Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

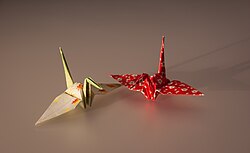

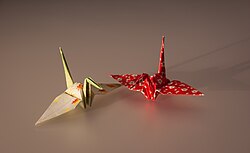

Orizuru

View on Wikipedia

The orizuru (折鶴 ori- "folded," tsuru "crane"), origami crane or paper crane, is a design that is considered to be the most classic of all Japanese origami.[1][2] In Japanese culture, it is believed that its wings carry souls up to paradise,[2] and it is a representation of the Japanese red-crowned crane, referred to as the "Honourable Lord Crane" in Japanese culture[citation needed]. It is often used as a ceremonial wrapper or restaurant table decoration.[3] A thousand orizuru strung together is called senbazuru (千羽鶴), meaning "thousand cranes", and it is said that if someone folds a thousand cranes, they are granted one wish.[4]

The significance of senbazuru is featured in Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes, a classic story based on the life of Sadako Sasaki, a hibakusha girl at Hiroshima, and then later in a book The Complete Story of Sadako Sasaki: and the Thousand Paper Cranes. Since then, senbazuru and collective effort to complete it came to be recognized as synonyms of 'wish for recovering' or 'wish for peace'. Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum exhibits two paper cranes hand-crafted and presented to the museum by President Barack Obama when he visited the city in 2016, alongside his message.

Renzuru

[edit]

The term renzuru (連鶴, "conjoined cranes") refers to an origami technique whereby one folds multiple cranes from a single sheet of paper (usually square), employing a number of strategic cuts to form a mosaic of semi-detached smaller squares from the original large square paper. The resulting cranes are attached to one another (e.g., at the tips of the beaks, wings, or tails) or at the tip of the body (e.g., a baby crane sitting on its mother's back). The trick is to fold all the cranes without breaking the small paper bridges that attach them to one another or, in some cases, to effectively conceal extra paper.

Typical renzuru configurations include a circle of four or more cranes attached at the wing tips. One of the simplest forms, made from a half-square (2×1 rectangle) cut halfway through from one of the long sides, results in two cranes that share an entire wing, positioned vertically between their bodies; heads and tails may face in the same or opposite directions. This is known as imoseyama.[5] If made from paper colored differently on each side, the cranes will be different colors.

This origami technique was first illustrated in one of the oldest known origami books, the Hiden Senbazuru Orikata (1797). (Updated diagrams from this early work can be found in a current book by Japanese origami author Kunihiko Kasahara.)

Folding the orizuru

[edit]

References

[edit]- ^ The East 1970 Page 293 "Follow the instructions on the next page. Crease the paper tightly, and you will obtain clear-cut J forms. The first in our series is the orizuru (folded crane), which is the most classic of all Japanese origami, dating back to the 6th century. The process of folding is not so simple."

- ^ a b Jccc Origami Crane Project – Materials For Teachers & Students. MEANING OF THE ORIGAMI CRANE (n.d.): n. pag. Web. 16 Feb. 2017.

- ^ Patsy Wang-Iverson, Robert J. Lang, Mark Yim Origami 5: Fifth International Meeting of Origami Science 2011 Page 8 "The older pieces are ceremonial wrappers, including ocho and mecho, and the newer ones are the traditional models we know well, such as the orizuru (crane) and yakko-san (servant) [Takagi 99]."

- ^ "Senbazuru." Senbazuru | TraditionsCustoms.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 16 Feb. 2017.

- ^ Joie Staff (2007). Crane Origami. Japan Publications Trading Company. ISBN 978-4-88996-224-6.

External links

[edit]Orizuru

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Definition

Linguistic Origins

The term orizuru (折鶴) is a compound noun in Japanese formed by combining ori (折り), the nominalized continuative form of the verb oru (折る, "to fold" or "to crease"), with tsuru (鶴), the native word for "crane," referring to the red-crowned crane (Grus japonensis). This etymological structure encapsulates the model's essence as a folded representation of the bird, distinguishing it from live cranes or other avian depictions in Japanese art.[7] The element tsuru predates the origami context, appearing in ancient Japanese literature such as the Man'yōshū (compiled circa 759 CE), where it symbolizes longevity and auspiciousness due to folklore attributing a lifespan of one thousand years to the bird.[8] The kanji 鶴 was borrowed from Middle Chinese hè (meaning "crane"), but the pronunciation tsuru reflects indigenous Japonic phonology, likely deriving from descriptive or onomatopoeic roots mimicking the bird's call or posture, though no definitive Proto-Japonic reconstruction exists beyond cognates in Ryukyuan languages. In linguistic usage, orizuru emerged specifically within the lexicon of origami (折り紙, "folded paper"), with early references in Edo-period (1603–1868) texts on paper-folding arts, underscoring its role as a descriptor rather than a proper noun.[9] This compound avoids Sino-Japanese readings, favoring kun'yomi (native Japanese readings) to evoke the tactile process of folding, aligning with the practical and symbolic traditions of Japanese craftsmanship.[7]Distinction from the Living Crane

