Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

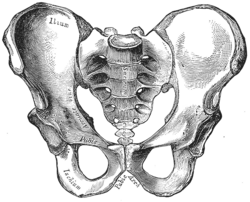

Hip bone

View on Wikipedia| Hip bone | |

|---|---|

Position of the hip bones (shown in red) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os coxae, os innominatum |

| MeSH | D010384 |

| TA98 | A02.5.01.001 |

| TA2 | 1307 |

| FMA | 16580 16585, 16580 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The hip bone (os coxae, innominate bone, pelvic bone[1][2] or coxal bone) is a large flat bone, constricted in the center and expanded above and below. In some vertebrates (including humans before puberty) it is composed of three parts: the ilium, ischium, and the pubis.

The two hip bones join at the pubic symphysis and together with the sacrum and coccyx (the pelvic part of the spine) comprise the skeletal component of the pelvis – the pelvic girdle which surrounds the pelvic cavity. They are connected to the sacrum, which is part of the axial skeleton, at the sacroiliac joint. Each hip bone is connected to the corresponding femur (thigh bone) (forming the primary connection between the bones of the lower limb and the axial skeleton) through the large ball and socket joint of the hip.[3]

Structure

[edit]

2–4. Hip bone (os coxae)

1. Sacrum (os sacrum), 2. Ilium (os ilium), 3. Ischium (os ischii)

4. Pubic bone (os pubis) (4a. corpus, 4b. ramus superior, 4c. ramus inferior, 4d. tuberculum pubicum)

5. Pubic symphysis, 6. Acetabulum (of the hip joint), 7. Obturator foramen, 8. Coccyx/tailbone (os coccygis)

Dotted. Linea terminalis of the pelvic brim.

The hip bone is formed by three parts: the ilium, ischium, and pubis. At birth, these three components are separated by hyaline cartilage. They join each other in a Y-shaped portion of cartilage in the acetabulum. By the end of puberty the three regions will have fused together, and by the age 25 they will have ossified. The two hip bones join each other at the pubic symphysis. Together with the sacrum and coccyx, the hip bones form the pelvis.[3]

Ilium

[edit]Ilium (plural ilia) is the uppermost and largest region. It makes up two fifths of the acetabulum. It is divisible into two parts: the body and the ala or wing of ilium; the separation is indicated on the top surface by a curved line, the arcuate line, and on the external surface by the margin of the acetabulum. The body of ilium forms the sacroiliac joint with the sacrum. The edge of the wing of ilium forms the S-shaped iliac crest which is easily located through the skin. The iliac crest shows clear marks of the attachment of the three abdominal wall muscles.[3]

Ischium

[edit]

The ischium forms the lower and back part of the hip bone and is located below the ilium and behind the pubis. The ischium is the strongest of the three regions that form the hip bone. It is divisible into three portions: the body, the superior ramus, and the inferior ramus. The body forms approximately one-third of the acetabulum.

The ischium forms a large swelling, the tuberosity of the ischium, also referred to colloquially as the "sit bone". When sitting, the weight is frequently placed upon the ischial tuberosity. The gluteus maximus covers it in the upright posture, but leaves it free in the seated position.[3]

Pubis

[edit]The pubic region or pubis is the ventral and anterior of the three parts forming the hip bone. It is divisible into a body, a superior ramus, and an inferior ramus. The body forms one-fifth of the acetabulum. The body forms the wide, strong, medial and flat portion of the pubic bone which unites with the other pubic bone in the pubic symphysis.[3] The fibrocartilaginous pad which lies between the symphysial surfaces of the coxal bones, that secures the pubic symphysis, is called the interpubic disc.

