Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Object-oriented analysis and design

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Software development |

|---|

Object-oriented analysis and design (OOAD) is an approach to analyzing and designing a computer-based system by applying an object-oriented mindset and using visual modeling throughout the software development process. It consists of object-oriented analysis (OOA) and object-oriented design (OOD) – each producing a model of the system via object-oriented modeling (OOM). Proponents contend that the models should be continuously refined and evolved, in an iterative process, driven by key factors like risk and business value.

OOAD is a method of analysis and design that leverages object-oriented principals of decomposition and of notations for depicting logical, physical, state-based and dynamic models of a system. As part of the software development life cycle OOAD pertains to two early stages: often called requirement analysis and design.[1]

Although OOAD could be employed in a waterfall methodology where the life cycle stages as sequential with rigid boundaries between them, OOAD often involves more iterative approaches. Iterative methodologies were devised to add flexibility to the development process. Instead of working on each life cycle stage at a time, with an iterative approach, work can progress on analysis, design and coding at the same time. And unlike a waterfall mentality that a change to an earlier life cycle stage is a failure, an iterative approach admits that such changes are normal in the course of a knowledge-intensive process – that things like analysis can't really be completely understood without understanding design issues, that coding issues can affect design, that testing can yield information about how the code or even the design should be modified, etc.[2] Although it is possible to do object-oriented development in a waterfall methodology, most OOAD follows an iterative approach.

The object-oriented paradigm emphasizes modularity and re-usability. The goal of an object-oriented approach is to satisfy the "open–closed principle". A module is open if it supports extension, or if the module provides standardized ways to add new behaviors or describe new states. In the object-oriented paradigm this is often accomplished by creating a new subclass of an existing class. A module is closed if it has a well defined stable interface that all other modules must use and that limits the interaction and potential errors that can be introduced into one module by changes in another. In the object-oriented paradigm this is accomplished by defining methods that invoke services on objects. Methods can be either public or private, i.e., certain behaviors that are unique to the object are not exposed to other objects. This reduces a source of many common errors in computer programming.[3]

Object-oriented analysis

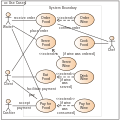

[edit]Common models used in OOA are the use case and the object model. A use case describes a scenario for standard domain functions that the system must accomplish. An object model describes the names, class relations, operations, and properties of the main objects. User-interface mockups or prototypes can also be created to help understanding.[4]

Unlike with OOA that organizes requirements around objects that integrate processes and data, with other analysis methods, processes and data are considered separately. For example, data may be modeled by entity–relationship diagrams, and behaviors by flowcharts or structure charts.

Artifacts

[edit]Outputs of OOA are inputs to OOD. In an iterative approach, and an output artifact does not need to be completely developed to serve as input to OOD. Both OOA and OOD can be performed incrementally, and the artifacts can be continuously grown instead of completely developed in one shot. OOA artifacts include:

- Conceptual model

- A conceptual model captures concepts in the problem domain. The conceptual model is explicitly chosen to be independent of implementation details, such as concurrency or data storage.

- Use case

- A use case is a description of sequences of events that lead to a system doing something useful. Each use case provides one or more scenarios that convey how the system should interact with the users called actors to achieve a specific business goal or function. Use case actors may be end users or other systems. In many circumstances use cases are further elaborated into use case diagrams. Use case diagrams are used to identify the actor (users or other systems) and the processes they perform.

- System sequence diagram

- A system sequence diagram (SSD) is a picture that shows, for a particular scenario of a use case, the events that external actors generate, their order, and possible inter-system events.

- User interface documentation

- Optional documentation that shows and describes the look and feel of the user interface.

- Relational data model

- If an object database is not used, a relational data model should usually be created before the design since the strategy chosen for object–relational mapping is an output of the OO design process. However, it is possible to develop the relational data model and the OOD artifacts in parallel, and the growth of an artifact can stimulate the refinement of other artifacts.

