Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Plasma display

View on Wikipedia

A plasma display panel is a type of flat-panel display that uses small cells containing plasma: ionized gas that responds to electric fields. Plasma televisions were the first large (over 32 inches/81 cm diagonal) flat-panel displays to be released to the public.

Until about 2007, plasma displays were commonly used in large televisions. By 2013, they had lost nearly all market share due to competition from low-cost liquid-crystal displays (LCDs). Manufacturing of plasma displays for the United States retail market ended in 2014,[1][2] and manufacturing for the Chinese market ended in 2016.[3][4] Plasma displays are obsolete, having been superseded in most if not all aspects by OLED displays.[5]

Competing display technologies include cathode-ray tube (CRT), organic light-emitting diode (OLED), CRT projectors, AMLCD, digital light processing (DLP), SED-tv, LED display, field emission display (FED), and quantum dot display (QLED).

History

[edit]Early development

[edit]

Kálmán Tihanyi, a Hungarian engineer, described a proposed flat-panel plasma display system in a 1936 paper.[7]

The first practical plasma video display was co-invented in 1964 at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign by Donald Bitzer, H. Gene Slottow, and graduate student Robert Willson for the PLATO computer system.[8][9] The goal was to create a display that had inherent memory to reduce the cost of the terminals.[10] The original neon orange monochrome Digivue display panels built by glass producer Owens-Illinois were very popular in the early 1970s because they were rugged and needed neither memory nor circuitry to refresh the images.[11] A long period of sales decline occurred in the late 1970s because semiconductor memory made CRT displays cheaper than the $2500 USD 512 × 512 PLATO plasma displays.[12] Nevertheless, the plasma displays' relatively large screen size and 1 inch (25.4 mm) thickness made them suitable for high-profile placement in lobbies and stock exchanges.

Burroughs Corporation, a maker of adding machines and computers, developed the Panaplex display in the early 1970s. The Panaplex display, generically referred to as a gas-discharge or gas-plasma display,[13] uses the same technology as later plasma video displays, but began life as a seven-segment display for use in adding machines. They became popular for their bright orange luminous look and found nearly ubiquitous use throughout the late 1970s and into the 1990s in cash registers, calculators, pinball machines, aircraft avionics such as radios, navigational instruments, and stormscopes; test equipment such as frequency counters and multimeters; and generally anything that previously used nixie tube or numitron displays with a high digit-count. These displays were eventually replaced by LEDs because of their low current-draw and module-flexibility, but are still found in some applications where their high brightness is desired, such as pinball machines and avionics.

1980s

[edit]

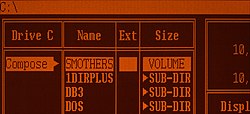

In 1983, IBM introduced a 19-inch (48 cm) orange-on-black monochrome display (Model 3290 Information Panel) which was able to show up to four simultaneous IBM 3270 terminal sessions.[14] By the end of the decade, orange monochrome plasma displays were used in a number of high-end AC-powered portable computers, such as the Ericsson Portable PC (the first use of such a display in 1985),[15] the Compaq Portable 386 (1987) and the IBM P75 (1990). Plasma displays had a better contrast ratio, viewability angle, and less motion blur than the LCDs that were available at the time, and were used until the introduction of active-matrix color LCD displays in 1992.[14]

Due to heavy competition from monochrome LCDs used in laptops and the high costs of plasma display technology, in 1987 IBM planned to shut down its factory in Kingston, New York, the largest plasma plant in the world, in favor of manufacturing mainframe computers, which would have left development to Japanese companies.[16] Dr. Larry F. Weber, a University of Illinois ECE PhD (in plasma display research) and staff scientist working at CERL (home of the PLATO System), co-founded Plasmaco with Stephen Globus and IBM plant manager James Kehoe, and bought the plant from IBM for US$50,000. Weber stayed in Urbana as CTO until 1990, then moved to upstate New York to work at Plasmaco.

1990s

[edit]In 1992, Fujitsu introduced the world's first 21-inch (53 cm) full-color display. It was based on technology created at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign and NHK Science & Technology Research Laboratories.

In 1994, Weber demonstrated a color plasma display at an industry convention in San Jose. Panasonic Corporation began a joint development project with Plasmaco, which led in 1996 to the purchase of Plasmaco, its color AC technology, and its American factory for US$26 million.

