Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

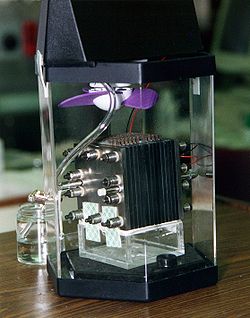

Fuel cell

View on WikipediaThis article needs to be updated. (February 2021) |

A fuel cell is an electrochemical cell that converts the chemical energy of a fuel (often hydrogen) and an oxidizing agent (often oxygen)[1] into electricity through a pair of redox reactions.[2] Fuel cells are different from most batteries in requiring a continuous source of fuel and oxygen (usually from air) to sustain the chemical reaction, whereas in a battery the chemical energy usually comes from substances that are already present in the battery.[3] Fuel cells can produce electricity continuously for as long as fuel and oxygen are supplied.

The first fuel cells were invented by Sir William Grove in 1838. The first commercial use of fuel cells came almost a century later following the invention of the hydrogen–oxygen fuel cell by Francis Thomas Bacon in 1932. The alkaline fuel cell, also known as the Bacon fuel cell after its inventor, has been used in NASA space programs since the mid-1960s to generate power for satellites and space capsules. Since then, fuel cells have been used in many other applications. Fuel cells are used for primary and backup power for commercial, industrial and residential buildings and in remote or inaccessible areas. They are also used to power fuel cell vehicles, including forklifts, automobiles, buses,[4] trains, boats, motorcycles, and submarines.

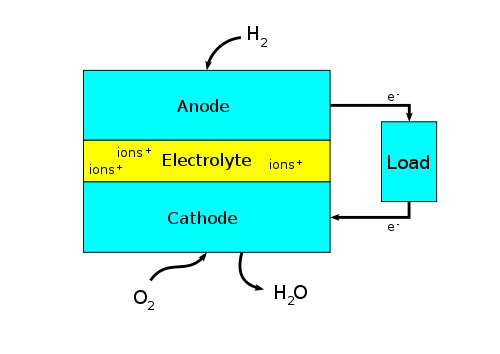

There are many types of fuel cells, but they all consist of an anode, a cathode, and an electrolyte that allows ions, often positively charged hydrogen ions (protons), to move between the two sides of the fuel cell. At the anode, a catalyst causes the fuel to undergo oxidation reactions that generate ions (often positively charged hydrogen ions) and electrons. The ions move from the anode to the cathode through the electrolyte. At the same time, electrons flow from the anode to the cathode through an external circuit, producing direct current electricity. At the cathode, another catalyst causes ions, electrons, and oxygen to react, forming water and possibly other products. Fuel cells are classified by the type of electrolyte they use and by the difference in start-up time ranging from 1 second for proton-exchange membrane fuel cells (PEM fuel cells, or PEMFC) to 10 minutes for solid oxide fuel cells (SOFC). A related technology is flow batteries, in which the fuel can be regenerated by recharging. Individual fuel cells produce relatively small electrical potentials, about 0.7 volts, so cells are "stacked", or placed in series, to create sufficient voltage to meet an application's requirements.[5] In addition to electricity, fuel cells produce water vapor, heat and, depending on the fuel source, very small amounts of nitrogen dioxide and other emissions. PEMFC cells generally produce fewer nitrogen oxides than SOFC cells: they operate at lower temperatures, use hydrogen as fuel, and limit the diffusion of nitrogen into the anode via the proton exchange membrane, which forms NOx. The energy efficiency of a fuel cell is generally between 40 and 60%; however, if waste heat is captured in a cogeneration scheme, efficiencies of up to 85% can be obtained.[6]

History

[edit]

The first references to hydrogen fuel cells appeared in 1838. In a letter dated October 1838 but published in the December 1838 edition of The London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, Welsh physicist and barrister Sir William Grove wrote about the development of his first crude fuel cells. He used a combination of sheet iron, copper, and porcelain plates, and a solution of sulphate of copper and dilute acid.[7][8] In a letter to the same publication written in December 1838 but published in June 1839, German physicist Christian Friedrich Schönbein discussed the first crude fuel cell that he had invented. His letter discussed the current generated from hydrogen and oxygen dissolved in water.[9] Grove later sketched his design, in 1842, in the same journal. The fuel cell he made used similar materials to today's phosphoric acid fuel cell.[10][11]

In 1932, English engineer Francis Thomas Bacon successfully developed a 5 kW stationary fuel cell.[12] NASA used the alkaline fuel cell (AFC), also known as the Bacon fuel cell after its inventor, from the mid-1960s.[12][13]

In 1955, W. Thomas Grubb, a chemist working for the General Electric Company (GE), further modified the original fuel cell design by using a sulphonated polystyrene ion-exchange membrane as the electrolyte. Three years later another GE chemist, Leonard Niedrach, devised a way of depositing platinum onto the membrane, which served as a catalyst for the necessary hydrogen oxidation and oxygen reduction reactions. This became known as the "Grubb-Niedrach fuel cell".[14][15] GE went on to develop this technology with NASA and McDonnell Aircraft, leading to its use during Project Gemini. This was the first commercial use of a fuel cell. In 1959, a team led by Harry Ihrig built a 15 kW fuel cell tractor for Allis-Chalmers, which was demonstrated across the U.S. at state fairs. This system used potassium hydroxide as the electrolyte and compressed hydrogen and oxygen as the reactants. Later in 1959, Bacon and his colleagues demonstrated a practical five-kilowatt unit capable of powering a welding machine. In the 1960s, Pratt & Whitney licensed Bacon's U.S. patents for use in the U.S. space program to supply electricity and drinking water (hydrogen and oxygen being readily available from the spacecraft tanks).

UTC Power was the first company to manufacture and commercialize a large, stationary fuel cell system for use as a cogeneration power plant in hospitals, universities and large office buildings.[16]

In recognition of the fuel cell industry and America's role in fuel cell development, the United States Senate recognized October 8, 2015 as National Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Day, passing S. RES 217. The date was chosen in recognition of the atomic weight of hydrogen (1.008).[17]

Types of fuel cells; design

[edit]Fuel cells come in many varieties; however, they all work in the same general manner. They are made up of three adjacent segments: the anode, the electrolyte, and the cathode. Two chemical reactions occur at the interfaces of the three different segments. The net result of the two reactions is that fuel is consumed, water or carbon dioxide is created, and an electric current is created, which can be used to power electrical devices, normally referred to as the load.

At the anode a catalyst ionizes the fuel, turning the fuel into a positively charged ion and a negatively charged electron. The electrolyte is a substance specifically designed so ions can pass through it, but the electrons cannot. The freed electrons travel through a wire creating an electric current. The ions travel through the electrolyte to the cathode. Once reaching the cathode, the ions are reunited with the electrons and the two react with a third chemical, usually oxygen, to create water or carbon dioxide.

Design features in a fuel cell include:

- The electrolyte substance, which usually defines the type of fuel cell, and can be made from a number of substances like potassium hydroxide, salt carbonates, and phosphoric acid.[18]

- The most common fuel that is used is hydrogen.

- The anode catalyst, usually fine platinum powder, breaks down the fuel into electrons and ions.

- The cathode catalyst, often nickel, converts ions into waste chemicals, with water being the most common type of waste.[19]

- Gas diffusion layers that are designed to resist oxidization.[19]

A typical fuel cell produces a voltage from 0.6 to 0.7 V at a full-rated load. Voltage decreases as current increases, due to several factors:

- Activation loss

- Ohmic loss (voltage drop due to resistance of the cell components and interconnections)

- Mass transport loss (depletion of reactants at catalyst sites under high loads, causing rapid loss of voltage).[20]

To deliver the desired amount of energy, the fuel cells can be combined in series to yield higher voltage, and in parallel to allow a higher current to be supplied. Such a design is called a fuel cell stack. The cell surface area can also be increased, to allow higher current from each cell.

Proton-exchange membrane fuel cells

[edit]

In the archetypical hydrogen–oxide proton-exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) design, a proton-conducting polymer membrane (typically nafion) contains the electrolyte solution that separates the anode and cathode sides.[24][25] This was called a solid polymer electrolyte fuel cell (SPEFC) in the early 1970s, before the proton-exchange mechanism was well understood. (Notice that the synonyms polymer electrolyte membrane and proton-exchange mechanism result in the same acronym.)

On the anode side, hydrogen diffuses to the anode catalyst where it later dissociates into protons and electrons. These protons often react with oxidants causing them to become what are commonly referred to as multi-facilitated proton membranes. The protons are conducted through the membrane to the cathode, but the electrons are forced to travel in an external circuit (supplying power) because the membrane is electrically insulating. On the cathode catalyst, oxygen molecules react with the electrons (which have traveled through the external circuit) and protons to form water.

In addition to this pure hydrogen type, there are hydrocarbon fuels for fuel cells, including diesel, methanol (see: direct-methanol fuel cells and indirect methanol fuel cells) and chemical hydrides. The waste products with these types of fuel are carbon dioxide and water. When hydrogen is used, the CO2 is released when methane from natural gas is combined with steam, in a process called steam methane reforming, to produce the hydrogen. This can take place in a different location to the fuel cell, potentially allowing the hydrogen fuel cell to be used indoors—for example, in forklifts.

