Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

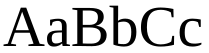

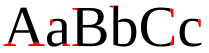

Serif

View on Wikipedia| Sans-serif font | |

|

Serif font |

|

Serif font (red serifs) |

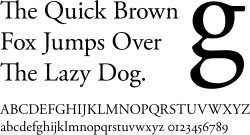

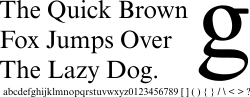

In typography, a serif (/ˈsɛrɪf/) is a small line or stroke regularly attached to the end of a larger stroke in a letter or symbol within a particular font or family of fonts. A typeface or "font family" making use of serifs is called a serif typeface (or serifed typeface), and a typeface that does not include them is sans-serif. Some typography sources refer to sans-serif typefaces as "grotesque" (in German, grotesk) or "Gothic"[1] (although this often refers to blackletter type as well). In German usage, the term Antiqua is used more broadly for serif types.

Serif typefaces can be broadly classified into one of four subgroups: Old-style, Transitional, Didone, and Slab serif, in order of first emergence.

Origins and etymology

[edit]Serifs originated from the first official Greek writings on stone and in Latin alphabet with inscriptional lettering—words carved into stone in Roman antiquity. The explanation proposed by Father Edward Catich in his 1968 book The Origin of the Serif is now broadly but not universally accepted: the Roman letter outlines were first painted onto stone, and the stone carvers followed the brush marks, which flared at stroke ends and corners, creating serifs. Another theory is that serifs were devised to neaten the ends of lines as they were chiselled into stone.[2][3][4]

The origin of the word 'serif' is obscure, but apparently is almost as recent as the type style. The book The British Standard of the Capital Letters Contained in the Roman Alphabet, Forming a Complete Code of Systematic Rules for a Mathematical Construction and Accurate Formation of the Same, with Letters of Exemplification, Elementary and Compleat: Together with an Useful and Practical Appendix by William Hollins (1813), defined 'surripses', usually pronounced "surriphs", as "projections which appear at the tops and bottoms of some letters, the O and Q excepted, at the beginning or end, and sometimes at each, of all". The standard also proposed that 'surripsis' may be a Greek word derived from σῠν- ('syn-', "together") and ῥῖψῐς ('rhîpsis', "projection").

In 1827, Greek scholar Julian Hibbert printed with his own experimental uncial Greek types, remarking that the types of Giambattista Bodoni's Callimachus were "ornamented (or rather disfigured) by additions of what [he] believe[s] type-founders call syrifs or cerefs". The printer Thomas Curson Hansard referred to them as "ceriphs" in 1825.[5] The oldest citations in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) are 1830 for 'serif' and 1841 for 'sans serif'. The OED speculates that 'serif' was a back-formation from 'sanserif'.

Webster's Third New International Dictionary traces 'serif' to the Dutch noun schreef, meaning "line, stroke of the pen", related to the verb schrappen, "to delete, strike through" ('schreef' now also means "serif" in Dutch). Yet, schreef is the past tense of schrijven (to write). The relation between schreef and schrappen is documented by Van Veen and Van der Sijs.[6] In her book Chronologisch Woordenboek,[7] Van der Sijs lists words by first known publication in the language area that is the Netherlands today:

- schrijven, 1100;

- schreef, 1350;

- schrappen, 1406 (i.e. schreef is from schrijven (to write), not from schrappen (to scratch, eliminate by strike-through)).

The OED's earliest citation for "grotesque" in this sense is 1875, giving 'stone-letter' as a synonym. It would seem to mean "out of the ordinary" in this usage, as in art 'grotesque' usually means "elaborately decorated". Other synonyms include "Doric" and "Gothic", commonly used for Japanese Gothic typefaces.[8]

Classification

[edit]Old-style

[edit]

Old-style typefaces date back to 1465, shortly after Johannes Gutenberg's adoption of the movable type printing press. Early printers in Italy created types that broke with Gutenberg's blackletter printing, creating upright ("roman") and then oblique ("italic") styles that were inspired by Renaissance calligraphy.[9][10] Old-style serif fonts have remained popular for setting body text because of their organic appearance and excellent readability on rough book paper. The increasing interest in early printing during the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a return to the designs of Renaissance printers and type-founders, many of whose names and designs are still used today.[11][12][13]

Old-style type is characterized by a lack of large differences between thick and thin lines (low line contrast) and generally, but less often, by a diagonal stress (the thinnest parts of letters are at an angle rather than at the top and bottom). An old-style font normally has a left-inclining curve axis with weight stress at about 8 and 2 o'clock; serifs are almost always bracketed (they have curves connecting the serif to the stroke); head serifs are often angled.[14]

Old-style faces evolved over time, showing increasing abstraction from what would now be considered handwriting and blackletter characteristics, and often increased delicacy or contrast as printing technique improved.[10][15][16] Old-style faces have often sub-divided into 'Venetian' (or 'humanist') and 'Garalde' (or 'Aldine'), a division made on the Vox-ATypI classification system.[17] Nonetheless, some have argued that the difference is excessively abstract, hard to spot except to specialists and implies a clearer separation between styles than originally appeared.[18][b] Modern typefaces such as Arno and Trinité may fuse both styles.[21]

Early "humanist" roman types were introduced in Italy. Modelled on the script of the period, they tend to feature an "e" in which the cross stroke is angled, not horizontal; an "M" with two-way serifs; and often a relatively dark colour on the page.[9][10] In modern times, that of Nicolas Jenson has been the most admired, with many revivals.[22][9] Garaldes, which tend to feature a level cross-stroke on the "e", descend from an influential 1495 font cut by engraver Francesco Griffo for printer Aldus Manutius, which became the inspiration for many typefaces cut in France from the 1530s onwards.[23][24] Often lighter on the page and made in larger sizes than had been used for roman type before, French Garalde faces rapidly spread throughout Europe from the 1530s to become an international standard.[19][23][25]

Also during this period, italic type evolved from a quite separate genre of type, intended for informal uses such as poetry, into taking a secondary role for emphasis. Italics moved from being conceived as separate designs and proportions to being able to be fitted into the same line as roman type with a design complementary to it.[26][27][28][c]

Examples of contemporary Garalde old-style typefaces are Bembo, Garamond, Galliard, Granjon, Goudy Old Style, Minion, Palatino, Renard, Sabon, and Scala. Contemporary typefaces with Venetian old style characteristics include Cloister, Adobe Jenson, the Golden Type, Hightower Text, Centaur, Goudy's Italian Old Style and Berkeley Old Style and ITC Legacy. Several of these blend in Garalde influences to fit modern expectations, especially placing single-sided serifs on the "M"; Cloister is an exception.[30]

Dutch taste

[edit]A new genre of serif type developed around the 17th century in the Netherlands and Germany that came to be called the "Dutch taste" (goût Hollandois in French).[31] It was a tendency towards denser, more solid typefaces, often with a high x-height (tall lower-case letters) and a sharp contrast between thick and thin strokes, perhaps influenced by blackletter faces.[32][33][31][34][35]

Artists in the "Dutch taste" style include Hendrik van den Keere, Nicolaas Briot, Christoffel van Dijck, Miklós Tótfalusi Kis and the Janson and Ehrhardt types based on his work and Caslon, especially the larger sizes.[34]

Transitional

[edit]

Transitional, or baroque, serif typefaces first became common around the mid-18th century until the start of the 19th.[36] They are in between "old style" and "modern" fonts, thus the name "transitional". Differences between thick and thin lines are more pronounced than they are in old style, but less dramatic than they are in the Didone fonts that followed. Stress is more likely to be vertical, and often the "R" has a curled tail. The ends of many strokes are marked not by blunt or angled serifs but by ball terminals. Transitional faces often have an italic 'h' that opens outwards at bottom right.[37] Because the genre bridges styles, it is difficult to define where the genre starts and ends. Many of the most popular transitional designs are later creations in the same style.

