve (CN VII), but function via their distinct insertions on the hyoid bone. The multifidus muscle features multiple slips arising from transverse processes, mamillary processes, and articular facets of vertebrae, inserting into the spinous processes two to four segments superiorly, all innervated by the dorsal rami of spinal nerves for segmental spinal stabilization. Additionally, the temporalis muscle exhibits multiple slips with horizontal and vertical orientations that coalesce into a tendon inserting on the coronoid process of the mandible, enabling variations in jaw elevation; these slips are innervated by the deep temporal nerves (branches of the mandibular nerve).[63][64][65][66]Composite Muscles

Composite muscles are skeletal muscles composed of multiple anatomically and functionally distinct components, often referred to as heads or bellies, that collectively contribute to a primary action while allowing for nuanced variations in movement. These components typically arise from separate origins but converge toward a common insertion, enabling the muscle to perform versatile functions across different joints or ranges of motion.[67] Unlike simpler muscles, composite structures reflect evolutionary adaptations for complex biomechanical demands, such as in limb extension or flexion.[68] Key terms for these components include "heads," which denote the primary divisions (e.g., long, lateral, and medial heads), and "bellies," emphasizing the fleshy, contractile portions of each segment. For instance, the triceps brachii features three heads originating from the scapula and humerus, each with distinct fiber orientations that enhance elbow extension efficiency.[69] Similarly, muscle slips may represent smaller subdivisions within these heads, further refining the muscle's architecture.[70] The functional advantage of composite muscles lies in their ability to generate coordinated yet independent actions; for example, in the quadriceps femoris, the four heads—rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius—extend the knee, but the rectus femoris additionally flexes the hip due to its biarticular span.[71] This modularity supports precise control in activities like walking or jumping, where selective activation of heads optimizes force distribution.[72] The flexor digitorum superficialis exemplifies this by dividing into four tendons that independently flex the proximal interphalangeal joints of the fingers, facilitating fine motor tasks such as grasping.[73] Innervation of composite muscles is generally provided by a single nerve to all components, promoting unified contraction, as seen in the quadriceps femoris and triceps brachii, both supplied by the femoral and radial nerves, respectively.[71][69] However, some exhibit dual innervation, where separate nerves target different heads, enhancing functional independence; the flexor digitorum profundus, for instance, receives input from both the ulnar and anterior interosseous nerves, allowing differential control of finger flexion.[74] The iliopsoas, formed by the psoas major and iliacus, shares innervation from lumbar plexus branches (L1-L3) but demonstrates slight variations in fiber-specific supply.[68]Functional Roles in Movement

Agonists and Antagonists

In skeletal muscle anatomy, an agonist, also known as the prime mover, is the primary muscle responsible for initiating and executing a specific movement by contracting to produce the desired action at a joint.[75] For instance, the biceps brachii serves as the agonist during elbow flexion, shortening to bend the forearm toward the shoulder.[19] The prime mover term specifically denotes the main agonist that generates the majority of force for the motion, distinguishing it from supporting muscles.[76] An antagonist is the muscle that opposes the action of the agonist, typically relaxing or lengthening to allow the movement to occur while preventing overextension or uncontrolled motion.[77] In the example of elbow flexion, the triceps brachii acts as the antagonist to the biceps brachii, extending the elbow when active but inhibiting its own contraction to facilitate flexion.[78] Antagonistic pairs consist of muscles positioned on opposite sides of a joint that perform reciprocal actions, such as flexors and extensors, enabling bidirectional movement across the joint.[79] A fixator is a muscle that stabilizes the origin of the prime mover or the joint itself, ensuring efficient action without unwanted displacement.[75] The coordination between agonists and antagonists is facilitated by reciprocal inhibition, a spinal reflex mechanism where activation of the agonist inhibits the antagonist via interneurons, promoting smooth and controlled movement.[80] This process occurs through Ia afferent fibers from muscle spindles, which excite the agonist's motor neurons while suppressing the antagonist's, as seen in stretch reflexes.[81] The direction of muscle action in these pairs is determined by the relative positions of origin and insertion attachments on the bone.[82]Synergists and Fixators