The different components of a PEMFC are

- bipolar plates,

- electrodes,

- catalyst,

- membrane, and

- the necessary hardware such as current collectors and gaskets.[26]

The materials used for different parts of the fuel cells differ by type. The bipolar plates may be made of different types of materials, such as, metal, coated metal, graphite, flexible graphite, C–C composite, carbon–polymer composites etc.[27] The membrane electrode assembly (MEA) is referred to as the heart of the PEMFC and is usually made of a proton-exchange membrane sandwiched between two catalyst-coated carbon papers. Platinum and/or similar types of noble metals are usually used as the catalyst for PEMFC, and these can be contaminated by carbon monoxide, necessitating a relatively pure hydrogen fuel.[28] The electrolyte could be a polymer membrane.

Proton-exchange membrane fuel cell design issues

[edit]- Cost

- In 2013, the Department of Energy estimated that 80 kW automotive fuel cell system costs of US$67 per kilowatt could be achieved, assuming volume production of 100,000 automotive units per year and US$55 per kilowatt could be achieved, assuming volume production of 500,000 units per year.[29] Many companies are working on techniques to reduce cost in a variety of ways including reducing the amount of platinum needed in each individual cell. Ballard Power Systems has experimented with a catalyst enhanced with carbon silk, which allows a 30% reduction (1.0–0.7 mg/cm2) in platinum usage without reduction in performance.[30] Monash University, Melbourne uses PEDOT as a cathode.[31] A 2011-published study[32] documented the first metal-free electrocatalyst using relatively inexpensive doped carbon nanotubes, which are less than 1% the cost of platinum and are of equal or superior performance. A recently published article demonstrated how the environmental burdens change when using carbon nanotubes as carbon substrate for platinum.[33]

- Water and air management[34][35] (in PEMFCs)

- In this type of fuel cell, the membrane must be hydrated, requiring water to be evaporated at precisely the same rate that it is produced. If water is evaporated too quickly, the membrane dries, the resistance across it increases, and eventually, it will crack, creating a gas "short circuit" where hydrogen and oxygen combine directly, generating heat that will damage the fuel cell. If the water is evaporated too slowly, the electrodes will flood, preventing the reactants from reaching the catalyst and stopping the reaction. Methods to manage water in cells are being developed like electroosmotic pumps focusing on flow control. Just as in a combustion engine, a steady ratio between the reactant and oxygen is necessary to keep the fuel cell operating efficiently.

- Temperature management

- The same temperature must be maintained throughout the cell in order to prevent destruction of the cell through thermal loading. This is particularly challenging as the 2H2 + O2 → 2H2O reaction is highly exothermic, so a large quantity of heat is generated within the fuel cell.

- Durability, service life, and special requirements for some type of cells

- Stationary fuel-cell applications typically require more than 40,000 hours of reliable operation at a temperature of −35 to 40 °C (−31 to 104 °F), while automotive fuel cells require a 5,000-hour lifespan (the equivalent of 240,000 km or 150,000 miles) under extreme temperatures. Current service life is 2,500 hours (about 120,000 km or 75,000 mi).[36] Automotive engines must also be able to start reliably at −30 °C (−22 °F) and have a high power-to-volume ratio (typically 2.5 kW/L).

- Limited carbon monoxide tolerance of some (non-PEDOT) cathodes.[28]

Phosphoric acid fuel cell

[edit]Phosphoric acid fuel cells (PAFCs) were first designed and introduced in 1961 by G. V. Elmore and H. A. Tanner. In these cells, phosphoric acid is used as a non-conductive electrolyte to pass protons from the anode to the cathode and to force electrons to travel from anode to cathode through an external electrical circuit. These cells commonly work in temperatures of 150 to 200 °C. This high temperature will cause heat and energy loss if the heat is not removed and used properly. This heat can be used to produce steam for air conditioning systems or any other thermal energy-consuming system.[37] Using this heat in cogeneration can enhance the efficiency of phosphoric acid fuel cells from 40 to 50% to about 80%.[37] Since the proton production rate on the anode is small, platinum is used as a catalyst to increase this ionization rate. A key disadvantage of these cells is the use of an acidic electrolyte. This increases the corrosion or oxidation of components exposed to phosphoric acid.[38]

Solid acid fuel cell

[edit]Solid acid fuel cells (SAFCs) are characterized by the use of a solid acid material as the electrolyte. At low temperatures, solid acids have an ordered molecular structure like most salts. At warmer temperatures (between 140 and 150 °C for CsHSO4), some solid acids undergo a phase transition to become highly disordered "superprotonic" structures, which increases conductivity by several orders of magnitude. SAFC systems use cesium dihydrogen phosphate (CsH2PO4) and have demonstrated lifetimes in the thousands of hours.[39]

Alkaline fuel cell

[edit]The alkaline fuel cell (AFC) or hydrogen-oxygen fuel cell was designed and first demonstrated publicly by Francis Thomas Bacon in 1959. It was used as a primary source of electrical energy in the Apollo space program.[40] The cell consists of two porous carbon electrodes impregnated with a suitable catalyst such as Pt, Ag, CoO, etc. The space between the two electrodes is filled with a concentrated solution of KOH or NaOH which serves as an electrolyte. H2 gas and O2 gas are bubbled into the electrolyte through the porous carbon electrodes. Thus the overall reaction involves the combination of hydrogen gas and oxygen gas to form water. The cell runs continuously until the reactant's supply is exhausted. This type of cell operates efficiently in the temperature range 343–413 K (70 -140 °C) and provides a potential of about 0.9 V.[41] Alkaline anion exchange membrane fuel cell (AAEMFC) is a type of AFC which employs a solid polymer electrolyte instead of aqueous potassium hydroxide (KOH) and it is superior to aqueous AFC.

High-temperature fuel cells

[edit]Solid oxide fuel cell

[edit]Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) use a solid material, most commonly a ceramic material called yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ), as the electrolyte. Because SOFCs are made entirely of solid materials, they are not limited to the flat plane configuration of other types of fuel cells and are often designed as rolled tubes. They require high operating temperatures (800–1000 °C) and can be run on a variety of fuels including natural gas.[6]

SOFCs are unique because negatively charged oxygen ions travel from the cathode (positive side of the fuel cell) to the anode (negative side of the fuel cell) instead of protons travelling vice versa (i.e., from the anode to the cathode), as is the case in all other types of fuel cells. Oxygen gas is fed through the cathode, where it absorbs electrons to create oxygen ions. The oxygen ions then travel through the electrolyte to react with hydrogen gas at the anode. The reaction at the anode produces electricity and water as by-products. Carbon dioxide may also be a by-product depending on the fuel, but the carbon emissions from a SOFC system are less than those from a fossil fuel combustion plant.[42] The chemical reactions for the SOFC system can be expressed as follows:[43]

- Anode reaction: 2H2 + 2O2− → 2H2O + 4e−

- Cathode reaction: O2 + 4e− → 2O2−

- Overall cell reaction: 2H2 + O2 → 2H2O

SOFC systems can run on fuels other than pure hydrogen gas. However, since hydrogen is necessary for the reactions listed above, the fuel selected must contain hydrogen atoms. For the fuel cell to operate, the fuel must be converted into pure hydrogen gas. SOFCs are capable of internally reforming light hydrocarbons such as methane (natural gas),[44] propane, and butane.[45] These fuel cells are at an early stage of development.[46]

Challenges exist in SOFC systems due to their high operating temperatures. One such challenge is the potential for carbon dust to build up on the anode, which slows down the internal reforming process. Research to address this "carbon coking" issue at the University of Pennsylvania has shown that the use of copper-based cermet (heat-resistant materials made of ceramic and metal) can reduce coking and the loss of performance.[47] Another disadvantage of SOFC systems is the long start-up, making SOFCs less useful for mobile applications. Despite these disadvantages, a high operating temperature provides an advantage by removing the need for a precious metal catalyst like platinum, thereby reducing cost. Additionally, waste heat from SOFC systems may be captured and reused, increasing the theoretical overall efficiency to as high as 80–85%.[6]

The high operating temperature is largely due to the physical properties of the YSZ electrolyte. As temperature decreases, so does the ionic conductivity of YSZ. Therefore, to obtain the optimum performance of the fuel cell, a high operating temperature is required. According to their website, Ceres Power, a UK SOFC fuel cell manufacturer, has developed a method of reducing the operating temperature of their SOFC system to 500–600 degrees Celsius. They replaced the commonly used YSZ electrolyte with a CGO (cerium gadolinium oxide) electrolyte. The lower operating temperature allows them to use stainless steel instead of ceramic as the cell substrate, which reduces cost and start-up time of the system.[48]

Molten-carbonate fuel cell

[edit]Molten carbonate fuel cells (MCFCs) require a high operating temperature, 650 °C (1,200 °F), similar to SOFCs. MCFCs use lithium potassium carbonate salt as an electrolyte, and this salt liquefies at high temperatures, allowing for the movement of charge within the cell – in this case, negative carbonate ions.[49]

