Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Polypectomy.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Polypectomy

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

In medicine, a polypectomy is the surgical removal of an abnormal growth of tissue called a polyp. Polypectomy can be performed by excision if the polyp is external (on the skin).[1][additional citation(s) needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Li, Chao; Ellsmere, James (1 January 2019). "Chapter 57 - Diagnostic and Therapeutic Endoscopy of the Stomach and Small Bowel". Shackelford's Surgery of the Alimentary Tract, 2 Volume Set (Eighth ed.). Elsevier. pp. 647–662. ISBN 978-0-323-40232-3. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

Polypectomy

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

A polypectomy is a minimally invasive medical procedure used to remove polyps, which are abnormal growths of tissue that protrude from the mucous membrane of various organs, most commonly the colon, uterus, or nasal passages, in order to prevent potential progression to cancer.[1] These growths are often benign but can be precancerous, and their removal allows for pathological examination to assess malignancy risk.[2] The procedure is typically performed endoscopically, using specialized instruments inserted through natural body openings, making it a safer alternative to open surgery for most cases.[3]

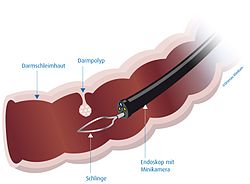

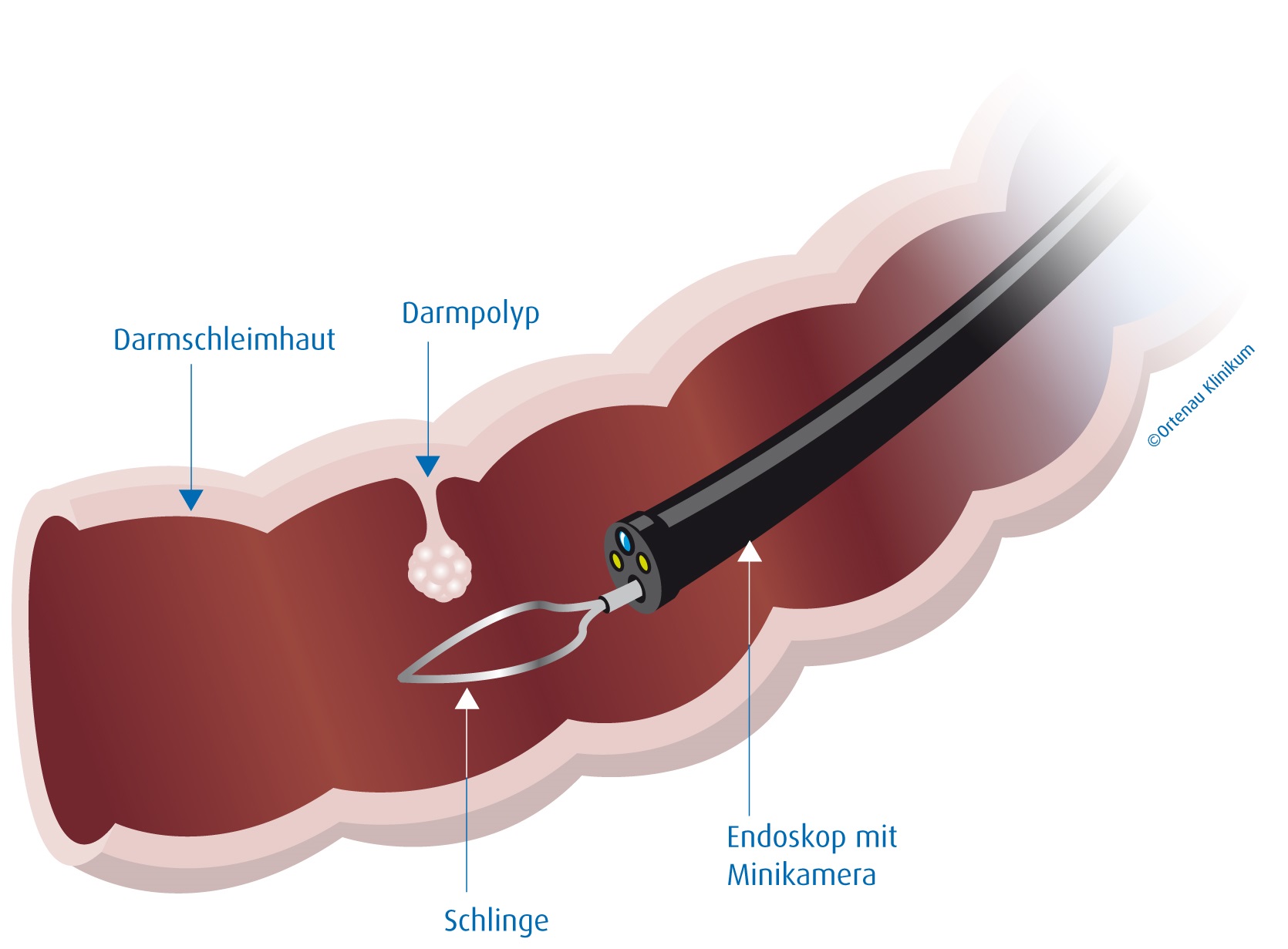

In the context of colorectal health, polypectomy is a cornerstone of preventive care, often conducted during a routine colonoscopy where a flexible tube equipped with a camera (colonoscope) is inserted through the rectum to visualize and excise polyps.[2] Techniques vary by polyp size and location: small polyps (under 5 mm) are snared with a wire loop or grasped with biopsy forceps, while larger ones may require endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), involving injection of fluid to lift the polyp before cutting, or even advanced methods like endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for complex lesions.[1] Electrocautery is commonly applied to seal blood vessels and minimize bleeding during removal.[3] This intervention has significantly lowered colorectal cancer incidence and mortality, as removing adenomas—the most common precancerous polyps—interrupts their progression to malignancy.[2]

While generally safe, polypectomy carries risks including bleeding (occurring in about 1.5 per 1,000 procedures), perforation of the colon wall (around 0.3 per 1,000), and infection, particularly in patients on blood thinners or with larger polyps.[2] Recovery is typically rapid, with patients resuming normal activities within days, though follow-up surveillance colonoscopies are recommended based on polyp characteristics—such as number, size, and histology—to monitor for recurrence.[3] For uterine or nasal polyps, similar endoscopic approaches apply, tailored to the site, emphasizing polypectomy's versatility in gynecological and otolaryngological settings.[1]