Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

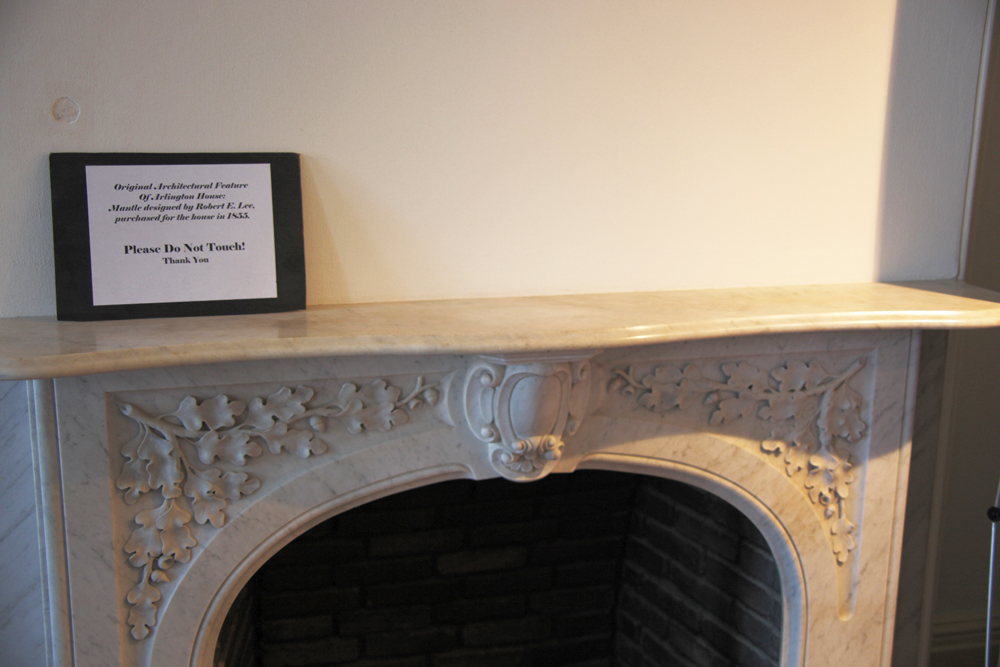

Fireplace mantel

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The fireplace mantel or mantelpiece, also known as a chimneypiece, originated in medieval times as a hood that projected over a fire grate to catch the smoke. The term has evolved to include the decorative framework around the fireplace, and can include elaborate designs extending to the ceiling. Mantelpiece is now the general term for the jambs, mantel shelf, and external accessories of a fireplace. For many centuries, the chimneypiece was the most ornamental and most artistic feature of a room, but as fireplaces have become smaller, and modern methods of heating have been introduced, its artistic as well as its practical significance has lessened.[1]

Where the fireplace continues up the wall with an elaborate construction, as in historic grand buildings, this is known as an overmantel.[2] Mirrors and paintings designed to be hung above a mantel shelf may be called "mantel mirror", "mantel painting" and so on.

History

[edit]

Up to the twelfth century, fires were simply made in the middle of a home by a hypocaust, or with braziers, or by fires on the hearth with smoke vented out through the lantern in the roof.[1] As time went on, the placement of fireplaces moved to the wall, incorporating chimneys to vent the smoke. This permitted the design of a very elaborate, rich, architectural focal point for a grand room.

At a later date, in consequence of the greater width of the fireplace, flat or segmental arches were thrown across and constructed with archivolt, sometimes joggled, with the thrust of the arch being resisted by bars of iron at the back.[1]

In domestic work of the fourteenth century, the chimneypiece was greatly increased in order to allow of the members of the family sitting on either side of the fire on the hearth, and in these cases great beams of timber were employed to carry the hood; in such cases the fireplace was so deeply recessed as to become externally an important architectural feature, as at Haddon Hall. The largest chimneypiece existing is in the great hall of the Palais des Comtes at Poitiers, which is nearly 30 feet (9.1 m) wide, having two intermediate supports to carry the hood; the stone flues are carried up between the tracery of an immense window above.[1]

The history of carved mantels is a fundamental element in the history of Western art. Every element of European sculpture can be seen on great mantels. Many of the historically noted sculptors of the past, i.e., Augustus St. Gaudens, designed and carved magnificent mantels, some of which can be found on display in the world's great museums. Exactly as the facade of a building is distinguished by its design, proportion, and detail so it is with fine mantels. The attention to carved detail is what defines a great mantel.

Today

[edit]

Up until the 20th century and the invention of mechanized contained heating systems, rooms were heated by an open or central fire. A modern fireplace usually serves as an element to enhance the grandeur of an interior space rather than as a heat source. Today, fireplaces of varying quality, materials and style are available worldwide. The fireplace mantels of today often incorporate the architecture of two or more periods or cultures.

Styles

[edit]

In the early Renaissance style, the chimneypiece of the Palais de Justice at Bruges is a magnificent example; the upper portion, carved in oak, extends the whole width of the room, with nearly life-size statues of Charles V and others of the royal family of Spain. The most prolific modern designer of chimneypieces was G. B. Piranesi, who in 1765 published a large series, on which at a later date the Empire style in France was based. In France, the finest work of the early Renaissance period is to be found in the chimneypieces, which are of infinite variety of design.[1]

The English chimneypieces of the early seventeenth century, when the purer Italian style was introduced by Inigo Jones, were extremely simple in design, sometimes consisting only of the ordinary mantel piece, with classic architraves and shelf, the upper part of the chimney breast being paneled like the rest of the room. In the latter part of the century the classic architrave was abandoned in favor of a much bolder and more effective molding, as in the chimneypieces at Hampton Court, and the shelf was omitted.[1]

In the eighteenth century, the architects returned to the Inigo Jones classic type, but influenced by the French work of Louis XIV. and XV. Figure sculpture, generally represented by graceful figures on each side, which assisted to carry the shelf, was introduced, and the over-mantel developed into an elaborate frame for the family portrait over the chimneypiece. Towards the close of the eighteenth century the designs of the Adam Brothers superseded all others, and a century later they came again into fashion. The Adam mantels are in wood enriched with ornament, cast in molds, sometimes copied from the carved wood decoration of old times.[1]

Mantels or fireplace mantels can be the focus of custom interior decoration[3]. A mantel traditionally offers a unique opportunity for the architect/designer to create a personal statement unique to the room they are creating. Historically the mantel defines the architectural style of the interior decor, whether it be traditional i.e. Classic, Renaissance, Italian, French, American, Victorian, Gothic etc.

The choice of material for the mantel includes such rich materials as marble, limestone, granite, or fine woods. Certainly the most luxurious of materials is marble. In the past only the finest of rare colored and white marbles were used. Today many of those fine materials are no longer available, however many other beautiful materials can be found worldwide. The defining element of a great mantel is the design and workmanship.

A mantel offers a unique opportunity in its design for a sculptor/artisan to demonstrate their skill in carving each of the fine decorative elements. Elements such as capitals, moldings, brackets, figurines, animals, fruits and vegetation are commonly used to decorate a mantel. One might say that a mantel can be an encyclopedia of sculpture. More than the material, it is the quality of the carving that defines the quality of the mantel piece thus highlighting the magnificence of the room.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Spiers, Richard Phené (1911). "Chimneypiece". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 165–166.

- ^ OED first citation, 1882.

- ^ Parry, Charles (3 September 2025). "Mantel Decor Ideas". Economy Home Decor. Retrieved 4 September 2025.

Further reading

[edit]- Hurdley, Rachel (2013) Home, Materiality, Memory and Belonging: Keeping Culture. London: Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 1-137-31295-5

External links

[edit]- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 384.