Pelvic brim

[edit]The pelvic brim is a continuous oval ridge of bone that runs along the pubic symphysis, pubic crests, arcuate lines, sacral alae, and sacral promontory.[4]

False pelvis, pelvic inlet, and ramus

[edit]The false pelvis is that portion superior to the pelvic brim; it is bounded by the alae of the ilia laterally and the sacral promontory and lumbar vertebrae posteriorly.[4]

The true pelvis is the region inferior to the pelvic brim that is almost entirely surrounded by bone.[4]

The pelvic inlet is the opening delineated by the pelvic brim. The widest dimension of the pelvic inlet is from left to right, that is, along the frontal plane.[4] The pelvic outlet is the margin of the true pelvis. It is bounded anteriorly by the pubic arch, laterally by the ischia, and posteriorly by the sacrum and coccyx.[4]

The superior pubic ramus is a part of the pubic bone which forms a portion of the obturator foramen. It extends from the body to the median plane where it articulates with its fellow of the opposite side. It is conveniently described in two portions: a medial flattened part and a narrow lateral prismoid portion. The inferior pubic ramus is thin and flat. It passes laterally and downward from the medial end of the superior ramus. It becomes narrower as it descends and joins with the inferior ramus of the ischium below the obturator foramen.

Development and sexual dimorphism

[edit]

The hip bone is ossified from eight centers: three primary, one each for the ilium, ischium, and pubis, and five secondary, one each for the iliac crest, the anterior inferior spine (said to occur more frequently in the male than in the female), the tuberosity of the ischium, the pubic symphysis (more frequent in the female than in the male), and one or more for the Y-shaped piece at the bottom of the acetabulum.

The centers appear in the following order: in the lower part of the ilium, immediately above the greater sciatic notch, about the eighth or ninth week of fetal life; in the superior ramus of the ischium, about the third month; in the superior ramus of the pubis, between the fourth and fifth months. At birth, the three primary centers are quite separate, the crest, the bottom of the acetabulum, the ischial tuberosity, and the inferior rami of the ischium and pubis being still cartilaginous.

By the seventh or eighth year, the inferior rami of the pubis and ischium are almost completely united by bone. About the thirteenth or fourteenth year, the three primary centers have extended their growth into the bottom of the acetabulum, and are there separated from each other by a Y-shaped portion of cartilage, which now presents traces of ossification, often by two or more centers. One of these, the os acetabuli, appears about the age of twelve, between the ilium and pubis, and fuses with them about the age of eighteen; it forms the pubic part of the acetabulum. The ilium and ischium then become joined, and lastly the pubis and ischium, through the intervention of this Y-shaped portion.

At about the age of puberty, ossification takes place in each of the remaining portions, and they join with the rest of the bone between the twentieth and twenty-fifth years. Separate centers are frequently found for the pubic tubercle and the ischial spine, and for the crest and angle of the pubis. The proportions of the female hip bone may affect the ease of passage of the baby during childbirth.

Muscle attachments

[edit]Several muscles attach to the hip bone including the internal muscles of the pelvic, abdominal muscles, back muscles, all the gluteal muscles, muscles of the lateral rotator group, hamstring muscles, two muscles from the anterior compartment of the thigh.

Abdominal muscles

[edit]- The abdominal external oblique muscle attaches to the iliac crest.

- The abdominal internal oblique muscle attaches to pecten pubis.

- The transversus abdominis muscle attaches to the pubic crest and pecten pubis via a conjoint tendon

Back muscles

[edit]- The multifidus muscle in the sacral region attaches to the medial surface of posterior superior iliac spine, the posterior sacroiliac ligaments and several places to the sacrum.

Gluteal muscles

[edit]- The gluteus maximus muscle arises from the posterior gluteal line of the inner upper ilium, and the rough portion of bone including the iliac crest, the fascia covering the gluteus medius (gluteal aponeurosis), as well as the sacrum, coccyx, the erector spinae (lumbodorsal fascia), the sacrotuberous ligament.

- The gluteus medius muscle: originates on the outer surface of the ilium between the iliac crest and the posterior gluteal line above, and the anterior gluteal line below. The gluteus medius also originates from the gluteal aponeurosis that covers its outer surface.

- Gluteus minimus muscle originates between the anterior and inferior gluteal lines, and from the margin of the greater sciatic notch.

Lateral rotator group

[edit]- The piriformis muscle originates from the superior margin of the greater sciatic notch (as well as the sacroiliac joint capsule and the sacrotuberous ligament and part of the spine and sacrum.

