Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

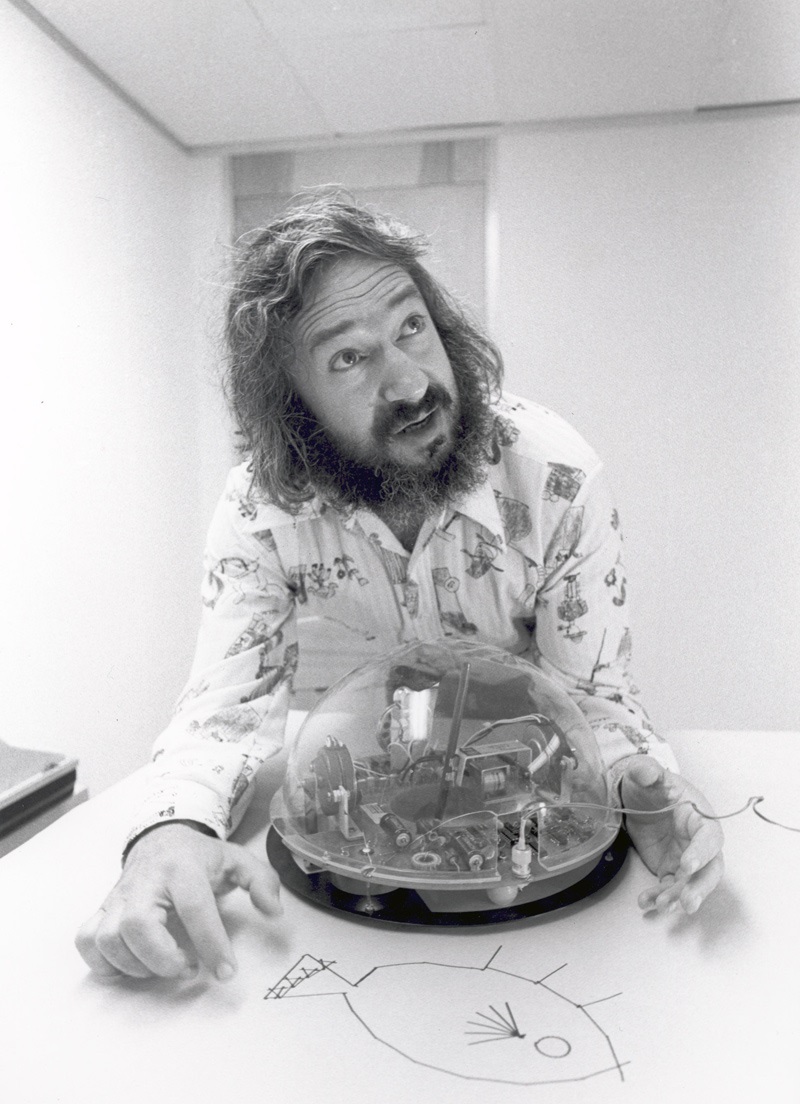

Seymour Papert

View on Wikipedia

Seymour Aubrey Papert (/ˈpæpərt/; 29 February 1928 – 31 July 2016) was a South African-born American mathematician, computer scientist, and educator, who spent most of his career teaching and researching at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[2][3][4] He was one of the pioneers of artificial intelligence, and of the constructionist movement in education.[5] He was co-inventor, with Wally Feurzeig and Cynthia Solomon, of the Logo programming language.[2][6][7][8][9]

Key Information

Early years and education

[edit]Born to a Jewish family,[10] Papert attended the University of the Witwatersrand, receiving a Bachelor of Arts degree in philosophy in 1949 followed by a PhD in mathematics in 1952.[1][11] He then went on to receive a second doctorate,[2] also in mathematics, at the University of Cambridge (1959),[12] supervised by Frank Smithies.[13]

Career

[edit]Papert worked as a researcher in a variety of places, including St. John's College, Cambridge, the Henri Poincaré Institute at the University of Paris, the University of Geneva, and the National Physical Laboratory in London before becoming a research associate at MIT in 1963.[13] He held this position until 1967, when he became professor of applied math and was made co-director of the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory by its founding director Professor Marvin Minsky, until 1981; he also served as Cecil and Ida Green professor of education at MIT from 1974 to 1981.[13]

Research

[edit]Papert worked on learning theories, and was known for focusing on the impact of new technologies on learning in general, and in schools as learning organizations in particular.

