Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

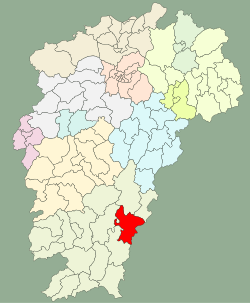

Ruijin

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2017) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (May 2022) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Key Information

| Ruijin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 瑞金 | ||||||||

| Postal | Juicheng | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Ruijin (Chinese: 瑞金; pinyin: Ruìjīn) is a county-level city of Ganzhou in the mountains bordering Fujian Province in the south-eastern part of Jiangxi Province. Formerly a county, Ruijin became a county-level city on May 18, 1994.

It was an early center of Chinese communist activity and developed a reputation as cradle of the Chinese Communist Revolution.[1]: 94 In the late-1920s, the Nationalists forced the Communists out of the Jinggang Mountains, sending them fleeing to Ruijin and the safety of its relative isolation in the rugged mountains along Jiangxi-Fujian border. In 1931, Mao Zedong founded the Chinese Soviet Republic (CSR) with Ruijin as its capital; it was called Ruijing by the CSR. The Communists withdrew in 1934 on the Long March after being surrounded again by the Nationalists.[citation needed]

During the Cultural Revolution, the Ruijin Massacre in September and October 1968 killed over 300 people in the county.

Ruijin is a popular destination for red tourism and ecotourism. It is a pilgrimage for Maoists from China and around the globe.

Administrative divisions

[edit]Ruijin City has 7 towns and 10 townships.[2]

- 7 Towns

|

|

- 10 Townships

|

|

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Ruijin, elevation 290 m (950 ft), (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.9 (82.2) |

31.2 (88.2) |

32.8 (91.0) |

34.1 (93.4) |

35.8 (96.4) |

37.5 (99.5) |

40.4 (104.7) |

39.7 (103.5) |

37.4 (99.3) |

36.4 (97.5) |

33.5 (92.3) |

27.9 (82.2) |

40.4 (104.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.5 (56.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

25.2 (77.4) |

28.9 (84.0) |

31.4 (88.5) |

34.3 (93.7) |

33.7 (92.7) |

31.0 (87.8) |

26.8 (80.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

15.9 (60.6) |

24.8 (76.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.6 (47.5) |

11.2 (52.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

20.2 (68.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

26.7 (80.1) |

28.9 (84.0) |

28.2 (82.8) |

25.7 (78.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

15.7 (60.3) |

10.2 (50.4) |

19.6 (67.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.3 (41.5) |

7.8 (46.0) |

11.2 (52.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.5 (76.1) |

21.9 (71.4) |

16.8 (62.2) |

11.6 (52.9) |

6.3 (43.3) |

15.9 (60.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −5.2 (22.6) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

4.8 (40.6) |

11.4 (52.5) |

15.0 (59.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

12.5 (54.5) |

4.2 (39.6) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 76.7 (3.02) |

103.8 (4.09) |

199.6 (7.86) |

192.3 (7.57) |

263.0 (10.35) |

268.3 (10.56) |

139.6 (5.50) |

157.4 (6.20) |

76.9 (3.03) |

47.7 (1.88) |

67.8 (2.67) |

55.1 (2.17) |

1,648.2 (64.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 10.8 | 12.8 | 18.8 | 17.0 | 18.0 | 17.5 | 12.5 | 15.1 | 9.2 | 6.0 | 8.1 | 8.4 | 154.2 |

| Average snowy days | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 1.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79 | 80 | 82 | 79 | 80 | 80 | 73 | 76 | 77 | 75 | 77 | 76 | 78 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 85.6 | 85.2 | 76.6 | 101.4 | 119.0 | 132.3 | 217.9 | 196.7 | 163.4 | 158.3 | 132.4 | 123.4 | 1,592.2 |

| Percentage possible sunshine | 26 | 27 | 21 | 27 | 29 | 32 | 52 | 49 | 45 | 45 | 41 | 38 | 36 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[3][4] | |||||||||||||

Transport

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Chatwin, Jonathan (2024). The Southern Tour: Deng Xiaoping and the Fight for China's Future. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781350435711.

- ^ "南京市-行政区划网" (in Chinese). XZQH. Retrieved 2012-05-24.

- ^ 中国气象数据网 – WeatherBk Data (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "Experience Template" 中国气象数据网 (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "Sinkhole swallows four cars in China". BBC News.