Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

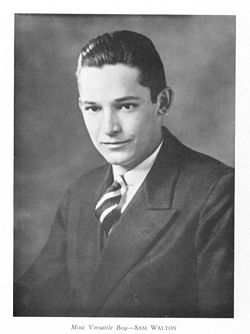

Sam Walton

View on Wikipedia

Samuel Moore Walton (March 29, 1918 – April 5, 1992) was an American business magnate best known for co-founding the retailers Walmart and Sam's Club, which he started in Rogers, Arkansas, and Midwest City, Oklahoma, in 1962 and 1983 respectively. Wal-Mart Stores Inc. grew to be the world's largest corporation by revenue as well as the biggest private employer in the world.[1] For a period of time, Walton was the richest person in the United States.[2] His family has remained the richest family in the U.S. for several consecutive years, with a net worth of around $440.6 billion US as of January 2025. In 1992 at the age of 74, Walton died of blood cancer and was buried at the Bentonville Cemetery in his longtime home of Bentonville, Arkansas.

Key Information

Early life

[edit]Samuel Moore Walton was born to Thomas Gibson Walton and Nancy Lee, in Kingfisher, Oklahoma. He lived there with his parents on their farm until they moved in 1923. However, farming did not provide enough money to raise a family, and Thomas Walton went into farm mortgaging. He worked for his brother's Walton Mortgage Company, which was an agent for Metropolitan Life Insurance,[3][4] where he foreclosed on farms during the Great Depression.[5]

He and his family (now with another son, James, born in 1921) moved from Oklahoma. They moved from one small town to another for several years, mostly in Missouri. While attending eighth grade in Shelbina, Missouri, Sam became the youngest Eagle Scout in the state's history.[6] In adult life, Walton became a recipient of the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award from the Boy Scouts of America.[7]

Eventually the family moved to Columbia, Missouri. Growing up during the Great Depression, he did chores to help make financial ends meet for his family as was common at the time. He milked the family cow, bottled the surplus, and drove it to customers. Afterwards, he would deliver Columbia Daily Tribune newspapers on a paper route. In addition, he sold magazine subscriptions.[8] Upon graduating from David H. Hickman High School in Columbia, he was voted "Most Versatile Boy".[9]

After high school, Walton decided to attend college, hoping to find a better way to help support his family. He attended the University of Missouri as an ROTC cadet. During this time, he worked various odd jobs, including waiting tables in exchange for meals. Also during his time in college, Walton joined the Zeta Phi chapter of Beta Theta Pi fraternity. He was also tapped by QEBH, the well-known secret society on campus honoring the top senior men, and the national military honor society Scabbard and Blade. Additionally, Walton served as president of Burall Bible Class, a large class of students from the University of Missouri and Stephens College.[10] Upon graduating in 1940 with a bachelor's degree in economics, he was voted "permanent president" of the class.[11]

Furthermore, he elaborated that he learned from a very early age that it was important for them as kids to help provide for the home, to be givers rather than takers. Walton realized while (later) serving in the army, that he wanted to go into retailing and to go into business for himself.[12]

Walton joined J. C. Penney as a management trainee in Des Moines, Iowa,[11] three days after graduating from college.[8] This position paid him $75 a month. Walton spent approximately 18 months with J. C. Penney.[13] He resigned in 1942 in anticipation of being inducted into the military for service in World War II.[8] In the meantime, he worked at a DuPont munitions plant near Tulsa, Oklahoma. Soon afterwards, Walton joined the military in the U.S. Army Intelligence Corps, supervising security at aircraft plants. In this position he served at Fort Douglas in Salt Lake City, Utah.[citation needed] He eventually reached the rank of captain.

The first stores

[edit]In 1945, after leaving the military, Walton took over management of his first variety store at the age of 26.[14] With the help of a $20,000 loan ($349,316 in 2024) from his father-in-law, Leland Robson, plus $5,000 ($87,329 in 2024) he had saved from his time in the Army, Walton purchased a Ben Franklin variety store in Newport, Arkansas.[8] The store was a franchise of the Butler Brothers chain.

Walton pioneered many concepts that became crucial to his success. According to Walton, if he offered prices as good as or better than stores in cities that were four hours away by car, people would shop at home.[15] Walton ensured the shelves were consistently stocked with a wide range of goods. His second store, the tiny "Eagle" department store, was down the street from his first Ben Franklin and next door to its main competitor in Newport.

