Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

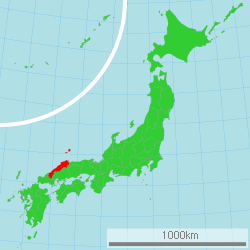

Shimane Prefecture

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Shimane Prefecture (島根県, Shimane-ken; Japanese pronunciation: [ɕiꜜ.ma.ne, ɕi.ma.neꜜ.keɴ][2]) is a prefecture of Japan located in the Chūgoku region of Honshu.[3] Shimane Prefecture is the second-least populous prefecture of Japan at 665,205 (February 1, 2021) and has a geographic area of 6,708.26 km2. Shimane Prefecture borders Yamaguchi Prefecture to the southwest, Hiroshima Prefecture to the south, and Tottori Prefecture to the east.

Matsue is the capital and largest city of Shimane Prefecture, with other major cities including Izumo, Hamada, and Masuda.[4] Shimane Prefecture contains the majority of the Lake Shinji-Nakaumi metropolitan area centered on Matsue, and with a population of approximately 600,000 is Japan's third-largest metropolitan area on the Sea of Japan coast after Niigata and Greater Kanazawa. Shimane Prefecture is bounded by the Sea of Japan coastline on the north, where two-thirds of the population live, and the Chūgoku Mountains on the south. Shimane Prefecture governs the Oki Islands in the Sea of Japan which juridically includes the disputed Liancourt Rocks (竹島, Takeshima). Shimane Prefecture is home to Izumo-taisha, one of the oldest Shinto shrines in Japan, and the Tokugawa-era Matsue Castle.

History

[edit]

Early history

[edit]The history of Shimane starts with Japanese mythology. The Shinto god Ōkuninushi was believed to live in Izumo, an old province in Shimane. Izumo Shrine, which is in the city of Izumo, honors the god.[5] At that time, the current Shimane prefecture was divided into three parts: Iwami, Izumo, and Oki.[6] That lasted until the abolition of the han system took place in 1871. During the Nara period, Kakinomoto no Hitomaro wrote a poem on Shimane's nature when he was sent as the Royal governor.[7]

Later on in the Kamakura period (1185–1333), the Kamakura shogunate forced emperors Go-Toba and Godaigo into exile in Oki. Emperor Go-Daigo later escaped from Oki and began rallying supporters against the shogunate, which proved successful.[8]

Middle Ages

[edit]

During the Muromachi period (1336–1573), Izumo and Oki were controlled by the Kyōgoku clan. However, after the Ōnin War, the Amago clan expanded power based in Gassantoda Castle and the Masuda clan dominated Iwami Province. The Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine was located between Amago territory and Masuda territory, and there were many battles between the clans for the silver. In 1566 Mōri Motonari conquered Izumo, Iwami, and Oki.[8] In 1600, after over 30 years of Mori control, Horio Yoshiharu entered Izumo and Oki as the result of Battle of Sekigahara, which Mori lost. Following the change, Horio Yoshiharu decided to move to build Matsue Castle instead of Gassan-Toda, and soon after Yoshiharu's death the castle was completed. In 1638, the grandson of Tokugawa Ieyasu Matsudaira Naomasa became the ruler because the Horio clan had no heir, and his family ruled until the abolition of the han system.

The Iwami area was split into three regions: the mining district, under the direct control of the Shogunate, the Hamada clan region, and the Tsuwano clan region. The Iwami Ginzan, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, produced silver and was one of the nation's largest silver mines by the early 17th century. The Hamada clan was on the shogunate's side in the Meiji Restoration, and the castle was burned down. The Tsuwano clan, despite then being ruled by the Matsudaira, was on the emperor's side in the restoration.[9]

Modern age

[edit]In 1871, the abolition of the han system placed the old Shimane and Hamada Provinces in the current area of Shimane Prefecture. Later that year, Oki became part of Tottori. In 1876, Hamada Prefecture was merged into Shimane Prefecture. Also, Tottori Prefecture was added in the same year. However, five years later, in 1881, the current portion of Tottori Prefecture was separated and the current border was formed.[9]

Geography

[edit]Shimane Prefecture is situated on the Sea of Japan side of the Chūgoku region. Because of its mountainous landscape, rice farming is done mostly in the Izumo plain where the city of Izumo is located.[10] Another major landform is the Shimane peninsula. The peninsula is located across the Sea of Japan from Izumo to Sakaiminato, which is located in Tottori prefecture. Also, the peninsula created two brackish lakes, Lake Shinji and Nakaumi. The island of Daikon is located in Nakaumi. Off the main island of Honshū, the island of Oki belongs to Shimane prefecture as well. The island itself is in the Daisen-Oki National Park.[10] Shimane also claims the use of Liancourt Rocks, over which they are in dispute with South Korea.[11]

As of 1 April 2012, 6% of the total land area of the prefecture was designated as Natural Parks, namely Daisen-Oki National Park; Hiba-Dōgo-Taishaku and Nishi-Chūgoku Sanchi Quasi-National Parks; and eleven Prefectural Natural Parks.[12]

Most major cities are located either on the seaside, or along a river.[10]

Cities

[edit]

City Town Village

Eight cities are located in Shimane Prefecture, the largest in population being Matsue, the capital, and the smallest being Gōtsu. The cities Masuda, Unnan, Yasugi, and Gōtsu had a slight population increase due to the mergers in the early 2000s.[13]

| Name | Area (km2) | Population | Map | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rōmaji | Kanji | |||

| 江津市 | 268.51 | 24,009 | ||

| 浜田市 | 689.6 | 57,142 | ||

| 出雲市 | 624.36 | 172,039 | ||

| 益田市 | 733.16 | 46,892 | ||

| 松江市 | 572.99 | 202,008 | ||

| 大田市 | 436.11 | 34,354 | ||

| 雲南市 | 553.4 | 38,281 | ||

| 安来市 | 420.97 | 38,875 | ||

Towns and villages

[edit]These are the towns and villages of each district. The number of towns and villages greatly decreased during the mergers. However, they hold about one-third of the prefecture's population.[13]

| Name | Area (km2) | Population | District | Type | Map | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rōmaji | Kanji | |||||

| 海士町 | 33.5 | 2,293 | Oki District | Town | ||

| 知夫村 | 13.7 | 657 | Oki District | Village | ||

| 飯南町 | 242.84 | 4,908 | Iishi District | Town | ||

| 川本町 | 106.39 | 3,331 | Ōchi District | Town | ||

| 美郷町 | 282.92 | 4,712 | Ōchi District | Town | ||

| 西ノ島町 | 55.98 | 2,923 | Oki District | Town | ||

| 隠岐の島町 | 242.97 | 14,422 | Oki District | Town | ||

| 奥出雲町 | 368.06 | 12,655 | Nita District | Town | ||

| 邑南町 | 419.29 | 10,922 | Ōchi District | Town | ||

| 津和野町 | 307.09 | 7,478 | Kanoashi District | Town | ||

| 吉賀町 | 336.29 | 6,231 | Kanoashi District | Town | ||

Mergers

[edit]| April 1976 | January 2011 | January 2012 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Izumo Region | Matsue City (Old System) | Matsue City (New System) | Matsue City (August 1, 2011 Merger with Higashiizumo Town) | |

