Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Polyimide

View on Wikipedia

Polyimide (sometimes abbreviated PI) is a polymer containing imide groups belonging to the class of high-performance plastics. With their high heat-resistance, polyimides enjoy diverse applications in roles demanding rugged organic materials, such as high temperature fuel cells, displays, and various military roles. A classic polyimide is Kapton, which is produced by condensation of pyromellitic dianhydride and 4,4'-oxydianiline.[1]

History

[edit]The first polyimide was discovered in 1908 by Bogart and Renshaw.[2] They found that 4-amino phthalic anhydride does not melt when heated but does release water upon the formation of a high molecular weight polyimide. The first semialiphatic polyimide was prepared by Edward and Robinson by melt fusion of diamines and tetra acids or diamines and diacids/diester.[3]

However, the first polyimide of significant commercial importance—Kapton—was pioneered in the 1950s by workers at DuPont who developed a successful route for synthesis of high molecular weight polyimide involving a soluble polymer precursor. Up to today this route continues being the primary route for the production of most polyimides. Polyimides have been in mass production since 1955. The field of polyimides is covered by various extensive books[4][5] and review articles.[6][7]

Classification

[edit]According to the composition of their main chain, polyimides can be:

- Aliphatic,

- Semi-aromatic (also referred to as alipharomatic),

- Aromatic: these are the most used polyimides because of their thermostability.

According to the type of interactions between the main chains, polyimides can be:

- Thermoplastic: very often called pseudothermoplastic.

- Thermosetting: commercially available as uncured resins, polyimide solutions, stock shapes, thin sheets, laminates and machined parts.

Synthesis

[edit]Several methods are possible to prepare polyimides, among them:

- The reaction between a dianhydride and a diamine (the most used method).

- The reaction between a dianhydride and a diisocyanate.

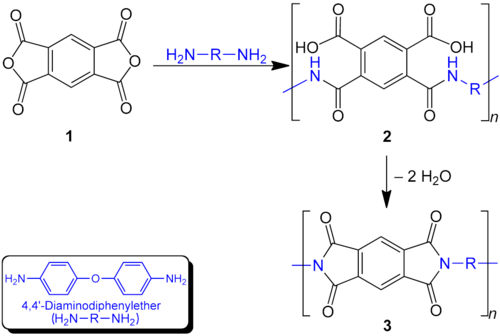

The polymerization of a diamine and a dianhydride can be carried out by a two-step method in which a poly(amidocarboxylic acid) is prepared first, or directly by a one-step method. The two-step method is the most widely used procedure for polyimide synthesis. First a soluble poly(amidocarboxylic acid) (2) is prepared which is cyclized after further processing in a second step to the polyimide (3). A two-step process is necessary because the final polyimides are in most cases infusible and insoluble due to their aromatic structure.

Dianhydrides used as precursors to these materials include pyromellitic dianhydride, benzoquinonetetracarboxylic dianhydride and naphthalene tetracarboxylic dianhydride. Common diamine building blocks include 4,4'-diaminodiphenyl ether (DAPE), meta-phenylenediamine (MDA) and 3,3'-diaminodiphenylmethane.[1] Hundreds of diamines and dianhydrides have been examined to tune the physical and especially the processing properties of these materials. These materials tend to be insoluble and have high softening temperatures, arising from charge-transfer interactions between the planar subunits.[8]

Analysis

[edit]The imidization reaction can be followed via IR spectroscopy. The IR spectrum is characterized during the reaction by the disappearance of absorption bands of the poly(amic acid) at 3400 to 2700 cm−1 (OH stretch), ~1720 and 1660 (amide C=O) and ~1535 cm−1 (C-N stretch). At the same time, the appearance of the characteristic imide bands can be observed, at ~1780 (C=O asymm), ~1720 (C=O symm), ~1360 (C-N stretch) and ~1160 and 745 cm−1 (imide ring deformation).[9] Detailed analyses of polyimide[10] and carbonized polyimide[10] and graphitized polyimide[11] have been reported.

Properties

[edit]Thermosetting polyimides are known for thermal stability, good chemical resistance, excellent mechanical properties, and characteristic orange/yellow color. Polyimides compounded with graphite or glass fiber reinforcements have flexural strengths of up to 340 MPa (49,000 psi) and flexural moduli of 21,000 MPa (3,000,000 psi). Thermoset polymer matrix polyimides exhibit very low creep and high tensile strength. These properties are maintained during continuous use to temperatures of up to 232 °C (450 °F) and for short excursions, as high as 704 °C (1,299 °F).[12] Molded polyimide parts and laminates have very good heat resistance. Normal operating temperatures for such parts and laminates range from cryogenic to those exceeding 260 °C (500 °F). Polyimides are also inherently resistant to flame combustion and do not usually need to be mixed with flame retardants. Most carry a UL rating of VTM-0. Polyimide laminates have a flexural strength half life at 249 °C (480 °F) of 400 hours.

