Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Protected mode

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2025) |

| Part of a series on |

| Microprocessor modes for the x86 architecture |

|---|

|

| First supported platform shown in parentheses |

In computing, protected mode, also called protected virtual address mode,[1] is an operational mode of x86-compatible central processing units (CPUs). It allows system software to use features such as segmentation, virtual memory, paging and safe multi-tasking designed to increase an operating system's control over application software.[2][3]

When a processor that supports x86 protected mode is powered on, it begins executing instructions in real mode, in order to maintain backward compatibility with earlier x86 processors.[4] Protected mode may only be entered after the system software sets up one descriptor table and enables the Protection Enable (PE) bit in the control register 0 (CR0).[5]

Protected mode was first added to the x86 architecture in 1982,[6] with the release of Intel's 80286 (286) processor, and later extended with the release of the 80386 (386) in 1985.[7] Due to the enhancements added by protected mode, it has become widely adopted and has become the foundation for all subsequent enhancements to the x86 (IA-32) architecture,[8] although many of those enhancements, such as added instructions and new registers, also brought benefits to the real mode.

History

[edit]The first x86 processor, the Intel 8086, had a 20-bit address bus for its memory, as did its Intel 8088 variant.[9] This allowed them to access 220 bytes of memory, equivalent to 1 megabyte.[9] At the time, 1 megabyte was considered a relatively large amount of memory,[10] so the designers of the IBM Personal Computer reserved the first 640 kilobytes for use by applications and the operating system and the remaining 384 kilobytes for the BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) and memory for add-on devices.[11]

As the cost of memory decreased and memory use increased, the 1 MB limitation became a significant problem. Intel intended to solve this limitation along with others with the release of the 286.[11]

The 286

[edit]The initial protected mode, released with the 286, was not widely used;[11] for example, it was used by Coherent (from 1982),[12] Microsoft Xenix (around 1984)[13] and Minix.[14] Several shortcomings such as the inability to make BIOS and DOS calls due to inability to switch back to real mode without resetting the processor prevented widespread usage.[15] Acceptance was additionally hampered by the fact that the 286 allowed memory access in 64 kilobyte segments, addressed by its four segment registers, meaning that only 4 × 64 KB, equivalent to 256 KB, could be accessed at a time.[11] Because changing a segment register in protected mode caused a 6-byte segment descriptor to be loaded into the CPU from memory, the segment register load instruction took many tens of processor cycles, making it much slower than on the 8086 and 8088; therefore, the strategy of computing segment addresses on-the-fly in order to access data structures larger than 128 kilobytes (the combined size of the two data segments) became impractical, even for those few programmers who had mastered it on the 8086 and 8088.

The 286 maintained backward compatibility with the 8086 and 8088 by initially entering real mode on power up.[4] Real mode functioned virtually identically to the 8086 and 8088, allowing the vast majority of existing software for those processors to run unmodified on the newer 286. Real mode also served as a more basic mode to set up and bootstrap into protected mode. To access the extended functionality of the 286, the operating system would set up some tables in memory that controlled memory access in protected mode, set the addresses of those tables into some special registers of the processor, and then set the processor into protected mode. This enabled 24-bit addressing, which allowed the processor to access 224 bytes of memory, equivalent to 16 megabytes.[9]

The 386

[edit]

With the release of the 386 in 1985,[7] many of the issues preventing widespread adoption of the previous protected mode were addressed.[11] The 386 was released with an address bus size of 32 bits, which allows for 232 bytes of memory accessing, equivalent to 4 gigabytes.[16] The segment sizes were also increased to 32 bits, meaning that the full address space of 4 gigabytes could be accessed without the need to switch between multiple segments.[16] In addition to the increased size of the address bus and segment registers, many other new features were added with the intention of increasing operational security and stability.[17] Protected mode is now used in virtually all modern operating systems which run on the x86 architecture, such as Microsoft Windows, Linux, and many others.[18]

Furthermore, learning from the failures of the 286 protected mode to satisfy the needs for multiuser DOS, Intel added a separate virtual 8086 mode,[19] which allowed multiple virtualized 8086 processors to be emulated on the 386. Hardware x86 virtualization required for virtualizing the protected mode itself, however, had to wait for another 20 years.[20]

386 additions to protected mode

[edit]With the release of the 386, the following additional features were added to protected mode:[2]

- Paging

- 32-bit physical and virtual address space (The 32-bit physical address space is not present on the 80386SX, and other 386 processor variants which use the older 286 bus.[21])

- 32-bit segment offsets

- Ability to switch back to real mode without resetting

- Virtual 8086 mode

Entering and exiting protected mode

[edit]Until the release of the 386, protected mode did not offer a direct method to switch back into real mode once protected mode was entered. IBM devised a workaround (implemented in the IBM AT) which involved resetting the CPU via the keyboard controller and saving the system registers, stack pointer and often the interrupt mask in the real-time clock chip's RAM. This allowed the BIOS to restore the CPU to a similar state and begin executing code before the reset.[clarification needed] Later, a triple fault was used to reset the 286 CPU, which was a lot faster and cleaner than the keyboard controller method.

To enter protected mode, the Global Descriptor Table (GDT) must first be created with a minimum of three entries: a null descriptor, a code segment descriptor and data segment descriptor. Then, the PE bit must be set in the CR0 register and a far jump must be made to clear the prefetch input queue.[22][23] Also, on an IBM-compatible machine, in order to enable the CPU to access all 16 MB of the address space (instead of only the 8 even megabytes), the A20 line (21st address line) must be enabled. (A20 is disabled at power-up, causing each odd megabyte of the address space to be aliased to the previous even megabyte, in order to guarantee compatibility with older software written for the Intel 8088-based IBM PC and PC/XT models).[24] Enabling A20 is not strictly required to run in protected mode; the CPU will operate normally in protected mode with A20 disabled, only without the ability to access half of the memory addresses.