Object-oriented design

[edit]OOD, a form of software design, is the process of planning a system of interacting objects to solve a software problem. A designer applies implementation constraints to the conceptual model produced in OOA. Such constraints could include the hardware and software platforms, the performance requirements, persistent storage and transaction, usability of the system, and limitations imposed by budgets and time. Concepts in the analysis model which is technology independent, are mapped onto implementing classes and interfaces resulting in a model of the solution domain, i.e., a detailed description of how the system is to be built on concrete technologies.[5]

OOD activities include:

- Defining objects and their attributes

- Creating class diagrams from conceptual models

- Using design patterns[6]

- Defining application frameworks

- Identifying persistent objects/data

- Designing the object relation mapping if a relational database is used

- Identifying remote objects

OOD principles and strategies include:

- Dependency injection

- Dependency injection is that if an object depends upon having an instance of some other object then the needed object is "injected" into the dependent object; for example, being passed a database connection as an argument to the constructor instead of creating one internally.

- Acyclic dependencies principle

- The acyclic dependencies principle is that dependency graph of packages or components (the granularity depends on the scope of work for one developer) should have no cycles. This is also referred to as having a directed acyclic graph.[7] For example, package C depends on package B, which depends on package A. If package A depended on package C, you would have a cycle.

- Composite reuse principle

- The composite reuse principle is to favor polymorphic composition of objects over inheritance.[6]

Artifacts

[edit]- Sequence diagram

- Extend the sequence diagram to add specific objects that handle the system events. A sequence diagram shows, as parallel vertical lines, different processes or objects that live simultaneously, and, as horizontal arrows, the messages exchanged between them, in the order in which they occur.

- Class diagram

- A class diagram is a type of static structure UML diagram that describes the structure of a system by showing the system's classes, its attributes, and the relationships between the classes. The messages and classes identified through the development of the sequence diagrams can serve as input to the automatic generation of the global class diagram of the system.

See also

[edit]- ATLAS Transformation Language

- Class-responsibility-collaboration card

- Domain specific language

- Domain-driven design

- Domain-specific modelling

- GRASP (object-oriented design)

- IDEF4

- Meta-Object Facility

- Metamodeling

- Model-driven engineering

- Model-based testing

- Object-oriented modeling

- Object-oriented user interface

- QVT

- Shlaer–Mellor method

- Software analysis pattern

- SOLID

- Story-driven modeling

- Unified Process

References

[edit]- ^ Jacobsen, Ivar; Magnus Christerson; Patrik Jonsson; Gunnar Overgaard (1992). Object Oriented Software Engineering. Addison-Wesley ACM Press. pp. 15, 199. ISBN 0-201-54435-0.

- ^ Boehm B, "A Spiral Model of Software Development and Enhancement Archived 2015-05-28 at the Wayback Machine", IEEE Computer, IEEE, 21(5):61-72, May 1988

- ^ Meyer, Bertrand (1988). Object-Oriented Software Construction. Cambridge: Prentise Hall International Series in Computer Science. p. 23. ISBN 0-13-629049-3.

- ^ Jacobsen, Ivar; Magnus Christerson; Patrik Jonsson; Gunnar Overgaard (1992). Object Oriented Software Engineering. Addison-Wesley ACM Press. pp. 77–79. ISBN 0-201-54435-0.

- ^ Conallen, Jim (2000). Building Web Applications with UML. Addison Wesley. p. 147. ISBN 0201615770.

- ^ a b Erich Gamma; Richard Helm; Ralph Johnson; John Vlissides (January 2, 1995). Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-201-63361-0.

- ^ "What Is Object-Oriented Design?". Object Mentor. Archived from the original on 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

Further reading

[edit]- Grady Booch. "Object-oriented Analysis and Design with Applications, 3rd edition":http://www.informit.com/store/product.aspx?isbn=020189551X Addison-Wesley 2007.

- Rebecca Wirfs-Brock, Brian Wilkerson, Lauren Wiener. Designing Object Oriented Software. Prentice Hall, 1990. [A down-to-earth introduction to the object-oriented programming and design.]

- A Theory of Object-Oriented Design: The building-blocks of OOD and notations for representing them (with focus on design patterns.)

