Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

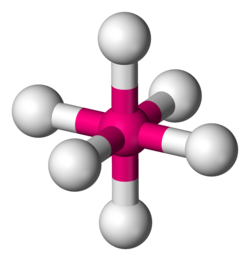

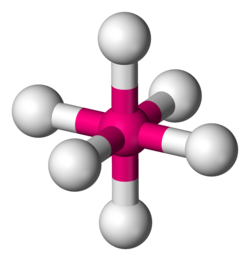

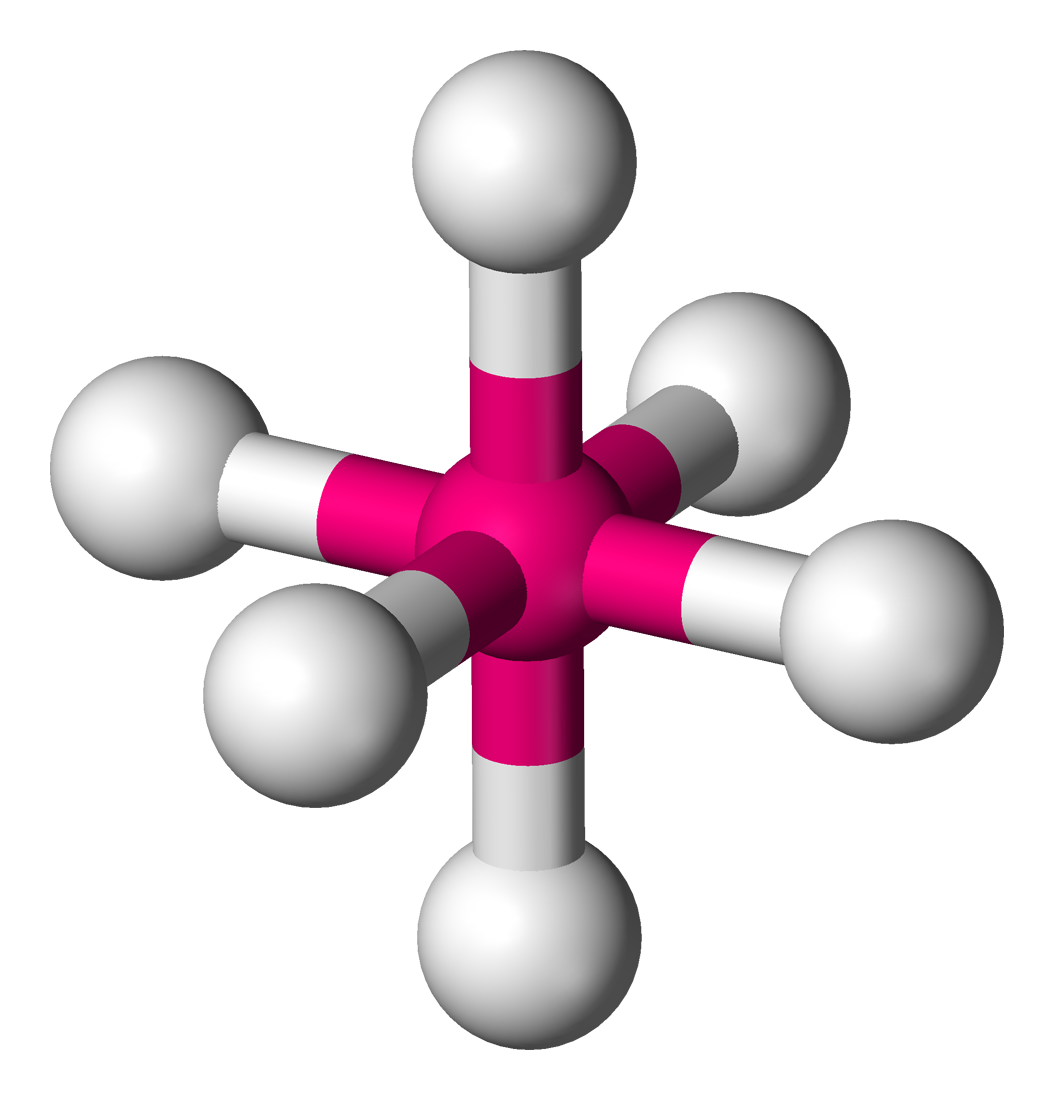

Octahedral molecular geometry

View on Wikipedia| Octahedral molecular geometry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Examples | SF6, Mo(CO)6 |

