Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

North York

View on Wikipedia

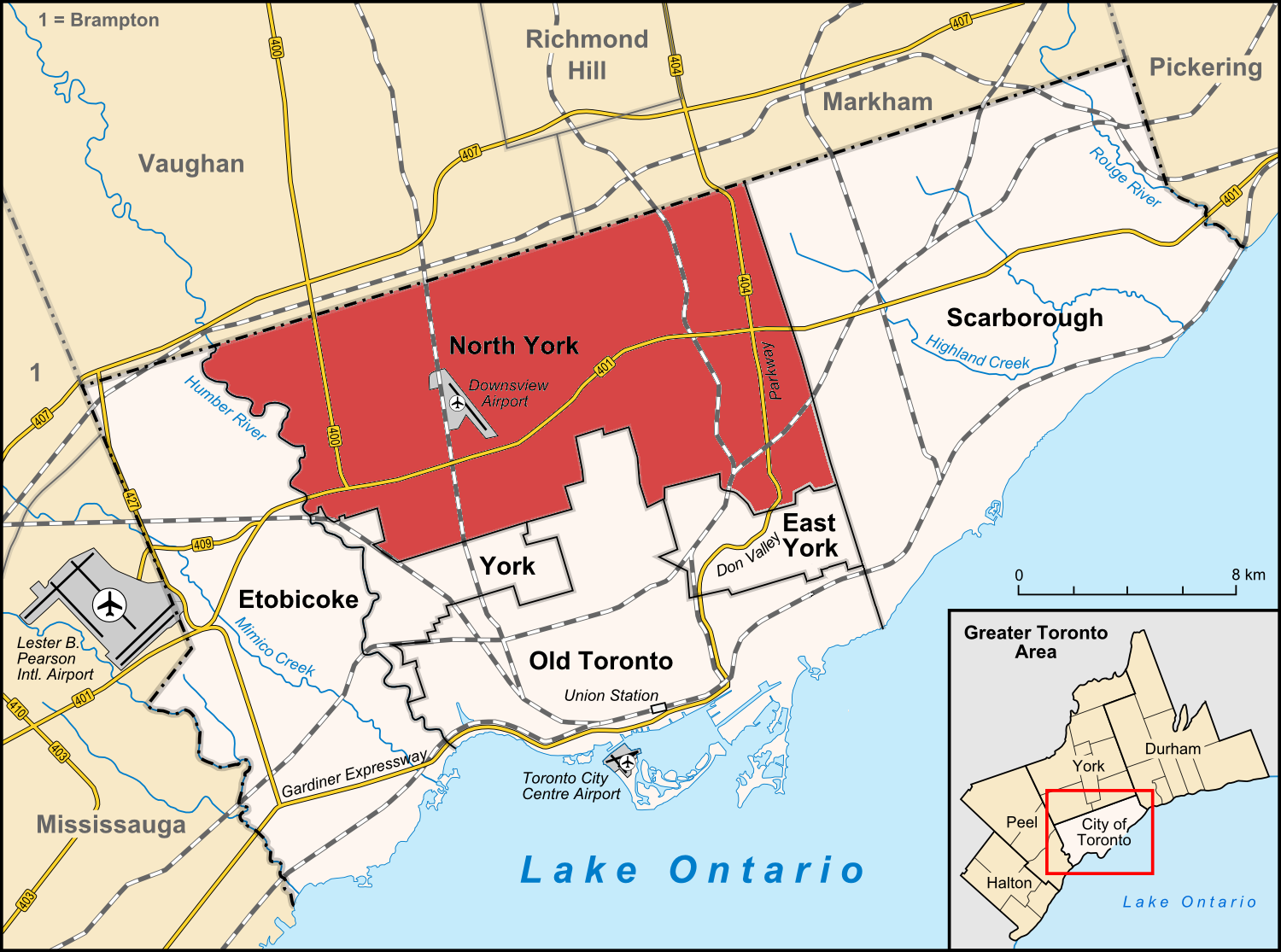

North York is a former township and city and is now one of the six administrative districts of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It is located in the northern area of Toronto, centred around Yonge Street, north of Ontario Highway 401. It is bounded by York Region to the north at Steeles Avenue, (where it borders Vaughan) on the west by the Humber River, on the east by Victoria Park Avenue. Its southern boundary is erratic and corresponds to the northern boundaries of the former municipalities of Toronto: York, Old Toronto and East York. As of the 2016 Census, the district has a population of 644,685.[2]

Key Information

North York was created as a township in 1922 out of the northern part of the former township of York, a municipality that was located along the western border of the-then City of Toronto. Following its inclusion in Metropolitan Toronto in 1953, it was one of the fastest-growing parts of Greater Toronto due to its proximity to Toronto. It was declared a borough in 1967, and later became a city in 1979, attracting high-density residences, rapid transit, and a number of corporate headquarters in North York City Centre, its planned central business district. In 1998, North York was dissolved as part of the amalgamation which created the new City of Toronto. It has since become a secondary economic hub of the city outside Downtown Toronto.

History

[edit]

The Township of North York was formed on June 13, 1922 out of the rural part of the Township of York. In the previous decade, the southern part of York, bordering the old City of Toronto had become increasingly urbanized while the northern portion remained rural farmland. The northern residents increasingly resented that they made up 20% of York's tax base while receiving few services and little representation in return, particularly after 1920 when their sole member on York's council, which was elected on an at-large basis, was defeated. Dairy farmer Robert Franklin Hicks organized with other farmers to petition the Ontario legislature to carve out what was then the portion of York Township north of Eglinton Avenue to create the separate township of North York.[3] With the support of the pro-farmer United Farmers of Ontario government, a plebiscite was organized and held and the 6,000 residents voted in favour of separating from York by margin of 393 votes.[4]

The township remained largely rural and agrarian until World War II. After the war, in the late 1940s and 1950s, a housing shortage led to the township becoming increasingly developed as a suburb of Toronto and a population boom. In 1953, the province federated 11 townships and villages with the Old City of Toronto, to become Metropolitan Toronto.

North York used to be known as a regional agricultural hub composed of scattered villages. The area boomed following World War II, and by the 1950s and 1960s, it resembled many other sprawling North American suburbs.

As North York became more populous, it became the Borough of North York in 1967, and then on February 14, 1979, the City of North York. To commemorate receiving its city charter on Valentine's Day, the city's corporate slogan was "The City with Heart".[5]

North York was amalgamated into Toronto on January 1, 1998. It now forms the largest part of the area served by the "North York Community Council", a committee of Toronto City Council.

Incidents

[edit]On August 10, 2008, a massive propane explosion occurred at the Sunrise Propane Industrial Gases propane facility just southwest of the Downsview Airport. This destroyed the depot and damaged several homes nearby. About 13,000 residents were evacuated for several days before being allowed back home. One employee at the company was killed in the blast and one firefighter died while attending to the scene of the accident.[6] A follow-up investigation to the incident made several recommendations concerning propane supply depots. It asked for a review of setback distances between depots and nearby residential areas but did not call for restrictions on where they can be located.[7][8][9][10][11]

Canada's deadliest pedestrian attack occurred in the North York City Centre district on April 23, 2018 when a van collided with numerous pedestrians killing 10 and injuring 16 others on Yonge Street between Finch and Sheppard Avenues.[12][13]

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for North York (1991−2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.5 (59.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

29.5 (85.1) |

34.0 (93.2) |

35.5 (95.9) |

36.0 (96.8) |

37.5 (99.5) |

34.5 (94.1) |

29.5 (85.1) |

23.0 (73.4) |

18.0 (64.4) |

37.5 (99.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −0.9 (30.4) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

5.1 (41.2) |

12.5 (54.5) |

19.8 (67.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.8 (80.2) |

22.9 (73.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

1.8 (35.2) |

13.6 (56.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.8 (23.4) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

0.4 (32.7) |

7.1 (44.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

4.2 (39.6) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −8.6 (16.5) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

1.7 (35.1) |

7.9 (46.2) |

13.3 (55.9) |

16.1 (61.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.8 (53.2) |

5.7 (42.3) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

4.1 (39.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26.0 (−14.8) |

−23.5 (−10.3) |

−25.5 (−13.9) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

3.0 (37.4) |

7.0 (44.6) |

5.5 (41.9) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−12.5 (9.5) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

