Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

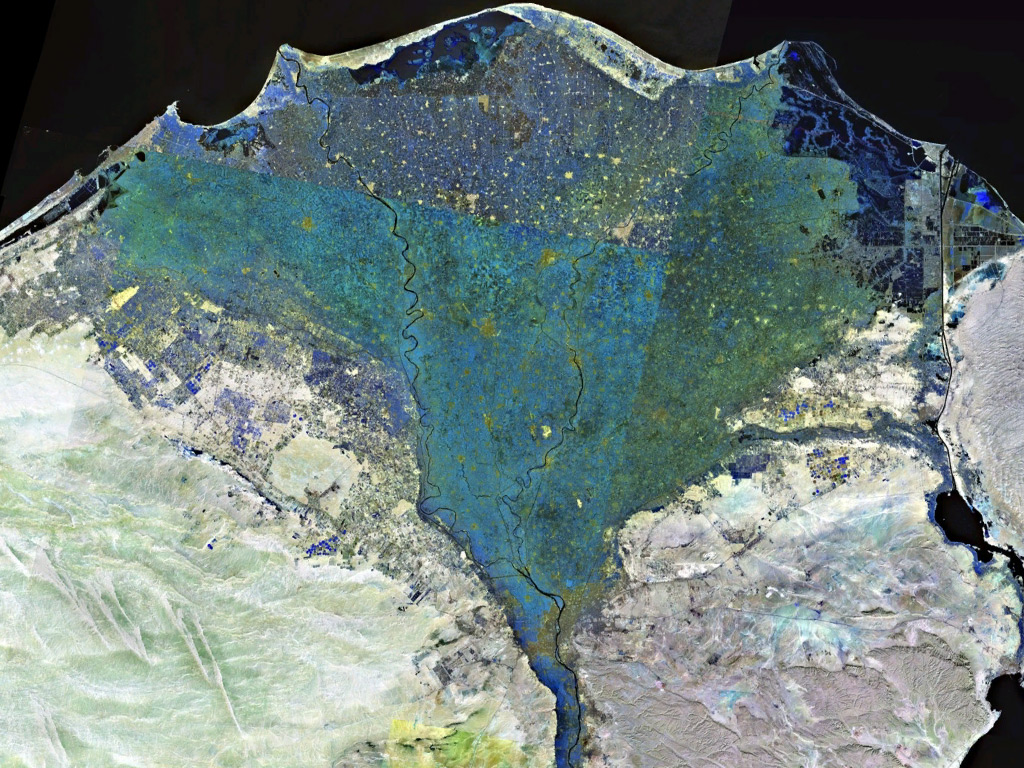

Nile Delta

View on Wikipedia

The Nile Delta (Arabic: دلتا النيل, Delta an-Nīl or simply الدلتا, ad-Delta) is the delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea.[1] It is one of the world's larger deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the east; it covers 240 km (150 mi) of the Mediterranean coastline and is a rich agricultural region.[2] From north to south the delta is approximately 160 km (100 mi) in length. The Delta begins slightly down-river from Cairo.[3]

Geography

[edit]From north to south, the delta is approximately 160 km (100 mi) in length. From west to east, it covers some 240 km (150 mi) of coastline. The delta is sometimes divided into sections, with the Nile dividing into two main distributaries, the Damietta and the Rosetta,[4] flowing into the Mediterranean at port cities with the same names. In the past, the delta had several distributaries, but these have been lost due to flood control, silting and changing relief. One such defunct distributary is Wadi Tumilat.[citation needed]

The Suez Canal is east of the delta and enters the coastal Lake Manzala in the north-east of the delta. To the north-west are three other coastal lakes or lagoons: Lake Burullus, Lake Idku and Lake Mariout.

The Nile is considered to be an "arcuate" delta (arc-shaped), as it resembles a triangle or flower when seen from above. Aristotle speculated that the delta was constructed for agricultural purposes due to the drying of the region of Egypt.[5]

In modern day, the outer edges of the delta are eroding, and some coastal lagoons have seen increasing salinity levels as their connection to the Mediterranean Sea increases. Since the delta no longer receives an annual supply of nutrients and sediments from upstream due to the construction of the Aswan Dam, the soils of the floodplains have become poorer, and large amounts of fertilizers are now used. Topsoil in the delta can be as much as 21 m (70 ft) in depth.[citation needed]

History

[edit]

People have lived in the Nile Delta region for thousands of years, and it has been intensively farmed for at least the past five thousand years. The delta was a major part of Lower Egypt, and many archaeological sites are located in and around the region.[6] Artifacts belonging to ancient sites have been found on the delta's coast. The Rosetta Stone was found in the delta in 1799 in the port city of Rosetta (an anglicized version of the name Rashid). In July 2019 a small Greek temple, ancient granite columns, treasure-carrying ships, and bronze coins from the reign of Ptolemy II, dating back to the third and fourth centuries BC, were found at the sunken city of Heracleion, colloquially known as Egypt's Atlantis. The investigations were conducted by Egyptian and European divers led by the underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio. They also uncovered a devastated historic temple (the city's main temple) underwater off Egypt's north coast.[7][8][9][10]

In January 2019, archaeologists led by Mostafa Waziri working in the Kom Al-Khelgan area of the Nile Delta discovered tombs from the Second Intermediate Period and burials from the Naqada II era. The burial site contained the remains of animals, amulets and scarabs carved from faience, round and oval pots with handles, flint knives, broken and burned pottery. All burials included skulls and skeletons in the bending position and were not very well-preserved.[11][12]

Ancient branches of the Nile

[edit]

Records from ancient times (such as by Ptolemy) reported that the delta had seven distributaries or branches, (from east to west):[4]

- the Pelusiac

- the Tanitic

- the Mendesian

- the Phatnitic or Phatmetic (later the Damietta)

- the Sebennytic

- the Bolbitine (later the Rosetta)[13]

- the Canopic (also called the Herakleotic,[14] Agathodaemon[15])

George of Cyprus list

[edit]Source:[16]

- Alexandrian (Schedia canal)

- Colynthin (Canopic)

- Agnu (Rosetta)

- Parollos (Burullus)

- Chasmatos (Baltim)

- Tamiathe (Damietta)

- Tenese (Tinnis)

Modern Egyptologists suggest that in the Pharaonic era there were at a time five main branches:[17][18]

- the Pelusiac

- the Sebennytic

- the Canopic

- the Damietta

- the Rosetta

The first three have dried up over the centuries due to flood control, silting and changing relief, while the last two still exist today. The Delta used to flood annually, but this ended with the construction of the Aswan Dam.