| Point group | Oh |

| Coordination number | 6 |

| Bond angle(s) | 90° |

| μ (Polarity) | 0 |

In chemistry, octahedral molecular geometry, also called square bipyramidal,[1] describes the shape of compounds with six atoms or groups of atoms or ligands symmetrically arranged around a central atom, defining the vertices of an octahedron. The octahedron has eight faces, hence the prefix octa. The octahedron is one of the Platonic solids, although octahedral molecules typically have an atom in their centre and no bonds between the ligand atoms. A perfect octahedron belongs to the point group Oh. Examples of octahedral compounds are sulfur hexafluoride SF6 and molybdenum hexacarbonyl Mo(CO)6. The term "octahedral" is used somewhat loosely by chemists, focusing on the geometry of the bonds to the central atom and not considering differences among the ligands themselves. For example, [Co(NH3)6]3+, which is not octahedral in the mathematical sense due to the orientation of the N−H bonds, is referred to as octahedral.[2]

The concept of octahedral coordination geometry was developed by Alfred Werner to explain the stoichiometries and isomerism in coordination compounds. His insight allowed chemists to rationalize the number of isomers of coordination compounds. Octahedral transition-metal complexes containing amines and simple anions are often referred to as Werner-type complexes.

Isomerism in octahedral complexes

[edit]When two or more types of ligands (La, Lb, ...) are coordinated to an octahedral metal centre (M), the complex can exist as isomers. The naming system for these isomers depends upon the number and arrangement of different ligands.

cis and trans

[edit]For MLa

4Lb

2, two isomers exist. The cis isomer has the two Lb ligands adjacent to each other, whereas the trans isomer has them 180° to each other. It was the analysis of such complexes that led Alfred Werner to the 1913 Nobel Prize–winning postulation of octahedral complexes.

-

cis-[CoCl2(NH3)4]+

-

trans-[CoCl2(NH3)4]+

Facial and meridional isomers

[edit]For MLa

3Lb

3, two isomers are possible. The facial isomer (fac) has each set of three identical ligands occupying one face of the octahedron surrounding the central atom; all of the identical ligands are cis to each other. The meridional isomer (mer) has each set of three identical ligands occupying a plane passing through the central atom; two of the three are trans to each other and the third is cis to the first two.

-

fac-[CoCl3(NH3)3]

-

mer-[CoCl3(NH3)3]

Δ vs Λ isomers

[edit]Complexes with three bidentate ligands or two cis bidentate ligands can exist as enantiomeric pairs. Examples are shown below.

-

Λ-[Fe(ox)3]3−

-

Δ-[Fe(ox)3]3−

-

Δ-cis-[CoCl2(en)2]+

Other

[edit]For MLa

2Lb

2Lc

2, a total of five geometric isomers and six stereoisomers are possible.[3]

- One isomer in which all three pairs of identical ligands are trans

- Three isomers in which one pair of identical ligands (La or Lb or Lc) is trans while the other two pairs of ligands are mutually cis.

- Two enantiomeric pair in which all three pairs of identical ligands are cis. These are equivalent to the Δ vs Λ isomers mentioned above.

The number of possible isomers can reach 30 for an octahedral complex with six different ligands (in contrast, only two stereoisomers are possible for a tetrahedral complex with four different ligands). The following table lists all possible combinations for monodentate ligands:

| Formula | Number of isomers | Number of enantiomeric pairs |

|---|---|---|

| ML6 | 1 | 0 |

| MLa 5Lb |

1 | 0 |

| MLa 4Lb 2 |

2 | 0 |

| MLa 4LbLc |

2 | 0 |

| MLa 3Lb 3 |

2 | 0 |

| MLa 3Lb 2Lc |

3 | 0 |

| MLa 3LbLcLd |

5 | 1 |

| MLa 2Lb 2Lc 2 |

6 | 1 |

| MLa 2Lb 2LcLd |

8 | 2 |

| MLa 2LbLcLdLe |

15 | 6 |

| MLaLbLcLdLeLf | 30 | 15 |

Thus, all 15 diastereomers of MLaLbLcLdLeLf are chiral, whereas for MLa

2LbLcLdLe, six diastereomers are chiral and three are not (the ones where La are trans). One can see that octahedral coordination allows much greater complexity than the tetrahedron that dominates organic chemistry. The tetrahedron MLaLbLcLd exists as a single enantiomeric pair. To generate two diastereomers in an organic compound, at least two carbon centers are required.