Like SOFCs, MCFCs are capable of converting fossil fuel to a hydrogen-rich gas in the anode, eliminating the need to produce hydrogen externally. The reforming process creates CO2 emissions. MCFC-compatible fuels include natural gas, biogas and gas produced from coal. The hydrogen in the gas reacts with carbonate ions from the electrolyte to produce water, carbon dioxide, electrons and small amounts of other chemicals. The electrons travel through an external circuit, creating electricity, and return to the cathode. There, oxygen from the air and carbon dioxide recycled from the anode react with the electrons to form carbonate ions that replenish the electrolyte, completing the circuit.[49] The chemical reactions for an MCFC system can be expressed as follows:[50]

- Anode reaction: CO32− + H2 → H2O + CO2 + 2e−

- Cathode reaction: CO2 + ½O2 + 2e− → CO32−

- Overall cell reaction: H2 + ½O2 → H2O

As with SOFCs, MCFC disadvantages include slow start-up times because of their high operating temperature. This makes MCFC systems not suitable for mobile applications, and this technology will most likely be used for stationary fuel-cell purposes. The main challenge of MCFC technology is the cells' short life span. The high-temperature and carbonate electrolyte lead to corrosion of the anode and cathode. These factors accelerate the degradation of MCFC components, decreasing the durability and cell life. Researchers are addressing this problem by exploring corrosion-resistant materials for components as well as fuel cell designs that may increase cell life without decreasing performance.[6]

MCFCs hold several advantages over other fuel cell technologies, including their resistance to impurities. They are not prone to "carbon coking", which refers to carbon build-up on the anode that results in reduced performance by slowing down the internal fuel reforming process. Therefore, carbon-rich fuels like gases made from coal are compatible with the system. The United States Department of Energy claims that coal, itself, might even be a fuel option in the future, assuming the system can be made resistant to impurities such as sulfur and particulates that result from converting coal into hydrogen.[6] MCFCs also have relatively high efficiencies. They can reach a fuel-to-electricity efficiency of 50%, considerably higher than the 37–42% efficiency of a phosphoric acid fuel cell plant. Efficiencies can be as high as 65% when the fuel cell is paired with a turbine, and 85% if heat is captured and used in a combined heat and power (CHP) system.[49]

FuelCell Energy, a Connecticut-based fuel cell manufacturer, develops and sells MCFC fuel cells. The company says that their MCFC products range from 300 kW to 2.8 MW systems that achieve 47% electrical efficiency and can utilize CHP technology to obtain higher overall efficiencies. One product, the DFC-ERG, is combined with a gas turbine and, according to the company, it achieves an electrical efficiency of 65%.[51]

Electric storage fuel cell

[edit]The electric storage fuel cell is a conventional battery chargeable by electric power input, using the conventional electro-chemical effect. However, the battery further includes hydrogen (and oxygen) inputs for alternatively charging the battery chemically.[52]

Biofuel cell

[edit]A biofuel cell converts chemical energy from biological substances into electrical energy using biological catalysts, such as enzymes or microorganisms. The process involves the oxidation of a fuel, like glucose, at the anode, releasing electrons and protons. The electrons travel through an external circuit to generate electrical current, while at the cathode, oxygen is typically reduced to water or hydrogen peroxide, completing the circuit.[53] Applications include wastewater treatment and renewable energy production.[54] Conductive polymers may be used to improve electron transfer between enzymes and electrodes. [55]

The integration of nanomaterials, such as carbon nanotubes and metal nanoparticles, are used to enhance the performance of BFCs. These materials increase the surface area of electrodes and facilitate better electron transfer, resulting in higher power densities. Three-dimensional porous structures and graphene-based materials, have been used to improve conductivity and stability, and hybrid biofuel cells that combine BFCs with supercapacitors or secondary batteries are being developed to provide stable and continuous energy output.[56] BFCs are being explored as power sources for implantable devices like pacemakers and biosensors.to potentially eliminate the need for traditional batteries, and fiber-type EBFCs show potential in implantable applications.[57] The power density of BFCs, however, is generally lower than that of conventional energy sources, the stability of enzymes and microorganisms over extended periods is another concern, and scalability and commercial viability also pose hurdles.[58]

Comparison of fuel cell types

[edit]| Fuel cell name | Electrolyte | Qualified power (W) | Working temperature (°C) | Efficiency | Status | Cost (USD/W) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell | System | ||||||

| Electro-galvanic fuel cell | Aqueous alkaline solution | < 40 | Commercial / Research | 3-7 | |||

| Direct formic acid fuel cell (DFAFC) | Polymer membrane (ionomer) | < 50 W | < 40 | Commercial / Research | 10-20 | ||

| Alkaline fuel cell | Aqueous alkaline solution | 10–200 kW | < 80 | 60–70% | 62% | Commercial / Research | 50-100 |

| Proton-exchange membrane fuel cell | Polymer membrane (ionomer) | 1 W – 500 kW | 50–100 (Nafion)[59] 120–200 (PBI)[60] |

50–70% | 30–50%[61] | Commercial / Research | 50–100 |

| Metal hydride fuel cell | Aqueous alkaline solution | > −20 (50% Ppeak @ 0 °C) |

Commercial / Research | 30-200 | |||

| Zinc–air battery | Aqueous alkaline solution | < 40 | Mass production | 150-300 | |||

| Direct carbon fuel cell | Several different | 700–850 | 80% | 70% | Commercial / Research | 18 | |

| Direct borohydride fuel cell | Aqueous alkaline solution | 70 | Commercial | 400-450 | |||

| Microbial fuel cell | Polymer membrane or humic acid | < 40 | Research | 10-50 | |||

| Upflow microbial fuel cell (UMFC) | < 40 | Research | 1-5 | ||||

| Regenerative fuel cell | Polymer membrane (ionomer) | < 50 | Commercial / Research | 200-300 | |||

| Direct methanol fuel cell | Polymer membrane (ionomer) | 100 mW – 1 kW | 90–120 | 20–30% | 10–25%[61] | Commercial / Research | 125 |

| Reformed methanol fuel cell | Polymer membrane (ionomer) | 5 W – 100 kW | 250–300 (reformer) 125–200 (PBI) |

50–60% | 25–40% | Commercial / Research | 8.50 |

| Direct-ethanol fuel cell | Polymer membrane (ionomer) | < 140 mW/cm² | > 25 ? 90–120 |

Research | 12 | ||

| Redox fuel cell[broken anchor] (RFC) | Liquid electrolytes with redox shuttle and polymer membrane (ionomer) | 1 kW – 10 MW | Research | 12.50 | |||

| Phosphoric acid fuel cell | Molten phosphoric acid (H3PO4) | < 10 MW | 150–200 | 55% | 40%[61] Co-gen: 90% |

Commercial / Research | 4.00–4.50 |

| Solid acid fuel cell | H+-conducting oxyanion salt (solid acid) | 10 W – 1 kW | 200–300 | 55–60% | 40–45% | Commercial / Research | 15 |

| Molten carbonate fuel cell | Molten alkaline carbonate | 100 MW | 600–650 | 55% | 45–55%[61] | Commercial / Research | 1000 |

| Tubular solid oxide fuel cell (TSOFC) | O2−-conducting ceramic oxide | < 100 MW | 850–1100 | 60–65% | 55–60% | Commercial / Research | 3.50 |

| Protonic ceramic fuel cell | H+-conducting ceramic oxide | 700 | Research | 80 | |||

| Planar solid oxide fuel cell | O2−-conducting ceramic oxide | < 100 MW | 500–1100 | 60–65% | 55–60%[61] | Commercial / Research | 800 |

| Enzymatic biofuel cells | Any that will not denature the enzyme | < 40 | Research | 10 | |||

| Magnesium-air fuel cell | Salt water | −20 to 55 | 90% | Commercial / Research | 15 | ||

Glossary of terms in table:

- Anode

- The electrode at which oxidation (a loss of electrons) takes place. For fuel cells and other galvanic cells, the anode is the negative terminal; for electrolytic cells (where electrolysis occurs), the anode is the positive terminal.[62]

- Aqueous solution[63]

- Of, relating to, or resembling water

- Made from, with, or by water.