Population

[edit]

About 39 million people live in the Delta region. Outside of major cities, population density in the delta averages 1,000/km2 (2,600/sq mi) or more. Alexandria is the largest city in the delta with an estimated population of more than 4.5 million. Other large cities in the delta include Shubra El Kheima, Port Said, El Mahalla El Kubra, Mansura, Tanta, and Zagazig.[19]

Wildlife

[edit]

During autumn, parts of the Nile River are red with lotus flowers. The Lower Nile (North) and the Upper Nile (South) have plants that grow in abundance. The Upper Nile plant is the Egyptian lotus, and the Lower Nile plant is the Papyrus Sedge (Cyperus papyrus), although it is not nearly as plentiful as it once was, and is becoming quite rare.[20]

Several hundred thousand water birds spend their winter in the delta, including the world's largest concentrations of little gulls and whiskered terns. Other birds making their homes in the delta include grey herons, Kentish plovers, shovelers, cormorants, egrets and ibises.[citation needed]

Other animals found in the delta include frogs, turtles, tortoises, mongooses, and the Nile monitor. Nile crocodiles and hippopotamus, two animals which were widespread in the delta during antiquity, are no longer found there. Fish found in the delta include the flathead grey mullet and soles.[citation needed]

Climate

[edit]The Delta has a hot desert climate (Köppen: BWh) as the rest of Egypt, but its northernmost part, as is the case with the rest of the northern coast of Egypt which is the wettest region in the country, has relatively moderate temperatures, with highs usually not surpassing 31 °C (88 °F) in the summer. Only 100–200 mm (4–8 in) of rain falls on the delta area during an average year, and most of this falls in the winter months. The delta experiences its hottest temperatures in July and August, with a maximum average of 34 °C (93 °F). Winter temperatures normally range from 9 °C (48 °F) at nights to 19 °C (66 °F) in the daytime. With cooler temperatures and some rain, the Nile Delta region becomes quite humid during the winter months.[21]

Sea level rise

[edit]

Egypt's Mediterranean coastline experiences significant loss of land to the sea, in some places amounting to 90 m (100 yd) a year. The low-lying Nile Delta area in particular is vulnerable to sea level rise associated with global warming.[22] This effect is exacerbated by the lack of sediments being deposited since the construction of the Aswan Dam. If the polar ice caps were to melt, much of the northern delta, including the ancient port city of Alexandria, could disappear under the Mediterranean. A 30 cm (12 in) rise in sea level could affect about 6.6% of the total land cover area in the Nile Delta region. At 1 m (3 ft 3 in) sea level rise, an estimated 887 thousand people could be at risk of flooding and displacement and about 100 km2 (40 sq mi) of vegetation, 16 km2 (10 sq mi) wetland, 402 km2 (160 sq mi) cropland, and 47 km2 (20 sq mi) of urban area land could be destroyed,[23] flooding approximately 450 km2 (170 sq mi).[24] Some areas of the Nile Delta's agricultural land have been rendered saline as a result of sea level rise; farming has been abandoned in some places, while in others sand has been brought in from elsewhere to reduce the effect. In addition to agriculture, the delta's ecosystems and tourist industry could be negatively affected by global warming. Food shortages resulting from climate change could lead to seven million "climate refugees" by the end of the 21st century. Nevertheless, environmental damage to the delta is not currently one of Egypt's priorities.[25]

The delta's coastline has also undergone significant changes in geomorphology as a result of the reclamation of coastal dunes and lagoons to form new agricultural land and fish farms as well as the expansion of coastal urban areas.[26]

Governorates and large cities

[edit]The Nile Delta forms part of these 10 governorates:

Large cities located in the Nile Delta:

References

[edit]- ^ Dumont, Henri J. (6 May 2009). The Nile: Origin, Environments, Limnology and Human Use. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-4020-9726-3.

- ^ Negm, Abdelazim M. (25 May 2017). The Nile Delta. Springer. p. 36. ISBN 978-3-319-56124-0.

- ^ Zeidan, Bakenaz. (2006). The Nile Delta in a global vision. Sharm El-Sheikh., archived from the original on 10 July 2020, retrieved 10 July 2020

- ^ a b John Cooper (30 September 2014). The Medieval Nile: Route, Navigation, and Landscape in Islamic Egypt. The American University in Cairo Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-977-416-614-3.

- ^ Holz, Robert K (1969). Man-made landforms in the Nile delta. American Geographical Society. OCLC 38826202.

- ^ Location of the site, Kafr Hassan Dawood On-Line, with a map of early sites of the delta.

- ^ "Mysterious temple discovered in the ruins of sunken ancient city". www.9news.com.au. 26 July 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ^ History, Laura Geggel 2019-07-29T10:37:58Z (29 July 2019). "Divers Find Remains of Ancient Temple in Sunken Egyptian City". livescience.com. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Santos, Edwin (28 July 2019). "Archaeologists discover a sunken ancient settlement underwater". Nosy Media. Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- ^ EDT, Katherine Hignett On 7/23/19 at 11:06 AM (23 July 2019). "Ancient Egypt: Underwater archaeologists uncover destroyed temple in the sunken city of Heracleion". Newsweek. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "3,500-Year-Old Tombs Unearthed in Egypt's Nile Delta - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org. 24 January 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Ancient tombs and prehistoric burials found in Nile Delta - Ancient Egypt - Heritage". Ahram Online. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ Hayes, W. 'Most Ancient Egypt', p. 87, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 23 (1964), 73–114.

- ^ e.g. at Callisthenes Alexander 1.31.

- ^ e.g. in Ptolemy, Geography.

- ^ Cooper, John Peter (2008). The Medieval Nile: Route, navigation and landscape in Islamic Egypt. p. 34.

- ^ Shaw, Ian; Nicholson, Paul (1995). The Dictionary of Ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press. p. 83.

- ^ Margaret Bunson, Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Infobase Publishing, 2009, ISBN 1438109970, p. 98.