Constructionism

[edit]At MIT, Papert went on to create the Epistemology and Learning Research Group at the MIT Architecture Machine Group which later became the MIT Media Lab.[14] Here, he was the developer of a theory on learning called constructionism, built upon the work of Jean Piaget in constructivist learning theories. Papert had worked with Piaget at the University of Geneva from 1958 to 1963[15] and was one of Piaget's protégés; Piaget himself once said that "no one understands my ideas as well as Papert".[16] Papert has rethought how schools should work, based on these theories of learning.

Logo

[edit]Papert used Piaget's work in his development of the Logo programming language while at MIT. He created Logo as a tool to improve the way children think and solve problems. A small mobile robot called the "Logo Turtle" was developed, and children were shown how to use it to solve simple problems in an environment of play. A main purpose of the Logo Foundation research group is to strengthen the ability to learn knowledge.[17] Papert insisted a simple language or program that children can learn—like Logo—can also have advanced functionality for expert users.[2]

Other work

[edit]As part of his work with technology, Papert has been a proponent of the Knowledge Machine. He was one of the principals for the One Laptop Per Child initiative to manufacture and distribute The Children's Machine in developing nations.

Papert also collaborated with the construction toy manufacturer Lego on their Logo-programmable Lego Mindstorms robotics kits,[18] which were named after his groundbreaking 1980 book.[4]

A curated archive of Papert's articles, speeches, and interviews may be found on a website dedicated to Papert at: The Daily Papert.

Personal life

[edit]Papert became a political and anti-apartheid activist early in his life in South Africa. He subsequently chose self exile.[10] He was a leading figure in the revolutionary socialist circle around Socialist Review while living in London in the 1950s.[19] Papert was also a prominent activist against South African apartheid policies during his university education.[4]

Papert was married to Dona Strauss, and later to Androula Christofides Henriques.[4]

Papert's third wife was MIT professor Sherry Turkle, and together they wrote the influential paper "Epistemological Pluralism and the Revaluation of the Concrete".[20]

In his final 24 years, Papert was married to Suzanne Massie, who was a Russian scholar and author of Pavlovsk: The Life of a Russian Palace and Land of the Firebird.[4][21]

Accident in Hanoi

[edit]Papert (then aged 78), received a serious brain injury when struck by a motor scooter[4] on 5 December 2006 while crossing the street with colleague Uri Wilensky when they were both attending the 17th International Commission on Mathematical Instruction (ICMI) Study conference in Hanoi, Vietnam.[22] He underwent emergency surgery to remove a blood clot at the French Hospital of Hanoi before being transferred in a complex operation by Swiss Air Ambulance (REGA Archived 27 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine) Bombardier Challenger Jet[23] to Boston, Massachusetts, where he spent approximately four weeks in intensive care.[24][25] He was moved to a hospital closer to his home in January 2007, but then developed sepsis which damaged a heart valve, which was later replaced.

By 2008 he had returned home, could think and communicate clearly and walk "almost unaided", but still had "some complicated speech problems" and was in receipt of extensive rehabilitation support.[26] His rehabilitation team used some of the very principles of experiential, hands-on learning that he had pioneered.[27]

Papert died at his home in Blue Hill, Maine, on 31 July 2016.[4]

Awards, honours, and legacy

[edit]Papert's work has been used by other researchers in the fields of education and computer science. He influenced the work of Uri Wilensky in the design of NetLogo and collaborated with him on the study of knowledge restructurations, as well as the work of Andrea diSessa and the development of "dynaturtles". In 1981, Papert along with several others in the Logo group at MIT, started Logo Computer Systems Inc. (LCSI), of which he was board chair for over 20 years. Working with LCSI, Papert designed a number of award-winning programs, including LogoWriter[28] and Lego/Logo (marketed as Lego Mindstorms). He also influenced the research of Idit Harel Caperton, coauthoring articles and the book Constructionism, and chairing the advisory board of the company MaMaMedia. He also influenced Alan Kay and the Dynabook concept, and worked with Kay on various projects.