| Yatsuka District | Kashima Town | |||

| Shimane Town | ||||

| Mihonoseki Town | ||||

| Yakumo Village | ||||

| Tamayu Town | ||||

| Shinji Town | ||||

| Yatsuka Town | ||||

| Higashiizumo Town | ||||

| Yasugi City (Old System) | Yasugi City (New System) | Yasugi City | ||

| Nogi District | Hirose Town | |||

| Hakuta Town | ||||

| Nita District | Yokota Town | Okuizumo Town | ||

| Nita Town | ||||

| Izumo City (Old System) | Izumo City (New System) | Izumo City (October 1, 2011 Merger with Hikawa Town) | ||

| Hirata City | ||||

| Hikawa District | Taisha Town | |||

| Koryo Town | ||||

| Taki Town | ||||

| Sada Town | ||||

| Hikawa Town | ||||

| Ōhara District | Daitō Town | Unnan City | ||

| Kamo Town | ||||

| Kisuki Town | ||||

| Iishi District | Mitoya Town | |||

| Kakeya Town | ||||

| Yoshida Village | ||||

| Tonbara Town | Iinan Town | |||

| Akagi Town | ||||

| Iwami Region | Ōda City (Old System) | Ōda City (New System) | Ōda City | |

| Nima District | Yunotsu Town | |||

| Nima Town | ||||

| Gōtsu City (Old System) | Gōtsu City (New System) | Gōtsu City | ||

| Ōchi District | Sakurae Town | |||

| Ōchi Town | Misato Town | |||

| Daiwa Village | ||||

| Iwami Town | Ōnan Town | |||

| Mizuho Town | ||||

| Hasumi Village | ||||

| Kawamoto Town | ||||

| Hamada City (Old System) | Hamada City (New System) | Hamada City | ||

| Naka District | Asahi Town | |||

| Kanagi Town | ||||

| Misumi Town | ||||

| Yasaka Village | ||||

| Masuda City (Old System) | Masuda City (New System) | Masuda City | ||

| Mino District | Mito Town | |||

| Hikimi Town | ||||

| Kanoashi District | Tsuwano Town (Old System) | Tsuwano Town (New System) | Tsuwano Town | |

| Nichihara Town | ||||

| Muikaichi Town | Yoshika Town | |||

| Kakinoki Village | ||||

| Oki Region | Oki District | Saigō Town | Okinoshima Town | |

| Fuse Village | ||||

| Goka Village | ||||

| Tsuma Village | ||||

| Nishinoshima Town | ||||

| Ama Town | ||||

| Chibu Village | ||||

Climate

[edit]Shimane prefecture has a sub-tropical climate. Winter is cloudy with a little snow, and summer is humid. The average annual temperature is 14.6 °C (58.3 °F). It rains almost every day in the rainy season, from June to mid-July. The highest average monthly temperature occurs in August with 26.3 °C (79.3 °F). The average annual precipitation is 1,799 millimetres (70.8 in), higher than Tokyo's 1,467 mm (57.8 in) and Obihiro with 920 mm (36.2 in).[13]

| Average Year (Month) |

Oki | Izumo (Coastal) | Izumo (Inland) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Okinoshima Saigo |

Okinoshima Saigo Cape |

Ama | Matsue Kashima |

Matsue | Hikawa | Izumo | Okuizumo Yokota |

Unnan Kakeya |

Iinan Akana | ||

| Average Temperature (°C) |

Warmest Month | 25.6 (Aug) |

25.8 (Aug) |

25.6 (Aug) |

26.3 (Aug) |

25.8 (Aug) |

24.0 (Aug) |

24.5 (Aug) |

23.4 (Aug) | ||

| Coldest Month | 3.9 (Feb) |

4.5 (Feb) |

4.4 (Feb) |

4.2 (Jan) |

4.5 (Feb) |

0.7 (Feb) |

2.3 (Feb) |

0.4 (Jan, Feb) | |||

| Rainfall (mm) |

Heaviest Month | 211.6 (Sept) |

227.0 (July) |

218.0 (Sept) |

240.5 (July) |

236.2 (July) |

234.2 (July) |

257.1 (July) |

282.2 (July) | ||

| Driest Month | 110.4 (Oct) |

96.4 (Feb) |

104.7 (April) |

114.5 (April) |

96.3 (Feb) |

103.4 (April) |

120.7 (April) |

116.5 (Oct) | |||

| Average Year (Month) |

Iwami (Coastal) | Iwami (Inland) | |||||||||

| Ōda | Hamada | Masuda | Masuda City Takatsu |

Kawamoto | Ōnan |

Hamada City Yasaka |

Tsuwano | Yoshika | Yoshika Muikaichi | ||

| Average Temperature (°C) |

Warmest Month | 26.5 (Aug) |

26.2 (Aug) |

26.8 (Aug) |

24.2 (Aug) |

23.9 (Aug) |

23.6 (Aug) |

25.7 (Aug) |

24.5 (Aug) | ||

| Coldest Month | 4.9 (Jan, Feb) |

5.8 (Feb) |

5.4 (Jan, Feb) |

2.7 (Jan) |

0.8 (Jan) |

1.5 (Jan) |

3.0 (Jan) |

1.9 (Jan) | |||

| Rainfall (mm) |

Heaviest Month | 246.3 (July) |

257.7 (July) |

223.9 (June) |

260.2 (July) |

260.6 (July) |

340.0 (July) |

285.6 (July) |

337.4 (June) | ||

| Driest Month | 98.3 (Feb) |

90.9 (Feb) |

87.9 (Feb) |

112.5 (Feb) |

109.2 (Nov) |

130.4 (April) |

99.7 (Dec) |

76.8 (Dec) | |||

Transportation

[edit]Airports

[edit]Three airports serve Shimane. The Izumo Airport located in Izumo is the largest airport in the prefecture in terms of passengers and has regular flights to Haneda Airport, Osaka Airport, Fukuoka Airport, and Oki Airport. The Iwami Airport has two flights each day to Haneda and Osaka and 2 arrivals. Oki Airport has scheduled flights to Osaka and Izumo Airports.[14]

Rail

[edit]JR West and Ichibata Electric Railway serves the prefecture in terms of rail transportation. The Sanin Main Line goes through the prefecture on the Sea of Japan side into major cities such as Matsue and Izumo.[15] Izumoshi and Matsue stations are the major stops in the prefecture. The Kisuki line, which forks from Shinji Station on the Sanin Line, connects with the Geibi Line in Hiroshima Prefecture, cutting into the Chūgoku Mountains.[15] Ichibata Electric Railway serve the Shimane peninsula from Dentetsu-Izumoshi Station and Izumo Taisha-mae Station to Matsue Shinjiko-Onsen Station.[16]

JR West has three Limited Express trains to Shimane, which are Super Matsukaze, Super Oki, and Yakumo.[17] Additionally, the overnight limited express Sunrise Izumo operates daily between Tokyo and Izumoshi.

