Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

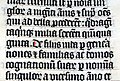

Round hand

View on Wikipedia

Round hand (also roundhand) is a type of handwriting and calligraphy originating in England in the 1660s primarily by the writing masters John Ayres and William Banson. Characterised by an open flowing hand (style) and subtle contrast of thick and thin strokes deriving from metal pointed nibs in which the flexibility of the metal allows the left and right halves of the point to spread apart under light pressure and then spring back together, the popularity of round hand grew rapidly, becoming codified as a standard, through the publication of printed writing manuals.

Origins

[edit]During the Renaissance, writing masters of the Apostolic Camera developed the italic cursiva script. When the Apostolic Camera was destroyed during the sack of Rome in 1527, many masters moved to Southern France where they began to refine the renaissance italic cursiva script into a new script, italic circumflessa.[1] By the end of the 16th century, italic circumflessa began to replace italic cursiva. Italic circumflessa was further adapted into the French style rhonde in the early 17th century.[1]

By the mid-17th century, French officials were flooded with documents written in various hands (styles) at varied levels of skills and artistry. As a result, officials began to complain that many such documents were beyond their ability to decipher.[1] France's Controller-General of Finances took proposals from French writing masters of the time, the most influential being Louis Barbedor, who had published his Les Ecritures financière et italienne-bastarde dans leur naturel, circa 1650.[1] After examining the proposals, the Controller-General of Finances decided to restrict all legal documents to three hands, namely the Coulée, the Rhonde, and a Speed Hand sometimes simply called Bastarde.[1]

In England, Edward Cocker had been publishing copybooks based upon French rhonde in the 1640s. In the 1680s, John Ayres and William Banson popularized their versions of rhonde after further refining and developing it into what had become known as English round hand style.[1]

Golden age

[edit]Later in the 17th and 18th centuries, English writing masters including George Bickham, George Shelley and Charles Snell helped to propagate Round Hand's popularity, so that by the mid-18th century the Round Hand style had spread across Europe and crossed the Atlantic to North America. The typefaces Snell Roundhand and Kuenstler Script are based on this style of handwriting. Charles Snell was particularly noted for his reaction to other variants of roundhand, developing his own Snell Roundhand, which emphasised restraint and proportionality in the script.[1]

See also

[edit]- Bastarda

- Blackletter

- Book hand

- Calligraphy

- Chancery hand

- Copperplate script

- Court hand (also known as common law hand, Anglicana, cursiva antiquior, or charter hand)

- Cursive

- Handwriting script

- Handwriting

- History of writing

- Italic script

- Palaeography

- Penmanship

- Ronde script

- Rotunda (script)

- Secretary hand

References

[edit]- Carter, Rob, Day, Ben, Meggs, Philip. Typographic Design: Form and Communication, Second Edition. Van Nostrand Reinhold, Inc: 1993 ISBN 0-442-00759-0.

- Fiedl, Frederich, Nicholas Ott and Bernard Stein. Typography: An Encyclopedic Survey of Type Design and Techniques Through History. Black Dog & Leventhal: 1998. ISBN 1-57912-023-7.

- Macmillan, Neil. An A–Z of Type Designers. Yale University Press: 2006. ISBN 0-300-11151-7.

- Nesbitt, Alexander. The History and Technique of Lettering Dover Publications, Inc.: 1998. ISBN 0-486-40281-9. The Dover edition is an abridged and corrected republication of the work originally published in 1950 by Prentice-Hall, Inc. under the title Lettering: The History and Technique of Lettering as Design.