Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nalgonda

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

Nalgonda is a city[4] and municipality in the Indian state of Telangana. It is the headquarters of the Nalgonda district, as well as the headquarters of the Nalgonda mandal in the Nalgonda revenue division.[5] It is located about 90 kilometres (56 mi) from the state capital Hyderabad.

Key Information

Etymology

[edit]In the past, Nalgonda was referred to as Nilagiri. During the medieval Bahamani kingdom, it was renamed Nalgunda.[6] The name was changed to "Nalgonda" for official uses during the rule of the later Nizam kings.

History

[edit]Paleolithic Age

[edit]There is archaeological evidence that Paleolithic people lived in the area that is now Nalgonda, fashioning tools and weapons out of stone. Some of these implements have been found in the Nalgonda area, similar to those discovered at the Sloan archaeological site in Arkansas.

Neolithic Age

[edit]Traces of Neolithic culture were found at Chota Yelupu, where sling stones and other contemporary objects were excavated. Evidence of Megalithic culture was also found via the discovery of innumerable burials at various places around Nalgonda.

The Mauryas and Satavahanas (230 BC – 218 BC)

[edit]The political history of the Nalgonda district commences with the Mauryas. During the reign of Ashoka the Great, the Mauryas maintained control over the Nalgonda region. Later, the Satavahanas, who ruled between 230 BC and 218 BC, took control of the area.

During this period, the region established trade contacts with the Roman Empire.

Ikshvakus (227 AD – 306 AD)

[edit]In 227 AD, the Ikshvaku dynasty took control of the region. During this period, members of various Saka tribes migrated to the area. Buddhism flourished during this time.

Invasion of Samudragupta

[edit]After the Ikshvakus, the Pallavas and Yadavas fought for supremacy over the region. However, after Samudragupta (c. 335 AD – c. 375 AD) invaded and conquered most of India, the area fell under the control of his Gupta Empire. The Empire fell in the 6th century.

The Chalukyas and Rashtrakutas

[edit]Starting in the 6th century, the Chalukya dynasty ruled the modern-day Nalgonda region, as well as much of southern and central India. A major portion of the Nalgonda area appears to have passed from the Chalukyas of Badami to the Rashtrakutas. However, the Rashtrakutas fell in 973, and power shifted to the Chalukyas of Kalyani. The Chalukyas continued to rule the area until the end of the 12th century.

Medieval period

[edit]During the medieval era, the Kakatiya dynasty took control of the region from the western Chalukyas. During the reign of Prataparudra II, in 1323, the kingdom was annexed to the Tughluq Empire.

When Muhammad bin Tughluq ruled (around 1324–1351), Musunuri chief Kapayanayaka ceded a part of Nalgonda to Ala-ud-din Hasan Bahman Shah of the Bahmani Sultanate. He annexed the region to the Bahmani Kingdom.

In 1455, Jalal Khan he declared himself king at Nalgonda, but this was short-lived. He was quickly defeated and the region brought back to the Bahmani Kingdom.

During the time of the Bahmani Sultan Shihabud-din Mahmun, Sultan Quli was appointed as tarafdar of the Telangana region (now the state of Telangana). Quli's son, Jamshid, took control of the region from his father. Later, Qutub Shahis took control of the region, and maintained it until 1687.

Modern period: Mughals and Asaf Jahis

[edit]Nizam-ul-Mulk (Asaf Jah I) defeated Mubasiz Khan at Shaker Khere in Berar and ruled the Deccan autonomously. This district, like the other districts of Telangana, was controlled by Asaf Jahis, and remained under their rule for nearly two hundred and twenty-five years.

Geography

[edit]Nalgonda is located at 17°03′00″N 79°16′00″E / 17.050°N 79.2667°E.[7] It has an average elevation of 420 metres (1,380 ft).