Papert won a Guggenheim fellowship in 1980, a Marconi International fellowship in 1981,[29] the Software Publishers Association Lifetime Achievement Award in 1994, and the Smithsonian Award from Computerworld in 1997.[30] Papert has been called by Marvin Minsky "the greatest of all living education theorists".[31]

MIT President L. Rafael Reif summarized Papert's lifetime of accomplishments: "With a mind of extraordinary range and creativity, Seymour Papert helped revolutionize at least three fields, from the study of how children make sense of the world, to the development of artificial intelligence, to the rich intersection of technology and learning. The stamp he left on MIT is profound. Today, as MIT continues to expand its reach and deepen its work in digital learning, I am particularly grateful for Seymour's groundbreaking vision, and we hope to build on his ideas to open doors to learners of all ages, around the world."[4][32][33][34]

In 2016 Papert's alma mater, University of Witwatersrand, awarded him the degree of Doctor of Science in Engineering, honoris causa.[35][36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Seymour Papert at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ^ a b c d Stager, Gary S. (2016). "Seymour Papert (1928–2016) Father of educational computing". Nature. 537 (7620). London: Springer Nature: 308. doi:10.1038/537308a. PMID 27629633.

- ^ Stager, Gary (2016). "Planet Papert: articles by and about Papert". stager.org.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Professor Emeritus Seymour Papert, pioneer of constructionist learning, dies at 88". MIT News. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 1 August 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^ Papert, Seymour (2004). "Interviews with Seymour Papert". Computers in Entertainment. 2 (1): 9. doi:10.1145/973801.973816. ISSN 1544-3574. S2CID 52800402.

- ^ "Person Overview ‹ Seymour A. Papert". MIT Media Lab. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "Professor Seymour Papert". papert.org. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "Curlie – Computers: History: Pioneers: Papert, Seymour". curlie.org. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "The Daily Papert". The Daily Papert. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ a b "Remembering Seymour Papert: Revolutionary Socialist and Father of A.I." The Forward. 3 August 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Papert, Seymour Aubrey (1952). Sequential Convergence in Lattices With Special Reference To Modular And Subgroup Lattices (PhD thesis). University of the Witwatersrand. OCLC 775688121.

- ^ Papert, Seymour Aubrey (1960). The lattices of logic and topology (PhD thesis). University of the Cambridge. ProQuest 301315242. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Papert, Seymour A. in American Men and Women of Science, R.R. Bowker. (1998–99, 20th ed). p. 1056.

- ^ "Group Overview ‹ Lifelong Kindergarten". MIT Media Lab. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "Seymour Papert". mit.edu. MIT. Archived from the original on 8 March 2015.

- ^ Thornburg, David (2013). From the campfire to the holodeck : creating engaging and powerful 21st century learning environments. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. p. 78. ISBN 9781118748060.

- ^ "Logo Foundation". el.media.mit.edu. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "LEGO Mindstorms". Archived from the original on 9 January 2006. Retrieved 19 April 2005.

- ^ "Jim Higgins: More Years for the Locust (1997)". marxists.org. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Turkle, Sherry; Papert, Seymour (1992). "Epistemological Pluralism and Revaluation of the Concrete". Journal of Mathematical Behavior. 11 (1).

