Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

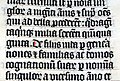

Beneventan script

View on Wikipedia

The Beneventan script was a medieval script that originated in the Duchy of Benevento in southern Italy. In the past it has also been called Langobarda, Longobarda, Longobardisca (signifying its origins in the territories ruled by the Lombards), or sometimes Gothica; it was first called Beneventan by palaeographer E. A. Lowe.

It is mostly associated with Italy south of Rome, but it was also used in Beneventan-influenced centres across the Adriatic Sea in Dalmatia. The script was used from approximately the mid-8th century until the 13th century, although there are examples from as late as the 16th century. There were two major centres of Beneventan usage: the monastery on Monte Cassino, and Bari. The Bari type developed in the 10th century from the Monte Cassino type; both were based on Roman cursive as written by the Langobards. In general the script is very angular. According to Lowe, the perfected form of the script was used in the 11th century, while Desiderius was abbot of Monte Cassino, declining thereafter.

Features

[edit]Beneventan features many ligatures and "connecting strokes" – the letters of a word could be joined together by a single line, with forms almost unrecognizable to a modern eye.[1]

Ligatures may be obligatory as: ⟨ei⟩, ⟨gi⟩, ⟨li⟩, ⟨ri⟩ and ⟨ti⟩ (two different forms: ti-dura where t had kept the t sound and ti-assibilata where t had taken the vulgar ts sound). They may be optional: frequent as ⟨et⟩, ⟨ae⟩ and ⟨st⟩; or rare as ⟨ta⟩, ⟨to⟩ and ⟨xp⟩.[2] Ligatures involving the letter ⟨t⟩ resemble late New Latin Cursive as in the Merovingian and Visigothic,[2] exception made for peculiar ⟨st⟩ ligature where ⟨s⟩ is connected to ⟨t⟩ on top influencing later on the German pre-caroline script and all the script from this derived until nowadays.[3] In ligatures ⟨t⟩ can take many forms depending on the letter joined to it. Ligatures with the letters ⟨e⟩ and ⟨r⟩ are also common. In early forms of Beneventan, the letter ⟨a⟩ has an open top, similar to the letter ⟨u⟩; later, it resembled "cc" or "oc", with long tails hanging to the right. In the Bari type, the letter ⟨c⟩ often has a "broken" form, resembling the Beneventan form of the letter ⟨e⟩. However, ⟨e⟩ itself has a very long middle arm, distinguishing it from ⟨c⟩. The letter ⟨d⟩ can have a vertical or left-slanting ascender, the letter ⟨g⟩ resembles the uncial form, and the letter ⟨i⟩ is very tall and resembles ⟨l⟩.

The script has a unique way to signify abbreviations both by omission and contraction – like most other Latin scripts, missing letters can be signified by a macron over the previous letter, although Beneventan often adds a dot to the macron. There is also a symbol resembling the digit ⟨3⟩, or a sideways ⟨m⟩, when the letter ⟨m⟩ has been omitted. In other scripts there is often little or no punctuation, but standard punctuation forms were developed for the Beneventan script, including the basis for the modern question mark.

Beneventan shares some features with Visigothic and Merovingian script, probably due to the common late Roman matrix.

References

[edit]- ^ Hudson, John. "The Beneventan Memory". Tiro Typeworks. Retrieved 25 August 2025.

- ^ a b The Scriptorium and Library at Monte Cassino, 1058-1105, Francis Newton

- ^ Fonts for latin paleography, 4th ed., Juan-José Marcos

Further reading

[edit]- Francesco Bianchi/Antonio Magi Spinetti: BMB. Bibliografia dei manoscritti in scrittura Beneventana, Rom 1993 ff.

- Giulio Battelli: Beneventana, scritture e miniatura, in: Enciclopedia Cattolica II, Città del Vaticano 1949, p. 1617-1618.

- Virginia Brown: A second new list of beneventan manuscripts, in: Studi medievali 40 (1978), p. 239-289

- Guglielmo Cavallo: Rotoli di Exultet dell'Italia meridionale, Bari 1973.

- Guglielmo Cavallo: Struttura e articolazione della minuscola beneventana tra i secoli X – XII, in: Studi medievali 3. ser. 11 (1970), p. 343-368.

- Alfonso Gallo: Contributo allo studio delle scritture meridionali nell'alto medio evo, in: Bulletino dell'Istituto Storico Italiano 47 (1931), S. 333-350.

- Elias Avery Lowe: The Beneventan Script. A history of the south Italian Minuscule, Oxford 1914.

- Elias Avery Lowe: Scriptura beneventana. A history of the South Italian minuscule, 2 vol., Oxford 1929.

- Elias Avery Lowe: A new list of beneventan manuscripts. In: Collectanea Vaticana in honorem A. M. card. Albareda, Città del Vaticano1962 (Studi e testi 220), p. 211-244 = ders., Palaographical Papers II, Oxford 1972, p. 417-479.

- Elias Avery Loew [=Lowe]: The Beneventan Script, 2 Bde., 2. Aufl., Rom 1978 - 1980.

- Francis Newton: Fifty Years of Beneventan Studies, in: AfD 50 (2004), p. 327-346.

- Viktor Novak: Scriptura Beneventana, Zagreb 1920

External links

[edit]- 'Fonts for Latin Paleography: User's Manual. 6th edition' A manual of Latin paleography; a comprehensive PDF file containing 82 pages profusely illustrated, 4 January 2024).

- Bibliography of beneventan manuscripts