- Catalyst

- A chemical substance that increases the rate of a reaction without being consumed; after the reaction, it can potentially be recovered from the reaction mixture and is chemically unchanged. The catalyst lowers the activation energy required, allowing the reaction to proceed more quickly or at a lower temperature. In a fuel cell, the catalyst facilitates the reaction of oxygen and hydrogen. It is usually made of platinum powder very thinly coated onto carbon paper or cloth. The catalyst is rough and porous so the maximum surface area of the platinum can be exposed to the hydrogen or oxygen. The platinum-coated side of the catalyst faces the membrane in the fuel cell.[62]

- Cathode

- The electrode at which reduction (a gain of electrons) occurs. For fuel cells and other galvanic cells, the cathode is the positive terminal; for electrolytic cells (where electrolysis occurs), the cathode is the negative terminal.[62]

- Electrolyte

- A substance that conducts charged ions from one electrode to the other in a fuel cell, battery, or electrolyzer.[62]

- Fuel cell stack

- Individual fuel cells connected in a series. Fuel cells are stacked to increase voltage.[62]

- Matrix

- something within or from which something else originates, develops, or takes form.[64]

- Membrane

- The separating layer in a fuel cell that acts as electrolyte (an ion-exchanger) as well as a barrier film separating the gases in the anode and cathode compartments of the fuel cell.[62]

- Molten carbonate fuel cell (MCFC)

- A type of fuel cell that contains a molten carbonate electrolyte. Carbonate ions (CO32−) are transported from the cathode to the anode. Operating temperatures are typically near 650 °C.[62]

- Phosphoric acid fuel cell (PAFC)

- A type of fuel cell in which the electrolyte consists of concentrated phosphoric acid (H3PO4). Protons (H+) are transported from the anode to the cathode. The operating temperature range is generally 160–220 °C.[62]

- Proton-exchange membrane fuel cell (PEM)

- A fuel cell incorporating a solid polymer membrane used as its electrolyte. Protons (H+) are transported from the anode to the cathode. The operating temperature range is generally 60–100 °C for Low Temperature Proton-exchange membrane fuel cell (LT-PEMFC).[62] PEM fuel cell with operating temperature of 120-200 °C is called High Temperature Proton-exchange membrane fuel cell (HT-PEMFC).[65]

- Solid oxide fuel cell (SOFC)

- A type of fuel cell in which the electrolyte is a solid, nonporous metal oxide, typically zirconium oxide (ZrO2) treated with Y2O3, and O2− is transported from the cathode to the anode. Any CO in the reformate gas is oxidized to CO2 at the anode. Temperatures of operation are typically 800–1,000 °C.[62]

- Solution[66]

- An act or the process by which a solid, liquid, or gaseous substance is homogeneously mixed with a liquid or sometimes a gas or solid.

- A homogeneous mixture formed by this process; especially : a single-phase liquid system.

- The condition of being dissolved.

Efficiency of leading fuel cell types

[edit]Theoretical maximum efficiency

[edit]The energy efficiency of a system or device that converts energy is measured by the ratio of the amount of useful energy put out by the system ("output energy") to the total amount of energy that is put in ("input energy") or by useful output energy as a percentage of the total input energy. In the case of fuel cells, useful output energy is measured in electrical energy produced by the system. Input energy is the energy stored in the fuel. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, fuel cells are generally between 40 and 60% energy efficient.[67] This is higher than some other systems for energy generation. For example, the internal combustion engine of a car can be about 43% energy efficient.[68][69] Steam power plants usually achieve efficiencies of 30-40%[70] while combined cycle gas turbine and steam plants can achieve efficiencies above 60%.[71][72] In combined heat and power (CHP) systems, the waste heat produced by the primary power cycle - whether fuel cell, nuclear fission or combustion - is captured and put to use, increasing the efficiency of the system to up to 85–90%.[6]

The theoretical maximum efficiency of any type of power generation system is never reached in practice, and it does not consider other steps in power generation, such as production, transportation and storage of fuel and conversion of the electricity into mechanical power. However, this calculation allows the comparison of different types of power generation. The theoretical maximum efficiency of a fuel cell approaches 100%,[73] while the theoretical maximum efficiency of internal combustion engines is approximately 58%.[74]

In practice

[edit]Values are given from 40% for acidic, 50% for molten carbonate, to 60% for alkaline, solid oxide and PEM fuel cells.[75]

Fuel cells cannot store energy like a battery,[76] except as hydrogen, but in some applications, such as stand-alone power plants based on discontinuous sources such as solar or wind power, they are combined with electrolyzers and storage systems to form an energy storage system. As of 2019, 90% of hydrogen was used for oil refining, chemicals and fertilizer production (where hydrogen is required for the Haber–Bosch process),[77] and as of 2024, more than 95% hydrogen was still produced using steam methane reformation (about 95% is grey hydrogen, most of the rest is blue hydrogen, and only about 1% is green hydrogen), a process that emits carbon dioxide.[78] In addition, the overall efficiency (electricity to hydrogen and back to electricity) of such plants (known as round-trip efficiency), using pure hydrogen and pure oxygen can be "from 35 up to 50 percent", depending on gas density and other conditions.[79] The electrolyzer/fuel cell system can store indefinite quantities of hydrogen, and is therefore suited for long-term storage.

Solid-oxide fuel cells produce heat from the recombination of the oxygen and hydrogen. The ceramic can run as hot as 800 °C (1,470 °F). This heat can be captured and used to heat water in a micro combined heat and power (m-CHP) application. When the heat is captured, total efficiency can reach 80–90% at the unit, but does not consider production and distribution losses. CHP units are being developed today for the European home market.

Professor Jeremy P. Meyers, in the Electrochemical Society journal Interface in 2008, wrote, "While fuel cells are efficient relative to combustion engines, they are not as efficient as batteries, primarily due to the inefficiency of the oxygen reduction reaction (and ... the oxygen evolution reaction, should the hydrogen be formed by electrolysis of water). ... [T]hey make the most sense for operation disconnected from the grid, or when fuel can be provided continuously. For applications that require frequent and relatively rapid start-ups ... where zero emissions are a requirement, as in enclosed spaces such as warehouses, and where hydrogen is considered an acceptable reactant, a [PEM fuel cell] is becoming an increasingly attractive choice [if exchanging batteries is inconvenient]".[80] In 2013 military organizations were evaluating fuel cells to determine if they could significantly reduce the battery weight carried by soldiers.[81]

In vehicles

[edit]In a fuel cell vehicle the tank-to-wheel efficiency is greater than 45% at low loads[82] and shows average values of about 36% when a driving cycle like the NEDC (New European Driving Cycle) is used as test procedure.[83] The comparable NEDC value for a Diesel vehicle is 22%. In 2008 Honda released a demonstration fuel cell electric vehicle (the Honda FCX Clarity) with fuel stack claiming a 60% tank-to-wheel efficiency.[84]

It is also important to take losses due to fuel production, transportation, and storage into account. Fuel cell vehicles running on compressed hydrogen may have a power-plant-to-wheel efficiency of 22% if the hydrogen is stored as high-pressure gas, and 17% if it is stored as liquid hydrogen.[85]

Applications

[edit]

Power

[edit]Stationary fuel cells are used for commercial, industrial and residential primary and backup power generation. Fuel cells are very useful as power sources in remote locations, such as spacecraft, remote weather stations, large parks, communications centers, rural locations including research stations, and in certain military applications. A fuel cell system running on hydrogen can be compact and lightweight, and have no major moving parts. Because fuel cells have no moving parts and do not involve combustion, in ideal conditions they can achieve up to 99.9999% reliability.[86] This equates to less than one minute of downtime in a six-year period.[86]

Since fuel cell electrolyzer systems do not store fuel in themselves, but rather rely on external storage units, they can be successfully applied in large-scale energy storage, rural areas being one example.[87] There are many different types of stationary fuel cells so efficiencies vary, but most are between 40% and 60% energy efficient.[6] However, when the fuel cell's waste heat is used to heat a building in a cogeneration system this efficiency can increase to 85%.[6] This is significantly more efficient than traditional coal power plants, which are only about one third energy efficient.[88] Assuming production at scale, fuel cells could save 20–40% on energy costs when used in cogeneration systems.[89] Fuel cells are also much cleaner than traditional power generation; a fuel cell power plant using natural gas as a hydrogen source would create less than one ounce of pollution (other than CO2) for every 1,000 kW·h produced, compared to 25 pounds of pollutants generated by conventional combustion systems.[90] Fuel Cells also produce 97% less nitrogen oxide emissions than conventional coal-fired power plants.

One such pilot program is operating on Stuart Island in Washington State. There the Stuart Island Energy Initiative[91] has built a complete, closed-loop system: Solar panels power an electrolyzer, which makes hydrogen. The hydrogen is stored in a 500-U.S.-gallon (1,900 L) tank at 200 pounds per square inch (1,400 kPa), and runs a ReliOn fuel cell to provide full electric back-up to the off-the-grid residence. Another closed system loop was unveiled in late 2011 in Hempstead, NY.[92]

Fuel cells can be used with low-quality gas from landfills or waste-water treatment plants to generate power and lower methane emissions. A 2.8 MW fuel cell plant in California is said to be the largest of the type.[93] Small-scale (sub-5kWhr) fuel cells are being developed for use in residential off-grid deployment.[94]

Cogeneration

[edit]Combined heat and power (CHP) fuel cell systems, including micro combined heat and power (MicroCHP) systems are used to generate both electricity and heat for homes (see home fuel cell), office building and factories. The system generates constant electric power (selling excess power back to the grid when it is not consumed), and at the same time produces hot air and water from the waste heat. As the result CHP systems have the potential to save primary energy as they can make use of waste heat which is generally rejected by thermal energy conversion systems.[95] A typical capacity range of home fuel cell is 1–3 kWel, 4–8 kWth.[96][97] CHP systems linked to absorption chillers use their waste heat for refrigeration.[98]