Roads

[edit]General roads

[edit]- Japan National Route 9

- Japan National Route 54

- Japan National Route 180

- Japan National Route 184

- Japan National Route 186

- Japan National Route 187

- Japan National Route 191

- Japan National Route 261

- Japan National Route 314

- Japan National Route 375

- Japan National Route 431

- Japan National Route 432

- Japan National Route 485

- Japan National Route 488

Highways

[edit]The four expressways in the prefecture connect major cities with other prefectures. The Matsue expressway connects Matsue with Unnan and Yonago in Tottori prefecture. Hamada Expressway forks from the Chūgoku Expressway at Kita-Hiroshima and stretches to Hamada.[10]

Ferries

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

Oki Saigo Port

Economy

[edit]In Shimane, the largest employer is the retail industry, employing over 60,000 workers. The supermarket, Mishimaya, and the hardware store, Juntendo, are examples of companies based in Shimane. The manufacturing industry has the second highest number of employees with 49,000 workers. [citation needed]

Companies based in Shimane

[edit]Manufacturing

[edit]Financial

[edit]Others

[edit]Major factories

[edit]Demographics

[edit]

One-third of the prefecture's population is concentrated in the Izumo-Matsue area. Otherwise, over two-thirds of the population is on the coastline. A reason for the population distribution is that the Chūgoku Mountains make the land inland harder to inhabit. The capital, Matsue, has the smallest population of all 47 prefectural capitals. Shimane has also the largest percentage of elderly people.[13] The province had an estimated 743 centenarians per million inhabitants in September 2010, the highest ratio in Japan, overtaking Okinawa Prefecture (667 centenarians per million).[18]

Population by age

[edit]Total Population in age groups

2007 Estimated Population

Unit: Thousands

Population in age groups by gender

2007 Estimated population

Unit: Thousands

- Source: Graph 10/Prefectures Age(In Age groups), Gender divided population-Total Population

(Ministry of Internal Affairs Statistics Bureau)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Comparison of Population Distribution between Shimane and Japanese National Average | Population Distribution by Age and Sex in Shimane | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

■ Shimane

■ Japan (average) |

■ Male

■ Female | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 Census, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications - Statistics Department | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 715,000 | — |

| 1930 | 740,000 | +3.5% |

| 1940 | 741,000 | +0.1% |

| 1950 | 913,000 | +23.2% |

| 1960 | 889,000 | −2.6% |

| 1970 | 773,575 | −13.0% |

| 1980 | 784,795 | +1.5% |

| 1990 | 781,021 | −0.5% |

| 2000 | 761,503 | −2.5% |

| 2010 | 717,397 | −5.8% |

| 2020 | 679,626 | −5.3% |

| [19][20] | ||

Culture

[edit]Cultural assets

[edit]

- World Cultural Heritage

- National Treasures

- Armour Laced with white thread (Hinomisaki Shrine)

- Bronze bells from the Kamo-Iwakura site Unearthed bronze bell-shaped vessel (Unnan City)

- Izumo-taisha Main Shrine (Izumo City)

- Kamosu Shrine Main Shrine (Matsue City)

- Kojindani Ruins Unearthed ruins (Izumo City)

- Toiletry case with autumn field and deer design (Izumo-taisha)

- Important Traditional Building Preservation Area

- Ōmori (Ōda City)

- Yunotsu (Ōda City)

Dialects

[edit]- Iwami dialect

- Unpaku dialect (Izumo dialect, Oki dialect, etc.)

Universities in Shimane Prefecture

[edit]- Shimane University, Matsue and Izumo (National university)[21]

- The University of Shimane, Hamada (Prefectural university)[22]

Tourism

[edit]- Adachi Museum of Art

- Aquas Aquarium

- Iwami Art Museum

- Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine

- Izumo-taisha

- Izumo Province

- Matsue Castle

- Mt. Sanbe

- Shimane Art Museum

- Shimane Vogel Park

- Shimane Winery

- Tamatsukuri Onsen

Prefectural symbols

[edit]The prefectural flower is the mountain peony. On the island of Daikonjima, they have been grown from at least the 18th century.[23]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "2020年度国民経済計算(2015年基準・2008SNA) : 経済社会総合研究所 - 内閣府". 内閣府ホームページ (in Japanese). Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ^ NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute, ed. (May 24, 2016). NHK日本語発音アクセント新辞典 (in Japanese). NHK Publishing.

- ^ Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Shimane Province" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 859, p. 859, at Google Books; "Chūgoku" at p. 127, p. 127, at Google Books

- ^ Nussbaum, "Matsue" at p. 617, p. 617, at Google Books

- ^ "Izumo Shrine website". Archived from the original on August 23, 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- ^ Nussbaum, "Provinces and prefectures" at p. 780, p. 780, at Google Books

- ^ Shimane Prefecture introduction Archived March 3, 1997, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b 古川清行 Furukawa Kiyoyuki (2003). スーパー日本史 Super Nihon-shi. 講談社 Kōdansha. ISBN 4-06-204594-X.

- ^ a b History of Shimane Prefecture Archived November 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d 新編 中学校社会科地図 Updated Social studies map for Junior High school. 帝国書院 Teikoku Shoin. 2007. ISBN 978-4-8071-4091-6.

- ^ Liancourt Rocks

- ^ "General overview of area figures for Natural Parks by prefecture" (PDF). Ministry of the Environment. April 1, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ a b c d 考える社会科地図 Kangaeru Shakaika Chizu. 四谷大塚出版 Yotsuya-Ōtsuka Shuppan. 2005. p. 113.

- ^ Flight schedule of Oki Airport Archived August 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Route map for JR West

- ^ Route map of Ichibata Electric Railway

- ^ JR West website on limited express trains

- ^ Japan Times “Centenarians to Hit Record 44,000”. The Japan Times, Sept. 15, 2010. Okinawa Prefecture also had the largest loss of young and middle-aged population during the Pacific War.

- ^ Shimane 1995-2020 population statistics

- ^ Shimane 1920-2000 population statistics

- ^ Shimane University

- ^ University of Shimane

- ^ Symbols of Shimane Prefecture: From Shimane Prefecture website Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

References

[edit]- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 58053128

External links

[edit]- Official homepage of Shimane Prefecture

- National Archives of Japan ... Shimane map (1891)[permanent dead link]

- Sightseeing In Shimane

Shimane Prefecture

View on GrokipediaGeography

Physical Geography

Shimane Prefecture occupies 6,707 square kilometers along the northern coast of western Honshu, forming a narrow, elongated territory stretching approximately 230 kilometers east to west.[6][7] Its northern boundary consists of a rugged coastline along the Sea of Japan, while the southern edge abuts the Chūgoku Mountain Range, which dominates the interior terrain.[6] The landscape features steep mountainous areas covering much of the prefecture, with flatter plains limited primarily to coastal strips and the Izumo Plain in the central-eastern region.[8] Volcanic activity has shaped notable landforms, including the stratovolcano Mount Sanbe in Ōda, which rises to 1,126 meters at its highest peak, Osanbe, and contains a central caldera.[9] Significant water bodies include Lake Shinji, a brackish lake formed by the mixing of freshwater and seawater, spanning approximately 80 square kilometers and ranking as Japan's seventh-largest lake by area.[10] Adjacent to Lake Shinji lies Nakaumi, another brackish lagoon connected via the Hiuchi River, together forming a vital coastal wetland system.[1] Major rivers such as the Hii River and Takiba River originate in the southern mountains and flow northward, emptying into Lake Shinji and supporting regional hydrology.[11] Offshore, Shimane encompasses the Oki Islands, a cluster of over 180 volcanic islets located 40 to 80 kilometers northwest in the Sea of Japan, with four main inhabited islands featuring diverse basalt formations and designated as a UNESCO Global Geopark for their geological significance.[12][13] The islands' terrain includes steep cliffs, calderas, and unique coastal erosions resulting from volcanic origins dating back millions of years. The prefecture's overall elevation varies from sea level along the coast to peaks exceeding 1,300 meters in the Chūgoku range, such as Mount Osorakan at 1,347 meters on the southern border.[14]Administrative Divisions

