Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

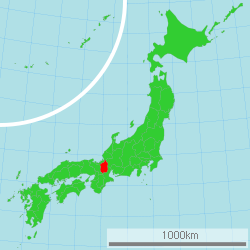

Shiga Prefecture

View on WikipediaShiga Prefecture (滋賀県, Shiga-ken; Japanese pronunciation: [ɕiꜜ.ɡa, -ŋa, ɕi.ɡaꜜ.keɴ, -ŋaꜜ.keɴ][2]) is a landlocked prefecture of Japan in the Kansai region of Honshu.[3] Shiga Prefecture has a population of 1,398,972 as of 1 February 2025 and has a geographic area of 4,017 km2 (1,551 sq mi). Shiga Prefecture borders Fukui Prefecture to the north, Gifu Prefecture to the northeast, Mie Prefecture to the southeast, and Kyoto Prefecture to the west.

Key Information

Ōtsu is the capital and largest city of Shiga Prefecture, with other major cities including Kusatsu, Nagahama, and Higashiōmi.[4] Shiga Prefecture encircles Lake Biwa, the largest freshwater lake in Japan, and 37% of the total land area is designated as Natural Parks, the highest of any prefecture. Shiga Prefecture's southern half is located adjacent to the former capital city of Kyoto and forms part of Greater Kyoto, the fourth-largest metropolitan area in Japan. Shiga Prefecture is home to Ōmi beef, the Eight Views of Ōmi, and Hikone Castle, one of four national treasure castles in Japan.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Shiga was known as Ōmi Province or Gōshū before the prefectural system was established.[5] Omi was a neighbor of Nara and Kyoto, at the junction of western and eastern Japan. During the period 667 to 672, Emperor Tenji founded a palace in Otsu. In 742, Emperor Shōmu founded a palace in Shigaraki. In the early Heian period, Saichō was born in the north of Otsu and founded Enryaku-ji, the center of Tendai and a UNESCO World Heritage Site and monument of Ancient Kyoto now.

During the Heian period, the Sasaki clan ruled Omi, and afterward, the Rokkaku clan, Kyōgoku clan, and Azai clans ruled Omi. While during the Azuchi-Momoyama period, Oda Nobunaga subjugated Omi and built Azuchi Castle on the eastern shores of Lake Biwa in 1579. Tōdō Takatora, Gamō Ujisato, Oichi, Yodo-dono, Ohatsu, and Oeyo were Omi notables during this period.

In 1600, Ishida Mitsunari, born in the east of Nagahama and based in Sawayama Castle, made war against Tokugawa Ieyasu in Sekigahara, Gifu. After the battle, Ieyasu made Ii Naomasa a new lord of Sawayama. Naomasa established the Hikone Domain, later known for Ii Naosuke. Ii Naosuke became the Tokugawa shogunate's Tairō and concluded commercial treaties with the Western powers and thus ended Japan's isolation from the world in the 19th century. Besides the Hikone Domain, many domains ruled Omi such as Zeze.

With the abolition of the han system, eight prefectures were formed in Omi. They were unified into Shiga Prefecture in September 1872. "Shiga Prefecture" was named after "Shiga District" because Otsu belonged to the district until 1898. From August 1876 to February 1881, southern Fukui Prefecture had been incorporated into Shiga Prefecture.

In 2015, Shiga Governor Taizō Mikazuki conducted a survey asking citizens whether they felt it necessary to change the name of the prefecture, partly to raise its profile as a destination for domestic tourism.[6]

Geography

[edit]

Shiga borders Fukui Prefecture in the north, Gifu Prefecture in the east, Mie Prefecture in the southeast, and Kyoto Prefecture in the west.

Lake Biwa, Japan's largest, is located at the center of this prefecture. It occupies one-sixth of its area. The Seta River flows from Lake Biwa to Osaka Bay through Kyoto. This is the only natural river that flows out from the lake. Most other natural rivers flow into the lake. There were many lagoons around Lake Biwa, but most of them were reclaimed in 1940s. One of the preserved lagoons is the wetland (水郷, suigō) in Omihachiman, and it was selected as the first Important Cultural Landscapes in 2006.

The lake divides the prefecture into four different areas: Kohoku (湖北; north of lake) centered Nagahama, Kosei (湖西; west of lake) centered Imazu, Kotō (湖東; east of lake) centered Hikone and Konan (湖南; south of lake) centered Otsu.

