Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Muscle cell

View on Wikipedia| Muscle cell | |

|---|---|

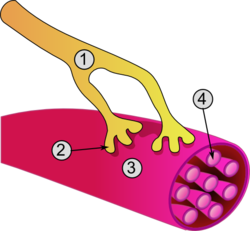

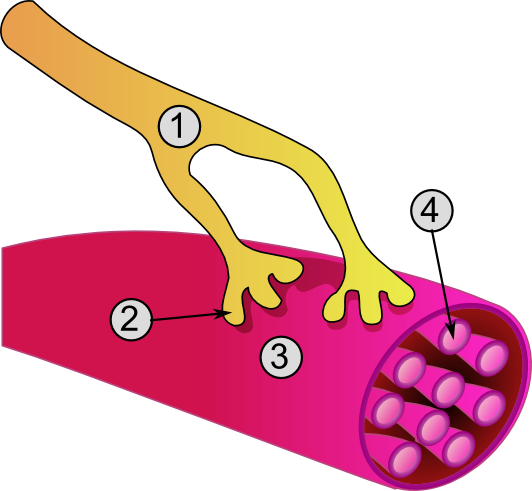

General structure of a skeletal muscle cell and neuromuscular junction: | |

| Details | |

| Location | Muscle |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | myocytus |

| MeSH | D032342 |

| TH | H2.00.05.0.00002 |

| FMA | 67328 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

A muscle cell, also known as a myocyte, is a mature contractile cell in the muscle of an animal.[1] In humans and other vertebrates there are three types: skeletal, smooth, and cardiac (cardiomyocytes).[2] A skeletal muscle cell is long and threadlike with many nuclei and is called a muscle fiber.[3] Muscle cells develop from embryonic precursor cells called myoblasts.[1]

Skeletal muscle cells form by fusion of myoblasts to produce multinucleated cells (syncytia) in a process known as myogenesis.[4][5] Skeletal muscle cells and cardiac muscle cells both contain myofibrils and sarcomeres and form a striated muscle tissue.[6]

Cardiac muscle cells form the cardiac muscle in the walls of the heart chambers, and have a single central nucleus.[7] Cardiac muscle cells are joined to neighboring cells by intercalated discs, and when joined in a visible unit they are described as a cardiac muscle fiber.[8]

Smooth muscle cells control involuntary movements such as the peristalsis contractions in the esophagus and stomach. Smooth muscle has no myofibrils or sarcomeres and is therefore non-striated. Smooth muscle cells have a single nucleus.

Structure

[edit]The unusual microscopic anatomy of a muscle cell gave rise to its terminology. The cytoplasm in a muscle cell is termed the sarcoplasm; the smooth endoplasmic reticulum of a muscle cell is termed the sarcoplasmic reticulum; and the cell membrane in a muscle cell is termed the sarcolemma.[9] The sarcolemma receives and conducts stimuli.

Skeletal muscle cells

[edit]

Skeletal muscle cells are the individual contractile cells within a muscle and are more usually known as muscle fibers because of their longer, threadlike appearance.[10] Broadly there are two types of muscle fiber performing in muscle contraction, either as slow twitch (type I) or fast twitch (type II).

A single muscle, such as the biceps brachii in a young adult human male, contains around 253,000 muscle fibers.[11] Skeletal muscle fibers are the only muscle cells that are multinucleated with the nuclei usually referred to as myonuclei. This occurs during myogenesis with the fusion of myoblasts, each contributing a nucleus to the newly formed muscle cell or myotube.[12] Fusion depends on muscle-specific proteins known as fusogens called myomaker and myomerger.[13]

A striated muscle fiber contains myofibrils consisting of long protein chains of myofilaments. There are three types of myofilaments: thin, thick, and elastic, that work together to produce a muscle contraction.[14] The thin myofilaments are filaments of mostly actin and the thick filaments are of mostly myosin, and they slide over each other to shorten the fiber length in a muscle contraction. The third type of myofilament is an elastic filament composed of titin, a very large protein.

In striations of muscle bands, myosin forms the dark filaments that make up the A band. Thin filaments of actin are the light filaments that make up the I band. The smallest contractile unit in the fiber is called the sarcomere, which is a repeating unit within two Z bands. The sarcoplasm also contains glycogen which provides energy to the cell during heightened exercise, and myoglobin, the red pigment that stores oxygen until needed for muscular activity.[14]

The sarcoplasmic reticulum, a specialized type of smooth endoplasmic reticulum, forms a network around each myofibril of the muscle fiber. This network is composed of groupings of two dilated end-sacs called terminal cisternae, and a single T-tubule (transverse tubule), which bores through the cell and emerge on the other side; together these three components form the triads that exist within the network of the sarcoplasmic reticulum, in which each T-tubule has two terminal cisternae on each side of it. The sarcoplasmic reticulum serves as a reservoir for calcium ions, so when an action potential spreads over the T-tubule, it signals the sarcoplasmic reticulum to release calcium ions from the gated membrane channels to stimulate muscle contraction.[14][15]

In skeletal muscle, at the end of each muscle fiber, the outer layer of the sarcolemma combines with tendon fibers at the myotendinous junction.[16][17] Within the muscle fiber pressed against the sarcolemma are multiply flattened nuclei; embryologically, this multinucleate condition results from multiple myoblasts fusing to produce each muscle fiber, where each myoblast contributes one nucleus.[14]