Fonts from the original period of transitional typefaces include early on the "romain du roi" in France, then the work of Pierre Simon Fournier in France, Fleischman and Rosart in the Low Countries,[38] Pradell in Spain and John Baskerville and Bulmer in England.[39][40] Among more recent designs, Times New Roman (1932), Noto Serif, Perpetua, Plantin, Mrs. Eaves, Freight Text, and the earlier "modernised old styles" have been described as transitional in design.[d]

Later 18th-century transitional typefaces in Britain begin to show influences of Didone typefaces from Europe, described below, and the two genres blur, especially in type intended for body text; Bell is an example of this.[42][43][e]

Didone

[edit]

Didone, or modern, serif typefaces, which first emerged in the late 18th century, are characterized by extreme contrast between thick and thin lines.[f] These typefaces have a vertical stress and thin serifs with a constant width, with minimal bracketing (constant width). Serifs tend to be very thin, and vertical lines very heavy. Didone fonts are often considered to be less readable than transitional or old-style serif typefaces. Period examples include Bodoni, Didot, and Walbaum. Computer Modern is a popular contemporary example. The very popular Century is a softened version of the same basic design, with reduced contrast.[46] Didone typefaces achieved dominance of printing in the early 19th-century printing before declining in popularity in the second half of the century and especially in the 20th as new designs and revivals of old-style faces emerged.[47][48][49]

In print, Didone fonts are often used on high-gloss magazine paper for magazines such as Harper's Bazaar, where the paper retains the detail of their high contrast well, and for whose image a crisp, "European" design of type may be considered appropriate.[50][51] They are used more often for general-purpose body text, such as book printing, in Europe.[51][52] They remain popular in the printing of Greek, as the Didot family were among the first to establish a printing press in newly independent Greece.[53][54] The period of Didone types' greatest popularity coincided with the rapid spread of printed posters and commercial ephemera and the arrival of bold type.[55][56] As a result, many Didone typefaces are among the earliest designed for "display" use, with an ultra-bold "fat face" style becoming a common sub-genre.[57][58][59]

Slab serif

[edit]

Slab serif typefaces date to about 1817.[g][60] Originally intended as attention-grabbing designs for posters, they have very thick serifs, which tend to be as thick as the vertical lines themselves. Slab serif fonts vary considerably: some, such as Rockwell, have a geometric design with minimal variation in stroke width—they are sometimes described as sans-serif fonts with added serifs. Others, such as those of the "Clarendon" model, have a structure more like most other serif fonts, though with larger and more obvious serifs.[61][62] These designs may have bracketed serifs that increase width along their length.

Because of the clear, bold nature of the large serifs, slab serif designs are often used for posters and in small print. Many monospace fonts, on which all characters occupy the same amount of horizontal space as in a typewriter, are slab-serif designs. While not always purely slab-serif designs, many fonts intended for newspaper use have large slab-like serifs for clearer reading on poor-quality paper. Many early slab-serif types, being intended for posters, only come in bold styles with the key differentiation being width, and often have no lower-case letters at all.

Examples of slab-serif typefaces include Clarendon, Rockwell, Archer, Courier, Excelsior, TheSerif, and Zilla Slab. FF Meta Serif and Guardian Egyptian are examples of newspaper and small print-oriented typefaces with some slab-serif characteristics, often most visible in the bold weights. In the late 20th century, the term "humanist slab-serif" has been applied to typefaces such as Chaparral, Caecilia and Tisa, with strong serifs but an outline structure with some influence of old-style serif typefaces.[63][64][65]

Other styles

[edit]During the 19th century, genres of serif type besides conventional body text faces proliferated.[66] These included "Tuscan" faces, with ornamental, decorative ends to the strokes rather than serifs, and "Latin" or "wedge-serif" faces, with pointed serifs, which were particularly popular in France and other parts of Europe including for signage applications such as business cards or shop fronts.[67]

Well-known typefaces in the "Latin" style include Wide Latin, Copperplate Gothic, Johnston Delf Smith and the more restrained Méridien.

Readability and legibility

[edit]Serifed typefaces are widely used for body text because they are considered easier to read than sans-serif typefaces in print.[68] Colin Wheildon, who conducted scientific studies from 1982 to 1990, found that sans-serif typefaces created various difficulties for readers that impaired their comprehension.[69] According to Kathleen Tinkel, studies suggest that "most sans serif typefaces may be slightly less legible than most serif faces, but ... the difference can be offset by careful setting".[70]

Sans-serif fonts are considered to be more legible on computer screens. According to Alex Poole,[71] "we should accept that most reasonably designed typefaces in mainstream use will be equally legible". A study suggested that serif typefaces are more legible on a screen but are not generally preferred to sans-serif typefaces.[72] Another study indicated that comprehension times for individual words are slightly faster when written in a sans-serif typeface versus a serif typeface.[73]

When size of an individual glyph is 9–20 pixels, proportional serifs and some lines of most glyphs of common vector typefaces are smaller than individual pixels. Hinting, spatial anti-aliasing, and subpixel rendering allow systems to render distinguishable serifs even in this case, but their proportions and appearances are off, and their thicknesses are close to many lines of the main glyph, strongly altering appearance of the glyph. Consequently, it is sometimes advised to use sans-serif typefaces for content meant to be displayed on screens, as they scale better for low resolutions. Indeed, most web pages employ sans-serif type.[74] The recent[when?] introduction of desktop displays with 300+ dpi resolution might eventually make this recommendation obsolete.

As serifs originated in inscription, they are generally not used in handwriting. A common exception is the printed capital I, where the addition of serifs distinguishes the character from lowercase L (l). The printed capital J and the numeral 1 are also often handwritten with serifs.

Gallery

[edit]Below are some images of serif letterforms across history:

-

The roman type of Nicolas Jenson

-

De Aetna, printed by Aldus Manutius

-

Title page printed by Robert Estienne

-

Great Primer type (c. 18 pt) by Claude Garamond

-

Gros Canon type by Garamond

-

1611 book, with arabesque ornament border

-

Large roman by Hendrik van den Keere, introducing the "Dutch taste" style

-

Type by Christoffel van Dijck

-

The Romain du roi, the first "transitional" typeface

-

Condensed, high x-height types in the "Dutch taste" style, c. 1720

-

Title page by John Baskerville, 1757

-

Alphabet by Pierre-Simon Fournier in his Manuel typographique, 1760s

-

Transitional type by Joan Michaël Fleischman of Amsterdam, 1768

-

Modern-face types by the Amoretti Brothers, 1797

-

Didone type in a book printed by the company of Firmin Didot, 1804

-

Bodoni's posthumous Manuale Tipografico, 1818

-

Inline modern face

-

Display type with pattern inside

-

"Fat face" ultra-bold Didone type

-

The original Clarendon typeface

-

Display-size slab-serifs

-

Miller and Richard's Modernised Old Style, a reimagination of pre-Didone typefaces

-

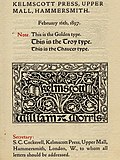

William Morris's Golden Type in the style of Jenson and other typefaces of his Kelmscott Press

-

ATF's "Garamond" type, an example of historicist printing

-

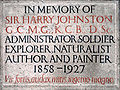

Memorial plaque by Eric Gill, c. 1920s

-

Sample of the Linotype Legibility Group typefaces, the most popular newspaper typefaces during the twentieth century.[75]

-

Humanist slab-serif PNM Caecilia on an Amazon Kindle

Analogues in other writing systems

[edit]East Asia

[edit]

In the Chinese and Japanese writing systems, there are common type styles based on the regular script for Chinese characters akin to serif and sans serif fonts in the West. In Mainland China, the most popular category of serifed-like typefaces for body text is called Song (宋体, Songti); in Japan, the most popular serif style is called Minchō (明朝); and in Taiwan and Hong Kong, it is called Ming (明體, Mingti). The names of these lettering styles come from the Song and Ming dynasties, when block printing flourished in China. Because the wood grain on printing blocks ran horizontally, it was fairly easy to carve horizontal lines with the grain. However, carving vertical or slanted patterns was difficult because those patterns intersect with the grain and break easily. This resulted in a typeface that has thin horizontal strokes and thick vertical strokes.[citation needed] In accordance with Chinese calligraphy (kaiti style in particular), where each horizontal stroke is ended with a dipping motion of the brush, the ending of horizontal strokes are also thickened.[citation needed] These design forces resulted in the current Song typeface characterized by thick vertical strokes contrasted with thin horizontal strokes, triangular ornaments at the end of single horizontal strokes, and overall geometrical regularity.

In Japanese typography, the equivalent of serifs on kanji and kana characters are called uroko—"fish scales". In Chinese, the serifs are called either yǒujiǎotǐ (有脚体, lit. "forms with legs")[citation needed] or yǒuchènxiàntǐ (有衬线体, lit. "forms with ornamental lines").