The waste heat from fuel cells can be diverted during the summer directly into the ground providing further cooling while the waste heat during winter can be pumped directly into the building. The University of Minnesota owns the patent rights to this type of system.[99][100]

Co-generation systems can reach 85% efficiency (40–60% electric and the remainder as thermal).[6] Phosphoric-acid fuel cells (PAFC) comprise the largest segment of existing CHP products worldwide and can provide combined efficiencies close to 90%.[101][102] Molten carbonate (MCFC) and solid-oxide fuel cells (SOFC) are also used for combined heat and power generation and have electrical energy efficiencies around 60%.[103] Disadvantages of co-generation systems include slow ramping up and down rates, high cost and short lifetime.[104][105] Also their need to have a hot water storage tank to smooth out the thermal heat production was a serious disadvantage in the domestic market place where space in domestic properties is at a great premium.[106]

Delta-ee consultants stated in 2013 that with 64% of global sales the fuel cell micro-combined heat and power passed the conventional systems in sales in 2012.[81] The Japanese ENE FARM project stated that 34.213 PEMFC and 2.224 SOFC were installed in the period 2012–2014, 30,000 units on LNG and 6,000 on LPG.[107]

Fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs)

[edit]

Automobiles

[edit]Four fuel cell electric vehicles have been introduced for commercial lease and sale: the Honda Clarity, Toyota Mirai, Hyundai ix35 FCEV, and the Hyundai Nexo. By year-end 2019, about 18,000 FCEVs had been leased or sold worldwide.[108][109] Fuel cell electric vehicles feature an average range of 505 km (314 mi) between refuelings[110] and can be refueled in about 5 minutes.[111] The U.S. Department of Energy's Fuel Cell Technology Program states that, as of 2011, fuel cells achieved 53–59% efficiency at one-quarter power and 42–53% vehicle efficiency at full power,[112] and a durability of over 120,000 km (75,000 miles) with less than 10% degradation.[113] In a 2017 Well-to-Wheels simulation analysis that "did not address the economics and market constraints", General Motors and its partners estimated that, for an equivalent journey, a fuel cell electric vehicle running on compressed gaseous hydrogen produced from natural gas could use about 40% less energy and emit 45% less greenhouse gasses than an internal combustion vehicle.[114]

In 2015, Toyota introduced its first fuel cell vehicle, the Mirai, at a price of $57,000.[115] Hyundai introduced the limited production Hyundai ix35 FCEV under a lease agreement.[116] In 2016, Honda started leasing the Honda Clarity Fuel Cell.[117] In 2018, Hyundai introduced the Hyundai Nexo, replacing the Hyundai ix35 FCEV. In 2020, Toyota introduced the second generation of its Mirai brand, improving fuel efficiency and expanding range compared to the original Sedan 2014 model.[118]

In 2024, Mirai owners filed a class action lawsuit against Toyota in California over the lack of availability of hydrogen for fuel cell electric cars, alleging, among other things, fraudulent concealment and misrepresentation as well as violations of California's false advertising law and breaches of implied warranty.[119] The same year, Hyundai recalled all 1,600 Nexo vehicles sold in the US to that time due to a risk of fuel leaks and fire from a faulty "pressure relief device".[120]

Criticism

[edit]Some commentators believe that hydrogen fuel cell cars will never become economically competitive with other technologies[121][122][123] or that it will take decades for them to become profitable.[80][124] Elon Musk, CEO of battery-electric vehicle maker Tesla Motors, stated in 2015 that fuel cells for use in cars will never be commercially viable because of the inefficiency of producing, transporting and storing hydrogen and the flammability of the gas, among other reasons.[125] In 2012, Lux Research, Inc. issued a report that stated: "The dream of a hydrogen economy ... is no nearer". It concluded that "Capital cost ... will limit adoption to a mere 5.9 GW" by 2030, providing "a nearly insurmountable barrier to adoption, except in niche applications". The analysis concluded that, by 2030, PEM stationary market will reach $1 billion, while the vehicle market, including forklifts, will reach a total of $2 billion.[124] Other analyses cite the lack of an extensive hydrogen infrastructure in the U.S. as an ongoing challenge to Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle commercialization.[82]

In 2014, Joseph Romm, the author of The Hype About Hydrogen (2005; 2025), said that FCVs still had not overcome the high fueling cost, lack of fuel-delivery infrastructure, and pollution caused by producing hydrogen. "It would take several miracles to overcome all of those problems simultaneously in the coming decades."[126] He concluded that renewable energy cannot economically be used to make hydrogen for an FCV fleet "either now or in the future."[121] Greentech Media's analyst reached similar conclusions in 2014.[127] In 2015, CleanTechnica listed some of the disadvantages of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles.[128] So did Car Throttle.[129] A 2019 video by Real Engineering noted that, notwithstanding the introduction of vehicles that run on hydrogen, using hydrogen as a fuel for cars does not help to reduce carbon emissions from transportation. The 95% of hydrogen still produced from fossil fuels releases carbon dioxide, and producing hydrogen from water is an energy-consuming process. Storing hydrogen requires more energy either to cool it down to the liquid state or to put it into tanks under high pressure, and delivering the hydrogen to fueling stations requires more energy and may release more carbon. The hydrogen needed to move a FCV a kilometer costs approximately 8 times as much as the electricity needed to move a BEV the same distance.[130]

A 2020 assessment concluded that hydrogen vehicles are still only 38% efficient, while battery EVs are 80% efficient.[131] In 2021 CleanTechnica concluded that (a) hydrogen cars remain far less efficient than electric cars; (b) grey hydrogen – hydrogen produced with polluting processes – makes up the vast majority of available hydrogen; (c) delivering hydrogen would require building a vast and expensive new delivery and refueling infrastructure; and (d) the remaining two "advantages of fuel cell vehicles – longer range and fast fueling times – are rapidly being eroded by improving battery and charging technology."[132] A 2022 study in Nature Electronics agreed.[133] A 2023 study by the Centre for International Climate and Environmental Research (CICERO) estimated that leaked hydrogen has a global warming effect 11.6 times stronger than CO2.[134]

Buses

[edit]

As of August 2011[update], there were about 100 fuel cell buses in service around the world.[135] Most of these were manufactured by UTC Power, Toyota, Ballard, Hydrogenics, and Proton Motor. UTC buses had driven more than 970,000 km (600,000 miles) by 2011.[136] Fuel cell buses have from 39% to 141% higher fuel economy than diesel buses and natural gas buses.[114][137]

As of 2019[update], the NREL was evaluating several current and planned fuel cell bus projects in the U.S.[138]

Trains

[edit]Train operators may use hydrogen fuel cells in trains in an effort to save the costs of installing overhead electrification and to maintain the range offered by diesel trains. They have encountered expenses, however, due to fuel cells in trains lasting only three years, maintenance of the hydrogen tank and the additional need for batteries as a power buffer.[139][140] In 2018, the first fuel cell-powered trains, the Alstom Coradia iLint multiple units, began running on the Buxtehude–Bremervörde–Bremerhaven–Cuxhaven line in Germany.[141] Hydrogen trains have also been introduced in Sweden[142] and the UK.[143]

Trucks

[edit]In December 2020, Toyota and Hino Motors, together with Seven-Eleven (Japan), FamilyMart and Lawson announced that they have agreed to jointly consider introducing light-duty fuel cell electric trucks (light-duty FCETs).[144] Lawson started testing for low temperature delivery at the end of July 2021 in Tokyo, using a Hino Dutro in which the Toyota Mirai fuel cell is implemented. FamilyMart started testing in Okazaki city.[145]

In August 2021, Toyota announced their plan to make fuel cell modules at its Kentucky auto-assembly plant for use in zero-emission big rigs and heavy-duty commercial vehicles. They plan to begin assembling the electrochemical devices in 2023.[146]

In October 2021, Daimler Truck's fuel cell based truck received approval from German authorities for use on public roads.[147]

Forklifts

[edit]A fuel cell forklift (also called a fuel cell lift truck) is a fuel cell-powered industrial forklift truck used to lift and transport materials. In 2013 there were over 4,000 fuel cell forklifts used in material handling in the US,[148] of which 500 received funding from DOE (2012).[149][150] As of 2024, approximately 50,000 hydrogen forklifts are in operation worldwide (the bulk of which are in the U.S.), as compared with 1.2 million battery electric forklifts that were purchased in 2021.[151]

Most companies in Europe and the US do not use petroleum-powered forklifts, as these vehicles work indoors where emissions must be controlled and instead use electric forklifts.[152][153] Fuel cell-powered forklifts can be refueled in 3 minutes and they can be used in refrigerated warehouses, where their performance is not degraded by lower temperatures. The FC units are often designed as drop-in replacements.[154][155]

Motorcycles and bicycles

[edit]In 2005, a British manufacturer of hydrogen-powered fuel cells, Intelligent Energy (IE), produced the first working hydrogen-run motorcycle called the ENV (Emission Neutral Vehicle). The motorcycle holds enough fuel to run for four hours, and to travel 160 km (100 miles) in an urban area, at a top speed of 80 km/h (50 mph).[156] In 2004 Honda developed a fuel cell motorcycle that utilized the Honda FC Stack.[157][158]