Cardiac muscle cells

[edit]The cell membrane of a cardiac muscle cell has several specialized regions, which may include the intercalated disc, and transverse tubules. The cell membrane is covered by a lamina coat which is approximately 50 nm wide. The laminar coat is separable into two layers; the lamina densa and lamina lucida. In between these two layers can be several different types of ions, including calcium.[18]

Cardiac muscle, like skeletal muscle, is also striated, and the cells contain myofibrils, myofilaments, and sarcomeres as the skeletal muscle cell. The cell membrane is anchored to the cell's cytoskeleton by anchor fibers that are approximately 10 nm wide. These are generally located at the Z lines so that they form grooves, and transverse tubules emanate. In cardiac myocytes, this forms a scalloped surface.[18]

The cytoskeleton is what the rest of the cell builds off of and has two primary purposes: the first is to stabilize the topography of the intracellular components, and the second is to help control the size and shape of the cell. While the first function is important for biochemical processes, the latter is crucial in defining the surface-to-volume ratio of the cell. This heavily influences the potential electrical properties of excitable cells. Additionally, deviation from the standard shape and size of the cell can have a negative prognostic impact.[18]

Smooth muscle cells

[edit]Smooth muscle cells are so-called because they have neither myofibrils nor sarcomeres and therefore no striations. They are found in the walls of hollow organs, including the stomach, intestines, bladder and uterus, in the walls of blood vessels, and in the tracts of the respiratory, urinary, and reproductive systems. In the eyes, the ciliary muscles dilate and contract the iris and alter the shape of the lens. In the skin, smooth muscle cells such as those of the arrector pili cause hair to stand erect in response to cold temperature or fear.[19]

Smooth muscle cells are spindle-shaped with wide middles and tapering ends. They have a single nucleus and range from 30 to 200 micrometers in length. This is thousands of times shorter than skeletal muscle fibers. The diameter of their cells is also much smaller, which removes the need for T-tubules found in striated muscle cells. Although smooth muscle cells lack sarcomeres and myofibrils, they do contain large amounts of the contractile proteins actin and myosin. Actin filaments are anchored by dense bodies (similar to the Z discs in sarcomeres) to the sarcolemma.[19]

Development

[edit]A myoblast is an embryonic precursor cell that differentiates to give rise to the different muscle cell types.[20] Differentiation is regulated by myogenic regulatory factors, including MyoD, Myf5, myogenin, and MRF4.[21] GATA4 and GATA6 also play a role in myocyte differentiation.[22]

Skeletal muscle fibers are made when myoblasts fuse together; muscle fibers therefore are cells with multiple nuclei, known as myonuclei, with each cell nucleus originating from a single myoblast. The fusion of myoblasts is specific to skeletal muscle, and not cardiac muscle or smooth muscle.

Myoblasts in skeletal muscle that do not form muscle fibers dedifferentiate back into myosatellite cells. These satellite cells remain adjacent to a skeletal muscle fiber, situated between the sarcolemma and the basement membrane[23] of the endomysium (the connective tissue investment that divides the muscle fascicles into individual fibers). To re-activate myogenesis, the satellite cells must be stimulated to differentiate into new fibers.

Myoblasts and their derivatives, including satellite cells, can now be generated in vitro through directed differentiation of pluripotent stem cells.[24]

Kindlin-2 plays a role in developmental elongation during myogenesis.[25]

Function

[edit]Muscle contraction in striated muscle

[edit]

Skeletal muscle contraction

[edit]When contracting, thin and thick filaments slide past each other by using adenosine triphosphate. This pulls the Z discs closer together in a process called the sliding filament mechanism. The contraction of all the sarcomeres results in the contraction of the whole muscle fiber. This contraction of the myocyte is triggered by the action potential over the cell membrane of the myocyte. The action potential uses transverse tubules to get from the surface to the interior of the myocyte, which is continuous within the cell membrane. Sarcoplasmic reticula are membranous bags that transverse tubules touch but remain separate from. These wrap themselves around each sarcomere and are filled with Ca2+.[26]

Excitation of a myocyte causes depolarization at its synapses, the neuromuscular junctions, which triggers an action potential. With a singular neuromuscular junction, each muscle fiber receives input from just one somatic efferent neuron. Action potential in a somatic efferent neuron causes the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine.[27]

When the acetylcholine is released, it diffuses across the synapse and binds to a receptor on the sarcolemma, a term unique to muscle cells that refers to the cell membrane. This initiates an impulse that travels across the sarcolemma.[28]

When the action potential reaches the sarcoplasmic reticulum, it triggers the release of Ca2+ from the Ca2+ channels. The Ca2+ flows from the sarcoplasmic reticulum into the sarcomere with both of its filaments. This causes the filaments to start sliding and the sarcomeres to become shorter. This requires a large amount of ATP, as it is used in both the attachment and release of every myosin head. Very quickly, Ca2+ is actively transported back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum, which blocks the interaction between the thin and thick filaments. This, in turn, causes the muscle cell to relax.[28]

There are four main types of muscle contraction: isometric, isotonic, eccentric, and concentric.[29] Isometric contractions are skeletal muscle contractions that do not cause movement of the muscle, and isotonic contractions are skeletal muscle contractions that do cause movement. Eccentric contraction is when a muscle moves under a load. Concentric contraction is when a muscle shortens and generates force.