The orizuru, derived from "ori" (folded) and "tsuru" (crane), refers exclusively to the traditional Japanese origami model crafted from a single square sheet of paper, typically measuring 15 cm per side, through 7-10 precise valley and mountain folds that form a stylized bird shape with a head, beak, body, tail, and flapping wings activated by manual tension on the head and tail.[1] This construct is inanimate, weighs mere grams, and lacks any capacity for self-sustained movement, growth, or metabolism, serving instead as a portable emblem of cultural symbolism rather than a functional organism.[2] In contrast, the living tsuru it represents is Grus japonensis, the red-crowned crane, a biological species endemic to East Asian wetlands, standing up to 150 cm tall with a 230 cm wingspan, characterized by a bare red facial patch, predominantly white plumage accented by black tertial feathers forming a trailing "bustle," gray-black legs, and a trumpeting call used in courtship dances.[10] These omnivorous birds forage in deep marshy habitats across southeastern Russia, northeastern China, Mongolia, and Japan for fish, amphibians, insects, and roots, exhibiting monogamous pair bonds, seasonal migration for non-Japanese populations, and a lifespan exceeding 25 years in the wild—up to 70 in captivity—while facing endangerment from wetland drainage and agricultural expansion, with global populations estimated at 2,500-3,000 mature individuals.[11][12][13] The orizuru's simplified geometry—featuring angular creases for wings and a reverse-fold beak—prioritizes foldability over anatomical fidelity, omitting the real crane's feathered texture, binocular vision, hydraulic skeletal structure for flight, or thermoregulatory behaviors, such as standing on one leg in cold marshes; thus, while evoking the tsuru's revered traits of fidelity and longevity through mimetic form, the paper version remains a human artifact devoid of the species' evolutionary adaptations, ecological niche, or vulnerability to environmental pressures.[10] This demarcation underscores the orizuru's role as a symbolic proxy, not a facsimile, in Japanese traditions where the actual bird's rarity amplifies its mythic status without conflating the two entities.[11]Historical Development

Pre-Modern Roots in Japanese Folklore

In Japanese folklore, the crane (tsuru), particularly the red-crowned crane (Grus japonensis), held profound symbolic significance as an emblem of longevity and prosperity, beliefs that underpin the later development of the orizuru as a paper effigy. Ancient legends asserted that cranes lived for one thousand years, a notion influenced by Chinese texts such as the Huainanzi (2nd century BCE) associating the bird with immortality and longevity, which permeated Japanese culture by the 8th to 12th centuries CE.[14] This attribution reinforced the crane's role as a harbinger of good fortune and fidelity, often paired with the tortoise in motifs representing endurance and marital loyalty.[14] Early literary depictions, such as those in the Manyoshu anthology (compiled mid-8th century CE), portrayed cranes amid natural landscapes, evoking themes of grace and auspiciousness without explicit mythological narratives.[14] Folklore also linked cranes to agrarian origins, with variants suggesting their role in introducing rice cultivation to Japan, echoed in foundational texts like the Kojiki (712 CE) and Nihon Shoki (720 CE), though direct avian attributions vary across oral traditions.[14] Central to pre-modern crane lore is the tale Tsuru no Ongaeshi ("The Gratitude of the Crane"), likely emerging in the 15th century and retold regionally, wherein a hunter rescues an injured crane that later manifests as a woman weaving ethereal brocade from its own feathers to repay the debt, only to depart upon discovery of its identity, underscoring taboos against voyeurism and the sanctity of gratitude.[14] Related motifs in tsuru nyōbō ("crane wife") stories, prevalent in rural narratives from regions like Niigata Prefecture, depict shape-shifting cranes marrying benevolent humans, symbolizing sacrifice, compassion, and the fragile reciprocity between humans and nature.[15] These narratives, devoid of paper-folding elements, established the crane's metaphysical attributes—elegance, selflessness, and otherworldliness—that would inform the orizuru's ritualistic use in ceremonial gifting during the feudal period (1185–1603 CE).[3]Emergence in Origami Practices

