Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Joint.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Joint

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Joint

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

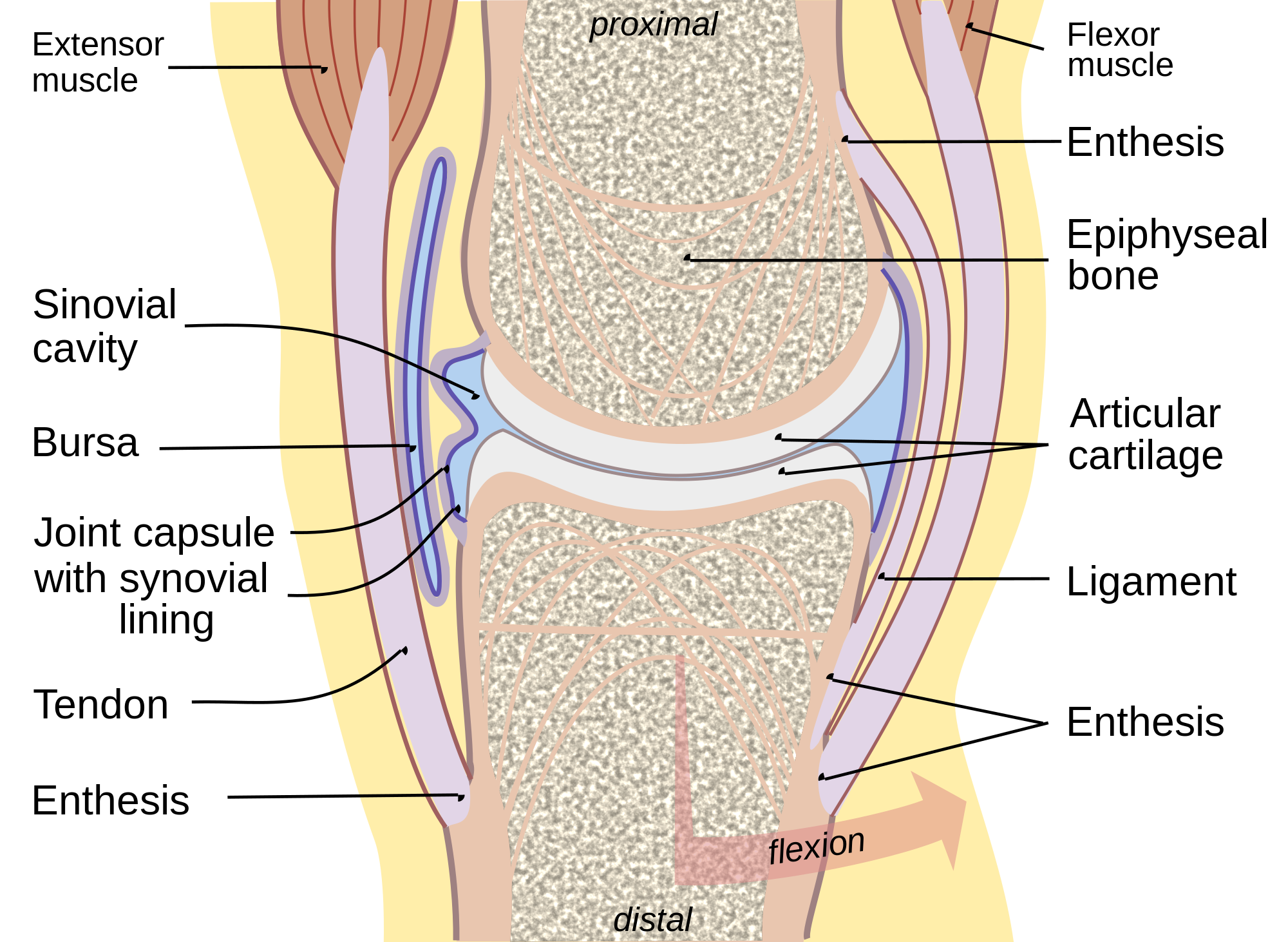

A joint, also known as an articulation, is the region where two or more bones meet and connect in the human skeleton, enabling support, stability, and movement.[1] These structures are essential for locomotion and daily activities, with most joints being mobile to allow varying degrees of motion between the connected bones.[2]

Joints are classified both histologically, based on the type of connective tissue binding the bones, and functionally, based on the degree of movement they permit.[1] Histologically, there are three main types: fibrous joints, connected by dense fibrous connective tissue with little to no movement (e.g., sutures in the skull); cartilaginous joints, linked by cartilage for limited mobility (e.g., the pubic symphysis); and synovial joints, the most common and freely movable type, characterized by a fluid-filled cavity.[3][4] Functionally, joints are categorized as synarthroses (immovable), amphiarthroses (slightly movable), or diarthroses (freely movable), with synovial joints falling into the latter group.[3][4]

Synovial joints, which include subtypes such as hinge (e.g., elbow), ball-and-socket (e.g., hip), pivot (e.g., neck), condyloid (e.g., wrist), saddle (e.g., thumb), and planar (e.g., intercarpal), feature a complex structure for optimal function.[1][5] Key components include the articular capsule (a fibrous outer layer reinforced by ligaments), the synovial membrane (which secretes lubricating synovial fluid), hyaline cartilage covering the bone ends to reduce friction, and the joint cavity containing the fluid.[1][6] This design allows for smooth, low-friction movement while providing stability against dislocation.[2]