Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pyramid of Khendjer

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

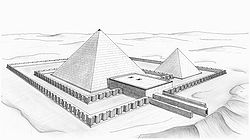

The pyramid of Khendjer was a pyramid built for the burial of the 13th dynasty pharaoh Khendjer, who ruled Egypt c. 1760 BC during the Second Intermediate Period.[2] The pyramid, which is part of larger complex comprising a mortuary temple, a chapel, two enclosure walls and a subsidiary pyramid, originally stood around 37 m (121 ft) high and is now completely ruined.[1] The pyramidion was discovered during excavations under the direction of Gustave Jéquier in 1929, indicating that the pyramid was finished during Khendjer's lifetime.[3] It is the only pyramid known to have been completed during the 13th Dynasty.

Excavations

[edit]The first investigations of the pyramid of Khendjer were undertaken in the mid 19th century by Karl Richard Lepsius, who included the pyramid in his list under the number XLIV. The pyramid was excavated by Gustave Jéquier from 1929 until 1931 with the excavation report published two years later in 1933.[3]

Pyramid complex

[edit]In South Saqqara, the pyramid complex of Khendjer is located between the pyramid of Pepi II and the pyramid of Senusret III. The main pyramid currently lies in ruins, due in part to the damaging excavations by G. Jéquier and now rises only about one meter above the desert sand.[1]

Enclosure walls

[edit]The pyramid complex comprises the main pyramid enclosed by two walls. The outer one, made of mudbrick, contained in the north-east corner a small subsidiary pyramid, the only one known dating to the 13th dynasty. The inner enclosure wall was made of limestone and patterned with niches and panels.[1] This replaced an earlier mudbrick wavy-wall, which led Rainer Stadelmann to suggest that the wavy-wall was constructed as a provisional and abbreviated substitute to the more time consuming but preferred niched-wall. At the south-east corner of the outer wall is a blocked unfinished stairway, which could be part of earlier plans for the pyramid substructure or part of an unfinished south tomb, meant for the Ka of the deceased king.[1]

North chapel

[edit]

A small chapel was built immediately adjacent to the north side of the main pyramid, inside the inner enclosure wall. The chapel was raised on a platform and could be reached by two stairways. The north wall of the chapel housed a yellow quartzite false door. The location of this door was unusual as it should have stood on the wall closest to the pyramid, i.e. the south wall rather than the north one. The few surviving fragments of relief from the chapel show standard scenes with offering bearers.[1]

Mortuary temple

[edit]On the eastern side of the pyramid lay a mortuary temple which spread across both enclosure walls. This allowed for the outer section of the temple to be placed outside the inner wall, with the inner sanctuary on the inside of the inner wall. Very little remains of the temple, except for pieces of reliefs and columns and parts of its pavement.

Main pyramid

[edit]

The pyramid originally stood at 70 royal cubits in height, which is about 37 metres (121 ft).[4] The pyramid was constructed with a mudbrick core and a limestone outer casing with its backing stones. These and the limestone casing were both quarried by stone robbers, which left the core unprotected. The core fared very badly with time and the pyramid now stands only one meter (3.3 feet) tall due to its disintegration.

A fragmented black granite pyramidion was discovered on the east side of the complex and has been restored by G. Jéquier. It is now on display at the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. The pyramidion is decorated by reliefs showing Khendjer making offerings and is inscribed with the prenomen "Userkare" (Strong is the ka of Ra), which is thus known to be a throne name of Khendjer.

The entrance to the substructures is located at the base of the southern end of the pyramid west side. A stairway with 13 steps leads to a chamber housing a large granite portcullis similar to those encountered in the Mazghuna pyramids, also dated from the Middle Kingdom. The portcullis was originally destined to block the way to the burial chamber but was never put into place across the passage. Beyond the portcullis chamber, a further stairway with 39 steps continued down to a closed double-leaf wooden door. Beyond the door is a second portcullis chamber, which was also left open.[1] In turn this leads to a small antechamber and from there on to a further corridor whose access was concealed beneath the paving of the antechamber floor. This corridor leads to the burial chamber.