Plains stretch to the eastern shore of Lake Biwa. The prefecture is enclosed by mountain ranges with the Hira Mountains and Mount Hiei in the west, the Ibuki Mountains in the northeast, and the Suzuka Mountains in the southeast. Mount Ibuki is the highest mountain in Shiga. In Yogo, a small lake known for the legend of the heavenly robe of an angel (天女の羽衣, tennyo no hagoromo), which is similar to a western Swan maiden.[7]

Shiga's climate sharply varies between north and south. Southern Shiga is usually warm, but northern Shiga is typically cold with high snowfall and hosts many skiing grounds. In Nakanokawachi, the northernmost village of Shiga, snow reached a depth of 5.6 metres (18 ft) in 1936.[8]

As of 1 April 2014, 37% of the total land area of the prefecture was designated as Natural Parks (the highest total of any prefecture), namely the Biwako and Suzuka Quasi-National Parks; and Kotō, Kutsuki-Katsuragawa, and Mikami-Tanakami-Shigaraki Prefectural Natural Parks.[9]

Municipalities

[edit]Cities

[edit]

City Town

Thirteen cities are located in Shiga Prefecture:

| Name | Area (km2) | Population | Population density (per km2) | Map | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rōmaji | Kanji | ||||

| 東近江市 | 388.58 | 113,460 | 291.99 |

| |

| 彦根市 | 196.84 | 113,349 | 575.84 |

| |

| 甲賀市 | 481.62 | 89,202 | 185.21 |

| |

| 湖南市 | 70.4 | 54,240 | 770.46 |

| |

| 草津市 | 67.82 | 141,945 | 2092.97 |

| |

| 米原市 | 250.46 | 38,473 | 153.61 |

| |

| 守山市 | 55.73 | 80,768 | 1449.27 |

| |

| 長浜市 | 680.79 | 119,043 | 174.86 |

| |

| 近江八幡市 | 177.45 | 82,116 | 462.76 |

| |

| 大津市 | 464.51 | 341,187 | 734.51 |

| |

| 栗東市 | 52.75 | 67,149 | 1272.97 |

| |

| 高島市 | 693 | 49,168 | 70.95 |

| |

| 野洲市 | 80.15 | 50,233 | 626.74 |

| |

Towns

[edit]These are the towns in each district:

| Name | Area (km2) | Population | Population density (per km2) | District | Map | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rōmaji | Kanji | |||||

| 愛荘町 | 37.98 | 20,730 | 545.81 | Echi District |

| |

| 日野町 | 117.63 | 21,677 | 184.28 | Gamō District |

| |

| 甲良町 | 13.66 | 6,932 | 507.47 | Inukami District |

| |

| 竜王町 | 44.52 | 12,130 | 272.46 | Gamō District |

| |

| 多賀町 | 135.93 | 7,382 | 54.31 | Inukami District |

| |

| 豊郷町 | 7.78 | 7,588 | 975.32 | Inukami District |

| |

Mergers

[edit]Politics

[edit]

Taizō Mikazuki, a former member of the House of Representatives from Shiga, was narrowly elected governor in July 2014 with center-left support against ex-METI-bureaucrat Takashi Koyari (supported by the center-right national-level ruling parties) to succeed governor Yukiko Kada. In June 2018, he was overwhelmingly reelected to a second term against one challenger, a communist.[10][11][12]

The prefectural assembly has 44 members from 16 electoral districts, and is elected in unified local elections. As of July 2019, the assembly was composed by caucus as follows: LDP 20 members, Team Shiga (CDP, DPP, former Kada supporters etc.) 14, JCP 4, Sazanami Club (of independents) 3, Kōmeitō 2, "independent"/non-attached 1.[13]

In the National Diet, Shiga is represented by four directly elected members of the House of Representatives and two (one per ordinary election) of the House of Councillors. For the proportional representation segment of the lower house, the prefecture forms part of the Kinki block. After the national elections of 2016, 2017 and 2019, the directly elected delegation to the Diet from Shiga consists of (as of August 1, 2019):

- in the House of Representatives

- for the 1st district in the west: Toshitaka Ōoka, LDP, 3rd term,

- for the 2nd district in the northeast: Ken'ichirō Ueno, LDP, 4th term,

- for the 3rd district on the southern shores of Lake Biwa: Nobuhide Takemura, LDP, 3rd term,

- for the 4th district in the southeast: Hiroo Kotera, LDP, 1st term,

- in the House of Councillors (Shiga At-large district)

- in the class of 2016 (term ends 2022): Takashi Koyari, LDP, 1st term,

- in the class of 2019 (term ends 2025): Yukiko Kada, independent sitting with the Hekisuikai caucus, 1st term.