- Martin Fowler. Analysis Patterns: Reusable Object Models. Addison-Wesley, 1997. [An introduction to object-oriented analysis with conceptual models]

- Bertrand Meyer. Object-oriented software construction. Prentice Hall, 1997

- Craig Larman. Applying UML and Patterns – Introduction to OOA/D & Iterative Development. Prentice Hall PTR, 3rd ed. 2005.

- Setrag Khoshafian. Object Orientation.

- Ulrich Norbisrath, Albert Zündorf, Ruben Jubeh. Story Driven Modeling. Amazon Createspace. p. 333, 2013. ISBN 9781483949253.

External links

[edit]- Article Object-Oriented Analysis and Design with UML and RUP an overview (also about CRC cards).

- Applying UML – Object Oriented Analysis & Design Archived 2009-09-15 at the Wayback Machine tutorial

- OOAD & UML Resource website and Forums – Object Oriented Analysis & Design with UML

- Software Requirement Analysis using UML article by Dhiraj Shetty

- Article Object-Oriented Analysis in the Real World

- Object-Oriented Analysis & Design – overview using UML

- Larman, Craig. Applying UML and Patterns – Third Edition

- Object-Oriented Analysis and Design

- LePUS3 and Class-Z: formal modelling languages for object-oriented design

- The Hierarchy of Objects

Object-oriented analysis and design

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Scope

Object-oriented analysis and design (OOAD) is a software engineering methodology that applies object-oriented principles to the analysis and design phases of software development, modeling real-world entities as objects with encapsulated data and behaviors to represent the problem domain and system structure.[5] This approach emphasizes decomposing complex systems into collaborative objects, facilitating a more intuitive mapping between user requirements and software artifacts. The scope of OOAD encompasses the transition from understanding the problem domain to creating implementable system blueprints, focusing exclusively on pre-coding stages without extending to implementation, testing, or deployment.[5] It delineates two core phases: object-oriented analysis, which investigates requirements from the perspective of classes and objects in the problem domain to define what the system must do; and object-oriented design, which details how the system achieves these functions through object decomposition, interactions, and notations for logical, physical, static, and dynamic models. In analysis, the emphasis is on capturing functional and non-functional needs via domain modeling, whereas design refines these into architectural and detailed specifications for realization.[6] OOAD serves as the foundational paradigm for object-oriented programming (OOP), providing the conceptual models that guide code implementation, but remains distinct by prioritizing high-level abstraction over language-specific coding.[5] Principles such as encapsulation and inheritance, central to OOAD, enable modular and reusable designs that align closely with real-world complexities.Historical Development

The origins of object-oriented analysis and design (OOAD) trace back to the mid-1960s with the development of the Simula programming language by Kristen Nygaard and Ole-Johan Dahl at the Norwegian Computing Center. Released in 1967, Simula introduced classes and objects as core constructs for simulation modeling, establishing foundational concepts like encapsulation and inheritance that later underpinned OOAD methodologies.[7][8] The 1970s marked a pivotal shift toward fully object-oriented systems with the creation of Smalltalk by Alan Kay and colleagues at Xerox PARC, first implemented in 1972. Smalltalk emphasized messages between objects and dynamic behavior, promoting a paradigm change from procedural programming to object-centric thinking that influenced subsequent OOAD practices in the 1980s.[9] During this period, Grady Booch advanced object-oriented design (OOD) through his methodological contributions, including the 1980s paper that coined the term and outlined graphical notations for object-based software architecture.[10] The formalization of object-oriented analysis (OOA) followed in 1991 with Peter Coad and Edward Yourdon's book, which provided structured techniques for identifying and modeling objects during requirements analysis.[11] The 1990s brought standardization to OOAD through the Unified Modeling Language (UML), developed collaboratively by Grady Booch, Ivar Jacobson, and James Rumbaugh starting in 1994 at Rational Software. UML 1.0 was adopted by the Object Management Group (OMG) in 1997, offering a unified notation for visualizing, specifying, and documenting object-oriented systems.[12] From the 2000s onward, OOAD evolved by integrating with agile methodologies after the 2001 Agile Manifesto, enabling iterative object modeling in flexible development processes.[13] Adaptations for modern paradigms, such as microservices, have involved applying OOAD principles like modularity and encapsulation to distributed systems, often contrasting object-oriented approaches with event-oriented ones for service decomposition.[14] Post-2010, refinements have focused on enhanced tool support, including updates to UML versions like 2.5 in 2015, which improved diagram precision and integration without introducing major paradigm shifts.[15]Core Principles