- ^ City Population website, citing Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics Egypt (web), accessed 11 April 1908.

- ^ Beentje, H.J.; Lansdown, R.V. (2018). "Cyperus papyrus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018 e.T164158A120152171. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T164158A120152171.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Nile Delta Facts, 24 April 2017

- ^ "Global Warming Threatens Egypt's Coastlines and the Nile Delta". EcoWorld. 25 September 2009. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ Hasan, Emad; Khan, Sadiq Ibrahim; Hong, Yang (2015). "Investigation of potential sea level rise impact on the Nile Delta, Egypt using digital elevation models". Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 187 (10): 649. Bibcode:2015EMnAs.187..649H. doi:10.1007/s10661-015-4868-9. PMID 26410824. S2CID 207139887.

- ^ "Egypt's Nile Delta falls prey to climate change". 28 January 2010.

- ^ "Egypt fertile Nile Delta falls prey to climate change". Egypt News. 28 January 2010. Archived from the original on 9 February 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ El Banna, Mahmoud M.; Frihy, Omran E. (2009). "Human-induced changes in the geomorphology of the northeastern coast of the Nile delta, Egypt". Geomorphology. 107 (1): 72–78. Bibcode:2009Geomo.107...72E. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2007.06.025.

External links

[edit]Nile Delta.

- "Nile Delta flooded savanna". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Adaptationlearning.net: UN project for managing sea level rise risks in the Nile Delta

- "The Nile Delta". Keyway Bible Study. Archived from the original on 2 August 2010.

Nile Delta

View on GrokipediaThe Nile Delta is the expansive alluvial plain formed where the Nile River divides into multiple distributaries before discharging into the Mediterranean Sea along Egypt's northern coast, encompassing roughly 22,000 square kilometers of fertile land.[1] This fan-shaped region, one of Africa's largest deltas, owes its productivity to millennia of sediment deposition from the Nile, historically renewed by annual floods that enriched the soil with nutrients essential for agriculture.[2] Supporting approximately 40-50 million people—nearly half of Egypt's population—the delta hosts dense urban centers like Alexandria and Cairo's northern suburbs, alongside intensive farming that contributes disproportionately to the nation's food security and economy, with agriculture in the broader Nile system accounting for about 11-14% of GDP and employing a quarter of the workforce.[3][4] Since antiquity, the Nile Delta has been pivotal to human settlement and civilization in Egypt, fostering early farming communities around 7000 BCE through herding transitioning to crop cultivation on its black silt soils, which underpinned the pharaonic economy via staples like wheat, barley, and flax.[5] The region's strategic position facilitated trade and cultural exchange, with ancient cities emerging on elevated mounds amid marshes, though multi-cultural dynamics persisted due to its openness to Mediterranean influences.[6] In modern times, the delta's defining challenges stem from anthropogenic alterations, particularly the Aswan High Dam's interception of over 95% of the Nile's sediment since 1970, exacerbating coastal erosion at rates up to 100 meters per year in some areas, land subsidence from groundwater extraction and soil compaction, and heightened risks from sea-level rise projected to inundate up to 12% of the delta by 2100 under moderate scenarios.[7][8] These factors, compounded by population pressures and climate variability, threaten the delta's sustainability, prompting debates on adaptation strategies like sediment management and coastal defenses amid empirical evidence of accelerating shoreline retreat.[9]

Physical Characteristics

Location and Extent

The Nile Delta occupies northern Egypt, marking the point where the Nile River discharges into the Mediterranean Sea. It begins approximately 20 kilometers north of Cairo and extends northward for about 160 kilometers to the coastline. The delta encompasses an area of roughly 22,000 square kilometers, characterized by its fan-shaped expanse formed by sediment deposition.[10][11] The delta's coastline measures approximately 240 kilometers, stretching from near Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the east. It is bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, the Suez Canal to the east—which separates it from the Sinai Peninsula—the Nile Valley to the south, and the Western Desert to the west. These boundaries delineate the delta's position within Egypt's physiographic regions, isolating it from the surrounding arid landscapes.[12][13][14] At its apex near Cairo, the Nile bifurcates into two primary distributaries: the western Rosetta Branch (Rashid) and the eastern Damietta Branch (Damiyat), which diverge over 140 kilometers by the time they reach the sea. This branching defines the delta's longitudinal extent and contributes to its triangular outline visible from space.[15][16]Topography and Hydrology

The Nile Delta exhibits a predominantly flat, low-lying topography, with surface elevations generally ranging from sea level at the coast to about 18 meters above sea level in the interior regions.[17] This gentle gradient facilitates extensive agricultural plains but also renders the area susceptible to inundation and subsidence. Key landscape features include expansive marshes, shallow coastal lakes such as Lake Idku, Lake Burullus, and Lake Manzala, and areas of reclaimed land converted for cultivation through drainage and embankment projects.[18][19] Hydrologically, the delta is shaped by the Nile River's bifurcation into two primary distributaries: the Rosetta Branch to the west and the Damietta Branch to the east, which together convey the bulk of the river's discharge to the [Mediterranean Sea](/page/Mediterranean Sea).[20] Post-construction of the Aswan High Dam in 1970, these channels receive regulated flows averaging around 55 cubic kilometers annually, with the dam's impoundment eliminating the natural seasonal flooding that previously replenished aquifers and surface waters.[21][22] This shift has reduced sediment delivery and altered subsurface hydrology, leading to decreased natural recharge of groundwater systems and increased reliance on artificial irrigation.[20] An intricate network of canals supplements the natural channels, supporting irrigation and drainage across the delta's farmlands. The Mahmoudiya Canal, extending from the Nile near Cairo to Alexandria, exemplifies this infrastructure, diverting water for agricultural use and urban supply while aiding navigation.[23] These engineered waterways, combined with the controlled river releases, maintain the delta's water balance but have intensified salinization risks in coastal zones due to diminished freshwater flushing.[24]Formation and Sedimentation Processes