Economy

[edit]

According to the Cabinet Office's statistics in 2014, the manufacturing sector accounted for 35.4% of Shiga's economic production, the highest proportion in Japan.[14]

Demographics

[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 651,050 | — |

| 1930 | 691,631 | +6.2% |

| 1940 | 703,679 | +1.7% |

| 1950 | 861,180 | +22.4% |

| 1960 | 842,695 | −2.1% |

| 1970 | 889,768 | +5.6% |

| 1980 | 1,079,898 | +21.4% |

| 1990 | 1,222,411 | +13.2% |

| 2000 | 1,342,832 | +9.9% |

| 2010 | 1,410,777 | +5.1% |

| 2015 | 1,412,916 | +0.2% |

| Source: [1] | ||

The population is concentrated along the southern shore of Lake Biwa in Otsu city (adjacent to Kyoto) and along the lake's eastern shore in cities such as Kusatsu and Moriyama, which are within commuting distance to Kyoto. The lake's western and northern shores are more rural and resort-oriented with white sand beaches. In recent years, many Brazilians settled in Shiga to work in nearby factories. 25,040 foreigners live in Shiga and 30% of foreigners were Brazilians as of December 2016.[16]

Culture

[edit]

Biwa Town (a part of Nagahama) is a home of The Tonda Traditional Bunraku Puppet Troupe.[citation needed]

Museums include the Sagawa Art Museum in Moriyama, the Lake Biwa Museum in Kusatsu and the Miho Museum in Kōka. In Kōka, a ninja house is preserved as a visitor center.[17]

Education

[edit]

Ten universities, two junior colleges, and a learning center of The Open University of Japan operate in Shiga.[18]

- Biwako-Gakuin University (Higashiomi)

- Biwako Seikei Sport College (Otsu)

- Nagahama Institute of Bio-Science and Technology (Nagahama)

- Ritsumeikan University (Kyoto and Kusatsu)

- Ryukoku University (Kyoto and Otsu)

- Seian University of Art and Design (Otsu)

- Seisen University (Hikone)

- Shiga Bunkyo Junior College (Nagahama)

- Shiga Junior College (Otsu)

- Shiga University (Hikone and Ōtsu)

- Shiga University of Medical Science (Otsu)

- University of Shiga Prefecture (Hikone)

An example of the educational content that is unique to Shiga Prefecture is Biwako Floating School, also known as Uminoko.[19] Biwako Floating School is the project for running an educational cruise program in which fifth grade pupils of elementary schools living in Shiga board a ship Uminoko on Lake Biwa and learn about the environment and ecosystem of the lake.[19]

Sports

[edit]The following sports teams are based in Shiga.

- Basketball: Shiga LakeStars

- Football (soccer): Lagend Shiga (Moriyama), MIO Biwako Kusastsu (later Reilac Shiga) (Kusatsu), Sagawa Shiga F.C. (Moriyama).

- Tennis: SHRIGGA AKA UVEAL

- Volleyball: Toray Arrows (women's volleyball team) (Otsu)

Transport

[edit]There are no airports within the prefecture itself. However, airports such as Chubu Centrair International Airport, Itami Airport, and Kansai International Airport are also used by air travellers from the prefecture.

Tourism

[edit]

In 2000 sixty-five thousand tourists visited Shiga.[20]

Festivals include the hikiyama matsuri (曳山祭; floats parade) festival, held in ten areas including Nagahama each April, one of the three major hikiyama festivals in Japan, which was designated an Important Intangible Cultural Property in 1979. During the festival ornate floats are mounted with miniature stages on which boys (playing both male and female roles) act in kabuki plays.[21]

Notable people

[edit]- Gentaro Kawase, president of Nippon Life Insurance.

- Hizaki, musician and songwriter.

- Kakuzo Kawamoto, business executive and politician.

- Kizo Yasui, business executive.

- Sōsuke Uno, the 75th Prime Minister of Japan.

- Takanori Nishikawa, singer and actor.

Sister states/provinces

[edit]Shiga has cooperative agreements with three states or provinces in other countries.[22]

Hunan, China

Hunan, China Michigan, United States, since 1968

Michigan, United States, since 1968 Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Notes

[edit]- ^ "2020年度国民経済計算(2015年基準・2008SNA) : 経済社会総合研究所 - 内閣府". 内閣府ホームページ (in Japanese). Retrieved 2023-05-18.