Shimane Prefecture is administratively subdivided into eight cities (shi), ten towns (chō or machi), and one village (mura), totaling 19 municipalities as of 2023.[15] This structure reflects ongoing municipal consolidations since the 2000s, aimed at improving administrative efficiency amid Japan's declining population. The prefectural capital is Matsue City, which serves as the primary economic and administrative hub.[16] The eight cities are:- Gōtsu (江津市)

- Hamada (浜田市)

- Izumo (出雲市)

- Masuda (益田市)

- Matsue (松江市)

- Ōda (大田市)

- Unnan (雲南市)

- Yasugi (安来市)

Climate and Natural Environment

Shimane Prefecture features a temperate climate with pronounced seasonal contrasts, shaped by its exposure to the Sea of Japan. In Matsue, the prefectural capital, the annual average temperature stands at 15.4 °C, accompanied by approximately 1,784 mm of precipitation. Winters are cold and snowy, with northwesterly winds carrying moisture from the continent leading to heavy snowfall accumulations, often necessitating snow tires for local travel. Summers are warm and humid, while rainfall peaks in September at around 220 mm.[18][19][20] The natural environment is diverse, encompassing volcanic mountains, brackish lakes, and rugged coastlines within Daisen-Oki National Park. Mount Daisen, the highest peak in the Chūgoku region at 1,729 meters, supports layered forests transitioning from Japanese red pine and oak-dominated secondary woodlands below 800 meters to alpine species at higher elevations.[21][22] Inland, Lake Shinji—a brackish lagoon spanning 79.25 km² with an average depth of 4.5 meters—forms a vital wetland ecosystem shared with adjacent Lake Nakaumi, designated under the Ramsar Convention. This area hosts approximately 200 bird species, including migratory and rare variants observable year-round.[23][24] Coastal zones exhibit dramatic geology, such as the 257-meter Maten-gai Cliffs sculpted by Japan Sea waves, while the Oki Islands, part of the national park and a UNESCO Global Geopark since 2013, showcase erosion-carved volcanic terrains and marine biodiversity. Terrestrial wildlife includes wild boars and forest-dependent species, though invasive non-natives pose ongoing challenges to native flora and fauna.[25][26][27]History

Prehistoric and Ancient Periods

The region encompassing modern Shimane Prefecture exhibits evidence of Paleolithic human activity, with stone tools unearthed at the Sunabara site in Izumo dated to approximately 120,000 years ago via stratigraphic analysis and comparative typology, indicative of Middle Paleolithic tool-making traditions adapted to local environments.[28] The Jōmon period (c. 14,000–300 BCE) saw semi-sedentary hunter-gatherer-fisher communities across the Japanese archipelago, including Shimane's coastal and inland areas, though major stratified sites are more prominent elsewhere; local evidence includes pottery sherds and pit dwellings consistent with broader Jōmon adaptations to foraging and seasonal mobility.[29] The Yayoi period (c. 300 BCE–250 CE) marked a shift to rice agriculture, metallurgy, and social complexity in the Izumo region, with excavations at the Okite site revealing a 5.3-meter-long dugout canoe carbon-dated to this era, demonstrating advanced fluvial navigation and resource exploitation capabilities. At Kojindani, archaeologists recovered a cache of over 350 bronze thrusting swords and 16 dōtaku bells between 1984 and 1985, alongside spears and halberds, signaling ritual deposition and the authority of local elites who controlled bronze production and trade networks linked to continental influences.[30][31] Transitioning into the Kofun period (c. 250–538 CE), Shimane's ancient societies constructed burial mounds reflecting stratified hierarchies, such as the Kamienyatsukiyama Kofun in Izumo—a large keyhole-shaped tumulus containing grave goods that attest to chieftain-level power and possible continental stylistic exchanges.[32] Square kofun variants, dating from late Yayoi into early Kofun, further highlight Izumo's distinct regional traditions amid the rise of the Yamato polity, with bronze swords and bells underscoring a continuity of martial and ceremonial prestige that positioned Izumo as a mythological and political counterpoint in early Japanese state formation.[33][34]Medieval and Feudal Eras

In the Kamakura period (1192–1333), Izumo Province fell under the oversight of military governors appointed by the shogunate, marking the shift toward feudal structures dominated by samurai clans amid weakening imperial authority.[35] Local power dynamics began favoring warrior families, though central control remained nominal due to the province's peripheral location.[36] The Muromachi period (1336–1573) saw the Kyogoku clan appointed as shugo (military governor) of Izumo, with deputies like the Amago clan—descended from Kyogoku lineage—managing day-to-day administration as shugodai.[37] The Amago, initially subordinates, leveraged internal shogunate weaknesses to assert autonomy, transitioning from deputy roles to independent daimyo by the late 15th century.[37] During the Sengoku period (1467–1603), an extension of feudal fragmentation, Amago Tsunehisa (1458–1541) consolidated control over Izumo by 1508, extending influence to Iwami Province and beyond through military campaigns, including the conquest of Oki Islands.[38] Gassan-Toda Castle, originally constructed in the 14th century by the Sasaki clan, became the Amago stronghold, symbolizing their regional dominance.[39] The 1526 discovery of silver deposits at Iwami Ginzan revolutionized the local economy, with the mine yielding up to one-third of the world's silver production in the 16th century, bolstering Amago finances and attracting rival interests.[40] This resource underpinned military expansions but also invited conflicts, as silver inflows funded samurai retainers and fortifications.[41] Amago power peaked under successors like Haruhisa but collapsed amid Mori clan incursions; in 1566, after a prolonged siege, Gassan-Toda fell to Mori Motonari, leading to the clan's surrender and dispersal of their forces.[37] Iwami Ginzan subsequently passed through various hands, including Oda Nobunaga's brief oversight, before stabilizing under later warlords.[42] This era underscored Shimane's role in Japan's feudal silver economy while highlighting the volatility of provincial lordships amid national unification struggles.[41]Edo Period and Isolation

During the Edo period (1603–1868), the territory of present-day Shimane Prefecture fell mainly under the control of the Matsue Domain, a fudai domain loyal to the Tokugawa shogunate, with its seat at Matsue Castle. The castle, initiated by Horio Yoshiharu in 1607 and completed by 1611, became the administrative hub after governance passed to the Matsudaira clan—a Tokugawa kin branch—in 1638, which held authority over Izumo and parts of Hōki provinces until the Meiji Restoration.[43][44] The domain's kokudaka (assessed rice yield) reached approximately 520,000 koku by the mid-17th century, supporting a structured feudal hierarchy of samurai, merchants, and peasants focused on rice cultivation and resource extraction.[43] A pivotal economic asset was the Iwami Ginzan silver mine in western Shimane, operational since 1526 and peaking at around 38 tons of annual silver output in the 16th–17th centuries, accounting for about one-third of global production at its height. Initially under direct shogunate oversight, the mine transferred to Matsue Domain control in 1636, funding domain finances and shogunate coffers through taxation, while employing thousands in traditional smelting and refining amid the region's rugged terrain.[45][46] The shogunate's sakoku (closed country) policy, formalized from 1633–1639, enforced national isolation by prohibiting most foreign travel, trade, and Christian influences, with Shimane's Sea of Japan coastline patrolled to deter unauthorized vessels. This seclusion preserved pre-industrial techniques at Iwami Ginzan, blocking European technological imports during the Industrial Revolution and maintaining labor-intensive methods reliant on local charcoal and mercury amalgamation.[41] In Izumo, sakoku reinforced cultural continuity, safeguarding Shinto practices at sites like Izumo Taisha without external religious or ideological disruptions, while geographic remoteness from Edo and Kyoto limited broader political intrigue, fostering stable but insular domain administration.[44] The policy's end in 1853–1854 via Commodore Perry's arrival marked Shimane's gradual reorientation toward modernization, though local economies remained anchored in mining and agriculture until decline set in post-1923 mine closure.[45]Modernization and Imperial Era

Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the feudal Matsue Domain, which encompassed much of present-day eastern Shimane, was abolished on July 29, 1871, as part of the nationwide hanseki hōkan policy that transformed domains into prefectures under central government control.[47] This administrative shift integrated the former Izumo, Iwami, and Oki provinces into nascent prefectural structures, with Shimane Prefecture formally established on December 9, 1876, through mergers including the former Matsue Prefecture, and its modern boundaries solidified by 1881.[32] Matsue Castle, completed in 1611, saw most of its structures dismantled in 1875 amid the Meiji government's castle demolition orders to symbolize the end of feudalism, though its main keep was preserved due to local petitions and repurposed for military storage.[48] The Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine, a key economic asset discovered in 1526, continued operations into the Meiji and Taisho eras, with mining in major tunnels like Okubo persisting until 1896 and full closure in 1923, contributing to Japan's silver output amid early modernization efforts, though production had declined from its Edo-period peak.[49] Shimane's economy during this period remained predominantly agrarian and extractive, with limited heavy industrialization compared to coastal or urban prefectures, as the region's remote location hindered rapid infrastructure development like railways until the San'in Main Line's partial openings from 1908 onward.[50] In the Imperial era, a notable territorial expansion occurred on January 28, 1905, when the Japanese cabinet decided to incorporate the Takeshima islets (known as Dokdo in Korea) into Shimane Prefecture, citing unclaimed status and strategic needs during the Russo-Japanese War, formalized by a notice in the official gazette on April 17, 1905, placing them under Oki District administration.[51] This move asserted Japanese control over the islands for fisheries and navigation, without contemporary Korean objection documented in primary records.[52] Shimane contributed manpower to imperial military campaigns, but specific regional impacts from World War I or interwar policies are less pronounced, with the prefecture maintaining a peripheral role in Japan's expansionist pursuits until the Pacific War's end in 1945.[51]Post-War Reconstruction and Contemporary Developments

Following Japan's surrender on August 15, 1945, Shimane Prefecture experienced immediate post-war unrest, culminating in the Matsue Incident on August 24, when approximately 40 ultranationalist dissidents, led by 25-year-old Isao Okazaki, attacked and set fire to the Shimane Prefectural Office in Matsue City, protesting the acceptance of defeat and aiming to continue resistance against Allied forces.[53] The assault resulted in the office's destruction and one death, but was quickly suppressed by local police and military remnants, marking one of the last organized acts of defiance in mainland Japan.[53] Unlike urban centers, Shimane suffered no significant wartime bombing due to its lack of strategic industrial targets, minimizing physical infrastructure damage and allowing focus on administrative stabilization under U.S. occupation forces from 1945 to 1952.[54] Occupation-era reforms reshaped Shimane's agrarian economy, with land redistribution under the 1946-1949 land reform laws transferring tenancy-held fields to over 80% of former tenant farmers, enhancing rice and crop productivity in the prefecture's fertile lowlands and boosting rural stability.[55] Post-independence in 1952, Shimane participated in Japan's high-growth era (1955-1973), emphasizing primary sectors: agriculture output grew through mechanization and irrigation projects, while fisheries expanded with coastal resources in the Sea of Japan, contributing to the prefecture's GDP alongside limited manufacturing in textiles and food processing.[55] Infrastructure advancements included road networks and the completion of key bridges, such as those linking Matsue to outlying islands, facilitating trade and reducing isolation by the 1960s.[56] In the energy sector, the Shimane Nuclear Power Plant's Unit 1 (460 MW) commenced operations in March 1974 after construction began in 1970, providing a stable power base for local industry and marking Shimane's entry into nuclear development amid Japan's 1973 oil crisis response.[57] Unit 2 (820 MW) followed in 1989, though both units halted post-2011 Fukushima accident for safety upgrades, with Unit 2 restarting commercial operations on January 10, 2025, after regulatory approval.[58][59] Contemporary developments emphasize heritage preservation and tourism amid demographic challenges. The Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine and its cultural landscape, operational from 1526 to 1923, received UNESCO World Heritage designation in July 2007, spurring restoration efforts and annual visitors exceeding 500,000 by promoting historical mining sites and traditional townscapes in Oda City.[41][42] Population decline persists, with Shimane's residents falling to 671,000 by October 2020—one of Japan's lowest densities—driven by out-migration and aging, prompting initiatives like Ama Town's 2004 relocation subsidies that attracted over 20% new young residents by reversing local depopulation trends through community-led economic revitalization in fisheries and eco-tourism.[2][56] These efforts align with broader prefectural strategies to leverage natural assets, including hot springs and coastal sites, for sustainable growth, though economic reliance on primary industries limits diversification.[56]Government and Administration

Prefectural Governance Structure

Shimane Prefecture's governance follows the standard structure for Japanese prefectures, with executive authority vested in a directly elected governor and legislative functions handled by a unicameral prefectural assembly. The governor serves a four-year term and is responsible for executing prefectural policies, preparing the annual budget, managing administrative departments, and representing the prefecture in intergovernmental relations.[60] Tatsuya Maruyama, an independent, has held the office of governor since April 28, 2019, following his election in the 2019 gubernatorial race. He was reelected unopposed on April 9, 2023, securing a second term ending April 29, 2027.[61] Maruyama's administration oversees key areas such as education, welfare, infrastructure, and economic development, with a bureaucracy organized into departments including those for general affairs, finance, health, and industry.[62] The Shimane Prefectural Assembly comprises 37 members elected from designated multi-member electoral districts across the prefecture, also serving four-year terms aligned with unified local elections.[63] Assembly districts include Matsue (11 seats), Izumo (9 seats), and others corresponding to major cities and regions, ensuring representation proportional to population.[63] The assembly's primary roles involve approving the governor's budget proposals, enacting local ordinances, and conducting oversight through committees on topics like fiscal policy and public welfare; the most recent election occurred on April 9, 2023, as part of the national unified local elections.[60][64] While the assembly operates independently, cooperation with the governor is essential for effective governance, reflecting Japan's decentralized local autonomy framework established post-World War II.[60]Political Landscape and Elections