In skeletal muscle anatomy, synergists are muscles that assist the primary mover, or agonist, by contributing to the same joint action, thereby enhancing the efficiency and force of the movement.[76] For instance, during elbow flexion, the brachialis acts as a synergist to the biceps brachii by providing additional flexion force, particularly when the forearm is in a neutral position.[83] Fixators represent a specialized category of synergists that stabilize the origin of the agonist muscle, preventing displacement of the bone and allowing focused action at the intended joint.[75] An example is the rhomboid muscles, which fix the scapula against the thoracic wall during arm elevation, enabling effective contraction of the deltoid without scapular winging.[84] Key physiological terms associated with these roles include co-activation, where synergists contract simultaneously with the agonist to increase joint stability and force output.[85] Additionally, synergists can be classified as spurt or shunt muscles based on their mechanical effect: spurt muscles have insertions farther from the joint axis, promoting greater rotational movement, while shunt muscles insert closer to the joint, emphasizing stabilization over excursion.[86] These distinctions optimize multi-joint coordination, such as in shoulder abduction where the supraspinatus serves as an initial synergist to the deltoid, initiating the first 15-30 degrees of motion before the deltoid dominates.[87] The primary role of synergists and fixators is to refine movement precision by countering potential deviations, which is crucial in compound actions involving multiple joints.[75] Without fixators, proximal joints might shift, reducing the agonist's effectiveness; for example, in overhead reaching, rhomboids and trapezius co-activate to anchor the scapula, preventing compensatory tilting.[88] This supportive function is especially vital in dynamic activities, where uncontrolled motion could lead to inefficiency or injury.[89] At the physiological level, synergists often share neural innervation to facilitate synchronized activation, ensuring coordinated motor output from spinal motor neuron pools.[90] Studies using cross-correlation analysis have demonstrated direct shared inputs to motoneurons innervating synergist elbow flexors like the biceps brachii and brachioradialis, promoting precise timing during flexion tasks.[90] This neural coupling enhances overall movement economy by minimizing antagonistic interference and maximizing force transmission across joints.[91]Neutralizers

Neutralizers are a specialized subtype of synergist muscles that counteract unintended secondary actions during a primary movement, thereby ensuring precision and preventing deviations such as unwanted rotations or translations. This function is crucial in multi-joint or multi-planar motions where a prime mover might produce extraneous torques, allowing the intended action to occur without distortion. For instance, during scapular upward rotation (as in arm elevation), the lower trapezius acts as a neutralizer by counteracting the excessive elevatory pull of the upper trapezius, ensuring controlled motion.[92] Key terms associated with neutralizers include counteraction, which refers to the opposing of secondary torque generated by the agonist or other synergists, and multi-planar control, emphasizing the need to manage movements across multiple axes like flexion-extension, abduction-adduction, and rotation. These muscles enable fine-tuned coordination in complex activities, such as throwing or reaching, where uncontrolled secondary motions could lead to inefficiency or injury. The role of neutralizers is particularly evident in the upper extremity, where shoulder girdle muscles often require such balancing to isolate actions like pure abduction. Mechanistically, neutralizers typically contract isometrically, generating tension without significant length change to stabilize joints and neutralize opposing forces. This isometric activation provides a stable platform for the primary movers, minimizing energy waste and enhancing movement accuracy. In electromyographic studies, neutralizer activity peaks during the initial phases of multi-planar tasks, confirming their role in early counteraction. Examples illustrate this function clearly: during shoulder abduction by the middle deltoid, the posterior deltoid serves as a neutralizer by counteracting the internal rotation tendency of the anterior deltoid, promoting a neutral humeral rotation. Similarly, in forearm supination by the biceps brachii, the supinator muscle neutralizes any elbow flexion bias, isolating the rotational component. For example, during elbow extension by the triceps brachii, shoulder flexors such as the anterior deltoid act as neutralizers to prevent unwanted shoulder extension caused by the long head of the triceps.[93] These instances highlight how neutralizers contribute to isolated, efficient motions. Neutralizers often involve specific parts of composite muscles, where different fascicles or heads perform distinct roles—one as a neutralizer while another acts in synergy or primary movement. This relation underscores the adaptability of composite muscles in fulfilling neutralizing duties without dedicated single-muscle interventions. As a subset of synergists, neutralizers refine overall muscular cooperation by focusing on deviation prevention.Muscle Naming Conventions