The orizuru, representing a crane through a series of valley and mountain folds from a square sheet, emerged as one of the earliest representational models in Japanese origami during the late 16th century, coinciding with the transition from purely ceremonial paper folding—used in Shinto rituals and gifts since the Heian period (794–1185)—to more recreational and illustrative forms. The oldest verifiable evidence appears on a kozuka (decorative knife handle) dated to 1591 or 1593, crafted by the artisan Masatsugu Tsutsumi and later documented in a 2017 Asahi Shimbun report, depicting the characteristic inflated form of the crane.[6] This artifact indicates the model's existence prior to systematic instructional literature, likely arising from practical adaptations of existing folding techniques amid Japan's increasing paper availability after widespread production began in the 12th century.[16] After a documented gap exceeding 100 years, the orizuru resurfaced in 1700 within the pattern book Tokiwa Hinagata by Koheiji Terada and Shotaro Morida, featuring a design pattern that confirms its continuity as a recognizable motif.[6] By the mid-18th century, the model gained visibility in ukiyo-e woodblock prints, including works by Suzuki Harunobu around 1770, where it symbolized elegance and was often shown in inflated states achieved by blowing air into the base—a technique persisting into the 19th century and distinguishing it from purely flat-folded designs.[6] These depictions reflect the orizuru's integration into popular culture, evolving from elite ceremonial use to accessible folding practiced by artisans and commoners during the Edo period (1603–1868).[6] A pivotal advancement occurred in 1797 with the publication of Senbazuru Orikata in Kyoto, the earliest known origami instruction book, which detailed methods for folding interconnected chains of orizuru—up to one thousand in senbazuru assemblies—transforming the single model into a scalable ritual object linked to folklore of granting wishes.[6] [16] This text, attributed to an anonymous author or Roko-an Gido, standardized the folding sequence and emphasized precision in pleating the wings and tail, embedding the orizuru deeply within origami's recreational repertoire while preserving its ties to symbolic gifting.[6] The model's persistence, evidenced by crease patterns in 1885's Kindergarten Shoho by Iijima Hanjuro, underscores its foundational role in subsequent pedagogical and artistic developments.[6]20th-Century Evolution and Documentation

In the early 20th century, orizuru folding integrated into Japanese elementary school curricula as a means to develop children's fine motor skills and spatial reasoning, marking a shift from informal folk practice to structured education. Diagrams illustrating the folding sequence appeared in pedagogical texts, such as Hideyoshi Okayama's 1903 "Jinjo Kouto Shogaku Shuko Seisakuzu," which provided visual guides for students.[6][17] Mid-century documentation advanced through specialized origami publications. Isao Honda included detailed orizuru instructions in his 1931 "Origami (Part 1)," one of the earliest comprehensive Japanese works on the craft. Akira Yoshizawa's 1954 publication of "Atarashii Origami Geijutsu" (New Origami Art) introduced a standardized diagrammatic notation system, enabling precise replication of traditional designs like the orizuru and distinguishing modern origami from earlier verbal or rudimentary visual methods.[6][18] Post-World War II texts further refined and globalized orizuru documentation. Florence Sakade's 1957 "Origami: Japanese Paper Folding," published by Charles E. Tuttle Co., offered step-by-step diagrams alongside explanations of the crane's cultural role in longevity rituals. Honda's 1959 "How to Make Origami" and 1965 "The World of Origami" provided additional standardized instructions, emphasizing accuracy in pleating and inflation techniques to achieve the model's characteristic form. These efforts evolved orizuru from a regionally transmitted motif into a universally documented emblem, supported by printed media that preserved variations while prioritizing fidelity to the traditional silhouette.[6][19]Symbolism and Traditions

Traditional Associations with Longevity and Fortune

In Japanese folklore, the red-crowned crane, known as tsuru, is revered for its legendary lifespan of 1,000 years, establishing it as a potent emblem of longevity.[20] This belief, rooted in ancient myths, portrays the crane as a messenger between heaven and earth, capable of granting extended life and vitality to those who honor it.[21] The orizuru, or folded paper crane, inherits these attributes through origami traditions, where crafting one is thought to invoke the bird's enduring spirit for personal health and prolonged existence.[6] Beyond longevity, the tsuru symbolizes good fortune and prosperity, often depicted in art and rituals to attract success and marital harmony.[22] Cranes mate for life, reinforcing ideals of fidelity and stability, which extend to wishes for familial well-being and abundance.[23] In origami practice, folding an orizuru serves as a ritualistic act to summon these blessings, with the paper form believed to carry the crane's auspicious energies into everyday life.[24] Traditional motifs pair the crane with pine trees or the sun, amplifying its connotations of eternal fortune and resilience against adversity.[25] These associations trace back to pre-modern Japanese cosmology, where the crane's graceful flight and rarity underscored its divine favor.[5] Empirical observations of the bird's migratory patterns and survival in harsh winters further cemented its role as a harbinger of positive outcomes, influencing customs like displaying crane imagery during celebrations for prosperity.[26] While modern interpretations have layered additional meanings, the core traditional links to longevity and fortune remain evident in cultural artifacts and persistent folklore.[3]Senbazuru Custom and Wishing Practices