With the sales volume growing from $80,000 to $225,000 in three years, Walton drew the attention of the landlord, P. K. Holmes, whose family had a history in retail.[16] Admiring Sam's great success and desiring to reclaim the store and franchise rights for his son, he refused to renew the lease. The lack of a renewal option, together with the prohibitively high rent of 5% of sales, were early business lessons to Walton. Despite forcing Walton out, Holmes bought the store's inventory and fixtures for $50,000, which Walton called "a fair price".[17]

With a year left on the lease, but the store effectively sold, Walton, his wife, Helen, and his father-in-law managed to negotiate the purchase of a new location on the downtown square of Bentonville, Arkansas. Walton negotiated the purchase of a small discount store, and the title to the building, on the condition that he get a 99-year lease to expand into the shop next door. The owner of the shop next door refused six times, and Walton had all but given up on Bentonville when his father-in-law, without Sam's knowledge, paid the shop owner a final visit and $20,000 to secure the lease. He had just enough left from the sale of the first store to close the deal and reimburse Helen's father. They opened for business with a one-day remodeling sale on May 9, 1950.[16]

Before he bought the Bentonville store, it was doing $72,000 in sales, and it increased to $105,000 in the first year, then $140,000 and $175,000.[18]

A chain of Ben Franklin stores

[edit]With the new Bentonville "Five and Dime" opening for business and, 220 miles (350 kilometers) away, a year left on the lease in Newport, the money-strapped young Walton had to learn to delegate responsibility.[19][20]

After succeeding with two stores at such a distance (and with the postwar baby boom in full effect), Walton became enthusiastic about scouting more locations and opening more Ben Franklin franchises. (Also, having spent countless hours behind the wheel, and with his close brother James "Bud" Walton having been a pilot in the war, he decided to buy a small second-hand airplane. Both he and his son John would later become accomplished pilots and log thousands of hours scouting locations and expanding the family business.).[19]

In 1954, he opened a store with Bud in a shopping center in Ruskin Heights, a suburb of Kansas City, Missouri. With the help of his brother and father-in-law, Sam went on to open many new variety stores. He encouraged his managers to invest and take an equity stake in the business, often as much as $1000 in their store, or the next outlet to open. (This motivated the managers to sharpen their managerial skills and take ownership over their role in the enterprise.)[19] By 1962, along with his brother Bud, he owned 16 stores in Arkansas, Missouri, and Kansas (fifteen Ben Franklins and one independent, in Fayetteville).[21]

First Walmart

[edit]The first true Walmart opened on July 2, 1962, in Rogers, Arkansas.[22] Called the Wal-Mart Discount City store, it was located at 719 West Walnut Street, and launched a determined effort to market American-made products. Included in the effort was a willingness to find American manufacturers who could supply merchandise for the entire Walmart chain at a price low enough to meet the foreign competition.[23]

As the Meijer store chain grew, it caught the attention of Walton. He came to acknowledge that his one-stop-shopping center format was based on Meijer's original innovative concept.[24] Contrary to the prevailing practice of American discount store chains, stores were located in smaller towns, not larger cities. To be near consumers, the only option at the time was to open outlets in small towns. The model offered two advantages. First, existing competition was limited and secondly, if a store was large enough to control business in a town and its surrounding areas, other merchants would be discouraged from entering the market.[15]

To make his model work, he emphasized logistics, particularly locating stores within a day's drive of Walmart's regional warehouses, and distributed through its own trucking service. Buying in volume and efficient delivery permitted sale of discounted name brand merchandise. Thus, sustained growth—from 1977's 190 stores to 1985's 800—was achieved.[11]

Given its scale and economic influence, Walmart is noted to significantly impact any region where it establishes a store. These impacts, both positive and negative, have been dubbed the "Walmart Effect".[25]

Personal life

[edit]Walton married Helen Robson on Valentine's Day, February 14, 1943.[8] They had four children: Samuel Robson (Rob) born in 1944, John Thomas (1946–2005), James Carr (Jim) born in 1948, and Alice Louise born in 1949.[26]

Walton supported various charitable causes. He and Helen were active in 1st Presbyterian Church in Bentonville;[27] Sam served as an Elder and a Sunday School teacher, teaching high school age students.[28] The family made substantial contributions to the congregation. Walton worked the concept of “service leadership” into the corporate structure of Walmart based on the concept of Christ being a servant leader and emphasized the importance of serving others based in Christianity.[29]

