Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Propofol

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Diprivan, others[1] |

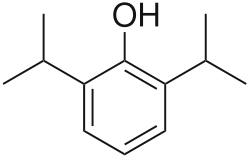

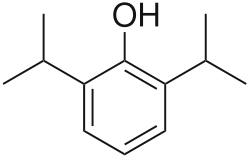

| Other names | 2,6-Diisopropylphenol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Physical: Very high Psychological: no data |

| Addiction liability | Moderate[2] |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| Drug class | GABAA receptor agonist; sedative; general anesthetic |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 95–99% |

| Metabolism | Liver glucuronidation |

| Onset of action | 15–30 seconds[5] |

| Elimination half-life | 1.5–31 hours[5] |

| Duration of action | ~5–10 minutes[5] |

| Excretion | Liver |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.016.551 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H18O |

| Molar mass | 178.275 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Solubility in water | ΔGsolvH2O = -4.39kcal/mol[6] |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Propofol[7] is the active component of an intravenous anesthetic formulation used for induction and maintenance of general anesthesia. The formulation was approved under the brand name Diprivan. Numerous generic versions have since been released. Intravenous administration is used to induce unconsciousness, after which anesthesia may be maintained using a combination of medications. It is manufactured as part of a sterile injectable emulsion formulation using soybean oil and lecithin, giving it a white milky coloration.[8]

Compared to other anesthetic agents, recovery from propofol-induced anesthesia is generally rapid and associated with less frequent side effects[9][10] (e.g., drowsiness, nausea, vomiting). Propofol may be used prior to diagnostic procedures requiring anesthesia, in the management of refractory status epilepticus, and for induction or maintenance of anesthesia prior to and during surgeries. It may be administered as a bolus or an infusion, or as a combination of the two.

First synthesized in 1973 by John B. Glen, a British veterinary anesthesiologist working for Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI, later AstraZeneca),[11] propofol was introduced for therapeutic use as a lipid emulsion in the United Kingdom and New Zealand in 1986. Propofol (Diprivan) received FDA approval in October 1989. It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[12]

Uses

[edit]Anesthesia

[edit]To induce general anesthesia, propofol is the drug used almost exclusively, having largely replaced sodium thiopental.[13]

It is often administered as part of an anesthesia maintenance technique called total intravenous anesthesia, using either manually programmed infusion pumps or computer-controlled infusion pumps in a process called target controlled infusion (TCI).[14]

Propofol is also used to sedate people who are receiving mechanical ventilation but not undergoing surgery, such as patients in the intensive care unit.[15] In critically ill patients, propofol is superior to lorazepam both in effectiveness and overall cost.[16] Propofol is relatively inexpensive compared to medications of similar use due to shorter ICU stay length.[16] One of the reasons propofol is thought to be more effective (although it has a longer half-life than lorazepam) is that studies have found that benzodiazepines like midazolam and lorazepam tend to accumulate in critically ill patients, prolonging sedation.[16]

Propofol has also been suggested as a sleep aid in critically ill adults in an ICU setting; however, the effectiveness of this medicine in replicating the mental and physical aspects of sleep for people in the ICU is not clear.[15]

Propofol can be administered via a peripheral IV or central line. Propofol is often paired with fentanyl (for pain relief) in intubated and sedated people.[17] The two drugs are molecularly compatible in an IV mixture form.[17]

Propofol is also used to deepen anesthesia to relieve laryngospasm. It may be used alone or followed by succinylcholine. Its use can avoid the need for paralysis and in some instances the potential side-effects of succinylcholine.[18]

Routine procedural sedation

[edit]Propofol is safe and effective for gastrointestinal endoscopy procedures (colonoscopies etc.). Its use in these settings results in a faster recovery compared to midazolam.[19] It can also be combined with opioids or benzodiazepines.[20][21][22] Because of its rapid induction and recovery time, propofol is also widely used for sedation of infants and children undergoing MRI procedures.[23] It is also often used in combination with ketamine with minimal side effects.[24]

COVID-19

[edit]In March 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for Propofol‐Lipuro 1% to maintain sedation via continuous infusion in people older than sixteen with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 who require mechanical ventilation in an intensive care unit ICU setting.[25][26][27][28] During the public health emergency, it was considered unfeasible to limit Fresenius Propoven 2% Emulsion or Propofol-Lipuro 1% to patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, so it was made available to all ICU patients under mechanical ventilation.[28] This EUA has since been revoked.[29]

Status epilepticus

[edit]Status epilepticus may be defined as seizure activity lasting beyond five minutes and needing anticonvulsant medication. Several guidelines recommend the use of propofol for the treatment of refractory status epilepticus.[30]

Other uses

[edit]Assisted death in Canada

[edit]A lethal dose of propofol is used for medical assistance in dying in Canada to quickly induce deep coma and death, but rocuronium is always given as a paralytic ensuring death, even when the patient has died as a result of initial propofol overdose.[31]

Capital punishment

[edit]The use of propofol as part of an execution protocol has been considered, although no person has been executed using this agent. This is largely due to European manufacturers and governments banning the export of propofol for such use.[32][33]

Recreational use

[edit]Recreational use of the drug via self-administration has been reported[34][35] but is relatively rare due to its potency and the level of monitoring required for safe use. Critically, a steep dose-response curve makes recreational use of propofol very dangerous, and deaths from self-administration continue to be reported.[36][37] The short-term effects sought via recreational use include mild euphoria, hallucinations, and disinhibition.[38][39]

Recreational use of the drug has been described among medical staff, such as anesthetists who have access to the drug.[40][41] It is reportedly more common among anesthetists on rotations with short rest periods, as usage generally produces a well-rested feeling.[42] Long-term use has been reported to result in addiction.[40][43]

Attention to the risks of off-label use of propofol increased in August 2009, after the release of the Los Angeles County coroner's report that musician Michael Jackson was killed by a mixture of propofol and the benzodiazepine drugs lorazepam, midazolam, and diazepam on 25 June 2009.[44][45][46][47] According to a 22 July 2009 search warrant affidavit unsealed by the district court of Harris County, Texas, Jackson's physician, Conrad Murray, administered 25 milligrams of propofol diluted with lidocaine shortly before Jackson's death.[45][46][48]

Manufacturing

[edit]Propofol as a commercial sterile emulsified formulation is considered difficult to manufacture.[49][50][51]

It was initially formulated in Cremophor for human use, but this original formulation was implicated in an unacceptable number of anaphylactic events. It was eventually manufactured as a 1% emulsion in soybean oil.[52] Sterile emulsions represent complex formulation, the stability of which is dependent on the interplay of many factors such as micelle size and distribution.[53][54]

Side effects

[edit]One of propofol's most common side effects is pain on injection, especially in smaller veins. This pain arises from activation of the pain receptor, TRPA1,[55] found on sensory nerves and can be mitigated by pretreatment with lidocaine.[56] Less pain is experienced when infused at a slower rate in a large vein (antecubital fossa). Patients show considerable variability in their response to propofol, at times showing profound sedation with small doses.

Additional side effects include low blood pressure related to vasodilation, transient apnea following induction doses, and cerebrovascular effects. Propofol has more pronounced hemodynamic effects relative to many intravenous anesthetic agents.[57] Reports of blood pressure drops of 30% or more are thought to be at least partially due to inhibition of sympathetic nerve activity.[58] This effect is related to the dose and rate of propofol administration. It may also be potentiated by opioid analgesics.[59]

Propofol can also cause decreased systemic vascular resistance, myocardial blood flow, and oxygen consumption, possibly through direct vasodilation.[60] There are also reports that it may cause green discoloration of the urine.[61]

Although propofol is widely used in the adult ICU setting, the side effects associated with medication seem to be more concerning in children. In the 1990s, multiple reported deaths of children in ICUs associated with propofol sedation prompted the FDA to issue a warning.[62]

As a respiratory depressant, propofol frequently produces apnea. The persistence of apnea can depend on factors such as premedication, dose administered, and rate of administration, and may sometimes persist for longer than 60 seconds.[63] Possibly as the result of depression of the central inspiratory drive, propofol may produce significant decreases in respiratory rate, minute volume, tidal volume, mean inspiratory flow rate, and functional residual capacity.[57]

Propofol administration also results in decreased cerebral blood flow, cerebral metabolic oxygen consumption, and intracranial pressure.[64] In addition, propofol may decrease intraocular pressure by as much as 50% in patients with normal intraocular pressure.[65]