In 1995, Fujitsu introduced the first 42-inch (107 cm) plasma display panel;[17][18] it had 852×480 resolution and was progressively scanned.[19] Two years later, at the Customer Electronics Show 1997 and CeBIT, Philips introduced the first large commercially available flat-panel TV, using the Fujitsu panels. Philips had plans to sell it for 70,000 french francs.[20][21][22] It was released as the Philips 42PW9962, and available at four Sears locations in the United States, for the price of $14,999,[23] including in-home installation. Pioneer and Fujitsu[24] also began selling plasma televisions that year, and other manufacturers followed. By the year 2000 prices had dropped to $10,000.

2000s

[edit]

In the year 2000, the first 60-inch (152-cm) plasma display was developed by Plasmaco. Panasonic was also reported to have developed a process to make plasma displays using ordinary window glass instead of the much more expensive "high strain point" glass.[25] High strain point glass is made similarly to conventional float glass, but it is more heat resistant, deforming at higher temperatures. High strain point glass is normally necessary because plasma displays have to be baked during manufacture to dry the rare-earth phosphors after they are applied to the display. However, high strain point glass may be less scratch resistant.[26][27][28][29]

Until the early 2000s, plasma displays were the most popular choice for HDTV flat-panel display as they had many benefits over LCDs. Beyond plasma's deeper blacks, increased contrast, faster response time, greater color spectrum, and wider viewing angle; they were also much bigger than LCDs, and it was believed that LCDs were suited only to smaller sized televisions. Plasma had overtaken rear-projection systems in 2005.[30]

However, improvements in LCD fabrication narrowed the technological gap. The increased size, lower weight, falling prices, and often lower electrical power consumption of LCDs made them competitive with plasma television sets. In 2006, LCD prices started to fall rapidly and their screen sizes increased, although plasma televisions maintained a slight edge in picture quality and a price advantage for sets at the critical 42" size and larger. By late 2006, several vendors were offering 42" LCDs, albeit at a premium price, encroaching upon plasma's only stronghold. More decisively, LCDs offered higher resolutions and true 1080p support, while plasmas were stuck at 720p, which made up for the price difference.[31]

In late 2006, analysts noted that LCDs had overtaken plasmas, particularly in the 40-inch (100 cm) and above segment where plasma had previously gained market share.[32] Another industry trend was the consolidation of plasma display manufacturers, with around 50 brands available but only five manufacturers. In the first quarter of 2008, a comparison of worldwide TV sales broke down to 22.1 million for direct-view CRT, 21.1 million for LCD, 2.8 million for plasma, and 0.1 million for rear projection.[33]

When the sales figures for the 2007 Christmas season were finally tallied, analysts were surprised to find that not only had LCD outsold plasma, but CRTs as well, during the same period.[34] This development drove competing large-screen systems from the market almost overnight. The February 2009 announcement that Pioneer Electronics was ending production of plasma screens was widely considered the tipping point in the technology's history as well.[35]

Screen sizes have increased since the introduction of plasma displays. The largest plasma video display in the world at the 2008 Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Nevada, was a 150-inch (380 cm) unit manufactured by Matsushita Electric Industrial (Panasonic) standing 6 ft (180 cm) tall by 11 ft (340 cm) wide.[36][37]

2010s

[edit]At the 2010 Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Panasonic introduced their 152" 2160p 3D plasma. In 2010, Panasonic shipped 19.1 million plasma TV panels.[38]

In 2010, the shipments of plasma TVs reached 18.2 million units globally.[39] Since that time, shipments of plasma TVs have declined substantially. This decline has been attributed to the competition from liquid crystal (LCD) televisions, whose prices have fallen more rapidly than those of the plasma TVs.[40] In late 2013, Panasonic announced that they would stop producing plasma TVs from March 2014 onwards.[41] In 2014, LG and Samsung discontinued plasma TV production as well,[42][43] effectively killing the technology, probably because of declining demand.