−26.0 (−14.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 72.5 (2.85) |

53.3 (2.10) |

52.4 (2.06) |

74.1 (2.92) |

90.3 (3.56) |

85.5 (3.37) |

80.2 (3.16) |

74.0 (2.91) |

82.3 (3.24) |

66.7 (2.63) |

79.4 (3.13) |

61.3 (2.41) |

871.9 (34.33) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 37.2 (1.46) |

31.9 (1.26) |

29.2 (1.15) |

64.9 (2.56) |

90.3 (3.56) |

85.5 (3.37) |

80.2 (3.16) |

74.0 (2.91) |

82.3 (3.24) |

66.5 (2.62) |

69.6 (2.74) |

34.6 (1.36) |

746.2 (29.38) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 37.8 (14.9) |

21.1 (8.3) |

23.7 (9.3) |

5.5 (2.2) |

0.02 (0.01) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.1) |

10.5 (4.1) |

26.5 (10.4) |

125.2 (49.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 16.7 | 12.3 | 12.4 | 12.7 | 12.9 | 11.9 | 11.6 | 10.1 | 11.1 | 12.8 | 14.4 | 13.9 | 152.7 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 6.5 | 5.5 | 6.7 | 11.3 | 12.9 | 11.9 | 11.6 | 10.1 | 11.1 | 12.7 | 11.0 | 6.9 | 118.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 13.3 | 8.8 | 7.2 | 2.7 | 0.08 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.17 | 4.6 | 9.2 | 46.0 |

| Source 1: Meteostat[14] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Environment Canada (precipitation/rain/snow 1981–2010)[15] | |||||||||||||

Neighbourhoods

[edit]Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1931 | 13,210 | — |

| 1941 | 22,908 | +73.4% |

| 1951 | 85,897 | +275.0% |

| 1956 | 170,110 | +98.0% |

| 1961 | 269,959 | +58.7% |

| 1966 | 399,534 | +48.0% |

| 1971 | 504,150 | +26.2% |

| 1976 | 558,398 | +10.8% |

| 1981 | 559,521 | +0.2% |

| 1986 | 556,297 | −0.6% |

| 1991 | 562,564 | +1.1% |

| 1996 | 589,653 | +4.8% |

| 2001 | 608,288 | +3.2% |

| Source: Statistics Canada [16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23] | ||

| Ethnic groups in North York (2016) Source: 2016 Canadian Census[24] |

Population | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic origins | European | 349,150 | 40.6% |

| East Asian | 123,280 | 14.3% | |

| Southeast Asian | 85,115 | 9.9% | |

| Black | 84,415 | 9.8% | |

| South Asian | 75,995 | 8.8% | |

| Middle Eastern | 49,060 | 5.7% | |

| Latin American | 35,840 | 4.2% | |

| Aboriginal | 7,035 | 0.8% | |

| Other | 4,165 | 0.5% | |

| Total population | 869,401 | 100% | |

| Mother Tongue Languages | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| English | 280,320 | 43.9% |

| Mandarin | 40,125 | 6.3% |

| Persian | 30,465 | 4.8% |

| Tagalog (Pilipino, Filipino) | 28,810 | 4.5% |

| Cantonese | 27,665 | 4.3% |

| Russian | 20,320 | 3.2% |

| Korean | 19,265 | 3.0% |

| Spanish | 16,220 | 2.5% |

| Italian | 15,440 | 2.4% |

| Urdu | 10,325 | 1.6% |

| Others | 123,895 | 19.4% |

| Multiple Responses | 25,255 | 4.0% |

Economy

[edit]

The district's central business district is known as North York Centre, which was the location of the former city's government and major corporate headquarters. North York Centre continues to be one of Toronto's major corporate areas with many office buildings and businesses. The former city hall of North York, the North York Civic Centre, is located within North York City Centre.

Downsview Airport, near Sheppard and Allen Road, employs 1,800 workers.[26] Downsview Airport will be the location of the Centennial College Aerospace campus, a $60 million investment from the Government of Ontario and Government of Canada. Private partners include Bombardier, Honeywell, MDA Corporation, Pratt & Whitney Canada, Ryerson University, Sumitomo Precision Products Canada Aircraft, Inc. and UTC Aerospace Systems.[27]

Flemingdon Park, located near Eglinton and Don Mills, is an economic hub located near the busy Don Valley Parkway and busy Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) routes. McDonald's Canada and Celestica are located in this area, and Foresters Insurance has a major office tower and Bell Canada has a data centre. The Concorde Corporate Centre has 550,000 sq ft (51,000 m2) of leasable area and is 85% occupied with tenants such as Home Depot Canada, Sport Alliance of Ontario, Toronto-Dominion Bank, Esri Canada and Deloitte. Home Depot's Canadian head office is located in Flemingdon Park.[28]

North York houses two of Toronto's five major shopping malls: the Yorkdale Shopping Centre and Fairview Mall. Other neighbourhood malls locations include Centerpoint Mall, Bayview Village, Sheridan Mall, Yorkgate Mall, Shops at Don Mills, Steeles West Market Mall, Jane Finch Mall and Sheppard Centre.

Health care is another major industry in North York, with the district housing several major hospitals, including the North York General Hospital, Humber River Hospital and the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Education

[edit]

Prior to 1998, the North York Board of Education and Conseil des écoles françaises de la communauté urbaine de Toronto operated English and French public secular schools in North York, while the Metropolitan Separate School Board operated English and French public separate schools for North York pupils. Today, four public school boards operate primary and secondary institutions in the former city:

- Conseil scolaire catholique MonAvenir (CSCM)

- Conseil scolaire Viamonde (CSV)

- Toronto Catholic District School Board (TCDSB)

- Toronto District School Board (TDSB)

CSV and TDSB operate as secular public school boards, the former operating French first language institution, whereas the latter operated English first language institutions. The other two school boards, CSCM and TCDSB, operate as public separate school boards, the former operating French first language separate schools, the latter operating English first language separate schools. All four public school boards are headquartered within North York.

In addition to primary and secondary schools, several post-secondary institutions were established in North York. York University is a university that was established in 1959. The university operates two campuses in North York, the Keele campus located in the north, and Glendon College, a bilingual campus operated by the university. There are also two colleges that operate campuses in North York. Seneca College was established in North York in 1967, and presently operates several campuses throughout North York, and Greater Toronto. One of Centennial College's campuses are also located in North York, known as the Downsview Park Aerospace Campus.

Governance

[edit]North York is a district of the City of Toronto, and is represented by councillors elected to the Toronto City Council, members elected to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, as well as members elected to the Parliament of Canada. North York Civic Centre is presently used by North York's community council and other city departments servicing North York.

Prior to North York's amalgamation with Toronto in 1998, North York operated as a lower-tier municipality within the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto. The municipality operated its own municipal council, the North York City Council, and met at the North York Civic Centre prior to the municipality's dissolution. The following is a list of reeves (1922–1966) and mayors (1967–1997) of North York.

Reeves and mayors

[edit]Township of North York

- 1922–1929 Robert Franklin Hicks – born in 1866, Hicks was a dairy farmer who organized with other farmers to petition the Ontario legislature to carve out what was then the portion of York Township north of Eglinton Avenue to create the separate township of North York.[3] During his period as the first reeve, the North York Hydro Commission, a public health board, and a water supply system were created and improvements were made to Yonge Street and other local roads. Hicks died in 1942.[29]

- 1929–1930 James Muirhead – farmer in Leslie and Lawrence Ave area. Born in 1859 and lived on the same farm all of his life up to 1929 except for four years. Was chairman of the committee responsible for breaking North York away from York Township and a founding members of the township council.[30][31]

- 1931–1933 George B. Elliott – also served as warden of York county in 1933. As reeve, faced demands for improved unemployment relief as the Depression worsened.[32] Appointed inspector of hospital accounts for indigent patients in York county in 1934. Announced he would run for the federal Conservatives in a York North in 1934 but withdrew his name from consideration.[33]

- 1934–1940 Robert Earl Bales – great-grandson of area pioneer John Bales, Earl Bales was North York's youngest reeve at 37. Earl Bales Park, which is on his family's former farmland, is named after him.[34] Like many municipalities, North York was bankrupted by the cost of paying unemployment relied during the Great Depression. Under Bales' leadership, North York was one of the few bankrupted municipalities to be able to pay off its debt. Unlike many other Ontario municipalities, North York never seized any homes or farms for non-payment of taxes.[35] Bales later sat on the North York planning board from 1947 until 1968.[36]

- 1941–1949 George Herbert Mitchell also served in the Ontario legislature as CCF MPP for York North from 1943 to 1945, while serving as reeve.[37] As reeve, kept track of expectant mothers come snowfall to ensure that the township's two snowplows kept open the sideroads around their homes. Mitchell was the last reeve to be elected by a predominantly rural electorate.[38]

- 1950–1952 Nelson A. Boylen – reporter for The Evening Telegram (1912–1918) then in the dairy industry for 50 years. Served as a school trustee and then deputy reeve. Opposed the amalgamation of North York into Metropolitan Toronto, arguing that water shortages could be solved by creating a provincial water authority instead. Denied charges that North York was broke. Defeated in 1952 but later served as a councillor. Appointed to the Metro Toronto & Region Conservation Authority in the 1960s.[39]