A more serious but rare side effect is dystonia.[66] Mild myoclonic movements are common, as with other intravenous hypnotic agents. Propofol appears to be safe for use in porphyria, and has not been known to trigger malignant hyperpyrexia.[citation needed]

Propofol is also reported to induce priapism in some individuals,[67][68] and has been observed to suppress REM sleep and to worsen the poor sleep quality in some patients.[69]

Rare side effects include:[70]

- anxiety

- changes in vision

- cloudy urine

- coughing up blood

- delirium or hallucinations

- difficult urination

- difficulty swallowing

- dry eyes, mouth, nose, or throat

As with any other general anesthetic agent, propofol should be administered only where appropriately trained staff and facilities for monitoring are available, as well as proper airway management, a supply of supplemental oxygen, artificial ventilation, and cardiovascular resuscitation.[71]

Because of propofol's formulation (using lecithin and soybean oil), it is prone to bacterial contamination, despite the presence of the bacterial inhibitor benzyl alcohol; consequently, some hospital facilities require the IV tubing (of continuous propofol infusions) to be changed after 12 hours. This is a preventive measure against microbial growth and potential infection.[72]

Propofol infusion syndrome

[edit]A rare, but serious, side effect is propofol infusion syndrome. This potentially lethal metabolic derangement has been reported in critically ill patients after a prolonged infusion of high-dose propofol, sometimes in combination with catecholamines and/or corticosteroids.[73]

Interactions

[edit]The respiratory effects of propofol are increased if given with other respiratory depressants, including benzodiazepines.[74]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Propofol has been proposed to have several mechanisms of action,[75][76][77] both through potentiation of GABAA receptor activity and therefore acting as a GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulator, thereby slowing the channel-closing time. At high doses, propofol may be able to activate GABAA receptors in the absence of GABA, behaving as a GABAA receptor agonist as well.[78][79][80] Propofol analogs have been shown to also act as sodium channel blockers.[81][82] Some research has also suggested that the endocannabinoid system may contribute significantly to propofol's anesthetic action and to its unique properties, as endocannabinoids also play an important role in the physiologic control of sleep, pain processing and emesis.[83][84] An EEG study on patients undergoing general anesthesia with propofol found that it causes a prominent reduction in the brain's information integration capacity.[85]

Propofol is an inhibitor of the enzyme fatty acid amide hydrolase, which metabolizes the endocannabinoid anandamide (AEA). Activation of the endocannabinoid system by propofol, possibly via inhibition of AEA catabolism, generates a significant increase in the whole-brain content of AEA, contributing to the sedative properties of propofol via CB1 receptor activation.[86] This may explain the psychotomimetic and antiemetic properties of propofol. By contrast, there is a high incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting after administration of volatile anesthetics, which contribute to a significant decrease in the whole-brain content of AEA that can last up to forty minutes after induction.[84]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]

Propofol is highly protein-bound in vivo and is metabolized by conjugation in the liver.[87] The half-life of elimination of propofol has been estimated to be between 2 and 24 hours. However, its duration of clinical effect is much shorter, because propofol is rapidly distributed into peripheral tissues. When used for IV sedation, a single dose of propofol typically wears off within minutes. Onset is rapid, in as little as 15–30 seconds.[5] Propofol is versatile; the drug can be given for short or prolonged sedation, as well as for general anesthesia. Its use is not associated with nausea as is often seen with opioid medications. These characteristics of rapid onset and recovery along with its amnestic effects[88] have led to its widespread use for sedation and anesthesia.

History

[edit]John B. Glen, a veterinarian and researcher at Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI), spent thirteen years developing propofol, an effort for which he was awarded the 2018 Lasker Award for clinical research.

Originally developed as ICI 35868, propofol was chosen after extensive evaluation and structure–activity relationship studies of the anesthetic potencies and pharmacokinetic profiles of a series of ortho-alkylated phenols.[89]

First identified as a drug candidate in 1973, propofol entered clinical trials in 1977, using a form solubilized in cremophor EL.[90] However, due to anaphylactic reactions to cremophor, this formulation was withdrawn from the market and subsequently reformulated as an emulsion of a soya oil and propofol mixture in water. The emulsified formulation was relaunched in 1986 by ICI (whose pharmaceutical division later became a constituent of AstraZeneca) under the brand name Diprivan. The preparation contains 1% propofol, 10% soybean oil, and 1.2% purified egg phospholipid as an emulsifier, with 2.25% glycerol as a tonicity-adjusting agent, and sodium hydroxide to adjust the pH. Diprivan contains EDTA, a common chelation agent, that also acts alone (bacteriostatically against some bacteria) and synergistically with some other antimicrobial agents. Newer generic formulations contain sodium metabisulfite as an antioxidant and benzyl alcohol as an antimicrobial agent. Propofol emulsion is an opaque white fluid due to the scattering of light from the emulsified micelle formulation.

Developments

[edit]A water-soluble prodrug form, fospropofol, has been developed and tested with positive results. Fospropofol is rapidly broken down by the enzyme alkaline phosphatase to form propofol. Marketed as Lusedra, this formulation may not produce the pain at the injection site that often occurs with the conventional form of the drug. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the product in 2008.[91]

By incorporation of an azobenzene unit, a photoswitchable version of propofol (AP2) was developed in 2012 that allows for optical control of GABAA receptors with light.[92] In 2013, a propofol binding site on mammalian GABAA receptors has been identified by photolabeling using a diazirine derivative.[93] Additionally, it was shown that the hyaluronan polymer present in the synovia can be protected from free-radical depolymerization by propofol.[94]

Ciprofol is another derivative of propofol that is 4–6 times more potent than propofol. As of 2022[update] it is undergoing Phase III trials. Ciprofol appears to have a lower incidence of injection site pain and respiratory depression than propofol.[95]

Propofol has also been studied for treatment resistant depression.[96]

Veterinary uses

[edit]In November 2024, the US Food and Drug Administration approved PropofolVet Multidose, the first generic propofol injectable emulsion for dogs.[97][98] PropofolVet Multidose is approved for use as an injectable anesthetic in dogs.[97]

PropofolVet Multidose contains the same active ingredient (propofol injectable emulsion) as the approved brand name drug product, PropoFlo 28, which was first approved on 4 February 2011.[97] In addition, the FDA determined that PropofolVet Multidose contains no inactive ingredients that may significantly affect the bioavailability of the active ingredient.[97] PropofolVet Multidose is sponsored by Parnell Technologies Pty. Ltd. based in New South Wales, Australia.[97]

References

[edit]- ^ "Propofol". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ Ruffle JK (November 2014). "Molecular neurobiology of addiction: what's all the (Δ)FosB about?". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 40 (6): 428–437. doi:10.3109/00952990.2014.933840. PMID 25083822.

Propofol is a general anesthetic, however its abuse for recreational purpose has been documented (120). Using control drugs implicated in both ΔFosB induction and addiction (ethanol and nicotine), similar ΔFosB expression was apparent when propofol was given to rats. Moreover, this cascade was shown to act via the dopamine D1 receptor in the NAc, suggesting that propofol has abuse potential (119)

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Diprivan- propofol injection, emulsion". DailyMed. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Propofol". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2017.

- ^ Arcario MJ, Mayne CG, Tajkhorshid E (October 2014). "Atomistic models of general anesthetics for use in in silico biological studies". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 118 (42). American Chemical Society (ACS): 12075–12086. Bibcode:2014JPCB..11812075A. doi:10.1021/jp502716m. PMC 4207551. PMID 25303275.

- ^ "Propofol". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ "Making Stable, Sterile Propofol". www.microfluidics-mpt.com. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ "Propofol". go.drugbank.com. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ Glen JB (September 2018). "The Discovery and Development of Propofol Anesthesia: The 2018 Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award". JAMA. 320 (12): 1235–1236. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.12756. PMID 30208399.

- ^ Glen JB (July 2019). "Try, try, and try again: personal reflections on the development of propofol". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 123 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2019.02.031. PMID 30982566.

- ^ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ "Discovery and development of propofol, a widely used anesthetic". The Lasker Foundation. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

Propofol is used today to initiate anesthesia in nearly 100% of general anesthesia cases worldwide.

- ^ Gale T, Leslie K, Kluger M (December 2001). "Propofol anaesthesia via target controlled infusion or manually controlled infusion: effects on the bispectral index as a measure of anaesthetic depth". Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 29 (6): 579–584. doi:10.1177/0310057X0102900602. PMID 11771598.

