Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Primer (molecular biology)

View on Wikipedia

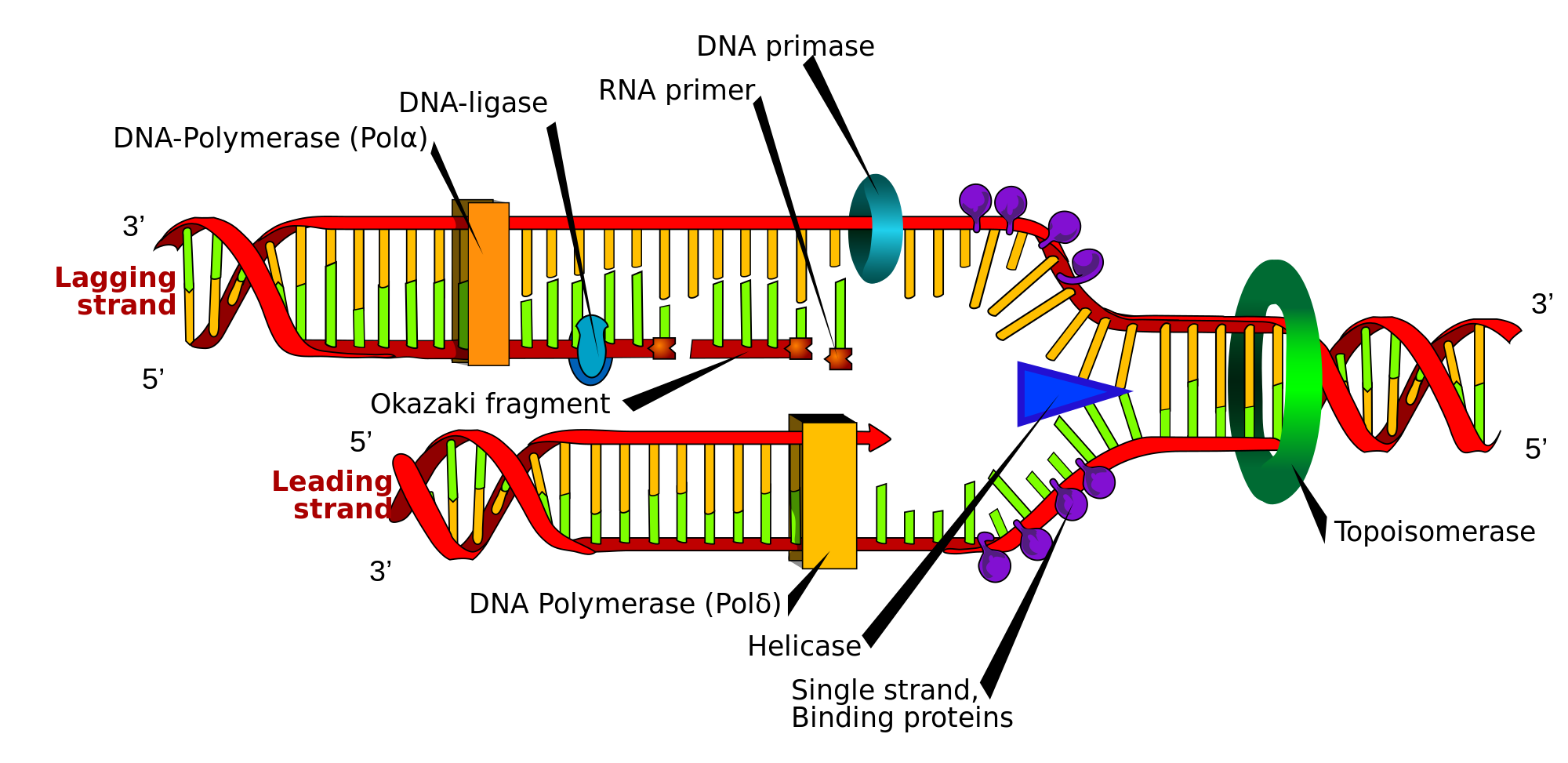

A primer is a short, single-stranded nucleic acid used by all living organisms in the initiation of DNA synthesis. A synthetic primer is a type of oligo, short for oligonucleotide. DNA polymerases (responsible for DNA replication) are only capable of adding nucleotides to the 3'-end of an existing nucleic acid, requiring a primer be bound to the template before DNA polymerase can begin a complementary strand.[1]

DNA polymerase adds nucleotides after binding to the RNA primer and synthesizes the whole strand. Later, the RNA strands must be removed accurately and replaced with DNA nucleotides. This forms a gap region known as a nick that is filled in using a ligase.[2] The removal process of the RNA primer requires several enzymes, such as Fen1, Lig1, and others that work in coordination with DNA polymerase, to ensure the removal of the RNA nucleotides and the addition of DNA nucleotides.

Living organisms use solely RNA primers, while laboratory techniques in biochemistry and molecular biology that require in vitro DNA synthesis (such as DNA sequencing and polymerase chain reaction) usually use DNA primers, since they are more temperature stable. Primers can be designed in laboratory for specific reactions such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR). When designing PCR primers, there are specific measures that must be taken into consideration, like the melting temperature of the primers and the annealing temperature of the reaction itself.

