Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Superoxide dismutase [Cu-Zn] also known as superoxide dismutase 1 or hSod1 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the SOD1 gene, located on chromosome 21. SOD1 is one of three human superoxide dismutases.[5][6] It is implicated in apoptosis, familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Parkinson's disease.[6][7]

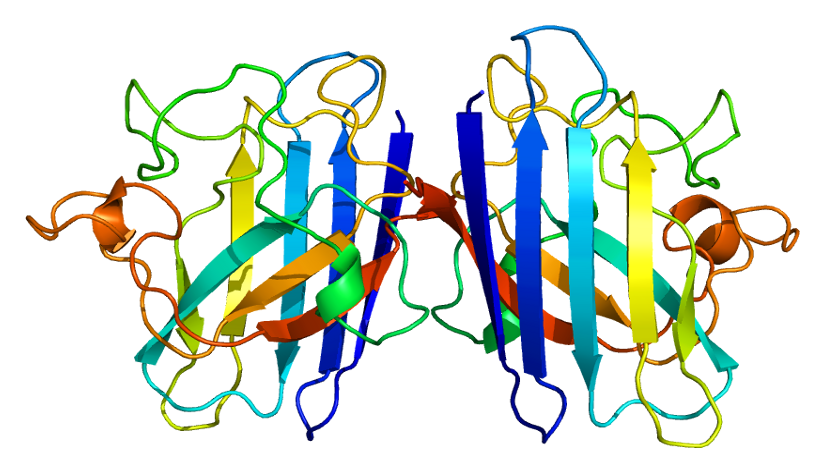

Structure

[edit]SOD1 is a 32 kDa homodimer which forms a beta barrel (β-barrel) and contains an intramolecular disulfide bond and a binuclear Cu/Zn site in each subunit. This Cu/Zn site holds the copper and a zinc ion and is responsible for catalyzing the disproportionation of superoxide to hydrogen peroxide and dioxygen.[8][9] The maturation process of this protein is complex and not fully understood, involving the selective binding of copper and zinc ions, formation of the intra-subunit disulfide bond between Cys-57 and Cys-146, and dimerization of the two subunits. The copper chaperone for Sod1 (CCS) facilitates copper insertion and disulfide oxidation. Although SOD1 is synthesized in the cytosol and can mature there, the fraction of expressed but still immature SOD1 that is targeted to the mitochondria must be inserted into the intermembrane space. There, it forms the disulfide bond, though not metalation, required for its maturation.[9] The mature protein is highly stable,[10] but unstable when in its metal-free and disulfide-reduced forms.[8][9][10] This manifests in vitro, as the loss of metal ions results in increased SOD1 aggregation, and in disease models, where low metalation is observed for insoluble SOD1. Moreover, the surface-exposed reduced cysteines could participate in disulfide crosslinking and, thus, aggregation.[8]

Function

[edit]SOD1 binds copper and zinc ions and is one of three superoxide dismutases responsible for destroying free superoxide radicals in the body. The encoded isozyme is a soluble cytoplasmic and mitochondrial intermembrane space protein, acting as a homodimer to convert naturally occurring, but harmful, superoxide radicals to molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide.[9][11] Hydrogen peroxide can then be broken down by another enzyme called catalase.

SOD1 has been postulated to localize to the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), where superoxide anions would be generated, or the intermembrane space. The exact mechanisms for its localization remains unknown, but its aggregation to the OMM has been attributed to its association with BCL-2. Wildtype SOD1 has demonstrated antiapoptotic properties in neural cultures, while mutant SOD1 has been observed to promote apoptosis in spinal cord mitochondria, but not in liver mitochondria, though it is equally expressed in both. Two models suggest SOD1 inhibits apoptosis by interacting with BCL-2 proteins or the mitochondria itself.[6]