Health issues and death

[edit]In 1982, Walton was diagnosed and treated for Hairy cell leukemia. He was diagnosed with bone cancer in 1990 and had gone through radiation therapy and chemotherapy at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas.[30] Walton died on Sunday, April 5, 1992, a week after his 74th birthday, of multiple myeloma, a type of blood cancer,[31] in Little Rock, Arkansas.[32] A few days earlier, according to his son, Walton was still reviewing sales data in his hospital bed.[33] The news of his death was relayed by satellite to all 1,960 Walmart stores.[34] At the time, his company employed 400,000 people. Annual sales of nearly $50 billion flowed from 1,735 Walmarts, 212 Sam's Clubs, and 13 Supercenters.[11]

His remains are interred at the Bentonville Cemetery. He left his ownership in Walmart to his wife and their children: Rob Walton succeeded his father as the Chairman of Walmart, and John Walton was a director until his death in a 2005 plane crash. The others are not directly involved in the company (except through their voting power as shareholders), however his son Jim Walton is chairman of Arvest Bank. The Walton family held five spots in the top ten richest people in the United States until 2005. Two daughters of Sam's brother Bud Walton — Ann Kroenke and Nancy Laurie — hold smaller shares in the company.[35]

Legacy

[edit]

In 1998, Walton was included in Time's list of 100 most influential people of the 20th Century.[36] Walton was honored for his work in retail in March 1992, just one month before his death, when he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from then-President George H. W. Bush.[34]

Forbes ranked Sam Walton as the richest person in the United States from 1982 to 1988, ceding the top spot to John Kluge in 1989 when the editors began to credit Walton's fortune jointly to him and his four children.[37] (Bill Gates first headed the list in 1992, the year Walton died.) Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. also runs Sam's Club warehouse stores.[38] Walmart operates in the United States and in more than fifteen international markets, including: Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, India, South Africa, Botswana, Ghana, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Kenya, Lesotho, Eswatini (Swaziland), Honduras, Japan, Mexico, Nicaragua and the United Kingdom.[39]

At the University of Arkansas, the Business College (Sam M. Walton College of Business) is named in his honor. Walton was inducted into the Junior Achievement U.S. Business Hall of Fame in 1992.[40]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Sam Walton Biography". 7infi.com. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved August 10, 2017.

- ^ Harris, Art (November 17, 1985). "America's Richest Man Lives...Here?Sam Walton, Waiting in Line At the Wal-Mart With Everybody Else". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ Walton, Sam (2012). Sam Walton: Made in America. Random House Publishing Group. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-345-53844-4.

- ^ Lee, Sally (2007). Sam Walton: Business Genius of Wal-Mart. Enslow Publishers, Inc. p. 13. ISBN 978-0766026926. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ Landrum, Gene N. (2004). Entrepreneurial Genius: The Power of Passion. Brendan Kelly Publishing. p. 120. ISBN 1895997232. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ Townley, Alvin (December 26, 2006). Legacy of Honor: The Values and Influence of America's Eagle Scouts. Asia: St. Martin's Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 0-312-36653-1. Archived from the original on December 19, 2006. Retrieved December 29, 2006.

- ^ "Distinguished Eagle Scouts" (PDF). Scouting.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 12, 2016. Retrieved November 4, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Gross, Daniel; Forbes Magazine Staff (August 1997). Greatest Business Stories of All Time (First ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sonsf. p. 269. ISBN 0-471-19653-3. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ "Sam and Bud Walton". SHSMO Historic Missourians. Retrieved February 1, 2024.

- ^ Walton, Sam (2012). Sam Walton: Made in America. Random House Publishing Group. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-345-53844-4.

- ^ a b c d "Sam Walton". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2012. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ Walton, Sam (1992). Sam Walton, Made in America: My Story. Doubleday. pp. 5, 15, and 20.

- ^ Walton, Sam (2012). Sam Walton: Made in America. Random House Publishing Group. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-345-53844-4.

- ^ "Lessons from Sam Walton: How a social-local strategy brings the human touch back to business". Hearsay Systems. June 4, 2012. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Sandra S. Vance, Roy V. Scott (1994). Wal-Mart. New York: Twayne Publishers. p. 41. ISBN 0-8057-9833-1.

- ^ a b "Sam Walton". Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ Walton & Huey, Made in America: My Story, p. 30.

- ^ Wenz, Peter S. (2012). Take Back the Center: Progressive Taxation for a New Progressive Agenda. MIT Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0262017886. Retrieved December 30, 2012.

- ^ a b c Walton, Sam; John Huey (1992). Made in America: My Story. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-42615-1.