; MASM program

; enter protected mode (set PE bit)

mov EBX, CR0 ; save control register 0 (CR0) to EBX

or EBX, PE_BIT ; set PE bit by ORing, save to EBX

mov CR0, EBX ; save EBX back to CR0

; clear prefetch queue; (using far jump instruction jmp)

jmp CLEAR_LABEL

CLEAR_LABEL:

With the release of the 386, protected mode could be exited by loading the segment registers with real mode values, disabling the A20 line and clearing the PE bit in the CR0 register, without the need to perform the initial setup steps required with the 286. [25]

Features

[edit]Protected mode has a number of features designed to enhance an operating system's control over application software, in order to increase security and system stability.[3] These additions allow the operating system to function in a way that would be significantly more difficult or even impossible without proper hardware support.[26]

Privilege levels

[edit]

In protected mode, there are four privilege levels or rings, numbered from 0 to 3, with ring 0 being the most privileged and 3 being the least. The use of rings allows for system software to restrict tasks from accessing data, call gates or executing privileged instructions.[27] In most environments, the operating system and some device drivers run in ring 0 and applications run in ring 3.[27]

Real mode application compatibility

[edit]According to the Intel 80286 Programmer's Reference Manual,[28]

the 80286 remains upwardly compatible with most 8086 and 80186 application programs. Most 8086 application programs can be re-compiled or re-assembled and executed on the 80286 in Protected Mode.

For the most part, the binary compatibility with real-mode code, the ability to access up to 16 MB of physical memory, and 1 GB of virtual memory, were the most apparent changes to application programmers.[29] This was not without its limitations. If an application utilized or relied on any of the techniques below, it would not run:[30]

- Segment arithmetic

- Privileged instructions

- Direct hardware access

- Writing to a code segment

- Executing data

- Overlapping segments

- Use of BIOS functions, due to the BIOS interrupts being reserved by Intel[31]

In reality, almost all DOS application programs violated these rules.[32] Due to these limitations, virtual 8086 mode was introduced with the 386. Despite such potential setbacks, Windows 3.0 and its successors can take advantage of the binary compatibility with real mode to run many Windows 2.x (Windows 2.0 and Windows 2.1x) applications in protected mode, which ran in real mode in Windows 2.x.[33]

Virtual 8086 mode

[edit]With the release of the 386, protected mode offers what the Intel manuals call virtual 8086 mode. Virtual 8086 mode is designed to allow code previously written for the 8086 to run unmodified and concurrently with other tasks, without compromising security or system stability.[34]

Virtual 8086 mode, however, is not completely backward compatible with all programs. Programs that require segment manipulation, privileged instructions, direct hardware access, or use self-modifying code will generate an exception that must be served by the operating system.[35] In addition, applications running in virtual 8086 mode generate a trap with the use of instructions that involve input/output (I/O), which can negatively impact performance.[36]

Due to these limitations, some programs originally designed to run on the 8086 cannot be run in virtual 8086 mode. As a result, system software is forced to either compromise system security or backward compatibility when dealing with legacy software. An example of such a compromise can be seen with the release of Windows NT, which dropped backward compatibility for "ill-behaved" DOS applications.[37]

Segment addressing

[edit]

Real mode

[edit]In real mode each logical address points directly into a physical memory location, every logical address consists of two 16-bit parts: The segment part of the logical address contains the base address of a segment with a granularity of 16 bytes, i.e. a segment may start at physical address 0, 16, 32, ..., 220 − 16. The offset part of the logical address contains an offset inside the segment, i.e. the physical address can be calculated as physical_address = segment_part × 16 + offset, if the address line A20 is enabled, or (segment_part × 16 + offset) mod 220, if A20 is off.[clarification needed] Every segment has a size of 216 bytes.

Protected mode

[edit]In protected mode, the segment_part is replaced by a 16-bit selector, in which the 13 upper bits (bit 3 to bit 15) contain the index of an entry inside a descriptor table. The next bit (bit 2) specifies whether the operation is used with the GDT or the LDT. The lowest two bits (bit 1 and bit 0) of the selector are combined to define the privilege of the request, where the values of 0 and 3 represent the highest and the lowest privilege, respectively. This means that the byte offset of descriptors in the descriptor table is the same as the 16-bit selector, provided the lower three bits are zeroed.

The descriptor table entry defines the real linear address of the segment, a limit value for the segment size, and some attribute bits (flags).

286

[edit]The segment address inside the descriptor table entry has a length of 24 bits so every byte of the physical memory can be defined as bound of the segment. The limit value inside the descriptor table entry has a length of 16 bits so segment length can be between 1 byte and 216 byte. The calculated linear address equals the physical memory address.

386

[edit]The segment address inside the descriptor table entry is expanded to 32 bits so every byte of the physical memory can be defined as bound of the segment. The limit value inside the descriptor table entry is expanded to 20 bits and completed with a granularity flag (G-bit, for short):

- If G-bit is zero limit has a granularity of 1 byte, i.e. segment size may be 1, 2, ..., 220 bytes.

- If G-bit is one limit has a granularity of 212 bytes, i.e. segment size may be 1 × 212, 2 × 212, ..., 220 × 212 bytes. If paging is off, the calculated linear address equals the physical memory address. If paging is on, the calculated linear address is used as input of paging.

The 386 processor also uses 32 bit values for the address offset.

For maintaining compatibility with 286 protected mode a new default flag (D-bit, for short) was added. If the D-bit of a code segment is off (0) all commands inside this segment will be interpreted as 16-bit commands by default; if it is on (1), they will be interpreted as 32-bit commands.

Structure of segment descriptor entry

[edit]| 80286 Segment descriptor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 80386 Segment descriptor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Where:

- A is the Accessed bit;

- R is the Readable bit;

- C (Bit 42) depends on X:[38]

- if X = 1 then C is the Conforming bit, and determines which privilege levels can far-jump to this segment (without changing privilege level):

- if C = 0 then only code with the same privilege level as DPL may jump here;

- if C = 1 then code with the same or a lower privilege level relative to DPL may jump here.

- if X = 0 then C is the direction bit:

- if C = 0 then the segment grows up;

- if C = 1 then the segment grows down.

- if X = 1 then C is the Conforming bit, and determines which privilege levels can far-jump to this segment (without changing privilege level):

- X is the Executable bit:[38]

- if X = 1 then the segment is a code segment;

- if X = 0 then the segment is a data segment.

- S is the Segment type bit, which should generally be cleared for system segments;[38]

- DPL is the Descriptor Privilege Level;

- P is the Present bit;

- D is the Default operand size;

- G is the Granularity bit;

- Bit 52 of the 80386 descriptor is not used by the hardware.