- ^ a b Lewis SR, Schofield-Robinson OJ, Alderson P, Smith AF (January 2018). "Propofol for the promotion of sleep in adults in the intensive care unit". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1) CD012454. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012454.pub2. PMC 6353271. PMID 29308828.

- ^ a b c Cox CE, Reed SD, Govert JA, Rodgers JE, Campbell-Bright S, Kress JP, et al. (March 2008). "Economic evaluation of propofol and lorazepam for critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation". Critical Care Medicine. 36 (3): 706–714. doi:10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181544248. PMC 2763279. PMID 18176312.

- ^ a b Isert PR, Lee D, Naidoo D, Carasso ML, Kennedy RA (June 1996). "Compatibility of propofol, fentanyl, and vecuronium mixtures designed for potential use in anesthesia and patient transport". Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 8 (4): 329–336. doi:10.1016/0952-8180(96)00043-8. PMID 8695138.

- ^ Gavel G, Walker RW (April 2014). "Laryngospasm in anaesthesia". Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 14 (2): 47–51. doi:10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkt031.

- ^ McQuaid KR, Laine L (May 2008). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials of moderate sedation for routine endoscopic procedures". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 67 (6): 910–923. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2007.12.046. PMID 18440381.

- ^ Canadian National Formulary 2010

- ^ Shannon MT, Wilson BA, Stang CL (1999). Appleton & Lange's 1999 drug guide. Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange. ISBN 978-0-8385-0371-3.

- ^ Numorphan® (oxymorphone) package insert (English), Endo 2009

- ^ Machata AM, Willschke H, Kabon B, Kettner SC, Marhofer P (August 2008). "Propofol-based sedation regimen for infants and children undergoing ambulatory magnetic resonance imaging". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 101 (2): 239–243. doi:10.1093/bja/aen153. PMID 18534971.

- ^ Yan JW, McLeod SL, Iansavitchene A (September 2015). "Ketamine-Propofol Versus Propofol Alone for Procedural Sedation in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Academic Emergency Medicine. 22 (9): 1003–1013. doi:10.1111/acem.12737. PMID 26292077.

- ^ "Propofol-Lipuro 1% (propofol) Injectable emulsion for infusion – 1,000 mg in 100 ml (10 mg /ml): Fact Sheet for health Care Providers" (PDF). Bbraunusa.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Letter RE: Emergency Use Authorization 096". Fda.gov. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Fact Sheet for Health Care Providers: Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of Propofol-Lipuro 1% Injectable Emulsion for Infusion". Fda.gov. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Emergency Use Authorization". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ "Emergency Use Authorization--Archived Information". FDA. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023.

- ^ Rao VR, Lowenstein DH (2022). "Seizures and epilepsy.". In Loscalzo J, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J (eds.). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (21st ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-1-264-26851-1.

- ^ Reggler J, Daws T (May 2017). "Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD): Protocols and Procedures Handbook" (PDF). Divisions of Family Practice (2nd ed.). Comox Valley, British Columbia.

- ^ Kim E, Levy RJ (February 2020). "The role of anaesthesiologists in lethal injection: a call to action". Lancet. 395 (10225): 749–754. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32986-1. PMC 7416913. PMID 32014115.

- ^ "Lethal injection: Secretive US states resort to untested drugs". BBC News. 15 November 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ Riezzo I, Centini F, Neri M, Rossi G, Spanoudaki E, Turillazzi E, et al. (April 2009). "Brugada-like EKG pattern and myocardial effects in a chronic propofol abuser". Clinical Toxicology. 47 (4): 358–363. doi:10.1080/15563650902887842. hdl:11392/2357145. PMID 19514884.

- ^ Belluck P (6 August 2009). "With High-Profile Death, Focus on High-Risk Drug". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- ^ Iwersen-Bergmann S, Rösner P, Kühnau HC, Junge M, Schmoldt A (2001). "Death after excessive propofol abuse". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 114 (4–5): 248–251. doi:10.1007/s004149900129. PMID 11355404.

- ^ Kranioti EF, Mavroforou A, Mylonakis P, Michalodimitrakis M (March 2007). "Lethal self administration of propofol (Diprivan). A case report and review of the literature". Forensic Science International. 167 (1): 56–58. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.12.027. PMID 16431058.

- ^ Sweetman SC, ed. (2005). Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (34th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 1305–1307. ISBN 978-0-85369-550-9.

- ^ Baudoin Z (2000). "General anesthetics and anesthetic gases.". In Dukes MN, Aronson JK (eds.). Meyler's Side Effects of Drugs (14th ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-444-50093-9.

- ^ a b Roussin A, Montastruc JL, Lapeyre-Mestre M (October 2007). "Pharmacological and clinical evidences on the potential for abuse and dependence of propofol: a review of the literature". Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology. 21 (5): 459–466. doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.2007.00497.x. PMID 17868199.

- ^ Ward CF (2008). "Propofol: dancing with a "White Rabbit."" (PDF). California Society Anesthesiology Bulletin. 57 (Spring): 61–63. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ Charatan F (September 2009). "Concerns mount over misuse of anaesthetic propofol among US health professionals". BMJ. 339 b3673. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3673. PMID 19737827.

- ^ Bonnet U, Harkener J, Scherbaum N (June 2008). "A case report of propofol dependence in a physician". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 40 (2): 215–217. doi:10.1080/02791072.2008.10400634. PMID 18720673.

- ^ Moore S (28 August 2009). "Jackson's Death Ruled a Homicide". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013.

- ^ a b Surdin A (25 August 2009). "Coroner Attributes Michael Jackson's Death to Propofol". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ a b Itzkoff D (24 August 2009). "Coroner's Findings in Jackson Death Revealed". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 June 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "Jackson's Death: How Dangerous Is Propofol?". Time. 25 August 2009. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "Michael Jackson search warrant". Scribd. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Rooimans T, Damen M, Markesteijn CM, Schuurmans CC, de Zoete NH, van Hasselt PM, et al. (June 2023). "Development of a compounded propofol nanoemulsion using multiple non-invasive process analytical technologies". International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 640 122960. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2023.122960. PMC 10101488. PMID 37061210.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Zorrilla-Vaca A, Arevalo JJ, Escandón-Vargas K, Soltanifar D, Mirski MA (June 2016). "Infectious Disease Risk Associated with Contaminated Propofol Anesthesia, 1989-2014(1)". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (6): 981–992. doi:10.3201/eid2206.150376. PMC 4880094. PMID 27192163.

- ^ WO 2014033751A2, Pramanick S, Gurjar S, Mehta SS, "Pharmaceutical composition of propofol", issued 6 March 2014, assigned to Emcure Pharmaceuticals Limited

- ^ Glen JB (July 2019). "Try, try, and try again: personal reflections on the development of propofol". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 123 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2019.02.031. PMID 30982566.

- ^ "Hospira recalls lot of Propofol Injectable Emulsion". European Pharmaceutical Review. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ "Understanding Emulsion Formulation | Ascendia Pharmaceuticals". ascendiapharma.com. 8 November 2021. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ Matta JA, Cornett PM, Miyares RL, Abe K, Sahibzada N, Ahern GP (June 2008). "General anesthetics activate a nociceptive ion channel to enhance pain and inflammation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (25): 8784–8789. doi:10.1073/pnas.0711038105. PMC 2438393. PMID 18574153.

- ^ "Propofol Drug Information, Professional". m drugs.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2007. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- ^ a b Sebel PS, Lowdon JD (August 1989). "Propofol: a new intravenous anesthetic". Anesthesiology. 71 (2): 260–277. doi:10.1097/00000542-198908000-00015. PMID 2667401.

- ^ Robinson BJ, Ebert TJ, O'Brien TJ, Colinco MD, Muzi M (January 1997). "Mechanisms whereby propofol mediates peripheral vasodilation in humans. Sympathoinhibition or direct vascular relaxation?". Anesthesiology. 86 (1): 64–72. doi:10.1097/00000542-199701000-00010. PMID 9009941.

- ^ "New awakening in anaesthesia—at a price". Lancet. 329 (8548): 1469–70. 1987. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92214-8.

- ^ Larijani GE, Gratz I, Afshar M, Jacobi AG (October 1989). "Clinical pharmacology of propofol: an intravenous anesthetic agent". DICP. 23 (10): 743–749. doi:10.1177/106002808902301001. PMID 2683416.

- ^ Lee JS, Jang HS, Park BJ (August 2013). "Green discoloration of urine after propofol infusion". Korean Journal of Anesthesiology. 65 (2): 177–179. doi:10.4097/kjae.2013.65.2.177. PMC 3766788. PMID 24024005.