Design

[edit]

A panel of a plasma display typically comprises millions of tiny compartments in between two panels of glass. These compartments, or "bulbs" or "cells", hold a mixture of noble gases and a minuscule amount of another gas (e.g., mercury vapor). Just as in the fluorescent lamps over an office desk, when a high voltage is applied across the cell, the gas in the cells forms a plasma. With flow of electricity (electrons), some of the electrons strike mercury particles as the electrons move through the plasma, momentarily increasing the energy level of the atom until the excess energy is shed. Mercury sheds the energy as ultraviolet (UV) photons. The UV photons then strike phosphor that is painted on the inside of the cell. When the UV photon strikes a phosphor molecule, it momentarily raises the energy level of an outer orbit electron in the phosphor molecule, moving the electron from a stable to an unstable state; the electron then sheds the excess energy as a photon at a lower energy level than UV light; the lower energy photons are mostly in the infrared range but about 40% are in the visible light range. Thus the input energy is converted to mostly infrared but also as visible light. The screen heats up to between 30 and 41 °C (86 and 106 °F) during operation. Depending on the phosphors used, different colors of visible light can be achieved. Each pixel in a plasma display is made up of three cells comprising the primary colors of visible light. Varying the voltage of the signals to the cells thus allows different perceived colors.

The long electrodes are stripes of electrically conducting material that also lies between the glass plates in front of and behind the cells. The "address electrodes" sit behind the cells, along the rear glass plate, and can be opaque. The transparent display electrodes are mounted in front of the cell, along the front glass plate. As can be seen in the illustration, the electrodes are covered by an insulating protective layer.[44] A magnesium oxide layer may be present to protect the dielectric layer and to emit secondary electrons.[45][46]

Control circuitry charges the electrodes that cross paths at a cell, creating a voltage difference between front and back. Some of the atoms in the gas of a cell then lose electrons and become ionized, which creates an electrically conducting plasma of atoms, free electrons, and ions. The collisions of the flowing electrons in the plasma with the inert gas atoms leads to light emission; such light-emitting plasmas are known as glow discharges.[47][48][49]

In a monochrome plasma panel, the gas is mostly neon, and the color is the characteristic orange of a neon-filled lamp (or sign). Once a glow discharge has been initiated in a cell, it can be maintained by applying a low-level voltage between all the horizontal and vertical electrodes–even after the ionizing voltage is removed. To erase a cell all voltage is removed from a pair of electrodes. This type of panel has inherent memory. A small amount of nitrogen is added to the neon to increase hysteresis and thus help with the memory effect.[10] Plasma panels may be built without nitrogen gas, using xenon, neon, argon, and helium instead with mercury being used in some early displays.[50][51] In color panels, the back of each cell is coated with a phosphor. The ultraviolet photons emitted by the plasma excite these phosphors, which give off visible light with colors determined by the phosphor materials. This aspect is comparable to fluorescent lamps and to the neon signs that use colored phosphors.

Every pixel is made up of three separate subpixel cells, each with different colored phosphors. One subpixel has a red light phosphor, one subpixel has a green light phosphor and one subpixel has a blue light phosphor. These colors blend together to create the overall color of the pixel, the same as a triad of a shadow mask CRT or color LCD. Plasma panels use pulse-width modulation (PWM) to control brightness: by varying the pulses of current flowing through the different cells thousands of times per second, the control system can increase or decrease the intensity of each subpixel color to create billions of different combinations of red, green and blue. In this way, the control system can produce most of the visible colors. Plasma displays use the same phosphors as CRTs, which accounts for the extremely accurate color reproduction when viewing television or computer video images (which use an RGB color system designed for CRT displays).

To produce light, the cells need to be driven at a relatively high voltage (~300 volts) and the pressure of the gases inside the cell needs to be low (~500 torr).[52]

Plasma displays have a wide color gamut and can be produced in fairly large sizes—up to 3.8 metres (150 in) diagonally. They had a very low luminance "dark-room" black level compared with the lighter grey of the unilluminated parts of an LCD screen. (As plasma panels are locally lit and do not require a back light, blacks are blacker on plasma and grayer on LCDs.)[53] LED-backlit LCD televisions have been developed to reduce this distinction. The display panel itself is about 6 cm (2.4 in) thick, generally allowing the device's total thickness (including electronics) to be less than 10 cm (3.9 in). Power consumption varies greatly with picture content, with bright scenes drawing significantly more power than darker ones – this is also true for CRTs as well as modern LCDs where LED backlight brightness is adjusted dynamically. The plasma that illuminates the screen can reach a temperature of at least 1,200 °C (2,190 °F). Typical power consumption is 400 watts for a 127 cm (50 in) screen. Most screens are set to "vivid" mode by default in the factory (which maximizes the brightness and raises the contrast so the image on the screen looks good under the extremely bright lights that are common in big box stores), which draws at least twice the power (around 500–700 watts) of a "home" setting of less extreme brightness.[54] The lifetime of the latest[as of?] generation of plasma displays is estimated at 100,000 hours (11 years) of actual display time, or 27 years at 10 hours per day. This is the estimated time over which maximum picture brightness degrades to half the original value.[55]