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Nalgonda (1991–2020, extremes 1975–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.5 (97.7) |

39.5 (103.1) |

43.5 (110.3) |

45.2 (113.4) |

47.0 (116.6) |

46.3 (115.3) |

39.8 (103.6) |

38.8 (101.8) |

38.7 (101.7) |

37.5 (99.5) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.0 (95.0) |

46.3 (115.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.9 (87.6) |

33.3 (91.9) |

36.9 (98.4) |

39.3 (102.7) |

41.3 (106.3) |

37.1 (98.8) |

34.0 (93.2) |

33.1 (91.6) |

33.4 (92.1) |

32.6 (90.7) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.4 (86.7) |

34.6 (94.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 17.6 (63.7) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.2 (77.4) |

24.8 (76.6) |

23.3 (73.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

17.9 (64.2) |

23.4 (74.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 10.0 (50.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

15.3 (59.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

20.6 (69.1) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

20.8 (69.4) |

19.8 (67.6) |

16.2 (61.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 9.2 (0.36) |

6.9 (0.27) |

5.3 (0.21) |

16.6 (0.65) |

39.0 (1.54) |

95.2 (3.75) |

140.7 (5.54) |

147.2 (5.80) |

168.9 (6.65) |

141.4 (5.57) |

30.1 (1.19) |

6.1 (0.24) |

806.5 (31.75) |

| Average rainy days | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 5.0 | 6.9 | 7.5 | 6.8 | 5.1 | 2.3 | 0.4 | 37.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 17:30 IST) | 47 | 45 | 41 | 38 | 36 | 50 | 61 | 64 | 67 | 64 | 59 | 53 | 51 |

| Source: India Meteorological Department[8][9][10] | |||||||||||||

Nalgonda has been ranked 2nd best “National Clean Air City” under (Category 3 population under 3 lakhs cities) in India according to 'Swachh Vayu Survekshan 2024 Results'[11]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 9,711 | — |

| 1941 | 12,674 | +30.5% |

| 1951 | 22,183 | +75.0% |

| 1961 | 24,383 | +9.9% |

| 1971 | 33,126 | +35.9% |

| 1981 | 62,458 | +88.5% |

| 1991 | 84,910 | +35.9% |

| 2001 | 110,286 | +29.9% |

| 2011 | 135,744 | +23.1% |

| Source: [12] | ||

As of 2011[update] census of India, Nalgonda had a population of 135,744; of which 67,971 are male and 67,773 are female. An average of 86.83% city population were literate; where 92.91% of them were male and 80.78% were female literates.[13]

Governance

[edit]The municipality of Nalgonda was categorized as a "Grade-III municipality" when it was first created in 1941. It is now a "Special Grade Municipality."

Nalgonda's jurisdictional area is spread over 105 km2 (41 sq mi).[14] Its population is distributed over an area of 123.54 km2 (47.70 sq mi), which includes residents of the municipality Nalgonda, the rural areas of Panagallu, Gollaguda, Cherlapalli, Arjalabhavi, Gandhamvarigudam, and Marriguda.[5]

Economy

[edit]Nalgonda is being developed as part of KTR mantra of 3-D, Digitise, Decarbonize and Decentralize. As such it has an IT Tower. [15][16][17]

Transport

[edit]

The city is connected to major cities and towns by means of road and railways. National and state highways that pass through the city are National Highway 565, State highway 2 and 18.[18] Also National Highway 65 (Hyderabad to Vijayawada) passes through Nalgonda District.

Road

[edit]TGSRTC operates buses from Nalgonda to various destinations in Telangana state.

Railway

[edit]Nalgonda railway station provides rail connectivity to the city. It is classified as a B–category station in Guntur railway division of the South Central Railway zone and is located on the Pagidipalli-Nallapadu section of the division.[19]

Air

[edit]The closest airport to the city is Rajiv Gandhi International Airport, which is 112 km away.

Attractions

[edit]

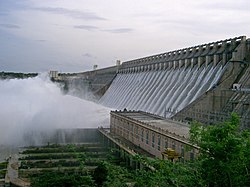

Nalgonda contains several religious sites, including Maruthi Mandir and Other attractions include the Nagarjuna Sagar Dam, a Gowthama Buddha Museum, and the Bhuvanangiri Fort, built by Tribhuvanamalla Vikramaditya VI, panagallu someswara temple and many masjid built by Alamgir in and around the district.[citation needed]

Education

[edit]As district headquarters, Nalgonda serves as a hub for primary and secondary education for surrounding villages. Nalgonda has many primary and upper primary schools, offering instruction in Telugu, Urdu, and English.[citation needed]

It also contains a number of colleges specializing in engineering, medicine, pharmacy, and sciences, as well as vocational colleges.[citation needed]

There are also many state government-operated schools and colleges in the city, such as Nagarjuna Government Degree college.[20]

- Kamineni Institute of Medical Sciences

- Mahatma Gandhi University, Nalgonda

- Government Medical College, Nalgonda

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Basic Information of Municipality". Official website of Nalgonda Municipality. Government of Telangana. Archived from the original on 8 November 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ "Elevation for Bhattiprolu". Velor outes. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ "District Codes". Government of Telangana Transport Department. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ^ "Cities having population 1 lakh and above, Census 2011" (PDF).