The modern Nile Delta formed primarily during the Holocene epoch, approximately 5,000 to 7,000 years ago, as post-glacial sea-level rise stabilized around 6,000 years before present, allowing fluvial sediments to prograde seaward and build the subaerial delta plain.[25] This accumulation occurred through repeated cycles of sediment deposition during high Nile discharges, sourced predominantly from the Ethiopian Highlands via the Blue Nile and Atbara tributaries, which drain volcanic terrains rich in fine silts, clays, and mafic minerals like pyroxenes.[26] These upstream regions, influenced by seasonal monsoon rainfall, erode basaltic soils and transport weathered material northward over distances exceeding 1,500 kilometers, with lesser contributions from East African rift lakes and Sudanese wadis.[27] Prior to the construction of large dams in the 20th century, the Nile's annual sediment load averaged 140 ± 20 million metric tons, with the Blue Nile alone supplying about 61% of this volume, fostering rapid deltaic growth at rates of up to 1-2 meters per year in prograding lobes.[28] Sedimentation processes are governed by the deceleration of river flow upon entering the broader delta front and Mediterranean Sea, where reduced velocities—dropping from over 1 meter per second in the main channel to near-zero offshore—enable density-driven settling of suspended loads; coarser sands deposit proximal to distributary mouths as mouth bars, while finer silts and clays flocculate and settle via gravitational forces in hypopycnal plumes.[29] This differential deposition creates vertically fining sequences, with Holocene strata dominated by overbank silts forming the fertile alluvial soils that characterize the delta's 22,000 square kilometers.[30] The delta's characteristic arcuate shape results from the interplay of fluvial progradation and marine reworking, where wave-dominated conditions and prevailing westerly longshore currents redistribute eastward-transported sediments along the coast, smoothing the outline and preventing pronounced lobate extensions.[29] Progradation advances the shoreline through subaqueous clinoform development, with sediment bypassing the shelf during flood peaks to form deeper turbidite fans, but the bulk (~80%) accumulates nearshore due to wave-induced resuspension and alongshore transport balancing erosional forces.[31] Over millennia, this dynamic equilibrium has sustained the delta's convex curvature, contrasting with more river-dominated systems, as evidenced by seismic profiles revealing stacked parasequences of regressive deposits.[32]Climate

Regional Climate Patterns

The Nile Delta lies within a Mediterranean climatic regime, featuring hot, arid summers and mild winters with limited but seasonal precipitation. Average summer temperatures in coastal areas like Alexandria reach highs of 30–35°C (86–95°F) from June to September, while winter lows typically range from 10–15°C (50–59°F) between December and February, with daytime highs around 18–20°C (64–68°F).[33][34] Annual precipitation averages 150–200 mm, predominantly occurring during winter months from October to March due to Mediterranean cyclones, with negligible rainfall in summer. Meteorological records from Alexandria indicate low interannual variability in these patterns, with standard deviations in annual rainfall under 50 mm over multi-decadal periods. Prevailing northerly to northwesterly winds dominate throughout the year, driven by the subtropical high-pressure system over the Mediterranean, maintaining relatively stable coastal conditions and contributing to high aridity despite proximity to the sea.[35] Occasional khamsin events—hot, dry southerly winds originating from the Sahara—occur mainly in spring (March–May), elevating temperatures temporarily by 5–10°C and increasing dust transport.[36] These winds, combined with intense solar radiation and low humidity, result in potential evaporation rates exceeding 2,000 mm per year across the delta, as measured by pan evaporation data from regional stations, far outpacing precipitation and underscoring the region's water deficit.[37]Historical and Recent Variability

Historical records of Nile River levels, documented through nilometers such as the Roda gauge in Cairo since A.D. 622, reveal pronounced variability in flood heights, with over 1,700 annual readings of low- and high-water levels indicating decadal periodicities linked to fluctuations in Ethiopian monsoon rainfall.[38] [39] These data show episodes of persistently low floods from A.D. 930–1070 and 1180–1350, interspersed with high-discharge periods, driven primarily by natural variability in the Blue Nile's catchment precipitation rather than a unidirectional trend toward warming.[40] Spectral analysis of these extended records (A.D. 622–1922) confirms oscillatory modes on interannual to multi-decadal scales, consistent with influences from large-scale atmospheric patterns including the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which accounts for approximately 25% of the natural variability in annual Nile flow.[41] [42] In the 20th century, instrumental observations in the Nile Delta indicate a modest warming trend, with annual mean temperatures rising by roughly 1°C from 1900 to 2010, alongside increases in minimum temperatures at rates of 0.02–0.03°C per year in early sub-periods.[43] [44] Precipitation in the region, characterized by its aridity and reliance on upstream Nile inflows rather than local rainfall, has shown relative stability, with no monotonic decline or increase disrupting the historical pattern of erratic monsoon-driven variability.[45] This persistence underscores that Delta climate fluctuations remain predominantly modulated by remote forcings, such as ENSO-modulated summer monsoons in the Ethiopian Highlands, rather than localized anthropogenic signals.[46] [47] Recent events, such as the 2025 Nile surges affecting Egypt and Sudan, exemplify this dynamic, stemming from heavy seasonal monsoon rains in upstream basins peaking in July–August, which elevated river levels independently of Delta-local conditions or dam management disputes.[48] [49] These inflows highlight the continued dominance of natural hydrological cycles over any emergent monotonic shifts, with flood variability paced by interannual mechanisms akin to those evident in medieval records.[50]Ecology and Biodiversity

Flora and Fauna

The flora of the Nile Delta primarily consists of aquatic and semi-aquatic vegetation adapted to its wetland environments, including extensive papyrus (Cyperus papyrus) marshes in freshwater zones and salt-tolerant halophytes such as species in the genus Zygophyllum in coastal saline areas.[51][52] The region encompasses the Nile Delta flooded savanna ecoregion, characterized by flooded grasslands that support diverse herbaceous plants, though much of the natural habitat has been converted to agriculture dominated by crops like cotton and rice.[53] Two plant species are endemic to the Nile Delta: Sonchus macrocarpus and Zygophyllum aegyptium, the latter restricted to Egypt and adjacent regions.[52] Faunal diversity in the Nile Delta is concentrated in its wetlands and coastal lagoons, with over 100 fish species inhabiting the rivers and lakes, including the predatory Nile perch (Lates niloticus) and the cichlid Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus).[54] Reptiles include the Nile monitor lizard (Varanus niloticus), various turtles such as the endangered loggerhead (Caretta caretta) and green turtles (Chelonia mydas) that nest along the coast, and an endemic frog species restricted to the delta.[53] Mammals are limited, featuring species like the Egyptian mongoose (Herpestes ichneumon) and red fox (Vulpes vulpes), adapted to riparian and marshy habitats. The delta's wetlands serve as a critical stopover for migratory birds along the East African-Eurasian flyway, hosting thousands of wintering individuals from over 300 species, including the white stork (Ciconia ciconia), great white pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus), and short-toed snake-eagle (Circaetus gallicus).[55][56] Five Ramsar-designated wetland sites in the Nile Delta, such as Lake Burullus and Lake Manzala, collectively cover approximately 250,000 hectares and provide essential habitats for these avian populations as well as resident waterfowl.[57][58]Ecosystem Services and Threats