The senbazuru custom entails the folding of one thousand origami cranes, a practice rooted in Japanese folklore where such an effort is believed to grant the folder a wish from the gods.[27] This tradition draws from the cultural symbolism of the crane (tsuru), associated with longevity due to the proverb tsuru wa sennen ("the crane lives for a thousand years"), linking the number of folds to the bird's mythical lifespan.[28] In wishing practices, senbazuru is commonly undertaken for personal or communal petitions, particularly for recovery from illness or injury, as the repetitive act is seen as channeling dedication toward healing.[27] The cranes are typically folded from colored paper, often in sets of ten strung together with thread, and may be arranged in vibrant displays to enhance their auspicious intent.[27] For marital wishes, senbazuru serves as a gift symbolizing happiness, fidelity, and good fortune, sometimes presented at shrines or temples to invoke blessings for the couple's enduring union.[29] These practices emphasize individual or collective effort, with the completed strands often dedicated at religious sites or kept as talismans, reflecting a folk belief in the crane's power to mediate divine favor without reliance on formalized rituals.[28] While the custom's efficacy remains a matter of cultural faith rather than empirical verification, its persistence underscores the value placed on perseverance in Japanese wishing traditions.[27]Post-War Reinterpretation as a Peace Symbol

Sadako Sasaki, a two-year-old Hiroshima resident exposed to radiation from the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945, was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in early 1955.[30] Inspired by the traditional Japanese legend that folding one thousand origami cranes would grant a wish for good health, she began folding orizuru from available materials, including medicine wrappers and gift paper, while hospitalized.[31] Despite folding hundreds—accounts vary, with some estimating over one thousand—Sasaki died on October 25, 1955, at age twelve, prompting her classmates to complete the senbazuru and associate the practice with broader anti-nuclear sentiments amid Japan's post-war pacifism.[32] Her story, disseminated through school campaigns and media, catalyzed the cranes' shift from symbols of personal longevity to emblems of collective peace and opposition to nuclear weapons.[33] In 1958, Sasaki's classmates raised funds through crane-folding drives to erect the Children's Peace Monument in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, depicting her holding a golden orizuru with the inscription: "This is our cry: This is our prayer: Peace in the world."[30] The monument, dedicated on May 5, 1958, by sculptor Kazuo Kikuchi, became a focal point for hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) remembrance and children's anti-war activism, receiving ongoing tributes of folded cranes from global donors.[31] This reinterpretation gained international traction during the Cold War, as origami cranes were adopted in peace movements protesting nuclear proliferation; for instance, strings of senbazuru were sent to Hiroshima from the United States and Europe starting in the late 1950s.[32] By the 1960s, the orizuru symbolized resilience against atomic devastation, influencing cultural artifacts like Eleanor Coerr's 1977 children's book Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes, which further embedded the motif in global education on nuclear disarmament.[30] Today, the practice persists at sites like the United Nations, where paper cranes represent wishes for conflict resolution, though rooted in Japan's post-war constitution renouncing war.[33]Folding Techniques

Required Materials and Preparation

A single square sheet of thin paper constitutes the essential material for folding an orizuru, with no additional tools required beyond one's hands and a flat surface for creasing.[1] Origami paper, or kami, typically weighs 50-90 grams per square meter to allow for sharp folds without tearing, and is often pre-colored on one side to enhance the model's visual contrast upon completion.[34] Standard dimensions for beginner practice measure 15 cm by 15 cm (approximately 6 inches square), yielding a finished crane about 10 cm tall, though sizes can vary based on the intended scale—smaller 7.5 cm squares are common for assembling senbazuru (thousand-crane strings).[35][36] Preparation begins with verifying or creating a square shape, as rectangular sheets like standard printer paper must first be converted: fold one short edge to meet the adjacent long edge, forming a right triangle, then trim the protruding rectangle to leave a perfect square.[37] Position the paper with the colored side facing down (if applicable) and the white or plain side up, as this orientation aligns with traditional instructions to expose the color externally in the final bird base form.[38] Practitioners may lightly pre-crease diagonal and midline folds to familiarize with the paper's behavior, though this is optional for experienced folders; ensuring clean, dry hands prevents slippage during manipulation.[2]Step-by-Step Folding Process

The orizuru, or traditional origami crane, requires a square sheet of paper, typically 15 cm (6 inches) on each side with one colored surface facing down at the start.[39] No tools or adhesives are needed, relying solely on precise creases and folds.[40] The process, classified as intermediate difficulty, takes 10-15 minutes for beginners and yields a bird base that forms the crane's body, wings, head, and tail.[38]- Fold the square paper in half diagonally from corner to corner, crease firmly, and unfold; repeat with the opposite diagonal to form an X crease pattern.[39]