- ^ "Author Suzanne Massie biography". suzannemassie.com. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "Artificial Intelligence Pioneer Seymour Papert in Coma in Hanoi". InformationWeek. 8 December 2006. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ "Seymour Papert – Informatika – 3065 – p2k.unkris.ac.id". p2k.unkris.ac.id. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "Seymour Papert". The Times. 5 September 2023. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "1969 – The Logo Turtle – Seymour Papert et al (Sth African/American)". cyberneticzoo.com. 10 January 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "Welcome to The Learning Barn ~ The Official Seymour Papert Website!". 10 March 2008. Archived from the original on 10 March 2008. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Matchan, Linda (12 July 2008). "In search of a beautiful mind". Boston Globe. Retrieved 16 July 2008.

- ^ "LogoWriter or the Elementary Curriculum". siue.edu. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "MARCONIFOUNDATION.ORG". marconifoundation.org. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ Henderson, Harry. 2003. A to Z of Computer Scientists. New York: Facts on File. p. 208.

- ^ Papert, Seymour (1993). Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas (2 ed.). MIT Press. ISBN 978-0465046744.

- ^ 25 years EIAH, colloque EIAH 2003 [1] Archived 18 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Interview from 11 July 2004, on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation network

- ^ Conférence vidéo, colloque EIAH 2003 "Canalc2 : Seymour Papert – EIAH 2003 : Environnements Informatiques pour l'Apprentissage Humain (15/04/2003)". Archived from the original on 21 December 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees - Wits University".

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 March 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Selected bibliography

[edit]- Counter-free automata (with Robert McNaughton), 1971, ISBN 0-262-13076-9

- Perceptrons (with Marvin Minsky), MIT Press, 1969 (Enlarged edition, 1988), ISBN 0-262-63111-3

- Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas, 1980, ISBN 0-465-04674-6

- Papert, S. & Harel, I. (eds). (1991) Constructionism: research reports and essays 1985–1990 by the Epistemology and Learning Research Group, the Media Lab, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ablex Pub. Corp, Norwood, NJ.

- The Children's Machine: Rethinking School in the Age of the Computer, 1993, ISBN 0-465-01063-6

- The Connected Family: Bridging the Digital Generation Gap, 1996, ISBN 1-56352-335-3

External links

[edit]- Seymour Papert Print Archives at The Daily Papert

- Seymour Papert Audio & Video Archives at The Daily Papert

- Official website

Seymour Papert

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Childhood in South Africa

Seymour Papert was born on February 29, 1928, in Pretoria, South Africa, to a Jewish family of Lithuanian descent whose experiences under the country's emerging apartheid regime exposed him to stark racial hierarchies and enforced segregation from an early age.[1][9] His father worked as an entomologist, exploring rural areas, which provided Papert with opportunities for independent exploration beyond formal schooling.[10] The apartheid system's rigid control over education and social life, including separate and unequal schooling for different racial groups, instilled in him a profound distrust of top-down institutional authority, shaping his lifelong advocacy for learner-driven alternatives to conventional pedagogy.[11][12] As a youth, Papert actively opposed apartheid by organizing informal classes for black children denied access to quality education and publicly challenging the regime's policies, experiences that highlighted the failures of coercive, state-mandated learning environments.[11] These formative encounters with systemic injustice fostered his rejection of rote, authoritarian instruction in favor of self-directed discovery, a theme that would recur in his later educational theories. His early tinkering with mechanical objects, such as gears, further reinforced this preference for concrete, manipulative engagement with mathematical concepts over abstract or imposed methods.[13] Papert pursued undergraduate studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, earning a Bachelor of Arts in philosophy in 1949 amid a politically charged atmosphere of anti-apartheid activism.[2][14] There, he engaged with Marxist ideas prevalent in leftist intellectual circles, participating in revolutionary socialist groups that critiqued capitalist and colonial structures, including South Africa's racial order.[15] However, his direct involvement in grassroots educational efforts against apartheid's constraints gradually oriented him toward individualistic, problem-solving approaches that prioritized personal agency over collective ideological frameworks.[15][11]Formative Academic Influences