The wetlands in the Nile Delta provide essential regulating ecosystem services, including water purification through natural filtration processes that remove nutrients and pollutants from agricultural runoff and wastewater. These wetlands also contribute to flood regulation by absorbing excess water during peak flows, though this capacity has diminished with hydrological alterations. Provisioning services encompass fisheries from the Delta's coastal lakes (such as Idku, Burullus, and Manzala), which historically supported substantial yields; for instance, these lakes produced about 140,000 tons of fish annually around 2001, representing roughly 60% of Egypt's inland capture fisheries at the time. Additionally, the Delta's alluvial soils, enriched by long-term sedimentation, underpin approximately 60% of Egypt's food production, enabling intensive cultivation of crops like rice, cotton, and wheat that form the backbone of national agriculture.[59][60][61] Major threats to these services include habitat loss from land reclamation and urbanization, with approximately 30% of the Delta's waterways landfilled or degraded over recent decades to expand agriculture and settlements. Overfishing in lakes and coastal zones has depleted key species, exacerbating declines in wild stocks amid rising demand. Industrial and agricultural pollution introduces heavy metals and excess nutrients, contaminating sediments and water bodies; for example, wastewater discharges have led to widespread eutrophication and toxic accumulation in Delta lagoons. These pressures compound the impacts of reduced freshwater inflows, further straining wetland functionality and biodiversity.[62][63][64] Empirical evidence highlights the Aswan High Dam's role in fishery degradation: completed in 1965, it trapped sediments and nutrients upstream, slashing the annual flux of nitrogen and phosphorus to the Delta by over 90%, which triggered a collapse in the offshore Mediterranean fishery from pre-dam averages of 35,000–40,000 tons to about 20,000 tons per year. This nutrient deprivation directly curtailed primary productivity in coastal waters, independent of climatic variations, though partial recovery has occurred via anthropogenic inputs like fertilizer runoff. Such causal links underscore how infrastructure-induced changes, rather than transient weather patterns, drive observable ecosystem shifts in the region.[20][65][66]Geological and Historical Evolution

Geological Formation

The modern Nile Delta formed primarily through the interplay of tectonic subsidence, fluvial sediment supply from the Nile River, and eustatic sea-level changes during the Quaternary, with the bulk of its deposition occurring in the Holocene epoch. Following the Last Glacial Maximum around 20,000 years ago, rapid post-glacial sea-level rise flooded the northern Egyptian continental shelf, transitioning to a deceleration phase by approximately 8,000–7,000 years before present that enabled initial deltaic aggradation and progradation.[67] [68] This stabilization allowed Nile-derived sediments—predominantly silts, clays, and sands—to accumulate atop older Pleistocene and Miocene substrates, marking the onset of the delta's arcuate shape.[30] Accelerated buildup occurred during mid-Holocene relative sea-level highstands around 6,000–5,000 years before present, when reduced rates of rise relative to sediment input promoted seaward advance. Seismic reflection profiles and sediment core analyses document historical progradation rates of 1–5 km per century, with the delta extending up to 50 km northward over the past 5,000 years in key sectors, driven by peak Nile discharges exceeding 100 billion cubic meters annually during wetter climatic phases.[69] [70] These rates reflect causal dominance of high sediment flux over tectonic and isostatic factors, as evidenced by isochrone mapping in geophysical surveys.[71] Subsurface structure comprises compacted deltaic sequences of interbedded clays, silts, and sands overlying thicker pre-Holocene fills, with total sedimentary thickness varying from 3–4 km along the shelf to over 10 km in depocenters due to prolonged basin subsidence.[72] [73] Regional tectonics, including reactivation of Precambrian basement faults and development of north-dipping step faults, have segmented the subsurface into horsts and grabens, influencing differential compaction and localized fault throws of hundreds of meters.[7] [74] Core samples confirm these lithologies exhibit high porosity reduction under burial, contributing to ongoing subsidence rates of 1–2 mm per year in uncompacted Holocene layers.[75]Changes in River Channels

The Nile Delta's river channels have undergone multiple avulsions and abandonments throughout history, with ancient accounts documenting a network of distributaries that has since consolidated. In the 5th century BCE, Herodotus described the delta as divided into several branches, including the eastern Pelusiac (the most significant for trade and military access to the Levant) and the western Canopic (a major waterway supporting ports like Herakleion and Canopus).[76] By the 6th–7th century CE, George of Cyprus mapped persisting branches such as the Canopic (Colynthin), Rosetta precursor (Agnu), and Damietta precursor (Tamiathe), reflecting ongoing but reduced multiplicity.[77] Most intermediate branches, including the Tanitic, Mendesian, and Bolbitine, had silted up or shifted by the Roman era (1st century BCE–4th century CE), due to progressive sediment infilling that rendered them non-navigable.[78] The Pelusiac branch, for instance, was largely abandoned by the early Roman period, with its mouth prograding eastward before silting over completely by the 1st century CE.[79] During the Holocene, channel shifts were driven by high sediment aggradation rates exceeding 10 mm/year in distributary channels, leading to superelevation above adjacent floodplains and promoting avulsions toward lower topographic gradients.[70] Tectonic subsidence, averaging 1–2 mm/year in the delta plain due to isostatic adjustment and faulting along the Pelusium Fault Zone, exacerbated these instabilities by creating relative base-level falls that favored seaward channel migration.[80] Avulsions clustered in the mid-Holocene (ca. 6,000–4,000 years BP), transitioning from broad crevassing to more confined, incised channels as sea-level stabilization reduced accommodation space.[81] By late Holocene (post-4,000 years BP), the system stabilized into fewer active branches, with the Canopic persisting until ca. 5th century CE before abandonment via siltation.[82] The two modern branches, Rosetta (Rashid) and Damietta (Dumyat), emerged as dominant by the medieval period and have been artificially stabilized since the 19th–20th centuries through barrages like the Edfina Barrage (built 1953 on Rosetta) and the Damietta Barrage, which regulate flow and prevent upstream avulsion by maintaining channel capacity amid reduced sediment loads.[83] Paleogeographic evidence confirms buried channels: satellite-based spectral-temporal metrics from Landsat archives detect soil moisture and vegetation anomalies tracing relict Pelusiac and Canopic paths under cultivated fields, while Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) data reveal sinuous depressions up to 4 m deep marking the Canopic's former course west of Idku Lagoon.[84][85] These techniques, corroborated by sediment cores showing fluvial sands overlain by deltaic muds dated to 3rd century BCE–5th century CE, underscore how avulsions reorganized the delta's hydrology without modern interventions.[82]Ancient and Historical Human Interactions