- The superior gemellus muscle arises from the outer surface of the ischial spine

- The obturator internus muscle arises from the inner surface of the antero-lateral wall of the hip bone, where it surrounds the greater part of the obturator foramen, being attached to the inferior rami of the pubis and ischium, and at the side to the inner surface of the hip bone below and behind the pelvic brim, reaching from the upper part of the greater sciatic foramen above and behind to the obturator foramen below and in front. It also arises from the pelvic surface of the obturator membrane except in the posterior part, from the tendinous arch, and to a slight extent from the obturator fascia, which covers the muscle.

- The inferior gemellus muscle arises from the upper part of the tuberosity of the ischium, immediately below the groove for the obturator internus tendon.

- The obturator externus muscle arises from the margin of bone immediately around the medial side of the obturator foramen, from the rami of the pubis, and the inferior ramus of the ischium; it also arises from the medial two-thirds of the outer surface of the obturator membrane, and from the tendinous arch.

Hamstrings

[edit]- The long head biceps femoris arises from the lower and inner impression on the back part of the tuberosity of the ischium, by a tendon common to it and the semitendinosus, and from the lower part of the sacrotuberous ligament;[5]

- The semitendinosus arises from the lower and medial impression on the tuberosity of the ischium, by a tendon common to it and the long head of the biceps femoris; it also arises from an aponeurosis which connects the adjacent surfaces of the two muscles to the extent of about 7.5 cm. from their origin.

- The semimembranosus arises from the lower and medial impression on the tuberosity of the ischium

Anterior compartment of thigh

[edit]- The rectus femoris muscle arises by two tendons: one, the anterior or straight, from the anterior inferior iliac spine; the other, the posterior or reflected, from a groove above the rim of the acetabulum.

- The sartorius muscle arises by tendinous fibres from the anterior superior iliac spine,

Shoulder muscles

[edit]- The latissimus dorsi muscle attaches to the iliac crest and several places on the spine and ribs.

Clinical significance

[edit]Fractures

[edit]Fractures of the hip bone are termed pelvic fractures, and should not be confused with hip fractures, which are actually femoral fractures[6] that occur in the proximal end of the femur.

Preparation for childbirth

[edit]Pelvimetry is the assessment of the female pelvis[7] in relation to the birth of a baby in order to detect an increased risk for obstructed labor.

Evolution of the pelvis in animals

[edit]The hip bone first appears in fishes, where it consists of a simple, usually triangular bone, to which the pelvic fin articulates. The hip bones on each side usually connect with each other at the forward end, and are even solidly fused in lungfishes and sharks, but they never attach to the vertebral column.[8]

In the early tetrapods, this early hip bone evolved to become the ischium and pubis, while the ilium formed as a new structure, initially somewhat rod-like in form, but soon adding a larger bony blade. The acetabulum is already present at the point where the three bones meet. In these early forms, the connection with the vertebral column is not complete, with a small pair of ribs connecting the two structures; nonetheless the pelvis already forms the complete ring found in most subsequent forms.[8]

In practice, modern amphibians and reptiles have substantially modified this ancestral structure, based on their varied forms and lifestyles. The obturator foramen is generally very small in such animals, although most reptiles do possess a large gap between the pubis and ischium, referred to as the thyroid fenestra, which presents a similar appearance to the obturator foramen in mammals. In birds, the pubic symphysis is present only in the ostrich, and the two hip bones are usually widely separated, making it easier to lay large eggs.[8]

In therapsids, the hip bone came to rotate counter-clockwise, relative to its position in reptiles, so that the ilium moved forward, and the pubis and ischium moved to the rear. The same pattern is seen in all modern mammals, and the thyroid fenestra and obturator foramen have merged to form a single space. The ilium is typically narrow and triangular in mammals, but is much larger in ungulates and humans, in which it anchors powerful gluteal muscles. Monotremes and marsupials also possess a fourth pair of bones, the prepubes or "marsupial bones", which extend forward from the pubes, and help to support the abdominal muscles and, in marsupials, the pouch. In placental mammals, the pelvis as a whole is generally wider in females than in males, to allow for the birth of the young.[8]

The pelvic bones of cetaceans were formerly considered to be vestigial, but they are now known to play a role in sexual selection.[9]

Additional images

[edit]-

Position of the hip bones (shown in red). Animation.

-

Right hip bone. Animation.

-

Right hip bone. External surface.

-

Right hip bone. Internal surface.