Fundamental Concepts

Object-oriented analysis and design (OOAD) relies on several foundational concepts that enable the modeling of complex systems through objects and their interactions. These principles—abstraction, encapsulation, inheritance, and polymorphism—form the core of object-oriented thinking, allowing analysts and designers to represent real-world entities and their behaviors in a structured, reusable manner. Additionally, relationships such as association, aggregation, and composition define how objects connect, providing the structural glue for robust designs. Abstraction simplifies complex systems by focusing on essential features while hiding irrelevant details, thereby creating conceptual boundaries that reflect the problem domain's vocabulary. In OOAD, it involves identifying key properties, roles, and behaviors of objects, often elevating common characteristics to higher-level classes, such as a generic KnowledgeSource class that encompasses various information providers. This process aids in managing complexity by separating what an object does from how it does it, ensuring models remain platform-independent and focused on essentials. Encapsulation bundles an object's data and methods into a single unit, protecting its internal state and promoting modularity by exposing only a well-defined interface. This separation of interface from implementation allows changes to internal details without affecting external code, enhancing maintainability and security; for instance, an LCD Device class might hide its hardware specifics while providing standard display operations. In analysis and design, encapsulation enforces information hiding, treating objects as black boxes to reduce dependencies and interference. Inheritance establishes hierarchies where subclasses share and extend the structure and behavior of superclasses, facilitating code reuse and specialization through an "is-a" relationship. A subclass, such as TemperatureSensor inheriting from TrendSensor, can refine inherited methods or add new ones, allowing iterative refinement of the class lattice during design. This mechanism supports the creation of extensible models by building upon established abstractions, though careful management is needed to avoid deep or tangled hierarchies. Polymorphism enables objects of different classes to respond uniquely to the same message or operation, promoting flexibility and interchangeability via a shared interface. For example, diverse sensor types might all implement a currentValue method, with behavior varying by object type through late binding or method overriding. In OOAD, this principle is particularly valuable when multiple classes adhere to common protocols, allowing uniform treatment of related objects and simplifying system evolution. Beyond these pillars, object relationships in OOAD include association, aggregation, and composition, which specify how objects interact structurally. Association denotes a semantic dependency or connection between objects, such as a Controller linking to a Blackboard, without implying ownership and allowing bidirectional navigation. Aggregation represents a whole-part relationship where parts can exist independently, like subsystems in an aircraft, marking a weaker form of containment with separate lifecycles. Composition, a stronger variant, enforces strict ownership where parts' lifetimes coincide with the whole, as in hardware components of a computer, often visualized with nesting to indicate inseparability. These relationship types enable precise modeling of dependencies during analysis, informing how objects collaborate in the system.Advantages and Challenges

