Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nominalized adjective

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

A nominalized adjective is an adjective that has undergone nominalization, and is thus used as a noun. In the rich and the poor, the adjectives rich and poor function as nouns denoting people who are rich and poor respectively.

In English

[edit]The most common appearance of the nominalized adjective in English is when an adjective is used to indicate a collective group. This happens in the case where a phrase such as the poor people becomes the poor. The adjective poor is nominalized, and the noun people disappears. Other adjectives commonly used in this way include rich, wealthy, homeless, disabled, blind, deaf, etc., as well as certain demonyms such as English, Welsh, Irish, French, Dutch.

Another case is when an adjective is used to denote a single object with the property, as in "you take the long route, and I'll take the short". Here the short stands for "the short route". A much more common alternative in the modern language is the structure using the prop-word one: "the short one". However, the use of the adjective alone is fairly common in the case of superlatives such as biggest, ordinal numbers such as first, second, etc., and other related words such as next and last.

Many adjectives, though, have undergone conversion so that they can be used regularly as countable nouns; examples include Catholic, Protestant, red (with various meanings), green, etc.

Historical development

[edit]Nominal uses of adjectives have been found to have become less common as the language developed from Old English to Middle English and then Modern English. The following table shows the frequency of such uses in different stages of the language:[1]

| Period | Early OE (to 950) |

Late OE (950–1150) |

Early ME (1150–1350) |

Late ME (1350–1500) |

1500–1570 | 1570–1640 | 1640–1710 |

| Frequency of adjectives used as nouns (per 100,000 words) |

316.7 | 331.4 | 255.2 | 73.4 | 70.1 | 78.9 | 91.1 |

The decline in the use of adjectives as nouns may be attributed to the loss of adjectival inflection throughout Middle English. In line with the Minimalist Framework elaborated by Noam Chomsky,[2] it is suggested that inflected adjectives are more likely to be nominalized because they have overtly-marked φ-features (such as grammatical number and gender), which makes them suitable for use as the complement of a determiner.

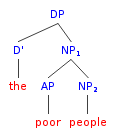

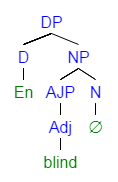

Determiners with unvalued φ-features must find a complement with a valued φ-feature to meet semantic comprehension.[1] In the diagrams below, the determiner is the, and its complement is either the noun phrase poor people or the nominalized adjective poor.

-

Tree diagram of determiner phrase with poor as an attributive adjective

-

Transformed determiner phrase with poor as nominalized adjective

The capacity of adjectives to be used as nouns is sometimes exploited in puns like The poor rich.

As the frequency of nominalized adjective use decreased, the frequency of structures using the prop-word one increased (phrases such as "the large" were replaced by those of the type "the large one"). In most other languages, there is no comparable prop-word, and nominalized adjectives, which in many cases retain inflectional endings, have remained more common.

In other languages

[edit]German

[edit]Adjectives in German change their form for various features, such as case and gender, and so agree with the noun that they modify. The adjective alt (old), for example, develops a separate lexical entry that carries the morphological and syntactic requirements of the head noun that has been removed:[3] the requirements are the inflectional endings of the language.

der

the.NOM.SG.MASC

Alt-e

old-NOM.SG.MASC

'the old man' (Sadock 1991)

den

the.ACC.SG.MASC

Alt-en

old-ACC.SG.MASC

'the old man' (Sadock 1991)

Here, der Alte is inflected for masculine gender, singular number and nominative case.[4] Den Alten is a similar inflection but in the accusative case. The nominalized adjective is derived from the adjective alt and surfaces as it does by taking the appropriate inflection.[3]

Swedish

[edit]Like in English, adjectival nouns are used as a plural definite ("the unemployed") and with nationality words ("the Swedish"). However, Swedish does not require "one or ones" with count nouns ("The old cat is slower than the new (one)"). The use of inflection, which incorporates the number and the gender of the noun, allows Swedish to avoid the need for a visible noun to describe a noun. That is also true in inflecting adjectival nouns.[5]

Standard use of an adjectival noun

[edit]

A noun phrase with both the noun and the adjective.[dubious – discuss]

A noun phrase with only the adjectival noun.[dubious – discuss]

Use of number and gender inflection

[edit]- ^ Swedish adjectives in definite form do not inflect for gender and number.