Clinical significance

[edit]Role in oxidative stress

[edit]Most notably, SOD1 is pivotal in reactive oxygen species (ROS) release during oxidative stress by ischemia-reperfusion injury, specifically in the myocardium as part of a heart attack (also known as ischemic heart disease). Ischemic heart disease, which results from an occlusion of one of the major coronary arteries, is currently still the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in western society.[12][13] During ischemia reperfusion, ROS release substantially contribute to the cell damage and death via a direct effect on the cell as well as via apoptotic signals. SOD1 is known to have a capacity to limit the detrimental effects of ROS. As such, SOD1 is important for its cardioprotective effects.[14] In addition, SOD1 has been implicated in cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury, such as during ischemic preconditioning of the heart.[15] Although a large burst of ROS is known to lead to cell damage, a moderate release of ROS from the mitochondria, which occurs during nonlethal short episodes of ischemia, can play a significant triggering role in the signal transduction pathways of ischemic preconditioning leading to reduction of cell damage. It even has been observed that during this release of ROS, SOD1 plays an important role hereby regulating apoptotic signaling and cell death.

In one study, deletions in the gene were reported in two familial cases of keratoconus.[16] Mice lacking SOD1 have increased age-related muscle mass loss (sarcopenia), early development of cataracts, macular degeneration, thymic involution, hepatocellular carcinoma, and shortened lifespan.[17] Research suggests that increased SOD1 levels could be a biomarker for chronic heavy metal toxicity in women with long-term dental amalgam fillings.[18]

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig's disease)

[edit]Mutations (over 150 identified to date) in this gene have been linked to familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.[19][20][21] However, several pieces of evidence also show that wild-type SOD1, under conditions of cellular stress, is implicated in a significant fraction of sporadic ALS cases, which represent 90% of ALS patients.[22] The most frequent mutations are A4V (in the U.S.A.) and H46R (Japan). In Iceland only SOD1-G93S has been found. The most studied ALS mouse model is G93A. Rare transcript variants have been reported for this gene.[11]

Virtually all known ALS-causing SOD1 mutations act in a dominant fashion; a single mutant copy of the SOD1 gene is sufficient to cause the disease. The exact molecular mechanism (or mechanisms) by which SOD1 mutations cause disease are unknown. It appears to be some sort of toxic gain of function,[21] as many disease-associated SOD1 mutants (including G93A and A4V) retain enzymatic activity and Sod1 knockout mice do not develop ALS (although they do exhibit a strong age-dependent distal motor neuropathy).

ALS is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by selective loss of motor neurons causing muscle atrophy. The DNA oxidation product 8-OHdG is a well-established marker of oxidative DNA damage. 8-OHdG accumulates in the mitochondria of spinal motor neurons of persons with ALS.[23] In transgenic ALS mice harboring a mutant SOD1 gene, 8-OHdG also accumulates in mitochondrial DNA of spinal motor neurons.[24] These findings suggest that oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA of motor neurons due to altered SOD1 may be significant factor in the etiology of ALS.

A4V mutation

[edit]A4V (alanine at codon 4 changed to valine) is the most common ALS-causing mutation in the U.S. population, with approximately 50% of SOD1-ALS patients carrying the A4V mutation.[25][26][27] Approximately 10 percent of all U.S. familial ALS cases are caused by heterozygous A4V mutations in SOD1. The mutation is rarely if ever found outside the Americas.

It was recently estimated that the A4V mutation occurred 540 generations (~12,000 years) ago. The haplotype surrounding the mutation suggests that the A4V mutation arose in the Asian ancestors of Native Americans, who reached the Americas through the Bering Strait.[28]

The A4V mutant belongs to the WT-like mutants. Patients with A4V mutations exhibit variable age of onset, but uniformly very rapid disease course, with average survival after onset of 1.4 years (versus 3–5 years with other dominant SOD1 mutations, and in some cases such as H46R, considerably longer). This survival is considerably shorter than non-mutant SOD1 linked ALS.