Object-oriented analysis and design (OOAD) offers several key advantages in software development, primarily stemming from its emphasis on modularity and encapsulation. These principles localize design decisions, making systems more resilient to changes and easier to maintain over time. For instance, modifications to specific components, such as hardware interfaces or feature additions like payroll processing, can be isolated without widespread impacts. Reusability is another core benefit, achieved through inheritance, components, and frameworks, which allows classes and mechanisms to be shared across projects, reducing overall code volume and development effort, as demonstrated in applications like model-view-controller paradigms and reusable domain-specific classes. In larger projects, thoughtful planning of classes is particularly beneficial in OOAD. It promotes a cleaner architecture by encouraging the breakdown of complex systems into modular, single-responsibility components, reducing redundancy and improving overall structure. This approach enhances maintenance and scalability, as localized changes minimize the risk of unintended side effects and allow for easier adaptation to growing requirements. Thoughtful class planning also prevents the emergence of spaghetti code by enforcing clear interfaces and structured object interactions, avoiding tangled dependencies. Adherence to principles like SOLID—encompassing single responsibility, open-closed design, Liskov substitution, interface segregation, and dependency inversion—further supports these advantages by fostering loose coupling, code reuse, and resilience to changes. Additionally, it simplifies the addition of new features through extensible hierarchies and composition, enabling seamless integration without disrupting existing functionality.[16][17] OOAD also aligns closely with real-world problem domains by modeling entities as objects that encapsulate data and behavior, enhancing cognitive intuitiveness and expressiveness. This alignment supports scalability for large systems via hierarchical abstractions, layered architectures, and clear interfaces, enabling incremental development and handling of complexity in distributed or web-based environments. Evidence from case studies highlights these gains, including reductions in development time compared to procedural methods, attributed to early prototyping and iterative validation. Despite these strengths, OOAD presents notable challenges. The steeper learning curve compared to procedural paradigms requires developers to grasp abstract concepts like polymorphism and inheritance, particularly when shifting mindsets or acquiring domain expertise. This initial complexity can hinder adoption in teams without prior object-oriented experience. Another drawback is the risk of over-engineering, where excessive abstractions or premature decisions lead to unnecessary complexity in simpler applications, complicating designs without proportional benefits. Performance overhead arises from abstraction layers, dynamic dispatch, and polymorphism; for example, object-oriented implementations in languages like Smalltalk can be slower than procedural equivalents, though optimizations like caching may improve efficiency. Handling concurrency poses additional difficulties, as managing threads, states, and synchronization in distributed objects introduces risks like deadlocks and mutual exclusion issues, necessitating specialized patterns beyond core OOAD principles.Object-Oriented Analysis

Requirements Gathering

Requirements gathering marks the foundational phase of object-oriented analysis (OOA), where analysts elicit, document, and prioritize the system's functional and non-functional requirements by applying object-oriented principles to understand the problem domain. This process emphasizes capturing the essence of real-world entities and their interactions from the perspectives of stakeholders, ensuring the resulting model remains independent of any specific implementation technology. The goal is to establish a clear boundary for the system while identifying core abstractions that represent the problem space, often through iterative refinement based on feedback.[2] Stakeholder interviews serve as a primary technique, involving structured discussions with domain experts, end-users, and other affected parties to uncover needs, constraints, and expectations. These interviews facilitate the exploration of the problem domain by probing for tangible entities, roles, and events, helping analysts distinguish between essential requirements and peripheral details. Complementing interviews, domain analysis systematically examines the general field of business or application interest, identifying common objects, operations, and relationships perceived as important by experts in that area. This analysis draws from problem statements and existing systems to build a generic model of reusable concepts, such as entities and their associations, without assuming a particular solution architecture.[2][18] Use case development, pioneered by Ivar Jacobson in the late 1980s, provides a structured way to document requirements by defining actors—external entities interacting with the system—and scenarios outlining sequences of actions to achieve specific goals. Each use case captures a complete story of system usage, including preconditions, postconditions, and alternative flows, thereby addressing both functional requirements (e.g., specific behaviors like data processing) and non-functional requirements (e.g., performance metrics or usability standards). By focusing on observable interactions, use cases help validate requirements with stakeholders and reveal gaps in understanding the system's scope.[19] From the gathered requirements, analysts identify candidate objects, attributes, and behaviors through techniques like noun-verb analysis, where nouns in requirement descriptions suggest potential objects and attributes, while verbs indicate behaviors or operations. Functional needs translate into object responsibilities, such as processing inputs or maintaining state, whereas non-functional needs inform attributes like security levels or response times. This extraction process ensures objects encapsulate related data and actions, promoting cohesion in the emerging model.[2] Class-Responsibility-Collaboration (CRC) cards offer a collaborative brainstorming tool for exploring object roles during requirements gathering, as introduced by Ward Cunningham and Kent Beck in 1989. Each card lists a potential class, its responsibilities (what it knows or does), and collaborators (other classes it interacts with), enabling teams to simulate scenarios through role-playing to test and refine ideas. This low-fidelity technique fosters early discovery of object interactions and dependencies, particularly useful for handling complex functional scenarios without formal notation.[20] The output of requirements gathering is an initial object model that captures the problem domain's key concepts, including preliminary classes, their attributes, behaviors, and high-level relationships, serving as a conceptual foundation free from design or implementation specifics. This model provides a shared vocabulary for stakeholders and transitions into more formal modeling techniques for further refinement.[2]Modeling Techniques