Khendjer's second portcullis chamber, antechamber and corridor were constructed in the corner of a large trench dug in the ground. The burial chamber, which is made of a colossal monolithic quartzite block, was placed in the trench before the pyramid construction started, in a manner similar to the burial chamber of Amenemhet III at Hawara. The weight of the quartzite block was estimated at 150 tons by G. Jéquier.[3] The block was carved into two compartments destined to receive the king's coffin, canopic chest and funerary goods. Two large quartzite beams weighing 60 tons formed its roof.[4] Once the block and its roof had been put into position, the workers built a gabled roof of limestone beams and a brick vault above it to relieve the weight of the pyramid.[1] The mechanism for closing the vault consisted of sand-filled shafts on which rested the props of the northern ceiling slab. This would be lowered on the vault on draining the sand.[5] After draining all the sand, the workmen escaped through the corridor which they filled with masonry and paved over its opening in the antechamber.

Subsidiary pyramid

[edit]

At the north eastern corner of Khendjer's pyramid complex is a small subsidiary pyramid, which is thought to have been prepared for the burials of two of Khendjer's queens. G. Jéquier also found shaft tombs nearby, which may have been prepared for other royal family members. The entrance to the substructures of this pyramid lie at the base of its eastern base. A small stairway leads to two portcullis chambers similar to those found in the main pyramid. Here too the portcullises were left open. Beyond is an antechamber branching to the north and south to two burial chambers lined with masonry and both housing a large quartzite coffer. The lids of the coffers were found propped on blocks as they should be before any burial. The two coffers were thus most probably never lowered into place and put into use.[1]

Some unexpected turn of events probably prevented their use, although there is nothing directly suggesting that the king wasn't interred as planned in the main pyramid.[6][7] However, in his 1997 study of the Second Intermediate Period, egyptologist Kim Ryholt concludes that Khendjer's successor, Imyremeshaw, usurped the throne.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mark Lehner: The Complete Pyramids. London, 1997, Thames and Hudson Ltd. ISBN 0-500-05084-8

- ^ a b K.S.B. Ryholt, The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period, c.1800–1550 BC, Carsten Niebuhr Institute Publications, vol. 20. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 1997, excerpts available online here.

- ^ a b c Gustave Jéquier: Deux pyramides du Moyen Empire, Cairo 1933, pp. 3-35

- ^ a b Dieter Arnold: The Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture, 2001, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 978-1860644658, excerpt available online.

- ^ Dieter Arnold: Building in Egypt: Pharaonic Stone Masonry, 1997, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195113747, excerpts available online.

- ^ Edwards, Dr. I.E.S.: The Pyramids of Egypt 1986/1947 p. 246-9

- ^ "The Pyramid of Khendjer at South Saqqara in Egypt". www.touregypt.net (in Russian). Retrieved 2018-02-26.

External links

[edit]- The Pyramid Complex of Khendjer

- "Egypt Sites". Pyramid and complex information. Archived from the original on September 4, 2006. Retrieved May 21, 2006.

Pyramid of Khendjer

View on GrokipediaHistorical Context

Reign of Khendjer

Khendjer, whose nomen is interpreted as deriving from the Semitic word ḥanzīr meaning "boar" or "pig," exhibits characteristics suggesting foreign origins, likely from Semitic-speaking regions such as Palestine or Syria.[4] This etymology positions him as one of the earliest rulers in a native Egyptian dynasty with clear Asiatic influences, as noted in analyses of 13th Dynasty nomenclature. His prenomen, Userkare ("The ka of Re is powerful"), appears in royal inscriptions, reinforcing his adoption of traditional Egyptian titulary despite potential non-Egyptian heritage.[5] Khendjer is attested as a king of the 13th Dynasty through several contemporary sources, including a damaged entry in the Turin King List, placing him among the early to mid-13th Dynasty rulers, though the exact sequence remains uncertain due to lacunae in the list.[5][6] Additional confirmations come from scarabs bearing his name and titles, which circulated as seals or amulets during his rule, and from inscriptions within his pyramid complex at Saqqara, including control marks on stone blocks and fragments of reliefs.[7][8] These artifacts collectively place him firmly within the early to mid-sequence of the dynasty's approximately 50-60 kings.[6] His reign is estimated to have lasted a minimum of four years and three months, based on dated control notes from the pyramid construction, though it may have extended slightly longer amid the dynasty's pattern of brief tenures.[5] Placed around 1765–1760 BCE in conventional chronologies, Khendjer's rule occurred during a phase of increasing political fragmentation in the late Middle Kingdom, characterized by weakened central authority and regional rivalries.[9] As one of numerous short-lived pharaohs, he commissioned his pyramid at Saqqara to assert legitimacy and continuity with pharaonic traditions, a project that appears to have advanced significantly during his lifetime.[5]Second Intermediate Period

The Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782–1570 BC) represents a phase of political fragmentation and weakened central authority in ancient Egypt, spanning the 13th to 17th Dynasties and characterized by the rise of regional powers and foreign influences.[10] The 13th Dynasty (c. 1803–1649 BC), often marking the onset of this era, saw a proliferation of short-reigned kings with diminishing control over the Nile Delta, with the royal court shifting southward to Thebes later in the dynasty amid growing challenges to unified governance.[11] This period of instability facilitated the emergence of local rulers and set the stage for Hyksos incursions from the Levant, who established dominance in the north by the mid-17th Dynasty.[12] Pyramid construction during the 13th Dynasty reflected the era's broader decline, with structures shifting to mudbrick cores cased in limestone, resulting in smaller scales and reduced durability compared to the stone monuments of the Old and early Middle Kingdoms.[11] This transition stemmed from resource shortages and economic strain exacerbated by political fragmentation, limiting the state's capacity for large-scale projects and leading to many unfinished royal tombs.[11] Khendjer's pyramid at Saqqara stands as the only known fully completed pyramid from the dynasty, exemplifying a tenuous continuity with earlier pharaonic traditions of monumental burial despite the surrounding instability.[11] The period also witnessed increasing Asiatic elements in Egyptian royal culture, particularly evident in the Semitic origins of Khendjer's name, suggesting early foreign influences that foreshadowed the Hyksos period.[12] These incursions introduced new technologies and cultural exchanges, further eroding traditional Egyptian authority while contributing to the dynasty's eclectic nomenclature.[12]Discovery and Excavations

Early Investigations

The first systematic documentation of the Pyramid of Khendjer occurred during the Prussian expedition to Egypt led by Karl Richard Lepsius between 1842 and 1845. During his survey of Saqqara, Lepsius cataloged the structure as pyramid No. XLIV in his comprehensive list of Egyptian pyramids, noting its location in South Saqqara near other late Middle Kingdom monuments.[13] His team produced drawings and descriptions that highlighted the pyramid's severely eroded form, with much of the original limestone casing stripped away, exposing the underlying mudbrick core and reducing the structure to a low, irregular mound.[13] Early explorers observed the site's ruined condition, attributing the degradation to centuries of natural erosion, stone quarrying, and ancient looting activities that had disturbed the surface layers. The partial exposure of the mudbrick core was particularly evident, as the once-smooth exterior had collapsed in many areas, leaving scattered debris and no intact upper portions visible. These observations were limited to visual inspections and basic measurements, as 19th-century techniques lacked the tools for subsurface probing or preservation. The pyramid's attribution to the 13th Dynasty emerged from its architectural similarities to other Second Intermediate Period structures in the vicinity, such as the nearby unfinished pyramid (Lepsius No. XLVI), and the overall stylistic features of mudbrick construction typical of that era's royal tombs at Saqqara. Proximity to known 13th Dynasty sites reinforced this classification, though no royal name was identified at the time due to the absence of preserved inscriptions on the visible remains. Limitations of these early efforts were significant; without systematic excavation or stratigraphic analysis, records remained superficial, capturing only surface features and omitting subterranean elements or broader contextual relationships. This approach, common to 19th-century Egyptology, prioritized cataloging over in-depth study, leaving many details unresolved until later archaeological work.Jéquier's Excavation

In 1929–1931, Swiss Egyptologist Gustave Jéquier, working under the auspices of the French Archaeological Mission at Saqqara, led the systematic excavation of the Pyramid of Khendjer, marking the first major modern investigation of the site.[5] Employing period-appropriate methods such as manual clearing with picks and baskets, Jéquier's team removed accumulated sand and debris to reveal the pyramid's layout, including its enclosure and subsidiary features, while prioritizing the recovery of architectural elements.[14] This effort built briefly on earlier 19th-century surveys but focused on comprehensive mapping and artifact extraction.[2] A key discovery was the pyramidion, a black granite capstone measuring approximately 141 cm at its base, unearthed in 1929 near the pyramid's apex debris.[15] Cataloged as JE 53045 and currently housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, it bears inscriptions including Khendjer's prenomen Userkare (Wsr-k3-Rˁ), with reliefs on the faces depicting the king alongside deities such as Atum and Re, and a sun disk motif on the eastern face, confirming the monument's completion during his reign.[16] Jéquier also explored the subterranean substructures, documenting a descending corridor leading to an antechamber, burial chamber, and a series of granite portcullises intended to block access to the sarcophagus area.[14] Jéquier's findings were detailed in his 1933 publication Deux pyramides du Moyen Empire: Fouilles à Saqqarah, a seminal volume in the Fouilles à Saqqarah series that includes measured plans, photographic plates, and interpretive sketches of the complex's layout and construction phases.[17] The work emphasized the pyramid's mud-brick core and limestone casing, offering early insights into Second Intermediate Period royal architecture.[14] However, the excavation's reliance on large earthen ramps for debris removal left visible scars on the site, contributing to the erosion of surviving mud-brick elements and complicating later studies.Architectural Complex