Plasma screens are made out of glass, which may result in glare on the screen from nearby light sources. Plasma display panels cannot be economically manufactured in screen sizes smaller than 82 centimetres (32 in).[56][57] Although a few companies have been able to make plasma enhanced-definition televisions (EDTV) this small, even fewer have made 32-inch (81-cm) plasma HDTVs. With the trend toward large-screen television technology, the 32-inch (81-cm) screen size was rapidly disappearing by mid-2009. Though considered bulky and thick compared with their LCD counterparts, some sets such as Panasonic's Z1 and Samsung's B860 series are as slim as 2.5 cm (1 in) thick making them comparable to LCDs in this respect. Plasma displays are generally heavier than LCD and may require more careful handling, such as being kept upright.[citation needed]

Plasma displays use more electrical power, on average, than an LCD TV using a LED backlight. Older CCFL backlights for LCD panels used quite a bit more power, and older plasma TVs used quite a bit more power than recent models.[58][59]

Plasma displays do not work as well at high altitudes above 6,500 feet (2,000 meters)[60] due to pressure differential between the gases inside the screen and the air pressure at altitude. It may cause a buzzing noise. Manufacturers rate their screens to indicate the altitude parameters.[60]

For those who wish to listen to AM radio, or are amateur radio operators (hams) or shortwave listeners (SWL), the radio frequency interference (RFI) from these devices can be irritating or disabling.[61]

In their heyday, they were less expensive for the buyer per square inch than LCD, particularly when considering equivalent performance.[62]

Plasma displays have wider viewing angles than those of LCD; images do not suffer from degradation at less than straight ahead angles like LCDs. LCDs using IPS technology have the widest angles, but they do not equal the range of plasma primarily due to "IPS glow", a generally whitish haze that appears due to the nature of the IPS pixel design.[63][64]

Plasma displays have less visible motion blur, thanks in large part to very high refresh rates and a faster response time, contributing to superior performance when displaying content with significant amounts of rapid motion such as auto racing, hockey, baseball, etc.[63][64][65][66]

Plasma displays have superior uniformity to LCD panel backlights, which nearly always produce uneven brightness levels, although this is not always noticeable. High-end computer monitors have technologies to try to compensate for the uniformity problem.[67][68]

Contrast ratio

[edit]Contrast ratio is the difference between the brightest and darkest parts of an image, measured in discrete steps, at any given moment. Generally, the higher the contrast ratio, the more realistic the image is (though the "realism" of an image depends on many factors including color accuracy, luminance linearity, and spatial linearity). Contrast ratios for plasma displays are often advertised as high as 5,000,000:1.[69] On the surface, this is a significant advantage of plasma over most other current display technologies, a notable exception being organic light-emitting diode. Although there are no industry-wide guidelines for reporting contrast ratio, most manufacturers follow either the ANSI standard or perform a full-on-full-off test. The ANSI standard uses a checkered test pattern whereby the darkest blacks and the lightest whites are simultaneously measured, yielding the most accurate "real-world" ratings. In contrast, a full-on-full-off test measures the ratio using a pure black screen and a pure white screen, which gives higher values but does not represent a typical viewing scenario. Some displays, using many different technologies, have some "leakage" of light, through either optical or electronic means, from lit pixels to adjacent pixels so that dark pixels that are near bright ones appear less dark than they do during a full-off display. Manufacturers can further artificially improve the reported contrast ratio by increasing the contrast and brightness settings to achieve the highest test values. However, a contrast ratio generated by this method is misleading, as content would be essentially unwatchable at such settings.[70][71][72]

Each cell on a plasma display must be precharged before it is lit, otherwise the cell would not respond quickly enough. Precharging normally increases power consumption, so energy recovery mechanisms may be in place to avoid an increase in power consumption.[73][74][75] This precharging means the cells cannot achieve a true black,[76] whereas an LED backlit LCD panel can actually turn off parts of the backlight, in "spots" or "patches" (this technique, however, does not prevent the large accumulated passive light of adjacent lamps, and the reflection media, from returning values from within the panel). Some manufacturers have reduced the precharge and the associated background glow, to the point where black levels on modern plasmas are starting to become close to some high-end CRTs Sony and Mitsubishi produced ten years before the comparable plasma displays. With an LCD, black pixels are generated by a light polarization method; many panels are unable to completely block the underlying backlight. More recent LCD panels using LED illumination can automatically reduce the backlighting on darker scenes, though this method cannot be used in high-contrast scenes, leaving some light showing from black parts of an image with bright parts, such as (at the extreme) a solid black screen with one fine intense bright line. This is called a "halo" effect which has been minimized on newer LED-backlit LCDs with local dimming. Edgelit models cannot compete with this as the light is reflected via a light guide to distribute the light behind the panel.[63][64][77]