Other examples of motorbikes[159] and bicycles[160] that use hydrogen fuel cells include the Taiwanese company APFCT's scooter[161] using the fueling system from Italy's Acta SpA[162] and the Suzuki Burgman scooter with an IE fuel cell that received EU Whole Vehicle Type Approval in 2011.[163] Suzuki Motor Corp. and IE have announced a joint venture to accelerate the commercialization of zero-emission vehicles.[164]

Airplanes

[edit]In 2003, the world's first propeller-driven airplane to be powered entirely by a fuel cell was flown. The fuel cell was a stack design that allowed the fuel cell to be integrated with the plane's aerodynamic surfaces.[165] Fuel cell-powered unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) include a Horizon fuel cell UAV that set the record distance flown for a small UAV in 2007.[166] Boeing researchers and industry partners throughout Europe conducted experimental flight tests in February 2008 of a manned airplane powered only by a fuel cell and lightweight batteries. The fuel cell demonstrator airplane, as it was called, used a proton-exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cell/lithium-ion battery hybrid system to power an electric motor, which was coupled to a conventional propeller.[167]

In 2009, the Naval Research Laboratory's (NRL's) Ion Tiger utilized a hydrogen-powered fuel cell and flew for 23 hours and 17 minutes.[168] Fuel cells are also being tested and considered to provide auxiliary power in aircraft, replacing fossil fuel generators that were previously used to start the engines and power on board electrical needs, while reducing carbon emissions.[169][170][failed verification] In 2016 a Raptor E1 drone made a successful test flight using a fuel cell that was lighter than the lithium-ion battery it replaced. The flight lasted 10 minutes at an altitude of 80 metres (260 ft), although the fuel cell reportedly had enough fuel to fly for two hours. The fuel was contained in approximately 100 solid 1 square centimetre (0.16 sq in) pellets composed of a proprietary chemical within an unpressurized cartridge. The pellets are physically robust and operate at temperatures as warm as 50 °C (122 °F). The cell was from Arcola Energy.[171]

Lockheed Martin Skunk Works Stalker is an electric UAV powered by solid oxide fuel cell.[172]

Boats

[edit]

The Hydra, a 22-person fuel cell boat operated from 1999 to 2001 on the Rhine river near Bonn, Germany,[173] and was used as a ferry boat in Ghent, Belgium, during an electric boat conference in 2000. It was fully certified by the Germanischer Lloyd for passenger transport.[174] The Zemship, a small passenger ship, was produced in 2003 to 2013. It used a 100 kW Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFC) with 7 lead gel batteries. With these systems, alongside 12 storage tanks, fuel cells provided an energy capacity of 560 V and 234 kWh.[175] Made in Hamburg, Germany, the FCS Alsterwasser, revealed in 2008, was one of the first passenger ships powered by fuel cells and could carry 100 passengers. The hybrid fuel cell technology that powered this ship was produced by Proton Motor Fuel Cell GmbH.[176]

In 2010, the MF Vågen was first produced, utilizing 12 kW fuel cells and 2- to 3-kilogram metal hydride hydrogen storage. It also utilizes 25 kWh lithium batteries and a 10 kW DC motor.[175] The Hornblower Hybrid debuted in 2012. It utilizes a diesel generator, batteries, photovoltaics, wind power, and fuel cells for energy.[175] Made in Bristol, a 12-passenger hybrid ferry, Hydrogenesis, has been in operation since 2012.[175] The SF-BREEZE is a two-motor boat that utilizes 41 × 120 kW fuel cells. With a type C storage tank, the pressurized vessel can maintain 1200 kg of LH2. These ships are still in operation today.[175] In Norway, the first ferry powered by fuel cells running on liquid hydrogen was scheduled for its first test drives in December 2022.[177][178]

The Type 212 submarines of the German and Italian navies use fuel cells to remain submerged for weeks without the need to surface.[179] The U212A is a non-nuclear submarine developed by German naval shipyard Howaldtswerke Deutsche Werft.[180] The system consists of nine PEM fuel cells, providing between 30 kW and 50 kW each. The ship is silent, giving it an advantage in the detection of other submarines.[181]

Portable power systems

[edit]Portable fuel cell systems are generally classified as weighing under 10 kg and providing power of less than 5 kW.[182] The potential market size for smaller fuel cells was estimated in 2002 at around $10 billion.[183] Within this market two groups have been identified. The first is the microfuel cell market, in the 1-50 W range for power smaller electronic devices. The second is the 1-5 kW range of generators for larger scale power generation (e.g. military outposts, remote oil fields). Microfuel cells are primarily aimed at penetrating the market for phones and laptops.[183]

Portable power systems that use fuel cells can be used in the leisure sector (i.e. RVs, cabins, marine), industry (i.e. power for remote locations including gas/oil wellsites, communication towers, security, weather stations), and the military. SFC Energy is a German manufacturer of direct methanol fuel cells for a variety of portable power systems.[184] Ensol Systems Inc. is an integrator of portable power systems, using the SFC Energy DMFC.[185] The key advantage of fuel cells in this market is the great power generation per weight. While fuel cells can be expensive, for remote locations that require dependable energy fuel cells hold great power.[182]

Other applications

[edit]- Providing power for base stations or cell sites[186][187]

- Emergency power systems are a type of fuel cell system, which may include lighting, generators and other apparatus, to provide backup resources in a crisis or when regular systems fail. They find uses in a wide variety of settings from residential homes to hospitals, scientific laboratories, data centers,[188]

- Telecommunication[189] equipment and modern naval ships.

- An uninterrupted power supply (UPS) provides emergency power and, depending on the topology, provide line regulation as well to connected equipment by supplying power from a separate source when utility power is not available. Unlike a standby generator, it can provide instant protection from a momentary power interruption.

- Smartphones, laptops and tablets for use in locations where AC charging may not be readily available.

- Portable charging docks for small electronics (e.g. a belt clip that charges a cell phone or PDA).

- Small heating appliances[190]

- Food preservation, achieved by exhausting the oxygen and automatically maintaining oxygen exhaustion in a shipping container, containing, for example, fresh fish.[191]

- Sensors, including in Breathalyzers, where the amount of voltage generated by a fuel cell is used to determine the concentration of fuel (alcohol) in the sample.[192]

Fueling stations

[edit]

According to FuelCellsWorks, an industry group, at the end of 2019, 330 hydrogen refueling stations were open to the public worldwide.[193] As of June 2020, there were 178 publicly available hydrogen stations in operation in Asia.[194] 114 of these were in Japan.[194] There were at least 177 stations in Europe, and about half of these were in Germany.[195][196] There were 44 publicly accessible stations in the US, 42 of which were located in California.[197]

A hydrogen fueling station costs between $1 million and $4 million to build.[198]

Social Implications

[edit]As of 2023, technological barriers to fuel cell adoption remain.[199] Fuel cells are primarily for material handling in warehouses, distribution centers, and manufacturing facilities.[200] They are projected to be useful and sustainable in a wider range applications.[201] But current applications do not often reach lower-income communities,[202] though some attempts at inclusivity are being made, for example in accessibility.[203]

Markets and economics

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (July 2025) |

In 2012, fuel cell industry revenues exceeded $1 billion market value worldwide, with Asian pacific countries shipping more than 3/4 of the fuel cell systems worldwide.[204] There were 140,000 fuel cell stacks shipped globally in 2010, up from 11,000 shipments in 2007, and from 2011 to 2012 worldwide fuel cell shipments had an annual growth rate of 85%.[205] Tanaka Kikinzoku expanded its manufacturing facilities in 2011.[206] Approximately 50% of fuel cell shipments in 2010 were stationary fuel cells, up from about a third in 2009, and the four dominant producers in the Fuel Cell Industry were the United States, Germany, Japan and South Korea.[207] The Department of Energy Solid State Energy Conversion Alliance found that, as of January 2011, stationary fuel cells generated power at approximately $724 to $775 per kilowatt installed.[208] In 2011, Bloom Energy, a major fuel cell supplier, said that its fuel cells generated power at 9–11 cents per kilowatt-hour, including the price of fuel, maintenance, and hardware.[209][210]

In 2016, Samsung "decided to drop fuel cell-related business projects, as the outlook of the market isn't good".[211]

Research and development

[edit]- 2013: British firm ACAL Energy developed a fuel cell that it said could run for 10,000 hours in simulated driving conditions.[212] It asserted that the cost of fuel cell construction can be reduced to $40/kW (roughly $9,000 for 300 HP).[213]

- 2014: Researchers in Imperial College London developed a new method for regeneration of hydrogen sulfide contaminated PEFCs.[214] They recovered 95–100% of the original performance of a hydrogen sulfide contaminated PEFC. They were successful in rejuvenating a SO2 contaminated PEFC too.[215] This regeneration method is applicable to multiple cell stacks.[216]

- 2019: U.S. Army Research Laboratory researchers developed a two part in-situ hydrogen generation fuel cell, one for hydrogen generation and the other for electric power generation through an internal hydrogen/air power plant.[217]

- 2022: Researchers from University of Delaware developed a hydrogen-powered fuel cell projected to function at lower costs and operate at roughly $1.4/kW. This design removes carbon dioxide from the air feed of hydroxide exchange membrane fuel cells.[218]

- 2024 KAIST researchers developed a method to create a protonic fuel cell relying on laminating slurries in a tape casting, then sintering the laminated structure. The three different slurries were created by using Resonant Acoustic Mixing (RAM) before deposition.[219]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Saikia, Kaustav; Kakati, Biraj Kumar; Boro, Bibha; Verma, Anil (2018). "Current Advances and Applications of Fuel Cell Technologies". Recent Advancements in Biofuels and Bioenergy Utilization. Singapore: Springer. pp. 303–337. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-1307-3_13. ISBN 978-981-13-1307-3.