Papert earned a PhD in mathematics from the University of Cambridge in 1959, with a dissertation titled "Lattices in Logic and Topology" that examined abstract algebraic structures underlying logical systems and topological spaces, providing a mathematical foundation for analyzing computational processes and automata.[16] [17] This research stressed precise, axiomatic reasoning from basic principles to uncover inherent constraints in representational systems, shaping his later insistence on causal mechanisms in cognitive and machine models over empirical trial-and-error alone.[1] Immediately following his Cambridge studies, Papert joined the International Center for Genetic Epistemology at the University of Geneva from 1958 to 1963 as a researcher under Jean Piaget, immersing himself in studies of child development and knowledge acquisition.[18] [17] Piaget's constructivist theory, which views learning as an active process of assimilating and accommodating experiences to build internal schemas, profoundly influenced Papert, yet he critiqued its abstraction by advocating integration of tangible, manipulable objects to externalize and test mental constructions.[1] These experiences converged in Papert's early explorations of pattern recognition and network models, as seen in his subsequent collaborations analyzing perceptron limitations, where he applied topological and logical tools to reveal fundamental barriers to simple machines' ability to discern complex patterns without multilayered architectures.[19] This work underscored causal dependencies in learning systems, prioritizing structural invariants over associative approximations and informing his computational theories of mind.[2]Professional Career

Initial Research in Mathematics and AI

Papert's foundational work in mathematics centered on geometry, symmetry, and cybernetic systems. After completing his undergraduate studies in South Africa, he pursued advanced research in tessellations and pattern formation, applying group theory to understand complex structures in physical and abstract systems. This early focus on mathematical modeling of emergent patterns informed his later interdisciplinary approaches, bridging pure mathematics with computational simulation.[2] From 1959 to 1963, Papert collaborated with Jean Piaget at the University of Geneva, integrating mathematical rigor with empirical observations of child cognition. He explored how children intuitively grasp geometric concepts through physical manipulation, contrasting this with the abstractions imposed by formal education. This period marked his initial foray into cybernetics, viewing learning as a feedback-driven process akin to mechanical systems, which laid groundwork for computational models of intelligence.[2] Transitioning to the United States, Papert joined MIT in the mid-1960s, where he collaborated closely with Marvin Minsky on artificial intelligence research. Their joint efforts culminated in the 1969 book Perceptrons, which provided rigorous mathematical proofs demonstrating the limitations of single-layer neural networks, such as their inability to compute non-linearly separable functions like the XOR problem without additional layers. This analysis, grounded in computational geometry and linear algebra, highlighted fundamental barriers in parallel distributed processing, influencing early critiques of connectionist AI paradigms.[20] During this phase, Papert initiated work on interactive geometric tools, including prototypes for turtle graphics around 1968–1969. These mechanical devices, controlled via early computer interfaces, enabled real-time visualization of mathematical transformations, such as rotations and translations, fostering empirical exploration of space and motion. Observations of children's superior intuitive geometry compared to rigid scholastic methods prompted Papert to pivot toward AI applications that augment human problem-solving rather than replicate adult cognition in machines.[21][11]Tenure at MIT and Development of Key Projects

Papert joined MIT's Artificial Intelligence Laboratory in 1967 as a professor of applied mathematics, where he collaborated closely with Marvin Minsky on early artificial intelligence research.[22] There, he directed the Logo Group, a team focused on creating child-accessible computing tools, leading to the refinement of the Logo programming language with integrated turtle graphics—a movable robotic device that executed commands to draw shapes on the floor or screen, enabling intuitive geometric exploration.[23] Development of turtle-based Logo accelerated in the early 1970s, with prototypes tested on systems like the DEC PDP-11, emphasizing hands-on programming over rote instruction.[24] The Logo Group's efforts extended to practical implementations, with pilots deployed in urban educational settings during the 1970s, including Boston-area programs akin to Project Head Start, where children as young as preschool age engaged with Logo to foster problem-solving through iterative debugging and pattern creation.[7] These initiatives demonstrated Logo's potential for bridging abstract mathematics and concrete action, as children programmed the turtle to navigate mazes or replicate designs, often requiring hundreds of command trials to achieve results.[25] In 1980, Papert published Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas, a seminal work detailing how programmable devices like the Logo turtle could serve as "objects-to-think-with," circumventing the math phobia engendered by conventional classroom drills by allowing learners to externalize and manipulate ideas in a low-stakes digital environment.[26] The book drew from MIT lab observations, arguing that such tools amplified children's innate debugging skills, akin to those used by professional programmers, to build mathematical intuition organically.[27] Papert's institutional influence culminated in 1985 with his role as a founding professor in the newly established MIT Media Lab, co-directed initially with Minsky, which expanded interdisciplinary experiments in learning technologies beyond pure AI into media and epistemology.[28] This lab became a hub for prototyping interactive systems, including advanced Logo variants, though Papert's primary focus remained on scaling constructionist tools for widespread educational adoption.[6]Later Educational and Policy Engagements