- ^ Parke TJ, Stevens JE, Rice AS, Greenaway CL, Bray RJ, Smith PJ, et al. (September 1992). "Metabolic acidosis and fatal myocardial failure after propofol infusion in children: five case reports". BMJ. 305 (6854): 613–616. doi:10.1136/bmj.305.6854.613. PMC 1883365. PMID 1393073.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Langley MS, Heel RC (April 1988). "Propofol. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and use as an intravenous anaesthetic". Drugs. 35 (4): 334–372. doi:10.2165/00003495-198835040-00002. PMID 3292208.

- ^ Bailey JM, Mora CT, Shafer SL (June 1996). "Pharmacokinetics of propofol in adult patients undergoing coronary revascularization. The Multicenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group". Anesthesiology. 84 (6): 1288–1297. doi:10.1097/00000542-199606000-00003. PMID 8669668.

- ^ Reilly CS, Nimmo WS (July 1987). "New intravenous anaesthetics and neuromuscular blocking drugs. A review of their properties and clinical use". Drugs. 34 (1): 98–135. doi:10.2165/00003495-198734010-00004. PMID 3308413.

- ^ Schramm BM, Orser BA (May 2002). "Dystonic reaction to propofol attenuated by benztropine (cogentin)". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 94 (5): 1237–40, table of contents. doi:10.1097/00000539-200205000-00034. PMID 11973196.

- ^ Vesta KS, Martina SD, Kozlowski EA (May 2006). "Propofol-induced priapism, a case confirmed with rechallenge". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 40 (5): 980–982. doi:10.1345/aph.1G555. PMID 16638914.

- ^ Fuentes EJ, Garcia S, Garrido M, Lorenzo C, Iglesias JM, Sola JE (July 2009). "Successful treatment of propofol-induced priapism with distal glans to corporal cavernosal shunt". Urology. 74 (1): 113–115. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2008.12.066. PMID 19371930.

- ^ Kondili E, Alexopoulou C, Xirouchaki N, Georgopoulos D (October 2012). "Effects of propofol on sleep quality in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a physiological study". Intensive Care Medicine. 38 (10): 1640–1646. doi:10.1007/s00134-012-2623-z. PMID 22752356.

- ^ "Propofol (Intravenous Route) Side Effects - Mayo Clinic". Mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "AstraZeneca – United States Home Page" (PDF). .astrazeneca-us.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^ Kim TE, Shankel T, Reibling ET, Paik J, Wright D, Buckman M, et al. (1 January 2017). "Healthcare students interprofessional critical event/disaster response course". American Journal of Disaster Medicine. 12 (1): 11–26. doi:10.5055/ajdm.2017.0254. PMID 28822211.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Vasile B, Rasulo F, Candiani A, Latronico N (September 2003). "The pathophysiology of propofol infusion syndrome: a simple name for a complex syndrome". Intensive Care Medicine. 29 (9): 1417–1425. doi:10.1007/s00134-003-1905-x. PMID 12904852.

- ^ Doheny K, Chang L, Vila Jr H (24 August 2009). "Propofol Linked to Michael Jackson's Death". WebMD. Archived from the original on 28 August 2009. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- ^ Trapani G, Altomare C, Liso G, Sanna E, Biggio G (February 2000). "Propofol in anesthesia. Mechanism of action, structure-activity relationships, and drug delivery". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 7 (2): 249–271. doi:10.2174/0929867003375335. PMID 10637364.

- ^ Kotani Y, Shimazawa M, Yoshimura S, Iwama T, Hara H (Summer 2008). "The experimental and clinical pharmacology of propofol, an anesthetic agent with neuroprotective properties". CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 14 (2): 95–106. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2008.00043.x. PMC 6494023. PMID 18482023.

- ^ Vanlersberghe C, Camu F (2008). "Propofol". Modern Anesthetics. Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology. Vol. 182. pp. 227–52. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-74806-9_11. ISBN 978-3-540-72813-9. PMID 18175094.

- ^ Trapani G, Latrofa A, Franco M, Altomare C, Sanna E, Usala M, et al. (May 1998). "Propofol analogues. Synthesis, relationships between structure and affinity at GABAA receptor in rat brain, and differential electrophysiological profile at recombinant human GABAA receptors". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 41 (11): 1846–1854. doi:10.1021/jm970681h. PMID 9599235.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Krasowski MD, Jenkins A, Flood P, Kung AY, Hopfinger AJ, Harrison NL (April 2001). "General anesthetic potencies of a series of propofol analogs correlate with potency for potentiation of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) current at the GABA(A) receptor but not with lipid solubility". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 297 (1): 338–351. doi:10.1016/S0022-3565(24)29544-6. PMID 11259561.

- ^ Krasowski MD, Hong X, Hopfinger AJ, Harrison NL (July 2002). "4D-QSAR analysis of a set of propofol analogues: mapping binding sites for an anesthetic phenol on the GABA(A) receptor". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 45 (15): 3210–3221. doi:10.1021/jm010461a. PMC 2864546. PMID 12109905.

- ^ Haeseler G, Leuwer M (March 2003). "High-affinity block of voltage-operated rat IIA neuronal sodium channels by 2,6 di-tert-butylphenol, a propofol analogue". European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 20 (3): 220–224. doi:10.1017/s0265021503000371. PMID 12650493.

- ^ Haeseler G, Karst M, Foadi N, Gudehus S, Roeder A, Hecker H, et al. (September 2008). "High-affinity blockade of voltage-operated skeletal muscle and neuronal sodium channels by halogenated propofol analogues". British Journal of Pharmacology. 155 (2): 265–275. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.255. PMC 2538694. PMID 18574460.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Fowler CJ (February 2004). "Possible involvement of the endocannabinoid system in the actions of three clinically used drugs". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 25 (2): 59–61. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2003.12.001. PMID 15106622.

- ^ a b Schelling G (2006). "Effects of General Anesthesia on Anandamide Blood Levels in Humans". Anesthesiology. 104 (2): 273–277. doi:10.1097/00000542-200602000-00012. PMID 16436846.

- ^ Lee U, Mashour GA, Kim S, Noh GJ, Choi BM (March 2009). "Propofol induction reduces the capacity for neural information integration: implications for the mechanism of consciousness and general anesthesia". Consciousness and Cognition. 18 (1): 56–64. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2008.10.005. PMID 19054696.

- ^ Patel S, Wohlfeil ER, Rademacher DJ, Carrier EJ, Perry LJ, Kundu A, et al. (July 2003). "The general anesthetic propofol increases brain N-arachidonylethanolamine (anandamide) content and inhibits fatty acid amide hydrolase". British Journal of Pharmacology. 139 (5): 1005–1013. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0705334. PMC 1573928. PMID 12839875.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Favetta P, Degoute CS, Perdrix JP, Dufresne C, Boulieu R, Guitton J (May 2002). "Propofol metabolites in man following propofol induction and maintenance". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 88 (5): 653–658. doi:10.1093/bja/88.5.653. PMID 12067002.

- ^ Veselis RA, Reinsel RA, Feshchenko VA, Wroński M (October 1997). "The comparative amnestic effects of midazolam, propofol, thiopental, and fentanyl at equisedative concentrations". Anesthesiology. 87 (4): 749–764. doi:10.1097/00000542-199710000-00007. PMID 9357875.

- ^ James R, Glen JB (December 1980). "Synthesis, biological evaluation, and preliminary structure-activity considerations of a series of alkylphenols as intravenous anesthetic agents". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 23 (12): 1350–1357. doi:10.1021/jm00186a013. PMID 7452689.

- ^ Lasker Foundation. "Discovery and development of propofol, a widely used anesthetic". The Lasker Foundation. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ^ Stein M, Middendorp SJ, Carta V, Pejo E, Raines DE, Forman SA, et al. (October 2012). "Azo-propofols: photochromic potentiators of GABA(A) receptors". Angewandte Chemie. 51 (42): 10500–10504. Bibcode:2012ACIE...5110500S. doi:10.1002/anie.201205475. PMC 3606271. PMID 22968919.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Yip GM, Chen ZW, Edge CJ, Smith EH, Dickinson R, Hohenester E, et al. (November 2013). "A propofol binding site on mammalian GABAA receptors identified by photolabeling". Nature Chemical Biology. 9 (11): 715–720. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1340. PMC 3951778. PMID 24056400.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Kvam C, Granese D, Flaibani A, Pollesello P, Paoletti S (June 1993). "Hyaluronan can be protected from free-radical depolymerisation by 2,6-diisopropylphenol, a novel radical scavenger". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 193 (3): 927–933. Bibcode:1993BBRC..193..927K. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1993.1714. PMID 8391811.