- ^ NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute, ed. (24 May 2016). NHK日本語発音アクセント新辞典 (in Japanese). NHK Publishing.

- ^ Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Shiga-ken" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 853, p. 853, at Google Books; "Kansai" at Japan Encyclopedia, p. 477, p. 477, at Google Books.

- ^ Nussbaum, "Ōtsu" at Japan Encyclopedia, p. 765, p. 765, at Google Books.

- ^ Nussbaum, "Provinces and prefectures" at Japan Encyclopedia, p. 780, p. 780, at Google Books.

- ^ "Shiga Prefecture mulls name change to draw more visitors". The Japan Times.

- ^ Shiga Prefecture. 余呉湖・天女の衣掛柳 [Lake Yogo - a willow hung a celestial robe] (in Japanese). Retrieved 2011-05-13.

- ^ Encyclopedia Shiga. p436.

- ^ "General overview of area figures for Natural Parks by prefecture" (PDF). Ministry of the Environment. 1 April 2014. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ Shiga prefectural government: Governor's office (Japanese, English machine translation available by clicking "Foreign Language")

- ^ The Japan Times, July 14, 2014: LDP candidate flounders in Shiga governor race, retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ NHK Senkyo Web, June 24, 2018: 2018滋賀県知事選, retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ Prefectural assembly: Members by caucus (in Japanese), retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ Shiga Prefecture. 滋賀県の紹介(滋賀県なんでも一番) [Introduction of Shiga prefecture; Best scores of Shiga] (in Japanese). Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ^ "The Japanese Mortality Database: Shiga". National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. 30 March 2025.

- ^ Shiga Prefecture. 滋賀県内の外国人人口 [The number of foreigners in Shiga Prefecture] (in Japanese). Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- ^ Biwako Visitors Bureau. "Experiencing Ninjutsu (Ninja's techniques) at the ninja's native place – Koka Ninjutsu Yashiki". Retrieved 2011-05-13.

- ^ Shiga Prefecture. 滋賀県内の大学・短期大学 [Universities and junior colleges in Shiga prefecture] (in Japanese). Retrieved 2011-05-08.

- ^ a b 吉川 宏, 就航25周年を迎えた学習船「うみのこ」での体験学習(第2章 海洋教育活動の事例紹介,<特集>日本の海洋教育活動), 日本船舶海洋工学会誌 KANRIN(咸臨), 2008, 21 巻, p. 27-, 公開日 2018/03/30, Online ISSN 2424-161X, Print ISSN 1880-3725, https://doi.org/10.14856/kanrin.21.0_27, https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/kanrin/21/0/21_KJ00005082122/_article/-char/ja

- ^ Shiga Prefecture. 湖国観光交流ビジョン 第2章 滋賀県観光の現状と課題 [The vision for tourism and exchange of the Lake Country. Chapter 2: present situation and problem about the Shiga tourism] (in Japanese). Retrieved 2011-05-13.

- ^ Biwako Visitors Bureau. 滋賀県観光情報:長浜曳山まつり [Shiga tourism information: Nagahama hikiyama festival] (in Japanese). Retrieved 2011-05-20.

- ^ Shiga Prefecture. 滋賀県の紹介(滋賀県の国際交流 姉妹・友好都市) [Introduction of Shiga prefecture; International exchanges of Shiga, friendship sister cities] (in Japanese). Retrieved 2010-11-25.

References

[edit]- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 58053128

- Shiga-ken hyakka jiten [Encyclopedia Shiga] (滋賀県百科事典, 1984). Tokyo: Yamato Shobo.

External links

[edit] Shiga travel guide from Wikivoyage

Shiga travel guide from Wikivoyage- Shiga Prefecture official page

- go.biwako - Travel Guide of Shiga Prefecture, Japan (Biwako Visitors Bureau)