In the 1990s, Papert consulted on educational technology projects that extended his constructionist principles beyond academic settings, notably collaborating with the LEGO Group starting in 1989 to develop programmable robotics kits. This partnership culminated in the 1998 commercial release of LEGO Mindstorms, a system allowing children to program brick-based robots using a visual language inspired by Logo, thereby embedding hands-on computational thinking into physical construction activities.[1][29] Papert continued advocating for systemic school restructuring in the 1990s and 2000s, contending that conventional models reliant on age-segregated classrooms and teacher-directed instruction obstruct children's innate capacity for self-directed, causal exploration of ideas. In a 1997 paper published in the Journal of the Learning Sciences, he argued that genuine reform was untenable without dismantling entrenched structural barriers, such as rigid curricula and fragmented scheduling, which perpetuate superficial learning over deep conceptual mastery.[30] He specifically criticized age-based grouping as fostering isolation from diverse interactions essential for knowledge building, likening it in a 2001 interview to other forms of harmful segregation that limit social and intellectual development.[31] From 2005 onward, Papert played a key advisory role in the One Laptop per Child (OLPC) initiative, a nonprofit effort co-initiated by MIT Media Lab director Nicholas Negroponte to distribute $100 laptops to children in developing nations, explicitly promoting constructivist pedagogies through device-driven, child-led discovery. Papert's involvement helped shape OLPC's emphasis on laptops as "knowledge construction tools" rather than mere information delivery systems, influencing deployments in over 50 countries that reached millions of units by prioritizing software ecosystems for collaborative programming and problem-solving.[22][32]Core Theoretical and Practical Contributions

Invention and Evolution of Logo

Logo was developed in 1967 by Seymour Papert, Wally Feurzeig, and Cynthia Solomon at Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN), marking the first programming language explicitly designed for educational use with children in mind.[33][3] The initial implementation ran on systems like the PDP-1, emphasizing list processing and procedural programming inspired by Lisp, but adapted for accessibility through simple syntax and immediate feedback mechanisms.[33] A core innovation was the introduction of turtle graphics, where a virtual "turtle" serves as an on-screen cursor that executes movement commands to draw geometric shapes procedurally.[34] Key primitives includeFORWARD (or FD) to move the turtle ahead by a specified distance, TURN (or RT/LT for right/left) to rotate it by degrees, and REPEAT for looping instructions, enabling constructions like polygons via code such as REPEAT 4 [FORWARD 100 RIGHT 90] to form a square.[34][35] These elements supported empirical experimentation, as users could iteratively test and refine procedures by observing the turtle's path and adjusting parameters directly in an interactive environment.[36]

Over time, Logo evolved through variants that extended its core mechanics. In the 1980s, LogoWriter, released in 1985 by Logo Computer Systems Inc. (LCSI), integrated word processing capabilities with graphics, allowing text manipulation alongside turtle commands and support for multiple turtles.[37][38] By the 1990s, StarLogo emerged as a parallel extension for modeling complex systems, featuring multi-agent simulations where numerous turtles interact concurrently to demonstrate emergent behaviors, building on Logo's primitives for decentralized computation.[23] These iterations preserved the language's procedural foundation while incorporating hardware integrations, such as with LEGO for physical robotics, to expand graphical and simulation primitives.[23]