H46R mutation

[edit]H46R (histidine at codon 46 changed to arginine) is the most common ALS-causing mutation in the Japanese population, with about 40% of Japanese SOD1-ALS patients carrying this mutation. H46R causes a profound loss of copper binding in the active site of SOD1, and as such, H46R is enzymatically inactive. The disease course of this mutation is extremely long, with the typical time from onset to death being over 15 years.[29] Mouse models with this mutation do not exhibit the classical mitochondrial vacuolation pathology seen in G93A and G37R ALS mice and unlike G93A mice, deficiency of the major mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme, SOD2, has no effect on their disease course.[29]

G93A mutation

[edit]G93A (glycine 93 changed to alanine) is a comparatively rare mutation, but has been studied very intensely as it was the first mutation to be modeled in mice. G93A is a pseudo-WT mutation that leaves the enzyme activity intact.[27] Because of the ready availability of the G93A mouse from Jackson Laboratory, many studies of potential drug targets and toxicity mechanisms have been carried out in this model. At least one private research institute (ALS Therapy Development Institute) is conducting large-scale drug screens exclusively in this mouse model. Whether findings are specific for G93A or applicable to all ALS-causing SOD1 mutations is at present unknown. It has been argued that certain pathological features of the G93A mouse are due to overexpression artifacts, specifically those relating to mitochondrial vacuolation (the G93A mouse commonly used from Jackson Lab has over 20 copies of the human SOD1 gene).[30] At least one study has found that certain features of pathology are idiosyncratic to G93A and not extrapolatable to all ALS-causing mutations.[29] Further studies have shown that the pathogenesis of the G93A and H46R models are clearly distinct; some drugs and genetic interventions that are highly beneficial/detrimental in one model have either the opposite or no effect in the other.[31][32][33]

Down syndrome

[edit]Down syndrome (DS) is usually caused by a triplication of chromosome 21. Oxidative stress is thought to be an important underlying factor in DS-related pathologies. The oxidative stress appears to be due to the triplication and increased expression of the SOD1 gene located in chromosome 21. Increased expression of SOD1 likely causes increased production of hydrogen peroxide leading to increased cellular injury.

The levels of 8-OHdG in the DNA of persons with DS, measured in saliva, were found to be significantly higher than in control groups.[34] 8-OHdG levels were also increased in the leukocytes of persons with DS compared to controls.[35] These findings suggest that oxidative DNA damage may lead to some of the clinical features of DS.

Interactions

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000142168 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022982 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Milani P, Gagliardi S, Cova E, Cereda C (2011). "SOD1 Transcriptional and Posttranscriptional Regulation and Its Potential Implications in ALS". Neurology Research International. 2011 458427. doi:10.1155/2011/458427. PMC 3096450. PMID 21603028.

- ^ a b c Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, Figlewicz DA, Sapp P, Hentati A, et al. (March 1993). "Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Nature. 362 (6415): 59–62. Bibcode:1993Natur.362...59R. doi:10.1038/362059a0. PMID 8446170. S2CID 265436.

- ^ Trist BG, Hilton JB, Hare DJ, Crouch PJ, Double KL (April 2021). "Superoxide Dismutase 1 in Health and Disease: How a Frontline Antioxidant Becomes Neurotoxic". Angewandte Chemie. 60 (17): 9215–9246. Bibcode:2021ACIE...60.9215T. doi:10.1002/anie.202000451. PMC 8247289. PMID 32144830.

- ^ a b c Estácio SG, Leal SS, Cristóvão JS, Faísca PF, Gomes CM (February 2015). "Calcium binding to gatekeeper residues flanking aggregation-prone segments underlies non-fibrillar amyloid traits in superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1)". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Proteins and Proteomics. 1854 (2): 118–126. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.11.005. PMID 25463043.

- ^ a b c d Sea K, Sohn SH, Durazo A, Sheng Y, Shaw BF, Cao X, et al. (January 2015). "Insights into the role of the unusual disulfide bond in copper-zinc superoxide dismutase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 290 (4): 2405–2418. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.588798. PMC 4303690. PMID 25433341.

- ^ a b Khare SD, Caplow M, Dokholyan NV (October 2004). "The rate and equilibrium constants for a multistep reaction sequence for the aggregation of superoxide dismutase in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (42): 15094–15099. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10115094K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0406650101. PMC 524068. PMID 15475574.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: SOD1 superoxide dismutase 1, soluble (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis 1 (adult))".

- ^ Murray CJ, Lopez AD (May 1997). "Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study". Lancet. 349 (9064): 1498–1504. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. PMID 9167458. S2CID 10556268.