- 1953–1956 Frederick Joseph McMahon – supported the creation of Metropolitan Toronto. Ran as the Ontario Liberal Party candidate in York Centre in the 1955 provincial election, but was unsuccessful. A lawyer by profession, he was best known for defending bank robber Edwin Alonzo Boyd and his brother. McMahon later served as a provincial court judge.[40][41][42]

- 1957–1958 Vernon M. Singer – went on to serve as MPP from 1959 to 1977

- 1959–1964 Norman C. Goodhead – as reeve, opposed illegal basement apartments and led a campaign to evict tenants. Stood for position of Metro Toronto Chairman in 1962 but lost to William Allen by four votes. Ran again for Metro Chairman in 1969, when no longer mayor, but lost to Scarborough mayor Albert Campbell.[43][44]

- 1965–1966 James Ditson Service – defeated incumbent reeve Goodhead by running against Goodhead's support for amalgamating North York and the rest of Metro Toronto into a unitary city and alleging Goodhead was in a conflict of interest by owning a garbage disposal company that did business with the borough. Service campaigned on building the North York Civic Centre on Yonge Street and developing the area as a downtown with high-density office buildings. He also advocated building a 62,000 domed stadium on surplus land transferred from Downsview Airport. In private business, he co-founded CHIN Radio/TV International with Johnny Lombardi, also founding CHIN (AM) radio but later fell out with him. After he was mayor, Service became a property developer.[45][46][47]

Borough of North York

- 1967–1969 James Ditson Service

- 1970–1972 Basil H. Hall – supported the construction and extension of the Spadina Expressway and continued to do so after the provincial government cancelled the project. After he was mayor, he served on the board of the provincially owned Urban Transportation Development Corporation.[48]

- 1973–1978 Mel Lastman

City of North York

- 1979–1997 Mel Lastman – served as first mayor of the amalgamated city of Toronto from 1998 to 2003.

Board of Control

[edit]

North York had a Board of Control from 1964 until it was abolished with the 1988 election and replaced by directly elected Metro Councillors. The Board of Control consisted of four Controllers elected at large and the mayor and served as the executive committee of North York Council. Controllers concurrently sat on Metropolitan Toronto Council

Names in italics indicate Controllers that were or became Mayor of North York in other years.

X = elected as Controller

A = appointed Controller to fill a vacancy

M = sitting as Reeve or Mayor

| Controller | 1964 | 1966 | 1969 | 1972 | 1974 | 1976 | 1978 | 1980 | 1982 | 1985 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| James Ditson Service | M | M | ||||||||

| G. Gordon Hurlburt | X | X | ||||||||

| Irving Paisley | X | X | X | |||||||

| Frank Watson | X | X | ||||||||

| Basil H. Hall | X | X | M | |||||||

| Paul Hunt | X | X | ||||||||

| Mel Lastman | X | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | ||

| John Booth[A] | X | |||||||||

| Paul Godfrey[A] | A | X | ||||||||

| John Williams | X | |||||||||

| Alex McGivern | X | X | ||||||||

| Barbara Greene | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| William Sutherland[A] | A | X | X | X | ||||||

| Joseph Markin | X | |||||||||

| Esther Shiner[B] | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Ron Summers | X | |||||||||

| Robert Yuill | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Norm Gardner | X | X | ||||||||

| Howard Moscoe | X | |||||||||

| Mario Gentile | A |

^A Booth died in 1970 and was replaced by Paul Godfrey who served out the balance of his term.[49] Godfrey was reelected in 1972, but resigned when he was elected Metro Chairman in 1973 following the death of Metro Chairman Albert Campbell. North York Council elected Alderman William Sutherland to replace Godfrey on the Board of Control on July 23, 1973.[50]

^B Shiner died on 19 December 1987. Councillor Mario Gentile was appointed to the Board of Control in February 1988 to fill Shiner's seat.[51]

Media

[edit]- North York Mirror: A weekly community newspaper (thrice and then twice weekly in earlier times) covering North York. Part of Torstar's Metroland chain of community newspapers. The newspaper was launched in 1957 and ceased publication in 2023 when it was folded into the toronto.com website along with other Toronto-based Metroland titles.[52]

- Salam Toronto: Bilingual Persian-English weekly paper for the Iranian community of North York.

Recreation

[edit]Museums

[edit]

North York is home to several museums including the (now closed) Canadian Air and Space Museum (formerly the Toronto Aerospace Museum) in Downsview Park. The closed museum was relocated to Edenvale, Ontario in 2019 (northwest of Barrie) and opened and renamed as the "Canadian Air and Space Conservancy".[53] North York is also home to a number of interactive museums, including Black Creek Pioneer Village, an authentic nineteenth-century village and a living museum, the Ontario Science Centre was an interactive science museum which was permanently closed in June, 2024, and the Aga Khan Museum, which includes a collection of Islamic art from the Middle-East and Northern Africa.

Sports

[edit]

An aircraft manufacturing facility and a former military base are located in the Downsview neighbourhood. With the end of the Cold War, much of the land was transformed into a large park now called Downsview Park. Located within the park is the Downsview Park Sports Centre, a 45,000 m2 (484,000 sq ft) multi-purpose facility built by Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment (MLSE), owners of Toronto FC, of Major League Soccer. MLSE invested $26 million to build the Kia Training Ground, the state-of-the-art practice facility for Toronto FC. Volleyball Canada made Downsview Park its headquarters and training facility.

There are a multitude of sports clubs based in North York including the North York Storm, a girls' hockey league, Gwendolen Tennis Club, and the North York Aquatic Club, which was founded in 1958 as the North York Lions Swim Club.[54] The Granite Club, located at Bayview and Lawrence, is an invitation-only athletic club. In 2012, the club made a major expansion in North York for their members.

The Oakdale Golf & Country Club is a private, parkland-style golf and tennis club located in North York. It hosted the 2023 Canadian Open, and will host the tournament again in 2026.[55][56]

The North York Ski Centre at Earl Bales Park is one of the only urban ski centres of its kind in Canada. After several incidents involving failures of the club's two-person chairlift incited talks of closing the ski centre, the city revitalized the facilities with a new four-person chairlift. Sports clubs based in North York include:

- York United FC – member of Canadian Premier League[57]

- Toronto FC II – member of USL League One[58]

- North York Astros[59] – member of Canadian Soccer League

- North York Rockets – (defunct) Canadian Soccer League (1987–1992)

- North York Rangers – member of the Central Division of the

Ontario Junior Hockey League

Transportation

[edit]Several major controlled-access highways pass through North York, including Highway 400, Highway 401, Highway 404, Allen Road, and the Don Valley Parkway. The former three controlled access highways are operated by the province as 400-series highways, whereas the latter two roadways are managed by the City of Toronto. The section of Highway 401 which traverses North York is the busiest section of freeway in North America, exceeding 400,000 vehicles per day,[60][61] and one of the widest.[62][63]

Public transportation in North York is primarily provided by the Toronto Transit Commission's (TTC) bus or subway system. Two lines of the Toronto subway have stations in North York, the Line 1 Yonge–University, and Line 4 Sheppard. Finch station, the terminus of the Yonge Street branch of the Yonge–University line, is the busiest TTC bus station and the sixth-busiest subway station, serving around 97,460 people per day.[citation needed] The Line 4 Sheppard subway which runs from its intersection with the Yonge-University line at Sheppard Avenue easterly to Fairview Mall at Don Mills Road, is entirely in North York, averaging around 55,000 riders per day. [citation needed] Line 5 Eglinton is a light rail line that is under construction and will traverse through the southeast portion of North York. Line 6 Finch West is another line under construction and will traverse through the northwestern portion of North York. The Ontario Line is expected to have two stops in North York, Science Centre and Flemingdon Park. The intersection of York Mills and Yonge, located next to York Mills station is home to an office and a TTC commuter parking lot, which was sold for $25 million. A $300-million project is expected to create about 300 jobs and bring a new hotel, perhaps a four star Marriott, to the intersection.[64]

In addition to the TTC, other public transit services that may be accessed from North York include GO Transit, and York Region Transit. GO Transit provides access to commuter rail and bus services to communities throughout Greater Toronto. Both services may be accessed at GO or TTC stations located in North York.