Paging

[edit]

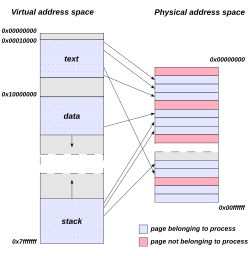

In addition to adding virtual 8086 mode, the 386 also added paging to protected mode.[39] Through paging, system software can restrict and control a task's access to pages, which are sections of memory. In many operating systems, paging is used to create an independent virtual address space for each task, preventing one task from manipulating the memory of another. Paging also allows for pages to be moved out of primary storage and onto a slower and larger secondary storage, such as a hard disk drive.[40] This allows for more memory to be used than physically available in primary storage.[40]

The x86 architecture allows control of pages through two arrays: page directories and page tables. Originally, a page directory was the size of one page, four kilobytes, and contained 1,024 page directory entries (PDE), although subsequent enhancements to the x86 architecture have added the ability to use larger page sizes. Each PDE contained a pointer to a page table. A page table was also originally four kilobytes in size and contained 1,024 page table entries (PTE). Each PTE contained a pointer to the actual page's physical address and are only used when the four-kilobyte pages are used. At any given time, only one page directory may be in active use.[41]

Multitasking

[edit]Through the use of the rings, privileged call gates, and the Task State Segment (TSS), introduced with the 286, preemptive multitasking was made possible on the x86 architecture. The TSS allows general-purpose registers, segment selector fields, and stacks to all be modified without affecting those of another task. The TSS also allows a task's privilege level, and I/O port permissions to be independent of another task's.

In many operating systems, the full features of the TSS are not used.[42] This is commonly due to portability concerns or due to the performance issues created with hardware task switches.[42] As a result, many operating systems use both hardware and software to create a multitasking system.[43]

Operating systems

[edit]Operating systems like OS/2 1.x try to switch the processor between protected and real modes. This is both slow and unsafe, because a real mode program can easily crash a computer. OS/2 1.x defines restrictive programming rules allowing a Family API or bound program to run in either real or protected mode. Some early Unix operating systems, OS/2 1.x, and Windows used this mode.

Windows 3.0 was able to run real mode programs in 16-bit protected mode; when switching to protected mode, it decided to preserve the single privilege level model that was used in real mode, which is why Windows applications and DLLs can hook interrupts and do direct hardware access. That lasted through the Windows 9x series. If a Windows 1.x or 2.x program is written properly and avoids segment arithmetic, it will run the same way in both real and protected modes. Windows programs generally avoid segment arithmetic because Windows implements a software virtual memory scheme, moving program code and data in memory when programs are not running, so manipulating absolute addresses is dangerous; programs should only keep handles to memory blocks when not running. Starting an old program while Windows 3.0 is running in protected mode triggers a warning dialog, suggesting to either run Windows in real mode or to obtain an updated version of the application. Updating well-behaved programs using the MARK utility with the MEMORY parameter avoids this dialog. It is not possible to have some GUI programs running in 16-bit protected mode and other GUI programs running in real mode. In Windows 3.1, real mode was no longer supported and could not be accessed.

In modern 32-bit operating systems, virtual 8086 mode is still used for running applications, e.g. DPMI compatible DOS extender programs (through virtual DOS machines) or Windows 3.x applications (through the Windows on Windows subsystem) and certain classes of device drivers (e.g. for changing the screen-resolution using BIOS functionality) in OS/2 2.0 (and later OS/2) and 32-bit Windows NT, all under control of a 32-bit kernel. However, 64-bit operating systems (which run in long mode) no longer use this, since virtual 8086 mode has been removed from long mode.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Memory access control method and system for realizing the same". US Patent 5483646. May 23, 1995. Archived from the original (Patent) on September 26, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

The memory access control system according to claim 4, wherein said first address mode is a real address mode, and said second address mode is a protected virtual address mode.

- ^ a b Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Volume 1: Basic Architecture. Intel. May 2019. Section 2.1.3 The Intel 386 Processor (1985).

- ^ a b root (July 14, 2007). "Guide: What does protected mode mean?" (Guide). Delorie Software. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

The purpose of protected mode is not to protect your program. The purpose is to protect everyone else (including the operating system) from your program.

- ^ a b Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Volume 1: Basic Architecture. Intel. May 2019. Section 3.1 Modes of Operation.

- ^ Collins, Robert (2007). "Protected Mode Basics". Retrieved 2025-07-21.

- ^ Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Volume 1: Basic Architecture. Intel. May 2019. Section 2.1.2 The Intel 286 Processor (1982).

- ^ a b "Intel Global Citizenship Report 2003". Archived from the original (Timeline) on 2008-03-22. Retrieved 2007-07-14.

1985 Intel launches Intel386 processor

- ^ Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Volume 1: Basic Architecture. Intel. May 2019. Section 2.1 Brief History of Intel 64 and IA-32 Architecture.

- ^ a b c "A+ - Hardware" (Tutorial/Guide). PC Microprocessor Developments and Features Tutorials. BrainBell.com. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ Risley, David (March 23, 2001). "A CPU History". PCMechanic. Archived from the original (Article) on August 29, 2008. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

What is interesting is that the designers of the time never suspected anyone would ever need more than 1 MB of RAM.

- ^ a b c d e Kaplan, Yariv (1997). "Introduction to Protected-Mode". Internals.com. Archived from the original (Article) on 2007-06-22. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ^ "General Information FAQ for the Coherent Operating System". January 23, 1993.

- ^ "Microsoft XENIX 286 Press Release" (PDF) (Press release). Microsoft. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-21. Retrieved 2015-08-17.

- ^ "MINIX Information Sheet". Archived from the original on January 7, 2014.

- ^ Mueller, Scott (March 24, 2006). "P2 (286) Second-Generation Processors". Upgrading and Repairing PCs, 17th Edition (Book) (17 ed.). Que. ISBN 0-7897-3404-4. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

- ^ a b 80386 Programmer's Reference Manual (PDF). Santa Clara, CA: Intel. 1986. Section 2.1 Memory Organization and Segmentation.

- ^ Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Volume 1: Basic Architecture. Intel. May 2019. Section 3.1 Modes of Operation.

- ^ Hyde, Randall (November 2004). "12.10. Protected Mode Operation and Device Drivers". Write Great Code. O'Reilly. ISBN 1-59327-003-8.

- ^ Charles Petzold, Intel's 32-bit Wonder: The 80386 Microprocessor, PC Magazine, November 25, 1986, pp. 150-152

- ^ Tom Yager (6 November 2004). "Sending software to do hardware's job". InfoWorld. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ Shvets, Gennadiy (June 3, 2007). "Intel 80386 processor family" (Article). Retrieved 2007-07-24.