- Fold the paper in half horizontally and vertically, creasing and unfolding each to create guiding lines.[38]

- Position the paper colored side down; bring the four corners to meet at the center, collapsing along the creases to form a smaller square (the preliminary base).[40]

- With the open end facing up, fold the top triangular flaps (right and left layers) to the center crease, creasing sharply; flip the model over and repeat on the reverse side.[39]

- Fold the top point (narrow flap) downward to align with the bottom edge, creasing well; turn over and repeat.[38]

- Grasp the upper side flaps and pull outward while pushing the top downward, flattening into a kite-shaped diamond (petal fold).[40]

- Fold the side points of the diamond inward to the center line on both layers; repeat after flipping.[39]

- Fold the bottom point upward to meet the top, creasing; then perform an inside reverse fold on the narrow ends to form the head and tail.[38]

- Gently pull the wide flaps downward to shape the wings, reverse-folding one tip for the head; blow into the body if needed to inflate and round the form.[40]

Common Variations and Advanced Forms

The kotobukizuru, or "congratulations crane," represents a traditional variation on the standard orizuru, distinguished by its elongated tail and more robust body folds that enhance stability and celebratory aesthetics, often used for events like weddings.[41] This modification, documented as a Japanese folk model, involves additional creases after the bird base to form decorative flourishes, differing from the basic orizuru primarily in post-folding adjustments rather than the core sequence.[42] Other common variations include the wavy-wing crane, which introduces undulating edges to the wings through targeted reverse folds, creating a sense of motion while retaining the traditional silhouette; this design emerged in modern tutorial contexts to add visual flair without increasing complexity significantly.[43] Simpler adaptations, such as color-reversed or bi-colored orizuru achieved via preliminary folds exposing different paper sides, allow for thematic customization but adhere closely to the canonical 18-step process.[43] Advanced forms extend beyond single-unit models, with renzuru comprising interlinked clusters of cranes folded from a single sheet, a technique originating in Kuwana City, Mie Prefecture, and first systematically documented in 1797 by Roko-an Gido in Hiden Senbazuru Orikata, which cataloged 49 types.[5] These may involve precise cuts to form multiple interconnected bodies—such as eight cranes in a circular yatsu-hashi arrangement or nine in a wave pattern—demanding advanced precision to maintain structural integrity and symmetry from one uncut or minimally incised sheet of Japanese washi paper.[5] Highly complex single-crane designs, like Robert J. Lang's flapping crane (Opus 192), incorporate over 100 folds to achieve articulated wings capable of realistic movement via string-pulling mechanisms, utilizing mathematical circle-packing algorithms for feathering and proportion accuracy, far exceeding traditional dry-folding limits.[44] Similarly, Satoshi Kamiya's flying crane employs wet-folding techniques on specialized paper to sculpt dynamic, curved wings mimicking flight aerodynamics, representing a pinnacle of contemporary origami engineering.[43] These advanced iterations prioritize anatomical fidelity and interactivity, often requiring diagrammatic software or custom tools for replication.[45]Cultural and Global Impact

Role in Japanese Arts and Rituals

The orizuru, or folded paper crane, serves as a foundational element in Japanese origami, an art form emphasizing precise geometric folding to create representational figures from a single sheet of square paper without cuts or glue. As one of the earliest and most recognized models, dating back to at least the 17th century in documented folding sequences, it exemplifies the aesthetic principles of simplicity, symmetry, and transformation inherent to origami traditions.[46] In artistic contexts, orizuru are featured in exhibitions and workshops, such as those at the Tokyo Origami Museum, where they highlight the meditative and creative aspects of the craft, often strung together in displays to evoke fluidity and multiplicity.[47] In ritual practices, orizuru hold ceremonial significance, particularly as decorations symbolizing longevity and protection. During the Tanabata festival on July 7, they form one of the seven traditional ornaments hung from bamboo branches alongside tanzaku wish papers, representing family safety and extended lifespan, with folds often numbering according to the ages of elders for personalized blessings.[48] This usage ties into broader Shinto-influenced customs where folded paper items denote purity and offerings, though orizuru specifically embody the crane's cultural attributes of fidelity and endurance.[49] Wedding ceremonies frequently incorporate senbazuru—strings of 1,000 interconnected orizuru—folded collectively by the bride, her family, or guests as a unity ritual to invoke marital harmony, prosperity, and a thousand years of happiness, drawing from folklore associating cranes with lifelong partnerships.[50] These are displayed at the venue or released symbolically, reinforcing communal participation in the rite. Beyond formal events, orizuru are folded for personal rituals, such as prayers for recovery from illness, where the act of creation is believed to channel intentions toward shrines or the afflicted, historically offered at temples for divine favor.[27]International Adoption and Adaptations