Enclosure Walls

The Pyramid of Khendjer's complex was enclosed by a double perimeter wall system, consisting of an outer mudbrick structure and an inner limestone barrier, as uncovered during excavations led by Gustave Jéquier in 1929–1931. The outer wall, built from mudbrick, formed a square enclosure encompassing the main pyramid, subsidiary pyramid in the northeast corner, mortuary temple, and associated features to define the sacred temenos. The inner enclosure wall, constructed of limestone blocks, separated the core ritual areas and featured decorative niches and panels along its facade, enhancing its aesthetic and symbolic role in demarcating the pharaoh's eternal domain. This limestone wall was erected over an initial mudbrick phase that incorporated a wavy or serpentine outline, a design element reminiscent of Middle Kingdom traditions but ultimately abandoned mid-construction, indicating a shift in architectural planning possibly due to resource availability or stylistic preferences during the 13th Dynasty. The redesign reflects adaptive construction practices typical of the Second Intermediate Period, where mudbrick foundations were often overlaid with more durable stone for permanence.[18] The walls served dual purposes of physical protection against intruders and symbolic demarcation of the divine space, isolating the royal cult from profane areas. Post-construction, the enclosures suffered significant damage from later quarrying activities, with much of the mudbrick outer wall dismantled for reusable materials, leaving only fragmentary remnants visible today.North Chapel

The North Chapel of the Pyramid of Khendjer served as a key ritual annex adjacent to the pyramid's north face, positioned on a raised platform that facilitated processional access via two flanking stairways. This design allowed participants in funerary ceremonies to approach the structure directly, emphasizing its role in ongoing cult practices. The chapel extended outward to abut the inner enclosure wall, integrating it into the broader architectural complex while maintaining a distinct focus on northern-oriented rituals.[1][17] Constructed primarily from mudbrick with select limestone components, the chapel reflected practical adaptations common in 13th Dynasty pyramid building, where durable stone was reserved for critical elements. Its most notable interior feature was a yellow quartzite false door set into the north wall, an unusual placement since such portals—symbolizing access for the deceased's spirit—were typically oriented westward toward the underworld. Accompanying this were fragments of reliefs depicting standard offering scenes, suggesting spaces for presenting goods to sustain the pharaoh's ka in the afterlife.[1][17] Extensive ancient robbing has left the chapel in ruins, with only scant evidence remaining of its original form, including traces of a roofed hall likely intended for cult worship or housing a statue of the deified king. These limited archaeological finds, uncovered during Gustave Jéquier's excavations from 1929 to 1931, underscore the chapel's symbolic function as a site for perpetual veneration, distinct from the more elaborate eastern mortuary temple.[17][1]Mortuary Temple

The mortuary temple of the Pyramid of Khendjer was situated on the eastern side of the main pyramid, extending across both the inner and outer enclosure walls to facilitate public access for ritual purposes. This strategic placement integrated the temple into the broader architectural complex, allowing it to function as the central venue for the perpetual worship of the king following his death. The temple's layout spanned the enclosure boundaries, with portions outside the inner wall serving broader ceremonial needs and the inner section reserved for more sacred activities.[1] Archaeological remains of the temple are limited due to extensive plundering and quarrying, but include a limestone pavement, fragmented limestone reliefs illustrating offering scenes, and bases of columns from what appears to have been a hypostyle hall. These elements were uncovered during excavations led by Gustave Jéquier between 1929 and 1931, highlighting the temple's original construction in fine limestone before its systematic dismantling for reusable materials. The relief fragments depict standard mortuary motifs, such as presentations of goods to the deceased king, underscoring the temple's role in sustaining his ka through symbolic and actual offerings.[1][3] Designed to support the eternal cult of Khendjer, the temple incorporated functional spaces such as altars for sacrifices, magazines for storing offerings, and likely niches for housing statues of the king and deities, though these have not survived intact owing to ancient looting. The overall structure was heavily damaged, with much of the limestone reused in later constructions, leaving only scattered architectural debris. In scale, the temple was notably smaller than those of earlier Middle Kingdom rulers, such as those at Lisht or Dahshur, a reflection of the diminished resources and political instability characterizing the 13th Dynasty.[1][19]Main Pyramid