Plasma displays are capable of producing deeper blacks than LCD allowing for a superior contrast ratio.[63][64][77]

Earlier generation displays (circa 2006 and prior) had phosphors that lost luminosity over time, resulting in gradual decline of absolute image brightness. Newer models have advertised lifespans exceeding 100,000 hours (11 years), far longer than older CRTs.[55][77]

Screen burn-in

[edit]

Image burn-in occurs on CRTs and plasma panels when the same picture is displayed for long periods. This causes the phosphors to overheat, losing some of their luminosity and producing a "shadow" image that is visible with the power off. Burn-in is especially a problem on plasma panels because they run hotter than CRTs. Early plasma televisions were plagued by burn-in, making it impossible to use video games or anything else that displayed static images.

Plasma displays also exhibit another image retention issue which is sometimes confused with screen burn-in damage. In this mode, when a group of pixels are run at high brightness (when displaying white, for example) for an extended period, a charge build-up in the pixel structure occurs and a ghost image can be seen. However, unlike burn-in, this charge build-up is transient and self-corrects after the image condition that caused the effect has been removed and a long enough period has passed (with the display either off or on).

Plasma manufacturers have tried various ways of reducing burn-in such as using gray pillarboxes, pixel orbiters and image washing routines. Recent models have a pixel orbiter that moves the entire picture slower than is noticeable to the human eye, which reduces the effect of burn-in but does not prevent it.[78] None to date have eliminated the problem and all plasma manufacturers continue to exclude burn-in from their warranties.[77][79]

Screen resolution

[edit]Fixed-pixel displays such as plasma TVs scale the video image of each incoming signal to the native resolution of the display panel. The most common native resolutions for plasma display panels are 852×480 (EDTV), 1,366×768 and 1920×1080 (HDTV). As a result, picture quality varies depending on the performance of the video scaling processor and the upscaling and downscaling algorithms used by each display manufacturer.[80][81]

Early plasma televisions were enhanced-definition (ED) with a native resolution of 840×480 (discontinued) or 852×480 and down-scaled their incoming high-definition video signals to match their native display resolutions.[82]

The following ED resolutions were common prior to the introduction of HD displays, but have long been phased out in favor of HD displays, as well as because the overall pixel count in ED displays is lower than the pixel count on SD PAL displays (852×480 vs 720×576, respectively).

- 840×480p

- 852×480p

Early high-definition (HD) plasma displays had a resolution of 1024x1024 and were alternate lighting of surfaces (ALiS) panels made by Fujitsu and Hitachi.[83][84] These were interlaced displays, with non-square pixels.[85]

Later HDTV plasma televisions usually have a resolution of 1,024×768 found on many 42-inch (107-cm) plasma screens, 1280×768 and 1,366×768 found on 50 in, 60 in, and 65 in plasma screens, or 1920×1080 found on plasma screen sizes from 42 to 103 inches (107–262 cm). These displays are usually progressive displays, with non-square pixels, and will up-scale and de-interlace their incoming standard-definition signals to match their native display resolutions. 1024×768 resolution requires that 720p content be downscaled in one direction and upscaled in the other.[86][87]

Notable manufacturers

[edit]- Fujitsu (only produced panels[88])

- Chunghwa Picture Tubes (only produced panels [89])

- Formosa plastics (only produced panels[90])

- Hitachi (produced panels[91])

- LG (produced panels[92])

- Panasonic Viera (produced panels[1][2][93][94])

- Pioneer (produced panels[95])

- Samsung (produced panels[96])

- Toshiba (produced panels[97])

Environmental impact

[edit]Plasma screens use significantly more energy than CRT and LCD screens.[98]

See also

[edit]- History of display technology

- Plasmatron

- Large-screen television technology – Technology rapidly developed in the late 1990s and 2000s

- Comparison of CRT, LCD, Plasma, and OLED

References

[edit]- ^ a b Michael Hiltzik (July 7, 2014). "Farewell to the big-screen plasma TV". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 20, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ a b "Panasonic in talks to sell Hyogo plasma factory". January 28, 2014. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved December 19, 2019 – via Japan Times Online.