The other common East Asian style of type is called black (黑体/體, Hēitǐ) in Chinese and Gothic (ゴシック体, Goshikku-tai) in Japanese. This group is characterized by lines of even thickness for each stroke, the equivalent of "sans serif". This style, first introduced on newspaper headlines, is commonly used on headings, websites, signs and billboards. A Japanese-language font designed in imitation of western serifs also exists.[76]

Thai

[edit]Farang Ses, designed in 1913, was the first Thai typeface to employ thick and thin strokes reflecting old-style serif Latin typefaces, and became extremely popular, with its derivatives widely used into the digital age. (Examples: Angsana UPC, Kinnari)[77]

Compared to blackletter

[edit]In Germany and other Central European countries, blackletter remained the norm in body text for longer than in Western Europe; see the Antiqua–Fraktur dispute, often dividing along ideological or political lines. After the mid-20th century, Fraktur fell out of favor and Antiqua-based typefaces became the official standard in Germany. (In German, the term "Antiqua" refers to serif typefaces.[78])

See also

[edit]- Homoglyph

- Ming (typeface), a similar style in Asian typefaces

- The analogs of serifs, known in Japanese as 鱗 uroko, literally "fish scales"

- San Serriffe, an elaborate typographic joke

Lists of serif typefaces

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Note that this image includes 'Th' ligatures, common in Adobe typefaces but not found in the 16th century.

- ^ Specifically, Manutius's type, the first type now classified as "Garalde", was not so different from other typefaces around at the time.[9] However, the waves of "Garalde" faces coming out of France from the 1530s onwards did tend to cleanly displace earlier typefaces, and became an international standard.[19][20]

- ^ Early italics were intended to exist on their own on the page, and so often had very long ascenders and descenders, especially the "chancery italics" of printers such as Arrighi.[29] Jan van Krimpen's Cancelleresca Bastarda typeface, intended to complement his serif family Romulus, was nonetheless cast on a larger body to allow it to have an appropriately expansive feel.

- ^ Monotype executive Stanley Morison, who commissioned Times New Roman, noted that he hoped that it "has the merit of not looking as if it had been designed by somebody in particular".[41]

- ^ It should be realised that "Transitional" is a somewhat nebulous classification, almost always including Baskerville and other typefaces around this period but also sometimes including 19th and 20th-century reimaginations of old-style faces, such as Bookman and Plantin, and sometimes some of the later "old-style" faces such as the work of Caslon and his imitators. In addition, of course Baskerville and others of this period would not have seen their work as "transitional" but as an end in itself. Eliason (2015) provides a leading modern critique and assessment of the classification, but even in 1930 A.F. Johnson called the term "vague and unsatisfactory."[42][44]

- ^ Additional subgenres of Didone type include "fat faces" (ultra-bold designs for posters) and "Scotch Modern" designs (used in the English-speaking world for book and newspaper printing).[45]

- ^ Early slab-serif types were given a variety of names for branding purposes, such as 'Egyptian', 'Italian', 'Ionic', 'Doric', 'French-Clarendon' and 'Antique', which generally have little or no connection to their actual history. Nonetheless, the names have persisted in use.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Phinney, Thomas. "Sans Serif: Gothic and Grotesque". TA. Showker Graphic Arts & Design. Showker. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ Samara, Timothy (2004). Typography workbook: a real-world guide to using type in graphic design. Rockport Publishers. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-59253-081-6. Archived from the original on 2024-02-09. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ Goldberg, Rob (2000). Digital Typography: Practical Advice for Getting the Type You Want When You Want It. Windsor Professional Information. p. 264. ISBN 978-1-893190-05-4.

- ^ The Linotype Bulletin. January–February 1921. p. 265. Archived from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2011.

- ^ Hansard, Thomas Curson (1825). Typographia, an Historical Sketch of the Origin and Progress of the Art of Printing. p. 370. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Etymologisch Woordenboek (Van Dale, 1997).

- ^ (Veen, 2001).

- ^ Berry, John. "A Neo-Grotesque Heritage". Adobe Systems. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d Boardley, John (18 April 2016). "The first roman fonts". ilovetypography. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Olocco, Riccardo. "The Venetian origins of roman type". Medium. C-A-S-T. Archived from the original on 13 November 2023. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ Mosley, James (2006). "Garamond, Griffo and Others: The Price of Celebrity". Bibiologia. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ Coles, Stephen. "Top Ten Typefaces Used by Book Design Winners". FontFeed (archived). Archived from the original on 2012-02-28. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Johnson, A.F. (1931). "Old-Face Types in the Victorian Age" (PDF). Monotype Recorder. 30 (242): 5–15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ "Old Style Serif". Archived from the original on 2009-02-21. Retrieved 2009-06-25.

- ^ Boardley, John (7 February 2014). "Unusual fifteenth-century fonts: part 1". i love typography. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ Boardley, John (July 2015). "Unusual fifteenth-century fonts: part 2". i love typography. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ "Type anatomy: Family Classifications of Type". SFCC Graphic Design department. Spokane Falls Community College. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Dixon, Catherine (2002), "Twentieth Century Graphic Communication: Technology, Society and Culture", Typeface classification, Friends of St Bride, archived from the original on 2014-10-26, retrieved 2015-08-14

- ^ a b Amert, Kay (April 2008). "Stanley Morison's Aldine Hypothesis Revisited". Design Issues. 24 (2): 53–71. doi:10.1162/desi.2008.24.2.53. S2CID 57566512.

- ^ The Aldine Press: catalogue of the Ahmanson-Murphy collection of books by or relating to the press in the Library of the University of California, Los Angeles : incorporating works recorded elsewhere. Berkeley [u.a.]: Univ. of California Press. 2001. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-0-520-22993-8.

[On the Aldine Press in Venice changing over to types from France]: the press followed precedent; popular in France, [these] types rapidly spread over western Europe.

- ^ Twardoch, Slimbach, Sousa, Slye (2007). Arno Pro (PDF). San Jose: Adobe Systems. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Olocco, Riccardo. "Nicolas Jenson and the success of his roman type". Medium. C-A-S-T. Archived from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ a b Vervliet, Hendrik D.L. (2008). The palaeotypography of the French Renaissance. Selected papers on sixteenth-century typefaces. 2 vols. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. pp. 90–91, etc. ISBN 978-90-04-16982-1.

[On Robert Estienne's typefaces of the 1530s]: Its outstanding design became standard for Roman type in the two centuries to follow...From the 1540s onwards French Romans and Italics had begun to infiltrate, probably by way of Lyons, the typography of the neighbouring countries. In Italy, major printers replaced the older, noble but worn Italian characters and their imitations from Basle.

- ^ Carter, Harry (1969). A View of Early Typography up to about 1600 (Second edition (2002) ed.). London: Hyphen Press. pp. 72–4. ISBN 0-907259-21-9.

De Aetna was decisive in shaping the printers' alphabet. The small letters are very well made to conform with the genuinely antique capitals by emphasis on long straight strokes and fine serifs and to harmonise in curvature with them. The strokes are thinner than those of Jenson and his school...the letters look narrower than Jenson's, but are in fact a little wider because the short ones are bigger, and the effect of narrowness makes the face suitable for octavo pages...this Roman of Aldus is distinguishable from other faces of the time by the level cross-stroke in 'e' and the absence of top serifs from the insides of the vertical strokes of 'M', following the model of Feliciano. We have come to regard his small 'e' as an improvement on previous practice.

- ^ Bergsland, David (29 August 2012). "Aldine: the intellectuals begin their assault on font design". The Skilled Workman. Archived from the original on 17 January 2022. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ Boardley, John (25 November 2014). "Brief notes on the first italic". i love typography. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ^ Vervliet, Hendrik D. L. (2008). The Palaeotypography of the French Renaissance: Selected Papers on Sixteenth-century Typefaces. BRILL. pp. 287–289. ISBN 978-90-04-16982-1. Archived from the original on 2023-11-01. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- ^ Lane, John (1983). "The Types of Nicholas Kis". Journal of the Printing Historical Society: 47–75.

Kis's Amsterdam specimen of c. 1688 is an important example of the increasing tendency to regard a range of roman and italic types as a coherent family, and this may well have been a conscious innovation. But italics were romanised to a greater degree in many earlier handwritten examples and occasional earlier types, and Jean Jannon displayed a full range of matching roman and italic of his own cutting in his 1621 specimen...[In appendix] [György] Haiman notes that this trend is foreshadowed in the specimens of Guyot in the mid-sixteenth century and Berner in 1592.