- Shiga Prefecture Guide - GoJapanGo

- Shiga-ken.com

Shiga Prefecture

View on GrokipediaHistory

Prehistoric and Ancient Periods

The area of present-day Shiga Prefecture, dominated by Lake Biwa, preserves evidence of Jōmon period (c. 14,000–300 BCE) human activity through shell middens and submerged settlements, reflecting early reliance on the lake's aquatic resources for sustenance.[7] More than 90 underwater or lakeside archaeological sites have been documented around Lake Biwa, including Early Jōmon locations with carbonized materials indicating differential preservation challenges in lacustrine environments.[7][8] These findings, such as those at Aidani Kumahara near the lake, highlight cord-marked pottery and resource exploitation predating agricultural shifts.[9] Transitioning to the Yayoi period (c. 300 BCE–300 CE), settlements near Lake Biwa incorporated wet-rice cultivation, marking a shift from foraging to organized farming supported by the lake's fertile environs and water management.[10] Sites in the region, including those with stone tools and village structures like the fortified Otsu settlement, demonstrate agricultural innovation alongside continued fishing.[11] Lake Biwa functioned as a central resource hub, enabling fishing practices and serving as a conduit for trade and goods transport in ancient central Japan.[12] By the 7th century CE, the territory aligned with the Yamato state's consolidation, incorporating the Ōmi region (encompassing Shiga) into the imperial administrative framework of the Kinai core as Yamato authority extended control over key provinces.[13] The establishment of Enryaku-ji Temple in 788 CE on Mount Hiei by the monk Saichō, at Emperor Kanmu's behest to protect the nascent Heian capital, introduced Tendai Buddhism and elevated the area's religious and political significance within the early imperial order.[14] This monastic complex, spanning multiple precincts, drew imperial patronage and shaped regional influence through doctrinal training and esoteric practices.[15]Feudal and Edo Eras

During the late Heian and Kamakura periods, Ōmi Province (modern Shiga Prefecture) served as a strategic corridor to Kyoto, positioning it amid medieval clan conflicts such as the Genpei War (1180–1185), where its terrain facilitated military maneuvers between the Minamoto and Taira clans.[16] In the Sengoku period, Ōmi became a frequent battleground, exemplified by the Battle of Shizugatake in 1583, where Toyotomi Hideyoshi decisively defeated Shibata Katsuie, consolidating his power through control of key routes and castles in the province.[17] The nearby Battle of Sekigahara on October 21, 1600, further underscored Ōmi's geopolitical significance; Tokugawa Ieyasu's victory there stabilized the region by reallocating domains to loyalists, ending widespread instability and enabling centralized feudal governance.[18][19] Under the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1868), Ōmi's castle towns, such as Hikone, emerged as administrative centers under daimyo oversight. The Ii clan governed the Hikone Domain from Hikone Castle, originally constructed in the early 17th century after their relocation from Sawayama Castle, enforcing local order and fulfilling obligations to the shogun through assessed rice yields.[20][21] The domain's economy relied on rice production quotas, rated at approximately 300,000 koku—equivalent to the annual rice sustenance for 300,000 adult males—drawn from fertile plains irrigated by Lake Biwa, which underpinned feudal levies and samurai stipends.[20] Other domains, like Zeze and Ōmi-Hachiman, similarly managed taxation and defense, integrating Ōmi into the bakufu's network of han systems.[21] Parallel to daimyo rule, Ōmi's merchant clans, known as Ōmi-shōnin, rose economically during the Edo period by leveraging trade routes like the Nakasendō, which traversed the province en route from Edo to Kyoto.[22] These traders, originating from areas like Ōmi-Hachiman, specialized in commodities such as tatami mats, mosquito nets, hemp cloth, pottery, medicines, sake, and soy sauce, establishing early outposts in Edo and fostering nationwide distribution networks through principles of diligence, fairness, and innovation.[23][24][25] Their proto-commercial activities, often independent of samurai oversight, generated substantial wealth, with families expanding into rural industries and long-distance peddling, contributing to Ōmi's reputation for shrewd entrepreneurship amid the bakufu's regulated economy.[26][27]Modern Industrialization and Postwar Development

Following the Meiji Restoration, Shiga Prefecture was formally established on September 18, 1871, through the consolidation of territories from the former Hikone Domain and surrounding areas under the national abolition of feudal domains and creation of prefectures.[21] This administrative shift facilitated initial modernization efforts, including infrastructure improvements like the Lake Biwa Canal, completed in 1890, which diverted water to power nascent industries in nearby Kyoto and Osaka while supporting local agriculture and early manufacturing.[28] In the 1880s to 1920s, Shiga experienced modest industrialization centered on textiles, leveraging Omi region's merchant traditions and proximity to urban markets; factories such as those producing cotton and silk goods emerged in areas like Hikone and Otsu, though output remained secondary to national hubs like Osaka.[29] During World War II, Shiga sustained minimal direct damage from bombing campaigns, unlike major cities, due to its inland location and lack of heavy strategic targets, though wartime resource shortages strained local agriculture and evoked children from Osaka in 1944.[21] Postwar recovery accelerated in the 1950s-1970s amid Japan's high-growth era, with Shiga transitioning from agrarian dominance to commuter-based suburbs; Lake Biwa's water—supplying up to 40% of Kansai region's needs by the 1970s—fueled industrial expansion in Osaka and Kyoto, indirectly boosting Shiga's economy through population influx and infrastructure like expanded rail links, raising prefectural GDP growth to match national rates of 10% annually in the 1960s.[30] [28] Administrative reforms in the late 1990s and early 2000s addressed fiscal pressures from depopulation and national consolidation policies, merging 19 municipalities into 13 by 2006 to enhance efficiency; key amalgamations included the 2004 formation of Higashiōmi City from five eastern towns and the 2005 creation of Kōka City, reducing administrative costs by centralizing services amid Japan's broader Heisei mergers that halved nationwide municipalities from 3,229 in 1999.[21] [31]Geography and Environment