80386SX — low cost version of the 80386. This processor had 16 bit external data bus and 24-bit external address bus.

- ^ "Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Combined Volumes 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D: System Programming Guide". Intel. 9.9.1 Switching to Protected Mode, page 9-13.

- ^ "Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Combined Volumes 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D: System Programming Guide". Intel. Section 9.10.2 STARTUP.ASM Listing, page 9-19.

- ^ "Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Combined Volumes 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D: System Programming Guide". Intel. Section 21.33.1 Segment Wraparound, page 21-34.

- ^ "Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Combined Volumes 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D: System Programming Guide". Intel. Section 9.9.2 Switching Back to Real-Address Mode, page 9-14.

- ^ Intel 80386 Programmer's Reference Manual 1986 (PDF). Santa Clara, CA: Intel. 1986. Chapter 7, Multitasking.

- ^ a b Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Volume 1: Basic Architecture. Intel. May 2019. Section 6.3.5 Calls to Other Privilege Levels.

- ^ 80286 and 80287 Programmer's Reference Manual (PDF). Santa Clara, CA: Intel. 1987. Section 1.2 Modes of Operation.

- ^ 80286 and 80287 Programmer's Reference Manual (PDF). Santa Clara, California: Intel. 1987. Section 1.3.1 Memory Management.

- ^ 80286 and 80287 Programmer's Reference Manual (PDF). Santa Clara, California: Intel. 1987. Appendix C 8086/8088 Compatibility Considerations.

- ^ "Memory access control method and system for realizing the same" (Patent). US Patent 5483646. May 6, 1998. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

This has been impossible to-date and has forced BIOS development teams to add support into the BIOS for 32 bit function calls from 32 bit applications.

- ^ Robinson, Tim (August 26, 2002). "Virtual 8086 Mode". berliOS. Archived from the original (Guide) on October 3, 2002. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

... secondly, protected mode was also incompatible with the vast amount of real-mode code around at the time.

- ^ Robinson, Tim (August 26, 2002). "Virtual 8086 Mode". berliOS. Archived from the original (Guide) on October 3, 2002. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- ^ Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Combined Volumes 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D: System Programming Guide. Intel. May 2019. Section 20.2 Virtual 8086 Mode.

- ^ Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Combined Volumes 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D: System Programming Guide. Intel. May 2019. Section 20.2.7 Sensitive Instructions.

- ^ Robinson, Tim (August 26, 2002). "Virtual 8086 Mode". berliOS. Archived from the original (Guide) on October 3, 2002. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

A downside to using V86 mode is speed: every IOPL-sensitive instruction will cause the CPU to trap to kernel mode, as will I/O to ports which are masked out in the TSS.

- ^ Dabak, Prasad; Millind Borate (October 1999). Undocumented Windows NT (Book). Hungry Minds. ISBN 0-7645-4569-8.

- ^ a b c "Global Descriptor table - OSDev Wiki".

- ^ "ProtectedMode overview [deinmeister.de]" (Website). Retrieved 2007-07-29.

- ^ a b "What Is PAE X86?". Microsoft TechNet. May 28, 2003. Archived from the original (Article) on 2008-04-22. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

The paging process allows the operating system to overcome the real physical memory limits. However, it also has a direct impact on performance because of the time necessary to write or retrieve data from disk.

- ^ Gareau, Jean. "Advanced Embedded x86 Programming: Paging". Embedded.com. Archived from the original (Guide) on 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

Only one page directory may be active at a time, indicated by the CR3 register.

- ^ a b zwanderer (May 2, 2004). "news: Multitasking for x86 explained #1". NewOrer. NewOrder. Archived from the original (Article) on 2007-02-12. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

The reason why software task switching is so popular is that it can be faster than hardware task switching. Intel never actually developed the hardware task switching, they implemented it, saw that it worked, and just left it there. Advances in multitasking using software have made this form of task switching faster (some say up to 3 times faster) than the hardware method. Another reason is that the Intel way of switching tasks isn't portable at all

- ^ zwanderer (May 2, 2004). "news: Multitasking for x86 explained #1". NewOrer. NewOrder. Archived from the original (Article) on 2007-02-12. Retrieved 2007-07-29.

... both rely on the Intel processors ability to switch tasks, they rely on it in different ways.

External links

[edit]Protected mode

View on GrokipediaBackground

Real Mode Basics

Real mode, also known as real-address mode, is the default operational state of x86 processors upon power-up or reset, providing backward compatibility with the original Intel 8086 and 8088 architectures.[2] In this mode, the processor employs a 20-bit physical address space, restricting accessible memory to a maximum of 1 MB (2^20 bytes).[2] Addressing operates through a segment:offset scheme, where memory locations are specified by combining a 16-bit segment value from a segment register with a 16-bit offset.[2] The x86 architecture includes four primary 16-bit segment registers in real mode: CS (code segment), which points to the current code segment; DS (data segment), used for data access; SS (stack segment), for stack operations; and ES (extra segment), for additional data.[2] To form a physical address, the segment value is shifted left by 4 bits (effectively multiplied by 16) to establish the segment base, and the offset is then added to this base.[2] For example, the physical address is calculated as .[2] This segmented approach limits each individual segment to a maximum size of 64 KB (2^16 bytes), as the offset is only 16 bits wide.[2] Furthermore, real mode provides no hardware-enforced memory protection, allowing programs unrestricted access to the entire addressable memory space without checks for bounds or privileges.[2] These characteristics establish the foundational model from which protected mode evolved to address growing demands for larger memory and security.[2]Limitations and Motivations