- ^ Chen BZ, Yin XY, Jiang LH, Liu JH, Shi YY, Yuan BY (August 2022). "The efficacy and safety of ciprofol use for the induction of general anesthesia in patients undergoing gynecological surgery: a prospective randomized controlled study". BMC Anesthesiology. 22 (1) 245. doi:10.1186/s12871-022-01782-7. PMC 9347095. PMID 35922771.

- ^ Wu G, Xu H (October 2023). "A synopsis of multitarget therapeutic effects of anesthetics on depression". European Journal of Pharmacology. 957 176032. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2023.176032. PMID 37660970.

- ^ a b c d e "FDA Approves Generic Propofol Injectable Emulsion for Dogs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 18 November 2024. Archived from the original on 18 November 2024. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ "Recent Animal Drug Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2 December 2024. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

External links

[edit]- GB patent 1472793, John B. Glen; Roger James & Bob-James Munroe, "Pharmaceutical Compositions", published 4 May 1977, assigned to Imperial Chemical Industries Ltd Archived 5 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

Propofol

View on GrokipediaMedical Applications

Induction and Maintenance of General Anesthesia

Propofol, administered intravenously as a lipid emulsion, is the most common intravenous hypnotic agent for the induction and maintenance of general anesthesia, particularly in total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) for outpatient settings, often combined with short-acting opioids, due to its rapid onset (30–60 seconds) and short duration of action.[8] For induction in unpremedicated adults aged 55 years or younger, a typical bolus dose ranges from 2 to 2.5 mg/kg, while elderly, debilitated, or American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class III/IV patients require 1 to 1.5 mg/kg to achieve loss of consciousness within 30 to 60 seconds.[9] In children, doses are increased by approximately 50% to account for higher distribution volumes and faster clearance.[9] Maintenance follows via continuous infusion at 100 to 200 mcg/kg/min, titrated to clinical effect, often supplemented with opioids or neuromuscular blockers for balanced anesthesia.[8] The pharmacokinetics of propofol facilitate its suitability for these applications, featuring rapid redistribution from the brain to peripheral tissues, resulting in a brief duration of approximately 5 to 10 minutes after a single induction bolus.[2] Hepatic metabolism via cytochrome P450 and extrahepatic conjugation yields inactive metabolites, with clearance rates of 23 to 50 mL/kg/min in adults, enabling predictable recovery upon discontinuation.[4] This profile contrasts with longer-acting agents, allowing for swift emergence and reduced residual effects, though prolonged infusions necessitate monitoring for accumulation in fat compartments.[4] Propofol's pharmacodynamic effects include dose-dependent central nervous system depression primarily through potentiation of GABA_A receptors, leading to profound hypnosis and amnesia without significant analgesia, along with dose-dependent respiratory depression and hypotension via vasodilation and myocardial depression.[10][2] Advantages in general anesthesia include smooth induction, minimal excitatory phenomena, antiemetic properties that lower postoperative nausea and vomiting incidence compared to inhalational agents, and fast recovery (5–15 minutes to orientation) with clear-headed emergence.[8] However, induction often provokes injection-site pain in up to 30% of cases, mitigated by co-administration with lidocaine, and both phases carry risks of transient apnea and hypotension, requiring vigilant airway management.[2] These hemodynamic effects are more pronounced in hypovolemic or cardiovascularly compromised patients; propofol infusion syndrome is rare and less relevant in outpatient use.[2]Procedural Sedation

Propofol is utilized for procedural sedation to achieve a state of conscious or deep sedation, enabling patients to tolerate uncomfortable or painful short-duration procedures such as endoscopy, colonoscopy, fracture reduction, abscess incision and drainage, or laceration repair, while maintaining cardiorespiratory function.[11] Its appeal stems from a rapid onset of action within 30-60 seconds and short duration of effect, typically 3-10 minutes after bolus administration, facilitating swift recovery and minimizing disruption in high-volume settings like emergency departments.31576-2/fulltext) [12] Standard dosing for adults begins with an initial intravenous bolus of 0.5-1 mg/kg over 1-2 minutes, titrated to effect, followed by supplemental boluses of 0.25-0.5 mg/kg every 2-3 minutes as needed to maintain sedation depth.[11] [13] For pediatric patients, initial doses range from 1-2 mg/kg, with maintenance boluses of 0.5-1 mg/kg.[13] Continuous infusions, at rates of 100-150 mcg/kg/min in adults or up to 250 mcg/kg/min in children, may be employed for procedures requiring sustained sedation, reducing peak-trough fluctuations associated with repeated boluses.[13] Propofol lacks analgesic properties, so it is often combined with opioids like fentanyl (1-2 mcg/kg) or ketamine for painful interventions, though this increases risks of compounded respiratory depression.[14] The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) 2018 clinical practice guideline endorses propofol for emergency department procedural sedation in appropriately selected patients, based on evidence from prospective studies demonstrating high success rates (over 95%) and low adverse event incidence when administered by emergency physicians with airway management training.31576-2/fulltext) [12] Monitoring protocols mandate continuous pulse oximetry, capnography, blood pressure assessment every 5 minutes, and availability of reversal agents and resuscitation equipment, with personnel solely dedicated to sedation oversight separate from procedure performance.31576-2/fulltext) [15] Safety data from emergency department cohorts indicate transient adverse events like hypoxia (oxygen saturation <90%) in 5-10% of cases and hypotension (systolic blood pressure drop >20%) in 5-15%, most resolving with supportive interventions such as supplemental oxygen or brief pauses in dosing, though rare serious events like apnea or aspiration occur in <1%.[12] 02686-2/fulltext) The American Society of Anesthesiologists maintains that propofol for sedation should be administered exclusively by anesthesia-trained providers not involved in the procedure, citing its narrow therapeutic window and potential for unintended general anesthesia.[15] In contrast, emergency medicine literature reports comparable safety profiles to anesthesiology-led sedation when protocols are followed, with recovery times under 15 minutes in most adults.[12] 00256-9/fulltext) Contraindications include known hypersensitivity, severe hemodynamic instability, or anticipated difficult airway management.[11]Intensive Care Unit Sedation

Propofol serves as a short-acting intravenous sedative agent for maintaining sedation in intensive care unit (ICU) patients, particularly those on mechanical ventilation, where it facilitates tolerance of endotracheal intubation and invasive monitoring. Its rapid onset (within 30-60 seconds) and short elimination half-life (approximately 2-24 hours, dose-dependent) enable precise titration to achieve targeted sedation levels, such as those measured by the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS), and support daily sedation interruptions for neurological evaluation and ventilator weaning trials.[9][2] The Society of Critical Care Medicine's (SCCM) 2018 Pain, Agitation/sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption (PADIS) guidelines conditionally recommend propofol or dexmedetomidine over benzodiazepines (e.g., midazolam) for continuous sedation in mechanically ventilated adults, based on evidence showing reduced delirium incidence (odds ratio 0.56 for non-benzodiazepines) and shorter mechanical ventilation duration (mean difference -1.8 days).[16] This preference stems from propofol's GABA_A receptor agonism, which provides amnesia and hypnosis without the cumulative effects of benzodiazepines. A 2025 SCCM focused update further conditionally recommends dexmedetomidine over propofol for scenarios emphasizing light sedation, citing lower delirium rates (18% vs. 25%) and better preservation of arousability in adult ICU patients.[17][18] For ICU administration, sedation typically initiates with a propofol infusion at 5 mcg/kg/min IV for at least 5 minutes, followed by titration in 5-10 mcg/kg/min increments every 5-10 minutes to clinical effect, with maintenance rates commonly ranging from 20-75 mcg/kg/min (1.2-4.5 mg/kg/hour).[19][20] Higher rates (up to 50 mcg/kg/min) may be required for deeper sedation but increase risks; guidelines advise limiting continuous infusions to under 48 hours and avoiding rates exceeding 4-5 mg/kg/hour prolonged to prevent complications like hypertriglyceridemia from the lipid emulsion vehicle (1 kcal/mL).[21][22] Hemodynamic instability, including hypotension (incidence 20-50% at higher doses due to vasodilation and myocardial depression), necessitates caution in patients with cardiovascular compromise, often requiring vasopressor support or alternative agents.[2] Propofol's antiemetic properties and lack of active metabolites make it suitable for short-term use in stable patients, but routine monitoring of triglycerides, lactate, and acid-base status is essential.[23] In pediatric ICU settings, infusions are restricted to <4 mg/kg/hour for <48 hours to minimize risks.[22] Overall, propofol's role has shifted toward adjunctive or brief applications amid evidence favoring non-GABAergic sedatives for prolonged ICU stays.[24]Treatment of Refractory Status Epilepticus