RNA primers in vivo

[edit]RNA primers are used by living organisms in the initiation of synthesizing a strand of DNA. A class of enzymes called primases add a complementary RNA primer to the reading template de novo on both the leading and lagging strands. Starting from the free 3'-OH of the primer, known as the primer terminus, a DNA polymerase can extend a newly synthesized strand. The leading strand in DNA replication is synthesized in one continuous piece moving with the replication fork, requiring only an initial RNA primer to begin synthesis. In the lagging strand, the template DNA runs in the 5′→3′ direction. Since DNA polymerase cannot add bases in the 3′→5′ direction complementary to the template strand, DNA is synthesized 'backward' in short fragments moving away from the replication fork, known as Okazaki fragments. Unlike in the leading strand, this method results in the repeated starting and stopping of DNA synthesis, requiring multiple RNA primers. Along the DNA template, primase intersperses RNA primers that DNA polymerase uses to synthesize DNA from in the 5′→3′ direction.[1]

Another example of primers being used to enable DNA synthesis is reverse transcription. Reverse transcriptase is an enzyme that uses a template strand of RNA to synthesize a complementary strand of DNA. The DNA polymerase component of reverse transcriptase requires an existing 3' end to begin synthesis.[1]

Primer removal

[edit]After the insertion of Okazaki fragments, the RNA primers are removed (the mechanism of removal differs between prokaryotes and eukaryotes) and replaced with new deoxyribonucleotides that fill the gaps where the RNA primer was present. DNA ligase then joins the fragmented strands together, completing the synthesis of the lagging strand.[1]

In prokaryotes, DNA polymerase I synthesizes the Okazaki fragment until it reaches the previous RNA primer. Then the enzyme simultaneously acts as a 5′→3′ exonuclease, removing primer ribonucleotides in front and adding deoxyribonucleotides behind. Both the activities of polymerization and excision of the RNA primer occur in the 5′→3′ direction, and polymerase I can do these activities simultaneously; this is known as "Nick Translation".[1] Nick translation refers to the synchronized activity of polymerase I in removing the RNA primer and adding deoxyribonucleotides. Later, a gap between the strands is formed called a nick, which is sealed using a DNA ligase.

In eukaryotes the removal of RNA primers in the lagging strand is essential for the completion of replication. Thus, as the lagging strand being synthesized by DNA polymerase δ in 5′→3′ direction, Okazaki fragments are formed, which are discontinuous strands of DNA. Then, when the DNA polymerase reaches to the 5' end of the RNA primer from the previous Okazaki fragment, it displaces the 5′ end of the primer into a single-stranded RNA flap which is removed by nuclease cleavage. Cleavage of the RNA flaps involves three methods of primer removal.[3] The first possibility of primer removal is by creating a short flap that is directly removed by flap structure-specific endonuclease 1 (FEN-1), which cleaves the 5' overhanging flap. This method is known as the short flap pathway of RNA primer removal.[4] The second way to cleave a RNA primer is by degrading the RNA strand using a RNase, in eukaryotes it's known as the RNase H2. This enzyme degrades most of the annealed RNA primer, except the nucleotides close to the 5' end of the primer. Thus, the remaining nucleotides are displayed into a flap that is cleaved off using FEN-1. The last possible method of removing RNA primer is known as the long flap pathway.[4] In this pathway several enzymes are recruited to elongate the RNA primer and then cleave it off. The flaps are elongated by a 5' to 3' helicase, known as Pif1. After the addition of nucleotides to the flap by Pif1, the long flap is stabilized by the replication protein A (RPA). The RPA-bound DNA inhibits the activity or recruitment of FEN1, as a result another nuclease must be recruited to cleave the flap.[3] This second nuclease is DNA2 nuclease, which has a helicase-nuclease activity, that cleaves the long flap of RNA primer, which then leaves behind a couple of nucleotides that are cleaved by FEN1. At the end, when all the RNA primers have been removed, nicks form between the Okazaki fragments that are filled-in with deoxyribonucleotides using an enzyme known as ligase1, through a process called ligation.

Uses of synthetic primers

[edit]

Synthetic primers are chemically synthesized oligonucleotides, usually of DNA, which can be customized to anneal to a specific site on the template DNA. In solution, the primer spontaneously hybridizes with the template through Watson-Crick base pairing before being extended by DNA polymerase. Both Sanger sequencing and next-generation sequencing require primers to initiate the reaction.[1]

PCR primer design

[edit]The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) uses a pair of custom primers to direct DNA elongation toward each other at opposite ends of the sequence being amplified. These primers are typically between 18 and 24 bases in length and are complementary to the specific upstream and downstream sites of the sequence being amplified.[1]

Pairs of primers are designed to have similar melting temperatures since annealing during PCR occurs for both strands simultaneously. The melting temperature is not be either too much higher or lower than the reaction's annealing temperature. If annealing temperatures are too low, non-specific structures can form, reducing the efficiency of the reaction.[5]