Typical polyimide parts are not affected by commonly used solvents and oils – including hydrocarbons, esters, ethers, alcohols and freons. They also resist weak acids but are not recommended for use in environments that contain alkalis or inorganic acids. Some polyimides, such as CP1 and CORIN XLS, are solvent-soluble and exhibit high optical clarity. The solubility properties lend them towards spray and low temperature cure applications.

Applications

[edit]

Insulation and passivation films

[edit]Polyimide materials are lightweight, flexible, resistant to heat and chemicals. Therefore, they are used in the electronics industry for flexible cables and as an insulating film on magnet wire. For example, in a laptop computer, the cable that connects the main logic board to the display (which must flex every time the laptop is opened or closed) is often a polyimide base with copper conductors. Examples of polyimide films include Apical, Kapton, UPILEX, VTEC PI, Norton TH and Kaptrex.

Polyimide is used to coat optical fibers for medical or high temperature applications.[13]

An additional use of polyimide resin is as an insulating and passivation[14] layer in the manufacture of Integrated circuits and MEMS chips. The polyimide layers have good mechanical elongation and tensile strength, which also helps the adhesion between the polyimide layers or between polyimide layer and deposited metal layer. The minimum interaction between the gold film and the polyimide film, coupled with high temperature stability of the polyimide film, results in a system that provides reliable insulation when subjected to various types of environmental stresses.[15][16] Polyimide is also used as a substrate for cellphone antennas.[17]

Multi-layer insulation used on spacecraft is usually made of polyimide coated with thin layers of aluminum, silver, gold, or germanium. The gold-colored material often seen on the outside of spacecraft is typically actually single aluminized polyimide, with the single layer of aluminum facing in.[18] The yellowish-brown polyimide gives the surface its gold-like color.

Mechanical parts

[edit]Polyimide powder can be used to produce parts and shapes by sintering technologies (hot compression molding, direct forming, and isostatic pressing). Because of their high mechanical stability even at elevated temperatures they are used as bushings, bearings, sockets or constructive parts in demanding applications. To improve tribological properties, compounds with solid lubricants like graphite, PTFE, or molybdenum sulfide are common. Polyimide parts and shapes include P84 NT, VTEC PI, Meldin, Vespel, and Plavis.

Filters

[edit]In coal-fired power plants, waste incinerators, or cement plants, polyimide fibres are used to filter hot gases. In this application, a polyimide needle felt separates dust and particulate matter from the exhaust gas.

Polyimide is also the most common material used for the reverse osmotic film in purification of water, or the concentration of dilute materials from water, such as maple syrup production.[19][20]

Flexible circuits

[edit]Polyimide is used as the core of flexible circuit boards and flat-flex cables. Flexible circuit boards are thin and can be placed in odd-shaped electronics.[21]

Other

[edit]Polyimide is used for medical tubing, e.g. vascular catheters, for its burst pressure resistance combined with flexibility and chemical resistance.

The semiconductor industry uses polyimide as a high-temperature adhesive; it is also used as a mechanical stress buffer.

Some polyimide can be used like a photoresist; both "positive" and "negative" types of photoresist-like polyimide exist in the market.

The IKAROS solar sailing spacecraft uses polyimide resin sails to operate without rocket engines.[22]

See also

[edit]- Polyimine – Type of polymer material

- Polyamide – Macromolecule with repeating units linked by amide bonds

- Polyamide-imide – Class of polymers

- Polymerization – Chemical reaction to form polymer chains

References

[edit]- ^ a b Wright, Walter W. and Hallden-Abberton, Michael (2002) "Polyimides" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_253

- ^ Bogert, Marston Taylor; Renshaw, Roemer Rex (1 July 1908). "4-Amino-0-Phthalic Acid and Some of ITS Derivatives.1". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 30 (7): 1135–1144. doi:10.1021/ja01949a012. hdl:2027/mdp.39015067267875. ISSN 0002-7863.