Propofol is employed as a third-line continuous intravenous anesthetic agent in the management of refractory status epilepticus (RSE), defined as seizure activity persisting despite treatment with adequate doses of a benzodiazepine and one or more second-line antiepileptic drugs such as phenytoin or levetiracetam.[25] In intensive care settings, it is administered under continuous electroencephalographic (cEEG) monitoring to achieve seizure suppression, typically targeting EEG burst suppression patterns.[26] The standard loading regimen involves 1-2 mg/kg intravenous boluses every 3-5 minutes until seizures cease, followed by an infusion starting at 2 mg/kg/hour and titrated up to 10 mg/kg/hour or higher as needed, with maintenance requiring hemodynamic support due to risks of hypotension.[25] [27] Evidence for propofol's efficacy in RSE derives primarily from observational studies and case series, lacking large randomized controlled trials; a systematic review of 10 studies involving 681 patients found seizure cessation rates of approximately 70-80% with propofol, comparable to barbiturates, though with higher rates of treatment failure upon weaning (odds ratio 2.2 favoring barbiturates).[28] In pediatric cohorts, propofol has demonstrated rapid termination of refractory seizures, with one study reporting effectiveness in 80% of cases when used before barbiturates like thiopental.[29] [30] Advantages include its rapid onset of action (within minutes), short context-sensitive half-life facilitating quick recovery and titration, and anticonvulsant properties via enhancement of GABA_A receptor-mediated inhibition.[26] However, breakthrough seizures occur frequently during weaning, necessitating multimodal therapy or alternatives like midazolam or ketamine.[31] Safety concerns are significant, particularly the risk of propofol infusion syndrome (PRIS), a potentially fatal condition involving metabolic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, cardiac arrhythmias, and renal failure, associated with infusions exceeding 4 mg/kg/hour for over 48 hours or cumulative doses above 67 mg/kg in adults.[32] [33] Non-randomized data indicate PRIS incidence up to 1-2% in RSE treatment, with mortality exceeding 50% in affected cases, prompting guidelines to limit propofol to short-term use (<48 hours) and recommend against routine application without cEEG and multidisciplinary oversight.[32] [34] Other adverse effects include profound hypotension requiring vasopressors in up to 60% of patients, hypertriglyceridemia from the lipid emulsion vehicle, and green urine discoloration, underscoring the need for lipid monitoring and alternative agents in prolonged RSE or super-refractory cases.[28] [35] Neurocritical Care Society and Emergency Neurological Life Support guidelines classify propofol as a Class IIb recommendation (may be considered) for RSE, favoring midazolam as first-choice anesthetic due to lower PRIS risk, with propofol reserved for scenarios requiring faster recovery or when barbiturates are contraindicated.[36] [34] International expert surveys reveal variable adoption, with propofol preferred by adult neurologists over barbiturates for its titratability, though pediatric intensivists often prioritize benzodiazepine infusions.[37] Overall, while propofol controls acute RSE effectively in select patients, its use demands vigilant monitoring to mitigate life-threatening complications, with evidence gaps highlighting the need for randomized trials to refine protocols.[32][28]Other Approved Indications

Propofol is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for combined sedation and regional anesthesia in adult patients, enabling its use alongside local or regional anesthetic blocks to support surgical interventions while minimizing the need for deeper general anesthesia.[38] This indication, specific to adults, facilitates procedures such as orthopedic surgeries or peripheral nerve blocks by providing titratable sedation that preserves respiratory drive and hemodynamic stability when administered judiciously.[38] Clinical guidelines emphasize monitoring for respiratory depression, as propofol's rapid onset and short duration allow for precise control but require vigilant oversight by trained personnel.[19] In pediatric populations, while primary indications focus on general anesthesia induction for children aged 3 years and older and maintenance from 2 months onward, propofol's approval does not extend to combined regional techniques in this group, limiting its "other" applications to the delineated adult contexts.[38] No additional FDA-approved indications beyond anesthesia induction/maintenance, procedural/MAC sedation, ICU ventilation support, and this regional combination exist as of the 2017 label revision.[38]Controversial and Off-Label Uses

Assisted Dying and Euthanasia

Propofol serves as an intravenous anesthetic in certain clinician-administered euthanasia and medical assistance in dying (MAID) protocols where physician intervention is permitted, such as in Canada, Belgium, and the Netherlands, to induce rapid unconsciousness before lethal agents like neuromuscular blockers are given.[39] In these procedures, it is typically administered after premedication with an anxiolytic such as midazolam (to reduce anxiety) and lidocaine (to minimize injection pain), ensuring the patient experiences no awareness during the process.[40] High doses, often 1000–2000 mg, are employed to achieve deep coma within seconds via central nervous system depression and respiratory arrest, though in frail individuals, propofol alone may precipitate cardiac arrest without additional drugs.[41][42] In Canada, propofol features in over 98% of intravenous MAID cases, forming part of a standard sequence that includes rocuronium bromide afterward to induce paralysis and hasten death by diaphragmatic failure, with median time to death reported at 8.7 minutes across thousands of provisions.[39] Protocols specify preparing 1000 mg (e.g., two 50 mL syringes of 10 mg/mL solution) for administration, though higher doses or combinations can extend time to death due to potential technical issues or variable patient factors like body mass.[43][44] Complications are rare but include prolonged survival if vascular access fails or if propofol dosing is suboptimal, underscoring the need for trained personnel.[39] Belgium has seen rising propofol use in euthanasia since the law's 2002 enactment, persisting into 2024 despite thiopental's reavailability, with physicians attributing this to logistical advantages like easier procurement and administration over barbiturates.[45] In 2024, euthanasia comprised 3.6% of all Belgian deaths (up from 3.1% in 2023), often involving propofol or thiopental for induction followed by relaxants, though exact propofol prevalence in reported cases remains unspecified in annual reviews.[46] Dutch guidelines prioritize barbiturates for euthanasia but permit propofol alternatives in practice, reflecting its efficacy in ensuring painless induction amid shortages of preferred agents.[47] Propofol's role is limited in self-administered assisted dying due to the need for intravenous delivery, favoring oral barbiturates elsewhere, but its adoption in clinician-led euthanasia highlights trade-offs: rapid onset minimizes distress yet risks infusion syndrome or delayed lethality when paired with paralytics, prompting ongoing protocol refinements based on case data.[39][44]Lethal Injection in Capital Punishment

Missouri became the first U.S. state to adopt propofol as the sole agent in a one-drug lethal injection protocol on April 4, 2012, replacing a prior three-drug combination amid national shortages of traditional execution drugs like sodium thiopental.[48] The protocol specified administering 5,000 milligrams of propofol intravenously over approximately two minutes to induce unconsciousness followed by fatal respiratory and cardiac depression, though this method remained untested in executions and drew pharmacological scrutiny for potential variability in onset and efficacy compared to barbiturates.[49] No state has executed an inmate using propofol, as implementation faced immediate barriers including manufacturer restrictions and international supply pressures.[50] AstraZeneca, the primary producer of pharmaceutical-grade propofol, announced on September 27, 2012, that it would not supply the drug for capital punishment, citing ethical opposition and risks to its global distribution network, particularly from the European Union, which produces most of the world's supply.[51] This stance aligned with broader pharmaceutical industry trends, as seen in Pfizer's 2021 policy explicitly prohibiting the use of its products, including propofol formulations, in lethal injections due to reputational and legal liabilities.[52] Critics, including medical ethicists, argued that repurposing a widely used anesthetic—administered in up to 50 million U.S. procedures annually—could exacerbate shortages and endanger patients by prompting export restrictions, a concern realized when the EU threatened to halt shipments to Missouri in October 2013.[49] Missouri ultimately returned a propofol shipment to its distributor on October 9, 2013, and Governor Jay Nixon stayed the scheduled execution of Joseph Franklin on October 11, 2013, citing risks to the state's drug supply for medical use.[53][54] Legal challenges further stalled adoption, with inmates contesting the protocol's constitutionality under the Eighth Amendment for lacking established humaneness; Missouri's Supreme Court approved its use for two October 2013 dates but deferred amid supply issues.[55] Proponents, including some Department of Corrections officials, viewed propofol as a viable alternative due to its rapid sedative effects and availability in compounded forms, potentially reducing risks of prolonged suffering associated with multi-drug regimens.[56] However, opponents highlighted empirical uncertainties: animal studies and overdose cases indicate propofol can cause death via apnea and hypotension, but execution doses risked incomplete anesthesia or paradoxical excitation, potentially violating standards against cruel punishment without veterinary or clinical precedents for lethal intent.[57] By 2016, Missouri reverted to pentobarbital amid ongoing litigation, rendering propofol's role in U.S. capital punishment prospective rather than realized.[58]Recreational Abuse and Dependence