- ^ Vervliet, Hendrik D. L. (2008). The Palaeotypography of the French Renaissance: Selected Papers on Sixteenth-century Typefaces. BRILL. pp. 287–319. ISBN 978-90-04-16982-1. Archived from the original on 2023-11-01. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- ^ Shen, Juliet. "Searching for Morris Fuller Benton". Type Culture. Archived from the original on 11 April 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ^ a b Johnson, A. F. (1939). "The 'Goût Hollandois'". The Library. s4-XX (2): 180–196. doi:10.1093/library/s4-XX.2.180.

- ^ Updike, Daniel Berkeley (1922). "Chapter 15: Types of the Netherlands, 1500-1800". Printing Types: Their History, Forms and Uses: Volume 2. Harvard University Press. pp. 6–7. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- ^ "Type History 1". Typofonderie Gazette. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ a b Mosley, James. "Type and its Uses, 1455-1830" (PDF). Institute of English Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

Although types on the 'Aldine' model were widely used in the 17th and 18th centuries, a new variant that was often slightly more condensed in its proportions, and darker and larger on its body, became sufficiently widespread, at least in Northern Europe, to be worth defining as a distinct style and examining separately. Adopting a term used by Fournier le jeune, the style is sometimes called the 'Dutch taste', and sometimes, especially in Germany, 'baroque'. Some names associated with the style are those of Van den Keere, Granjon, Briot, Van Dijck, Kis (maker of the so-called 'Janson' types), and Caslon.

- ^ de Jong, Feike; Lane, John A. "The Briot project. Part I". PampaType. TYPO, republished by PampaType. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ Paul Shaw (18 April 2017). Revival Type: Digital Typefaces Inspired by the Past. Yale University Press. pp. 85–98. ISBN 978-0-300-21929-6. Archived from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ Morison, Stanley (1937). "Type Designs of the Past and Present, Part 3". PM: 17–81. Archived from the original on 2017-09-04. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Jan Middendorp (2004). Dutch Type. 010 Publishers. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-90-6450-460-0.

- ^ Corbeto, A. (25 September 2009). "Eighteenth Century Spanish Type Design". The Library. 10 (3): 272–297. doi:10.1093/library/10.3.272. S2CID 161371751.

- ^ Unger, Gerard (1 January 2001). "The types of François-Ambroise Didot and Pierre-Louis Vafflard. A further investigation into the origins of the Didones". Quaerendo. 31 (3): 165–191. doi:10.1163/157006901X00047.

- ^ Alas, Joel. "The history of the Times New Roman typeface". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ a b Johnson, Alfred F. (1930). "The Evolution of the Modern-Face Roman". The Library. s4-XI (3): 353–377. doi:10.1093/library/s4-XI.3.353.

- ^ Johnston, Alastair (2014). Transitional Faces: The Lives & Work of Richard Austin, type-cutter, and Richard Turner Austin, wood-engraver. Berkeley: Poltroon Press. ISBN 978-0918395320. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ Eliason, Craig (October 2015). ""Transitional" Typefaces: The History of a Typefounding Classification". Design Issues. 31 (4): 30–43. doi:10.1162/DESI_a_00349. S2CID 57569313.

- ^ Shinn, Nick. "Modern Suite" (PDF). Shinntype. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ Shaw, Paul (10 February 2011). "Overlooked Typefaces". Print magazine. Archived from the original on 22 June 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Ovink, G.W. (1971). "Nineteenth-century reactions against the didone type model - I". Quaerendo. 1 (2): 18–31. doi:10.1163/157006971x00301.

- ^ Ovink, G.W. (1971). "Nineteenth-century reactions against the didone type model - II". Quaerendo. 1 (4): 282–301. doi:10.1163/157006971x00239.

- ^ Ovink, G.W. (1 January 1972). "Nineteenth-century reactions against the didone type model-III". Quaerendo. 2 (2): 122–128. doi:10.1163/157006972X00229.

- ^ Frazier, J. L. (1925). Type Lore. Chicago. p. 14. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "HFJ Didot introduction". Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Archived from the original on 14 August 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ "HFJ Didot". Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Leonidas, Gerry. "A primer on Greek type design". Gerry Leonidas/University of Reading. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ^ "GFS Didot". Greek Font Society. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Eskilson, Stephen J. (2007). Graphic design : a new history. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 25. ISBN 9780300120110.

- ^ Pané-Farré, Pierre. "Affichen-Schriften". Forgotten-Shapes. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Alfred F. (1970). "Fat Faces: Their History, Forms and Use". Selected Essays on Books and Printing. pp. 409–415.

- ^ Phinney, Thomas. "Fat faces". Graphic Design and Publishing Centre. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Kennard, Jennifer (3 January 2014). "The Story of Our Friend, the Fat Face". Fonts in Use. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- ^ Miklavčič, Mitja (2006). Three chapters in the development of clarendon/ionic typefaces (PDF) (MA Thesis). University of Reading. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 25, 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ "Sentinel: historical background". Hoefler & Frere-Jones. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ Challand, Skylar. "Know your type: Clarendon". IDSGN. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Phinney, Thomas. "Most Overlooked: Chaparral". Typekit Blog. Adobe Systems. Archived from the original on 16 February 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ Lupton, Ellen (12 August 2014). Type on Screen: A Critical Guide for Designers, Writers, Developers, and Students. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-61689-346-0. Archived from the original on 9 February 2024. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ Bringhurst, Robert (2002). The Elements of Typographic Style (2nd ed.). Hartley & Marks. pp. 218, 330. ISBN 9780881791327.

- ^ Gray, Nicolete (1976). Nineteenth-century Ornamented Typefaces.

- ^ Frutiger, Adrian (8 May 2014). Typefaces – the complete works. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 26–35. ISBN 9783038212607.

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Manual for Writers and Editors, (Springfield, 1998) p. 329.

- ^ Wheildon, Colin (1995). Type and Layout: How Typography and Design Can Get your Message Across – Or Get in the Way. Berkeley: Strathmoor Press. pp. 57, 59–60. ISBN 0-9624891-5-8.

- ^ Kathleen Tinkel, "Taking it in: What makes type easy to read", adobe.com Archived 2012-10-19 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 28 December 2010. p. 3.

- ^ Literature Review Which Are More Legible: Serif or Sans Serif Typefaces? alexpoole.info Archived 2010-03-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Effects of Font Type on the Legibility The Effects of Font Type and Size on the Legibility and Reading Time of Online Text by Older Adults. psychology.wichita.edu Archived 2009-10-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Moret-Tatay, C., & Perea, M. (2011). Do serifs provide an advantage in the recognition of written words? Journal of Cognitive Psychology 23, 5, 619-24.. valencia.edu Archived 2011-05-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ The Principles of Beautiful Web Design, (2007) p. 113.

- ^ Hutt, Allen (1973). The Changing Newspaper: typographic trends in Britain and America 1622-1972 (1. publ. ed.). London: Fraser. pp. 100–2 etc. ISBN 9780900406225.

the majority of the world's newspapers are typeset in one or another of the traditional Linotype 'Legibility Group', and most of the rest in their derivatives.

- ^ "和文フォント大図鑑 [ダイナコムウェア/その他]".

- ^ Pracha Suveeranont. "ฝรั่งเศส". ๑๐ ตัวพิมพ์ กับ ๑๐ ยุคสังคมไทย (10 Faces of Thai Type and Thai Nation) (in Thai). Thaifaces. Retrieved 22 May 2020. Originally exhibited 18–31 October 2002 at the Jamjuree Art Gallery, Chulalongkorn University, and published in Sarakadee. 17 (211). September 2002.

- ^ "Renner Antiqua – Reviving a serif typeface from the designer of Futura". Linotype.

Antiqua is a term used in German to denote serif typefaces, many of them oldstyles (Garamond-Antiqua, Palatino-Antiqua, etc.). The word is used in very much the same way as "roman" [is used] in English-speaking typography to differentiate between upright and italic typefaces in a family.

Bibliography

[edit]- Robert Bringhurst, The Elements of Typographic Style, version 4.0 (Vancouver, BC, Canada: Hartley & Marks Publishers, 2012), ISBN 0-88179-211-X.

- Harry Carter, A View of Early Typography: Up to about 1600 (London: Hyphen Press, 2002).

- Father Edward Catich, The Origin of the Serif: Brush Writing and Roman Letters, 2nd ed., edited by Mary W. Gilroy (Davenport, Iowa: Catich Gallery, St. Ambrose University, 1991), ISBN 9780962974021.