Topography and Hydrography

Shiga Prefecture covers an area of 4,017 km² and is entirely landlocked, lacking any coastline along the Sea of Japan or Pacific Ocean.[1] The prefecture's topography is dominated by the Ōmi Basin, a tectonic depression centered on Lake Biwa, which occupies roughly one-sixth of the total land area.[32] Surrounding the basin are mountain ranges including the Ibuki Mountains to the northeast, rising to 1,377 m at Mount Ibuki, the prefecture's highest peak; the Suzuka Mountains to the east, with elevations of 1,200–1,300 m; and the Hira Mountains to the west, alongside Mount Hiei at 848 m on the border with Kyoto Prefecture.[33][34][32] These uplands, comprising forested hills and peaks up to 1,000 m or more, encircle the low-lying basin and contribute to the prefecture's inland hydrological dynamics.[35] Lake Biwa, with a surface area of 670 km², forms the core of Shiga's hydrography as Japan's largest freshwater lake, holding a volume of 27.5 km³.[36] The lake is divided into a deeper northern basin (mean depth 46 m) and shallower southern basin (mean depth 3 m), fed by approximately 118 rivers originating from the encircling mountains, with the Adogawa River providing the largest inflow.[36][37] Its single outlet, the Seta River, drains southward toward Osaka Bay, underscoring the lake's role in channeling precipitation and runoff essential for regional water supply and agriculture without direct marine influence.[36] Geologically, Lake Biwa originated as a tectonic lake approximately 4 million years ago through fault-induced subsidence in the region's active tectonic setting, part of the broader Japanese archipelago's compressional forces.[38][39] This formation process, involving Mesozoic-Paleozoic bedrock and ongoing fault activity, exposes the area to seismic risks, as evidenced by historical observations and the prefecture's position near active faults like that west of the lake.[39][40] The basin's sediment accumulation from riverine inputs continues to shape its bathymetry, maintaining its status as a long-lived inland water body amid Japan's seismically dynamic environment.[41]Climate and Natural Hazards

Shiga Prefecture features a humid subtropical climate under the Köppen classification Cfa, marked by hot, humid summers and cool winters with moderate snowfall in higher elevations.[42] The annual average temperature hovers around 15 °C, with Lake Biwa exerting a moderating influence that dampens seasonal temperature extremes through its large thermal capacity, resulting in milder variations compared to inland areas farther from the lake.[43] Precipitation totals approximately 1,500 mm annually in the southern lowlands, escalating to 2,000–2,500 mm in the northern mountainous zones due to orographic effects from prevailing winds.[44] Rainfall concentrates in the June–July rainy season (tsuyu) and peaks further during the August–October typhoon period, when tropical cyclones from the Pacific introduce intense, short-duration downpours. Flooding constitutes the primary natural hazard, exacerbated by heavy typhoon-driven rains overwhelming river capacities and Lake Biwa's drainage systems. Empirical records indicate 20 major flood events between 1901 and 1950, rising to 92 from 1951 to 2000, correlating with observed increases in extreme precipitation intensity rather than overall volume changes.[45] These incidents typically inundate low-lying riparian and lakeside areas, with causal factors including saturated soils from prior rains and insufficient outflow channels, as seen in recurrent overflows of rivers like the Yasu and Ane. Typhoon passages, averaging 3–5 per season affecting the region, amplify risks through storm surges and wind-induced wave action on the lake, though structural interventions have mitigated peak damages since the mid-20th century. Seismic risks stem from proximal active faults, notably the Yanagase Fault in northeastern Shiga and the Western Lake Biwa Fault along the lake's western margin, capable of generating magnitude 6–7 quakes based on paleoseismic trenching data.[46] Historical seismicity remains low but recurrent, with no subduction-zone proximity reducing tsunami threats, yet inland ruptures pose liquefaction hazards in sedimentary basins around Otsu and Hikone. Annual preparedness drills, informed by national seismic catalogs, simulate fault-specific scenarios to address empirical vulnerabilities like ground shaking amplification near the lakebed.[46]Lake Biwa Ecosystem