Real mode, the default operating mode of early x86 processors like the Intel 8086, imposed significant constraints that hindered the evolution of personal computing systems. Primarily, it provided no inherent memory protection mechanisms, allowing errant or malicious code to access and corrupt any part of the system's 1 MB address space, which frequently led to crashes or security vulnerabilities in multi-program environments. This 1 MB ceiling stemmed from the 20-bit physical addressing scheme, where segmented addressing—combining a 16-bit segment register shifted left by 4 bits with a 16-bit offset—effectively capped usable memory at 2^20 bytes, restricting scalability as RAM capacities grew beyond this limit in the early 1980s. Furthermore, real mode lacked support for native multitasking, forcing operating systems to rely on cumbersome software techniques like time-slicing or bank switching to simulate concurrent program execution, which were inefficient and prone to errors.[3] These limitations motivated the development of protected mode as a foundational shift toward more robust, secure, and scalable computing architectures. The primary drivers included the need to support multitasking operating systems such as Unix variants, which required process isolation to prevent one application from interfering with others, thereby enabling safer multiuser environments on emerging PCs. Protection against malicious software was another key impetus, as growing software complexity in the 1980s amplified risks from faulty or intentionally harmful code, necessitating hardware-enforced boundaries to enhance system reliability. Additionally, the demand for larger memory addressing arose from hardware advancements allowing RAM beyond 1 MB, compelling designs that could leverage up to 16 MB of physical memory while maintaining compatibility with existing 8086 software.[3][4] Historically, protected mode drew inspiration from minicomputer operating systems that emphasized isolation and resource sharing, influencing Intel's response to pressures from developers seeking to port advanced OSes to x86 platforms. Intel's development of the 80286 was informed by six months of field research into customer requirements for enhanced memory addressing and protection mechanisms.[4] Developers, including those at Microsoft who ported XENIX (a Unix derivative) to the 80286, sought features for advanced OS implementations, as real mode's constraints made reliable Unix-like systems impractical on PCs. The 80286, designed starting in 1978 and released in 1982, specifically aimed to bridge 16-bit real-mode compatibility with advanced computing paradigms, incorporating protected mode to address these demands while supporting high-level languages and modular programming for scientific, engineering, and business applications.[4][5][3]Historical Development

Intel 80286 Implementation

The Intel 80286, released in 1982, introduced protected mode as the first implementation of this feature in the x86 architecture, extending the 16-bit iAPX 86/88 family with advanced memory management capabilities.[6] This processor supported 24-bit physical addressing, enabling access to up to 16 MB of physical memory, a significant expansion from the 1 MB limit of prior real-mode systems that relied on 20-bit addressing.[6] In protected mode, the 80286 provided a virtual address space of up to 1 GB per task through segmentation, allowing for more efficient multitasking and isolation without hardware paging support.[6] This mode built on real mode's segment:offset addressing model for compatibility but enforced stricter boundaries to prevent unauthorized access.[6] Key innovations in the 80286's protected mode included the Global Descriptor Table (GDT) and Local Descriptor Table (LDT), which defined segment boundaries and attributes for all processes.[6] The GDT, a system-wide table accessed via the GDTR register, held shared segment descriptors, while the LDT, loaded via the LDTR register, provided task-specific segments for private address spaces.[6] Protection was further enhanced by a four-level privilege hierarchy, known as rings 0 through 3, where ring 0 represented the highest privilege for kernel operations and ring 3 the lowest for user applications.[6] These levels were enforced through the Descriptor Privilege Level (DPL) in segment descriptors and the Current Privilege Level (CPL) in the code segment register, preventing lower-privilege code from accessing sensitive resources.[6] Segment descriptors in the GDT and LDT followed an 8-byte format, specifying the base address (starting location of the segment), limit (up to 64 KB in size), and access rights.[6] Access rights included the present bit (P) to indicate segment validity, type fields for code, data, or system segments, and the DPL for privilege checking.[6] This structure allowed the processor to validate memory references dynamically, generating exceptions for violations such as invalid descriptors or privilege breaches.[6] Despite these advances, the 80286's protected mode had notable limitations, including restriction to 16-bit operations without support for 32-bit extensions, absence of virtual 8086 mode for running real-mode applications natively, and no built-in paging hardware for demand-paged virtual memory.[6] Despite these innovations, the 80286's protected mode saw limited adoption in practice, as it lacked support for running real-mode applications without rebooting and was incompatible with the dominant MS-DOS environment, leading most software to run in real mode.[7] Transitioning to protected mode required software initialization: loading the GDT into the GDTR register using the LGDT instruction, followed by setting the Protection Enable (PE) bit in the Machine Status Word (MSW) via the LMSW instruction at privilege level 0, and finally executing an intra-segment jump to flush the prefetch queue.[6] This process ensured a clean switch but demanded careful setup to avoid faults during the mode change.[6]Intel 80386 Enhancements

The Intel 80386 microprocessor, released in October 1985, introduced 32-bit protected mode, featuring 32-bit general-purpose registers such as EAX, EBX, ECX, and EDX, along with a 32-bit address bus that supported a 4 GB physical address space.[8][9] This marked a significant evolution from the 16-bit protected mode of the Intel 80286, extending the latter's four privilege levels while enabling full 32-bit operations for enhanced performance and scalability in multitasking environments.[9] Key additions included Virtual 8086 (V86) mode, which allowed real-mode 8086 applications to execute within protected mode under multitasking supervision, and a built-in paging unit for virtual memory management.[9] The segment descriptor format was enhanced to support 32-bit addressing, incorporating a granularity bit that permitted segment limits up to 4 GB when set.[9] For compatibility, the 80386 provided Big Real Mode, an unprotected extension enabling 32-bit addressing in real mode to access the full 4 GB space, and enhanced task state segments (TSS) that facilitated efficient context switching for multitasking by storing complete 32-bit processor states.[9] Exclusive to the 80386 were structures like the Page Directory and Page Tables, which formed the basis for demand-paged virtual memory by mapping 4 KB pages in a hierarchical manner.[9] Additionally, the I/O Privilege Level (IOPL) bits in the EFLAGS register (bits 12 and 13) introduced granular control over I/O instructions, restricting sensitive operations to higher privilege levels and enhancing security in protected environments.[9] These features collectively enabled the development of full 32-bit operating systems, such as Microsoft's Windows NT and OS/2 2.0, which leveraged the 80386's capabilities for robust, protected multitasking on personal computers.[10][11]Mode Switching