- ^ O'Toole, David Goldman and James (30 October 2014). "The world is running out of plasma TVs". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ Archer, John. "OLED TV Thrashes Plasma TV In New Public Shoot Out". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2016-11-07. Retrieved 2017-09-08.

- ^ "4K OLED TV Lays Plasma Ghost to Rest; Panasonic Pips LG". Archived from the original on 2021-01-27. Retrieved 2020-12-24.

- ^ Google books – Michael Allen's 2008 E-Learning Annual By Michael W. Allen Archived 2023-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Kalman Tihanyi's plasma television" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-26. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- ^ "Bitzer Wins Emmy Award for Plasma Screen Technology". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ^ "ECE Alumni wins award for inventing the flat-panel plasma display". Oct 23, 2002. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved Jan 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Weber, Larry F. (April 2006). "History of the Plasma Display Panel". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science. 34 (2): 268–278. Bibcode:2006ITPS...34..268W. doi:10.1109/TPS.2006.872440.

- ^ Brian Dear, Chapter 6 – Gas and Glass, The Friendly Orange Glow, Pantheon Books, New York, 2017; pages 92–111 cover the development and first stages AC plasma panel commercialization.

- ^ Brian Dear, Chapter 22 – The Business Opportunity, The Friendly Orange Glow, Pantheon Books, New York, 2017; pages 413–417 cover CDC's decision to use CRTs with cheap video-RAM instead of plasma panels in 1975.

- ^ "What is gas-plasma display?". Webopedia. September 1996. Archived from the original on 2009-10-15. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ^ a b "The chronicles of gas-plasma". Retropaq.com. 20 October 2020. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ^ News:New Products:The Ericsson Portable PC, InfoWorld, 22 Apr 1985, Page 26

- ^ Ogg, E., "Getting a charge out of plasma TV" Archived 2013-11-03 at the Wayback Machine, CNET News, June 18, 2007, retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ^ Thurber, David (August 25, 1995). "Flat screen TVs coming soon to a wall near you". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. p. 9C. Archived from the original on November 1, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ Weber, L. F., "History of the Plasma Display Panel," IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science, Vol. 34, No. 2, (April, 2006), pp.268-278.

- ^ Mendrala, Jim, "Flat Panel Plasma Display" Archived 2019-01-05 at the Wayback Machine, North West Tech Notes, No. 4, June 15, 1997, retrieved 2009-01-29.

- ^ "Philips et Thomson en position d'attente". 9 April 1997. Archived from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ "20 Jahre Flachbildfernseher - OLED und 4K momentan Spitze der Entwicklung". Archived from the original on 2023-02-28. Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- ^ "Fujitsu is World's First to Mass Produce 42-inch Color Plasma Display Panels". Archived from the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- ^ "Sept 19 1999". The Central New Jersey Home News. 19 September 1999. p. 348. Archived from the original on 2024-01-28. Retrieved 2024-01-28.

- ^ "The Consumer Electronics Hall of Fame: Fujitsu Plasma TV". Archived from the original on 2023-02-28. Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- ^ "Passion for Plasma Fuels Creation of First 60-Inch Flat-Screen TV". The Wall Street Journal. 30 August 2000. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ "Central Glass to produce speciality glass". 19 November 2002. Archived from the original on 5 November 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2020.

- ^ "High Strain-Point Glass Composition for Substrate". Archived from the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- ^ "Baking system for plasma display panel and layout method for said system". Archived from the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- ^ Duisit, G., Gaume, O., & El Khiati, N. (2003). 23.4: High Strain Point Glass with Improved Chemical Stability and Mechanical Properties for FPDs. SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers, 34(1), 905. doi:10.1889/1.1832431

- ^ "Plasma TV sales overtake projection units, says report" Archived 2010-01-05 at the Wayback Machine EETimes, 17 August 2005

- ^ Reuters, "Shift to large LCD TVs over plasma", MSNBC, 27 November 2006

- ^ "Shift to large LCD TVs over plasma", MSNBC, November 27, 2006, retrieved 2007-08-12.

- ^ "LCD televisions outsell plasma 8 to 1 worldwide" Archived 2009-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, Digital Home, 21 May 2008, retrieved 2008-06-13.

- ^ Gruener, Wolfgang (19 February 2008). "LCD TVs outship CRT TVs for the first time". TG Daily. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008.