- ^ a b "District Census Handbook – Nalgonda" (PDF). Census of India. pp. 13–14, 40, 52. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ^ "Caste, Tribes". The castes and tribes of H.E.H. the Nizam's dominions by Siraj-ul-Hassan, Syed. Bombay : The Times Press. 1920.

- ^ "Nalgonda". fallingrain.com. Fallingrain. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ "Climatological Tables of Observatories in India 1991-2020" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ "Station: Nalgonda Climatological Table 1981–2010" (PDF). Climatological Normals 1981–2010. India Meteorological Department. January 2015. pp. 529–530. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Extremes of Temperature & Rainfall for Indian Stations (Up to 2012)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. December 2016. p. M14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Swachh Vayu Sarvekshan 2024" (PDF). Swachh Vayu Sarvekshan 2024. 7 September 2024.

- ^ "Census tables | Government of India". Archived from the original on 9 May 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2025.

- ^ "Nalgonda District Population Census 2011-2019, Andhra Pradesh literacy sex ratio and density". www.census2011.co.in. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ "Basic Information of Municipality". Municipal Administration & Urban Development Department. Government of Telangana. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ "KTR inaugurates Nizamabad's IT Tower, Nalgonda and Adilabad next". 9 August 2023.

- ^ "Telangana Nalgonda's 14-year-wait for IT Tower ends".

- ^ "KTR assures T-Hub and TASK centres in Nalgonda". 2 October 2023.

- ^ "Bus Stations". TSRTC. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ "Evolution of Guntur Division" (PDF). South Central Railway. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ^ "Nagarjuna Government College-NALGONDA". ngcnalgonda.org. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010.

External links

[edit]Nalgonda

View on GrokipediaNalgonda is a city and municipality in the Indian state of Telangana, serving as the administrative headquarters of Nalgonda district in the southern part of the state.[1] The name originates from the Telugu words nalla (black) and konda (hill), reflecting its historical association with local geography; it was previously known as Neelagiri under Rajput rule and later Nallagonda following the Bahmani conquest.[2] The district encompasses 7,122 square kilometers and has a history tied to medieval kingdoms, including the Padma Nayakas who controlled Deverakonda Fort from 1287 to 1482 AD, and the Kakatiyas who built Shiva temples in Panagal.[2][3] A defining feature is the Nagarjuna Sagar Dam, constructed between 1955 and 1967 and dedicated in 1972, which stands 124 meters high as one of the world's tallest masonry dams and creates the third-largest man-made lake globally.[2] Nalgonda's economy centers on agriculture, which supports approximately 75% of the population directly or indirectly, with key crops such as paddy and cotton cultivated across a net cropped area of 312,000 hectares, aided by irrigation from the Nagarjunasagar Left Canal and wells.[3] Industrial activities include 151 rice mills, 350 power looms for cotton, 14 pharmaceutical units, and other sectors like chemicals, stone crushing, and edible oil refining, complemented by service sectors such as trade and transport.[3]

Etymology

Name Origin and Historical References

The name Nalgonda is derived from the Telugu words nalla (black) and konda (hill), translating to "Black Hills," a reference to the dark-hued rocky terrain surrounding the area.[2][4] This etymology reflects the region's geological features, characterized by basalt and granite formations prevalent in the Deccan Plateau.[2] Historically, the area was known as Neelagiri (blue mountain) during the rule of Rajput chieftains, possibly alluding to the bluish tint of distant hills or atmospheric effects on the landscape.[2] Following the conquest by Bahmani Sultanate ruler Alauddin Bahman Shah in the 14th century, the name evolved to Nallagonda, incorporating the Telugu nalla to denote the black hills, before standardizing as Nalgonda in subsequent administrative records.[2] Early inscriptions, such as the Velmjala inscription dated 927 CE from the Rashtrakuta period, provide contextual evidence of regional governance but do not directly reference the modern place name, indicating that Neelagiri or precursor terms predated Telugu linguistic dominance in local nomenclature.[5] No verifiable ancient texts, such as Vedic or Sangam literature, explicitly mention Nalgonda by name, though the district's prehistoric and early historic sites suggest continuity of settlement under Mauryan and Satavahana influence from the 3rd century BCE, where toponymic shifts likely occurred with linguistic assimilation.[2] The transition from Nilagiri to Nalgonda underscores the impact of successive dynasties— from Rajputs to Bahmanis—on regional identity, with the current form solidified under later Deccan sultanates and Hyderabad state administration.[2]History