- ^ Trimble, Vance H. (1991). Sam Walton: the Inside Story of America's Richest Man. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-451-17161-6. ISBN 978-0-451-17161-0

- ^ Kavita Kumar (September 8, 2012). "Ben Franklin store, a throwback to the five-and-dime, finally closes". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on August 30, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2014.

- ^ Gross, Daniel; Forbes Magazine Staff (1997). Greatest Business Stories of All Time (First ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 272. ISBN 0-471-19653-3.

- ^ Yohannan T. Abraham; Yunus Kathawala; Jane Heron (December 26, 2006). "Sam Walton: Walmart Corporation". The Journal of Business Leadership, Volume I, Number 1, Spring 1988. American National Business Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on January 20, 2002. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ "Fred Meijer, West Michigan billionaire grocery magnate, dies at 91". MLive.com. November 26, 2011. Archived from the original on April 10, 2018. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- ^ Fishman, Charles (2006). How The World's Most Powerful Company Really Works – and How It's Transforming the American Economy. New York: The Penguin Press, Inc.

- ^ Tedlow, Richard S. (July 23, 2001). "Sam Walton: Great From the Start". Working Knowledge. Harvard Business School. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- ^ Hodges, Sam (April 20, 2007). "Presbyterian obit on Wal-Mart founder's widow". The Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ Robert Frank (July 25, 2009). "Nickel and Dimed". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 21, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ Walsh, Colleen (November 19, 2009). "God and Walmart". Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ Hayes, Thomas (April 6, 1992). "Sam Walton Is Dead At 74; the Founder Of Wal-Mart Stores". The New York Times. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ Walton, Sam (1993). Sam Walton: Made in America. Bantam Books. p. 329. ISBN 0-553-56283-5.

- ^ Ortega, Bob. "In Sam We Trust: The Untold Story of Sam Walton and How Wal-Mart Is Devouring America". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 9, 2005. Retrieved February 7, 2007.

- ^ Fishman, Charles (2006). The Wal-Mart Effect. New York, NY: Penguin Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-14-303878-8.

His oldest son said Walton was reviewing store-level sales data, in his hospital bed, days before he died.

- ^ a b Gross, Daniel; Forbes Staff (August 1997). Greatest Business Stories of All Time (First ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 283. ISBN 0-471-19653-3.

- ^ "Ann Walton Kroenke". Forbes. Archived from the original on July 27, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ^ "Time 100 Builders & Titans: Sam Walton". Time Magazine. December 7, 1998. Archived from the original on October 18, 2000. Retrieved March 31, 2012. at Wayback Machine

- ^ Clare O'Connor (September 9, 2010). "Billionaire John Kluge Dies At 96". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 20, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2017.

- ^ "Walmart's test store for new technology, Sam's Club Now, opens next week in Dallas". TechCrunch. October 29, 2018. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ International Operations Data Sheet Archived January 11, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Walmart Corporation, July 2009.

- ^ Patty de Llosa and Jessica Skelly von Brachel (March 23, 1992). "The National BUSINESS HALL OF FAME". Fortune. Peter Nulty Reporter Associates. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved May 25, 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Trimble, Vance H. (1991). Sam Walton: the Inside Story of America's Richest Man. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-451-17161-0.

- Walton, Sam; John Huey (1992). Made in America: My Story. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-42616-X.

Further reading

[edit]- Bianco, Anthony (2006). The Bully of Bentonville: how the high cost of Wal-Mart's everyday low prices is hurting America. New York: Currency/Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-51356-9.

- Scott, Roy Vernon; Vance, Sandra Stringer (1994). Wal-Mart: A History of Sam Walton's Retail Phenomenon. Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0-8057-9833-1.

- Fishman, C. (2006). The Wal-Mart Effect: How the World's Most Powerful Company Really Works – and HowIt's Transforming the American Economy. Penguin.

- Marquard, W. H. (2007). Wal-Smart: What it really takes to profit in a Wal-Mart world. McGraw Hill Professional.

- Sam Walton, Bibliography.

External links

[edit]- "Time 100 Builders & Titans: Sam Walton by John Huey". Time Magazine. December 7, 1998. Archived from the original on October 18, 2000. Retrieved March 31, 2012. at Wayback Machine

- Week Sam Walton: The King of the Discounters August 8, 2004

- Sam M. Walton College of Business, University of Arkansas Archived May 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Sam Walton at Find a Grave

- Voices of Oklahoma interview, Chapters 12–16, with Frank Robson. First person interview conducted on November 2, 2009, with Frank Robson, brother-in-law of Sam Walton.

.jpg/250px-Sam_Walton_(1992_2).jpg)

.jpg)