Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

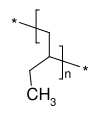

Polybutylene

View on Wikipedia | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

polybutene-1, poly(1-butene), PB-1

| |

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.111.056 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| (C4H8)n | |

| Density | 0.95 g/cm3[1] |

| Melting point | 135 °C (275 °F; 408 K)[1] |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds

|

1-butene (monomer) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Polybutylene (polybutene-1, poly(1-butene), PB-1) is a polyolefin or saturated polymer with the chemical formula (CH2CH(Et))n. Not be confused with polybutene, PB-1 is mainly used in piping.[2]

Production

[edit]Polybutylene is produced by polymerisation of 1-butene using supported Ziegler–Natta catalysts.

Catalysts

[edit]Isotactic PB-1 is produced commercially using two types of heterogeneous Ziegler–Natta catalysts.[3] The first type of catalyst contains two components, a solid pre-catalyst, the δ-crystalline form of TiCl3, and solution of an organoaluminum cocatalyst, such as Al(C2H5)3. The second type of pre-catalyst is supported. The active ingredient in the catalyst is TiCl4 and the support is microcrystalline MgCl2. These catalysts also contain special modifiers, organic compounds belonging to the classes of esters or ethers. The pre-catalysts are activated by combinations of organoaluminum compounds and other types of organic or organometallic modifiers. Two most important technological advantages of the supported catalysts are high productivity and a high fraction of the crystalline isotactic polymer they produce at 70–80 °C under standard polymerization conditions.[4][5][6]

Characteristics

[edit]PB-1 is a high molecular weight, linear, isotactic, and semi-crystalline polymer. PB-1 combines typical characteristics of conventional polyolefins with certain properties of technical polymers.

PB-1, when applied as a pure or reinforced resin, can replace materials like metal, rubber and engineering polymers. It is also used synergistically as a blend element to modify the characteristics of other polyolefins like polypropylene and polyethylene. Because of its specific properties it is mainly used in pressure piping, flexible packaging, water heaters, compounding and hot melt adhesives.

Heated up to 190 °C and above, PB-1 can easily be compression moulded, injection moulded, blown to hollow parts, extruded, and welded. It does not tend to crack due to stress.[dubious – discuss] Because of its crystalline structure and high molecular weight, PB-1 has good resistance to hydrostatic pressure, showing very low creep even at elevated temperatures.[7] It is flexible, resists impact well and has good elastic recovery.[3][8]

Isotactic polybutylene crystallizes in three different forms. Crystallization from solution yields form-III with the melting point of 106.5 °C. Cooling from the melt results in the form II which has melting point of 124 °C and density of 0.89 g/cm3. At room temperature, it spontaneously converts into the form-I with the melting point of 135 °C and density of 0.95 g/cm3.[1]

PB-1 generally resists chemicals such as detergents, oils, fats, acids, bases, alcohol, ketones, aliphatic hydrocarbons and hot polar solutions (including water).[3] It shows lower resistance to aromatic and chlorinated hydrocarbons as well as oxidising acids than other polymers such as polysulfone and polyamide 6/6.[7] Additional features include excellent wet abrasion resistance, easy melt flowability (shear thinning), and good dispersion of fillers. It is compatible with polypropylene, ethylene propylene rubbers, and thermoplastic elastomers.

Some properties:[7]

- Elastic modulus 290–295 MPa

- Tensile strength 36.5 MPa

- Molecular weight 725,000 (g/mol)

- Crystallinity 48–55%

- Water absorption <0.03%

- Glass transition temperature –25 to –17 °C [3][7]

- Thermal conductivity 0.22 W/(m·K)

Application areas

[edit]Piping systems

[edit]The main use of PB-1 is in flexible pressure piping systems for hot and cold drinking water distribution, pre-insulated district heating networks and surface heating and cooling systems. ISO 15876 defines the performance requirements of PB-1 piping systems.[9] PB-1's most notable characteristics are weldability, temperature resistance, flexibility and high hydrostatic pressure resistance. The material can be classified PB 125 with a minimum required strength (MRS) of 12.5 MPa. Other features include low noise transmission, low linear thermal expansion, no corrosion and calcification.