Entering Protected Mode

To enter protected mode on an x86 processor, specific prerequisites must be met to ensure a stable transition from real mode. The global descriptor table (GDT) must be loaded into memory with at least a null descriptor, a code segment descriptor, and a data segment descriptor; these descriptors define the initial memory segments for code execution and data access in protected mode. A stack must also be established within a data segment to handle any immediate subroutine calls or interrupts post-switch. Interrupts, including non-maskable interrupts (NMIs), should be disabled prior to the switch to prevent interference during the transition.[12] The step-by-step procedure to switch to protected mode involves initializing segment registers to a flat memory model, loading the GDT, enabling the protection enable (PE) bit, and reloading the code segment register (CS). First, initialize the segment registers (DS, ES, SS, FS, GS) to point to a flat data segment, typically using a selector value like 0x10 for a 32-bit flat descriptor in the GDT; this ensures data access remains valid during the switch. Next, load the GDTR with the base address and size of the GDT using the LGDT instruction, which accepts a 6-byte pseudo-descriptor containing the 32-bit base address (24-bit for 80286) and 16-bit limit. Then, set the PE bit (bit 0) in the CR0 register to 1 using a MOV to CR0 instruction; this action serializes the processor and activates protected mode semantics. Finally, execute a far jump (JMP FAR) to a protected-mode code segment selector (e.g., 0x08 for a 32-bit code descriptor) and offset, which flushes the prefetch queue, reloads CS with the new selector, and begins execution in protected mode. After the jump, reinitialize the remaining segment registers if needed and re-enable interrupts.[12] The Intel 80286 implementation differs from the 80386 in several key aspects during entry. On the 80286, segments are limited to 16-bit operations, and the GDT base is 24 bits wide, requiring a hardware reset to exit protected mode once entered. In contrast, the 80386 supports 32-bit code and data segments (via the D/B flag in descriptors), a full 32-bit GDT base address, and software-based mode switching without reset, allowing larger address spaces and enabling paging if desired post-entry. These enhancements make the 80386 procedure more flexible for modern operating systems.[12] Invalid configurations during entry can trigger exceptions, primarily general protection faults (#GP). For instance, attempting to set the PE bit without a valid GDT or using an invalid segment selector in the far jump causes a #GP(0) exception, halting the processor and requiring error handling via an interrupt service routine if one is already set up. Similarly, loading a null selector into CS or SS post-jump results in a #GP fault. Proper validation of descriptors and selectors is essential to avoid these faults.[12] A minimal assembly code example for entering protected mode on an 80386, assuming a pre-built GDT at physical address 0x1000 with flat 32-bit code (selector 0x08) and data (0x10) segments, illustrates the sequence: cli ; Disable interrupts

lgdt [gdt_descriptor] ; Load GDT (gdt_descriptor at 0x1000-0x1005)

mov eax, cr0

or eax, 1 ; Set PE bit

mov cr0, eax

jmp 0x08:protected_mode ; Far jump to reload CS

protected_mode:

mov ax, 0x10 ; Data segment selector

mov ds, ax

mov es, ax

mov fs, ax

mov gs, ax

mov ss, ax

sti ; Re-enable interrupts

cli ; Disable interrupts

lgdt [gdt_descriptor] ; Load GDT (gdt_descriptor at 0x1000-0x1005)

mov eax, cr0

or eax, 1 ; Set PE bit

mov cr0, eax

jmp 0x08:protected_mode ; Far jump to reload CS

protected_mode:

mov ax, 0x10 ; Data segment selector

mov ds, ax

mov es, ax

mov fs, ax

mov gs, ax

mov ss, ax

sti ; Re-enable interrupts

Exiting Protected Mode

Exiting protected mode on x86 processors, particularly the Intel 80386 and later, involves a careful sequence of operations to return the CPU to real mode while ensuring compatibility with legacy BIOS services and avoiding system instability. This transition disables the protection enable (PE) bit in the CR0 register, flushes the instruction pipeline, and reinitializes segment registers and interrupt handling to mimic the 20-bit addressing and flat memory model of real mode. The procedure requires prior setup of the global descriptor table (GDT) with real-mode-compatible descriptors (64 KB limits, byte granularity) to prevent invalid memory accesses during the switch. The step-by-step procedure for exiting protected mode is as follows: First, disable all interrupts to prevent asynchronous disruptions, including maskable interrupts via the CLI instruction and non-maskable interrupts (NMIs) through external masking or by ensuring a valid real-mode vector for NMI (IVT offset 0x08). Second, if paging is enabled, disable it by clearing the PG bit (bit 31) in CR0, zeroing CR3 to invalidate the page directory, and ensuring the CPU is executing from an identity-mapped physical address to avoid translation errors. Third, clear the PE bit (bit 0) in CR0 using a MOV instruction to disable protected mode addressing and protection checks. Fourth, perform a far jump to a real-mode code segment, typically to offset 0xFFF0 in segment 0xF000 (the conventional BIOS entry point), to flush the prefetch queue and reload the code segment register (CS) with real-mode values. Finally, reload the data segment (DS), extra segment (ES), stack segment (SS), FS, and GS registers with real-mode values (usually 0 for flat addressing), load the interrupt descriptor table register (IDTR) via LIDT to point to the real-mode interrupt vector table (IVT) at physical address 0, and re-enable interrupts with STI. The order of segment register reloads is critical: SS should be updated early to ensure a valid stack for any subsequent operations, followed by DS and ES to avoid data access faults. On the Intel 80386, additional considerations apply for safe exit. Paging must be disabled prior to clearing the PE bit, as active paging with protected mode disabled can lead to unpredictable address translations. In multitasking environments using task state segments (TSS), any active task switch must be completed or aborted by popping the task register (TR) and ensuring no pending task gates in the IDT before the transition, to prevent corruption of the task state.[13] Risks during the exit process include potential triple faults if the GDT is not properly configured with valid real-mode descriptors before clearing PE, as invalid segment references post-transition can trigger unhandled exceptions leading to a double fault and subsequent triple fault, causing a CPU reset. Post-exit, reliance on BIOS calls requires the IVT to be correctly initialized, as improper interrupt handling can hang the system or corrupt memory. This mode-switching capability has been historically utilized in bootloaders like GRUB for hybrid operations, where protected mode is entered for efficient kernel loading but exited to real mode for accessing BIOS disk and video services.[14][15] A representative assembly example for a safe exit on the 80386, assuming paging is disabled and GDT is preset, emphasizes the segment reload sequence: cli ; Disable maskable interrupts

