Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pipe cleaner

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2021) |

A pipe cleaner, otherwise referred to as a chenille stem, is a type of brush originally intended for removing moisture and residue from smoking pipes. They can also be used for any application that calls for cleaning out small bores or tight places. Special pipe cleaners are manufactured specifically for cleaning out medical apparatus and for engineering applications.

Outside of their originally intended purpose, they are commonly used in crafts, and are also popular for winding around bottle necks to catch drips, bundling things together, as a twist tie, colour-coding, and as a makeshift brush for applying paints, oils, solvents, greases, and similar substances.

Description

[edit]Smoking pipe cleaners normally use some absorbent material, usually cotton or sometimes viscose. Bristles of stiffer material, normally monofilament nylon or polypropylene are sometimes added to better scrub out what is being cleaned. Microfilament polyester is used in some technical pipe cleaners because polyester wicks liquid away rather than absorbing it as cotton does. Some smoking pipe cleaners are made conical or tapered so that one end is thick and one end thin. The thin end is for cleaning the small bore of the pipe stem and then the thick end for the bowl or the wider part of the stem. When used for cleaning purposes, pipe cleaners are normally discarded after one or two uses.

History

[edit]Pipe cleaners were invented by John Harry Stedman[1] and Charles Angel in Rochester, New York in the early 1900s, later to be sold on to BJ Long Company,[2][3] with a possibly parallel invention by Johan Petter Johansson 1923.[4][5]