Prehistoric Settlements

Archaeological evidence indicates prehistoric human activity in Nalgonda district dating back to the Neolithic period, characterized by polished stone tools and early settled practices. A notable discovery includes a black basalt polished stone axe from Gundrampalli village in Chityal mandal, dated approximately 4,000 years old (circa 2000 BCE), suggesting agricultural communities with tool-making traditions reliant on local stone resources.[6][7] Rock art sites further attest to Neolithic habitation, with depictions of bulls, stags, dogs, human figures, and scenes of hunting such as a man combating a tiger found on a hillock near Ramalingalagudem village in Tipparthi mandal. These engravings, accompanied by grooves likely used for sharpening stone axes, reflect prehistoric lifestyles involving animal husbandry, hunting, and rudimentary craftsmanship during the Neolithic era (circa 6000–2000 BCE).[8][9] Mesolithic and Neolithic grooves have also been identified at Buddhavanam, a site along the Krishna River, indicating transitional tool use from hunter-gatherer to farming societies, with evidence of stone working predating metal ages.[10] Megalithic structures, including menhirs and a dolmen near Gudipalli mandal, point to late prehistoric Iron Age settlements (circa 1200–300 BCE), where communities erected burial monuments possibly linked to pastoral or warrior cultures, though these mark the cusp of proto-historic periods with emerging metallurgy.[11]Ancient Kingdoms and Dynasties

The region encompassing modern Nalgonda district in Telangana was integrated into the Satavahana Empire, which ruled the Deccan from approximately 230 BCE to 220 CE, originating from areas in present-day Telangana.[12] During this period, Nalgonda emerged as a significant center for Buddhism, with archaeological evidence indicating thriving monastic and trade activities under Satavahana patronage.[13] Succeeding the Satavahanas, the Ikshvaku dynasty controlled parts of the eastern Deccan, including sites in Nalgonda such as Nandikonda, from the 3rd to 4th centuries CE.[14] The Ikshvakus, known for their support of Mahayana Buddhism, constructed stupas, viharas, and pillared halls, as evidenced by excavations revealing brick structures and inscriptions linking the dynasty to the region's Buddhist heritage.[14] From around 380 CE to 611 CE, the Vishnukundina dynasty exerted influence over Nalgonda, with possible early capitals in the district and rulers including Indravarma (380–394 CE), Madhavavarman I (394–419 CE), and Govindavarman I (419–456 CE).[15] This Brahmanical dynasty promoted Shaivism and Jainism alongside residual Buddhist elements, as indicated by inscriptions and temple foundations in the area. The Badami Chalukyas extended their rule into Nalgonda by the 6th–8th centuries CE, leaving architectural legacies such as temples in Mudimanikyam village dated to the 8th–9th centuries via inscriptions, reflecting their Dravidian-style construction and administrative reach in the eastern Deccan.[16] These structures, including preserved shrines with unique label inscriptions, underscore Chalukya efforts to consolidate power post-Vishnukundina decline.[17]Medieval Rulers and Conflicts