Human settlement in the Nile Delta dates to the Neolithic period around 5000 BCE, with early agricultural communities exploiting the region's seasonal flooding for basin irrigation systems. Ancient Egyptians constructed earthen dikes and basins to retain floodwaters, augmented by short distribution canals that directed water into fields, enabling the cultivation of staples such as emmer wheat, barley, and flax across the delta's alluvial soils. These modifications, evident from Predynastic times (c. 4000–3100 BCE) and formalized during the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE), transformed marshy areas into productive farmlands, supporting population densities that underpinned early state formation, though true perennial canal irrigation remained limited until the 19th century.[86] In 331 BCE, Alexander the Great founded Alexandria at the western extremity of the Nile Delta, selecting a site near the extinct Canopic branch for its natural harbor and strategic access to Mediterranean trade routes. The city's development under the Ptolemaic dynasty involved harbor engineering to combat silting from delta sediments, fostering a cosmopolitan center that integrated Greek, Egyptian, and Levantine influences while serving as Egypt's primary port for grain exports.[87] This settlement marked a pivotal engineering adaptation, as ongoing dredging and breakwaters were required to maintain navigability amid the delta's dynamic sedimentation processes.[88] Medieval and Ottoman-era records document recurrent silting of delta branches, such as the Rosetta and Damietta, which reduced navigable waterways and irrigation efficiency, necessitating periodic dredging and canal realignments, particularly in the western Buhayra province from the 16th to 18th centuries. By the 19th century, these challenges prompted large-scale interventions, including the construction of barrages across the principal branches to regulate flow and enable year-round irrigation, shifting from flood-dependent basin methods to perennial systems that boosted cotton production under Muhammad Ali's reforms.[89] The Aswan Low Dam, completed in 1902, further exemplified these feats by impounding water for upstream regulation but acting as an initial sediment trap, curtailing the natural deposition that had sustained delta progradation and soil fertility for millennia.[90] This engineering success causally initiated long-term delta erosion by depriving downstream reaches of vital silt, presaging amplified effects from subsequent dams.[91]Human Geography and Demographics

Population Density and Distribution

The Nile Delta supports an estimated 50 million residents as of 2023, representing nearly half of Egypt's total population of approximately 110 million, despite encompassing only about 2% of the nation's land area.[3][92] This concentration results in average population densities exceeding 1,000 persons per square kilometer, with rural areas often surpassing this figure and certain locales reaching several thousand per square kilometer.[93][94] Population growth in the Delta mirrors Egypt's broader demographic surge, from roughly 27 million nationwide in 1960 to over 110 million in 2023, fueled primarily by high fertility rates historically averaging above replacement levels and the sustained viability of agriculture-dependent settlements.[95][96] The region's share has remained disproportionately high, with census data indicating that Lower Egypt governorates—constituting the Delta—host dense rural populations, particularly in central areas like Gharbia and Dakahlia.[97] Settlement patterns blend extensive rural villages with emerging urban clusters, though increasing soil salinization from seawater intrusion and reduced freshwater flows has driven rural-to-urban migration, exacerbating densities in peri-urban zones while depopulating some marginal farmlands.[3][98] This internal redistribution reflects adaptive responses to environmental degradation, with CAPMAS statistics underscoring accelerated urban growth amid overall regional expansion.[99]Major Cities and Governorates

The Nile Delta spans seven governorates: Alexandria, Beheira, Kafr El-Sheikh, Gharbia, Menufia, Dakahlia, and Damietta.[100] These administrative divisions oversee densely settled coastal and inland areas, with Alexandria functioning as the western anchor and a major Mediterranean port city with a metropolitan population exceeding 5.5 million in 2023.[101] Inland, Mansoura in Dakahlia Governorate serves as a central hub for regional administration and commerce, while Tanta in Gharbia Governorate acts as a focal point for local governance and markets.[102] Key infrastructure includes the ports at Damietta and Rosetta (Rashid), which support maritime access along the delta's eastern and western distributaries. Damietta Port, in particular, manages over 1.7 million twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) annually, contributing significantly to regional logistics.[103] Urban growth across these governorates has encroached on agricultural land, with nearly 10% of arable areas in the Nile Valley and Delta converted to built-up zones since the 1990s, driven by informal settlements and infrastructure demands.[104] This expansion, documented through remote sensing, totals over 74,000 hectares of fertile delta soils lost between the early 1990s and mid-2010s.[105]Economic Significance