Notable people

[edit]- Michael Adamthwaite (born 1981), voice actor

- Liane Balaban (born 1980), actress

- Andy Borodow (born 1969), Olympic wrestler

- John Bregar, actor

- Chris Campoli, professional ice hockey player

- Candi & The Backbeat, pop band

- Kurtis Conner (born 1994), stand-up comedian and YouTuber

- Tie Domi, former professional ice hockey player

- Louis Ferreira, actor

- Yani Gellman (born 1985), film and television actor

- Paul Godfrey, former president of the Toronto Blue Jays and former chairman of Metropolitan Toronto

- James Hinchcliffe, professional auto racing driver, born here

- Adrianne Ho, model, designer, and director

- Michael Kerzner, Solicitor General of Ontario

- Mel Lastman, long-time Mayor of North York, and the first Mayor of the amalgamated city of Toronto

- Nicholas Latifi, professional auto racing driver, grew up in North York

- Geddy Lee, rock musician

- Matt Moulson, professional ice hockey player

- George Nagy (born 1957), Olympic swimmer in the butterfly

- Peter Polansky (born 1988), tennis player

- Rambha, Indian actress, settled here

- Gary Roberts, former professional ice hockey player

- Ya'ara Saks, Canadian Minister of Mental Health and Addictions and Associate Minister of Health

- Sam Schachter (born 1990), Olympic beach volleyball player

- Barry Sherman, pharmaceutical company executive and founder of Apotex.

- Olivia Smith, soccer player for the Canada national team

- Snow, reggae musician

- Andy Yerzy (born 1998), baseball catcher and first baseman in the Milwaukee Brewers organization

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "North York". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada.

- ^ "North York – City of Toronto Community Council Area Profiles" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Scott (November 11, 2013). Willowdale: Yesterday's Farms, Today's Legacy. Dundurn. ISBN 978-1-4597-1751-0. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- ^ "Opinion | Overtaxed and underserviced, North York broke away from Toronto in 1922". July 13, 2018. Archived from the original on August 4, 2021. Retrieved August 4, 2021.

- ^ "Progress, Economy & Heart – North York Grows Up". City of Toronto. Archived from the original on November 28, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ Thousands returning home after massive T.O. fire. Archived August 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine CTV News. August 10, 2008.

- ^ Boost 'hazard distance' at propane depots: report. Archived March 7, 2023, at the Wayback Machine CTV News. November 7, 2008.

- ^ "Residents 'Very Lucky' After Massive Explosion At Propane Facility Sparks Huge Evacuation". CityNews. August 10, 2008. Archived from the original on August 13, 2008.

- ^ "Thousands returning home after massive T.O. fire". CTV. Archived from the original on August 19, 2008.

- ^ "Residents return after blast". Toronto Star. August 11, 2008. Archived from the original on December 26, 2013.

- ^ "401 reopens – finally". Toronto Star. August 10, 2008. Archived from the original on August 11, 2008.

- ^ Austen, Ian; Stack, Liam (April 23, 2018). "Toronto Van Plows Along Sidewalk, Killing 10 in 'Pure Carnage'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ "All 10 of those killed in Toronto van attack identified". CBC. Archived from the original on May 3, 2018. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

- ^ "North York, Ontario Climate Normals 1991–2020". Meteostat. Retrieved August 12, 2025.

- ^ "Toronto North York". Canadian Climate Normals 1981–2010. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ "Table 12: Population of Canada by provinces, counties or census divisions and subdivisions, 1871-1931". Census of Canada, 1931. Ottawa: Government of Canada. 1932.

- ^ "Table 2: Population of Census Subdivisions, 1921–1971". 1971 Census of Canada. Vol. I: Population, Census Subdivisions (Historical). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1973.

- ^ "Table 3: Population for census divisions and subdivisions, 1971 and 1976". 1976 Census of Canada. Census Divisions and Subdivisions, Ontario. Vol. I: Population, Geographic Distributions. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1977.

- ^ "Table 4: Population and Total Occupied Dwellings, for Census Divisions and Subdivisions, 1976 and 1981". 1981 Census of Canada. Vol. II: Provincial series, Population, Geographic distributions (Ontario). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1982. ISBN 0-660-51092-8.

- ^ "Table 2: Census Divisions and Subdivisions – Population and Occupied Private Dwellings, 1981 and 1986". Census Canada 1986. Vol. Population and Dwelling Counts – Provinces and Territories (Ontario). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1987. ISBN 0-660-53460-6.

- ^ "Table 2: Population and Dwelling Counts, for Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions, 1986 and 1991 – 100% Data". 91 Census. Vol. Population and Dwelling Counts – Census Divisions and Census Subdivisions. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1992. ISBN 0-660-57115-3.

- ^ "Table 10: Population and Dwelling Counts, for Census Divisions, Census Subdivisions (Municipalities) and Designated Places, 1991 and 1996 Censuses – 100% Data". 96 Census. Vol. A National Overview – Population and Dwelling Counts. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. 1997. ISBN 0-660-59283-5.

- ^ "2001 Community Profiles: North York, Ontario (City / Dissolved)". Statistics Canada. Retrieved September 13, 2025.

- ^ "Census Profile, 2016 Census York Centre [Federal electoral district], Ontario and Ontario [Province]". Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2019.,

"Census Profile, 2016 Census Don Valley West [Federal electoral district], Ontario and Ontario [Province]". Archived from the original on April 29, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2019.,

"Census Profile, 2016 Census Don Valley East [Federal electoral district], Ontario and Ontario [Province]". Archived from the original on March 26, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2019.,

"Census Profile, 2016 Census Willowdale [Federal electoral district], Ontario and Ontario [Province]". February 8, 2017. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2019.,

"Census Profile, 2016 Census Eglinton–Lawrence [Federal electoral district], Ontario and Ontario [Province]". February 8, 2017. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2019.,

"Census Profile, 2016 Census Humber River–Black Creek [Federal electoral district], Ontario and Ontario [Province]". Archived from the original on April 29, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2019.,

"Census Profile, 2016 Census York South–Weston [Federal electoral district], Ontario and Ontario [Province]". Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2019.,

"Census Profile, 2016 Census Don Valley North [Federal electoral district], Ontario and Ontario [Province]". Archived from the original on April 29, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2019. - ^ "North York – City of Toronto Community Council Area Profiles (2016 Census)" (PDF). The City Planning Division of City of toronto. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved October 10, 2022.

- ^ Queen, Lisa (April 18, 2012). "Aerospace campus for Downsview Park?". Inside Toronto. Metroland Media. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 5, 2015.

- ^ Arnaud-Gaudet, Nicolas. "Centennial College To Build Aerospace Campus at Downsview Park". Urban Toronto. Archived from the original on March 31, 2015. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ "Concorde Corporate Centre". Artis REIT. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "Children get history lesson as park plaque unveiled". North York Mirror. December 9, 2010. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ "Model T powered North York revolt" by Harold Hilliard, Toronto Star, 16 July 1985, p. 18.

- ^ "Quintette of solid men in council of North York", Toronto Daily Star, 23 January 1928, p. 20.

- ^ "Industrial Feudalism Seen As Great Peril", Toronto Daily Star, 7 November 1933, p. 20.

- ^ Earl Rowe Is Prospective Leader of Conservatives, Toronto Daily Star, 30 July 1934, p. 14

- ^ "Plaque celebrates history of John Bales House". April 8, 2015. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ "The dirty thirties: $6.33 a week to feed 4" by Harold Hilliard, Toronto Star, 15 March 1988, p. N12.

- ^ Names that grace parks, Toronto Star, 5 September 2000, p. B3.

- ^ "York North Is Riding of Political Changes", Globe and Mail, 2 June 1948, p. 4.

- ^ "Post-war rush ended rural air of North York", Toronto Star, 23 April 1985, p. M16

- ^ "Former reecr in North York fought merger", Globe and Mail, 30 April 1973, p. 2.

- ^ "McMahon, Frederick Joseph", Toronto Star (1971–2009); Toronto, Ontario [Toronto, Ontario] 07 Mar 1988: C10., "McMahon defeats Boylen in N. York", Toronto Daily Star (1900–1971); Toronto, Ontario [Toronto, Ontario]02 Dec 1952: 22., "York Centre: Reeve and Deputy Vie for Seat in New Riding", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]02 June 1955: 4, "3 Big Issues in North York Election, The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont] 02 Dec 1950: 4., "Lawyer Provides Upset: 3-Time North York Reeve Beaten", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]02 Dec 1952: C5., "Mayors, Reeves Happy, Yet Fearful Suburbs May Be Rubber Stamps", by Alden Baker, The Globe and Mail, 22 Jan 1953: 9, "North York Nearly Bankrupt, Metro Saved It, Reeve Says", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]18 Jan 1955: 4, "Acclaim McMahon In North York; Race for Council", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]24 Nov 1953: 5., "Fred McMahon Is Re-elected N. York Reeve", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]06 Dec 1955: 13, "Vote 3-to-2 to Appeal Ruling on Fluoridation", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]28 Mar 1956: 5., Canadian Press (1955-06-10)., "Reeve Retires After 4 Years In North York", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]14 Sep 1956: 5., "Ratepayers Ask Probe On Land Deal Charge", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]17 June 1960: 9, "North York Officials Confer on Land Sale", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]18 June 1960: 4

- ^ Vallee, Brian (December 14, 2011). Edwin Alonzo Boyd: The Story of the Notorious Boyd Gang. Doubleday Canada. ISBN 978-0-385-67439-3. Archived from the original on May 13, 2023. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ^ "3 made provincial judges to ease Metro workload", Toronto Daily Star (1900–1971); Toronto, Ontario [Toronto, Ontario]20 Sep 1969: A2., "Just rewards:: Metro councillors go on to bigger and better things", by Alden Baker, The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]19 July 1976: 5.