Crafts

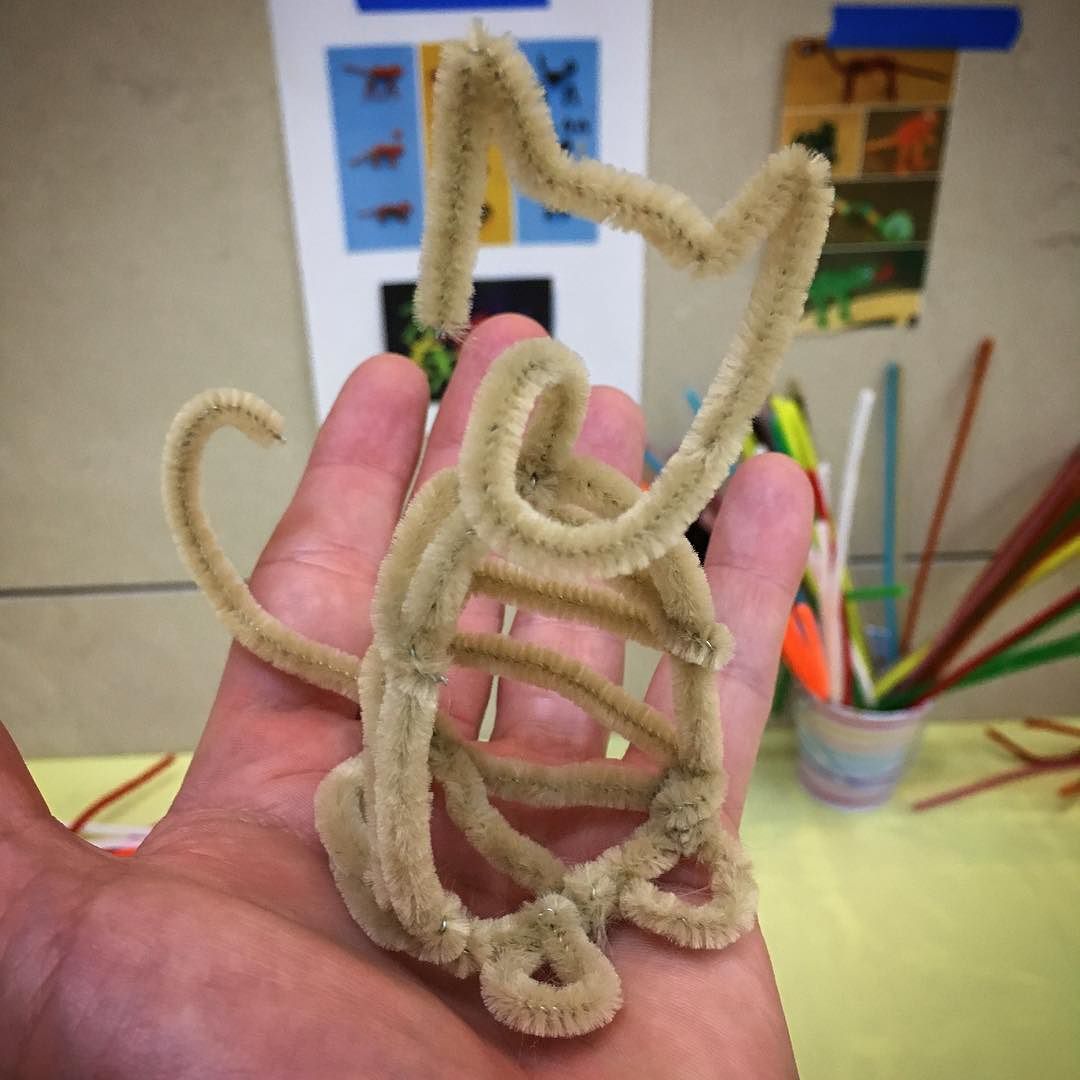

[edit]Pipe cleaners are commonly used in arts and crafts projects. Craft pipe cleaners are usually made with polyester or nylon pile and are often longer and thicker than the "cleaning" type, and available in many different colors. Craft pipe cleaners are not very useful for cleaning purposes, because the polyester does not absorb liquids, and the thicker versions may not even fit down the stem of a normal pipe or into the usual hard-to-access area of applications that call for cleaning small bores or tight places.

In Japan, crafting with pipe cleaners is known as Mogol art. Its name derived from the Portuguese word Mughal for a style of weaving.[6] Workshops in malls and schools in Japan have been led by Atushi Kitanaka on an effort to support the pipe cleaner industry. Ikuyo Fujita (藤田育代 Fujita Ikuyo) is a Japanese artist who works primarily in needle felt painting and mogol (pipe cleaner) art. Use of pipe cleaners as an art format where animals [7] are made by twisting pipe cleaners together. They can also be used to create whiskers for an animal mask or nose.

Craft pipe cleaners are often used in classroom settings for a variety of reasons including creating simple models,[8] creating complex models,[9] or as learning aids for various topics.[10]

Manufacture

[edit]A pipe cleaner is made of two lengths of wire, called the core, twisted together trapping short lengths of fibre between them, called the pile. Pipe cleaners are usually made two at a time, as the inner wires of each pipe cleaner have the yarn wrapped around them, making a coil, the outer wires trap the wraps of yarn, which are then cut, making the tufts. Chenille yarn is made in much the same way, which is why craft pipe cleaners are often called "chenille stems". The word "chenille" comes from French meaning "caterpillar". Some pipe cleaner machines are actually converted chenille machines. Some machines produce very long pipe cleaners which are wound onto spools. The spools may be sold as-is or cut to length depending on the intended use. Other machines cut the pipe cleaners to length as they come off the machines. Smoking pipe cleaners are usually 15–17 cm (5.9–6.7 in) long. Craft ones are often 30 cm (12 in) and can be up to 50 cm (20 in). They come in 4 mm, 6 mm, and 15 mm diameter sizes.[11] Jumbo pipe cleaners have a 30 mm diameter with lengths of 45 cm (18 in) and 2 metres (6.6 feet).

References

[edit]- ^ "John Harry Stedman". Rochwiki.org.

- ^ "History of pipe cleaners". Rebornpipes.com. 5 July 2013.

- ^ Gregory R. Foster. "JOHN HARRY STEDMAN : HIS BUSY LIFE AND WEIRD INVENTIONS" (PDF). Lib.rochester.edu. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "Johan Petter Johansson – Skiftnyckeln". Svensktuppfinnaremuseum.se. July 2010.

- ^ "Bibliotek Mellansjö katalog › Detaljer för: Johan Petter Johansson 1853-1943 : uppfinnare från Vårgårda; tröskverk 1887, rörtång 1888, klövernötningsmaskin 1890, skiftnyckel 1892, sockertång 1909, piprensare 1923 (totalt 118 patent) /". Bibliotekmellansjo.se. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "Mogol art". Craftjam.jp. Archived from the original on 2021-06-29. Retrieved 2021-08-12.

- ^ "Pipe cleaner artist". News.yahoo.com. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 2021-08-12.

- ^ Cocke, Teri E.; Geest, Emily A; Shufran, Andrine A (2022). "Learning about mosquitoes, diseases, and vectors: a classroom activity". Science Activities. 59 (3): 142–150. doi:10.1080/00368121.2022.2071816. S2CID 250191197.

- ^ Yu, Christine I.; Husmann, Polly R. (2021-06-01). "Construction of Knowledge Through Doing: A Brachial Plexus Model from Pipe Cleaners". Medical Science Educator. 31 (3): 1053–1064. doi:10.1007/s40670-021-01274-2 (inactive 18 November 2025). ISSN 2156-8650. PMC 8368674. PMID 34457949.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2025 (link) - ^ Halverson, Kristy L. (2010-04-01). "Using Pipe Cleaners to Bring the Tree of Life to Life". The American Biology Teacher. 72 (4): 223–224. doi:10.1525/abt.2010.72.4.4. ISSN 0002-7685. S2CID 85748995.

- ^ "Kwik Crafts: Pipe Cleaners". Kwikcrafts.com. Archived from the original on 2023-03-08. Retrieved 2021-08-12.

External links

[edit] Media related to Pipe cleaners at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pipe cleaners at Wikimedia Commons