- Nicolete Gray, Nineteenth Century Ornamented Typefaces, 2nd ed. (Faber, 1976), ISBN 9780571102174.

- Alfred F. Johnson, Type Designs: Their History and Development (Grafton, 1959).

- Stan Knight, Historical Types: From Gutenberg to Ashendene (Oak Knoll Press, 2012), ISBN 9781584562986.

- Ellen Lupton, Thinking with Type: A Critical Guide for Designers, Writers, Editors, & Students, 2nd ed. (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2010), ISBN 9781568989693, <www.thinkingwithtype.com>.

- Indra Kupferschmid, "Some Type Genres Explained," Type, kupferschrift.de (2016-01-15).

- Stanley Morison, A Tally of Types, edited by Brooke Crutchley et al., 2nd ed. (London: Cambridge University Press, 1973), ISBN 978-0-521-09786-4. (on revivals of historical typefaces created by the British company Monotype)

- ———, “Type Designs of the Past and Present,” was serialized in 4 parts in 1937 in PM Magazine (the last 2 are available online):

- “Part 1,” PM Magazine, 4, 1 (1937-09);

- “Part 2,” PM Magazine, 4, 2 (1937-12);

- “Part 3 Archived 2017-09-04 at the Wayback Machine,” PM Magazine, 4, 3 (1937-11): 17–32;

- “Part 4 Archived 2021-07-24 at the Wayback Machine,” PM Magazine, 4, 4 (1937-12): 61–81.

- Sébastien Morlighem, The 'modern face' in France and Great Britain, 1781-1825: typography as an ideal of progress (thesis, University of Reading, 2014), download link

- Sébastien Morlighem, Robert Thorne and the Introduction of the 'modern' fat face, 2020, Poem, and presentation

- James Mosley, Ornamented types: twenty-three alphabets from the foundry of Louis John Poucheé, I.M. Imprimit, 1993

- Paul Shaw, Revival Type: Digital Typefaces Inspired by the Past (Brighton: Quid Publishing, 2017), ISBN 978-0-300-21929-6.

- Walter Tracy, Letters of Credit: A View of Type Design, 2nd ed. (David R. Godine, 2003), ISBN 9781567922400.

- Daniel Berkeley Updike, Printing Types, their History, Forms, and Use: A Study in Survivals, 2 vols. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1922), volume 1 and volume 2—now outdated and known for a strong, not always accurate dislike of Dutch and modern-face printing, but extremely comprehensive in scope.

- H. D. L. Vervliet, The Palaeotypography of the French Renaissance: Selected Papers on Sixteenth-Century Typefaces, 2 vols., Library of the Written Word series, No. 6, The Handpress World subseries, No. 4 (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2008-11-27), ISBN 978-90-04-16982-1.

- ———, Sixteenth Century Printing Types of the Low Countries, Annotated catalogue (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV, 1968-01-01), ISBN 978-90-6194-859-9.

- ———, French Renaissance Printing Types: A Conspectus (Oak Knoll Press, 2010).

- ———, Liber librorum: 5000 ans d'art du livre (Arcade, 1972).

- Translation: Fernand Baudin, The Book Through Five Thousand Years: A Survey, edited by Hendrik D. L. Vervliet (London: Phaidon, 1972).

- James Mosley's reading lists: "Type and its Uses, 1455–1830", 1830-2000

Serif

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Core Definition and Visual Features

A serif is a small line or stroke regularly attached to the end of a larger stroke in a letter or symbol within a typeface family.[1] Serif typefaces incorporate these projections or flourishes at the extremities of character strokes, distinguishing them from sans-serif typefaces that lack such features.[8] The term applies specifically to the decorative elements themselves, though "serif" is often used interchangeably to describe typefaces featuring them.[4] Visually, serifs terminate the main strokes of letters, providing a sense of completion and guiding the eye along lines of text through subtle horizontal emphasis.[1] These elements vary in form, appearing as tapered wedges, slabs, or hairline extensions, which contribute to the typeface's overall rhythm and perceived stability.[9] In printed media, serifs can enhance legibility by creating a visual base for characters, reducing the starkness of vertical and horizontal lines.[8] The presence of serifs imparts a traditional or formal aesthetic, often evoking historical printing traditions.[10]Functions of Serifs in Letterforms

Serifs function in letterforms by providing distinct terminations to the ends of strokes, which aids in the visual identification of individual characters. This structural feature offers perceptual cues that delineate stroke boundaries, potentially enhancing the recognition of letter shapes amid dense text.[5] In traditional typography, serifs are credited with guiding the eye along horizontal lines, facilitating smoother reading flow and reducing visual fatigue during prolonged exposure to printed matter.[11][1] Empirical investigations into readability, however, reveal no consistent superiority of serif over sans-serif typefaces. Controlled studies indicate that differences in reading speed and comprehension between the two are minimal, with factors like font size, contrast, and medium exerting greater influence. For instance, research on print materials found serif fonts with high stroke contrast performing comparably to low-contrast sans serifs, while screen-based tasks often favor sans serifs due to pixel rendering.[12][6][13] Traditional claims of serif-enhanced legibility in body text persist in book design, yet meta-analyses underscore the variability tied to individual reader preferences and contextual demands rather than inherent typographic traits.[14][15] From a design perspective rooted in historical practice, serifs contribute to uniform text color by distributing ink more evenly on irregular paper surfaces, a practical adaptation from early printing technologies.[16] They also emulate the flared ends observed in ancient Roman stone inscriptions, where serifs arose from tool marks or deliberate expansions to prevent chipping and ensure alignment.[17] This origin informs their role in creating rhythmic continuity across letterforms, though modern digital reproduction diminishes such mechanical necessities.[18]Historical Origins

Roman Inscriptions and Early Development

Serifs first appeared in ancient Roman monumental inscriptions, particularly in the capitalis monumentalis script used for carving durable messages into stone monuments and public architecture. This style, exemplified by the inscription on Trajan's Column dedicated in AD 113, featured uppercase letters with thick and thin strokes, angled stressing, and incised serifs—short, horizontal or angled terminals at stroke ends that provided visual weight distribution and prevented edge fracturing during chisel work.[19][20] The serifs likely emerged from practical stoneworking methods: masons outlined letters with a flat brush on the stone surface before incising, leaving thin paint trails that influenced the final carved form, or initiated cuts at shallow angles to guide the chisel and minimize chipping along brittle horizontal strokes.[3][2] While earlier Greek inscriptions from the 3rd century BC occasionally showed similar terminals, Roman adoption standardized serifs in Latin epigraphy by the 2nd century BC, evolving from rudimentary square capitals (capitalis quadrata) into the refined, proportioned forms of capitalis monumentalis for imperial propaganda and legal texts.[16] These inscriptions prioritized legibility at distance and permanence, with serifs enhancing optical clarity by bracketing strokes and countering the illusion of foreshortening in vertical elements.[21] Serifed forms persisted through medieval manuscripts, where insular and uncial scripts adapted inscriptional capitals, though with softer, less incised terminals due to quill-based writing.[22] The transition to early printed typefaces occurred during the 15th-century Italian Renaissance, as humanist scholars revived classical texts and commissioned types mimicking inscriptional proportions to evoke antiquity's authority. Printers Arnold Sweynheym and Conrad Pannartz introduced proto-roman faces in their 1465 Subiaco editions, but Nicolas Jenson's 1470 Venetian roman type refined serifs with bracketed, calligraphic modulation drawn directly from capitalis monumentalis, marking the foundation of modern serif typography in movable type.[2][22] This development bridged epigraphic tradition to mass reproduction, prioritizing readability and classical fidelity over Gothic blackletter's density.[21]Etymology and Linguistic Roots