- ^ Khurmi, R. S. (2014). Material Science. S. Chand & Company. ISBN 978-81-219-0146-8.

- ^ Winter, Martin; Brodd, Ralph J. (28 September 2004). "What Are Batteries, Fuel Cells, and Supercapacitors?". Chemical Reviews. 104 (10): 4245–4270. doi:10.1021/cr020730k. PMID 15669155. S2CID 3091080.

- ^ "Bronx Hydrogen Fuel Cell Bus". Empire Clean Cities. Retrieved 13 April 2024.

- ^ Nice, Karim and Strickland, Jonathan. "How Fuel Cells Work: Polymer Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells". How Stuff Works, accessed 4 August 2011

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Types of Fuel Cells" Archived 9 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Department of Energy EERE website, accessed 4 August 2011

- ^ Grove, W. R. (1838). "On a new voltaic combination". The London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 3rd series. 13 (84): 430–431. doi:10.1080/14786443808649618. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ^ Grove, William Robert (1839). "On Voltaic Series and the Combination of Gases by Platinum". Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 3rd series. 14 (86–87): 127–130. doi:10.1080/14786443908649684.

- ^ Schœnbein (1839). "On the voltaic polarization of certain solid and fluid substances" (PDF). The London and Edinburgh Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 3rd series. 14 (85): 43–45. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ^ Grove, William Robert (1842). "On a Gaseous Voltaic Battery". The London, Edinburgh and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 3rd series. 21 (140): 417–420. doi:10.1080/14786444208621600.

- ^ Larminie, James; Dicks, Andrew. Fuel Cell Systems Explained (PDF).[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "The Brits who bolstered the Moon landings". BBC. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ "Apollo 11 mission 50 years on: The Cambridge scientist who helped put man on the moon". Cambridge Independent. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ "Fuel Cell Project: PEM Fuel Cells photo #2". americanhistory.si.edu.

- ^ "Collecting the History of Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells". americanhistory.si.edu.

- ^ "The PureCell Model 400 – Product Overview". UTC Power. Archived from the original on 11 December 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ "S.Res.217 – A resolution designating October 8, 2015, as "National Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Day"". Congress.gov. 29 September 2015.

- ^ "Fuel Cells - EnergyGroove.net". EnergyGroove.net. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Reliable High Performance Textile Materials". Tex Tech Industries. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ Larminie, James (1 May 2003). Fuel Cell Systems Explained, Second Edition. SAE International. ISBN 978-0-7680-1259-0.

- ^ Kakati, B. K.; Deka, D. (2007). "Effect of resin matrix precursor on the properties of graphite composite bipolar plate for PEM fuel cell". Energy & Fuels. 21 (3): 1681–1687. Bibcode:2007EnFue..21.1681K. doi:10.1021/ef0603582.

- ^ "LEMTA – Our fuel cells". Perso.ensem.inpl-nancy.fr. Archived from the original on 21 June 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ Yin, Xi; Lin, Ling; Chung, Hoon T; Komini Babu, Siddharth; Martinez, Ulises; Purdy, Geraldine M; Zelenay, Piotr (4 August 2017). "Effects of MEA Fabrication and Ionomer Composition on Fuel Cell Performance of PGM-Free ORR Catalyst". ECS Transactions. 77 (11): 1273–1281. Bibcode:2017ECSTr..77k1273Y. doi:10.1149/07711.1273ecst. OSTI 1463547.

- ^ Anne-Claire Dupuis, Progress in Materials Science, Volume 56, Issue 3, March 2011, pp. 289–327

- ^ "Measuring the relative efficiency of hydrogen energy technologies for implementing the hydrogen economy 2010" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2013.

- ^ Kakati, B. K.; Mohan, V. (2008). "Development of low cost advanced composite bipolar plate for P.E.M. fuel cell". Fuel Cells. 08 (1): 45–51. doi:10.1002/fuce.200700008. S2CID 94469845.

- ^ Kakati, B. K.; Deka, D. (2007). "Differences in physico-mechanical behaviors of resol and novolac type phenolic resin based composite bipolar plate for proton exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cell". Electrochimica Acta. 52 (25): 7330–7336. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2007.06.021.

- ^ a b Coletta, Vitor, et al. "Cu-Modified SrTiO 3 Perovskites Toward Enhanced Water-Gas Shift Catalysis: A Combined Experimental and Computational Study" , ACS Applied Energy Materials (2021), vol. 4, issue 1, pp. 452–461

- ^ Spendelow, Jacob and Jason Marcinkoski. "Fuel Cell System Cost – 2013" Archived 2 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, DOE Fuel Cell Technologies Office, 16 October 2013 (archived version)

- ^ "Ballard Power Systems: Commercially Viable Fuel Cell Stack Technology Ready by 2010". 29 March 2005. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2007.

- ^ Online, Science (2 August 2008). "2008 – Cathodes in fuel cells". Abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 6 August 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ Wang, Shuangyin (2011). "Polyelectrolyte Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes as Efficient Metal-free Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 133 (14): 5182–5185. Bibcode:2011JAChS.133.5182W. doi:10.1021/ja1112904. PMID 21413707. S2CID 207063759.

- ^ Notter, Dominic A.; Kouravelou, Katerina; Karachalios, Theodoros; Daletou, Maria K.; Haberland, Nara Tudela (2015). "Life cycle assessment of PEM FC applications: electric mobility and μ-CHP". Energy Environ. Sci. 8 (7): 1969–1985. Bibcode:2015EnEnS...8.1969N. doi:10.1039/C5EE01082A.

- ^ "Water_and_Air_Management". Ika.rwth-aachen.de. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ Andersson, M.; Beale, S. B.; Espinoza, M.; Wu, Z.; Lehnert, W. (15 October 2016). "A review of cell-scale multiphase flow modeling, including water management, in polymer electrolyte fuel cells". Applied Energy. 180: 757–778. Bibcode:2016ApEn..180..757A. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.08.010.

- ^ "Progress and Accomplishments in Hydrogen and Fuel Cells" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Collecting the History of Phosphoric Acid Fuel Cells". americanhistory.si.edu.

- ^ "Phosphoric Acid Fuel Cells". scopeWe - a Virtual Engineer. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- ^ Haile, Sossina M.; Chisholm, Calum R. I.; Sasaki, Kenji; Boysen, Dane A.; Uda, Tetsuya (11 December 2006). "Solid acid proton conductors: from laboratory curiosities to fuel cell electrolytes" (PDF). Faraday Discussions. 134: 17–39. Bibcode:2007FaDi..134...17H. doi:10.1039/B604311A. ISSN 1364-5498. PMID 17326560. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 August 2017.

- ^ Williams, K.R. (1 February 1994). "Francis Thomas Bacon. 21 December 1904 – 24 May 1992". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 39: 2–9. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1994.0001. S2CID 71613260.

- ^ Srivastava, H. C. Nootan ISC Chemistry (12th) Edition 18, pp. 458–459, Nageen Prakashan (2014) ISBN 9789382319399

- ^ Stambouli, A. Boudghene (2002). "Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs): a review of an environmentally clean and efficient source of energy". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 6 (5): 433–455. Bibcode:2002RSERv...6..433S. doi:10.1016/S1364-0321(02)00014-X.

- ^ "Solid Oxide Fuel Cell (SOFC)". FCTec website', accessed 4 August 2011 Archived 8 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Methane Fuel Cell Subgroup". University of Virginia. 2012. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ^ A Kulkarni; FT Ciacchi; S Giddey; C Munnings; SPS Badwal; JA Kimpton; D Fini (2012). "Mixed ionic electronic conducting perovskite anode for direct carbon fuel cells". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 37 (24): 19092–19102. Bibcode:2012IJHE...3719092K. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2012.09.141.

- ^ S. Giddey; S.P.S. Badwal; A. Kulkarni; C. Munnings (2012). "A comprehensive review of direct carbon fuel cell technology". Progress in Energy and Combustion Science. 38 (3): 360–399. Bibcode:2012PECS...38..360G. doi:10.1016/j.pecs.2012.01.003.

- ^ Hill, Michael. "Ceramic Energy: Material Trends in SOFC Systems" Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Ceramic Industry, 1 September 2005.