Cardiac muscle contraction

[edit]Specialized cardiomyocytes in the sinoatrial node generate electrical impulses that control the heart rate. These electrical impulses coordinate contraction throughout the remaining heart muscle via the electrical conduction system of the heart. Sinoatrial node activity is modulated, in turn, by nerve fibers of both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. These systems act to increase and decrease, respectively, the rate of production of electrical impulses by the sinoatrial node.

Evolution

[edit]The evolutionary origin of muscle cells in animals is highly debated: One view is that muscle cells evolved once, and thus all muscle cells have a single common ancestor. Another view is that muscles cells evolved more than once, and any morphological or structural similarities are due to convergent evolution, and the development of shared genes that predate the evolution of muscle – even the mesoderm (the germ layer) that gives rise to muscle cells in vertebrates).

Schmid & Seipel (2005)[30] argue that the origin of muscle cells is a monophyletic trait that occurred concurrently with the development of the digestive and nervous systems of all animals, and that this origin can be traced to a single metazoan ancestor in which muscle cells are present. They argue that molecular and morphological similarities between the muscle cells in non-bilaterian Cnidaria and Ctenophora are similar enough to those of bilaterians that there would be one ancestor in metazoans from which muscle cells derive. In this case, Schmid & Seipel argue that the last common ancestor of Bilateria, Ctenophora and Cnidaria, was a triploblast (an organism having three germ layers), and that diploblasty, meaning an organism with two germ layers, evolved secondarily, because they observed the lack of mesoderm or muscle found in most cnidarians and ctenophores. By comparing the morphology of cnidarians and ctenophores to bilaterians, Schmid & Seipel were able to conclude that there were myoblast-like structures in the tentacles and gut of some species of cnidarians and the tentacles of ctenophores. Since this is a structure unique to muscle cells, these scientists determined, based on the data collected by their peers, that this is a marker for striated muscles similar to that observed in bilaterians. The authors also remark that the muscle cells found in cnidarians and ctenophores are often contested due to the origin of these muscle cells being the ectoderm rather than the mesoderm or mesendoderm.

The origin of true muscle cells is argued by other authors to be the endoderm portion of the mesoderm and the endoderm. However, Schmid & Seipel (2005)[30] counter skepticism about whether the muscle cells found in ctenophores and cnidarians are "true" muscle cells, by considering that cnidarians develop through a medusa stage and polyp stage. They note that in the hydrozoans' medusa stage, there is a layer of cells that separates from the distal side of the ectoderm, which forms the striated muscle cells in a way similar to that of the mesoderm; they call this third separated layer of cells the ectocodon. Schmid & Seipel argue that, even in bilaterians, not all muscle cells are derived from the mesendoderm: Their key examples are that in both the eye muscles of vertebrates and the muscles of spiralians, these cells derive from the ectodermal mesoderm, rather than the endodermal mesoderm. Furthermore, they argue that since myogenesis does occur in cnidarians with the help of the same molecular regulatory elements found in the specification of muscle cells in bilaterians, there is evidence for a single origin for striated muscle.[30]

In contrast to this argument for a single origin of muscle cells, Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. (2012)[31] argue that molecular markers such as the myosin II protein used to determine this single origin of striated muscle predate the formation of muscle cells. They use an example of the contractile elements present in the Porifera, or sponges, that do truly lack this striated muscle containing this protein. Furthermore, Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. present evidence for a polyphyletic origin of striated muscle cell development through their analysis of morphological and molecular markers that are present in bilaterians and absent in cnidarians, ctenophores, and bilaterians. Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. showed that the traditional morphological and regulatory markers such as actin, the ability to couple myosin side chains phosphorylation to higher concentrations of the positive concentrations of calcium, and other MyHC elements are present in all metazoans not just the organisms that have been shown to have muscle cells. Thus, the usage of any of these structural or regulatory elements in determining whether or not the muscle cells of the cnidarians and ctenophores are similar enough to the muscle cells of the bilaterians to confirm a single lineage is questionable according to Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. Furthermore, they explain that the orthologues of the Myc genes that have been used to hypothesize the origin of striated muscle occurred through a gene duplication event that predates the first true muscle cells (meaning striated muscle), and they show that the Myc genes are present in the sponges that have contractile elements but no true muscle cells. Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. also showed that the localization of this duplicated set of genes that serve both the function of facilitating the formation of striated muscle genes, and cell regulation and movement genes, was already separated into striated muscle and non-muscle MHC. This separation of the duplicated set of genes is shown through the localization of the striated much to the contractile vacuole in sponges, while the non-muscle much was more diffusely expressed during developmental cell shape and change. Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. found a similar pattern of localization in cnidarians, except with the cnidarian N. vectensis having this striated muscle marker present in the smooth muscle of the digestive tract. Thus, they argue that the pleisiomorphic trait of the separated orthologues of much cannot be used to determine the monophylogeny of muscle, and additionally argue that the presence of a striated muscle marker in the smooth muscle of this cnidarian shows a fundamentally different mechanism of muscle cell development and structure in cnidarians.[31]

Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. (2012)[31] further argue for multiple origins of striated muscle in the metazoans by explaining that a key set of genes used to form the troponin complex for muscle regulation and formation in bilaterians is missing from the cnidarians and ctenophores, and 47 structural and regulatory proteins observed, Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. were not able to find even on unique striated muscle cell protein that was expressed in both cnidarians and bilaterians. Furthermore, the Z-disc seemed to have evolved differently even within bilaterians, and there is a great deal of diversity of proteins developed even between this clade, showing a large degree of radiation for muscle cells. Through this divergence of the Z-disc, Steinmetz, Kraus, et al. argue that there are only four common protein components that were present in all bilaterians muscle ancestors and that of these for necessary Z-disc components only an actin protein that they have already argued is an uninformative marker through its pleisiomorphic state is present in cnidarians. Through further molecular marker testing, Steinmetz et al. observe that non-bilaterians lack many regulatory and structural components necessary for bilaterian muscle formation and do not find any unique set of proteins to both bilaterians and cnidarians and ctenophores that are not present in earlier, more primitive animals such as the sponges and amoebozoans. Through this analysis, the authors conclude that due to the lack of elements that bilaterian muscles are dependent on for structure and usage, non-bilaterian muscles must be of a different origin with a different set of regulatory and structural proteins.[31]

In another take on the argument, Andrikou & Arnone (2015)[32] use the newly available data on gene regulatory networks to look at how the hierarchy of genes and morphogens and another mechanism of tissue specification diverge and are similar among early deuterostomes and protostomes. By understanding not only what genes are present in all bilaterians but also the time and place of deployment of these genes, Andrikou & Arnone discuss a deeper understanding of the evolution of myogenesis.[32]

In their paper, Andrikou & Arnone (2015)[32] argue that to truly understand the evolution of muscle cells, the function of transcriptional regulators must be understood in the context of other external and internal interactions. Through their analysis, Andrikou & Arnone found that there were conserved orthologues of the gene regulatory network in both invertebrate bilaterians and cnidarians. They argue that having this common, general regulatory circuit allowed for a high degree of divergence from a single well-functioning network. Andrikou & Arnone found that the orthologues of genes found in vertebrates had been changed through different types of structural mutations in the invertebrate deuterostomes and protostomes, and they argue that these structural changes in the genes allowed for a large divergence of muscle function and muscle formation in these species. Andrikou & Arnone were able to recognize not only any difference due to mutation in the genes found in vertebrates and invertebrates, but also the integration of species-specific genes that could also cause divergence from the original gene regulatory network function. Thus, although a common muscle patterning system has been determined, they argue that this could be due to a more ancestral gene regulatory network being co-opted several times across lineages with additional genes and mutations causing very divergent development of muscles. Thus, it seems that the myogenic patterning framework may be an ancestral trait. However, Andrikou & Arnone explain that the basic muscle patterning structure must also be considered in combination with the cis regulatory elements present at different times during development. In contrast with the high level of gene family apparatuses structure, Andrikou and Arnone found that the cis-regulatory elements were not well conserved both in time and place in the network, which could show a large degree of divergence in the formation of muscle cells. Through this analysis, it seems that the myogenic GRN is an ancestral GRN with actual changes in myogenic function and structure possibly being linked to later co-opting of genes at different times and places.[32]

Evolutionarily, specialized forms of skeletal and cardiac muscles predated the divergence of the vertebrate/arthropod evolutionary line.[33] This indicates that these types of muscle developed in a common ancestor sometime before 700 million years ago (mya). Vertebrate smooth muscle was found to have evolved independently from the skeletal and cardiac muscle types.

Invertebrate muscle cell types

[edit]The properties used for distinguishing fast, intermediate, and slow muscle fibers can be different for invertebrate flight and jump muscles.[34] To further complicate this classification scheme, the mitochondrial content, and other morphological properties within a muscle fiber, can change in a tsetse fly with exercise and age.[35]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Myocytes at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ^ Brunet, Thibaut; et al. (2016). "The evolutionary origin of bilaterian smooth and striated myocytes". eLife. 5: 1. doi:10.7554/elife.19607. ISSN 2050-084X. PMC 5167519.

- ^ Saladin, Kenneth S. (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-07-122207-5.

- ^ Scott, W; Stevens, J; Binder-Macleod, SA (2001). "Human skeletal muscle fiber type classifications". Physical Therapy. 81 (11): 1810–1816. doi:10.1093/ptj/81.11.1810. PMID 11694174. Archived from the original on 13 February 2015.

- ^ "Does anyone know why skeletal muscle fibers have peripheral nuclei, but the cardiomyocytes not? What are the functional advantages?". Archived from the original on 19 September 2017.

- ^ Betts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H.; Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark; Desaix, Peter (6 March 2013). "Cardiac muscle tissue". Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ "Muscle tissues". Archived from the original on 13 October 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ "Atrial structure, fibers, and conduction" (PDF). Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ Saladin, Kenneth S. (2011). Human anatomy (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 244–246. ISBN 978-0-07-122207-5.

- ^ "Structure of Skeletal Muscle | SEER Training". training.seer.cancer.gov.

- ^ Klein, CS; Marsh, GD; Petrella, RJ; Rice, CL (July 2003). "Muscle fiber number in the biceps brachii muscle of young and old men". Muscle & Nerve. 28 (1): 62–8. doi:10.1002/mus.10386. PMID 12811774. S2CID 20508198.

- ^ Cho, CH; Lee, KJ; Lee, EH (August 2018). "With the greatest care, stromal interaction molecule (STIM) proteins verify what skeletal muscle is doing". BMB Reports. 51 (8): 378–387. doi:10.5483/bmbrep.2018.51.8.128. PMC 6130827. PMID 29898810.

- ^ Prasad, V; Millay, DP (8 May 2021). "Skeletal muscle fibers count on nuclear numbers for growth". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 119: 3–10. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2021.04.015. PMC 9070318. PMID 33972174. S2CID 234362466.