The English term "serif," denoting the short finishing stroke at the end of a letter's main stroke in typography, first appears in print around 1785, with more consistent letter-founders' usage by 1841.[23][24] Earlier variants such as "ceref," "ceriph," or "seriph" are attested from 1827, reflecting its emergence in the specialized lexicon of type founding during the industrial expansion of printing in the early 19th century.[24] The word's etymology remains uncertain but is most commonly traced to Dutch "schreef" or "schrift," terms for a line, stroke, or script, which entered English through the influence of Flemish and Dutch type designers and founders active in 17th- and 18th-century Europe.[3][25] These Dutch forms derive from the verb "schrijven" (to write or draw a line), a Germanic cognate ultimately borrowing from Latin scribere ("to scratch" or "to write"), evoking the incising action in early letterforms.[26] Alternative theories propose a medieval Latin root like cerificus ("waxen" or "made like wax writing"), linking to stylus impressions on wax tablets that left subtle terminal flourishes, though this lacks direct textual evidence and is considered speculative.[26] Cognates in other languages highlight parallel conceptual roots: French empattement (from Latin im- "in" + pattus "paw," implying a foot-like base) and Italian grazia ("grace" or subtle ornament), underscoring the term's association with deliberate, appended strokes rather than inherent letter structure.[16] These linguistic developments postdate the visual origins of serifs in Roman inscriptional carving, where chisel techniques produced incidental terminals, but the nomenclature arose centuries later amid Renaissance and Enlightenment revivals of classical typography.[24]Classification and Evolution

Old-Style Serifs

Old-style serifs, also known as humanist or garalde typefaces, emerged in the late 15th century as the first movable-type interpretations of Renaissance humanism's revival of classical Roman inscriptional forms, characterized by moderate stroke contrast, diagonal stress axes, and bracketed serifs that curve gently into the main stems.[27] These features evoke the organic flow of hand-written Carolingian minuscule scripts and early chisel-cut stone letters, with head serifs often angled and lowercase 'e' counters featuring diagonal terminal bars in some designs.[28] Unlike later styles, old-style serifs exhibit low to moderate variation between thick and thin strokes, avoiding sharp transitions, which contributes to their warm, readable quality in extended text.[29] The foundational humanist old-style types originated with punchcutter Nicolas Jenson in Venice around 1470, whose roman faces featured subtle obliquity in curved strokes and softly bracketed serifs, bridging scribal traditions with mechanical reproduction.[30] This evolved into the garalde subgroup in 16th-century France, exemplified by Claude Garamond's designs from the 1530s to 1560s, which refined Jenson's model with even more fluid proportions, slanted crossbars on letters like 'e' and 'A', and italics derived from chancery cursive for enhanced legibility in book printing.[27] By the 17th century, Dutch and English variants, such as those by Christoffel van Dijck (active 1650s) and William Caslon (1730s), introduced slightly sharper details and the "Dutch taste" with condensed forms and higher x-heights, yet retained the core bracketed, low-contrast traits distinguishing them from transitional serifs' more vertical axes and refined uniformity.[31] Prominent 20th-century revivals include Stanley Morison's Garamond (1920s) for Monotype and Bruce Rogers' Centaur (1929), inspired by Jenson, which preserve these historical attributes for modern printing while adapting to industrial punchcutting precision.[4] Old-style serifs differ from transitional types, like Baskerville (1757), by maintaining greater obliquity in stroke modulation and less mechanical regularity, resulting in a handcrafted irregularity that enhances perceived warmth but demands careful spacing in digital rendering. Empirical typesetting studies from the era, such as those influencing Aldus Manutius's 1495 Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, confirm their efficacy for dense scholarly texts due to the serifs' role in guiding the eye along baseline flow without excessive visual noise.[32]Transitional Serifs

Transitional serifs represent an intermediate stage in the evolution of serif typefaces, emerging in the late 17th century as a refinement of old-style designs toward greater geometric precision and contrast. The style originated with the Romain du Roi, commissioned by Louis XIV in 1692 for the Imprimerie Royale and designed using mathematical grids by a committee led by Jacques Jaugeon, with cutting by Philippe Grandjean beginning in 1698; the type was first used in print in 1702 and completed by 1745.[33][34] This approach emphasized structured letterforms over calligraphic fluidity, reflecting Enlightenment ideals of rationality and order.[34] Key characteristics include moderate contrast between thick and thin strokes—greater than in old-style serifs but less extreme than in later Didone types—vertical or near-vertical stress in curved elements, horizontal head serifs, and bracketed serifs with flatter, more refined profiles and bases.[33][35] Larger x-heights and capitals aligning with ascender heights further distinguish the style, enhancing clarity on the page.[35] These features were enabled by advances in printing, such as smoother wove paper and denser inks, which allowed for finer details without blurring.[35] In the mid-18th century, English printer John Baskerville advanced the transitional style through his types cut around 1750–1757, introducing thinner hairlines, tapering serifs, and heightened contrast while maintaining bracketed forms.[33][34] French type designer Pierre-Simon Fournier contributed in the 1760s with systematic sizing and elegant, refined romans, as seen in his Manuel typographique.[4][35] Notable examples include Baskerville, Fournier, and 20th-century revivals like Times (1912), which adapt these traits for modern use.[4] The transitional category thus bridges the organic humanism of earlier serifs with the mechanical sharpness of neoclassical designs.[33][4]Didone and High-Contrast Serifs

Didone typefaces, also known as modern or neoclassical serifs, represent a genre characterized by extreme contrast between thick vertical strokes and thin horizontal hairlines, vertical axis stress, and serifs with minimal or no bracketing.[36][37] This high-contrast structure, including fine, unbracketed serifs, creates an elegant, geometric appearance influenced by Enlightenment-era neoclassicism and advances in printing technology that allowed for sharper impressions.[38][4] The style originated in France and Italy during the late 18th century as a departure from transitional serifs, drawing inspiration from pointed-nib writing and earlier high-contrast experiments like those of John Baskerville.[36][4] Firmin Didot first developed his influential Didot typeface between 1784 and 1811, cutting letters with pronounced stroke modulation and slim serifs for Parisian printing.[39] Concurrently, Italian printer Giambattista Bodoni refined similar designs, culminating in his Bodoni typeface around 1798, featuring even sharper contrasts and perpendicular serifs that emphasized classical proportion and clarity.[40][41] Didone serifs became the dominant general-purpose printing style throughout the 19th century, prized for their legibility in body text and decorative appeal in display applications, though the extreme contrasts later proved challenging for low-quality paper and ink spread.[38][42] High-contrast serifs in this family, often hairline-thin and abruptly terminating, enhanced the typeface's verticality and formality, aligning with the era's aesthetic shift toward rationalism and symmetry.[36][37]Slab Serifs

Slab serifs, also known as Egyptian or square serifs, feature thick, block-like extensions at the ends of letter strokes, with serifs that are unbracketed and typically equal in thickness to the main stems, creating a robust, monolithic appearance.[43][44] This design contrasts with thinner, more tapered serifs in other categories, emphasizing mechanical uniformity and boldness suitable for display purposes. The style emerged in the early 19th century amid the Industrial Revolution, with the first commercial slab serif, named "Antique," cut by London type founder Vincent Figgins around 1815 to meet demands for eye-catching advertising and signage type that could withstand the rigors of mass printing and street posting.[44][45] Initially monolinear with minimal stroke contrast, these faces drew inspiration from sign-painting practices and the era's fascination with Egyptian motifs following Napoleon's 1798–1801 campaign, though the "Egyptian" label is a misnomer unrelated to ancient scripts.[43][46] By the 1830s, slab serifs proliferated for their legibility at distance and durability in wood type for posters, supplanting earlier Didone styles in commercial printing.[47] Slab serifs subdivide into antique (humanist proportions with some organic variation), Clarendon (bracketed serifs, higher contrast, introduced 1845 by Robert Besley for body text emphasis), and geometric models (ultra-condensed, monoline forms evoking machinery).[43][48] Notable examples include Besley's Clarendon (1845), a refined ionic slab with curved brackets for hierarchy in newspapers; Rockwell (1934, Monotype), a geometric slab with even strokes for industrial aesthetics; and Memphis (1929, Stephenson Blake), an ultra-bold face for headlines.[49][50] Twentieth-century revivals, such as those in the 1990s by designers like Sumner Stone (Silica, 1993), integrated humanist elements for contemporary readability, adapting the style to digital interfaces and branding.[47]Other Specialized Styles