Propofol, an intravenous anesthetic, is subject to recreational abuse primarily for its rapid induction of euphoria, hallucinations, and dissociative states, effects that users often describe as intensely pleasurable and amnesic.[59] This abuse is facilitated by the drug's short half-life, allowing quick recovery and repeated dosing without prolonged impairment, though it carries severe risks of respiratory depression and cardiovascular instability when self-administered without medical monitoring.[60] The euphoric response arises from propofol's enhancement of GABA_A receptor activity, coupled with activation of the mesocorticolimbic dopaminergic pathway, which reinforces seeking behavior and contributes to psychological dependence.[61] [62] Abuse is disproportionately prevalent among healthcare professionals, particularly anesthesiologists and nurses, due to occupational access and familiarity with administration techniques.[63] Between 1992 and 2009, 89% of reported propofol abuse cases involved healthcare workers, with surveys estimating an incidence of approximately 10 cases per 10,000 U.S. anesthesia providers over a decade.[63] [64] Dependence manifests as cravings, tolerance requiring escalating doses, and relapse vulnerability mediated by dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in brain regions like the basolateral amygdala, prompting compulsive use despite awareness of lethality.[59] Animal and human studies confirm propofol's capacity to trigger addiction-like behaviors, including conditioned place preference and withdrawal symptoms such as anxiety upon cessation.[61] Fatal outcomes are common in recreational use, with mortality rates exceeding 50% among identified abusers in some analyses, largely attributable to apnea and lack of ventilatory support.[59] Of 21 documented fatal propofol abuse cases reviewed, 86% involved healthcare workers, including 67% anesthesiologists or nurse anesthetists; in Korea, 36 propofol-related deaths from 2000 to 2011 included 20 abuse cases, over 70% among medical staff.[65] [66] While overall prevalence remains low—estimated at 1 per 1,000 anesthesiologists per decade—the narrow therapeutic index and absence of antagonists heighten overdose risks, underscoring propofol's profile as a high-potency substance ill-suited for non-medical consumption.[67] Treatment typically involves supervised detoxification, counseling, and monitoring for polysubstance involvement, though success rates are challenged by the drug's rapid reinforcement.[68]Risks and Adverse Effects

Acute Side Effects and Safety Profile

The most frequently reported acute side effect of propofol is transient pain or burning at the injection site, occurring in more than 1% of administrations and often attributable to the emulsion's contact with smaller veins; this can be substantially reduced by pretreating with intravenous lidocaine or using larger veins such as the antecubital fossa.[69][2] Cardiovascular effects include dose-dependent hypotension from vasodilation and mild myocardial depression, with incidence exceeding 1%, particularly pronounced during induction boluses in elderly or hypovolemic patients; bradycardia and arrhythmias are also reported at rates above 1%.[69][2] Respiratory depression manifests as apnea or hypoventilation, common with induction doses (e.g., 2-2.5 mg/kg in adults leading to apnea >60 seconds in 12% of cases), alongside risks of upper airway obstruction, cough, or dyspnea, necessitating immediate airway management capabilities.[69] Neurological acute effects encompass myoclonus and transient excitatory phenomena such as involuntary movements or tremors post-injection, though propofol generally suppresses seizure activity.[2] Rare but serious reactions include anaphylaxis or severe allergic responses (e.g., hives, bronchospasm, swelling), requiring prompt intervention.[70] Propofol maintains a favorable short-term safety profile in controlled clinical settings when administered by trained personnel with continuous monitoring of hemodynamics, ventilation, and oxygenation, as its rapid onset and offset facilitate procedural use; however, its narrow therapeutic window demands avoidance of rapid boluses without supportive measures to mitigate risks of profound cardiorespiratory compromise.[69][2] Contraindications include known hypersensitivity to propofol or its components (e.g., soy or egg-derived lipids), and caution is advised in patients with predisposing factors like hypovolemia or concurrent sedative use that amplify depression of vital functions.[70]Propofol Infusion Syndrome

Propofol infusion syndrome (PRIS) is a rare, potentially fatal complication arising from prolonged high-dose propofol infusions, most commonly observed in critically ill patients receiving sedation in intensive care settings.[71] Defined clinically as acute refractory bradycardia leading to asystole, accompanied by at least one of metabolic acidosis, rhabdomyolysis, hypertriglyceridemia, or renal or hepatic failure, PRIS typically manifests after infusions exceeding 4–5 mg/kg/hour for over 48 hours, though cases have occurred at lower doses or shorter durations.[72][73] Early recognition is critical, as the syndrome involves multi-organ dysfunction driven by propofol's interference with cellular metabolism. The hallmark features include unexplained metabolic acidosis with elevated lactate levels, evidence of muscle breakdown indicated by rising creatine kinase concentrations, and cardiac instability ranging from sinus bradycardia to electromechanical dissociation.[74] Hypertriglyceridemia, often exceeding 1,000 mg/dL, stems from propofol's lipid emulsion vehicle, while renal and hepatic impairments reflect systemic hypoperfusion and direct toxicity.[75] In reported cases, electrocardiographic changes such as progressive PR interval prolongation, bundle branch blocks, or Brugada-like patterns precede hemodynamic collapse.[76] Mortality rates in documented PRIS cases range from 48% in adults to 52% in children, with overall figures around 50%, though early intervention has reduced fatalities in recent series.[77] Pathophysiologically, PRIS likely results from propofol-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, impairing beta-oxidation of fatty acids and leading to energy failure in high-demand tissues like cardiac and skeletal muscle.[76] Propofol's phenolic structure inhibits carnitine palmitoyltransferase, exacerbating accumulation of toxic lipid intermediates, while co-factors such as endogenous catecholamines or exogenous vasopressors may amplify oxidative stress.[78] Experimental models confirm dose-dependent reductions in mitochondrial respiratory chain activity, supporting a causal link beyond mere lipid overload from the emulsion.[76] Risk factors include critical illness with traumatic brain injury, sepsis, or low carbohydrate states, which heighten susceptibility by promoting reliance on fatty acid metabolism.[75] Concomitant use of corticosteroids or catecholamine infusions increases odds, as does pediatric age or young adulthood, with incidence estimates varying from 1% in broad ICU cohorts to 2.9% in high-risk trauma populations.[79][80] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued warnings in 2001 following pediatric fatalities, updating propofol labeling in 2006 to cap sedation doses at 4 mg/kg/hour and contraindicate prolonged use in children under 3 years or those with mitochondrial disorders.[78] Diagnosis relies on clinical suspicion in propofol-exposed patients developing compatible features, as no single biomarker confirms PRIS; elevated serum propofol levels (>7 mcg/mL) or muscle biopsy showing lipid accumulation provide supportive evidence but are rarely feasible acutely.[81] Management demands immediate propofol cessation, hemodynamic support with fluids and vasopressors, and advanced therapies like extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiac arrest.[82] Supportive measures address acidosis with bicarbonate, rhabdomyolysis via hydration and hemodialysis if needed, and alternative sedation with agents like midazolam or dexmedetomidine.[71] Prevention centers on adhering to dose limits (<4 mg/kg/hour for adults, shorter durations in vulnerable groups), routine monitoring of acid-base status, triglycerides, and creatine kinase, and minimizing propofol in high-risk scenarios such as head injury or carbohydrate restriction.[75] Guidelines from bodies like the Society of Critical Care Medicine recommend propofol for short-term sedation only, with daily interruptions to assess need and early signs of toxicity prompting switches to non-lipid-based sedatives.[83] Despite these measures, PRIS underscores propofol's narrow therapeutic window in prolonged use, with ongoing research exploring genetic predispositions like polymorphisms in lipid metabolism genes.[77]Overdose and Fatality Risks