; Assume NMI masked externally

mov eax, cr0

and eax, 0x7FFFFFFE ; Clear PE bit (and PG if needed)

mov cr0, eax

jmp far 0xF000:0xFFF0 ; Far jump to flush pipeline, CS=0xF000, IP=0xFFF0 (BIOS reset vector)

real_mode_cs:

mov ax, 0 ; Real-mode segment value

mov ds, ax ; Reload DS

mov es, ax ; Reload ES

mov ss, ax ; Reload SS (critical for stack)

mov fs, ax ; Reload FS

mov gs, ax ; Reload GS

lidt [real_idt] ; Load IVT pointer (base 0, limit 0x3FF)

sti ; Re-enable interrupts

cli ; Disable maskable interrupts

; Assume NMI masked externally

mov eax, cr0

and eax, 0x7FFFFFFE ; Clear PE bit (and PG if needed)

mov cr0, eax

jmp far 0xF000:0xFFF0 ; Far jump to flush pipeline, CS=0xF000, IP=0xFFF0 (BIOS reset vector)

real_mode_cs:

mov ax, 0 ; Real-mode segment value

mov ds, ax ; Reload DS

mov es, ax ; Reload ES

mov ss, ax ; Reload SS (critical for stack)

mov fs, ax ; Reload FS

mov gs, ax ; Reload GS

lidt [real_idt] ; Load IVT pointer (base 0, limit 0x3FF)

sti ; Re-enable interrupts

Protection Mechanisms

Privilege Levels

Protected mode in the x86 architecture employs a hierarchical privilege system consisting of four rings, numbered 0 through 3, to enforce security boundaries between different software components. Ring 0 represents the highest privilege level, typically reserved for operating system kernel code with unrestricted access to hardware and system resources. Rings 1 and 2 serve as intermediate levels for less trusted system services, such as device drivers or executive modules, while Ring 3 is the lowest privilege level, designated for user applications with restricted access to prevent interference with critical system operations.[12] The privilege of executing code or accessing data is determined by two key fields: the Current Privilege Level (CPL), which indicates the privilege level of the currently running task and is stored in bits 0-1 of the code segment (CS) register, and the Descriptor Privilege Level (DPL), a 2-bit field (bits 5-6 of the access rights byte) in segment descriptors that specifies the minimum privilege required to access the associated segment or gate. The DPL in segment descriptors acts as the primary enforcement mechanism for privilege checks. For nonconforming code segments, code executing at a given CPL can only load segments whose DPL equals the CPL, ensuring same-privilege direct execution. To invoke more privileged code (lower ring number), transitions must occur through controlled mechanisms like call gates, which validate the caller's CPL against the gate's DPL before allowing the switch.[12][3] Data access follows similar rules, where a task at CPL can read or write data segments only if the CPL is less than or equal to the segment's DPL, and the requested privilege level (RPL) of the segment selector is also less than or equal to the DPL; violations result in a general protection fault (#GP). For inter-ring calls to more privileged code using nonconforming segments, the processor performs a stack switch to a new stack segment at the target privilege level, loaded from the task state segment (TSS), and pushes the caller's stack pointer, flags, instruction pointer, and parameters onto it to maintain isolation and enable proper returns. Conforming code segments, marked in their descriptor, allow execution from any CPL greater than or equal to the DPL without a stack switch, facilitating shared library code across privilege levels.[12][3] Input/output (I/O) operations and interrupt handling further enforce privilege separation. I/O instructions from a non-zero ring require the current privilege level to be less than or equal to the I/O privilege level (IOPL) bits in the flags register; otherwise, a #GP fault occurs, with escalation typically to Ring 0 handlers. Interrupts and exceptions always vector to Ring 0 via entries in the interrupt descriptor table (IDT), using interrupt or trap gates that may disable interrupts to prevent nesting issues. In the Intel 80286 implementation, I/O access is strictly limited to Ring 0 unless explicitly permitted via the task's I/O permission bitmap, with no dedicated IOPL field for finer Ring 3 control. The Intel 80386 enhances this by introducing IOPL bits that allow Ring 3 code to perform I/O operations directly if IOPL equals 3, providing more flexible control without always relying on bitmaps. For instance, a Ring 3 application attempting to access a Ring 0 data segment without proper authorization triggers a #GP fault, protecting kernel memory from user-mode corruption.[12][3]Memory Protection Fundamentals

In protected mode, the x86 architecture employs hardware-enforced checks to prevent unauthorized memory access, ensuring isolation between code, data, and tasks. These checks occur automatically during memory operations and include verification of address bounds, access types, and segment or page presence, as defined in memory descriptors. Bounds checking confirms that the effective address falls within the defined limits of the memory region, triggering a fault if exceeded. Type checking validates whether the operation (read, write, or execute) aligns with the region's permissions, such as restricting writes to executable code segments. The present/not-present bit in descriptors further ensures that only loaded or mapped memory regions are accessible, with absent regions causing an immediate fault.[16][3] Violations of these protection rules generate specific exceptions to allow the operating system to handle errors gracefully. The general protection fault (#GP) arises from bounds violations, invalid types, or privilege mismatches, providing an error code identifying the offending selector or operation. The not-present fault (#NP) specifically occurs when a descriptor's present bit is clear, indicating the memory region is not loaded into physical memory. On processors supporting paging, such as the Intel 80386 and later, the page fault (#PF) handles similar issues at the page level, including not-present pages or permission violations, with an error code detailing the cause like writability or user/supervisor access. These faults are fully restartable, enabling precise recovery without data corruption.[16][3] These mechanisms deliver key isolation benefits by enforcing per-task address spaces, where each process operates within its allocated regions without interfering with others. This prevents common exploits like buffer overflows from propagating to adjacent memory areas, enhancing system stability and security. Protection integrates with privilege levels (rings 0-3) to add layered enforcement, where access requires matching current privilege level (CPL) against descriptor privilege level (DPL), further restricting sensitive operations to higher-privilege code. In the Intel 80286, the original implementation of protected mode, these checks relied solely on segmentation for coarse-grained protection without paging support, limiting finer-grained isolation until the 80386's enhancements.[16][3]Memory Management