Agriculture and Irrigation

The Nile Delta's agricultural sector accounts for approximately 60% of Egypt's food production, primarily through cultivation on fertile black silt soils deposited historically by the Nile.[106] Key crops include rice, wheat, and cotton in rotation with maize and berseem clover, enabling multiple harvests per year under irrigated conditions.[107] Yields for these staples have been sustained and enhanced since the completion of the Aswan High Dam in 1970, which eliminated annual floods but allowed year-round perennial irrigation via controlled water releases, supporting crop cycles that previously depended on seasonal inundation.[108] Irrigation in the Delta transitioned from traditional basin systems—reliant on Nile floods for soil replenishment and watering—to perennial systems beginning in the late 19th century with the construction of barrages and accelerating post-Aswan Dam. This shift utilizes a dense network of approximately 40,000 km of canals and drains to distribute water across 2.5 million hectares of arable land.[109] Water is diverted from the Nile main stem into primary canals, then secondary and tertiary channels, enabling precise allocation for summer crops like rice and cotton, which require flooding or furrow methods, and winter crops like wheat, often grown under basin or sprinkler supplementation.[110] Despite these advancements, irrigation efficiency remains low, with field application rates typically ranging from 50% to 60% due to substantial losses from evaporation, seepage, and over-application in open canals and fields.[111] Controlled releases from Lake Nasser, averaging 55 km³ annually for irrigation, have empirically stabilized productivity since the 1960s by mimicking flood volumes without silt deposition, averting pre-dam variability while facilitating double or triple cropping on the same land.[20] Modernization efforts, including lined canals and drip systems in pilot areas, aim to reduce these inefficiencies, though widespread adoption is limited by infrastructure costs and farmer practices.[112]Industry and Natural Resources

The Nile Delta region encompasses several significant natural gas fields, including the West Nile Delta (WND) project operated by BP, which features developments in the North Alexandria and West Mediterranean Deepwater concessions.[113] Production from WND is projected to reach up to 1.2 billion cubic feet per day (bcf/d), accounting for approximately 25% of Egypt's total natural gas output at peak capacity.[113] Other key fields in the area, such as Nooros onshore and offshore northeast of Alexandria, contribute additional volumes, with Nooros producing from shallow-water reservoirs in the Nile Delta basin.[114] In fiscal year 2018/19, the broader Nile Delta petroleum sector, dominated by gas, yielded about 89.5 million barrels equivalent, representing 16% of Egypt's national total, though gas-specific shares have grown with offshore expansions.[115] Recent extractive activities include the integration of the Sparrow West-1 well into production systems, adding an estimated 40 million cubic feet per day (mcf/d) from onshore Nile Delta reservoirs.[116] Natural gas from these fields supports downstream processing, including facilities near Alexandria that handle gas treatment and feed into Egypt's petrochemical sector, where output is processed for domestic energy and export-oriented industries.[117] The Mediterranean Sea and Nile Delta combined account for around 83% of Egypt's natural gas production, underscoring the region's dominance in the country's hydrocarbon endowment.[118] Fisheries represent another key natural resource, with the Delta's coastal and lacustrine systems supporting both wild capture and aquaculture. The region's lakes, including those in the northern Delta, yield over 36% of Egypt's annual wild fish landings, primarily through traditional netting in brackish waters.[119] Aquaculture ponds covering approximately 8,000 hectares in the Delta contribute more than half of Egypt's total farmed fish production, focusing on species like tilapia, mullet, seabass, and perch adapted to estuarine conditions.[120] These activities leverage the Delta's nutrient-rich outflows but face pressures from habitat alteration and overexploitation.[121]Recent Infrastructure Developments

In June 2025, Egypt announced plans to construct a new desert city west of Cairo, rerouting approximately 7% of the country's annual Nile River water quota—equivalent to about 4 billion cubic meters—from fertile Nile Delta lands to irrigate expansive desert areas.[122] This initiative forms part of the broader New Delta project, launched in the early 2020s, which targets the reclamation of 2.2 million feddans (roughly 9,200 square kilometers) of arid land adjacent to the Delta through new irrigation canals, pumping stations, and wastewater treatment systems.[123] The project employs a combination of Nile surface water and treated drainage to expand agricultural output, aiming to produce export crops and reduce dependency on the densely populated Delta's finite arable zones amid a national population surpassing 110 million.[124] Complementing agricultural expansions, energy infrastructure in the Nile Delta advanced in 2025 with the announcement of two onshore natural gas discoveries—the first in the region since 2023—by Harbour Energy and United Oil and Gas in October.[125] These finds, located in development leases, are expected to bolster domestic production through subsequent appraisal and development wells, supporting Egypt's goal of drilling around 480 exploration wells nationwide over five years with investments exceeding $5.7 billion.[126] Separately, BP secured agreements in September 2025 to drill five new gas wells in the Mediterranean offshore concessions adjacent to the Delta, with operations slated to begin in 2026 at depths of 300 to 1,500 meters.[127] Early October 2025 Nile water surges, which flooded Delta farmlands and villages in northern provinces, prompted accelerated implementation of adaptive infrastructure, including enhanced drainage networks and removal of river encroachments to mitigate inundation risks.[48] In parallel, Egypt advanced desalination capacity, with Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouly announcing targets for 10 million cubic meters of daily desalinated water production by late 2025 to diversify supplies and buffer against flow variability.[128] These measures collectively address escalating demands from population growth and urbanization, shifting water-intensive activities westward to preserve Delta sustainability.[129]Environmental Challenges

Sediment Deprivation from Upstream Dams

The Aswan High Dam, operational since 1970, traps approximately 98% of the Nile River's sediment load, reducing the annual flux from roughly 100 million metric tons to near zero downstream.[130][131] This near-complete retention occurs in Lake Nasser, where sediments accumulate at rates exceeding 1 meter per year in upstream sections, preventing their transport to the delta plain.[132] Prior to the dam, the Nile's flood regime delivered 60-180 million tons of silt annually, fostering delta progradation through deposition that counterbalanced erosional forces.[133] The withheld sediment previously contributed to an average annual topsoil renewal of 1-2 centimeters across the delta's cultivated lands, sustaining agricultural productivity by replenishing nutrients and maintaining soil elevation.[134] Post-dam, this replenishment ceased, shifting the delta from net aggradation to degradation, as the absence of fluvial input allows autogenic compaction and marine processes to dominate without compensatory buildup. Empirical measurements confirm a sediment deficit equivalent to the pre-dam load, with coastal zones experiencing erosion rates of 10-100 meters per year, particularly at the Rosetta and Damietta promontories.[135][136] Bathymetric surveys of the inner shelf reveal widespread scour, with sediment volume losses up to 6 meters in depth along transects near the distributary mouths between 1978 and 1990, indicating active offshore removal by currents and waves in the absence of riverine supply.[137] This deprivation equates to a net annual loss of 50-100 million tons through longshore drift and wave reworking, accelerating shoreline recession without upstream mitigation.[130][138]Land Subsidence and Aquifer Depletion

