Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Rustic capitals

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2009) |

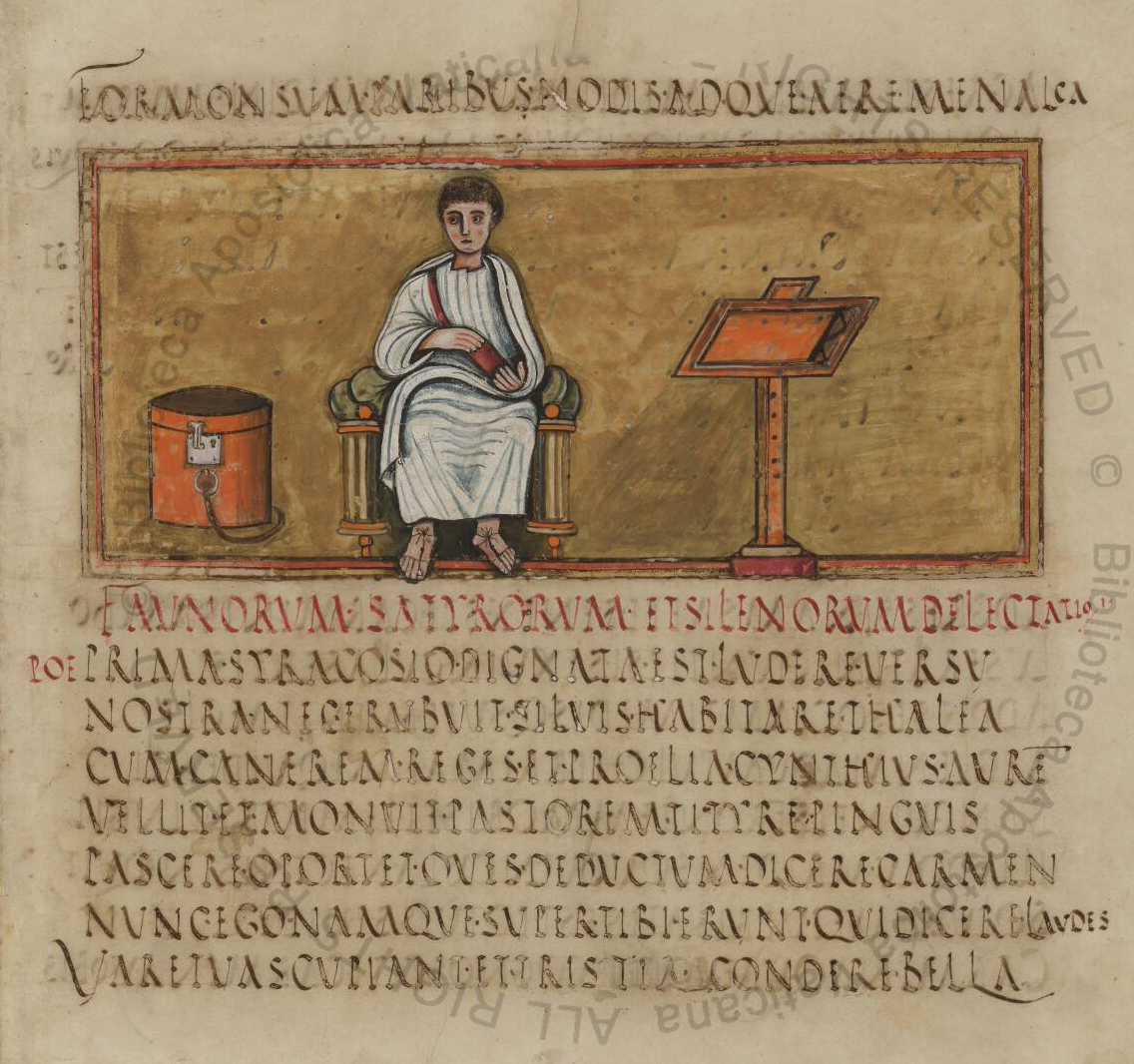

Rustic capitals (Latin: littera capitalis rustica) is an ancient Roman calligraphic script. Because the term is negatively connoted supposing an opposition to the more 'civilized' form of the Roman square capitals, Bernhard Bischoff prefers to call the script canonized capitals. The script was used for writing secular texts.[1]

History

[edit]

The script was used between the 1st century and the 9th century, most often between the 4th and 6th centuries. After the 5th century, rustic capitals began to fall out of use, but they continued to be used as a display script in titles and headings, along with uncial as the script of the main text.

Structure

[edit]Rustic capitals are similar to Roman square capitals, but are less rigid, influenced more by pen and ink writing on papyrus or parchment. The letters are thinner and more compressed, use many more curved lines than do square capitals, and have descenders extending below the baseline.

Surviving works

[edit]

About fifty manuscripts with rustic capitals survive, including four copies of works by Virgil (including the Vergilius Vaticanus and the Vergilius Romanus), one copy of a work by Terence, and one of a work by Prudentius. The script was usually used for de luxe copies of pagan authors; the only works by Christian authors which use this script are those by Prudentius and Sedulius.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hamel, Christopher de (2016). Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts. Penguin Books Limited. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-241-00309-1.

External links

[edit]- 'Manual of Latin Palaeography' (A comprehensive PDF file containing 82 pages profusely illustrated, 6th edition, January 2024).