- ^ "Norman Goodhead, 92: Former North York reeve". Toronto Star. October 5, 2009. Archived from the original on October 26, 2023. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ^ "Former reeve Norman Goodhead dies". Toronto.com. October 6, 2009. Archived from the original on October 26, 2023. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ^ "Candidates for Mayor", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]02 Dec 1966: 12., "James Ditson Service 1926–2014", Toronto Star (2010– Recent); Toronto, Canada [Toronto, Canada]06 Aug 2014: GT7., "Service still wants sportsdome: A family decision", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont] 22 Oct 1969: 5, "Lombardi buys out Service", Staff. The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]18 June 1970: 10., "Mayors ain't what they used to be": [1 Edition] Toronto Star; Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]26 Jan 1999: 1. "MUNICIPAL AFFAIRS: James Service: a mandate for change in North York", Godfrey, Scott. The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont] 23 Jan 1965: 9.

- ^ "Resources on Former Municipalities". City of Toronto. September 18, 2017. Archived from the original on June 21, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ^ "They'd pave paradise", The Globe and Mail; Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont] 12 Dec 1981: F.3. , "High-density project for Yonge-Sheppard gets OMB approval", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]23 Jan 1971: 5.,"Service cleans out the office of mayor", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]25 Dec 1969: 8, "Service's North York tower approved", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]05 Feb 1977: 5, "FROM THE ARCHIVES", The Globe and Mail; Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]25 June 1994: A.2., "Where are they now? BUZZIE BAVASI Baseball" Patton, Paul. The Globe and Mail; Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]20 Feb 1988: C.7., "North York names 17 io work toward dome, major-league teams", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]01 Apr 1970: 31, "In 1540 Slot: Lombardi Approved In Radio Proposal", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]25 June 1965: 15. "Lombardi keeps CHIN frequency", The Globe and Mail (1936–2016); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]07 Nov 1970: 29

- ^ "Former mayor promoter of downtown North York". Globe and Mail. April 28, 1990., "Obituary: North York ex-mayor Basil Hall". Toronto Star. April 27, 1990., "Candidates for Controller". Globe and Mail. December 2, 1966.,"Hall has back-scratching society, Liberals say: Only one question in North York mayoral race: how can Barbaro win?". Globe and Mail. November 25, 1969., "Hall sees victory as party repudiation". Globe and Mail. December 2, 1969., "Mayor suggests Spadina extension to Gardiner: Hall, an expressway booster, inaugurated in North York". Globe and Mail. January 6, 1970.,"'Not pussy-footing,' North York decides". Globe and Mail. September 12, 1972.

- ^ "Godfrey captures vacant seat on North York Board of Control", The Globe and Mail (1936–Current); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]26 Sep 1970

- ^ "North York vacancy filled by Sutherland" The Globe and Mail (1936–Current); Toronto, Ont. [Toronto, Ont]24 July 1973: 5

- ^ "North York seeks councillor to fill seat that Gentile vacated", Toronto Star, 2 February 1988

- ^ Adler, Mike (December 14, 2023). "Looking for past print issues of your local Metroland Toronto community newspaper? Here's where to look". toronto.com. Archived from the original on January 2, 2024. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ "Canada Aviation and Space Museum". Government of Canada. September 27, 2017. Archived from the original on October 22, 2021. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- ^ 2010-2011 NYAC Handbook Archived March 7, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, p 4.

- ^ "Oakdale Golf & Country Club to host 2023 & 2026 RBC Canadian Open". Golf Canada. May 19, 2021. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ "Canadian Open to be held at Toronto's Oakdale Golf and Country Club in 2023, 2026". CBC Sports. May 19, 2021. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ^ "York9 FC – Our Stadium". Archived from the original on February 15, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ "USL League One – Toronto FC II Schedule". Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- ^ North York Astros Archived November 24, 2002, at the Wayback Machine Men's professional soccer playing in the Canadian Soccer League. Esther Shiner Stadium.

- ^ Allen, Paddy (July 11, 2011). "Carmageddon: the world's busiest roads". The Guardian. Guardian News & Media Ltd. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- ^ Maier, Hanna (October 9, 2007). "Chapter 2". Long-Life Concrete Pavements in Europe and Canada (Report). Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

The key high-volume highways in Ontario are the 400-series highways in the southern part of the province. The most important of these is the 401, the busiest highway in North America, with average annual daily traffic (AADT) of more than 425,000 vehicles in 2004 and daily traffic sometimes exceeding 500,000 vehicles.

- ^ Canadian NewsWire (August 6, 2002). Ontario government investing $401 million to upgrade Highway 401 (Report). Ministry of Transportation of Ontario.

Highway 401 is one of the busiest highways in the world and represents a vital link in Ontario's transportation infrastructure, carrying more than 400,000 vehicles per day through Toronto.

- ^ Thün, Geoffrey; Velikov, Kathy. "The Post-Carbon Highway". Alphabet City. Archived from the original on July 5, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

It is North America's busiest highway, and one of the busiest in the world. The section of Highway 401 that cuts across the northern part of Toronto has been expanded to eighteen lanes, and typically carries 420,000 vehicles a day, rising to 500,000 at peak times, as compared to 380,000 on the I-405 in Los Angeles or 350,000 on the I-75 in Atlanta (Gray).

- ^ Pigg, Susan (January 14, 2015). "York Mills TTC parking lot slated for hotel, office complex". Toronto Star. Torstar. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved April 10, 2015.

External links

[edit] Media related to North York at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to North York at Wikimedia Commons- City of Toronto: North York Community Council

North York

View on GrokipediaNorth York was a municipality in Ontario, Canada, incorporated as a city in 1979 and dissolved on January 1, 1998, through provincial legislation that amalgamated it with Toronto, Etobicoke, Scarborough, York, East York, and Metro Toronto to form a unified "megacity."[1][2] Originally established as the Township of North York on June 13, 1922, from largely agrarian lands severed from York Township to the south, it evolved into a borough in 1967 amid accelerating suburban expansion.[3][4] Post-1950s population growth transformed North York from rural farmland into a hub of residential high-rises, commercial strips along Yonge Street, and early industrial complexes, with developers constructing housing, shopping centres, parks, and cultural facilities to accommodate surging demand.[5][6] Under Mayor Mel Lastman, who served from 1973 to 1997, the city prioritized fiscal restraint with consistently low property taxes, oversaw $4 billion in redevelopment along its main Yonge Street corridor, and cultivated a distinct civic identity as "The City with Heart."[7][1][8] The 1998 amalgamation, driven by the Ontario Progressive Conservative government's aim to streamline services and achieve economies of scale, faced strong local opposition from North York's council and residents, who valued its autonomous governance and efficiency; subsequent analyses have questioned whether promised cost savings materialized amid rising administrative complexities.[9][10][11]

History

Early Settlement and Township Formation

The lands encompassing present-day North York were originally inhabited by the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, who surrendered approximately 250,808 acres to the British Crown via the Toronto Purchase on September 23, 1787, in exchange for goods including gun flints and rum, though the agreement's boundaries remained disputed until a settlement in 2010.[12] Following the creation of Upper Canada in 1791, which included York County, European settlement in the region began in earnest after the opening of Yonge Street in 1796, which facilitated access to northern areas previously dominated by dense forests and wetlands.[12] The first documented European settler in the northern York Township area was Scottish immigrant Andrew McGlashan, who constructed a log cabin east of Bayview Avenue and north of York Mills Road in 1804; he later established North York's inaugural tannery in Hogg's Hollow in 1815, supporting early agricultural and small-scale industrial activities.[12] Initial settlement from around 1795 onward focused on farming, with pioneers clearing land for mixed agriculture amid challenging terrain, as the broader York Township—surveyed in 1793—remained predominantly rural until the 20th century, contrasting with urban growth nearer Lake Ontario.[13] By the early 1900s, the northern portion of York Township housed about 6,000 farmers who contributed 23% of the municipality's taxes yet lacked representation on a council prioritizing southern urban infrastructure like sidewalks and waterworks.[3] In 1921, a committee was formed to segregate the rural north from the urbanizing south, bolstered by the provincial Farmers' Party's electoral success, leading to North York's secession.[12] The Township of North York was officially incorporated on June 13, 1922, with its first five-member council—entirely farmers—elected on August 12, 1922, under reeve R.F. Hicks; initial meetings occurred at Brown School before relocating to the Golden Lion Hotel.[3]Post-War Suburban Expansion