- ^ a b c d Saladin, K (2012). Anatomy & Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 403–405. ISBN 978-0-07-337825-1.

- ^ Sugi, Haruo; Abe, T; Kobayashi, T; Chaen, S; Ohnuki, Y; Saeki, Y; Sugiura, S; Guerrero-Hernandez, Agustin (2013). "Enhancement of force generated by individual myosin heads in skinned rabbit psoas muscle fibers at low ionic strength". PLOS ONE. 8 (5) e63658. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...863658S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063658. PMC 3655179. PMID 23691080.

- ^ Charvet, B; Ruggiero, F; Le Guellec, D (April 2012). "The development of the myotendinous junction. A review". Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. 2 (2): 53–63. PMC 3666507. PMID 23738275.

- ^ Bentzinger, CF; Wang, YX; Rudnicki, MA (1 February 2012). "Building muscle: molecular regulation of myogenesis". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 4 (2) a008342. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a008342. PMC 3281568. PMID 22300977.

- ^ a b c Ferrari, Roberto. "Healthy versus sick myocytes: metabolism, structure and function" (PDF). oxfordjournals.org/en. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ a b Betts, J. Gordon; Young, Kelly A.; Wise, James A.; Johnson, Eddie; Poe, Brandon; Kruse, Dean H.; Korol, Oksana; Johnson, Jody E.; Womble, Mark; Desaix, Peter (6 March 2013). "Smooth muscle". Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ page 395, Biology, Fifth Edition, Campbell, 1999

- ^ Perry R, Rudnick M (2000). "Molecular mechanisms regulating myogenic determination and differentiation". Front Biosci. 5: D750–67. doi:10.2741/Perry. PMID 10966875.

- ^ Zhao R, Watt AJ, Battle MA, Li J, Bandow BJ, Duncan SA (May 2008). "Loss of both GATA4 and GATA6 blocks cardiac myocyte differentiation and results in acardia in mice". Dev. Biol. 317 (2): 614–9. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.013. PMC 2423416. PMID 18400219.

- ^ Zammit, PS; Partridge, TA; Yablonka-Reuveni, Z (November 2006). "The skeletal muscle satellite cell: the stem cell that came in from the cold". Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 54 (11): 1177–91. doi:10.1369/jhc.6r6995.2006. PMID 16899758.

- ^ Chal J, Oginuma M, Al Tanoury Z, Gobert B, Sumara O, Hick A, Bousson F, Zidouni Y, Mursch C, Moncuquet P, Tassy O, Vincent S, Miyazaki A, Bera A, Garnier JM, Guevara G, Heston M, Kennedy L, Hayashi S, Drayton B, Cherrier T, Gayraud-Morel B, Gussoni E, Relaix F, Tajbakhsh S, Pourquié O (August 2015). "Differentiation of pluripotent stem cells to muscle fiber to model Duchenne muscular dystrophy". Nature Biotechnology. 33 (9): 962–9. doi:10.1038/nbt.3297. PMID 26237517. S2CID 21241434.

- ^ Dowling JJ, Vreede AP, Kim S, Golden J, Feldman EL (2008). "Kindlin-2 is required for myocyte elongation and is essential for myogenesis". BMC Cell Biol. 9: 36. doi:10.1186/1471-2121-9-36. PMC 2478659. PMID 18611274.

- ^ "Structure, and Function of Skeletal Muscles". courses.washington.edu. Archived from the original on 15 February 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ "Muscle Fiber Excitation". courses.washington.edu. University of Washington. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ a b Ziser, Stephen. "Muscle Cell Anatomy & Function" (PDF). www.austincc.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Gash, Matthew C.; Kandle, Patricia F.; Murray, Ian V.; Varacallo, Matthew (2024). "Physiology, Muscle Contraction". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- ^ a b c Seipel, Katja; Schmid, Volker (1 June 2005). "Evolution of striated muscle: Jellyfish and the origin of triploblasty". Developmental Biology. 282 (1): 14–26. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.03.032. PMID 15936326.

- ^ a b c d Steinmetz, Patrick R.H.; Kraus, Johanna E.M.; Larroux, Claire; Hammel, Jörg U.; Amon-Hassenzahl, Annette; Houliston, Evelyn; et al. (2012). "Independent evolution of striated muscles in cnidarians and bilaterians". Nature. 487 (7406): 231–234. Bibcode:2012Natur.487..231S. doi:10.1038/nature11180. PMC 3398149. PMID 22763458.

- ^ a b c d Andrikou, Carmen; Arnone, Maria Ina (1 May 2015). "Too many ways to make a muscle: Evolution of GRNs governing myogenesis". Zoologischer Anzeiger. Special Issue: Proceedings of the 3rd International Congress on Invertebrate Morphology. 256: 2–13. doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2015.03.005.

- ^ OOta, S.; Saitou, N. (1999). "Phylogenetic relationship of muscle tissues deduced from the superimposition of gene trees". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 16 (6): 856–867. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026170. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 10368962.

- ^ Hoyle, Graham (1983). "8. Muscle cell diversity". Muscles and Their Neural Control. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 293–299. ISBN 978-0-471-87709-7.

- ^ Anderson, M.; Finlayson, L.H. (1976). "The effect of exercise on the growth of mitochondria and myofibrils in the flight muscles of the Tsetse fly, Glossina morsitans". J. Morphol. 150 (2): 321–326. doi:10.1002/jmor.1051500205. S2CID 85719905.