-

Left hip-joint, opened by removing the floor of the acetabulum from within the pelvis.

-

Hip bone.Medial view.

-

Hip bone. Lateral view.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 231 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 231 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ "hip bone". Merriam Webster. 28 May 2025.

- ^ "The hip bone is an irregularly shaped bone, also known as the pelvic girdle. It consists of three bones; ilium, ischium and pubis. These three bones are also known as the innominate bones, pelvic bones or coxal bones." https://www.kenhub.com/en/library/anatomy/the-pelvis

- ^ a b c d e Bojsen-Møller, Finn; Simonsen, Erik B.; Tranum-Jensen, Jørgen (2001). Bevægeapparatets anatomi [Anatomy of the Locomotive Apparatus] (in Danish) (12th ed.). Munksgaard Danmark. pp. 237–239. ISBN 978-87-628-0307-7.

- ^ a b c d e Multiple citations to "(J Bridges)" embedded in text.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Gray's Anatomy". 1918. Archived from the original on 22 December 2009.

- ^ "hip fracture". McGraw-Hill Concise Dictionary of Modern Medicine. 2002 – via TheFreeDictionary.

- ^ "pelvimetry" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ a b c d Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 188–192. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ^ Dines, James P., et al. "Sexual selection targets cetacean pelvic bones." Evolution 68.11 (2014): 3296-3306.

External links

[edit]- hip/hip%20bones/bones3 at the Dartmouth Medical School's Department of Anatomy

Hip bone

View on GrokipediaAnatomy

Overview

The hip bone, also known as the os coxae or innominate bone, is a large, irregularly shaped flat bone that forms the lateral portion of the pelvic girdle in humans. It connects the axial skeleton (via the sacrum) to the appendicular skeleton (via the femur), providing structural support for weight transfer from the trunk to the lower limbs during locomotion. Each hip bone is composed of three primary ossified elements—the ilium, ischium, and pubis—that fuse together during development to create a single robust unit, essential for stability and mobility.[3][4] The ilium constitutes the superior, expanded portion of the hip bone, resembling a wing-like flare that broadens the pelvic structure laterally. It features the prominent iliac crest superiorly, which serves as an attachment site for abdominal and back muscles, and the auricular surface posteriorly for articulation with the sacrum at the sacroiliac joint. Inferiorly, the ilium contributes to the acetabulum, a deep, cup-shaped socket that accommodates the head of the femur to form the hip joint. The ischium forms the posterior-inferior aspect, including the robust ischial tuberosity for weight-bearing when seated and the greater sciatic notch, which allows passage of major nerves and vessels to the lower limb. The pubis, the anterior-inferior component, consists of a body and superior/inferior rami; the bodies of the left and right pubes meet at the pubic symphysis, a cartilaginous joint, while the rami border the obturator foramen—a large opening transmitting the obturator nerve and vessels.[3][4] These three bones develop separate ossification centers in utero but remain distinct until they begin fusing at the triradiate cartilage during puberty, with complete fusion typically occurring by ages 16-18. The acetabulum, formed by contributions from all three bones, is deepened by the acetabular labrum and reinforced by ligaments such as the iliofemoral, pubofemoral, and ischiofemoral, ensuring a secure ball-and-socket articulation. The obturator foramen, bounded by the pubis and ischium, is largely covered by the obturator membrane, except for small nutrient foramina. Overall, the hip bone's architecture balances strength for load-bearing with flexibility for bipedal gait, while also protecting pelvic viscera.[3][4]Ilium