Principles of Nomenclature

The nomenclature of muscles is fundamentally based on Latin and Greek roots, which provide a systematic framework for describing anatomical structures through etymological precision. These roots derive from classical languages used by early anatomists to convey essential characteristics, ensuring universality and clarity in scientific communication. Common criteria for naming include the muscle's location in the body (e.g., pectoralis indicating the chest region), shape (e.g., deltoid for a triangular form), relative size (e.g., magnus denoting large), number of origins or heads (e.g., biceps for two heads), primary action (e.g., flexor for bending), and points of attachment (e.g., sternocleidomastoid combining sternum, clavicle, and mastoid process). This descriptive approach prioritizes functional and morphological attributes, facilitating identification and understanding across disciplines. The historical development of muscle nomenclature traces back to the 16th century, when Andreas Vesalius, in his seminal work De humani corporis fabrica (1543), introduced Latin terms for skeletal muscles, drawing on Greek influences from predecessors like Galen while correcting earlier inaccuracies through direct dissection. Subsequent anatomists, such as Jean Riolan and Bernhard Siegfried Albinus, refined these terms in the 17th and 18th centuries, stabilizing many names amid proliferating synonyms. Formal standardization began in the late 19th century with the Basiliensia Nomina Anatomica (1895), which reduced thousands of variant terms to a cohesive list, followed by revisions like the Nomina Anatomica editions (1961–1989). The modern standard, Terminologia Anatomica (TA), was established in 1998 by the Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology under the International Federation of Associations of Anatomists (IFAA), encompassing 7,635 terms; it was updated in the second edition (2019) by the Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminologies (FIPAT) to incorporate advances and ensure consistency. Core rules of muscle nomenclature emphasize descriptive terms over eponyms to promote objectivity and avoid personalization, with priority given to Latin or Greek descriptors that highlight inherent features rather than discoverers. Eponyms have been largely phased out since the 1955 Parisiensia Nomina Anatomica, appearing only in reference indices and not as official terms, reflecting a shift toward universal accessibility. Exceptions exist in informal or vernacular usage, where colloquial names like "abs" for the abdominal muscles persist in clinical and educational contexts for brevity, though they lack formal status in TA. This system comprehensively covers approximately 600 named skeletal muscles in the human body, providing a standardized lexicon for the voluntary musculature. In contrast, smooth and cardiac muscles, which are involuntary, receive more generalized descriptive nomenclature focused on location or function (e.g., detrusor for the bladder wall muscle), as their diffuse and specialized distributions preclude the detailed skeletal naming conventions.Common Naming Patterns and Examples

Muscle names often follow patterns based on location, indicating the region or bone association, such as the temporalis muscle, which is situated at the temple (from Latin tempus, meaning temple).[94] Shape-based names describe the muscle's form, exemplified by the trapezius, which resembles a trapezoid when viewed from above.[94] Action-oriented names reflect primary function, like the adductor longus, which adducts the thigh toward the body's midline (from Latin ad, toward, and ducere, to lead).[94] Names derived from origin and insertion points specify attachment sites, with the origin typically named first, as in the sternohyoid muscle, originating from the sternum and inserting on the hyoid bone.[94] A prominent example is the gastrocnemius, the prominent calf muscle, whose name derives from Greek gastēr (belly or stomach) and knēmē (leg), referring to its bulbous, belly-like appearance on the posterior lower leg.[95] Similarly, the rectus abdominis, a key abdominal muscle, combines Latin rectus (straight) and abdominis (of the abdomen), describing its vertical, straight alignment along the midline of the anterior abdominal wall.[96] Variations in naming account for structural complexities, such as composite muscles with multiple heads or slips. The quadriceps femoris, for instance, is a composite of four muscles (from Latin quadri, four, and caput, head) that extend the knee, collectively named for their unified action despite separate origins.[94] The serratus anterior features multiple slips or digitations attaching to the ribs, earning its name from Latin serrare (to saw) due to its serrated, saw-tooth edge along the lateral rib cage, with anterior denoting its frontal position.[97] In contemporary anatomical nomenclature, there is a shift toward descriptive terms over eponymous ones to enhance universality and precision, as endorsed by the Federative International Programme for Anatomical Terminology (FIPAT), which prioritizes Latin and Greek roots for muscles like popliteus (from Latin poples, ham or back of the knee) instead of outdated personal attributions.[98] Certain regional or cultural names persist outside formal Latin/Greek systems, such as "hamstrings" for the posterior thigh muscles (biceps femoris, semitendinosus, and semimembranosus), originating from historical butchery practices where these tendons were used to suspend pig hams for curing, evoking the bend behind the knee.[99]Muscle Physiological States