PB-1 piping systems are no longer being sold in North America (see "Class action lawsuits and removal from building code approved usage", below). The overall market share in Europe and Asia is rather small but PB-1 piping systems have shown a steady growth in recent years. In certain domestic markets, e.g. Kuwait, the United Kingdom, Korea and Spain, PB-1 piping systems have a strong position.[8]

Plastic packaging

[edit]Several PB-1 grades are commercially available for various applications and conversion technologies (blown film, cast film, extrusion coating). There are two main fields of application:

- Peelable easy-to-open packaging where PB-1 is used as blend component predominantly in polyethylene to tailor peel strength and peel quality, mainly in alimentary consumer packaging and medical packaging.

- Lowering seal initiation temperature (SIT) of high speed packaging polypropylene based films. Blending PB-1 into polypropylene, heat sealing temperatures as low as 65 °C can be achieved, maintaining a broad sealing window and good optical film properties.

Hot melt adhesives

[edit]PB-1 is compatible with a wide range of tackifier resins. It offers high cohesive and adhesive strength and helps tailoring the "open time" of the adhesive (up to 30 minutes) because of its slow crystallisation kinetics. It improves the thermal stability and the viscosity of the adhesive.[10]

Compounding and masterbatches

[edit]PB-1 accepts very high filler loadings in excess of 70%. In combination with its low melting point it can be employed in halogen-free flame retardant composites or as masterbatch carrier for thermo-sensitive pigments. PB-1 disperses easily in other polyolefins, and at low concentration, acts as processing aid reducing torque and/or increasing throughput.

Thermal insulation

[edit]PB-1 can be foamed.[11] The use of PB-1 foam as thermal insulation is of great advantage for district heating pipes, since the number of materials in the sandwich structure is reduced to one, facilitating its recycling.[12]

Other applications

[edit]Other applications include domestic water heaters, electrical insulation, compression packaging, wire and cable, shoe soles, and polyolefin modification (thermal bonding, enhancing softness and flexibility of rigid compounds, increasing temperature resistance and compression set of soft compounds).

Environmental longevity

[edit]Plumbing and heating systems made from PB-1 have been used in Europe and Asia for more than 30 years. First reference projects in district heating and floor heating systems in Germany and Austria from the early 1970s are still in operation today.[8]

One example is the installation of PB-1 pipes in the Vienna Geothermal Project (1974) where aggressive geothermal water is distributed at a service temperature of 54 °C and 10 bar pressure. Other pipe materials in the same installation failed or corroded and had been replaced in the meantime.[8]

International standards set minimum performance requirements for pipes made from PB-1 used in hot water applications. Standardized extrapolation methods predict lifetimes in excess of 50 years at 70 °C and 10 bar.[8]

Class action lawsuits and removal from building code approved usage

[edit]Polybutylene plumbing (marketed as Poly-B) was used in several million homes built in the United States and Canada from around 1978 to 1997. Problems with leaks and broken pipes led to a class action lawsuit, Cox v. Shell Oil, that was settled for $1 billion.[13][14] The leaks were associated with degradation of polybutylene exposed to chlorinated water.[15]

Polybutylene water pipes are no longer accepted by the United States building codes and have been the subject[16] of class action lawsuits in both Canada and the U.S.[17][18] The National Plumbing Code of Canada 1995 listed polybutylene piping as acceptable for use with the exception of recirculation plumbing. The piping was removed from the acceptable for use list in the 2005 issue of the standard.[19]

In Australia in March 2023, the Department of Mines, Industry Regulation and Safety reported that Australian homes built in 2019-2020 that had used a certain brand of polybutylene piping, had become the subject of an enquiry due to the significance of water leaks reported.[20][21]

There is evidence to suggest that the presence of chlorine and chloramine compounds in municipal water (often deliberately added to retard bacterial growth) will cause deterioration of the internal chemical structure of polybutylene piping and the associated acetal fittings.[22] The reaction with chlorinated water appears to be greatly accelerated by tensile stress, and is most often observed in material under highest mechanical stress such as at fittings, sharp bends, and kinks. Localized stress whitening of the material generally accompanies and precedes decomposition of the polymer. In extreme cases, this stress-activated chemical "corrosion" can lead to perforation and leakage within a few years, but it also may not fail for decades. Fittings with a soft compression seal can give adequate service life.[further explanation needed]

Because the chemical reaction of the water with the pipe occurs inside the pipe, it is often difficult to assess the extent of deterioration. The problem can cause both slow leaks and pipe bursting without any previous warning indication. The only long-term solution is to completely replace the polybutylene plumbing throughout the entire building.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Mark Alger, Mark S. M. Alger (1997). Polymer science dictionary. Springer. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-412-60870-4.