The ilium is the largest and most superior of the three bones that fuse to form the os coxae, or hip bone, in adults. It has a broad, fan-shaped structure consisting of a superior ala (wing) and an inferior body, which contributes to the formation of the acetabulum, the socket of the hip joint. The ilium's ala flares laterally and superiorly, providing a wide base for weight transmission from the trunk to the lower limbs, while its body tapers to articulate with the ischium and pubis. This configuration supports the pelvis's role in locomotion and stability.[5] Key features of the ilium include the iliac crest, a curved superior border that forms the iliac tuberosity medially and extends approximately 5 cm from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the tubercle of the crest. The ASIS is a prominent anterior projection at the end of the iliac crest, serving as an attachment for the inguinal ligament and sartorius muscle, while the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) marks the posterior end, often visible as a skin dimple overlying the S2 vertebral level. Inferiorly, the anterior inferior iliac spine (AIIS) and posterior inferior iliac spine (PIIS) provide attachments for muscles like the rectus femoris and posterior sacroiliac ligaments, respectively. The medial surface features the concave iliac fossa, which houses the iliacus muscle, and the rough auricular surface for articulation with the sacrum. Laterally, the gluteal surface displays ridges for gluteal muscle attachments, and the posterior border includes the large greater sciatic notch, which transmits major neurovascular structures like the sciatic nerve. The arcuate line, a ridge on the medial aspect, forms part of the pelvic brim and separates the false pelvis above from the true pelvis below.[6][7][3] The ilium articulates posteriorly with the sacrum at the sacroiliac joint via its auricular surface, stabilized by strong anterior and posterior sacroiliac ligaments that limit excessive motion and prevent hyperextension. Inferiorly, its body fuses with the ischium and pubis to form the acetabulum, while the pubis articulates anteriorly with the contralateral pubis at the pubic symphysis, which receives the femoral head for the ball-and-socket hip joint. These articulations enable the ilium to transfer compressive forces from the spine through the pelvis to the lower extremities during weight-bearing activities.[5][3][6] Functionally, the ilium serves as a key structural element in supporting upright posture and bipedal locomotion by bearing the weight of the upper body and distributing it to the femurs. It provides extensive attachment sites for muscles, including the iliacus and psoas major on the iliac fossa for hip flexion, gluteal muscles on the lateral surface for hip extension and abduction, and abdominal muscles like the transversus abdominis on the iliac crest for core stability. Ligaments such as the iliolumbar ligament anchor the ilium to the lumbar vertebrae, enhancing pelvic girdle integrity. The ilium also protects underlying pelvic organs and contributes to the pelvis's basin-like shape for visceral support.[3][5][7] Clinically, the ilium's landmarks are vital for diagnostics and procedures. The iliac crest aligns with the L4 vertebral level, guiding safe sites for lumbar punctures or bone marrow biopsies, while the ASIS is used to assess leg length discrepancies by measuring from it to the medial malleolus. PSIS dimples help locate the sacroiliac joint for evaluating sacroiliitis. Fractures of the iliac wing, often from high-impact trauma, can lead to significant hemorrhage (up to 2 liters of blood loss) and are classified using systems like Young-Burgess for stability assessment; stable lateral compression type I fractures involve the iliac wing and sacral ala but maintain pelvic ring integrity.[3][7][5]Ischium

The ischium is the posteroinferior portion of the hip bone, or os coxae, which fuses with the ilium superiorly and the pubis anteriorly to form the acetabulum.[3] It consists primarily of a body and a ramus, with the body contributing to the posterior aspect of the acetabulum and the ramus extending anteromedially.[5] This V-shaped bone supports the body during sitting and forms key boundaries of the pelvic outlet.[7] The body of the ischium is the thicker, upper portion that articulates with the ilium and pubis at the acetabulum, where it provides approximately the posterior two-fifths of the socket for the femoral head.[7] It features a posterior surface continuous with the gluteal surface of the ilium and an anterior surface that faces the obturator foramen.[5] Projecting from the body's inferior end is the ischial tuberosity, a robust, roughened prominence that serves as the primary weight-bearing structure when seated, often palpable with the thigh flexed.[7] Superior to the tuberosity lies the ischial spine, a sharp projection along the posterior border that marks the inferior limit of the greater sciatic notch.[3] The ramus of the ischium arises from the inferior aspect of the body and tuberosity, extending laterally to fuse with the inferior ramus of the pubis, thereby completing the border of the obturator foramen.[5] Its surfaces include a lateral aspect facing the thigh and a medial aspect directed toward the pelvis and perineum, contributing to the boundaries of the ischiorectal fossa.[7] The ramus is relatively flat and broad, with its medial border forming part of the subpubic angle in the pelvic floor.[3] Key features of the ischium include the greater and lesser sciatic notches on its posterior border. The greater sciatic notch, located between the ischial spine and the posterior inferior iliac spine, is a wide concavity that accommodates the passage of major neurovascular structures to the lower limb.[5] The lesser sciatic notch, situated inferior to the ischial spine and superior to the tuberosity, is smaller and bridges the sacrospinous ligament to form the lesser sciatic foramen.[7] Additionally, the ischial tuberosity often features a bursa that can become inflamed, though this is a structural adaptation for weight distribution rather than a primary anatomical variant.[7] In terms of articulations, the ischium integrates seamlessly with the ilium and pubis through cartilaginous fusion during development, culminating in a single os coxae by early adulthood, while its acetabular contribution articulates directly with the head of the femur.[3] The ischium also indirectly relates to the sacrum via the sacroiliac joint formed by the ilium, influencing pelvic stability.[5] These structural elements underscore the ischium's role in load transmission from the trunk to the lower limbs.[7]Pubis