Hypertrophy

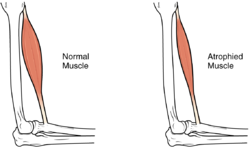

Muscle hypertrophy refers to the enlargement of skeletal muscle tissue, primarily through an increase in the cross-sectional area (CSA) of individual muscle fibers, resulting from enhanced protein synthesis that exceeds protein degradation. This adaptive response leads to greater muscle mass and strength, often observed in response to physiological stimuli.[100] The primary causes of muscle hypertrophy include resistance training, which imposes mechanical overload on muscles, and hormonal influences such as elevated levels of testosterone and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), which promote anabolic processes. Adequate nutrition, particularly sufficient protein and amino acid intake, supports this by providing substrates for protein synthesis and activating pathways like mTORC1. Key mechanisms involve mechanical tension as the dominant driver, sensed by mechanotransducers such as integrins and titin, leading to signaling cascades that enhance translation and ribosomal biogenesis; secondary contributors include metabolic stress from high-repetition training and micro-damage to muscle fibers that triggers repair and growth.[100][101][102] Hypertrophy manifests in two main subtypes: myofibrillar, characterized by increased contractile proteins like actin and myosin for enhanced force production, and sarcoplasmic, involving expansion of non-contractile elements such as glycogen and sarcoplasmic fluid for improved endurance. A critical process is myonuclear addition, where satellite cells—stem-like cells residing between the basal lamina and sarcolemma—proliferate, fuse with existing fibers, and donate nuclei to support transcriptional demands of enlarged fibers, thereby limiting hypertrophy potential without such fusion. In contrast to atrophy, which results in muscle wasting, hypertrophy represents net tissue growth.[100][101] Muscle hypertrophy is measured non-invasively using imaging techniques like ultrasound for real-time CSA assessment or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for precise volumetric analysis of muscle size; dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) provides whole-body composition estimates. Pathologically, hypertrophy in cardiac muscle, as seen in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, differs markedly from skeletal muscle adaptation, involving genetic mutations in sarcomere proteins leading to disorganized fibrosis and impaired function rather than beneficial growth.[100][102][103]Atrophy

Muscle atrophy refers to the progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength, resulting from an imbalance where protein degradation exceeds synthesis, leading to a reduction in the cross-sectional area of muscle fibers (myofibers).[104] Anatomically, this manifests as shrinkage of myofibrils, the contractile units within muscle cells, and eventual loss of organelles such as mitochondria, impairing the muscle's structural integrity and functional capacity.[104] The process is a normal physiological response in certain contexts but becomes pathological when excessive, affecting locomotion, metabolism, and overall homeostasis.[105] Atrophy is classified into three primary types based on etiology: physiologic (disuse), pathologic, and neurogenic. Physiologic atrophy, also termed disuse atrophy, occurs due to prolonged inactivity, such as bed rest or immobilization, where muscles are not subjected to mechanical loading; this type is typically reversible through exercise and nutrition, as seen in astronauts experiencing temporary muscle wasting during spaceflight.[106] Pathologic atrophy arises from systemic conditions like malnutrition, chronic diseases (e.g., cancer cachexia), or hormonal imbalances (e.g., excess glucocorticoids in Cushing's syndrome), involving accelerated protein breakdown and is often harder to reverse.[106] Neurogenic atrophy results from damage to motor neurons or their pathways, as in spinal muscular atrophy or peripheral nerve injuries, leading to denervation and rapid, selective wasting of affected muscle groups; this form is the most severe and least reversible due to the loss of neural innervation essential for muscle maintenance.[106][107] At the cellular level, muscle atrophy is driven by upregulated proteolytic systems that dismantle contractile proteins like actin and myosin. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) plays a central role, with E3 ligases such as atrogin-1/MAFbx and MuRF1 tagging proteins for degradation via 26S proteasomes, while the autophagy-lysosome pathway removes damaged organelles through macroautophagy and mitophagy.[104] These processes are regulated by signaling pathways, including the IGF-1/Akt pathway's inhibition and FoxO transcription factors' activation, which promote atrogenes (atrophy-related genes) in response to disuse, denervation, or inflammation.[104] In aging-related sarcopenia, a form of pathologic atrophy, cumulative factors like reduced anabolic signaling and increased oxidative stress contribute to progressive myofiber loss, particularly in type II fast-twitch fibers.[105] Clinically, atrophy presents with visible muscle wasting, weakness, and reduced range of motion, often diagnosed via imaging (e.g., MRI) or electromyography to assess fiber size and neural integrity.[107] Prevention emphasizes regular resistance training to maintain myofiber integrity, while treatment targets the underlying cause—such as physical therapy for disuse or electrical stimulation for neurogenic cases—to mitigate progression and restore function where possible.[106][107]References

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/[neuroscience](/page/Neuroscience)/fusiform-muscle