External Structure

The Pyramid of Khendjer was constructed as a true pyramid with a square base measuring 52.5 meters on each side, an original height of 37.35 meters, and a slope angle of 55 degrees, resulting in a volume of approximately 34,315 cubic meters.[5] The structure featured a core built primarily from mudbrick laid in horizontal layers, encased in fine Tura limestone that provided a smooth, polished exterior. This casing was systematically removed in antiquity by stone robbers, exposing the vulnerable mudbrick to the elements. Like other pyramids at Saqqara, the Pyramid of Khendjer was precisely oriented to the cardinal points, with its sides aligned to the north, south, east, and west, reflecting standard Egyptian architectural practices for solar and stellar alignment. Today, the pyramid stands in ruins, reduced to a height of only about 1 meter above the surrounding desert sand, owing to centuries of natural erosion, extensive stone quarrying, and damage from early 20th-century excavations. The remaining core forms a low, eroded mound, with traces of the original foundation visible amid the debris.[5]Subterranean Features

The subterranean features of the Pyramid of Khendjer are accessed via a descending corridor and staircase entering from the southern end of the western face, leading to a portcullis chamber containing quartzite slabs designed for securing the passage but never installed.[17] [1] These chambers served as critical security elements, with the quartzite slabs intended to drop into place to block access once the burial was complete.[17] From the portcullis chamber, the layout proceeds through further corridors to an antechamber that connects directly to the burial chamber, a monolithic structure carved from quartzite and estimated to weigh 150 tons.[17] The burial chamber features a gabled roof constructed of limestone beams, which distributed structural loads effectively to prevent collapse under the pyramid's weight.[17] The chamber included a pit for the sarcophagus and niches for a canopic chest; it was sealed using sand-filled shafts, a technique reminiscent of Amenemhet III's pyramid at Hawara.[1] This design emphasized durability in the underground environment, with the quartzite providing resistance to moisture and intrusion. Excavations by Gustave Jéquier in 1929–1931 revealed no sarcophagus or burial goods within the chamber, strongly suggesting ancient looting had occurred; the corridors were filled with rubble, and the portcullis mechanisms remained partially operational, indicating an attempt to protect the site post-burial.[17] Jéquier noted breaches in the blocking system, consistent with patterns of tomb robbery during the Second Intermediate Period.[17] To address the challenges of Saqqara's unstable bedrock, the corridors were rock-cut and reinforced with mudbrick linings, a practical adaptation that stabilized the passages while minimizing material costs in the mudbrick-dominated core of the pyramid.[17] This technique reflected the era's engineering pragmatism, balancing security with the site's geological constraints.[17]Subsidiary Pyramid

Design and Construction

The subsidiary pyramid of the Khendjer complex is positioned in the northeast corner, between the inner and outer enclosure walls.[5] Its entrance faces east, and the structure is separated from the main pyramid by the inner enclosure wall.[5] The base measures approximately 25.5 meters per side, characteristic of smaller satellite structures in Middle Kingdom pyramid complexes. The substructure features a corridor accessed via a stairway and ramp, secured by two barriers, leading to a central antechamber that branches into two burial chambers—one to the north and one to the south. Each chamber contains a quartzite coffer designed to hold a sarcophagus, but the lids were discovered propped open on adjacent blocks, evidencing that the spaces were prepared yet never utilized for interments. Like many small Middle Kingdom pyramids, the superstructure's original height and casing materials remain uncertain due to extensive robbing of building components.[5] Intended likely for royal consorts or family members, the subsidiary pyramid reflects late Middle Kingdom practices for secondary royal burials, integrated into the overall construction phase of the complex but ultimately left incomplete and unused.Associated Burials