The orizuru, or origami crane, achieved widespread international recognition in the mid-20th century through the story of Sadako Sasaki, a Hiroshima survivor who folded over 1,000 cranes in 1955 while battling leukemia from the atomic bombing, symbolizing perseverance and ultimately inspiring global peace initiatives.[51] This narrative propelled its adoption beyond Japan, with the crane reinterpreted as a universal emblem of healing and anti-nuclear sentiment rather than solely traditional longevity.[52] Educational programs worldwide have integrated the orizuru into peace advocacy, notably through initiatives like the Peace Crane Project, which since the late 20th century has engaged students across continents to fold cranes inscribed with peace messages for international exchange and display, amassing millions of submissions by the 2020s to promote global harmony.[53] In the United States, Japanese diplomats have employed origami diplomacy, with Japan's Consul General in Seattle folding and distributing thousands of cranes annually since at least 2023 to bridge cultural divides and convey goodwill.[54] Diplomatic adaptations include high-profile gestures, such as U.S. President Barack Obama's folding of two orizuru during his May 2016 Hiroshima visit, presented as tokens of reflection on nuclear history and bilateral reconciliation between Japan and the United States.[55] Globally, the practice has evolved in memorial contexts, with visitors from diverse nations contributing paper cranes to Sadako's statue in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, where arrangements of thousands accumulate annually as tributes to atomic bomb victims and calls for disarmament.[56] Cultural adaptations outside Japan often emphasize contemporary themes like resilience in crises; for instance, post-2011 Tōhoku earthquake recovery efforts saw international communities fold senbazuru (strings of 1,000 cranes) for solidarity, extending the Japanese wishing custom to broader humanitarian appeals.[52] In Western settings, the crane has been incorporated into anti-war activism and public art, diverging from feudal-era gifting practices to represent collective protest, as seen in peace vigils and installations worldwide since the 1960s.[57]Therapeutic and Educational Applications

Folding orizuru serves as a therapeutic tool in occupational therapy, improving fine motor skills, visual-motor integration, and executive functions through precise manipulations of paper.[58] Programs like the Hope Crane Project at Michigan Medicine incorporate orizuru folding to provide emotional support and a sense of purpose for patients and families, emphasizing the activity's role in fostering resilience during illness.[59] In art therapy settings, constructing senbazuru—strings of 1,000 cranes—has been used in group interventions to alleviate anxiety and grief, with participants reporting enhanced mood and emotional processing after dedicated sessions.[60] These applications leverage the repetitive, focused nature of folding to promote mindfulness and tactile stimulation, aiding individuals with conditions such as dementia or post-traumatic stress.[61] Qualitative studies on origami-based art therapy, including crane folding, indicate benefits for young people with mental health challenges, such as reduced isolation and improved self-expression when combined with mindfulness techniques.[62] At institutions like Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, origami activities, including cranes, facilitate perspective shifts and emotional engagement for patients undergoing treatment.[63] However, while anecdotal and small-scale evidence supports these outcomes, larger peer-reviewed trials specifically on orizuru remain limited, with broader origami research suggesting cognitive enhancements like improved concentration and sequential reasoning.[64] In educational contexts, orizuru folding introduces students to geometric principles, such as symmetry and fractions, by demonstrating how a square sheet transforms into a three-dimensional form.[65] Initiatives like the Peace Crane Project engage schoolchildren in folding cranes to build hand-eye coordination, literacy through multilingual instructions, and global awareness via geography lessons tied to peace symbolism.[53] This hands-on activity fosters patience and problem-solving, aligning with STEM education goals by encouraging spatial visualization and logical sequencing without reliance on verbal instruction.[66] Classroom programs often integrate cultural history, teaching the Japanese origins of orizuru alongside mathematical applications, as evidenced in curricula that link paper folding to real-world engineering concepts.[67]Modern Developments and Projects

Large-Scale Installations and Records

The largest single origami crane (orizu) constructed to date measures 81.94 meters in wingspan and was assembled from a single sheet of specialty paper by 800 participants in the Peace Piece Project at Hiroshima Shudo University, Hiroshima, Japan, on August 29, 2009.[68] This installation, intended as a symbol of peace, surpassed prior efforts such as a 78.19-meter crane created in Odate, Japan, in January 2001.[69] Large-scale displays of multiple orizu often emphasize communal folding for peace advocacy, particularly linked to the Hiroshima bombings. The Guinness World Records-recognized largest such display comprised 1,956,912 paper cranes arranged in Hong Kong, China, by Fun Entertainment Limited on May 19, 2013, during a public event.[70] Similarly, 1,274,808 cranes were collectively folded and exhibited at the Shin Min Record Breaking Carnival in Suntec City, Singapore, from March 11 to 13, 2011, highlighting mass participation in origami traditions.[71] Extended chain installations, akin to amplified senbazuru (strings of 1,000 cranes), include the longest origami lei formed from orizu, measuring 15,579.7 meters and utilizing 579,658 hand-folded cranes by members of Junior Red Cross Hiroshima, Japan, on September 24, 2022, to commemorate the organization's centennial.[72] Earlier, Okinawa City achieved a Guinness-recognized chain exceeding 7,000 meters with 33,380 cranes on September 7, 2017, building on a Hiroshima precedent from 2013.[73] These projects typically involve volunteers folding standardized orizu from colored paper, strung together for public viewing to promote anti-nuclear messages.[72]Recycling and Sustainability Initiatives