During the 12th to early 14th centuries, the Kakatiya dynasty exerted significant control over the Nalgonda region, with the dynasty's foundational chief, Beta I, establishing an early kingdom in the Nalgonda district around the late 10th to early 11th century as a feudatory under the Western Chalukyas before asserting greater independence.[18] The Kakatiyas, ruling from 1158 to 1323 CE, promoted administrative stability and cultural patronage in the area, including through local feudatories like the Cheruku Chiefs, who governed as vassals from Cheraku in the Eruva region (present-day Nalgonda vicinity) between 1085 and 1323 CE, managing local defenses and revenues.[15][19] Kakatiya architectural influence is evident in sites like the Panagal temples, where inscriptions reference Prataparudra II (r. 1289–1323 CE), the last major ruler, who faced invasions leading to the dynasty's collapse in 1323 CE following Ulugh Khan's (Muhammad bin Tughluq) Delhi Sultanate campaigns that sacked Warangal and subdued regional strongholds including those near Nalgonda.[20] Following the Kakatiya decline, the Bahmani Sultanate conquered the Nalgonda area in the mid-14th century under Alauddin Bahman Shah (r. 1347–1358 CE), renaming the region from Neelagiri (an earlier Rajput designation) to Nallagonda, reflecting the "black hill" topography amid their expansion into the Deccan.[2] The Bahmanis consolidated rule through governors, but internal revolts emerged, such as in 1455 CE when Jalal Khan briefly declared independence as king at Nalgonda, only to be swiftly defeated and reintegrated into the sultanate under Ahmad Shah I (r. 1422–1436 CE).[21] This period saw fortified outposts like Panagal serve as strategic Bahmani holdings, though control fluctuated due to rivalries with emerging powers.[2] Persistent conflicts arose between the Bahmani Sultanate and the Vijayanagara Empire over Deccan border forts, including Nalgonda and Panagal, with Vijayanagara forces under Harihara II (r. 1377–1404 CE) occupying Panagal in 1398 CE for its tactical value in controlling trade routes and Krishna River access.[22] A notable clash, the Battle of Nalgonda-Pangal in 1419 CE, pitted Bahmani armies against Vijayanagara troops, resulting in temporary Bahmani reconquests but highlighting the ongoing tug-of-war that weakened both sides' grips on the region.[22] By the early 16th century, under Krishnadevaraya (r. 1509–1529 CE), Vijayanagara reasserted influence, capturing inland towns like Nalgonda from Bahmani successors amid their fragmentation into Deccan sultanates, though Bahmani forces had briefly reclaimed areas like Raichur Doab and adjacent territories around 1504 CE before reversals.[22] These Indo-Muslim-Hindu power struggles underscored Nalgonda's role as a contested frontier, with forts enduring sieges that shaped local allegiances and demographics through tribute systems and military garrisons.[22]Nizam's Rule and Telangana Rebellion

During the rule of the Seventh Nizam, Mir Osman Ali Khan (r. 1911–1948), Nalgonda district, as part of Hyderabad State's Telangana region, operated under a feudal agrarian system where approximately 40% of land was held by jagirdars—hereditary landlords granted estates by the Nizam—who wielded near-absolute authority over tenants.[23] These jagirdars imposed exorbitant rents often exceeding 50% of produce, enforced unpaid labor known as vetti, and maintained private militias to suppress dissent, leading to widespread peasant indebtedness and landlessness.[24] The Nizam's administration, characterized by autocratic centralization and resistance to modernization, exacerbated these conditions; despite nominal subsidiary alliances with the British until 1947, the state avoided reforms that might undermine feudal hierarchies, resulting in Telangana's per capita income lagging far behind British India.[25] Tensions escalated post-World War II amid the Nizam's bid for independent sovereign status or alignment with Pakistan, prompting the formation of the Razakar militia in 1938 under Bahadur Yar Jung, later led by Qasim Razvi after 1944, to enforce loyalty and combat pro-India sentiments.[24] In Nalgonda, Razakar raids targeted villages suspected of nationalist sympathies, including attacks on Hindu temples and forced conversions, while the Andhra Mahasabha—a cultural organization evolving into a political front—mobilized peasants against jagirdari oppression through village-level committees by the mid-1940s.[26] The Telangana Rebellion ignited on July 4, 1946, following the murder of peasant leader Kushtaswamy in Kadavendi village (Warangal district), but rapidly engulfed Nalgonda, where communist cadres of the Communist Party of India (CPI) assumed leadership, framing the uprising as class warfare against feudalism rather than solely anti-Nizam communalism.[24] By late 1946, rebels in Nalgonda liberated thousands of villages—estimates range from 3,000 to 5,000 across Telangana—establishing panch self-governing bodies that redistributed seized land, abolished forced labor, and organized guerrilla squads armed with farm tools and smuggled weapons.[27] Key actions included the November 1947 occupation of Aleru town under leaders like Asireddi Narasimhareddy, where flags were hoisted and administrative control asserted, alongside figures such as Ravi Narayana Reddy coordinating district-wide resistance.[28] The rebellion's intensity in Nalgonda stemmed from its dense rural population and historical grievances, with CPI estimates claiming over 4,000 villages under rebel control by 1947, though Nizam forces and Razakars retaliated with massacres, burning homes, and summary executions, contributing to thousands of deaths on both sides—official figures are contested, but peasant casualties likely exceeded 10,000.[26] Operation Polo, India's military intervention launched September 13, 1948, overwhelmed Razakar resistance within five days, leading to the Nizam's surrender on September 17 and Hyderabad's integration into the Indian Union; however, sporadic guerrilla fighting in Nalgonda persisted until the CPI's official withdrawal in October 1951, after which the Indian government implemented land reforms to address underlying feudal inequities.[25][24]Post-Independence Developments