External links

[edit] Media related to Myocytes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Myocytes at Wikimedia Commons- Structure of a Muscle Cell

Muscle cell

View on GrokipediaStructure and Classification

Skeletal muscle cells

Skeletal muscle cells, also known as muscle fibers or myofibers, are elongated, cylindrical, multinucleated cells that form the functional units of skeletal muscles responsible for voluntary movement. These fibers arise from the fusion of multiple myoblasts during development, resulting in syncytial structures that can extend up to 30 cm in length in certain muscles like the sartorius, with diameters ranging from 10 to 100 micrometers. The multiple nuclei within each fiber are characteristically located at the periphery, just beneath the sarcolemma, the plasma membrane of the muscle cell. This multinucleated organization supports the large size and extensive contractile apparatus of the fibers, enabling powerful and coordinated contractions for locomotion and posture maintenance.[2][4][5] A defining feature of skeletal muscle cells is their striated appearance, caused by the highly organized arrangement of sarcomeres—the repeating units of the contractile apparatus—aligned within myofibrils that run parallel to the fiber's long axis. Skeletal muscle fibers are classified into two main types based on their contractile and metabolic properties: Type I (slow-twitch) fibers, which are oxidative and fatigue-resistant, suited for endurance activities like sustained posture or long-distance running; and Type II (fast-twitch) fibers, which are primarily glycolytic and generate rapid, powerful contractions for short bursts of activity, such as sprinting or weightlifting. Type II fibers can be further subdivided into Type IIa (fast oxidative-glycolytic, with moderate endurance) and Type IIx (fast glycolytic, with high power but low fatigue resistance), allowing muscles to adapt to diverse functional demands. The striations and fiber type distribution contribute to the precise control of force and speed in voluntary movements, with sarcomere organization detailed further in discussions of contractile proteins.[2][6][7] Human skeletal muscles contain varying numbers of these fibers; for example, the biceps brachii typically has approximately 253,000 fibers in young adults, organized into motor units where each fiber is innervated by a single motor neuron at a specialized synapse called the neuromuscular junction. This junction ensures precise, all-or-none activation of fibers within a motor unit, facilitating graded force production through recruitment of multiple units for voluntary actions like arm flexion. Surrounding the fibers are layers of connective tissue that provide structural support and transmit contractile forces: the endomysium envelops individual fibers, the perimysium bundles fibers into fascicles, and the epimysium encases the entire muscle. Additionally, skeletal muscle fibers are associated with satellite cells—quiescent stem cells located between the basal lamina and sarcolemma—that play a crucial role in muscle maintenance and repair by proliferating and fusing with damaged fibers to restore function.[8][9][10][11]Cardiac muscle cells

Cardiac muscle cells, also known as cardiomyocytes, are specialized striated muscle cells that form the contractile tissue of the heart. These cells are typically branched and cylindrical, with lengths ranging from 50 to 100 micrometers and diameters of about 25 micrometers, allowing for efficient packing within the myocardial wall. Unlike skeletal muscle fibers, each cardiac muscle cell contains a single, centrally located nucleus, which facilitates coordinated gene expression across the interconnected network. The striated appearance arises from the organized arrangement of contractile proteins within the cells, enabling powerful and rhythmic contractions essential for heart function.[12][13][14] A defining feature of cardiac muscle cells is the presence of intercalated discs, which are specialized junctions located at the ends of the cells where they connect to adjacent cardiomyocytes. These discs include desmosomes and fascia adherens for mechanical coupling, providing structural integrity to withstand the repetitive stretching and contracting of the heart. Gap junctions within the intercalated discs allow for electrical coupling by permitting the direct passage of ions and small molecules between cells, ensuring synchronized depolarization across the myocardium. This dual mechanical and electrical connectivity transforms individual cells into a functional syncytium, critical for efficient propagation of action potentials.[15][16][17] Within cardiac muscle cells, myofibrils are composed of repeating sarcomeres, similar to those in skeletal muscle, which consist of overlapping actin and myosin filaments responsible for contraction. However, the excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac cells features unique arrangements of T-tubules and the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) optimized for rapid calcium handling. T-tubules in cardiac muscle are larger and positioned at the Z-lines of sarcomeres, forming dyads with the SR rather than the triads seen in skeletal muscle, which enhances calcium influx from extracellular sources and release from intracellular stores. The SR surrounds the myofibrils closely, storing and releasing calcium ions efficiently to trigger contractions, with additional calcium entering via L-type channels during each beat to sustain the process.[18][19][13] Certain cardiac muscle cells exhibit autorhythmicity, the intrinsic ability to generate spontaneous action potentials without external stimulation, a property most prominent in pacemaker cells of the sinoatrial node. These specialized cells, derived from the same lineage as contractile cardiomyocytes, possess unique ion channel expressions, such as funny currents (If) and T-type calcium channels, that drive slow depolarization during diastole, leading to rhythmic firing at rates of 60-100 beats per minute. This autorhythmic capability initiates the heartbeat and propagates through the intercalated disc network to coordinate ventricular contraction.[13][20]Smooth muscle cells