Following World War II, North York experienced a housing shortage that spurred rapid suburban development as Toronto's metropolitan area expanded northward into former farmland. Developers capitalized on the post-war baby boom and influx of residents seeking affordable single-family homes, transforming the township from predominantly rural to a burgeoning commuter suburb by the late 1940s and 1950s.[14][5] A pivotal project was Don Mills, initiated in the late 1940s when industrialist E.P. Taylor assembled farmland north and east of Toronto for planned community development. Construction began in the early 1950s under the direction of planner Macklin Hancock, creating Canada's first self-contained suburb with integrated residential, industrial, and commercial zones modeled on garden city principles to promote balanced growth and reduce urban sprawl dependency. By the mid-1960s, Don Mills featured diverse housing types, including single-detached homes and early apartment complexes, alongside employment hubs that attracted middle-class families.[14][15][16] Complementary developments included Flemingdon Park, another early planned suburb built in the 1950s as a complete neighborhood with housing and industry, marking some of North America's first privately developed suburban apartment areas in the late 1950s. Shopping infrastructure emerged to serve the growing populace, exemplified by Lawrence Plaza, Toronto's inaugural suburban shopping centre, which opened on November 13, 1953, and anchored retail expansion along arterial roads like Yonge Street.[15][17][18] Transportation improvements facilitated this outward growth, with the construction of Highway 401 through North York in the 1950s providing high-speed access to downtown Toronto and enabling automobile-dependent commuting patterns. Population growth accelerated dramatically starting in the 1950s, as developers built thousands of new homes and amenities, shifting North York from agricultural roots to a mosaic of low-density suburbs by the 1960s.[19][5]Path to City Status and Borough Development

The Township of North York, established on July 18, 1922, by secession from the larger York Township to address local governance needs amid rural-suburban tensions, transitioned to borough status on January 1, 1967.[20][4] This change, part of broader Metropolitan Toronto reforms, granted the reeve full mayoral powers and enhanced local planning authority, reflecting post-war population surges that necessitated more responsive administration.[21] As a borough, North York pursued rapid infrastructure and commercial development under the leadership of figures like Mel Lastman, who was elected mayor in 1973 and served until 1997.[7] Lastman's tenure emphasized suburban expansion, including the cultivation of North York Centre as a civic and economic hub, with investments in roads, schools, and retail to accommodate growing residential densities driven by immigration and affordable housing demand.[7] These efforts capitalized on Metro Toronto's coordinated services while asserting borough-level autonomy, fostering a shift from agrarian roots to a burgeoning urban-suburban entity.[22] The push for full city status culminated on February 14, 1979, when provincial legislation elevated North York to incorporate as a city, providing greater fiscal and legislative independence amid a population exceeding 500,000 by the late 1970s.[4][13] This status symbolized the culmination of decades of advocacy for self-determination, justified by empirical metrics of growth and economic vitality, though it operated within Metro Toronto's framework until amalgamation in 1998.[23] Lastman's pro-development policies, including streamlined zoning and public-private partnerships, were instrumental in this progression, enabling North York to rival older municipalities in service delivery and urban form.[7]Amalgamation with Toronto: Process and Immediate Effects

In December 1996, the Ontario government under Premier Mike Harris introduced Bill 103, the City of Toronto Act, 1997, which mandated the amalgamation of Metropolitan Toronto and its six lower-tier municipalities—including North York—into a single City of Toronto effective January 1, 1998.[24][25] The legislation passed on April 23, 1997, despite widespread opposition from the affected municipalities, where referendums in March 1997 recorded approximately 75% votes against amalgamation among those who participated (with 33% turnout).[26][25] North York's mayor, Mel Lastman, vocally protested the move, arguing it would erase the suburb's distinct identity and autonomy, though he later entered the mayoral race for the new city.[25][1] The provincial government appointed a transition board to oversee the merger, handling initial administrative integration until the first municipal election on November 10, 1997, which selected the new city's council and mayor.[25] Lastman won the mayoralty, securing 57% of the vote and becoming the first leader of the amalgamated Toronto, with strong support from suburban voters including those in North York.[27][1] The new council consisted of 57 members (one mayor and 56 councillors), a reduction from the pre-amalgamation total of over 100 across the entities, aiming for streamlined decision-making.[28] This shift dissolved North York's independent borough council, folding its operations into the unified structure. Immediate effects included significant transition costs estimated at $150 to $220 million for severance, redundancies, and administrative harmonization, alongside the province's downloading of responsibilities like social services, adding an annual burden of about $202 million to the new city.[29][25] Promised annual savings of $230 to $364 million by 2000 failed to materialize, with studies indicating no net fiscal efficiencies and an increase in the overall wage bill due to service equalization.[29][28] For North York residents, amalgamation led to the loss of tailored suburban services and lower tax rates, prompting fears of hikes to match core Toronto's higher standards, though Lastman's election mitigated some suburban discontent by prioritizing regional balance.[25] Governance disruptions arose from merging disparate bureaucracies, exacerbating tensions between former suburban and urban areas without immediate improvements in service delivery.[28]Geography

Boundaries and Topography

North York forms the northern district of the City of Toronto, with its northern boundary defined by Steeles Avenue, which separates it from the Regional Municipality of York, including the cities of Vaughan to the northwest and Markham to the northeast.[30] The western limit follows the Humber River, bordering the adjacent Etobicoke district within Toronto.[31] To the east, the boundary runs along Victoria Park Avenue for much of its length, with variations incorporating the Don River valley.[31] The southern boundary is irregular, reflecting pre-1998 municipal lines: it generally follows Eglinton Avenue West in the west, extends northward along Sheppard and Wilson Avenues centrally, and aligns with Lawrence Avenue East in the east, demarcating the former divide from the old City of Toronto.[32] The district encompasses approximately 177 square kilometres, as defined by the former City of North York prior to its amalgamation into Toronto on January 1, 1998.[32] This configuration positions North York as a transitional zone between the dense urban core of downtown Toronto to the south and the more rural-suburban expanse of York Region to the north. Topographically, North York lies on a glacial till plain with elevations averaging 178 meters above sea level, ranging from roughly 150 to 220 meters.[33] The terrain is predominantly flat to gently undulating, shaped by post-glacial drainage patterns, but features significant local relief due to entrenched river valleys. The Humber River in the west and the Don River in the east have carved deep ravines, often exceeding 30 meters in depth, which serve as natural green corridors amid urban development.[34] These valleylands contrast with the elevated plateaus supporting residential and commercial suburbs, contributing to varied microclimates and opportunities for recreational trails. Minimal steep slopes characterize the area, aligning with the broader low-relief physiography of the Toronto region.[35]Neighbourhoods and Urban Form

North York's urban form is characterized by a blend of post-war suburban residential areas and targeted high-density developments along transit corridors, reflecting phased growth from rural township to integrated urban district. Much of the district features low-density single-family homes built between the 1950s and 1970s on curvilinear streets amid green spaces and ravines, with densities typically averaging 10-20 units per hectare in peripheral zones.[36] Intensification since the 1980s has concentrated around subway stations on Line 1 Yonge-University, fostering mid- and high-rise clusters exceeding 20 storeys in areas like Willowdale and North York Centre.[37] The North York Centre, spanning Yonge Street from Finch Avenue to Sheppard Avenue West, exemplifies this evolution as a designated growth hub with mixed-use towers, civic buildings, and retail, supported by rapid transit access that has driven population densities over 100 residents per hectare.[37] This corridor-based densification contrasts with broader suburban patterns, where commercial strips along arterial roads like Steeles Avenue and Highway 7 complement low-rise housing estates.[38] Planned communities, such as Don Mills developed from 1954 onward, introduced garden suburb principles with integrated offices, schools, and parks on 2,200 acres, influencing subsequent neighbourhood designs.[39] North York comprises about 25 of Toronto's 158 official neighbourhoods, each exhibiting distinct morphologies shaped by topography, immigration, and zoning.[40] Western areas like Downsview feature aviation heritage sites repurposed into residential parks and light industry, with row housing and estates on former military lands.[41] Eastern enclaves such as Flemingdon Park consist of 1960s concrete high-rise towers housing diverse renters, averaging 15-20 storeys amid open greenways.[42] Central zones like Willowdale blend high-rise condos with walk-up apartments, accommodating high immigrant densities along Yonge Street's commercial spine.[43] Upscale suburbs in the northeast, including Bayview Village and York Mills, maintain low-density estates with custom homes on large lots, anchored by village-style shopping plazas.[42] These variations underscore North York's polycentric structure, balancing suburban livability with urban vitality through corridor-focused growth policies.[37]Climate