- ^ Braunwald E, Kloner RA (November 1985). "Myocardial reperfusion: a double-edged sword?". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 76 (5): 1713–1719. doi:10.1172/JCI112160. PMC 424191. PMID 4056048.

- ^ Maslov LN, Naryzhnaia NV, Podoksenov I, Prokudina ES, Gorbunov AS, Zhang I, Peĭ Z (January 2015). "[Reactive oxygen species are triggers and mediators of an increase in cardiac tolerance to impact of ischemia-reperfusion]". Rossiiskii Fiziologicheskii Zhurnal imeni I.M. Sechenova. 101 (1): 3–24. PMID 25868322.

- ^ Liem DA, Honda HM, Zhang J, Woo D, Ping P (December 2007). "Past and present course of cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury". Journal of Applied Physiology. 103 (6): 2129–2136. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00383.2007. PMID 17673563. S2CID 24815784.

- ^ Udar N, Atilano SR, Brown DJ, Holguin B, Small K, Nesburn AB, Kenney MC (August 2006). "SOD1: a candidate gene for keratoconus". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 47 (8): 3345–3351. doi:10.1167/iovs.05-1500. PMID 16877401.

- ^ Muller FL, Lustgarten MS, Jang Y, Richardson A, Van Remmen H (August 2007). "Trends in oxidative aging theories". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 43 (4): 477–503. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.034. PMID 17640558.

- ^ Cabaña-Muñoz ME, Parmigiani-Izquierdo JM, Bravo-González LA, Kyung HM, Merino JJ (June 2015). "Increased Zn/Glutathione Levels and Higher Superoxide Dismutase-1 Activity as Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Women with Long-Term Dental Amalgam Fillings: Correlation between Mercury/Aluminium Levels (in Hair) and Antioxidant Systems in Plasma". PLOS ONE. 10 (6) e0126339. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1026339C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0126339. PMC 4468144. PMID 26076368.

- ^ Conwit RA (December 2006). "Preventing familial ALS: a clinical trial may be feasible but is an efficacy trial warranted?". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 251 (1–2): 1–2. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2006.07.009. PMID 17070848. S2CID 33105812.

- ^ Al-Chalabi A, Leigh PN (August 2000). "Recent advances in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Current Opinion in Neurology. 13 (4): 397–405. doi:10.1097/00019052-200008000-00006. PMID 10970056. S2CID 21577500.

- ^ a b Redler RL, Dokholyan NV (2012-01-01). "The complex molecular biology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)". Molecular Biology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. Vol. 107. pp. 215–62. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385883-2.00002-3. ISBN 978-0-12-385883-2. PMC 3605887. PMID 22482452.

- ^ Gagliardi S, Cova E, Davin A, Guareschi S, Abel K, Alvisi E, et al. (August 2010). "SOD1 mRNA expression in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Neurobiology of Disease. 39 (2): 198–203. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2010.04.008. PMID 20399857. S2CID 207065284.

- ^ Kikuchi H, Furuta A, Nishioka K, Suzuki SO, Nakabeppu Y, Iwaki T (April 2002). "Impairment of mitochondrial DNA repair enzymes against accumulation of 8-oxo-guanine in the spinal motor neurons of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Acta Neuropathologica. 103 (4): 408–414. doi:10.1007/s00401-001-0480-x. PMID 11904761. S2CID 2102463.

- ^ Warita H, Hayashi T, Murakami T, Manabe Y, Abe K (April 2001). "Oxidative damage to mitochondrial DNA in spinal motoneurons of transgenic ALS mice". Brain Research. Molecular Brain Research. 89 (1–2): 147–152. doi:10.1016/S0169-328X(01)00029-8. PMID 11311985.

- ^ Rosen DR, Bowling AC, Patterson D, Usdin TB, Sapp P, Mezey E, et al. (June 1994). "A frequent ala 4 to val superoxide dismutase-1 mutation is associated with a rapidly progressive familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Human Molecular Genetics. 3 (6): 981–987. doi:10.1093/hmg/3.6.981. PMID 7951249.