- ^ Whiteley, Kenneth S.; Heggs, T. Geoffrey; Koch, Hartmut; Mawer, Ralph L.; Immel, Wolfgang (2000). "Polyolefins". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_487. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ a b c d Charles A. Harper (2006). Handbook of plastics technologies: the complete guide to properties and performance. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-07-146068-2.

- ^ Hwo, Charles C.; Watkins, Larry K. Laminated film with improved tear strength, European Patent Application EP0459742, Publication date 12/04/1991

- ^ Boo-Deuk Kim et al. (2008) U.S. patent 7,442,489

- ^ Shimizu, Akihiko; Itakura, Keisuke; Otsu, Takayuki; Imoto, Minoru (1969). "Monomer-isomerization polymerization. VI. Isomerizations of butene-2 with TiCl3 or Al(C2H5)3–TiCl3 catalyst". Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 7 (11): 3119. Bibcode:1969JPoSA...7.3119S. doi:10.1002/pol.1969.150071108.

- ^ a b c d Freeman, Andrew; Mantell, Susan C.; Davidson, Jane H. (2005). "Mechanical performance of polysulfone, polybutylene, and polyamide 6/6 in hot chlorinated water". Solar Energy. 79 (6): 624–37. Bibcode:2005SoEn...79..624F. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2005.07.003.

- ^ a b c d e Polybutylene Archived November 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ISO 15876-1:2003 iso.org

- ^ T.E. Rolando (1998). Solvent-Free Adhesives. iSmithers Rapra. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-85957-133-0.

- ^ Doyle, Lucía (2022-03-20). "Extrusion foaming behavior of polybutene-1. Toward single-material multifunctional sandwich structures". Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 139 (12) 51816. doi:10.1002/app.51816. ISSN 0021-8995.

- ^ Doyle Gutierrez, Lucia (2022-12-02). A Circular Economy Approach to Multifunctional Sandwich Structures: Polymeric Foams for District Heating Pre-Insulated Pipes (Thesis thesis). HafenCity Universität Hamburg. doi:10.34712/142.35.

- ^ Hensler, Deborah R.; Pace, Nicholas M.; Dombey-Moore, Bonita; Giddens, Beth; Gross, Jennifer; Moller, Erik K. (2000). "Polybutylene Plumbing Pipes Litigation: Cox v. Shell Oil". In Hensler, Deborah R. (ed.). Class action dilemmas: pursuing public goals for private gain. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Institute for Civil Justice. pp. 375–98. ISBN 978-0-8330-2601-9.

- ^ Schneider, Martin (November 21, 1999). "Pipe problem getting fixed". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 2012-06-04. Retrieved 2010-07-29.

- ^ Vibien, P.; Couch, J.; Oliphant, K.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, B.; Chudnovsky, A. (2001). "Assessing material performance in chlorinated potable water applications" (PDF). Book Institute of Materials. 759: 863–72. ISSN 1366-5510. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-22. Retrieved 2010-07-30. also published as: Vibien, P.; Couch, J.; Oliphant, K.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, B.; Chudnovsky, A. (2001). "Chlorine resistance testing of cross-linked polyethylene piping materials". ANTEC 2001 Proceedings. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 2833–9. ISBN 978-1-58716-098-1.

- ^ Pipe dream is nightmare for many, Miami Herald - September 12, 1993

- ^ "DuPont USA Settlement of the Canadian Class Action Lawsuits". Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2010-10-01.

- ^ Polybutylene Plumbing Pipe Leak Relief

- ^ "Polybutylene (Poly-B) Pressure Water Piping" (PDF). municipalaffairs.alberta.ca. Government of Alberta. 2012-01-06. Retrieved 2019-09-09.

- ^ "Information for owners of new homes with polybutylene plumbing pipes" (PDF). commerce.wa.gov.au. March 21, 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2023. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ^ Batajtis, Damian (27 March 2023). "Comprehensive Guide to polybutylene Piping Issues and Solutions in Australia". Wizard Leak Detection. Archived from the original on 12 November 2023. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ^ Cause of failure in polybutylene pipe & acetal fittings http://www.polybutylene.com/poly.html

- ^ "Polybutylene Piping". PropEx.com. Archived from the original on 2015-08-29. Retrieved 2015-07-17.

Further reading

[edit]- Dunlop, Carson (2003). "Suspect Connections on Polybutylene Piping". Principles of Home Inspection: Plumbing. Chicago: Dearborn Home Inspection Education. pp. 84–7. ISBN 978-0-7931-7939-8.