- ^ US 2710853, Edwards, W. M.; Robinson, I. M., "Polyimides of pyromellitic acid"

- ^ Polyimides : fundamentals and applications. Ghosh, Malay K., Mittal, K. L., 1945-. New York: Marcel Dekker. 1996. ISBN 0-8247-9466-4. OCLC 34745932.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Wilson, D. (Doug), Stenzenberger, H. D. (Horst D.), Hergenrother, P. M. (Paul M.) (1990). Polyimides. Glasgow: Blackie. ISBN 0-412-02181-1. OCLC 19886566.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sroog, C.E. (August 1991). "Polyimides". Progress in Polymer Science. 16 (4): 561–694. doi:10.1016/0079-6700(91)90010-I.

- ^ Hergenrother, Paul M. (27 July 2016). "The Use, Design, Synthesis, and Properties of High Performance/High Temperature Polymers: An Overview". High Performance Polymers. 15: 3–45. doi:10.1177/095400830301500101. S2CID 93989040.

- ^ Liaw, Der-Jang; Wang, Kung-Li; Huang, Ying-Chi; Lee, Kueir-Rarn; Lai, Juin-Yih; Ha, Chang-Sik (2012). "Advanced polyimide materials: Syntheses, physical properties and applications". Progress in Polymer Science. 37 (7): 907–974. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2012.02.005.

- ^ K. Faghihi, J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2006, 102, 5062–5071. Y. Kung and S. Hsiao, J. Mater. Chem., 2011, 1746–1754. L. Burakowski, M. Leali and M. Angelo, Mater. Res., 2010, 13, 245–252.

- ^ a b Kato, Tomofumi; Yamada, Yasuhiro; Nishikawa, Yasushi; Ishikawa, Hiroki; Sato, Satoshi (30 June 2021). "Carbonization mechanisms of polyimide: Methodology to analyze carbon materials with nitrogen, oxygen, pentagons, and heptagons". Carbon. 178: 58–80. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2021.02.090. ISSN 0008-6223. S2CID 233539984.

- ^ Kato, Tomofumi; Yamada, Yasuhiro; Nishikawa, Yasushi; Otomo, Toshiya; Sato, Hayato; Sato, Satoshi (1 October 2021). "Origins of peaks of graphitic and pyrrolic nitrogen in N1s X-ray photoelectron spectra of carbon materials: quaternary nitrogen, tertiary amine, or secondary amine?". Journal of Materials Science. 56 (28): 15798–15811. Bibcode:2021JMatS..5615798K. doi:10.1007/s10853-021-06283-5. ISSN 1573-4803. S2CID 235793266.

- ^ P2SI 900HT Tech Sheet. proofresearchacd.com

- ^ Huang, Lei; Dyer, Robert S.; Lago, Ralph J.; Stolov, Andrei A.; Li, Jie (2016). "Mechanical properties of polyimide coated optical fibers at elevated temperatures". In Gannot, Israel (ed.). Optical Fibers and Sensors for Medical Diagnostics and Treatment Applications XVI. Vol. 9702. pp. 97020Y. doi:10.1117/12.2210957. S2CID 123400822.

- ^ Jiang, Jiann-Shan; Chiou, Bi-Shiou (2001). "The effect of polyimide passivation on the electromigration of Cu multilayer interconnections". Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics. 12 (11): 655–659. doi:10.1023/A:1012802117916. S2CID 136747058.

- ^ Krakauer, David (December 2006) Digital Isolation Offers Compact, Low-Cost Solutions to Challenging Design Problems. analog.com

- ^ Chen, Baoxing. iCoupler Products with isoPower Technology: Signal and Power Transfer Across Isolation Barrier Using Microtransformers. analog.com

- ^ "Apple to adopt speedy LCP circuit board tech across major product lines in 2018".

- ^ "Thermal Control Overview" (PDF). Sheldahl Multi Layer Insulation. Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ What is a reverse osmosis water softener? wisegeek.net

- ^ Shuey, Harry F. and Wan, Wankei (22 December 1983) U.S. patent 4,532,041 Asymmetric polyimide reverse osmosis membrane, method for preparation of same and use thereof for organic liquid separations.

- ^ MCL (13 June 2017). "What is the Difference between FR4 and Polyamide PCB". mcl. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ Courtland, Rachel (10 May 2010). "Maiden voyage for first true space sail". The New Scientist. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Modern Plastic Mid-October Encyclopedia Issue, Polyimide, thermoset, p. 146.

- Varun Ratta: POLYIMIDES: Chemistry & structure-property relationships – literature review (Chapter 1).