Lake Biwa originated approximately 4 million years ago as a tectonic lake, making it the oldest freshwater body in Japan and a key site for studying long-term aquatic evolution.[47] Its morphology features a deep northern basin with an average depth of 44 meters and maximum of 104 meters, contrasted by a shallower southern basin averaging 3.5 meters and reaching 8 meters, which together hold a water volume of 27.5 cubic kilometers.[36] [48] This hydrological structure supports a residence time of about 5.5 years, with outflow via the Yodo River providing drinking water to roughly 14 million people downstream.[48] [49] The lake's isolation has fostered high endemism, with 62 species reported exclusively from its waters, including mollusks, crustaceans, and fish that diverged millions of years ago.[36] [50] Among the endemic fauna, the Biwa trout (Oncorhynchus biwaensis), a landlocked salmonid, exemplifies adaptive evolution in the lake's profundal zones, with phylogenetic divergence from relatives estimated between 1.3 and 13 million years ago.[51] [50] This biodiversity historically underpinned commercial fisheries, yielding around 5,000 tons of fish annually prior to the 1980s, dominated by native cyprinids and salmonids adapted to the lake's oligomictic stratification.[52] The ecosystem's productivity stems from nutrient inputs via over 450 inflowing rivers, sustaining a food web where endemic species occupy niches shaped by the lake's bathymetric gradients.[53] Introductions of invasive species, such as the bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus) in the 1960s, have disrupted this balance, with empirical data showing substantial declines in native cyprinid populations due to predation and competition.[54] [55] Bluegill proliferation particularly decimated local crucian carp stocks, reducing abundances by up to 50% in affected shallow areas, as evidenced by long-term monitoring of fishery catches and community shifts.[54] These invasions highlight the vulnerability of ancient lake endemics to anthropogenic translocations, altering trophic dynamics without corresponding recovery in native yields.[55]Environmental Policies and Challenges

In the 1970s, Lake Biwa suffered from eutrophication driven by phosphate inflows from household detergents and agricultural runoff, resulting in algal blooms, red tides, and degraded water quality that threatened its role as a primary water source. Shiga Prefecture responded with the 1979 Eutrophication Prevention Ordinance, which banned the sale, distribution, and gifting of phosphorus-containing synthetic detergents starting in 1980, a measure spurred by citizen campaigns and enforced through local monitoring. This policy causally reduced phosphate loading from domestic sources, as evidenced by subsequent declines in nutrient-driven algal outbreaks.[56][57] Parallel investments in sewage infrastructure, initiated in 1973 and expanded through the 1980s, included advanced treatment plants capable of removing nitrogen and phosphorus, leading to substantial improvements in biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and overall water clarity by the early 2000s. These interventions, funded by prefectural bonds and national support, prevented the lake's total collapse and restored usability for drinking and fisheries, underscoring the effectiveness of direct pollution controls over broader regulatory frameworks. However, the high capital costs—exceeding billions of yen—and ongoing maintenance burdens highlight the economic trade-offs of such infrastructure-heavy approaches.[58][59] To combat invasive species threats, Shiga Prefecture enacted a 2002 ordinance prohibiting the release of exotic fish like bluegill and largemouth bass, which had proliferated since the 1960s and devastated native populations through predation and competition. While enforcement includes fines and public education, empirical data reveal persistent biodiversity erosion, with cyprinid fish catch per unit effort declining steadily from 1966 to 2022 due to these invasives and habitat alterations. Local fishing economies have suffered, with total catches dropping to a fraction of historical levels, prompting critiques that release bans alone fail to eradicate established populations or offset regulatory restrictions on harvest methods that further constrain livelihoods.[60][55] Overgrowth of submerged aquatic macrophytes, emerging prominently since 1995 amid clearer waters from prior nutrient reductions, has introduced new challenges including foul odors from decaying plants and obstructed navigation for boats in the south basin. Prefecture-led removal and composting programs address these issues but incur significant labor and disposal costs, while the proliferation—ironically linked to oligotrophication success—exacerbates ecosystem imbalances without fully restoring endemic species diversity. These dynamics illustrate how initial policy triumphs can spawn secondary problems, with overregulation potentially amplifying economic pressures on riparian communities dependent on the lake's resources.[61][62]Administrative Divisions