Segmentation

In protected mode, segmentation provides a mechanism for dividing the linear address space into variable-sized segments, each defined by a segment descriptor stored in either the Global Descriptor Table (GDT) or a Local Descriptor Table (LDT). A segment selector, a 16-bit value loaded into one of the segment registers (CS, DS, ES, FS, GS, or SS), serves as an index into the GDT or LDT to retrieve the descriptor, which specifies the segment's base address, size limit, and access rights such as readability, writability, and executability. The logical address, consisting of the selector and an offset, is translated to a linear address by adding the offset to the segment base; the processor hardware automatically performs bounds checking to ensure the offset does not exceed the segment limit, generating a general-protection exception if it does.[12] This approach contrasts sharply with real mode segmentation, where segments are fixed at 64 KB and addressed via a simple left-shift of the segment value by 4 bits to form a base address, lacking hardware-enforced bounds or access controls. In protected mode, segments can vary in size without the 64 KB restriction, enabling more efficient memory utilization, and stack segments support expand-up (growing from low to high addresses) or expand-down (growing from high to low addresses) configurations to accommodate stack operations while respecting the limit. These features introduce robust protection against buffer overflows and unauthorized access, fundamental to the security model of protected mode.[12] The Intel 80286 implemented protected mode segmentation with 16-bit offsets, restricting each segment to a maximum size of 64 KB, which aligned offsets and addresses within this limit for compatibility with earlier designs but limited scalability for larger programs. The Intel 80386 enhanced this by introducing 32-bit offsets, allowing segments up to 4 GB in size, and added a granularity bit in the descriptor that, when set, scales the limit to units of 4 KB, permitting segment sizes from 4 KB to 4 GB in 4 KB increments for finer control over memory allocation. These improvements made segmentation more practical for multitasking environments and larger address spaces.[12] Segmentation in protected mode supports various segment types essential for program execution and system operation: code segments hold executable instructions with attributes controlling conformity and readability; data segments manage read-write data areas; and stack segments handle push and pop operations with directionality flags. System segments, such as the Task State Segment (TSS), facilitate task management by storing processor state for context switching in multitasking scenarios. This segmented model, while flexible, is often combined with other mechanisms in modern operating systems to address memory needs comprehensively.[12]Paging

The Intel 80386 introduced paging as a key enhancement to its protected mode memory management, providing a mechanism for virtual-to-physical address translation that was absent in the 80286, thereby enabling true virtual memory support for multitasking operating systems.[13] This paging unit operates on 32-bit linear addresses produced by segmentation, dividing the address space into fixed-size pages of 4 KB each, with support for larger 4 MB pages through specific page directory entry flags.[13] Paging employs a two-level hierarchical structure: a Page Directory, which holds up to 1024 entries and serves as the top-level table, points to Page Tables; each Page Table also contains up to 1024 entries that map to individual 4 KB physical pages.[13] The base physical address of the Page Directory is stored in the CR3 control register, allowing dynamic switching of address spaces during task changes.[13] To enable paging, the PG bit (bit 31) in the CR0 register must be set after protected mode is activated (PE bit in CR0), which initiates address translation for all subsequent memory accesses.[13] A 32-bit linear address is split into three fields for translation: the upper 10 bits (31–22) index the Page Directory entry, the middle 10 bits (21–12) index the corresponding Page Table entry, and the lower 12 bits (11–0) provide the offset within the 4 KB page.[13] The translation process begins by using CR3 to locate the Page Directory, then fetches the Page Table base address from the indexed directory entry (shifted left by 12 bits to align to a 4 KB boundary), followed by fetching the physical page frame base from the indexed table entry (also shifted left by 12 bits), and finally adding the offset to yield the physical address.[13] For example, given a linear address of 0x402003, the directory index is 0x001 (bits 31–22), the table index is 0x002 (bits 21–12), and the offset is 0x003 (bits 11–0); the physical address is then computed as ((page frame base from table entry) << 12) + offset.[13] Key features include demand paging, where pages are loaded into physical memory only upon access; this is controlled by the Present bit (P, bit 0) in page directory and table entries—if unset, a page fault exception (#PF) is generated to allow the operating system to handle paging in or out.[13] Page-level protections are enforced via bits in the entries: the Read/Write bit (R/W, bit 1) distinguishes read-only from read-write access, and the User/Supervisor bit (U/S, bit 2) restricts access based on the current privilege level (CPL), with supervisor-mode (U/S=0) pages inaccessible from user mode (CPL>0).[13] Effective permissions combine attributes from both the directory and table entries, providing granular control that complements segmentation.[13] Performance is optimized by a Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB), an on-chip four-way set-associative cache holding 32 recent translations (8 entries per set), which is flushed on CR3 reloads or task switches to ensure coherence.[13] While the 80386 paging supports up to 4 GB of physical memory with 32-bit addresses, later processors introduced Physical Address Extension (PAE) starting with the Pentium Pro to handle more than 4 GB by expanding to 36-bit physical addresses and adding a third level (page directory pointer table) to the hierarchy.[17]Segment Descriptors

Segment descriptors in the Intel 80386 protected mode are 8-byte entries stored in the global descriptor table (GDT) or local descriptor tables (LDT), defining the base address, size, and access attributes of memory segments.[13] Each descriptor consists of a 32-bit base address, a 20-bit limit field, and various control bits for protection and usage.[13] The structure is as follows:| Byte | Bits | Field Name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0-7 | Limit (bits 0-7) | Lower 8 bits of the 20-bit segment limit; when the granularity bit (G) is 0, units are bytes (maximum 1 MB - 1); when G=1, units are 4 KB pages (maximum 4 GB - 1). |

| 1 | 0-7 | Limit (bits 8-15) | Upper 8 bits of the lower 16 bits of the segment limit. |

| 2 | 0-7 | Base (bits 0-7) | Lower 8 bits of the 32-bit base address, specifying the starting linear address of the segment. |

| 3 | 0-7 | Base (bits 8-15) | Next 8 bits of the 32-bit base address. |

| 4 | 0-7 | Base (bits 16-23) | Middle 8 bits of the 32-bit base address. |

| 5 | 0-3 | Type | 4-bit type field defining the segment category and access rights (bits 40-43); combined with S bit for effective 5-bit type interpretation (detailed below). |

| 4 | S (System) | System flag: 0 for system segments, 1 for code/data segments (bit 44). | |

| 5-6 | DPL (Descriptor Privilege Level) | Privilege level (0-3) for the descriptor, used in protection checks; 0 is the most privileged (bits 45-46). | |

| 7 | P (Present) | Present bit: 1 indicates the segment is present in memory; 0 indicates it is not (bit 47). | |

| 6 | 0-3 | Limit (bits 16-19) | Upper 4 bits of the 20-bit segment limit. |

| 4 | AVL (Available) | Available bit for use by system software (bit 52). | |

| 5 | Reserved | Must be 0 (bit 53). | |

| 6 | D/B (Default operation size) | Default size: 0 for 16-bit mode, 1 for 32-bit mode (bit 54). | |

| 7 | G (Granularity) | Granularity bit: 0 for byte granularity, 1 for 4 KB granularity (bit 55). | |

| 7 | 0-7 | Base (bits 24-31) | Upper 8 bits of the 32-bit base address. |