Propofol overdose induces profound respiratory depression, apnea, and hypotension due to its potent GABA_A receptor agonism, which suppresses central respiratory drive and vasomotor centers.[84] These effects occur rapidly, often within seconds of intravenous administration, and can progress to hypoxia, cardiac arrest, and death without immediate airway management and hemodynamic support.[85] Unlike many sedatives, propofol lacks a specific antidote, requiring supportive interventions such as mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, and fluid resuscitation to mitigate fatality risks.[86] Fatal outcomes predominate in non-clinical settings, where lack of monitoring exacerbates the drug's narrow therapeutic index; therapeutic plasma levels range from 1-5 μg/mL for sedation, but concentrations above 5-10 μg/mL are commonly associated with lethal respiratory failure in postmortem analyses.[84] Case reports document self-administration leading to blood propofol levels of 92 μg/mL, resulting in acute intoxication and cardiorespiratory collapse.[87] Co-ingestion with opioids or benzodiazepines synergistically heightens mortality by compounding respiratory suppression, as evidenced in forensic examinations where propofol alone rarely causes direct myocardial toxicity but indirectly precipitates arrest via hypoxia.[84] Notable fatalities include the 2009 death of Michael Jackson, where autopsy confirmed acute propofol intoxication (blood level approximately 3.2 μg/mL) combined with lorazepam as the primary cause of cardiac arrest, ruled a homicide due to improper administration without monitoring equipment.[88] Similar patterns appear in healthcare professional suicides and accidental overdoses, such as a 29-year-old radiographer's self-injection fatality and an anesthetic nurse's misuse yielding toxic levels, underscoring the drug's abuse potential and near-certain lethality absent professional oversight.[89][87] In clinical trials and reports, supervised overdose incidents yield survival rates approaching 100% with prompt intervention, contrasting sharply with recreational or diversionary use where mortality exceeds 50% due to delayed recognition.[84]Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Propofol exerts its pharmacological effects primarily as a positive allosteric modulator of the γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA_A) receptor, enhancing the inhibitory neurotransmission mediated by GABA, the principal inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS).[10][4] This modulation increases the frequency of chloride channel opening without altering channel conductance duration, resulting in chloride influx, neuronal membrane hyperpolarization, and reduced neuronal excitability.[2][90] Binding occurs at a distinct site on the β-subunit of the GABA_A receptor, distinct from the GABA-binding site, with propofol demonstrating higher affinity for receptors containing β3 subunits.[90][91] At clinically relevant concentrations (approximately 1-10 μM), propofol potentiates GABA-evoked currents by 100-300%, contributing to rapid-onset sedation, hypnosis, anterograde amnesia, and suppression of epileptiform activity.[10][2] Higher concentrations (above 20 μM) enable direct receptor activation independent of GABA, prolonging channel open times and amplifying CNS depression.[9] These actions lead to dose-dependent reductions in cerebral blood flow, cerebral metabolic oxygen consumption (by up to 40-50%), and intracranial pressure, beneficial in neuroanesthesia.[4] Antiemetic effects arise from suppression of the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the area postrema, though the precise mechanism remains incompletely elucidated beyond GABAergic potentiation.[2] Beyond the CNS, propofol induces peripheral vasodilation and myocardial depression via diminished sympathetic outflow and direct effects on vascular smooth muscle calcium flux, reducing systemic vascular resistance and mean arterial pressure by 20-30% at induction doses.[90][19] It also inhibits excitatory neurotransmission at glutamatergic NMDA receptors and modulates two-pore domain potassium channels, contributing to overall hypnotic efficacy, though these are secondary to GABA_A interactions.[10] The drug's pharmacodynamic profile supports brief procedures due to its steep dose-response curve and minimal accumulation with short infusions.[4]Pharmacokinetics

Propofol is administered exclusively via intravenous injection or infusion, achieving 100% bioavailability and rapid onset of action within 30-60 seconds due to its high lipid solubility and quick equilibration across the blood-brain barrier.[10] [8] Distribution occurs in three phases: an initial rapid phase (half-life of 1.8-9.5 minutes) reflecting uptake into highly perfused tissues like the brain, followed by redistribution to muscle and fat (half-life 21-70 minutes), and a slower terminal phase.[10] The volume of distribution at steady state ranges from 159-771 L (approximately 2-10 L/kg in adults), influenced by factors such as age and obesity, with higher values in children and lower in the elderly.[4] Propofol is highly protein-bound (95-99%), primarily to albumin and alpha-1-acid glycoprotein, with a free fraction of 1.2-1.7%; it also binds to erythrocytes (up to 50%).[10] [4] Metabolism is primarily hepatic, involving glucuronidation (70% to propofol glucuronide) and CYP2B6/CYP2C9-mediated hydroxylation to 4-hydroxypropofol (29%), yielding water-soluble inactive metabolites; extrahepatic metabolism accounts for about 40% of clearance, occurring in kidneys (60-70% extraction) and small intestine (24%).[4] [10] Elimination occurs mainly via renal excretion of metabolites, with 88% recovered in urine within 5 days and less than 0.3% as unchanged drug; minor exhalation of metabolites occurs at parts-per-billion levels.[4] Total clearance is high at 1.78-2.28 L/min (or 23-50 mL/kg/min), reflecting hepatic blood flow dependency.[4] [10] The terminal elimination half-life varies widely (1.5-31 hours or 116-834 minutes), but clinical recovery is primarily driven by redistribution rather than elimination, with context-sensitive half-times under 40 minutes for infusions up to 8 hours.[10] [8]Chemistry, Formulation, and Manufacturing

Chemical Structure and Properties

Propofol is systematically named 2,6-di(propan-2-yl)phenol, also known as 2,6-diisopropylphenol, consisting of a phenol ring substituted with two isopropyl groups at the 2- and 6-positions.[1] Its molecular formula is C₁₂H₁₈O, with a molecular weight of 178.27 g/mol.[1] The compound exists as a viscous, colorless to pale-yellow liquid at room temperature, possessing a faint phenolic odor.[92] It has a melting point of 18 °C and a boiling point of 256 °C at 760 mmHg.[1] [92]| Property | Value | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Density | 0.955–0.962 g/mL | 20–25 °C |

| Water solubility | 124 mg/L | 25 °C |

| Solubility in organics | Soluble | Ethanol, toluene |

| LogP (octanol-water) | 3.79 | - |

| Vapor pressure | 3.1 × 10⁻³ mm Hg | 25 °C (estimated) |

Formulations and Administration

Propofol is formulated as a sterile, nonpyrogenic oil-in-water emulsion for intravenous administration, typically containing 10 mg/mL of propofol dissolved in soybean oil (100 mg/mL), with egg lecithin (12 mg/mL) as the emulsifier, glycerol (22.5 mg/mL) for isotonicity, and disodium edetate (0.005%) in some versions to inhibit microbial growth.[93] The emulsion's characteristic milky white appearance results from its lipid composition, which supports rapid onset but requires strict aseptic handling to prevent bacterial contamination, as the medium can promote growth of pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus.[2] A higher concentration formulation (20 mg/mL) exists for scenarios requiring smaller volumes, maintaining similar excipient ratios.[94] Administration is exclusively intravenous, with propofol delivered via bolus injection for induction of anesthesia or continuous infusion for maintenance and sedation, titrated to clinical effect under continuous monitoring of vital signs, oxygenation, and ventilation.[2] For induction of general anesthesia in unpremedicated adults aged 18-65, an initial dose of 2-2.5 mg/kg is administered intravenously over 20-40 seconds, with supplemental boluses of 25-50 mg as needed until onset.[20] Maintenance typically involves infusion rates of 100-200 mcg/kg/min, adjustable based on response, while procedural sedation starts at 0.5-1 mg/kg bolus followed by 25-75 mcg/kg/min infusion.[19] In elderly or debilitated patients, doses are reduced by 20-25% (e.g., 1-1.5 mg/kg induction), and for children over 3 years, higher induction doses of 2.5-3.5 mg/kg may be required.[20] Propofol must be administered only by qualified anesthesia personnel, with readiness for airway management due to risks of respiratory depression.[15]| Patient Group | Induction Dose (mg/kg IV) | Maintenance Infusion (mcg/kg/min) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults (18-65, healthy) | 2-2.5 | 100-200 | Titrate to effect; unpremedicated.[20] |

| Elderly/Debilitated | 1-1.5 | 50-100 | Reduce by 20-25%; monitor closely.[20] |

| Children (>3 years) | 2.5-3.5 | 125-300 | Higher rates due to faster clearance.[20] |

| ICU Sedation | N/A | 5-50 (start low) | Avoid >4 mg/kg/hr to prevent infusion syndrome.[19] |

Production Challenges and Supply Shortages