Deviations from ideal symmetry

[edit]Jahn–Teller effect

[edit]The term can also refer to octahedral influenced by the Jahn–Teller effect, which is a common phenomenon encountered in coordination chemistry. This reduces the symmetry of the molecule from Oh to D4h and is known as a tetragonal distortion.

Distorted octahedral geometry

[edit]Some molecules, such as XeF6 or IF−

6, have a lone pair that distorts the symmetry of the molecule from Oh to C3v.[4][5] The specific geometry is known as a monocapped octahedron, since it is derived from the octahedron by placing the lone pair over the centre of one triangular face of the octahedron as a "cap" (and shifting the positions of the other six atoms to accommodate it).[6] These both represent a divergence from the geometry predicted by VSEPR, which for AX6E1 predicts a pentagonal pyramidal shape.

Bioctahedral structures

[edit]Pairs of octahedra can be fused in a way that preserves the octahedral coordination geometry by replacing terminal ligands with bridging ligands. Two motifs for fusing octahedra are common: edge-sharing and face-sharing. Edge- and face-shared bioctahedra have the formulas [M2L8(μ-L)]2 and M2L6(μ-L)3, respectively. Polymeric versions of the same linking pattern give the stoichiometries [ML2(μ-L)2]∞ and [M(μ-L)3]∞, respectively.

The sharing of an edge or a face of an octahedron gives a structure called bioctahedral. Many metal pentahalide and pentaalkoxide compounds exist in solution and the solid with bioctahedral structures. One example is niobium pentachloride. Metal tetrahalides often exist as polymers with edge-sharing octahedra. Zirconium tetrachloride is an example.[7] Compounds with face-sharing octahedral chains include MoBr3, RuBr3, and TlBr3.

-

Ball-and-stick model of niobium pentachloride, a bioctahedral coordination compound.

-

Ball-and-stick model of zirconium tetrachloride, an inorganic polymer based on edge-sharing octahedra.

-

Ball-and-stick model of molybdenum(III) bromide, an inorganic polymer based on face-sharing octahedra.

-

View almost down the chain of titanium(III) iodide highlighting the eclipsing of the halide ligands in such face-sharing octahedra.

Trigonal prismatic geometry

[edit]For compounds with the formula MX6, the chief alternative to octahedral geometry is a trigonal prismatic geometry, which has symmetry D3h. In this geometry, the six ligands are also equivalent. There are also distorted trigonal prisms, with C3v symmetry; a prominent example is W(CH3)6. The interconversion of Δ- and Λ-complexes, which is usually slow, is proposed to proceed via a trigonal prismatic intermediate, a process called the "Bailar twist". An alternative pathway for the racemization of these same complexes is the Ray–Dutt twist.

Splitting of d-orbital energies

[edit]For a free ion, e.g. gaseous Ni2+ or Mo0, the energy of the d-orbitals are equal in energy; that is, they are "degenerate". In an octahedral complex, this degeneracy is lifted. The energy of the dz2 and dx2−y2, the so-called eg set, which are aimed directly at the ligands are destabilized. On the other hand, the energy of the dxz, dxy, and dyz orbitals, the so-called t2g set, are stabilized. The labels t2g and eg refer to irreducible representations, which describe the symmetry properties of these orbitals. The energy gap separating these two sets is the basis of crystal field theory and the more comprehensive ligand field theory. The loss of degeneracy upon the formation of an octahedral complex from a free ion is called crystal field splitting or ligand field splitting. The energy gap is labeled Δo, which varies according to the number and nature of the ligands. If the symmetry of the complex is lower than octahedral, the eg and t2g levels can split further. For example, the t2g and eg sets split further in trans-MLa

4Lb

2.