Seasonal Patterns and Data

North York exhibits a humid continental climate characterized by four distinct seasons, with cold winters moderated somewhat by Lake Ontario, warm humid summers, transitional springs and autumns, and relatively even precipitation distribution year-round. Winters (December to February) feature average high temperatures ranging from -1°C to 2°C and lows from -10°C to -6°C, with frequent snowfall and occasional lake-effect snow enhancing variability. Summers (June to August) bring average highs of 23°C to 26°C and lows around 15°C to 18°C, accompanied by high humidity and convective thunderstorms. Spring and fall serve as mild transition periods, with increasing daylight and foliage changes in autumn contributing to scenic patterns, though frost risks persist into late spring. Climate data for North York align closely with Toronto Pearson International Airport normals (1991-2020), located within the district's vicinity, reflecting slightly cooler conditions than downtown Toronto due to reduced urban heat island effects and greater distance from the lake. Annual mean temperature stands at 9.1°C, with total precipitation averaging 830 mm and snowfall accumulating to 108.5 cm seasonally. Extreme events include occasional polar vortex intrusions yielding temperatures below -20°C in winter and heat waves exceeding 30°C in summer, occurring on average seven days annually city-wide.[44][45][46] The following table summarizes monthly climate normals derived from Environment and Climate Change Canada data for the Toronto area, applicable to North York:| Month | Mean Temperature (°C) | Precipitation (mm) | Snowfall (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | -4.1 | 44.0 | 19.5 |

| February | -3.2 | 39.7 | 18.7 |

| March | 0.9 | 46.6 | 13.5 |

| April | 7.8 | 66.9 | 2.1 |

| May | 13.8 | 81.5 | 0.1 |

| June | 19.1 | 71.8 | 0.0 |

| July | 21.9 | 77.6 | 0.0 |

| August | 21.4 | 82.7 | 0.0 |

| September | 17.5 | 75.3 | 0.0 |

| October | 11.1 | 68.4 | 1.1 |

| November | 4.8 | 68.3 | 7.6 |

| December | -1.1 | 51.0 | 16.0 |

Impacts on Development and Livability

North York's humid continental climate, characterized by cold, snowy winters and warm, humid summers, has profoundly influenced urban development patterns, favoring low-density suburban sprawl post-World War II to accommodate car-dependent commuting amid frequent winter storms and icy roads. Infrastructure investments in snow removal, heated sidewalks in commercial hubs like North York Centre, and elevated roadways have been essential to mitigate seasonal disruptions, with the City of Toronto allocating millions annually for plowing operations that extend into North York's grid-like street network. This climate-driven emphasis on vehicular mobility contributed to expansive residential subdivisions in areas like Don Mills and Flemingdon Park, where single-family homes with garages predominated to shield residents from harsh weather, though it has since complicated densification efforts under modern zoning reforms.[49][50] Extreme precipitation events, exacerbated by climate change, pose ongoing risks to development, as evidenced by the July 2021 floods that caused over $800 million in regional damages, including basement inundations and sewer overflows in North York's low-lying neighborhoods near the Don River. These incidents have prompted adaptive measures such as low-impact development techniques, including permeable pavements and rain gardens in new builds, to manage stormwater runoff in a region where annual precipitation averages 800-900 mm but is increasingly concentrated in intense bursts. Urban heat island effects amplify summer temperatures by 2-5°C in paved commercial corridors like Yonge Street, driving planning requirements for green roofs and tree canopies in recent high-rise approvals to reduce heat stress during events that have risen from 5-10 days above 30°C historically to projections of 20+ by mid-century.[49][51][52] On livability, the climate supports high quality-of-life indices through distinct seasons enabling winter recreation like skating on outdoor rinks and extended summer patios, yet vulnerabilities persist for residents without air conditioning—estimated at 20-30% in older rental stock—during heat waves that have correlated with spikes in heat-related hospitalizations, particularly among seniors and low-income households in North York. Vector-borne diseases, such as West Nile virus carried by mosquitoes thriving in humid conditions, have prompted public health campaigns and larviciding in stagnant water pools post-rainfall, while milder winters may extend tick activity seasons, raising Lyme disease risks in greenbelt-adjacent areas. Overall, these factors underscore a trade-off: the temperate baseline fosters outdoor-oriented communities, but intensifying extremes necessitate resilient design to sustain North York's appeal as a family-friendly suburb amid Toronto's urban pressures.[53][54][50]Demographics

Population Growth and Trends

North York's population expanded dramatically during the mid-20th century amid post-war suburbanization, increasing from 170,110 residents in the 1961 census to 556,297 by 1991, fueled by affordable single-family housing, improved road infrastructure like Highway 401, and proximity to central Toronto's employment centers.[55] This growth reflected broader patterns of white-collar migration to outer municipalities, with annual rates often exceeding 5% in the 1960s and 1970s as farmland converted to residential subdivisions.[5] After amalgamation into Toronto in 1998, growth moderated as available greenfield land diminished and urban policies emphasized intensification over sprawl. The district recorded 639,900 residents in 2006 and 667,840 in 2011, a 4.4% rise over the period, before a corrected count of 638,090 in 2016 indicated temporary stagnation possibly due to census adjustments or out-migration amid rising housing costs.[56] By 2021, the population reached 647,245, marking a modest 1.4% increase from 2016, lower than Toronto's overall 2.3% growth rate and attributable to immigration-driven infill in high-rises along Yonge Street and subway corridors rather than expansive development.[57] These trends highlight a shift from high-volume suburban accretion to slower, density-focused expansion, with the 2021 age distribution showing 17.8% seniors (65+), up from prior decades, signaling aging demographics amid limited family-oriented housing additions.[57] Projections from provincial sources suggest continued low single-digit growth through 2030, constrained by land scarcity and fiscal pressures on infrastructure.[58]Ethnic and Cultural Composition

North York exhibits significant ethnic and cultural diversity, with immigrants comprising 51.7% of its 647,245 residents as of the 2021 Census.[57] This reflects post-World War II European immigration followed by waves from Asia, the Middle East, and the Philippines, contributing to a visible minority population of 372,695 persons or 57.6% of the total.[57] The largest visible minority groups include Chinese at 91,310 (14.1%), South Asian at 64,075 (9.9%), Filipino at 57,085 (8.8%), and Black at 37,475 (5.8%).[57] Self-reported ethnic or cultural origins, which permit multiple responses and thus exceed 100% of the population, highlight the following top groups:| Ethnic or Cultural Origin | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 87,170 | 9.7% |

| Filipino | 52,795 | 5.9% |

| English | 42,860 | 4.8% |

| Jewish | 36,755 | 4.1% |

| Italian | 36,175 | 4.0% |

| Irish | 35,905 | 4.0% |

| Indian (India) | 35,450 | 4.0% |

| Scottish | 35,085 | 3.9% |

| Canadian | 33,710 | 3.8% |

| Iranian | 24,330 | 2.7% |

Socioeconomic Metrics and Immigration Effects

In 2021, North York's median total household income stood at $84,000 for the 2020 reference year, aligning closely with the $84,000 median for the City of Toronto overall.[57] Average household income in the district was $86,000, with 14.8% of households earning $200,000 or more and 13.5% classified as low-income under the after-tax Low-Income Measure (LIM-AT).[57] Labour force participation among those aged 15 and over was 62.3%, yielding an unemployment rate of 13.4%, elevated amid 2021's COVID-19 recovery phase.[57] Educational attainment reached 46.5% for university certificates, diplomas, or degrees at the bachelor's level or above among the population aged 15 and older, supporting skilled employment in sectors like professional services and technology.[57] Immigrants comprised 51.7% of North York's population in 2021, exceeding the 46.6% rate in the broader Toronto CMA, with recent arrivals (2016–2021) accounting for 8.9% or 59,340 individuals, predominantly from the Philippines (20.2% of recent immigrants), India (15.0%), and China (10.1%).[57] [59] This demographic influx has bolstered labour force growth and cultural diversity, yet empirical analyses link high immigration levels to intensified housing demand and price escalation in Toronto municipalities, including North York, where non-permanent residents and newcomers amplify affordability pressures from 2006–2021.[60] Recent immigrants often experience initial income gaps relative to Canadian-born residents, contributing to observed rises in family income inequality, as up to half of early-1990s increases in Canada stemmed from such disparities, a pattern persisting in immigrant-heavy areas like North York.[61] [62] Over time, however, immigrant integration via education and employment mitigates these effects, with North York's metrics reflecting a net positive on overall socioeconomic vitality despite short-term strains on public services and wage competition in low-skill sectors.[63]Government and Politics