The pubis, also known as the pubic bone, forms the anterior and inferior portion of the hip bone (os coxae), one of the three primary components alongside the ilium and ischium. It is an angulated structure that contributes to the stability of the pelvic girdle by articulating with the contralateral pubis at the midline pubic symphysis and fusing with the other hip bone elements at the acetabulum. The pubis plays a key role in supporting the pelvic floor and facilitating the passage of neurovascular structures through the pelvis.[3][8] The pubis consists of three main parts: the body, superior ramus, and inferior ramus. The body represents the superolateral portion of the pubis and forms approximately one-fifth of the acetabulum, the deep socket for the femoral head; its medial surface is covered with hyaline cartilage and participates in the fibrocartilaginous pubic symphysis joint, which includes an interpubic disc for slight mobility. The superior ramus extends laterally and superiorly from the body toward the acetabulum, forming part of the pelvic brim and the superior boundary of the obturator foramen; it features a prominent ridge known as the pecten pubis (or pectineal line) on its superior surface, which serves as the attachment site for the pectineal ligament and marks the linea terminalis of the pelvis. The inferior ramus projects inferolaterally from the body, fusing with the ramus of the ischium to complete the inferior border of the obturator foramen and contribute to the subpubic angle of the pelvic outlet.[3][5][8] Key surface features of the pubis include the pubic crest, a ridge along the superior border of the superior ramus that provides attachment for the rectus abdominis and pyramidalis muscles, ending laterally at the pubic tubercle—a small, forward-projecting process that anchors the medial end of the inguinal ligament. On the inferior aspect of the superior ramus lies the obturator groove, which transmits the obturator vessels and nerve after being bridged by the obturator membrane. These features collectively support muscle attachments and ligamentous reinforcements essential for pelvic integrity and lower limb movement.[5][8] In terms of articulations, the pubis connects anteriorly to its counterpart via the pubic symphysis, a secondary cartilaginous joint reinforced by the superior and arcuate pubic ligaments, allowing limited movement during activities like walking or childbirth. Posteriorly and laterally, the pubis integrates with the ilium and ischium at the acetabulum and triradiate cartilage (in youth), forming a cohesive hip bone that articulates with the femur at the hip joint. The obturator foramen, bounded by the rami of the pubis and ischium, is the largest opening in the hip bone and is mostly closed by the obturator membrane, except for the obturator canal.[3][5]Acetabulum and pelvic features