Shimane Prefecture's political landscape reflects the conservative leanings typical of rural Japanese regions, with the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) maintaining historical dominance in local governance due to factors such as agricultural interests, aging demographics, and resistance to rapid urbanization policies favored by urban opposition parties. The prefecture's voters have consistently prioritized stability and national alignment, leading to strong LDP performance in elections, though national-level scandals, including the 2023-2024 slush fund controversy, have tested this support by eroding trust in party discipline.[65][66] Tatsuya Maruyama, serving as governor since his initial election in 2019, secured re-election on April 9, 2023, during the unified local elections, running as an independent with LDP endorsement and emphasizing continuity in economic development and disaster preparedness. His administration has focused on reviving local industries amid depopulation, garnering support from conservative voters wary of opposition proposals seen as disconnected from regional needs. Maruyama's victories underscore the limited appeal of opposition parties like the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP) in gubernatorial races, where turnout often hovers around 50-60% and incumbency advantages prevail.[67][68] The Shimane Prefectural Assembly, consisting of 37 members elected every four years, remains under LDP control, with the party securing a majority in the 2023 elections alongside allies, reflecting voter preferences for policies supporting fisheries, agriculture, and nuclear energy resumption despite opposition critiques. However, the LDP experienced a setback in the April 2024 House of Representatives by-election for Shimane's 1st district, losing the seat to CDP candidate Akiko Kamei amid backlash over the party's fundraising irregularities, signaling potential vulnerabilities in what was once an unassailable conservative bastion. This loss, in a district long held by LDP figures tied to the influential Satō-Kishi-Abe political lineage, highlights how centralized scandals can disrupt local patronage networks.[69][66][65]Territorial Claims and Disputes

Shimane Prefecture asserts sovereignty over the Takeshima islets (also known as Dokdo or Liancourt Rocks), a small group of uninhabited rocks located approximately 157 kilometers northwest of the Oki Islands in the Sea of Japan, at coordinates 37°14′ north latitude and 131°52′ east longitude.[70] On January 28, 1905, the Japanese Cabinet issued a decision incorporating Takeshima into Shimane Prefecture, designating it as part of the former Oki Islands District and affirming prior Japanese sovereignty based on historical usage and maps dating to the Edo period.[71] The Japanese government maintains that Takeshima constitutes inherent national territory under international law, with no valid Korean claims predating this incorporation, and views South Korea's administration as an illegal occupation initiated in 1954 following the 1952 Syngman Rhee Line declaration.[72][73] South Korea, which has maintained de facto control since 1954 through a police garrison of around 40-50 personnel and periodic high-level visits—such as President Yoon Suk-yeol's planned oversight in 2023—rejects Japan's claims, asserting historical Korean ties from the Joseon Dynasty and interpreting the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty as excluding Takeshima from Japanese territory.[73][74] Japan has consistently protested these actions, including through diplomatic notes and referrals to the International Court of Justice in 1954 and 1962, which South Korea declined, and continues to seek resolution via bilateral talks while emphasizing peaceful means under the postwar international order.[75] Shimane Prefecture actively promotes awareness through the annual "Takeshima Day" ordinance enacted on March 16, 2005, commemorating the 1905 incorporation date of February 22, which includes educational events and protests against Korean activities, though it has strained local relations with South Korean entities.[76] No other significant territorial disputes involve Shimane Prefecture.[77]Demographics

Population Dynamics

Shimane Prefecture's population reached its historical peak of 929,000 in 1955, following post-war growth, but has since experienced consistent decline driven by Japan's broader demographic trends of low fertility and aging, compounded by rural-to-urban migration. By 2000, the population had fallen to 771,441, continuing to decrease to 781,021 by 2010 despite temporary fluctuations, and further to 671,126 as recorded in the 2020 census. This represents an approximate 28% reduction from the mid-20th-century high, reflecting structural shifts where industrial and service opportunities concentrated in metropolitan areas like Tokyo and Osaka drew away younger residents.[78][79][80] The annual population change rate averaged -0.68% between the 2015 and 2020 censuses, accelerating to around -1.27% in recent years, with the total dropping to 649,563 by 2023 and an estimated 642,590 in 2024. This contraction stems primarily from negative natural increase, where deaths exceed births due to a fertility rate below replacement levels (consistent with national patterns but intensified by the prefecture's advanced aging profile) and net out-migration, particularly of working-age individuals seeking employment elsewhere. Internal migration data indicate persistent outflows from Shimane, as rural prefectures like it offer fewer high-wage jobs in manufacturing and services compared to urban centers, leading to a feedback loop of community shrinkage and reduced local vitality.[80][81][82][83]| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1955 | 929,000 |

| 2000 | 771,441 |

| 2020 | 671,126 |

| 2023 | 649,563 |

Age and Social Structure

Shimane Prefecture has one of Japan's most aged populations, with 34.4% of residents aged 65 and older as recorded in the 2020 census, exceeding the national average of 28.9% for 2022.[80][85] The working-age group (15-64 years) comprises 50.2% of the population, while those under 18 account for the remaining 15.4%, highlighting a narrow youth base driven by persistent out-migration of younger residents to urban areas and below-replacement fertility rates.[80] This structure positions Shimane among prefectures with the lowest productive-age ratios, projected at 53.7% in medium-term estimates, amplifying labor shortages and dependency burdens.[84] The prefecture's demographic profile features a high concentration of centenarians, at 168.69 per 100,000 population in 2025, the nation's highest rate for the 13th consecutive year, reflecting elevated life expectancy linked to rural lifestyles and lower urban stressors.[86] Socially, this aging manifests in a household composition averaging 3.01 persons per unit, with increasing prevalence of elderly-only or single-elderly dwellings amid declining family sizes and delayed marriages—female first marriage age at 28.4 years.[87][11] Rural traditions like osekkai (mutual aid networks) sustain community support, mitigating isolation in low-density areas where 70.22% of households are dual-income, yet overall social participation remains challenged by depopulation.[88][11]| Age Group | Percentage (2020) |

|---|---|

| 0-17 years | 15.4% |

| 18-64 years | 50.2% |

| 65+ years | 34.4% |

Economy

Primary Sectors: Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries

Shimane Prefecture's primary sectors rely on its mountainous terrain, extensive forests covering approximately 80% of its 6,707 km² land area, and access to the Sea of Japan and Lake Shinji, supporting traditional resource-based activities despite a shift toward secondary and tertiary industries.[4] These sectors employed a notable portion of the workforce historically, with primary industry accounting for 10.1% of economic structure as of 2005, though updated figures reflect ongoing depopulation and mechanization challenges.[89] Agriculture centers on rice cultivation, supplemented by vegetables, fruits, and livestock, while forestry emphasizes sustainable timber management and forestry contributes through wooden products and non-timber outputs like mushrooms. Fisheries, bolstered by coastal and island resources, rank Shimane among Japan's top ten prefectures for catches, with Oki Islands comprising about 96% of the prefecture's haul in 2017 via methods such as round haul netting.[90] Agriculture in Shimane primarily involves paddy rice farming, adapted to the region's alluvial plains and river valleys. Efforts extend to organic production of green tea, vegetables, and fruits, with the prefecture noted for high rankings in certain organic outputs. In the Oki Islands, sloping lands facilitate livestock grazing, enabling calf exports to mainland markets, alongside localized rice development using island-specific resources. Vegetable and fruit yields for 2023 include data on key crops, though overall agricultural output faces pressures from aging farmers and limited arable land, estimated at less than 20% of total area.[91] Forestry operations draw on dense coniferous stands, including sugi (Japanese cedar), with management practices like pruning and thinning studied to enhance wood quality and strength for sawn timber. The sector supports woodenware production and mushroom cultivation, particularly in the 90% forested Oki Islands, contributing to local processing industries. Natural forest cover stood at 392,000 hectares in 2020, or about 59% of land, with annual losses of 602 hectares by 2024 equivalent to 259 kilotons of CO₂ emissions, underscoring sustainability efforts amid low domestic timber demand.[92] Fisheries thrive on abundant marine resources around the Oki Islands and mainland coast, yielding 142,154 tons in 2010, dominated by mackerel, Japanese seabream, and flying fish. Aquaculture targets offshore bivalves like shellfish and seaweed, with prefectural grants for Oki fisheries emphasizing resource regeneration. Inland, Lake Shinji produces shijimi clams and other brackish-water species among its "seven delicacies," supporting miso-based soups and preserved foods. Round haul net vessels unload primarily at nearby ports like Sakaiminato, though overfishing risks and seasonal variations necessitate regulated quotas.[93][94]Industrial and Manufacturing Base