- ^ Jose Fermoso, "Pioneer's Kuro Killing: A Tipping Point in the Plasma Era" Archived 2010-07-16 at the Wayback Machine, newteevee.com, 21 February 2009

- ^ Dugan, Emily., "6ft by 150 inches – and that's just the TV" Archived 2015-09-25 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 8 January 2008, retrieved 2009-01-29.

- ^ PCMag.com – Panasonic's 150-Inch "Life Screen" Plasma Opens CES Archived 2017-02-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Panasonic celebrates higher plasma TV sales for 2010, sets prices for 2011". EnGadget. March 1, 2011. Archived from the original on July 3, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ LCD TV Market Ten Times Larger Than Plasma TVs On Units-Shipped Basis Archived 2011-10-13 at the Wayback Machine, 20 February 2011, Jonathan Sutton, hdtvtest.co.uk, retrieved at September 12, 2011

- ^ "LCD TV Growth Improving, As Plasma and CRT TV Disappear, According to NPD DisplaySearch". PRWeb. April 16, 2014. Archived from the original on September 4, 2014. Retrieved August 31, 2014.

Of course, the growth of LCD comes at the expense of plasma and CRT TV shipments, which are forecast to fall 48 percent and 50 percent, respectively, in 2014. In fact, both technologies will all but disappear by the end of 2015, as manufacturers cut production of both technologies in order to focus on LCD, which has become more competitive from a cost standpoint.

- ^ "TV shoppers: Now is the time to buy a Panasonic plasma". CNET. October 31, 2013. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ Will Greenwald (October 28, 2014). "With LG Out, Plasma HDTVs Are Dead". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ David Katzmaier (July 2, 2014). "Samsung to end plasma TV production this year". CNET. Archived from the original on April 27, 2020. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Weber, Larry F. (April 2006). "History of the plasma display panel". IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science. 34 (2): 268–278. Bibcode:2006ITPS...34..268W. doi:10.1109/TPS.2006.872440. S2CID 20290119.

All plasma TVs on the market today have the same features that were demonstrated in the first plasma display which was a device with only a single cell. These features include alternating sustain voltage, dielectric layer, wall charge, and a neon-based gas mixture.

Paid access. - ^ Naoi, Taro; Lin, Hai; Otani, Eishiro; Ito, Hiroshi; Corp, Panasonic (15 July 2011). "Plasma display panel having an MGO crystal layer for improved discharge characteristics and method of manufacturing same". Archived from the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- ^ "Plasma display panel comprising magnesium oxide protective layer". Archived from the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- ^ Myers, Robert L. (2002). Display interfaces: fundamentals and standards. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-471-49946-6. Archived from the original on 2024-01-28. Retrieved 2016-10-16.

Plasma displays are closely related to the simple neon lamp.

- ^ "How Plasma Displays Work". HowStuffWorks. 19 March 2002. Archived from the original on 16 June 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ Yen, William M.; Shionoya, Shigeo; Yamamoto, Hajime (2007). Phosphor handbook. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-3564-8.

- ^ "Information Display". Society for Information Display. September 21, 2008 – via Google Books.

- ^ Castellano, Joseph A. (December 2, 2012). Handbook of Display Technology. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-091724-5 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Aluminosilicate glass for flat display devices". Archived from the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- ^ HDGuru.com – Choosing The HDTV That’s Right For You Archived 2016-09-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ PlasmaTelevisions.org – How to Calibrate Your Plasma TV

- ^ a b PlasmaTVBuyingGuide.com – How Long Do Plasma TVs Last? Archived 2016-02-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Smith, Tony. "LG launches 'world's smallest' plasma TV". www.theregister.com. Archived from the original on 2021-03-04. Retrieved 2020-12-24.

- ^ "Review: Vizio VP322, the world's smallest plasma". CNET. Archived from the original on 2023-06-19. Retrieved 2023-06-19.

- ^ "LCD vs Plasma TVs". Which?. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ LED LCD vs. plasma vs. LCD Archived 2020-04-07 at the Wayback Machine, 2013

- ^ a b plasmatvbuyingguide.com - Plasma TVs at Altitude Archived 2016-02-19 at the Wayback Machine, 2012

- ^ "Plasma TV – Mother of All RFI Producers". www.eham.net. Archived from the original on 2018-09-29. Retrieved 2010-01-04.