In object-oriented analysis, modeling techniques are employed to construct abstract representations of the problem domain, translating raw requirements into structured, verifiable models that emphasize objects, interactions, and behaviors. These techniques facilitate the identification of key system elements and their relationships, ensuring the models align with real-world scenarios while remaining independent of implementation details. Seminal methodologies, such as those developed by Ivar Jacobson, James Rumbaugh, and Grady Booch, form the foundation for these approaches, promoting iterative refinement to achieve conceptual clarity. Use case modeling captures the functional requirements of the system by diagramming interactions between external actors—such as users or other systems—and the system itself to achieve specific goals. Introduced by Ivar Jacobson in his object-oriented software engineering approach, use cases describe scenarios of normal and exceptional flows, including preconditions, postconditions, and triggers, to specify what the system must accomplish without detailing how. The process begins with identifying actors and their goals, then elaborating each use case through textual descriptions or diagrams that outline step-by-step interactions, alternative paths, and error handling. For instance, in a library management system, a "Borrow Book" use case might involve an actor (patron) requesting a book, the system checking availability and due dates, and handling cases like overdue items, thereby validating requirements against user needs. Relationships such as <Object-Oriented Design

Architectural Design

In object-oriented design, architectural design establishes the high-level structure of the system, organizing its components and their interactions to achieve modularity, scalability, and maintainability. This involves defining the overall blueprint that arranges classes, objects, and subsystems into a coherent framework, often drawing from analysis models to translate requirements into a solution-oriented structure. Initial planning of classes is particularly beneficial for projects beyond tiny scripts, as it leads to cleaner architecture, easier maintenance and scalability, prevents spaghetti code, follows SOLID principles, and simplifies adding features.[21][22] The architecture emphasizes abstraction levels where objects collaborate through well-defined interfaces, ensuring the system can evolve without widespread disruption.[2] A common approach to defining system architecture in object-oriented design is through layered organization, which partitions the system into horizontal strata such as the presentation layer for user interfaces, the business layer for core logic and rules, and the data layer for persistence and storage. These layers interact vertically via objects that encapsulate responsibilities and communicate through controlled interfaces, with higher layers depending on lower ones to provide services like data retrieval or processing. For instance, a presentation object might invoke a business object to validate inputs before accessing data objects, promoting separation of concerns and reusability across the system. This layered model supports distributed environments, such as client-server setups, where objects in the presentation layer (e.g., user interface components) interact remotely with business and data layers.[23][2] Subsystems and packages form the building blocks of this architecture, with subsystems representing modular, interrelated clusters of objects that handle specific functionalities, such as traffic management or data processing units. Packages group logically related classes and subsystems to enforce boundaries and visibility, enabling hierarchical nesting where inner packages expose only necessary interfaces to outer ones. High-level class diagrams visualize these elements, depicting major classes, their relationships (e.g., inheritance or aggregation), and subsystem boundaries to illustrate the system's macro-structure without delving into implementation details. This identification process ensures the architecture aligns with system requirements by partitioning complexity into manageable, cohesive units.[2] Central to architectural design are principles like high cohesion and low coupling, which guide the organization of objects and subsystems. Cohesion refers to the degree to which elements within an object or subsystem focus on a single, well-defined purpose, such as grouping related behaviors in a class to maintain internal consistency and reduce complexity. Loose coupling minimizes dependencies between objects or subsystems, allowing changes in one component (e.g., updating a data access object) without affecting others, thereby enhancing reusability and adaptability. These principles are applied by designing clear boundaries and minimal interconnections, as seen in object-oriented systems where strong intracomponent links contrast with weak intercomponent associations.[24][2] Architectural patterns further refine this structure, with the Model-View-Controller (MVC) serving as a foundational example for separation of concerns in user-centric systems. In MVC, the model encapsulates data and business logic as objects, the view handles presentation through display objects, and the controller manages user inputs by coordinating interactions between model and view objects. This pattern decouples these components, enabling independent development—for instance, updating the view without altering the model—and supports scalable architectures like graphical user interfaces. Originating from early object-oriented environments, MVC promotes modularity by isolating application logic from display and control mechanisms.[25][2]Detailed Design Elements