The acetabulum is a deep, cup-shaped cavity located on the lateral aspect of the hip bone (os coxae), serving as the socket for the head of the femur to form the ball-and-socket hip joint.[1] It is formed by the confluence of the three primary components of the hip bone: the ilium contributes the superior two-fifths, the ischium the posterior two-fifths, and the pubis the anterior one-fifth, with these elements fusing at the acetabulum by early adulthood around age 16-18.[7] The acetabulum opens laterally, inferiorly, and anteriorly, providing stability through its deep structure while allowing multiaxial movement.[6] Key structural features of the acetabulum include the lunate surface, a horseshoe-shaped articular area covered in hyaline cartilage that contacts the femoral head, and the central acetabular fossa, a non-articular roughened depression containing fibroelastic fat and the ligamentum teres.[7] The acetabular labrum, a ring of fibrocartilage attached to the acetabular rim, deepens the socket by approximately 22% in surface area and 33% in volume, enhancing joint congruence and load distribution.[1] Inferiorly, the acetabulum features a U-shaped acetabular notch, bridged by the transverse acetabular ligament, which allows passage of the obturator artery and contributes to the attachment of the ligamentum teres from the fovea capitis of the femur.[1] The cartilage is thickest in the anterosuperior region, supporting weight-bearing forces.[1] Beyond the acetabulum, the hip bone exhibits several pelvic features that contribute to the overall structure and function of the bony pelvis. The obturator foramen, a large oval opening in the anteroinferior hip bone, is bounded by the pubis superiorly and ischium inferiorly, serving as a passageway for vessels and nerves while reducing pelvic weight.[6] The greater sciatic notch, a wide indentation on the posterior ilium and ischium, is converted into the greater sciatic foramen by the sacrospinous ligament, allowing exit of the sciatic nerve and other structures from the pelvis.[6] Adjacent to it, the smaller lesser sciatic notch on the ischium forms the lesser sciatic foramen with the sacrotuberous ligament, accommodating the tendon of the obturator internus muscle.[6] Additional pelvic landmarks include the auricular surface on the medial ilium, an ear-shaped roughened area that articulates with the sacrum at the sacroiliac joint, providing stability through irregular interlocking and ligamentous support.[6] The arcuate line of the ilium marks the boundary between the false and true pelvis, contributing to the pelvic brim.[6] Anteriorly, the pubic symphysis forms the midline articulation between the pubic bodies of the two hip bones, connected by fibrocartilage and ligaments.[9] These features collectively define the pelvic inlet, outlet, and canal, influencing pelvic dimensions and supporting visceral organs.[6]Development and Variation

Ossification process

The ossification of the hip bone, also known as the os coxae or innominate bone, primarily occurs through endochondral ossification, beginning with three separate primary centers for the ilium, ischium, and pubis during fetal development.[1] These centers form within cartilaginous models derived from the lateral plate mesoderm and somites, enabling the initial bony framework of the pelvis.[10] Secondary ossification centers subsequently appear postnatally, primarily at apophyses and the acetabular rim, contributing to the bone's final shape and attachment sites for muscles and ligaments. The process culminates in the fusion of these components, typically completing in early adulthood, with variations influenced by sex—females generally exhibiting earlier timelines than males.[11] The primary ossification centers emerge in utero as follows: the ilium at approximately 8 weeks of gestation (or the 56th embryonic day), the ischium at 4 to 6 months of gestation (around the 105th embryonic day), and the pubis at 4 to 5 months of gestation.[12][13] Initially, these bones remain distinct, connected by hyaline cartilage, including the key triradiate cartilage at the acetabulum, which facilitates growth and eventual integration of the ilium, ischium, and pubis.[1] Fusion begins with the ischium and pubis uniting at the ischiopubic ramus between 4 and 8 years of age.[11] The ilium then fuses to this composite structure around the acetabulum at 7 to 9 years overall, though more precisely between 11 and 15 years in females and 14 and 17 years in males.[12][11] Complete closure of the triradiate cartilage, marking full unification of the hip bone, occurs between 15 and 17 years initially and fully by 20 to 25 years.[1][12] Secondary ossification centers, totaling five in the hip bone, develop at sites of muscular stress and ligamentous attachment, ossifying via endochondral mechanisms and fusing progressively.[1] These include centers for the iliac crest, anterior superior and inferior iliac spines (on the ilium), the ischial tuberosity (on the ischium), and the os acetabuli (on the pubis, contributing to the acetabular rim). Additionally, two centers appear specifically in the acetabular cartilage at puberty to deepen the socket. The timings for these centers are summarized in the table below:| Bone/Part | Secondary Center | Appearance Age | Fusion Age |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ilium (iliac crest) | Iliac crest apophysis | 13–15 years | 15–17 years |

| Ilium | Anterior superior iliac spine | 15–17 years | 19–25 years |

| Ilium | Anterior inferior iliac spine | 13–15 years | 16 years |

| Ischium | Ischial tuberosity (apophysis) | 13–16 years | 20–21 years |

| Pubis/Acetabulum | Os acetabuli | 9–12 years | Puberty (12–15 years) |

| Acetabulum | Acetabular rim centers (two) | Puberty (11–14 years) | 20–25 years |