Ligand strength has the following order for these electron donors:

So called "weak field ligands" give rise to small Δo and absorb light at longer wavelengths.

Reactions

[edit]Given that a virtually uncountable variety of octahedral complexes exist, it is not surprising that a wide variety of reactions have been described. These reactions can be classified as follows:

- Ligand substitution reactions (via a variety of mechanisms)

- Ligand addition reactions, including among many, protonation

- Redox reactions (where electrons are gained or lost)

- Rearrangements where the relative stereochemistry of the ligand changes within the coordination sphere.

Many reactions of octahedral transition metal complexes occur in water. When an anionic ligand replaces a coordinated water molecule the reaction is called an anation. The reverse reaction, water replacing an anionic ligand, is called aquation. For example, the [CoCl(NH3)5]2+ slowly yields [Co(NH3)5(H2O)]3+ in water, especially in the presence of acid or base. Addition of concentrated HCl converts the aquo complex back to the chloride, via an anation process.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Trigonal bipyramidal molecular shape @ Chemistry Dictionary & Glossary". glossary.periodni.com. Retrieved 2022-07-03.

- ^ Von Zelewsky, A. (1995). Stereochemistry of Coordination Compounds. Chichester: John Wiley. ISBN 0-471-95599-X.

- ^ Miessler, G. L.; Tarr, D. A. (1999). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Prentice-Hall. p. 290. ISBN 0-13-841891-8.

- ^ Crawford, T. Daniel; Springer, Kristen W.; Schaefer, Henry F. (1994). "A contribution to the understanding of the structure of xenon hexafluoride". Journal of Chemical Physics. 102 (8): 3307–3311. Bibcode:1995JChPh.102.3307C. doi:10.1063/1.468642.

- ^ Mahjoub, Ali R.; Seppelt, Konrad (1991). "The Structure of IF−

6". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 30 (3): 323–324. doi:10.1002/anie.199103231. - ^ Winter, Mark (2015). "VSEPR and more than six electron pairs". University of Sheffield: Department of Chemistry. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

the structure of XeF6 is based upon a distorted octahedron, probably towards a monocapped octahedron

- ^ Wells, A.F. (1984). Structural Inorganic Chemistry. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-855370-6.

External links

[edit]Octahedral molecular geometry

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of Octahedral Geometry

Definition and Characteristics

Octahedral molecular geometry describes a coordination arrangement in which six ligands surround a central atom, positioned at the vertices of a regular octahedron, corresponding to a coordination number of 6.[5] This structure arises commonly in coordination compounds and molecules where the central atom, often a transition metal, bonds to six identical or similar ligands in a highly symmetric fashion.[6] In the ideal octahedral geometry, the bond angles between adjacent ligands are 90°, while the angles between ligands in opposite positions are 180°.[5] These angles reflect the geometric constraints of the octahedron, ensuring maximal separation of the ligands to minimize repulsion in valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR) theory.[6] The resulting structure exhibits O_h point group symmetry, characterized by 48 symmetry operations including rotations, reflections, and inversions, which impart isotropic properties to the molecule.[7] Due to this high symmetry and the presence of an inversion center, ideal octahedral molecules possess a zero dipole moment, as individual bond dipoles cancel out completely.[8] The geometric positions of the ligands can be mathematically represented in a Cartesian coordinate system, with the central atom at the origin (0, 0, 0) and the ligands located along the principal axes at coordinates , , and , where denotes the metal-ligand bond distance.[9] This foundational concept in coordination chemistry was established by Alfred Werner in the early 1900s through his pioneering work on the spatial arrangements in coordination compounds, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1913.[10]Examples in Chemistry