Around the subsidiary pyramid, a cluster of shaft tombs was uncovered during Gustave Jéquier's excavations in 1929–1930, consisting of vertical shafts descending 10 to 15 meters to simple rock-cut chambers designed for multiple interments.[5] These tombs, located within the enclosure walls, featured minimal architectural elaboration, with some shafts partially lined with mud bricks in their upper sections to stabilize the poor-quality bedrock, distinguishing them from the more robust, coffer-equipped burial chambers of the main and subsidiary pyramids.[5] In contrast to the subsidiary pyramid's two unused quartzite coffers, intended possibly for royal consorts but left empty, these shafts lacked such sarcophagi, underscoring their secondary status for non-primary royal burials.[5] The tombs provided evidence of multiple burials, likely belonging to Khendjer's relatives such as queens or high-ranking officials, though ancient plundering had disturbed the sites extensively, leaving no major artifacts or intact remains for Jéquier to recover.[1] Minor finds, including pottery fragments consistent with 13th Dynasty styles, were noted, but the overall poverty of preserved contents reflects the tombs' targeted looting in antiquity.[1] This arrangement of shaft tombs is interpreted as a dedicated family necropolis, extending the pyramid complex's funerary function to accommodate the extended royal household and highlighting the 13th Dynasty's adaptation of earlier pyramid traditions for broader elite interments.[5]Significance and Legacy

Pyramidion and Completion

The pyramidion of the Pyramid of Khendjer is a black granite capstone standing approximately 1.4 m tall, featuring incised reliefs of a scarab beetle and sun disc on the eastern face, the god Osiris on the western face, and royal cartouches on the northern and southern faces. It bears inscriptions with the royal prenomen Userkare ("Strong is the ka of Re"), affirming its association with Khendjer.[16][20] Discovered in fragments during Gustave Jéquier's excavations at South Saqqara in 1929, the pyramidion was found near the pyramid's north chapel, allowing for its reconstruction and providing direct evidence that the structure attained its intended height of approximately 37 m during Khendjer's reign.[2][21] The motifs on the pyramidion incorporate protective spells and solar symbolism, evoking the king's ascent to the afterlife through solar and Osirian associations, a style characteristic of Middle Kingdom traditions but comparatively rare among 13th Dynasty examples.[22] Today, the restored pyramidion is housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, cataloged under inventory number JE 53045.[23]Modern Interpretations

One prominent modern interpretation posits that Khendjer's successor, Imyremeshaw, usurped the throne, which may account for the unused subsidiary coffers in the pyramid complex and evidence of a potentially rushed completion. This theory, proposed by Egyptologist Kim Ryholt in his analysis of Second Intermediate Period chronology, draws on the Turin King List and contemporary inscriptions suggesting political instability and abrupt shifts in rulership during the 13th Dynasty.[24] The usurpation hypothesis underscores how internal power struggles could have interrupted construction, leaving features like the subsidiary structures unutilized despite the main pyramid's completion.[24] Significant gaps persist in the scholarly understanding of the pyramid due to the absence of major excavations since Gustave Jéquier's campaigns from 1929 to 1931, with his 1933 report remaining the primary documentation. Subsequent fieldwork has been limited to surveys, such as a 2006 mapping effort in the surrounding area, but no comprehensive re-excavation has occurred, hindering updated assessments of the site's stratigraphy and artifacts.[25] Additionally, the relief fragments discovered by Jéquier have received minimal post-1933 analysis, and his reports require reanalysis with modern techniques to clarify details like construction phases and iconographic elements.[5] In comparison to other 13th Dynasty pyramids at South Saqqara, such as the unfinished Southern South Saqqara Pyramid attributed to an anonymous ruler, Khendjer's structure stands out as a rare completed monument amid a pattern of abandoned projects reflecting dynastic decline. This outlier status highlights the pyramid's role in illuminating the 13th Dynasty's turbulent end and the transition to the Second Intermediate Period. Modern scholarship also emphasizes potential foreign influences, evidenced by Khendjer's Semitic name (interpreted as ḥanzīr, meaning "boar"), suggesting Asiatic origins that may have subtly impacted architectural choices, though traditional Egyptian forms predominate.[4] The lack of post-1933 fieldwork further limits insights into how such influences contributed to broader cultural shifts during this era.[24]References

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pyramidion_of_Khendjer_1999.jpg