Clarendon typefaces, also known as Ionic in some classifications, constitute a specialized subset of slab serifs distinguished by bracketed serifs, moderate stroke contrast, and condensed proportions suitable for bold emphasis.[51] These features blend elements of 19th-century modern (Didone) serifs with the solidity of slab designs, resulting in a robust structure often used for headings, captions, or tabular data where readability at small sizes and visual weight are prioritized.[52] The style originated in England around 1845 when Robert Besley designed the first Clarendon, which was trademarked and became influential for its mechanical durability in printing presses during the industrial era.[53] Subsequent developments included greater variation in width and contrast, with examples like Ionic No. 5 exemplifying condensed forms for advertising and signage from the late 19th century onward.[54] Unlike uniform Egyptian slabs with unbracketed serifs, Clarendons incorporate subtle modulation akin to transitional serifs, enhancing legibility in dense text while maintaining a mechanical, high-contrast aesthetic.[55] Modern revivals, such as Adobe's Clarendon Text, adapt these traits for digital use, preserving the original's clarity and versatility across print and screen media.[56] Other niche serif styles include glyphic designs, where serifs taper to angular or triangular points evoking an engraved or chiseled appearance, as seen in typefaces like Albertus developed in the 1930s for display purposes.[57] These differ from traditional serifs by prioritizing inscriptional aesthetics over bracketed or slab forms, often featuring incised terminals that simulate stone carving, though they remain less common in body text due to reduced readability at smaller scales.[57] Inline variants, a decorative extension of modern serifs, incorporate internal white-space outlines within strokes for ornamental effects in titles and posters, emerging in the 19th century as specialized foundry offerings.[57]Design Principles

Serif Morphology and Variations

Serifs constitute the terminal embellishments on the primary strokes of letterforms in serif typefaces, typically manifesting as short perpendicular or angled projections that enhance visual continuity and structural definition. Morphologically, serifs are classified by their attachment to the stem: bracketed serifs feature a curved, gradual transition blending into the main stroke, as observed in traditional old-style faces, while unbracketed serifs connect abruptly at a right angle or sharp junction, common in slab designs.[58][59] In terms of shape, serifs exhibit variations including hairline serifs, which are thin and tapering extensions resembling fine lines; slab serifs, characterized by uniform, rectangular thickness providing a bold, block-like appearance; and wedge serifs, triangular in form that taper to a point, often imparting a sense of authority or emphasis.[60][61] These shapes can further differentiate by blunt, rounded, or pointed terminations, influencing the typeface's overall rhythm and optical weight.[59] Additional morphological distinctions include reflexive serifs, which introduce abrupt directional changes at the junction, contrasting with transitive serifs that maintain fluid continuity from the stem.[61] Serif morphology also varies by positional context, with top serifs on ascenders often lighter and bottom serifs on descenders or baselines potentially heavier to counter gravitational visual pull, ensuring balanced legibility across letterforms.[16]Technical Considerations in Type Design

In digital serif typeface design, glyphs are constructed as mathematical outlines using Bézier curves—cubic for PostScript Type 1 and OpenType PostScript formats, or quadratic for TrueType—to define the subtle contours of serifs, including their brackets, flares, and terminations.[62][63] This vector approach enables scalability without loss of detail but introduces challenges in maintaining proportional integrity across sizes, as minor discrepancies in curve control points can distort serif geometry during transformations.[64] Hinting instructions, embedded in the font file, are critical for serif designs to align stems, counters, and serifs to the pixel grid during rasterization, preventing irregularities in thin horizontal elements or the outright disappearance of fine serifs at small sizes (e.g., below 14 pixels).[65][66] High-contrast serif styles, such as Didone faces, amplify these issues, requiring stem hints, counter hints, and serif-specific adjustments to preserve intended contrast and rhythm on low-resolution displays.[65][67] Without such interventions, aliasing can render serifs as inconsistent blobs, particularly on Windows systems using grayscale rendering.[65] Spacing metrics demand precise sidebearings that incorporate serif overhangs, typically setting the left and right margins of round glyphs like 'o' to one-third of the counter width and adjusting linear glyphs like 'n' to 1.5 times that value for rhythmic evenness.[68][69] Kerning tables then fine-tune pairwise adjustments, addressing optical illusions from serif interactions—such as protrusions in 'A' and 'V' pairs or curved serifs in 'f' and 'i'—to avoid gapped or colliding appearances, with thousands of pairs often needed for comprehensive coverage.[70][68] In variable serif fonts, these metrics must interpolate smoothly across weights, complicating design as serifs thicken or taper non-linearly.[71] For screen optimization, designers incorporate subpixel rendering compatibility (e.g., ClearType), where hinting prioritizes horizontal stem alignment over vertical fidelity in serifs to enhance perceived sharpness, though this trades off some fidelity in transitional elements.[65] Empirical testing across devices ensures baseline alignment and x-height consistency, as serifs influence perceived metrics more than in sans-serif designs.[68]Readability and Legibility

Empirical Evidence from Print Studies

Miles A. Tinker’s comprehensive review of legibility studies conducted between 1927 and 1959, involving thousands of reading speed tests with college students, concluded that serif and sans-serif typefaces exhibit no inherent differences in readability for continuous print text under standard conditions, such as black ink on white paper at sizes of 10 to 14 points.[72] Factors like specific typeface design, line length (e.g., 12- to 14-pica widths), leading, and contrast proved more influential than serifs, with sans-serif examples such as Kabel Light matching or slightly exceeding serifs like Scotch Roman in speed-of-reading metrics (differences of -0.6% to +0.5%).[72] At smaller sizes, such as 6 points, serifs demonstrated a modest advantage (sans-serif legibility reduced by approximately 9.1%), attributed to serifs counteracting irradiation effects—visual blurring from ink spread on paper—but this benefit diminished sharply in low-contrast setups like white-on-black printing (serif legibility dropping 26.7%).[72] Subsequent empirical investigations have reinforced Tinker’s findings of negligible overall impact. A 2012 study with 238 native Cyrillic readers compared matched serif and sans-serif fonts from the same family in printed passages, measuring reading speed via timed comprehension tasks; results showed no statistically significant differences in either speed or text retention, challenging claims that serifs guide the eye or enhance flow in body text.[73] Similarly, controlled experiments varying serif prominence (0% to 10% of cap height) in five-letter strings and continuous print reading found minimal legibility gains at typical body-text sizes (e.g., thresholds around 3.14 arcminutes), with inter-letter spacing (e.g., 10% to 40% increases) yielding far greater improvements than serifs alone.[5] Newspaper-specific tests referenced by Tinker, using 7-point type on newsprint, further illustrated variability: sans-serif Opticon outperformed baseline serif Ionic No. 5 by 7.8% in legibility (p<0.01), while other sans-serifs like Textype showed insignificant gains (+2.2%), underscoring that optimized sans-serif designs can rival or surpass serifs in high-volume print applications.[72] Across these studies, comprehension and eye-movement data aligned with speed metrics, indicating serifs do not systematically reduce cognitive load or fatigue in print reading, contrary to anecdotal typographic lore. Empirical consensus prioritizes x-height consistency, stroke uniformity, and size over serif morphology for print legibility.[72][73][5]Screen and Digital Readability Data

A 2021 study examining reading speed among university students found no significant difference between the serif typeface Times New Roman and the sans-serif Calibri at 12-point size on digital screens, with mean speeds of 184.3 words per minute for Times New Roman and 185.4 words per minute for Calibri (t = 0.017, p = 0.301).[74] In contrast, on print, Times New Roman was read significantly faster (194.4 words per minute vs. 180.3 words per minute, p = 0.001), suggesting that screen-specific rendering may equalize performance across typeface categories.[74] Research on high-density displays, such as those exceeding 200 pixels per inch, indicates that legibility differences between serif and sans-serif fonts are minimal, challenging earlier preferences for sans-serif due to low-resolution screens (e.g., 60 PPI CRT monitors).[75] Empirical data from such studies show no substantial variance in reading speed, attributing past sans-serif advantages to pixelation artifacts that serifs exacerbate on low-DPI displays, rather than inherent readability deficits.[75] In e-book contexts, a referenced experiment reported higher reading comprehension scores with serif fonts like Times New Roman compared to sans-serif Arial, alongside subjective perceptions of serifs as less tiring, though preferences varied by demographics such as age and gender.[6] Screen-optimized serif fonts, such as Georgia, have demonstrated legibility on LCD displays comparable to sans-serif alternatives like Verdana in eye-tracking assessments, with performance tied more to font tuning for digital rendering than serif presence.[76] Overall, modern empirical evidence supports serif typefaces as viable for digital readability on high-resolution devices, with outcomes dependent on factors like point size, pixel density, and individual variability rather than categorical superiority.[75][74]Debunking Common Myths