Octahedral molecular geometry is observed in various main group compounds, particularly those with six equivalent ligands surrounding a central atom from the p-block. Sulfur hexafluoride (SF₆) exemplifies this with its central sulfur atom bonded to six fluorine atoms, forming S–F bonds of about 1.56 Å and bond angles of exactly 90° and 180°, resulting in a highly symmetric structure.[11] This compound is chemically inert due to the filled octet on sulfur and strong electronegativity difference with fluorine, making it useful as an electrical insulator despite its role as a long-lived greenhouse gas. Xenon hexafluoride (XeF₆) displays a fluxional structure with minor distortions from ideal octahedral geometry caused by a stereochemically active lone pair on xenon, yet electron diffraction studies confirm a mean Xe–F bond length of 1.89 Å and overall octahedral arrangement.[12] The iodide hexafluoride anion (IF₆⁻) adopts a distorted octahedral geometry in solid salts, with iodine at the center coordinated to six fluorines, stabilized by the negative charge distributing electron density.[13] In transition metal coordination chemistry, octahedral geometry dominates for six-coordinate complexes of d-block elements, favored by ligand field stabilization energies that lower the energy of specific d-orbital configurations relative to other geometries. For example, the hexafluorocobaltate(III) ion ([CoF₆]³⁻) features a high-spin d⁶ cobalt(III) center in an octahedral field, with Co–F bonds around 1.93 Å, exhibiting paramagnetism due to four unpaired electrons.[14] The hexaaquairon(II) cation ([Fe(H₂O)₆]²⁺) forms pale green solutions in water, with Fe–O bonds of approximately 2.12 Å in its high-spin d⁶ octahedral structure, commonly encountered in aqueous iron(II) salts. Similarly, the hexachloroplatinate(IV) anion ([PtCl₆]²⁻) shows a low-spin d⁶ platinum(IV) center with Pt–Cl bonds near 2.33 Å, known for its stability and use in analytical chemistry.[15] The hexaamminechromium(III) cation ([Cr(NH₃)₆]³⁺) is a yellow, kinetically inert complex with Cr–N bonds of about 2.07 Å, illustrating octahedral coordination with neutral ammonia ligands.| Central Atom | Ligands | Charge | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| S | 6 F | 0 | Highly stable, nonpolar, used as dielectric gas; potent greenhouse gas with atmospheric lifetime >1000 years |

| Xe | 6 F | 0 | Fluxional with lone pair distortion; reactive fluorinating agent |

| I | 6 F | -1 | Stable in ionic salts; exhibits distorted octahedral symmetry |

| Co | 6 F | -3 | High-spin paramagnetic; weak-field ligand example |

| Fe | 6 H₂O | +2 | High-spin; forms green aqueous solutions, prone to oxidation |

| Pt | 6 Cl | -2 | Low-spin diamagnetic; stable, used in gravimetric analysis |

| Cr | 6 NH₃ | +3 | High-spin, kinetically inert; yellow color, classic Werner complex; paramagnetic (3 unpaired electrons) |

![cis-[CoCl2(NH3)4]+](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/be/Cis-dichlorotetraamminecobalt%28III%29.png/120px-Cis-dichlorotetraamminecobalt%28III%29.png)

![trans-[CoCl2(NH3)4]+](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/56/Trans-dichlorotetraamminecobalt%28III%29.png/120px-Trans-dichlorotetraamminecobalt%28III%29.png)

![fac-[CoCl3(NH3)3]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/69/Fac-trichlorotriamminecobalt%28III%29.png/120px-Fac-trichlorotriamminecobalt%28III%29.png)

![mer-[CoCl3(NH3)3]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/54/Mer-trichlorotriamminecobalt%28III%29.png/120px-Mer-trichlorotriamminecobalt%28III%29.png)

![Λ-[Fe(ox)3]3−](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/df/Delta-tris%28oxalato%29ferrate%28III%29-3D-balls.png/120px-Delta-tris%28oxalato%29ferrate%28III%29-3D-balls.png)

![Δ-[Fe(ox)3]3−](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6e/Lambda-tris%28oxalato%29ferrate%28III%29-3D-balls.png/120px-Lambda-tris%28oxalato%29ferrate%28III%29-3D-balls.png)

![Λ-cis-[CoCl2(en)2]+](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/12/Delta-cis-dichlorobis%28ethylenediamine%29cobalt%28III%29.png/120px-Delta-cis-dichlorobis%28ethylenediamine%29cobalt%28III%29.png)

![Δ-cis-[CoCl2(en)2]+](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/81/Lambda-cis-dichlorobis%28ethylenediamine%29cobalt%28III%29.png/120px-Lambda-cis-dichlorobis%28ethylenediamine%29cobalt%28III%29.png)