Shimane Prefecture's manufacturing sector emphasizes electronics, precision machinery, and metal processing, contributing significantly to the regional economy through high-value exports and technological innovation. In 2022, the prefecture's gross domestic product reached approximately 2.67 trillion Japanese yen, with manufacturing playing a central role alongside primary sectors.[95] Key strengths include a cluster of electronics firms in the Izumo area, supported by the prefecture's industrial promotion initiatives and research facilities like the Shimane Institute for Industrial Technology.[4] The electronics and semiconductor subsector is prominent, driven by production of integrated circuits and related components, which accounted for over $1 billion in exports in recent years.[96] Shimane Fujitsu Limited, operational since 1990, specializes in printed circuit board manufacturing and final assembly of communication and computing equipment, maintaining integrated production within Japan.[97] Complementary firms include Izumo Murata Manufacturing Co., Ltd., which produces electronic components such as capacitors at its facility in Hikawa-cho, Izumo-shi, established in 1983 with capital of 430 million yen.[98] Shimane Shimadzu Corporation, a subsidiary focused on precision instruments, operates in the same region, emphasizing advanced manufacturing processes.[99] These operations benefit from local R&D support, fostering growth in semiconductors and electrical equipment, which have driven above-average production increases in the prefecture.[100] Metal processing and foundry industries form another pillar, leveraging Shimane's historical expertise in materials like Yasugi specialty steel (YSS), used in dies and critical components.[101] Hitachi Metals produces high-quality metal products, while Matsue Yamamoto Metal Technos handles medium- to large-scale metal fabrication.[102] Exports of cast iron products and related metals underscore this focus, with the sector noted for high technological standards in primary materials processing.[96] [4] Precision machinery manufacturing includes automatic equipment and robotics, exemplified by SHIMANEJIDOKI Co., Ltd., which designs in-house robots and processed parts with 154 employees across facilities.[103] The prefecture also excels in specialized production machinery, such as CNC gear hobbing machines, and transport components like transmissions.[101] These diverse activities, concentrated in areas like Izumo and Matsue, position Shimane as a hub for quality-oriented manufacturing rather than mass-volume output, aligning with Japan's broader shift toward high-tech regional clusters.[101]Energy Production and Nuclear Industry

Shimane Prefecture's energy production is characterized by a reliance on nuclear power for baseload generation, supplemented by hydroelectric facilities and emerging renewable sources such as wind and solar. The prefecture contributes to Japan's Chugoku region's electricity supply through the Shimane Nuclear Power Plant, which has historically provided a significant portion of low-carbon power, though operations were halted nationwide following the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi accident. Post-Fukushima regulatory reforms emphasized enhanced safety measures, including seismic reinforcements and tsunami defenses, enabling selective restarts.[104][57] The Shimane Nuclear Power Plant, located in Kashima, Matsue, is operated by Chugoku Electric Power Company and features three units. Unit 1, a boiling water reactor with 460 MW capacity, commenced commercial operation on March 29, 1974, but has remained offline since 2011 and faces potential decommissioning due to age and regulatory hurdles for older designs. Unit 2, a 789 MW boiling water reactor, restarted on December 7, 2024, after 13 years of inactivity, following approval of safety upgrades and local gubernatorial consent in June 2022; it achieved commercial operation on January 10, 2025, marking the first active nuclear reactor in the Chugoku area. Unit 3, an advanced boiling water reactor (ABWR) with approximately 1,373 MW capacity, began construction in 2007 but remains under regulatory review as of 2025, with no operational start date confirmed amid ongoing post-Fukushima assessments.[104][59][105] Beyond nuclear, Shimane generates power from hydroelectric dams, particularly along rivers like the Hi River, contributing to the prefecture's renewable mix, though specific output figures are modest compared to national hydropower leaders. Wind energy has expanded with projects such as the 48.43 MW Hamada onshore wind farm and the 20.7 MW Gotsu-Takanoyama facility, operational since 2009, supporting local targets for 180,000 kW of wind capacity by mid-decade. Solar photovoltaic installations align with prefectural goals of 18,000 kW by 2008 (achieved and expanded), while biomass from forestry residues adds minor contributions. These renewables, however, constitute a smaller share than nuclear when the latter is active, reflecting Japan's broader energy strategy prioritizing stable, high-density sources amid geographic constraints on large-scale wind and solar.[106][107][108]Services, Retail, and Emerging Sectors

The service sector forms the backbone of Shimane Prefecture's economy, with retail comprising its largest component due to the prefecture's relatively low land costs and proximity to water resources that support logistics and distribution.[4] This dominance reflects Shimane's rural character and limited manufacturing scale compared to urban prefectures, where services absorb much of the local workforce amid a shrinking population.[4] Tourism, a prominent service subsector, capitalizes on cultural assets like Izumo Taisha shrine and Matsue Castle but generates modest revenue, with the prefecture capturing just 0.07% of Japan's national guest nights in recent tallies.[109] Efforts to expand this include the Shimane Tourism Summit held on September 3, 2025, which targeted inbound visitors through promotional strategies and infrastructure enhancements.[109] Despite these initiatives, Shimane ranks among Japan's least-visited prefectures, constrained by geographic isolation and competition from more accessible destinations.[109] Retail operations, centered in urban hubs like Matsue, emphasize local chains and supermarkets serving daily consumer needs in a demographically aging region.[4] The sector benefits from stable domestic demand but faces challenges from online competition and outmigration, prompting prefectural incentives for business retention. Emerging sectors focus on information technology and open innovation, with Matsue positioning itself as a hub for tech and logistics development to diversify beyond traditional industries.[110] The Shimane IT Open-Innovation Center drives software research and collaborative ventures, building on local strengths in programming languages like Ruby and fostering startups through public-private partnerships.[111] [112] Additional momentum comes from initiatives like the Next Generation Tatara Co-Creation Center, which applies open innovation to advanced manufacturing techniques such as 3D additive printing.[113] These efforts aim to attract investment and counter economic stagnation, though growth remains nascent amid Shimane's peripheral location.[114]Trade and Recent Economic Trends

Shimane Prefecture's exports are dominated by manufactured goods, particularly dissolving grades chemical wood pulp valued at $2.79 billion USD, cars at $1.45 billion USD, and unprocessed artificial staple fibers at $916 million USD in 2024.[96] Total exports for the year amounted to $6.76 billion USD, positioning the prefecture as Japan's smallest exporter by volume among its 47 regions, reflecting its focus on niche industrial processing rather than high-volume assembly.[96] Primary export destinations include China and South Korea, with shipments to China reaching ¥410 million in July 2025 and to South Korea ¥189 million in the same period.[96] Imports into Shimane primarily comprise raw materials essential for local industries, such as coal briquettes and fuel wood, alongside chlorides for chemical processing.[96] Key suppliers are resource-rich nations like Canada (¥1.95 billion in July 2025) and Australia (¥1.55 billion), underscoring the prefecture's reliance on imported energy and inputs to support its materials manufacturing cluster, including steel and semiconductor-related production.[96] This import profile contributes to a persistent trade deficit, as evidenced by a negative balance of approximately $45 million USD in July 2025.[96] Recent economic trends show export volumes surging 148% year-over-year to ¥608 million in July 2025, driven by recovery in global demand for Shimane's specialized outputs amid Japan's post-pandemic industrial rebound.[96] However, imports declined 22.3% over the same timeframe, partly due to optimized supply chains and fluctuating commodity prices.[96] These shifts align with broader prefectural efforts to enhance manufacturing competitiveness through clusters in primary materials and electronics, though structural challenges like workforce aging and rural depopulation constrain sustained growth, with per capita GDP remaining among Japan's lower tiers at approximately ¥3.71 million in recent estimates.[6]Infrastructure and Transportation