Hiroshima, recipient of millions of orizuru folded as peace symbols, faces substantial paper waste from these donations, estimated at 10 tons annually.[74] To mitigate environmental impact, local initiatives recycle the cranes into reusable materials, transforming symbolic gestures into sustainable practices while preserving their cultural significance.[75] The Re:ORIZURU project, operated by EARTH Hiroshima, processes donated orizuru into recycled paper for eco-friendly products like stationery and crafts, which are distributed globally to generate employment and extend the cranes' message of peace.[76] Launched to address the accumulation at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, it emphasizes resource circulation by pulping weathered cranes and reforming them with added design elements for practical use.[76] Complementing this, the Tsuruhime program in Hiroshima converts aged orizuru into paper clay, a versatile material for molding durable items such as sculptures and accessories, thereby reducing landfill contributions from peace offerings.[77] This method, developed by a local company, specifically targets cranes sent to the city, recycling their embedded prayers into new forms without chemical additives that could compromise biodegradability.[77] Educational workshops, including the "Peace Workshop" series, incorporate origami crane recycled paper for hands-on crafting of motifs like flowers, informing participants about the pulping process—from disassembly and cleaning to sheet formation—and fostering awareness of sustainability in cultural traditions.[78] These efforts, active as of 2024, align with broader goals of waste reduction in ritual practices, though challenges persist in scaling recycling amid fluctuating donation volumes.[79]Recent Cultural Events (2020–2025)

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre organized a Virtual Senbazuru project in 2020 for Asian Heritage Month, inviting participants worldwide to fold and submit origami cranes digitally to form a collective string of one thousand, symbolizing resilience and cultural continuity amid restrictions on in-person gatherings.[80] Annual Hiroshima and Nagasaki peace commemorations incorporated orizuru folding, as seen in a 2023 event at the Japanese American Cultural & Community Center in Los Angeles, where participants aimed to fold one thousand cranes in two hours to send to Hiroshima, tying into missions promoting nuclear disarmament awareness.[81] Marking the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombings in 2025, multiple community initiatives featured orizuru. In June 2025, the Peace Crane Project in the United States called for folding one thousand cranes by September 7 to honor Hiroshima, distributing packets for participants to inscribe peace messages.[82] Physicians for Social Responsibility hosted "Cranes for Peace" workshops from August 6-9, 2025, folding one thousand cranes starting on the bombing anniversary to advocate for nuclear non-proliferation.[83] In Fresno, California, on August 18, 2025, community members placed folded cranes around peace statues during a memorial event, incorporating figures like Nelson Mandela to evoke global solidarity.[84] Cultural workshops persisted in Japan and abroad. An August 15, 2024, orizuru session in Tokushima's Naruto City, led by artist Asao Tokoro, engaged participants in creating indigo-dyed cranes as part of peace-themed gatherings.[85] Japan House London ran senbazuru workshops in July and August 2025, culminating in a display of one thousand cranes to highlight Japanese traditions.[86] At the Tanana Valley Sandhill Crane Festival on August 21, 2025, attendees folded orizuru alongside birdwatching, blending origami with Alaskan wildlife themes.[87]Criticisms and Debates