Following Operation Polo on September 13-18, 1948, the princely state of Hyderabad, including Nalgonda district, was integrated into the Indian Union, ending Nizam rule.[29] The Telangana Rebellion, a communist-led peasant uprising that began in 1946 in districts like Nalgonda against feudal oppression, persisted briefly post-integration but was suppressed by 1951 through combined efforts of Indian forces and local authorities, leading to land reforms.[13] In 1956, under the States Reorganisation Act, the Telugu-speaking areas of Hyderabad State, including Nalgonda, merged with Andhra State to form Andhra Pradesh, with Nalgonda established as a district headquarters.[13] This administrative shift facilitated centralized planning for development, though regional disparities persisted.[3] A landmark project was the Nagarjuna Sagar Dam, constructed between 1955 and 1967 on the Krishna River in Nalgonda district, creating a reservoir with 11.472 billion cubic meters capacity for irrigation across 1.2 million hectares in Nalgonda and neighboring areas, alongside 816 MW hydropower generation.[30] The dam, the world's largest masonry structure at completion, boosted agricultural productivity in the region, shifting from rain-fed to irrigated farming, particularly paddy cultivation.[13] On June 2, 2014, Nalgonda became part of the newly formed state of Telangana following the Andhra Pradesh Reorganisation Act, enhancing focus on local infrastructure and industry, including cement factories and small-scale manufacturing that contributed to economic growth.[13] By 2019, district-level planning emphasized mandal decentralization for agriculture and rural development, though challenges like water management persisted.[3]Geography

Location and Physical Features

Nalgonda district occupies the central part of Telangana state in south-central India, with its administrative headquarters at Nalgonda city situated at approximately 17°03′N 79°16′E.[31] The district spans an area of 7,122 square kilometers, making it one of the larger districts in the state by land coverage.[1] It borders Suryapet district to the north, Yadadri Bhuvanagiri district to the northeast, Rangareddy district to the east, Nagarkurnool district to the south, and extends westward toward Andhra Pradesh regions.[32] The physical landscape of Nalgonda features undulating terrain typical of the Deccan Plateau, including residual hills, valleys, and plains that contribute to its drought-prone nature.[33] Elevations vary, with the district headquarters at an average of 420 meters above sea level and higher hill areas reaching up to 670 meters.[34] Predominant soils consist of red earth types such as loamy sands, sandy loams, and sandy clay loams, alongside patches of black cotton soil, which support dryland agriculture but require irrigation for optimal productivity.[35] Drainage in the district is primarily handled by the Krishna River and its tributaries, notably the Munneru River, which flow eastward and facilitate major irrigation infrastructure like the Nagarjuna Sagar Dam located within the district boundaries.[33] The granitic and gneissic rock formations underlying the area influence the hard terrain physiography, with rocky outcrops and limited alluvial deposits shaping agricultural and hydrological patterns.[36]Climate Patterns