In object-oriented design (OOD), detailed design elements involve specifying the internal structure and behavior of individual classes and their interconnections to ensure the system is implementable and maintainable. This phase refines the high-level models from analysis into precise blueprints that guide coding, emphasizing encapsulation, modularity, and adherence to object-oriented principles. Key aspects include defining class internals, refining relationships for clarity and efficiency, applying proven design patterns, and iteratively refactoring to meet non-functional requirements such as performance and scalability.[2] Class specifications form the core of detailed design by outlining the attributes, operations, visibility levels, and behavioral contracts for each class. Attributes represent the state of an object, typically including data types, initial values, and constraints to maintain integrity; for instance, aBankAccount class might specify an attribute balance as a private double with a non-negative constraint. Operations, or methods, define the behaviors, categorized as constructors, destructors, queries (read-only), and modifiers (state-changing), with signatures including parameters, return types, and exceptions. Visibility modifiers—public for external access, private for internal use, protected for inheritance—enforce encapsulation, preventing unauthorized manipulation of object state. Method contracts, rooted in Design by Contract principles, specify preconditions (requirements for method invocation), postconditions (guaranteed outcomes), and invariants (consistent object states across operations) to verify correctness and facilitate testing.[26][27]

Relationship refinements build on initial associations by specifying exact semantics to avoid ambiguity in implementation. Multiplicities in associations indicate cardinality, such as one-to-one (e.g., a Person linked to one Passport), one-to-many (e.g., a Department to multiple Employee instances), or many-to-many (e.g., Student to Course via enrollment), ensuring proper navigation and data consistency. Generalization supports inheritance hierarchies, where subclasses inherit attributes and operations from superclasses, promoting reuse; for example, a Vehicle superclass might generalize into Car and Truck subclasses, with refinements specifying overridden methods or added specializations. Dependency links denote transient relationships where one class uses another without ownership, such as a ReportGenerator depending on a DatabaseConnection for data retrieval, helping identify coupling levels and potential ripple effects during changes. These refinements are crucial for optimizing resource allocation and maintaining loose coupling in the design.[27][2]

Design patterns provide reusable solutions to common detailed design challenges, encapsulating best practices for object interactions. The Singleton pattern ensures a class has only one instance, useful for managing shared resources like a configuration manager; it achieves this through a private constructor and a static method returning the single instance, preventing multiple instantiations across the system. The Factory pattern, conversely, abstracts object creation by defining an interface for creating objects while allowing subclasses to decide the concrete type, as in a ShapeFactory producing Circle or Rectangle instances based on input, which decouples client code from specific classes and enhances flexibility in evolving designs. These patterns, part of a broader catalog, promote code reuse and reduce complexity by addressing recurring issues like instantiation control and polymorphism.[28]

Refactoring analysis models involves systematically improving the detailed design without altering external behavior, targeting non-functional requirements like performance and maintainability. This iterative process identifies code smells—such as long methods or excessive dependencies—and applies transformations like extracting classes or simplifying inheritance chains; for example, refactoring a monolithic OrderProcessor into separate Validator, Calculator, and Persister classes distributes responsibilities and improves scalability under load. Techniques emphasize small, testable changes, often guided by metrics like cyclomatic complexity, to enhance efficiency while preserving semantics, ensuring the design evolves with changing requirements.[29]