Historical Accuracy of Key Narratives

The senbazuru tradition, involving the folding of one thousand orizuru to petition for health, longevity, or good fortune, originated in Japan's Edo period (1603–1868), rooted in ancient folklore associating cranes with a lifespan of one thousand years and thus symbolic efficacy in Shinto-inspired rituals.[27] This precatory custom predates modern peace symbolism by centuries and typically entails communal offerings rather than a guaranteed individual wish, though popular retellings often simplify it as a personal entitlement to one fulfilled desire.[27] A central narrative links orizuru to Sadako Sasaki, a Hiroshima resident aged two at the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945, who succumbed to radiation-induced leukemia on October 25, 1955, at age twelve. Upon hospitalization in February 1955, inspired by the senbazuru legend conveyed by a friend, Sasaki folded cranes explicitly as a prayer for her own recovery and survival, not as a broader plea for world peace.[88][56] Historical evidence from the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum confirms she exceeded one thousand cranes, completing over 1,300 before her death, with classmates later stringing and burying them alongside her.[88][52] This contrasts with the influential Western depiction in Eleanor Coerr's 1977 historical fiction Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes, which portrays Sasaki folding only 644 cranes—her friends purportedly completing the rest posthumously—to underscore unfulfilled personal hope and perseverance against atomic aftermath.[52] Such alterations, originating from non-Japanese sources, amplified the story's dramatic appeal but diverged from primary accounts emphasizing her achievement of the senbazuru goal and sustained personal resolve.[88] Japanese records, including those from Sasaki's contemporaries and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, prioritize her individual determination to live over politicized reinterpretations as an anti-nuclear emblem, though global adaptations during the Cold War era infused the narrative with peace advocacy, sometimes at the expense of factual precision.[88] The resultant iconography transformed orizuru into a disarmament symbol, but this evolution reflects interpretive license rather than unaltered history, with the museum noting fictionalized elements in books like Coerr's shaped international perceptions more than domestic ones.[88]Environmental and Practical Concerns

The folding of orizuru, particularly in the tradition of senbazuru (one thousand cranes), involves substantial paper consumption, with each set requiring approximately 1,000 sheets of standard origami paper, typically measuring 15 cm square.[27] This usage contributes to the broader environmental costs of paper production, including deforestation for pulp sourcing—global paper industry logging accounts for about 35-40% of industrial wood harvest—and high water and energy demands, with pulp mills consuming up to 50,000 liters of water per ton of paper produced.[66] While many folders opt for recycled or scrap paper to reduce impact, commercial kits sold for senbazuru often rely on virgin materials, exacerbating landfill contributions when completed cranes are discarded after display or ritually burned, as practiced in some Japanese ceremonies.[89] Practical limitations arise from the model's complexity, classified as beginner-intermediate but demanding precise diagonal folds, valley and mountain creases, and reverse folds that challenge novices and require 10-15 minutes per crane under ideal conditions.[1] Assembling a full senbazuru thus entails 167-250 hours of focused effort, often spanning weeks or months, which deters widespread participation and highlights scalability issues for communal projects. Completed orizuru are inherently fragile, susceptible to tearing, creasing deformation from humidity or handling, and dust accumulation, necessitating careful storage in controlled environments to prevent rapid deterioration—factors that limit long-term utility beyond symbolic display.[90]Politicization and Cultural Appropriation Claims

The orizuru, or origami crane, has been politicized through its prominent role in anti-nuclear and peace advocacy, transforming a traditional symbol of longevity and good fortune into an emblem of disarmament activism. This association intensified after the 1955 death of Sadako Sasaki, a Hiroshima atomic bomb survivor, whose classmates completed a senbazuru (thousand cranes) in her memory, embedding the practice in narratives of nuclear victimhood and recovery.[91] International organizations have since instrumentalized the symbol for political ends; for example, in April 2017, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN) distributed thousands of paper cranes to delegates at a United Nations preparatory committee meeting for the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, aiming to evoke emotional support for abolition efforts.[92] Similarly, the Nuclear Threat Initiative's "Cranes for Our Future" campaign, active as of 2023, solicits global participants to fold and submit cranes—physical or virtual—as a demonstration against nuclear proliferation, framing the act as a collective policy demand.[93] These applications have sparked limited debate over the politicization of a folk art form, with some observers noting that the crane's invocation in campaigns selectively emphasizes atomic bombing aftermath while sidelining Japan's pre-1945 militarism, potentially fostering a unidirectional historical narrative.[91] In contexts like the 2013 Greenpeace France initiative, where thousands folded cranes to protest nuclear energy expansion, the symbol served as a tool for mobilizing public opinion against government policies, blending cultural ritual with environmental and security politics.[94] Proponents argue this evolution aligns with the crane's folkloric wish-granting origins, adapted to contemporary global threats, but detractors view it as co-optation that dilutes the artifact's apolitical roots in Shinto and Buddhist traditions. Claims of cultural appropriation remain marginal and largely anecdotal, surfacing in informal discussions rather than institutional critiques. Individuals outside Japan have occasionally questioned the ethics of incorporating orizuru into weddings, tattoos, or creative works, citing its Japanese provenance as a potential barrier.[95][96] However, Japanese cultural promotion—through widespread teaching of origami abroad since the mid-20th century—undermines such assertions, as the practice lacks sacred exclusivity or prohibitions against diffusion. No major Japanese authorities or peer-reviewed analyses have substantiated appropriation as a systemic issue, reflecting origami's history as an exported, adaptive craft rather than a guarded ritual.[91]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/oritsuru