Nalgonda district experiences a hot semi-arid climate marked by extreme summer heat, a monsoon-driven wet period, and mild winters, with annual temperatures averaging around 27°C. Maximum temperatures frequently surpass 40°C during the pre-monsoon summer months of March to May, peaking in May at approximately 41°C, while minimum temperatures dip to 19–21°C in January and December.[37][38] The district's diurnal temperature range is significant, often exceeding 10–15°C, contributing to arid conditions outside the rainy season. Precipitation is concentrated in the southwest monsoon from June to September, accounting for over 80% of the annual total of about 753 mm, with monthly averages ranging from 100–200 mm during peak months like July and August. Winter and summer months receive minimal rainfall, typically under 20 mm per month, leading to drought risks in non-monsoon periods. Inter-annual variability is high, with deviations from normal ranging from -43.7% to +22.2%, influenced by El Niño-Southern Oscillation patterns affecting regional monsoon strength.[39][40] Recent analyses indicate a warming trend in Nalgonda, with statistically significant increases in annual and seasonal maximum temperatures over the past decades, potentially exacerbating heat stress and water scarcity amid semi-arid baseline conditions. Relative humidity peaks at 70–80% during monsoon but drops to 30–40% in summer, while wind speeds average 5–10 km/h, occasionally gusting higher during thunderstorms.Rivers and Irrigation Systems

The Nalgonda district in Telangana is situated in the Krishna River basin, with the Krishna River forming a primary waterway that supports local agriculture and water resources. Major tributaries flowing through the district include the Musi River, which merges with the Krishna at Vadapally near Miryalaguda; the Dindi River; the Halia River; the Paleru River; the Aleru River; and the Peddavagu River. Additional streams such as Kangal and Chinnapalair also traverse the region, contributing to the district's hydrological network.[41][42][21] Irrigation infrastructure in Nalgonda heavily depends on multipurpose dams and canal systems drawing from these rivers, addressing the district's semi-arid conditions and variable rainfall. The Nagarjuna Sagar Dam, constructed on the Krishna River within the district, serves as the cornerstone project with a full reservoir level of 590 feet and storage capacity of 312.045 TMC, enabling irrigation across extensive ayacuts in Telangana, including stabilization of over 11 lakh acres via its right bank canal system.[43][30] This dam irrigates approximately 6.30 lakh acres in Telangana as part of its total 22 lakh acre command area shared with Andhra Pradesh.[44] Complementary projects include the Alimineti Madhava Reddy Project (Sriram Sagar Left Bank Canal extension) with an ayacut of 2,70,000 hectares; the Sri Ram Sagar Project Stage-II covering 2,07,064 hectares; and medium-scale initiatives like the Dindi Project, Utkur Marepalli Project, and Asifnagar Project, collectively stabilizing 23,338 hectares. Lift irrigation schemes, such as the R. Vidyasagar Rao Dindi Lift Irrigation Scheme and the Udaya Samudram Lift Irrigation Project commissioned in 2024, further augment water supply to upland and drought-prone mandals by pumping from reservoirs to canals, benefiting areas in Nalgonda and adjacent districts.[42][45]Environmental Issues

Fluorosis Epidemic

Nalgonda district in Telangana, India, experiences an endemic fluorosis epidemic primarily due to elevated fluoride concentrations in groundwater, which serves as the main drinking water source for rural populations reliant on borewells. Fluoride levels in the district's groundwater frequently exceed the World Health Organization's permissible limit of 1.5 mg/L, with concentrations reported up to 8.8 mg/L in some areas, driven by the region's granitic geology that releases fluoride through weathering and dissolution processes.[46][47] This chronic exposure, compounded by low calcium in local soils and water, exacerbates absorption and leads to widespread dental and skeletal fluorosis across villages.[48] Prevalence studies indicate severe impacts, with over 50% of residents in affected villages exhibiting both dental and skeletal manifestations, including mottled enamel, bone deformities, joint pain, and restricted mobility. In urban slums like Panagal in Nalgonda town, mean groundwater fluoride levels reach 4.01 mg/L, correlating with high rates of skeletal changes such as genu valgum and thoracic kyphosis among adults and children. Neurological symptoms, including headaches, lethargy, and memory impairment, have also been documented in fluorosis patients, with epidemiological surveys linking prolonged exposure to cognitive deficits in schoolchildren. About 95% of sampled groundwater sources in select villages surpass safe limits, affecting daily fluoride intake further amplified by dietary factors like tea consumption.[49][50][51][52] Mitigation efforts include the locally developed Nalgonda technique, involving alum-based precipitation for household defluoridation, though implementation has yielded mixed results due to inconsistent adoption and residual fluoride persistence. Government initiatives, such as fluoride monitoring by the Telangana administration and provision of surface water alternatives like Nagarjunsagar reservoir supplies (with 0.74 mg/L fluoride), aim to reduce reliance on contaminated borewells, which number over 5.5 lakh district-wide. Community-level programs have reported reductions in joint pain and urinary issues post-intervention, but challenges persist from extensive groundwater extraction and geological fluoride mobilization. Advanced methods like reverse osmosis and activated alumina adsorption show promise in lab settings but face scalability issues in rural contexts.[53][54][55][56]Industrial Pollution and Land Disputes