Smooth muscle cells are fusiform, or spindle-shaped, uninucleated structures that typically measure 30 to 200 micrometers in length and 3 to 10 micrometers in width.[21] These cells lack the organized sarcomeres found in striated muscle, resulting in a smooth, non-striated appearance under light microscopy.[22] Instead, their contractile apparatus consists of thin actin filaments and thicker myosin filaments arranged in an oblique, crisscrossing pattern throughout the sarcoplasm, enabling a more diffuse and flexible force generation.[23] The actin filaments insert into dense bodies, which are discrete, electron-dense protein aggregates scattered throughout the cytoplasm and along the plasma membrane, serving to anchor the filaments and transmit contractile forces across the cell.[22] Intermediate filaments, primarily composed of desmin, link these dense bodies to one another and to the cell membrane, forming a cytoskeletal network that enhances mechanical stability and efficient force propagation to adjacent cells and extracellular matrix.[23] Smooth muscle is categorized into single-unit and multi-unit types based on cellular organization and coordination. Single-unit smooth muscle features cells electrically coupled by gap junctions containing connexins, promoting coordinated, wave-like activity resembling a functional syncytium, as observed in the tunica media of the small intestine.[22] Multi-unit smooth muscle, by contrast, comprises discrete cells with independent neural innervation and no widespread gap junctions, allowing precise, individual control, such as in the pupillary constrictor muscle of the iris.[23] These cells are predominantly situated in the tunica media of blood vessel walls, the muscularis layers of the digestive tract, and the bronchial walls of airways, where their elongated form and attachments facilitate sustained circumferential tension.[22] The plasma membrane of smooth muscle cells contains numerous caveolae, flask-shaped invaginations rich in cholesterol and sphingolipids that cluster L-type voltage-gated calcium channels, supporting localized calcium handling essential for structural integrity during prolonged activity.[23]Development and Regeneration

Embryonic development

Muscle cells originate from distinct regions of the mesoderm during early embryogenesis. Skeletal muscle cells derive from the paraxial mesoderm, specifically the somites, which form along the neural tube, while cardiac muscle cells and most smooth muscle cells arise primarily from the splanchnic layer of the lateral plate mesoderm, with some smooth muscle cells deriving from neural crest and other mesodermal sources.[24][25][26] Progenitor cells from these mesodermal origins undergo migration and commitment to the myogenic lineage, primarily regulated by the paired box transcription factors Pax3 and Pax7. In skeletal muscle development, Pax3-expressing cells in the dermomyotome of somites migrate to sites of muscle formation, such as the limb buds, where Pax7 further specifies satellite cell precursors and myogenic progenitors. Pax3 plays a predominant role in early embryonic myogenesis, driving delamination and migration of myoblasts, whereas Pax7 is essential for fetal muscle growth and the establishment of a progenitor pool.[27][28] Differentiation of these myogenic progenitors into mature muscle cells is orchestrated by the myogenic regulatory factors (MRFs), a family of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors including Myf5, MyoD, myogenin, and MRF4. Myf5 and MyoD initiate commitment to the myogenic lineage by activating muscle-specific gene expression in proliferating myoblasts, while myogenin and MRF4 promote terminal differentiation and the withdrawal from the cell cycle. These factors function in a hierarchical and partially redundant manner, with Myf5 being the earliest expressed during somitogenesis to specify myoblasts.[29][30] In skeletal muscle, mononucleated myoblasts fuse to form multinucleated myotubes, a process critical for generating the syncytial structure of muscle fibers. This fusion occurs after MRF activation, involving cell adhesion molecules and cytoskeletal rearrangements to align and merge myoblasts. For cardiac muscle, cardioblasts from the splanchnic mesoderm coalesce bilaterally and fuse to form the primitive heart tube around the midline, establishing the linear structure that undergoes subsequent looping and chamber formation. Smooth muscle cells differentiate from mesenchymal progenitors primarily in the splanchnic mesoderm, with additional contributions from neural crest cells for certain vascular types; these progenitors respond to local inductive signals, such as epithelial-mesenchymal interactions and TGF-β signaling, to form contractile layers around developing organs and vessels without myoblast fusion.[31][32][33][26] In human embryos, somitogenesis begins during the third week post-fertilization, with the first somites appearing around day 20 and continuing until week 5, providing the initial pool of skeletal muscle progenitors. Myotube formation in skeletal muscle commences by weeks 7-8, marking the onset of primary myogenesis, while the primitive heart tube assembles by the end of week 3. These processes are modulated by signaling pathways such as Wnt and Notch, which refine progenitor specification; Wnt signaling promotes myogenic commitment in somitic cells, whereas Notch inhibits premature differentiation to maintain the progenitor state.[34][35][36][37]Postnatal growth and regeneration