Additionally, primer sequences need to be chosen to uniquely select for a region of DNA, avoiding the possibility of hybridization to a similar sequence nearby. A commonly used method for selecting a primer site is BLAST search, whereby all the possible regions to which a primer may bind can be seen. Both the nucleotide sequence as well as the primer itself can be BLAST searched. The free NCBI tool Primer-BLAST integrates primer design and BLAST search into one application,[6] as do commercial software products such as ePrime and Beacon Designer. In silico PCR may be performed to evaluate the specificity of designed primers.[7]

Selecting a specific region of DNA for primer binding requires some additional considerations. Regions high in mononucleotide and dinucleotide repeats should be avoided, as loop formation can occur and contribute to mishybridization. Primers that are complementary to each other can lead to the formation of primer-dimers, lowering the efficiency of the desired reaction.[8] Primers that are able to anneal to themselves can form internal hairpins and loops that hinder hybridization with the template DNA.[8]

When designing primers, additional nucleotide bases can be added to the back ends of each primer, resulting in a customized cap sequence on each end of the amplified region. One application for this practice is for use in TA cloning, a special subcloning technique similar to PCR, where efficiency can be increased by adding AG tails to the 5′ and the 3′ ends.[9]

Degenerate primers

[edit]Some situations may call for the use of degenerate primers. These are mixtures of primers that are similar, but not identical. These may be convenient when amplifying the same gene from different organisms, as the sequences are probably similar but not identical. This technique is useful because the genetic code itself is degenerate, meaning several different codons can code for the same amino acid. This allows different organisms to have a significantly different genetic sequence that code for a highly similar protein. For this reason, degenerate primers are also used when primer design is based on protein sequence, as the specific sequence of codons are not known. Therefore, primer sequence corresponding to the amino acid isoleucine might be "ATH", where A stands for adenine, T for thymine, and H for adenine, thymine, or cytosine, according to the genetic code for each codon, using the IUPAC symbols for degenerate bases. Degenerate primers may not perfectly hybridize with a target sequence, which can greatly reduce the specificity of the PCR amplification.

Degenerate primers are widely used and extremely useful in the field of microbial ecology. They allow for the amplification of genes from thus far uncultivated microorganisms or allow the recovery of genes from organisms where genomic information is not available. Usually, degenerate primers are designed by aligning gene sequencing found in GenBank. Differences among sequences are accounted for by using IUPAC degeneracies for individual bases. PCR primers are then synthesized as a mixture of primers corresponding to all permutations of the codon sequence.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Cox, Michael M.; Doudna, Jennifer; O'Donnell, Michael, eds. (December 21, 2016). Molecular Biology: Principles and practice. W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-1-319-11637-8.

- ^ Henneke, Ghislaine (2012-09-26). "In vitro reconstitution of RNA primer removal in Archaea reveals the existence of two pathways". Biochemical Journal. 447 (2): 271–280. doi:10.1042/BJ20120959. ISSN 0264-6021. PMID 22849643.

- ^ a b Uhler, Jay P.; Falkenberg, Maria (2015-10-01). "Primer removal during mammalian mitochondrial DNA replication". DNA Repair. 34: 28–38. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.07.003. ISSN 1568-7864. PMID 26303841.

- ^ a b Balakrishnan, Lata; Bambara, Robert A. (2013-02-01). "Okazaki fragment metabolism". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 5 (2) a010173. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a010173. ISSN 1943-0264. PMC 3552508. PMID 23378587.

- ^ Bakhtiarizadeh, Mohammad Reza; Najaf-Panah, Mohammad Javad; Mousapour, Hojatollah; Salami, Seyed Alireza (March 2016). "Versatility of different melting temperature (Tm) calculator software for robust PCR and real-time PCR oligonucleotide design: A practical guide". Gene Reports. 2: 1–3. doi:10.1016/j.genrep.2015.11.001.

- ^ "Primer-BLAST". NCBI.

- ^ Kalendar, Ruslan; Shevtsov, Alexandr; Otarbay, Zhenis; Ismailova, Aisulu (7 October 2024). "In silico PCR analysis: a comprehensive bioinformatics tool for enhancing nucleic acid amplification assays". Frontiers in Bioinformatics. 4. doi:10.3389/fbinf.2024.1464197. PMC 11491563. PMID 39435190.

- ^ a b "PCR Primers". Principles and Technical Aspects of PCR Amplification. Springer Netherlands. 2008. pp. 63–90. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6241-4_5. ISBN 978-1-4020-6241-4.

- ^ Peng, Ri-He; Xiong, Ai-Sheng; Liu, Jin-ge; Xu, Fang; Bin, Cai; Zhu, Hong; Yao, Quan-Hong (April 2007). "Adenosine added on the primer 5′ end improved TA cloning efficiency of polymerase chain reaction products". Analytical Biochemistry. 363 (1): 163–165. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2007.01.014. PMID 17303063.