Nalgonda district hosts several cement manufacturing units, including Penna and Deccan Cements, which contribute to air pollution through emissions of particulate matter, respiratory organics, and inorganics. A 2017 study documented elevated respiratory health risks, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, among residents near these factories, attributing the issues to proximity to production sites.[57] Despite installations of air pollution control equipment like reverse air bag houses in all erstwhile Nalgonda cement units as of July 2025, local reports indicate persistent environmental and health concerns from dust and emissions affecting nearby agriculture and communities.[58] Chemical industries have exacerbated pollution, notably Deccan Chromates Limited in Damaracherla village, which ceased operations in 2012 after protests over worker health impacts including respiratory damage from hexavalent chromium exposure. The site left thousands of tonnes of untreated hazardous chromite waste, leaching carcinogenic substances into groundwater and surface water, contaminating farm produce, killing livestock, and causing vegetation die-off.[59] In 2017, villagers in Ammanabolu uncovered 13 tonnes of dumped pharmaceutical waste, prompting Telangana Pollution Control Board intervention, though enforcement gaps highlighted ongoing effluent disposal issues from regional pharma clusters.[60] Land disputes in Nalgonda often intersect with industrial expansion, as seen in opposition to proposed facilities on agricultural or contested lands. Activists and villagers in Wadapally resisted Krishna Godavari Power Utilities Limited's 2022 plan for a sodium dichromate-producing unit, citing unresolved legacy pollution from prior chromate operations that contaminated the Krishna River and caused nasal perforations and animal deaths since 2014; irregularities in environmental impact assessments, including omitted residue hazards, fueled claims of inadequate public consultation.[61] Similarly, Adani Group's Ambuja Cements expansion in the district faced stiff local resistance in January 2025 over land acquisition practices and fears of intensified air and water pollution in already burdened rural clusters.[62] These conflicts reflect broader tensions between industrial growth and land rights, with panchayat resolutions and deferred public hearings underscoring community demands for remediation before new projects.[59]Demographics

Population Statistics and Trends

As per the 2011 Census, Nalgonda district had a total population of 1,618,416, comprising 818,306 males and 800,110 females.[32][63] This yielded a sex ratio of 978 females per 1,000 males.[32] The district's population density stood at approximately 142 persons per square kilometer, reflecting its predominantly rural character over an area of about 11,408 square kilometers post-2016 administrative reorganization.[32] The population distribution showed 77.24% residing in rural areas and 22.76% in urban centers, underscoring limited urbanization compared to the state average.[32] Children under age 6 constituted about 11.25% of the total, indicating a relatively youthful demographic profile. Note that these figures account for boundary adjustments following Telangana's 2016 district reorganization, which apportioned 2011 Census data to the current Nalgonda district configuration, reducing its scope from the pre-bifurcation Andhra Pradesh era when the broader area reported over 3 million residents. Population growth decelerated notably in recent decades, with the decadal rate dropping to around 7.41% between 2001 and 2011 from 13.88% in the 1991–2001 period.[64][65] This slowdown aligns with broader trends in Telangana, driven by improved access to family planning, out-migration for employment to urban centers like Hyderabad, and agricultural constraints limiting local economic pull factors. Absent a post-2011 national census, official estimates remain unavailable, though provisional projections suggest modest annual growth of 0.5–1%, potentially reaching 1.8–1.9 million by 2025 based on state-level extrapolations.[66]Caste, Religion, and Linguistic Composition

According to the 2011 census, Hindus comprise 93.13% of the population in Nalgonda district, Muslims 5.41%, Christians 1.00%, Sikhs 0.03%, Buddhists 0.03%, and Jains 0.02%, with the remaining 0.38% following other religions or not stating one.[67]| Religion | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Hinduism | 93.13% |

| Islam | 5.41% |

| Christianity | 1.00% |

| Others | 0.46% |