Postnatal muscle growth primarily occurs through hypertrophy, where skeletal muscle fibers increase in size in response to mechanical stimuli such as resistance exercise. This process involves the addition of myofibrils and an expansion in their cross-sectional area, driven by signaling pathways activated by mechanical tension, metabolic stress, and muscle damage.[38] Hormones like insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and nutrients further support protein synthesis, leading to net muscle mass gains without significant hyperplasia in adults.[39] In contrast, atrophy—characterized by reduced myofibril number and size—arises from disuse, such as immobilization, or aging-related sarcopenia, involving upregulated proteolysis via the ubiquitin-proteasome system and impaired mitochondrial function.[40] Sarcopenia, affecting up to 50% of individuals over 80, accelerates muscle loss through chronic inflammation and anabolic resistance, diminishing force production.[41] Muscle regeneration in postnatal life relies heavily on satellite cells, quiescent stem cells marked by Pax7 expression that reside between the basal lamina and sarcolemma of muscle fibers. Upon injury, such as strains or trauma, these cells activate, proliferate as Pax7-positive myoblasts, and differentiate into myocytes that fuse with damaged fibers or form new myofibers, restoring structure and function.[42] This process is robust in skeletal muscle, enabling repair after acute damage through coordinated expression of myogenic regulatory factors like MyoD and myogenin.[43] Cardiac muscle, however, exhibits minimal regenerative capacity postnatally; injury typically leads to cardiomyocyte apoptosis and replacement by fibrotic scar tissue via fibroblast activation, impairing contractility due to the limited proliferation of terminally differentiated cardiomyocytes.[44] Smooth muscle regeneration is intermediate, often involving dedifferentiation and proliferation of existing cells rather than dedicated stem cells.[45] Recent advances in muscle regeneration target satellite cell limitations and genetic defects. Stem cell therapies, particularly using mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from bone marrow or adipose tissue, enhance skeletal muscle repair by secreting paracrine factors that promote satellite cell activation and reduce inflammation in models of injury and dystrophy.[46] Ongoing clinical trials as of 2025 indicate that MSCs can improve functional outcomes in muscular dystrophies through mechanisms supporting myoblast fusion and vascularization.[47] For Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), CRISPR-Cas9 editing of the dystrophin gene has progressed to phase I/II trials, where ex vivo editing of patient myoblasts restores dystrophin expression, with preclinical data indicating up to 60% functional protein recovery and reduced fibrosis in animal models.[48] A 2025 trial update reports safe delivery via AAV vectors, with initial human results showing modest dystrophin restoration in limb muscles.[49]Molecular Components

Contractile proteins and filaments

Muscle cells rely on specialized contractile proteins organized into filaments to generate force and enable contraction. The primary proteins include myosin and actin, which form thick and thin filaments, respectively, interacting via the cross-bridge cycle to produce mechanical work from ATP hydrolysis.[50] These filaments are arranged differently in striated (skeletal and cardiac) versus smooth muscle, influencing contractility across cell types.[51] Thick filaments consist of myosin II, a hexameric protein with two heavy chains and four light chains. Each heavy chain (~200-220 kDa) features a globular motor head with actin- and nucleotide-binding sites, a neck region serving as a lever arm, and a coiled-coil tail for filament assembly.[52] The light chains (essential and regulatory, ~15-20 kDa) stabilize the neck and modulate activity. Myosin II exhibits ATPase activity in its head domain, hydrolyzing ATP to ADP and inorganic phosphate, which powers conformational changes and force generation during the power stroke.[52] Isoforms vary by muscle type, with fast skeletal myosin showing higher ATPase rates (~30 s⁻¹) compared to slow cardiac (~5-6 s⁻¹), adapting to physiological demands like speed versus endurance.[52][50] Thin filaments are polymers of actin, associated with regulatory proteins tropomyosin and troponin in striated muscle. Actin exists as globular monomers (G-actin, ~42 kDa) that polymerize into double-helical filamentous structures (F-actin, ~7 nm diameter), forming the core of thin filaments anchored at Z-lines.[51] Tropomyosin, a coiled-coil dimer (~40 kDa), binds along F-actin, spanning seven actin subunits and sterically blocking myosin-binding sites in the relaxed state.[53] The troponin complex, comprising three subunits, regulates this interaction: troponin C (TnC, ~18 kDa) binds calcium ions to initiate contraction; troponin I (TnI, ~21 kDa) inhibits actin-myosin binding at low calcium by anchoring tropomyosin in a blocked position; and troponin T (TnT, ~31 kDa) links the complex to tropomyosin.[53] Calcium binding to TnC induces TnI release, pivoting tropomyosin to expose myosin sites.[53] In striated muscle, these filaments organize into sarcomeres, the basic contractile units (~2-3 μm long). Thin filaments anchor at Z-lines, defining sarcomere boundaries, and extend into the isotropic I-band before overlapping thick filaments in the anisotropic A-band. The A-band spans the full length of thick filaments, with the central H-zone (lacking thin filament overlap) flanked by regions of partial overlap.[54] Titin, a giant elastic protein (~3-4 MDa), spans from Z-line to M-line, aligning filaments and providing passive elasticity via its extensible I-band region (tandem immunoglobulin and PEVK domains), which generates restoring force (0-5 pN per molecule) to maintain sarcomere integrity during stretch.[54][55] Smooth muscle lacks sarcomeres, featuring a non-sarcomeric arrangement of actin-myosin filaments in dense bodies and oblique lattices for isotropic contraction. Regulatory proteins caldesmon and calponin modulate interactions: caldesmon (~87-93 kDa), an actin- and myosin-binding protein, cross-links filaments, inhibits ATPase activity, and maintains myosin spacing to balance force without calcium sensitization.[56][57] Calponin (~34 kDa), actin-associated, reduces shortening velocity and stabilizes filaments but does not directly regulate force or calcium sensitivity.[57] These adaptations support sustained, low-energy contractions in organs like blood vessels.[56] The cross-bridge cycle kinetics underpin force generation, where total force arises from the number of attached bridges , force per bridge , and displacement :This models collective myosin head contributions during ATP-driven cycling.[58] The length-tension relationship, describing how force varies with sarcomere length, follows Hill's equation for force-velocity dynamics:

where is force, is velocity, is maximum isometric force, and , are muscle-specific constants shaping the hyperbolic curve.[59] This equation reveals molecular insights into cross-bridge attachment rates and energy efficiency.[59]