Cities and Urban Centers

Shiga Prefecture encompasses 13 cities that constitute its core urban framework, concentrating administrative, manufacturing, and commuter functions while driving the prefecture's economic output, particularly in electronics and machinery sectors. These urban centers house roughly 85% of the prefecture's 1.4 million residents as of early 2025, with select cities like Kusatsu and Moriyama registering slight population gains of under 0.5% annually from 2020 to 2024, amid broader stagnation and rural outflows linked to aging demographics and out-migration to Kyoto or Osaka.[63] [64] Ōtsu, the capital with approximately 340,000 residents, operates as the prefectural administrative core, hosting government institutions, judicial bodies, and educational facilities, supplemented by lakeside commerce and proximity to Kyoto via rail. Kusatsu, at around 140,000 people, functions as a manufacturing and logistics node with plants producing air conditioners and components, while serving as a primary commuter base for Kyoto's workforce through dense rail and highway access.[65] [66] Hikone, population nearing 111,000, emphasizes cultural preservation around its intact Edo-period castle—a designated national treasure—bolstering tourism alongside light industrial activities in plastics and machinery.[67] Nagahama (about 118,000 residents) and Ōmihachiman (roughly 81,000) retain legacies as Lake Biwa trading ports, now channeling economic roles into heritage-driven tourism via canal networks, merchant warehouses, and annual festivals that draw regional visitors. Manufacturing-oriented cities including Rittō, Yasu, and Moriyama support electronics assembly and automotive parts production, with Yasu hosting R&D-intensive facilities for capacitors and precision components from companies like Murata Manufacturing and Kyocera.[68] [69] Smaller urban hubs such as Maibara, Konan, Kōka, Takashima, Higashiōmi, and Yasu further integrate logistics and agriculture processing, leveraging expressway interchanges for distribution. Without seaports, Shiga's cities rely on inland connectivity via the Meishin Expressway and Tōkaidō rail lines, positioning the prefecture as a critical overland junction between Kansai industrial belts and Chūbu manufacturing zones, facilitating efficient freight and passenger flows.[5] This infrastructure underpins urban economic resilience, with manufacturing output comprising over 44% of prefectural GDP as of 2020 data.[70]Towns and Rural Areas

Shiga Prefecture comprises three towns—Aishō, Kōnan, and Taga—as its primary rural municipalities, with no villages extant following mergers in the early 21st century.[64] These towns, totaling around 49,000 residents as of recent estimates, represent less than 4% of the prefecture's 1.4 million population but sustain significant agricultural activity on lakefront and hilly terrains.[64] Aishō, located in eastern Shiga, focuses on paddy rice cultivation, leveraging fertile plains for high-yield wet-rice farming that historically positioned the prefecture as a key rice supplier in the Kinki region.[71] Kōnan and Taga, situated in the southern and eastern peripheries, emphasize horticulture and tea production alongside rice, with terraced fields adapting to undulating landscapes.[72] Agricultural persistence defines these areas, where rice remains the staple crop, supplemented by specialty fruits such as strawberries in lake-adjacent zones like those near Makino in broader rural Shiga.[71] [73] Small-scale manufacturing, including food processing for local produce, complements farming, though economies remain agrarian with limited diversification.[72] However, depopulation pressures are acute, driven by an aging demographic where over 60% of farmers exceed 65 years old, mirroring national trends but intensified in peripheral towns with outmigration to urban centers like Ōtsu and Kusatsu.[74] Abandoned farmland has risen amid these shifts, with projections estimating 10% of Shiga's cultivable land may lack operators within a decade due to successor shortages and rural exodus.[74] In towns like Taga, low population density—around 100 persons per square kilometer—exacerbates land underutilization, prompting local initiatives for community farming to consolidate plots and mitigate biodiversity loss from overgrown fields.[64] [75] Despite these challenges, rural Shiga retains self-sufficiency in rice and contributes to prefectural goals of environmentally committed agriculture, protecting Lake Biwa's watershed through reduced chemical inputs.[71]| Town | Population (approx. 2020) | Primary Agricultural Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Aishō | 17,600 | Rice paddy cultivation[71] |

| Kōnan | 25,500 | Rice, tea, horticulture[72] |

| Taga | 6,100 | Terraced rice, community-managed fields[75] [64] |