- ^ Cudkowicz ME, McKenna-Yasek D, Sapp PE, Chin W, Geller B, Hayden DL, et al. (February 1997). "Epidemiology of mutations in superoxide dismutase in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Annals of Neurology. 41 (2): 210–221. doi:10.1002/ana.410410212. PMID 9029070. S2CID 25595595.

- ^ a b Valentine JS, Hart PJ (April 2003). "Misfolded CuZnSOD and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (7): 3617–3622. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.3617V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0730423100. PMC 152971. PMID 12655070.

- ^ Broom WJ, Johnson DV, Auwarter KE, Iafrate AJ, Russ C, Al-Chalabi A, et al. (January 2008). "SOD1A4V-mediated ALS: absence of a closely linked modifier gene and origination in Asia". Neuroscience Letters. 430 (3): 241–245. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2007.11.004. PMID 18055113. S2CID 46282375.

- ^ a b c Muller FL, Liu Y, Jernigan A, Borchelt D, Richardson A, Van Remmen H (September 2008). "MnSOD deficiency has a differential effect on disease progression in two different ALS mutant mouse models". Muscle & Nerve. 38 (3): 1173–1183. doi:10.1002/mus.21049. PMID 18720509. S2CID 23971601.

- ^ Bergemalm D, Jonsson PA, Graffmo KS, Andersen PM, Brännström T, Rehnmark A, Marklund SL (April 2006). "Overloading of stable and exclusion of unstable human superoxide dismutase-1 variants in mitochondria of murine amyotrophic lateral sclerosis models". The Journal of Neuroscience. 26 (16): 4147–4154. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5461-05.2006. PMC 6673995. PMID 16624935.

- ^ Pan L, Yoshii Y, Otomo A, Ogawa H, Iwasaki Y, Shang HF, Hadano S (2012). "Different human copper-zinc superoxide dismutase mutants, SOD1G93A and SOD1H46R, exert distinct harmful effects on gross phenotype in mice". PLOS ONE. 7 (3) e33409. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...733409P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033409. PMC 3306410. PMID 22438926.

- ^ Bhattacharya A, Bokov A, Muller FL, Jernigan AL, Maslin K, Diaz V, et al. (August 2012). "Dietary restriction but not rapamycin extends disease onset and survival of the H46R/H48Q mouse model of ALS". Neurobiology of Aging. 33 (8): 1829–1832. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.002. PMID 21763036. S2CID 11227242.

- ^ Vargas MR, Johnson DA, Johnson JA (September 2011). "Decreased glutathione accelerates neurological deficit and mitochondrial pathology in familial ALS-linked hSOD1(G93A) mice model". Neurobiology of Disease. 43 (3): 543–551. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2011.04.025. PMC 3139005. PMID 21600285.

- ^ Komatsu T, Duckyoung Y, Ito A, Kurosawa K, Maehata Y, Kubodera T, et al. (September 2013). "Increased oxidative stress biomarkers in the saliva of Down syndrome patients". Archives of Oral Biology. 58 (9): 1246–1250. doi:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2013.03.017. PMID 23714170.

- ^ Pallardó FV, Degan P, d'Ischia M, Kelly FJ, Zatterale A, Calzone R, et al. (August 2006). "Multiple evidence for an early age pro-oxidant state in Down Syndrome patients". Biogerontology. 7 (4): 211–220. doi:10.1007/s10522-006-9002-5. PMID 16612664. S2CID 13657691.

- ^ Casareno RL, Waggoner D, Gitlin JD (September 1998). "The copper chaperone CCS directly interacts with copper/zinc superoxide dismutase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 273 (37): 23625–23628. doi:10.1074/jbc.273.37.23625. PMID 9726962.

- ^ Pasinelli P, Belford ME, Lennon N, Bacskai BJ, Hyman BT, Trotti D, Brown RH (July 2004). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated SOD1 mutant proteins bind and aggregate with Bcl-2 in spinal cord mitochondria". Neuron. 43 (1): 19–30. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.021. PMID 15233914. S2CID 18141051.