Land subsidence in the Nile Delta primarily results from the compaction of aquifers due to excessive groundwater extraction, driven by agricultural irrigation demands and urban water needs in densely populated areas. Satellite interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) observations, initiated in the 1990s and continued with missions like Envisat and Sentinel-1, have quantified subsidence rates ranging from 1 to 10 mm per year across the delta, with localized peaks exceeding 20 mm per year in reclaimed lands and near major cities such as Tanta, Mansoura, and Zagazig.[75] These rates stem from the irreversible consolidation of compressible Holocene sediments in overexploited aquifers, where pore water withdrawal reduces support, leading to permanent ground lowering.[75] Delta-wide averages from recent InSAR analyses (2015–2020) indicate subsidence of approximately 2–5 mm per year, often surpassing global sea-level rise rates of about 3 mm per year and amplifying relative coastal vulnerabilities.[139] In the northern delta, rates average around 2.4 mm per year, escalating to 7–17 mm per year in eastern governorates like Ad Dakahlia and Al Sharkia, where intensive pumping for irrigation has depleted shallow aquifers.[139][75] Aquifer depletion is exacerbated by reduced natural recharge, as extraction rates outpace replenishment, causing water table declines of several meters in central and western delta regions over the past two decades. Near Alexandria, InSAR and GPS data from 2003–2010 record subsidence rates of 0.4–2 mm per year on average, with cumulative lowering estimated at 5–20 cm in urban zones since 2000, linked to localized overpumping and sediment compaction beneath expanding infrastructure.[140] Higher rates, up to 4–5 mm per year, occur in inland areas like Tanta and Mahalla al-Kubra, directly attributable to groundwater abstraction for cotton and rice cultivation, which accounts for over 80% of delta water use.[9] These patterns highlight anthropogenic drivers over natural tectonic subsidence, with peer-reviewed modeling confirming that sustained extraction could induce additional 30–90 mm of subsidence under current recharge deficits.[141]Coastal Erosion and Seawater Intrusion

The Nile Delta's Mediterranean coastline has undergone pronounced erosion primarily due to the sharp decline in sediment delivery following the construction of the Aswan High Dam in 1964, which trapped over 95% of the river's annual sediment load upstream. Pre-dam observations indicate relative stability or localized progradation, but post-dam, retreat rates escalated, with the Rosetta promontory losing up to 5.8 km of shoreline by the early 21st century. Similarly, the Damietta promontory experienced accelerated recession, contributing to net delta-wide land loss through wave-induced sediment redistribution without replenishment.[142][143][144] Projections based on historical satellite imagery and shallow neural network modeling forecast continued shoreline retreat, estimating cumulative erosion-induced land losses of 5.3 km² by 2030, 10.7 km² by 2040, and 18.4 km² by 2050 along exposed sectors, assuming persistent low sediment flux and prevailing hydrodynamic conditions. These models incorporate multi-decadal Landsat data, highlighting vulnerability at distributary mouths where freshwater discharge fails to counter longshore currents.[145][146] Seawater intrusion has advanced inland via breached coastal barriers and overpumping of coastal aquifers, exacerbated by reduced Nile freshwater flushing that previously maintained a seaward hydraulic gradient. This process has salinized approximately 15% of the delta's most fertile agricultural soils, impairing crop yields through elevated chloride and sodium accumulation in root zones. Empirical monitoring of irrigation canals in northern governorates documents salinity increases, with electrical conductivity routinely surpassing 2-4 dS/m thresholds for sensitive crops like rice and cotton.[147][98][148] Routine hydrochemical assessments since the 1980s reveal spatiotemporal salinity gradients in delta waterways, with northern canals exhibiting 20-50% higher total dissolved solids compared to upstream sites, correlating with proximity to eroded inlets. pH levels in affected canals have shown slight acidification trends (7.0-7.5 range), linked to ionic imbalances from marine incursions, though variability persists due to seasonal dilution. These data underscore the hydrological linkage between coastal retreat and inland salinization, independent of broader subsidence or eustatic factors.[149][150][148]Relative Impacts of Sea Level Rise

Global eustatic sea level rise has averaged approximately 3-4 mm per year in recent decades, accelerating to around 4.5 mm per year by 2023, according to satellite altimetry data.[151] [152] In the Nile Delta, however, relative sea level rise—combining eustatic changes with local land subsidence—ranges from 2.6 mm per year over the long term (1906-2020) to 3.1 mm per year in the last two decades, as recorded by tide gauges at Alexandria.[153] These rates are dominated by subsidence, driven primarily by anthropogenic factors such as excessive groundwater extraction for agriculture and urban use, which has intensified since the 1970s following the construction of the Aswan High Dam. Subsidence measurements via InSAR and GPS indicate rates of 2-7 mm per year across the delta, with peaks up to 20 mm per year in northern industrial zones linked to natural gas extraction and aquifer depletion.[92] [139] [154] Tide gauge records from Alexandria, spanning over a century, reveal a net relative rise of 1.5-2 mm per year prior to 1970, with acceleration thereafter aligning closely with subsidence onset rather than eustatic trends alone.[155] This human-induced sinking, rather than global oceanic expansion or ice melt, accounts for the majority of observed relative changes, as local vertical land motion exceeds global sea level trends by factors of 1.5-2 in many areas.[140] IPCC projections for future eustatic rise under various scenarios (e.g., 0.28-1.01 m by 2100) often underemphasize such localized subsidence in vulnerability assessments, leading some analyses to highlight that delta-specific risks are more tied to groundwater management than climate-driven sea level variability.[152] The relative impacts manifest primarily as amplified coastal erosion and heightened vulnerability in low-elevation zones, where subsidence exacerbates wave action and sediment loss along the Mediterranean frontage.[136] Without subsidence, eustatic rise alone would induce minor inundation—studies modeling isolated global components suggest less than 5% of delta land affected by a 0.5 m increase, confined to fringes—but combined effects accelerate shoreline retreat by 10-100 m per decade in subsiding sectors.[7] Critics of alarmist narratives argue that such projections overlook the delta's historical resilience through natural sediment dynamics and human engineering, with empirical data indicating that subsidence mitigation could offset much of the perceived threat independent of global trends.[140]