- ^ "The Ceres Cell" Archived 13 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Ceres Power website, accessed 4 August 2011

- ^ a b c "Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell Technology". U.S. Department of Energy, accessed 9 August 2011

- ^ "Molten Carbonate Fuel Cells (MCFC)". FCTec.com, accessed 9 August 2011 Archived 3 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Products". FuelCell Energy, accessed 9 August 2011 Archived 11 January 2013 at archive.today

- ^ U.S. patent 8,354,195

- ^ Huang, Wengang; Zulkifli, Muhammad Yazid Bin; Chai, Milton; Lin, Rijia; Wang, Jingjing; Chen, Yuelei; Chen, Vicki; Hou, Jingwei (August 2023). "Recent advances in enzymatic biofuel cells enabled by innovative materials and techniques". Exploration. 3 (4) 20220145. doi:10.1002/EXP.20220145. PMC 10624391. PMID 37933234.

- ^ Babanova, Sofia (2009). "Biofuel Cells – Alternative Power Sources". International Scientific Conference (FMNS2013), Blagoevgrad (Bulgaria).

- ^ Kižys, Kasparas; Zinovičius, Antanas; Jakštys, Baltramiejus; Bružaitė, Ingrida; Balčiūnas, Evaldas; Petrulevičienė, Milda; Ramanavičius, Arūnas; Morkvėnaitė-Vilkončienė, Inga (3 February 2023). "Microbial Biofuel Cells: Fundamental Principles, Development and Recent Obstacles". Biosensors. 13 (2): 221. doi:10.3390/bios13020221. PMC 9954062. PMID 36831987.

- ^ Kwon, Cheong Hoon; Ko, Yongmin; Shin, Dongyeeb; Kwon, Minseong; Park, Jinho; Bae, Wan Ki; Lee, Seung Woo; Cho, Jinhan (26 October 2018). "High-power hybrid biofuel cells using layer-by-layer assembled glucose oxidase-coated metallic cotton fibers". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 4479. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.4479K. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06994-5. PMC 6203850. PMID 30367069.

- ^ Cai, Jingsheng; Shen, Fei; Zhao, Jianqing; Xiao, Xinxin (February 2024). "Enzymatic biofuel cell: A potential power source for self-sustained smart textiles". iScience. 27 (2) 108998. Bibcode:2024iSci...27j8998C. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2024.108998. PMC 10850773. PMID 38333690.

- ^ Wang, Linlin; Wu, Xiaoge; Su, B. S. Qi-wen; Song, Rongbin; Zhang, Jian-Rong; Zhu, Jun-Jie (August 2021). "Enzymatic Biofuel Cell: Opportunities and Intrinsic Challenges in Futuristic Applications". Advanced Energy and Sustainability Research. 2 (8) 2100031. Bibcode:2021AdESR...200031W. doi:10.1002/aesr.202100031.

- ^ "Fuel Cell Comparison Chart" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ^ E. Harikishan Reddy; Jayanti, S (15 December 2012). "Thermal management strategies for a 1 kWe stack of a high temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cell". Applied Thermal Engineering. 48: 465–475. Bibcode:2012AppTE..48..465H. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2012.04.041.

- ^ a b c d e Badwal, Sukhvinder P. S.; Giddey, Sarbjit S.; Munnings, Christopher; Bhatt, Anand I.; Hollenkamp, Anthony F. (24 September 2014). "Emerging electrochemical energy conversion and storage technologies". Frontiers in Chemistry. 2: 79. Bibcode:2014FrCh....2...79B. doi:10.3389/fchem.2014.00079. PMC 4174133. PMID 25309898.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Fuel Cell Technologies Program: Glossary" Archived 23 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Department of Energy Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Fuel Cell Technologies Program. 7 July 2011. Accessed 3 August 2011.

- ^ "Aqueous Solution". Merriam-Webster Free Online Dictionary

- ^ "Matrix". Merriam-Webster Free Online Dictionary

- ^ Araya, Samuel Simon (2012). High temperature PEM fuel cells - degradation & durability: dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Engineering and Science at Aalborg University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Aalborg: Aalborg University, Department of Energy Technology. ISBN 978-87-92846-14-3. OCLC 857436369.

- ^ "Solution". Merriam-Webster Free Online Dictionary

- ^ "Comparison of Fuel Cell Technologies" Archived 1 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Department of Energy, Energy Efficiency and Fuel Cell Technologies Program, February 2011, accessed 4 August 2011

- ^ "Benchmarking a 2018 Toyota Camry 2.5-Liter Atkinson Cycle Engine with Cooled-EGR" (PDF). SAE. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ Yang, Dongsheng; Lu, Guoxiang; Gong, Zewen; Qiu, An; Bouaita, Abdelhamid (2021). "Development of 43% Brake Thermal Efficiency Gasoline Engine for BYD DM-i Plug-in Hybrid". SAE Technical Paper Series. Vol. 1. SAE. doi:10.4271/2021-01-1241. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ "New Benchmarks for Steam Turbine Efficiency". August 2002. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "All Units of Nishi-Nagoya Thermal Power Station Now in Operation". Toshiba Energy Systems & Solutions Corporation. 30 March 2018.

- ^ "Chubu Electric Power's Nishi-Nagoya Thermal Power Station Unit 7-1 Recognized by Guinness World Records as World's Most Efficient Combined Cycle Power Plant: Achieved 63.08% Power Generation Efficiency". Press Release 2018. Chubu Electric. 27 March 2018.

- ^ Haseli, Y. (3 May 2018). "Maximum conversion efficiency of hydrogen fuel cells". International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 43 (18): 9015–9021. Bibcode:2018IJHE...43.9015H. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.03.076. ISSN 0360-3199.

- ^ "Fuel Cell Efficiency" Archived 9 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. World Energy Council, 17 July 2007, accessed 4 August 2011

- ^ "Fuel Cells" (PDF). November 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ^ "Batteries, Supercapacitors, and Fuel Cells: Scope". Science Reference Services. 20 August 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ "Realising the hydrogen economy" Archived 5 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine,Power Technology, 11 October 2019

- ^ "Ask MIT Climate: How Clean Is Green Hydrogen?", MIT, February 27, 2024

- ^ Garcia, Christopher P.; et al. (January 2006). "Round Trip Energy Efficiency of NASA Glenn Regenerative Fuel Cell System". Preprint. p. 5. hdl:2060/20060008706.

- ^ a b Meyers, Jeremy P. "Getting Back Into Gear: Fuel Cell Development After the Hype". The Electrochemical Society Interface, Winter 2008, pp. 36–39, accessed 7 August 2011

- ^ a b "The fuel cell industry review 2013" (PDF).

- ^ a b Eberle, Ulrich and Rittmar von Helmolt. "Sustainable transportation based on electric vehicle concepts: a brief overview". Energy & Environmental Science, Royal Society of Chemistry, 14 May 2010, accessed 2 August 2011

- ^ Von Helmolt, R.; Eberle, U (20 March 2007). "Fuel Cell Vehicles:Status 2007". Journal of Power Sources. 165 (2): 833–843. Bibcode:2007JPS...165..833V. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2006.12.073.

- ^ "Honda FCX Clarity – Fuel cell comparison". Honda. Archived from the original on 3 January 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ "Efficiency of Hydrogen PEFC, Diesel-SOFC-Hybrid and Battery Electric Vehicles" (PDF). 15 July 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2006. Retrieved 23 May 2007.

- ^ a b "Fuel Cell Basics: Benefits". Fuel Cells 2000. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2007.

- ^ "Fuel Cell Basics: Applications" Archived 15 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Fuel Cells 2000. Accessed 2 August 2011.

- ^ "Energy Sources: Electric Power". U.S. Department of Energy. Accessed 2 August 2011.

- ^ "2008 Fuel Cell Technologies Market Report" Archived 4 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Bill Vincent of the Breakthrough Technologies Institute, Jennifer Gangi, Sandra Curtin, and Elizabeth Delmont. Department of Energy Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. June 2010.

- ^ U.S. Fuel Cell Council Industry Overview 2010, p. 12. U.S. Fuel Cell Council. 2010.

- ^ "Stuart Island Energy Initiative". Siei.org. Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2009. – gives extensive technical details

- ^ "Town's Answer to Clean Energy is Blowin' in the Wind: New Wind Turbine Powers Hydrogen Car Fuel Station". Town of Hempstead. Archived from the original on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ World's Largest Carbon Neutral Fuel Cell Power Plant Archived 28 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 16 October 2012

- ^ Upstart Power Announces Investment for Residential Fuel Cell Technology from Clean Tech Leaders Archived 22 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, 16 December 2020

- ^ "Reduction of residential carbon dioxide emissions through the use of small cogeneration fuel cell systems – Combined heat and power systems". IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme (IEAGHG). 11 November 2008. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ "Reduction of residential carbon dioxide emissions through the use of small cogeneration fuel cell systems – Scenario calculations". IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme (IEAGHG). 11 November 2008. Archived from the original on 26 October 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ "cogen.org – body shop in nassau county".

- ^ "Fuel Cells and CHP" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2012.

- ^ "Patent 7,334,406". Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- ^ "Geothermal Heat, Hybrid Energy Storage System". Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2011.