- ^ Cova E, Ghiroldi A, Guareschi S, Mazzini G, Gagliardi S, Davin A, et al. (October 2010). "G93A SOD1 alters cell cycle in a cellular model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis". Cellular Signalling. 22 (10): 1477–1484. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.05.016. PMID 20561900.

- ^ Cereda C, Cova E, Di Poto C, Galli A, Mazzini G, Corato M, Ceroni M (November 2006). "Effect of nitric oxide on lymphocytes from sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients: toxic or protective role?". Neurological Sciences. 27 (5): 312–316. doi:10.1007/s10072-006-0702-z. PMID 17122939. S2CID 25059353.

- ^ Cova E, Cereda C, Galli A, Curti D, Finotti C, Di Poto C, et al. (May 2006). "Modified expression of Bcl-2 and SOD1 proteins in lymphocytes from sporadic ALS patients". Neuroscience Letters. 399 (3): 186–190. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2006.01.057. PMID 16495003. S2CID 26076370.

Further reading

[edit]- de Belleroche J, Orrell R, King A (November 1995). "Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neurone disease (FALS): a review of current developments". Journal of Medical Genetics. 32 (11): 841–847. doi:10.1136/jmg.32.11.841. PMC 1051731. PMID 8592323.

- Ceroni M, Curti D, Alimonti D (2002). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and SOD1 gene: an overview". Functional Neurology. 16 (4 Suppl): 171–180. PMID 11996514.

- Zelko IN, Mariani TJ, Folz RJ (August 2002). "Superoxide dismutase multigene family: a comparison of the CuZn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2), and EC-SOD (SOD3) gene structures, evolution, and expression". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 33 (3): 337–349. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00905-X. PMID 12126755.

- Hadano S (June 2002). "[Causative genes for familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis]". Seikagaku. The Journal of Japanese Biochemical Society. 74 (6): 483–489. PMID 12138710.

- Noor R, Mittal S, Iqbal J (September 2002). "Superoxide dismutase--applications and relevance to human diseases". Medical Science Monitor. 8 (9): RA210 – RA215. PMID 12218958.

- Potter SZ, Valentine JS (April 2003). "The perplexing role of copper-zinc superoxide dismutase in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig's disease)". Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 8 (4): 373–380. doi:10.1007/s00775-003-0447-6. PMID 12644909. S2CID 22820101.

- Rotilio G, Aquilano K, Ciriolo MR (2004). "Interplay of Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase and nitric oxide synthase in neurodegenerative processes". IUBMB Life. 55 (10–11): 629–634. doi:10.1080/15216540310001628717. PMID 14711010. S2CID 19518719.

- Jafari-Schluep HF, Khoris J, Mayeux-Portas V, Hand C, Rouleau G, Camu W (January 2004). "[Superoxyde dismutase 1 gene abnormalities in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: phenotype/genotype correlations. The French experience and review of the literature]". Revue Neurologique. 160 (1): 44–50. doi:10.1016/S0035-3787(04)70846-2. PMID 14978393.

- Faraci FM, Didion SP (August 2004). "Vascular protection: superoxide dismutase isoforms in the vessel wall". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 24 (8): 1367–1373. doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000133604.20182.cf. PMID 15166009.

- Gagliardi S, Ogliari P, Davin A, Corato M, Cova E, Abel K, et al. (August 2011). "Flavin-containing monooxygenase mRNA levels are up-regulated in als brain areas in SOD1-mutant mice". Neurotoxicity Research. 20 (2): 150–158. doi:10.1007/s12640-010-9230-y. PMID 21082301. S2CID 21856030.

- Battistini S, Ricci C, Lotti EM, Benigni M, Gagliardi S, Zucco R, et al. (June 2010). "Severe familial ALS with a novel exon 4 mutation (L106F) in the SOD1 gene". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 293 (1–2): 112–115. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2010.03.009. PMID 20385392. S2CID 24895265.

112-115. sod 1

![2nnx: Crystal Structure of the H46R, H48Q double mutant of human [Cu-Zn] Superoxide Dismutase](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5f/PDB_2nnx_EBI.png/250px-PDB_2nnx_EBI.png)