One persistent claim holds that serif typefaces inherently improve readability for extended body text in print by guiding the reader's eye along the baseline or reducing visual fatigue, a notion often attributed to traditional book design practices. However, systematic reviews of empirical studies, including those measuring reading speed and eye-tracking data, find no consistent evidence supporting a superiority of serifs over sans-serifs in print legibility when controlling for variables like font size, x-height, and inter-letter spacing.[5] [77] For instance, a study varying serif size in lowercase fonts (0%, 5%, and 10% of cap height) showed only marginal legibility gains for small serifs, largely explained by the increased spacing serifs introduce rather than any directional "guiding" function.[5] This myth likely persists due to historical precedent in printed books, where serifs were standard, but fails under causal scrutiny as readability differences evaporate in matched comparisons.[78] Another misconception posits that serifs were developed primarily to prevent ink spreading or bleeding on early absorbent papers during letterpress printing, thereby enhancing clarity. In reality, serifs predate movable type by centuries, originating in ancient Roman monumental inscriptions where stone carvers added terminal strokes to refine chisel marks and impart a sense of completion to letterforms, as evidenced by surviving epigraphy from the 1st century BCE onward.[3] This inscriptional heritage was emulated in Renaissance punchcutting for metal type, not invented as a printing fix; early sans-serif experiments, like those in 19th-century signage, confirm serifs as stylistic rather than corrective.[79] Claims of ink-related origins lack primary sourcing and contradict the timeline, as blackletter and uncial scripts without serifs printed successfully before widespread Roman revival.[2] A related digital-era myth asserts that sans-serif fonts are categorically more legible on screens due to serifs causing pixelation or aliasing at low resolutions, rendering them unsuitable for web or UI text. While early raster displays (pre-2000s) amplified rendering artifacts for fine serif details, high-DPI screens and subpixel antialiasing have neutralized this; controlled experiments on e-readers and monitors show equivalent or context-dependent performance, with no typeface class dominating across body sizes from 10-14 points.[80] [6] For example, at larger sizes, serifs may even yield faster reading speeds in some digital formats, underscoring that legibility hinges on rendering quality and viewing distance over presence of serifs.[80] This view overstates obsolescent technology, ignoring how modern vector-based hinting equalizes both styles.[81] Finally, the idea that serif fonts hinder accessibility, particularly for dyslexic readers by creating visual "noise," lacks substantiation from randomized trials; guidelines from bodies like the APA emphasize that neither class is inherently inaccessible, with preferences varying individually rather than categorically.[82] Evidence from font legibility meta-analyses prioritizes clear stroke contrast and sufficient spacing over serif removal, debunking blanket avoidance as an unsubstantiated heuristic.[83]Usage Contexts and Impact

Traditional Print Applications

Serif typefaces emerged as the standard for body text in printed books following the adoption of roman designs in the late 15th century. Punchcutter Francesco Griffo created the first humanist roman typeface for Venetian printer Aldus Manutius around 1495, prominently featured in Pietro Bembo's De Aetna that same year, which served as a foundational model for subsequent serifs due to its clarity on the page.[84][85] French punchcutter Claude Garamond drew directly from this influence, producing his own roman types by the 1530s for works like editions of Erasmus, prioritizing even spacing and subtle serifs to facilitate sustained reading on absorbent paper stocks common in early printing.[86] In book printing, old-style serifs such as Garamond and later Baskerville, developed in the 1750s, were selected for their organic stroke modulation and bracketed serifs, which printers believed enhanced letter definition and horizontal flow in long passages, particularly under the limitations of metal type and ink spread.[9] These faces dominated literary and scholarly publications through the 19th century, with revivals continuing their use in fine press editions for their historical authenticity and perceived legibility in extended prose.[87] Newspapers traditionally employed transitional serifs to accommodate dense, multi-column layouts. Times New Roman, a serif designed by Stanley Morison and Victor Lardent, was commissioned by The Times of London in 1931 and first appeared in print on October 3, 1932, engineered for narrower measures with condensed forms and moderate contrast to fit more content while maintaining readability at small sizes on newsprint.[88][89] Similar transitional designs, including variants like Poynter, persisted in broadsheet journalism for body copy, valuing their efficiency in high-volume production over decorative flair.[90] Magazines and periodicals adopted serifs for feature articles and editorial content, mirroring book practices to evoke authority and ease prolonged engagement. Didone serifs, with high contrast, appeared in 19th-century titles for headlines, but body text favored more subdued old-style or transitional variants to counter the glare of coated stocks.[91] Slab serifs, introduced around 1815, found niche roles in bold display for advertisements and posters within print media, leveraging their mechanical robustness for larger formats.[92] ![Times New Roman sample.svg.png][center]Modern Digital and Branding Uses

In digital media, serif typefaces have seen renewed adoption since 2023 for headings, editorial content, and interfaces aiming to project sophistication, countering the dominance of sans-serifs which comprise about 85% of web fonts due to their clarity at small sizes on low-resolution displays.[93] Modern variants like DM Serif and Arvo emphasize open letterforms and subtle contrast for enhanced screen legibility, appearing in sites for luxury brands and financial sectors.[94][95] Typography trends through 2025 project continued serif integration in digital marketing, particularly condensed styles for "quiet luxury" aesthetics in headlines and calls-to-action, driven by higher-resolution screens mitigating historical readability concerns.[96][97] Empirical data on screen readability remains mixed: a 2022 study of e-book usability found serifs outperforming sans-serifs in comprehension and perceived ease, attributing benefits to contextual cues from strokes that guide eye movement.[6] In contrast, a 2025 review of accessibility guidelines reported sans-serifs yielding faster reading speeds and fewer errors, linked to simpler forms reducing visual noise on pixel-based renders.[98] High-density displays have largely debunked claims of inherent serif inferiority online, enabling their use in long-form web articles by outlets like The New York Times.[99] For branding, serifs dominate luxury logos—80% of fashion houses employ them to signal tradition and exclusivity over functional minimalism.[100] Gucci's bold serif logotype, introduced in variations since the 1960s but refined digitally in the 2020s, exemplifies this by associating the brand with enduring craftsmanship.[101] Similarly, Tiffany & Co. and Mercedes-Benz leverage elegant serifs like custom Didot derivatives for heritage conveyance, with studies attributing such choices to evoking trust via associations with print-era authority.[102] In 2024-2025 campaigns, condensed serifs appear in 70s-inspired revivals for apparel and finance, prioritizing perceptual sophistication over universal accessibility.[103][104]Analogues in Non-Latin Scripts

East Asian Adaptations

In East Asian typography, the Ming (also known as Song in Chinese contexts) style functions as the principal analogue to Western serif typefaces, employed across Chinese (Songti), Japanese (Mincho), and Korean (Myeongjo or Batang) scripts. These typefaces display pronounced stroke contrast, with horizontal elements thicker than verticals, and terminal flourishes or "little feet" at stroke ends that parallel the decorative projections of Latin serifs, enhancing visual flow and echoing calligraphic brush techniques where the brush's angle produces bolder horizontals.[105][106] The Songti form emerged from woodblock printing practices during China's Song dynasty (960–1279 CE), prioritizing sharp, reproducible character structures with angular terminals for clarity in mass-produced texts like imperial examinations and literature. Refinements occurred with metal movable type's adoption in the Yuan (1271–1368 CE) and Ming (1368–1644 CE) dynasties, yielding standardized designs that balanced aesthetic refinement—such as tapered, bracketed endings—with practical durability against ink spread on paper. In Japan, Mincho adaptations proliferated post-1868 Meiji Restoration, integrating Chinese influences with localized kana adjustments for newspapers and books, where the serif-like elements aided horizontal reading rhythms in mixed-script layouts. Korean Batang, a mincho-style typeface, applies similar features to Hangeul syllables, featuring bracketed serifs on strokes to maintain consistency in vertical and horizontal assemblies, as standardized in digital fonts by the 1990s for administrative and publishing needs.[107][108] Digital implementation of these adaptations initially struggled on low-resolution displays in the 1980s–1990s, as fine terminals blurred or aliased, favoring sans-serif Gothic alternatives for screen legibility in early computing and mobile interfaces across China, Japan, and Korea. Advances in rasterization and high-DPI screens by the 2010s enabled revivals, with variable-weight Songti and Mincho variants supporting responsive design; for instance, Microsoft's BatangChe font, released around 1992, optimized serif contrasts for Windows environments while preserving traditional stroke modulation. Contemporary iterations, like Adobe's Source Han Serif (2014 onward), extend pan-CJK compatibility with seven weights, adapting historical serif analogues for multilingual web and print without diluting causal links to brush-derived forms.[105][108][109]Thai and Indic Influences