- ^ "Sound Advice: Plasma TV sets are better, cheaper". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-09-30.

- ^ a b c d CNET Australia – Plasma vs. LCD: Which is right for you? Archived 2014-01-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d "LED-LCD vs. Plasma". Crutchfield. Archived from the original on 2021-05-31. Retrieved 2023-06-19.

- ^ Google books – Principles of Multimedia By Ranjan Parekh, Ranjan Archived 2023-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Google books – The electronics handbook By Jerry C. Whitaker Archived 2023-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "A plasma lover's guide to LED LCD". CNET. Archived from the original on 2023-06-19. Retrieved 2023-06-19.

- ^ "Dell U3014 Review - TFT Central". www.tftcentral.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2017-12-14. Retrieved 2014-09-30.

- ^ "Official Panasonic Store - Research and Buy Cameras, Headphones, Appliances, Shavers, Beauty products, and More". www.panasonic.net. Archived from the original on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- ^ Google books – Digital Signage Broadcasting By Lars-Ingemar Lundström Archived 2023-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Google books – Instrument Engineers' Handbook: Process control and optimization By Béla G. Lipták Archived 2023-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Google books – Computers, Software Engineering, and Digital Devices By Richard C. Dorf Archived 2023-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Plasma display device". Archived from the original on 2021-10-24. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- ^ "Gas panel with improved circuit for display operation". Archived from the original on 2021-10-24. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- ^ "Control of a plasma display panel". Archived from the original on 2021-10-24. Retrieved 2020-11-01.

- ^ "Replacing the CRT III". 2 November 2008. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d HomeTheaterMag.com – Plasma Vs. LCD Archived 2009-09-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Pixel Orbiter". Archived from the original on 2012-07-18. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- ^ PlasmaTVBuyingGuide.com – Plasma TV Screen Burn-In: Is It Still a Problem? Archived 2019-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Step 3: Is a 1080p Resolution Plasma TV Worth the Extra Money? Archived 2016-01-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Native Resolution Archived 2010-01-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ EDTV Plasma vs. HDTV Plasma Archived 2016-02-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ CNET UK – ALiS (alternate lighting of surfaces) Archived 2010-04-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Google Books – Newnes Guide to Television and Video Technology By K. F. Ibrahim, Eugene Trundle Archived 2023-04-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ PlasmaTVBuyingGuide.com – 1024 x 1024 Resolution Plasma Display Monitors vs.853 x 480 Resolution Plasma Display Monitors Archived 2016-02-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ About.com – Are All Plasma Televisions HDTVs? Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Practical Home Theater Guide – Plasma TV FAQs Archived 2016-12-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Eugene Register-Guard - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Archived from the original on 2023-04-13. Retrieved 2023-06-19.

- ^ "Chunghwa Picture Tubes, Ltd". www.encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 2020-01-12. Retrieved 2020-01-12.

- ^ Dean, Jason (June 5, 2003). "Formosa Plastics Enters Plasma-Display Market". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 12, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2020 – via www.wsj.com.

- ^ Osawa, Juro (January 23, 2012). "Hitachi to Shut Its Last TV Factory". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 8, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2020 – via www.wsj.com.

- ^ Mead, Rob (20 May 2007). "LG shuts plasma TV plant". TechRadar. Archived from the original on 2020-05-08. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- ^ "In Panasonic's plasma exit, Japan's TV makers come to terms with defeat". Reuters. 9 October 2013. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2020 – via mobile.reuters.com.

- ^ "Panasonic completes Amagasaki PDP plant". December 23, 2009. Archived from the original on May 8, 2020. Retrieved January 4, 2020 – via Japan Times Online.

- ^ "Pioneer puts new PDP factory on hold after poor sales". www.networkworld.com. Archived from the original on 2020-05-08. Retrieved 2020-01-04.

- ^ "You think that's a big TV factory? This is a big TV factory..." www.whathifi.com. 4 December 2008. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ "Toshiba phases out plasma displays". December 28, 2004.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Do flat-screen TVs eat more energy?". news.bbc.co.uk. 7 December 2006. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

External links

[edit]- Plasma display panels: The colorful history of an Illinois technology' ' by Jamie Hutchinson, Electrical and Computer Engineering Alumni News, Winter 2002–2003 (via archive.org)

- NYTimes.com – Forget L.C.D.; Go for Plasma, Says Maker of Both according to Panasonic Corporation

- Home Theater Geeks – 13: Plasma Geek Out (audio podcast)