Pre-Amalgamation Governance Structures

The Township of North York was incorporated on July 18, 1922, from the northern portion of York Township in York County, Ontario, initially governing a sparsely populated rural area with under 6,000 residents.[64][65] As a township, its governance structure followed Ontario's municipal framework for rural areas, led by a reeve elected at-large and supported by ward-based councillors responsible for basic local services including road maintenance, fire protection, and minor bylaws.[65] Rapid post-World War II suburban development, driven by residential expansion and highway construction, prompted North York's elevation to borough status on February 14, 1967, aligning it with urbanizing peers in the newly formed Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto (established 1954).[64] Borough incorporation expanded its powers to include zoning, building permits, and local utilities, while the head of council shifted from reeve to mayor.[4] The council comprised a mayor and controllers elected municipality-wide, plus aldermen from wards, with all members serving three-year terms; this at-large and ward hybrid aimed to balance executive leadership with localized representation.[20] North York achieved city status on February 10, 1979, amid population growth surpassing 400,000, conferring symbolic autonomy and enhanced borrowing capacity but retaining its lower-tier role under Metro Toronto's two-level system.[64] The city council maintained the borough's structural model, overseeing services like parks, libraries, and waste management, while deferring regional functions—such as major roads, public transit via the TTC, and policing—to Metro Council, where North York's mayor and select aldermen held seats.[65] This setup preserved significant local decision-making until the 1998 amalgamation dissolved independent governance.[28]Amalgamation Controversies and Local Autonomy Loss

The amalgamation of North York into the City of Toronto was legislated by the Ontario Progressive Conservative government under Premier Mike Harris through Bill 103, the City of Toronto Act, passed on April 16, 1997, and effective January 1, 1998, merging the six municipalities of Metropolitan Toronto—including North York, Etobicoke, Scarborough, York, East York, and the City of Toronto—into a single entity with a population exceeding 2.3 million.[66] This provincial override dissolved North York's independent borough status, which it had held since its elevation from township to borough in 1967, eliminating its dedicated council of 24 members and mayor responsible for local bylaws, zoning, and services tailored to its suburban character.[29] The move was part of Harris's "Common Sense Revolution" platform, aimed at reducing government layers and downloading social services to municipalities to enable provincial tax cuts, but it provoked immediate backlash for circumventing local democratic processes.[67] North York's leadership, led by long-serving Mayor Mel Lastman, vocally opposed the forced merger, arguing it would erode local autonomy and impose downtown-centric policies on suburban areas with divergent needs, such as lower-density housing and commercial strips along Yonge Street.[68] Lastman and other suburban mayors contended that Metro Toronto's existing two-tier structure already coordinated regional services like transit and water while preserving municipal control over parks, libraries, and waste collection, allowing North York to maintain lower property taxes—averaging 1.2% of assessed value pre-amalgamation compared to higher rates in the old City of Toronto.[69] Public opposition manifested in non-binding referendums across affected areas, where over 70% of voters in some suburbs rejected amalgamation, yet the province dismissed these as advisory and proceeded unilaterally, sparking protests and legal challenges that failed to halt the process.[70] Critics, including local business groups, warned of service disruptions and fiscal burdens, as North York's efficient administration—handling a population of about 600,000 with streamlined operations—would be subsumed into a larger bureaucracy. Post-amalgamation, North York residents experienced tangible loss of local autonomy, with decision-making centralized under a 57-member city council where suburban wards, including North York's six, often found their priorities diluted by the 22 wards from the former core city, leading to policies favoring urban intensification over suburban maintenance.[28] While "community councils" were created for former borough areas like North York to advise on local matters, their authority remained subordinate to the unified council, lacking veto power over zoning or budgets, which contrasted with pre-1998 borough councils' direct oversight.[71] Empirical assessments revealed no promised economies of scale; a 2002 provincial review and subsequent studies documented higher per capita administrative costs—rising from $200 to over $250 per resident by 2008—and increased property taxes in suburbs by up to 20% to harmonize services, as North York's lower rates were equalized upward without offsetting efficiencies.[10] This centralization exacerbated governance inefficiencies, with North York's distinct needs, such as expanded road networks for commuter traffic, receiving less tailored attention amid city-wide priorities, fostering ongoing suburban discontent and calls for devolution.[72] Proponents' claims of streamlined delivery were undermined by data showing debt accumulation and service delays, attributing failures to the top-down structure rather than inherent suburban-city divides.[9]Current Political Representation and Fiscal Implications

North York, as a district within the amalgamated City of Toronto, is represented municipally by city councillors elected to wards that encompass its boundaries, primarily Wards 6 (York Centre), 7 (Humber River–Black Creek), 8 (Eglinton–Lawrence), 16 (Don Valley East), 17 (Don Valley North), 18 (Willowdale), 20 (Willowdale), 21 (Bayview Village? Wait, standard wards 6-8,16-18,23? From data: key wards include 6 (James Pasternak), 7 (Anthony Perruzza), 16 (Jon Burnside), 17 (Shelley Carroll), 18 (Lily Cheng). [73] These wards fall under the North York Community Council, which advises on local planning and services but lacks independent decision-making authority. At the provincial level, North York spans several Ontario electoral districts, including Willowdale, Don Valley North, Don Valley East, York Centre, Humber River–Black Creek, and Eglinton–Lawrence, each electing one Member of Provincial Parliament (MPP) to the Legislative Assembly. [74] As of 2025, these ridings are held by MPPs from the Progressive Conservative and New Democratic parties, reflecting suburban voter preferences for fiscal conservatism and infrastructure priorities. [75] Federally, the area is covered by ridings such as Don Valley North, Don Valley West, Willowdale, York Centre, and Humber River–Black Creek, with Members of Parliament (MPs) elected to the House of Commons. [76] These representations prioritize issues like transit expansion and housing affordability, though suburban ridings often advocate for reduced urban-centric spending. The 1998 amalgamation eliminated North York's separate fiscal autonomy, integrating its budget into Toronto's unified $18.8 billion operating budget for 2025, which funds city-wide services without district-specific allocations. [77] Pre-amalgamation, North York maintained lower property tax rates—around 1.5-2% of assessed value compared to Toronto's higher core rates—allowing tailored spending on suburban infrastructure. [78] Post-amalgamation, taxes harmonized upward, with empirical analyses showing per-household property tax increases of 20-30% in former suburban municipalities like North York to subsidize downtown services, without corresponding cost savings from consolidation. [79] [80] This shift contributed to long-term debt growth and employee compensation rises exceeding inflation, as local revenues now support centralized administration. [79] In 2025, Toronto imposed a uniform 6.9% residential property tax hike (5.4% base plus 1.5% for capital), straining North York's middle-class homeowners amid stagnant per-capita service delivery in outer areas. [81] Critics, including independent fiscal reviews, attribute ongoing suburban dissatisfaction to this structure, where wealthier North York assessments cross-subsidize underfunded core infrastructure without voter-approved referenda. [82]Economy

Major Sectors and Employment Hubs

North York's economy is dominated by office-based sectors, including professional, scientific, and technical services; finance and insurance; and public administration, alongside substantial retail and institutional employment in healthcare and education. The district hosts 311,900 jobs, representing 19.5% of Toronto's citywide total as of the 2024 Toronto Employment Survey, with the highest share of retail jobs among districts at 26.3%.[83] Institutional sectors, encompassing hospitals and universities, provide stable employment amid fluctuations in office roles influenced by remote work trends.[84] The North York Centre serves as the district's principal employment hub, concentrating 35,600 jobs or 11.4% of the district's total, with a 2.4% year-over-year increase to 2024 despite a net decline from pre-pandemic levels. Office employment dominates at 77.6% (27,640 jobs), supported by subsectors such as public administration (21.3% of office jobs), professional and technical services (19.8%), and finance and insurance (17.7%) as of 2022 data.[83][84] Service sector jobs account for 8.8% (3,130 positions), reflecting growth in personal and business services, while institutional roles grew 12.1% annually to 2,320 jobs, driven by healthcare and educational institutions. Retail contributes 4.7% (1,670 jobs), concentrated in malls and commercial strips, though it experienced minor contraction. Manufacturing and warehousing remain marginal at 0.2%.[83]| Land Use Activity Class | Jobs (2024) | Share (%) | YoY Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Office | 27,640 | 77.6 | +2.6% |

| Service | 3,130 | 8.8 | -1.6% |

| Institutional | 2,320 | 6.5 | +12.1% |

| Retail | 1,670 | 4.7 | -1.8% |

| Community & Entertainment | 770 | 2.2 | -4.9% |

| Manufacturing & Warehousing | 70 | 0.2 | 0% |

Post-Amalgamation Economic Shifts