Ancient Greek

[edit]Ancient Greek uses nominalized adjectives without a "dummy" or generic noun like English "one(s)" or "thing(s)".[6] The adjective that modifies the noun carries information about gender, number and case and so can entirely replace the noun.

πολλαί

many.FEM.NOM.PL

"many women" (Balme & Lawall 2003) or "many things (of feminine gender)"

καλόν

beautiful.NEUT.NOM.SG

"a beautiful thing" or "a beautiful one"

τὸ

the.NEUT.NOM.SG

καλόν

beautiful.NEUT.NOM.SG

"the beautiful thing" or "the beautiful one"

Russian

[edit]In Russian, the conversion (or zero derivation) process of an adjective becoming a noun is the only type of conversion that is allowed. The process functions as a critical means of addition to the open class category of nouns.

Of all Slavic languages, Russian is the one that uses the attributive nouns the most. When the adjective is nominalized, the adjectival inflection alone expresses case, number and gender, and the noun is omitted.[7] For example, the Russian phrase «приёмная комната» (priyomnaya komnata, "receiving room") becomes «приёмная» (priyomnaya, "reception room"). The adjective "receiving" takes the nominal from "reception" and replaces the noun "room".

Many adjectival nouns in Russian serve to create nouns. Those common forms of nouns are known as "deleted nouns"; and there are three types:

The first type occurs in the specific context within a sentence or phrase and refers to the original noun that it describes. For example, in the sentence "Tall trees are older than short" the adjective "short" has become a noun and is assumed to mean "the short ones". Such a derivation is contextually sensitive to the lexical meaning of the phrase of which it is part.

The content-specific use of adjectival nouns also occurs in the second type in which nouns can be deleted, or assumed, in colloquial expressions. For example, in Russian, one might say «встречный» "oncoming" to refer to: 1) «встречный ветер» — headwind; 2) «встречный поезд» — train coming from the opposite direction; 3) «встречный план» — counter-plan; 4) «встречный иск» — counter-claim.

The third type is known as the "permanent" adjectival noun and has an adjective that stands alone as a noun. Such adjectives have become nouns over time, and most speakers are aware of their implicit adjectival meaning. For example, «прилагательное» (lit. "something, that apply something else") — the adjective.

Arabic

[edit]Nominalized adjectives occur frequently in both Classical Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic. An example would be الإسلامية al-ʾislāmiyyah "things (that are) Islamic", which is derived from the adjective إسلامي ʾislāmī "Islamic" in the inanimate plural inflection.

Another example would be الكبير al-kabīr "the big one" (said of a person or thing of masculine gender), from كبير kabīr "big" inflected in the masculine singular.

See also

[edit]- Collateral adjective

- Noun adjunct, a noun used as an adjective

- Adnoun, alternative term for nominalised adjective, alternative historical term for adjective

References

[edit]- ^ a b Yamamura, Shuto (2010). "The Development of Adjectives used as Nouns in the History of English". English Linguistics. 27 (2): 344–363. doi:10.9793/elsj.27.2_344.

- ^ Roger, Martin; Michael, David; Juan, Uriageraka (2000). "Minimalist Inquiries: The Framework," Step by Step: Essays on Minimalist Syntax in Honour of Howard Lasnik. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- ^ a b Sadock, Jerrold M. (1991). Autolexical syntax: A Theory of Parallel Grammatical Representations. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 41.

- ^ "Adjectival Nouns". Dartmouth.edu. Retrieved 2016-06-19.

- ^ a b c d e f Holmes, Philip; Hinchliffe, Ian (1994). Swedish: A compressive grammar (Second ed.). London and New York: Routledge. pp. 96–102.

- ^ Balme, Maurice; Lawall, Gilbert (2003). Athenaze (second ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 96.

- ^ Swan, Oscar (April 1980). "The Derivation of the Russian Adjectival Noun". Russian Linguistics. 4 (4): 397–404.