Road and Highway Networks

Shimane Prefecture maintains a road network spanning approximately 18,295 kilometers, characterized by high density relative to its land area, which supports connectivity across mountainous and coastal terrains.[115] This infrastructure includes national highways, prefectural roads, and municipal routes, with expressways playing a critical role in linking urban centers like Matsue and Izumo to neighboring prefectures. The network facilitates logistics, tourism, and daily mobility in a predominantly rural region, where road transport predominates due to limited rail options in remote areas.[116] The San'in Expressway (E9) forms a key coastal artery, extending through Shimane as part of a route connecting Tottori to Yamaguchi prefectures and paralleling National Highway 9. Sections operational in Shimane, such as those near Matsue and Oda, provide high-speed access to sites like Izumo Taisha Shrine and Iwami Ginzan, while serving as a redundancy during disruptions on parallel routes like National Highway 9, as demonstrated during a 2021 landslide closure in Izumo City.[116][117] The Matsue Expressway complements this by branching inland from Matsue toward Unnan and connecting to the broader Chūgoku Expressway system (E2), enhancing inter-prefectural travel toward Hiroshima.[117] National Highway 9 traverses the prefecture longitudinally, serving as the backbone for local traffic and freight along the San'in coast, with improvements like bypasses aiding flow through urban areas. Other significant routes include National Highway 54, linking Matsue southward to Hiroshima, and National Highway 180, supporting eastern connectivity. Recent developments, such as extensions in the Chūgoku region, have improved logistics efficiency, with a 137-kilometer north-south highway through the Chūgoku Mountains—connecting Hiroshima and Shimane—boosting tourism and goods transport since its completion around 2015.[116][118] These arteries underscore the prefecture's reliance on roads for economic integration, though ongoing construction reflects challenges in fully realizing expressway plans amid terrain constraints.[119]Rail and Public Transit

The rail infrastructure in Shimane Prefecture centers on the San'in Main Line, operated by West Japan Railway Company (JR West), which parallels the Sea of Japan coast and connects eastern entry points from Tottori Prefecture through key stations including Matsue, Izumo-shi, and Masuda in the west.[120][121] This line supports local and regional passenger services, with daily operations handling commuter demand in urban centers like Matsue and Izumo while extending to rural areas; limited express trains, such as those linking to Yonago and beyond, provide faster connections to adjacent prefectures.[120] Complementing JR services, the private Ichibata Electric Railway maintains a 42-kilometer route linking Izumo City to Matsue, operational since its establishment in 1912, and noted for scenic passages along Lake Shinji that enhance tourism alongside practical transport.[122] This line integrates with JR at endpoints, facilitating transfers for passengers accessing sites like Izumo Taisha Shrine.[123] Public transit beyond rail relies heavily on bus operations, with Ichibata Bus and municipal providers like Matsue City Transportation Bureau offering intra-city and inter-municipal routes to underserved areas; services remain infrequent due to the prefecture's sparse population and geography, often requiring timetable verification for reliability.[124][125] Community buses, such as the Yakumo service, further extend coverage in remote locales, though overall network density prioritizes road over rail for non-coastal travel.[125]Airports, Ports, and Ferries

Izumo Airport (also known as Izumo Enmusubi Airport), located in the Hikawa district of Izumo city, serves as the primary gateway for eastern Shimane Prefecture, with regular domestic flights from Tokyo's Haneda Airport operated by All Nippon Airways, taking approximately 1 hour and 30 minutes.[126][127] The airport handles around 500,000 passengers annually and connects to key sites like Izumo Taisha Shrine via shuttle buses.[128] Iwami Airport, situated near Masuda city in western Shimane, provides domestic services primarily to Osaka's Itami Airport and other regional hubs, facilitating access to the Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine UNESCO site.[129] It features a single 2,000-meter runway and supports limited cargo operations alongside passenger flights.[130] Oki Airport on Dōgo Island caters to the remote Oki Islands chain, offering seasonal flights from Izumo and Yonago airports in neighboring prefectures, with a focus on tourism to the UNESCO Global Geopark.[129] The facility includes a 1,200-meter runway suitable for small propeller aircraft.[130] Hamada Port, on the Sea of Japan coast in Hamada city, functions as a regional commercial and fishing hub, handling cargo such as marine products and supporting cruise ship calls midway between Hakata and Sakai ports.[131] It features berths for vessels up to 10,000 gross tons and contributes to local fisheries outputting over 20,000 tons of seafood annually.[132] Port of Masuda, in Masuda city, primarily serves fishing and small-scale cargo needs, with infrastructure for coastal trade and proximity to the western prefectural border.[132] The port includes facilities for ferry connections and handles regional exports like agricultural goods. Shichirui Port, on the Shimane Peninsula, acts as the main departure point for maritime access to the Oki Islands, accommodating ferries and high-speed vessels with daily services.[133] Ferry services in Shimane primarily connect the mainland to the Oki Islands via Oki Kisen operators, including the Ferry Oki departing Shichirui Port at 9:00 a.m. for a 2-hour 25-minute voyage to Saigō Port on Dōgo Island, with fares around ¥2,920 one-way.[134] High-speed options like the Rainbow Jet hydrofoil reduce travel time to about 1 hour 10 minutes from Shichirui to Oki ports.[124] Inter-island routes, such as those between Nakanoshima, Nishinoshima, and Chiburijima using smaller vessels like the Isokaze, operate multiple times daily for local transport.[135] Saigō Port on Dōgo serves as the Oki Islands' central marine hub for logistics and passenger arrivals.[136]Recent Infrastructure Projects

In June 2025, Internet Initiative Japan (IIJ) commenced operations at a new System Module Building within the Matsue Data Center Park in Matsue City, Shimane Prefecture, adding approximately 300 rack equivalents of capacity to the existing 400 racks.[137] Construction of the modular facility began in February 2024, incorporating energy-efficient external air cooling, substantial renewable energy integration, and uninterruptible power systems designed for disaster resilience, including potential community power supply during emergencies.[137][138] This expansion supports Shimane's designation as a leading decarbonization region by Japan's Ministry of the Environment, aligning with broader goals for sustainable digital infrastructure amid regional economic revitalization efforts involving local firms like TSK Group.[137][139] Izumo Airport, serving Izumo and nearby Matsue, announced plans in early 2025 to expand its boarding lounge to address congestion and prepare for potential international flights, enhancing accessibility for the prefecture's tourism and logistics sectors.[140] This initiative follows prior improvements in parking and signage, reflecting ongoing investments to boost regional connectivity in a prefecture with limited high-speed transport options.[141] Deck slab renewal on the Tadeno No. 2 Bridge in Kanoashi District, Shimane Prefecture, was completed as part of maintenance efforts on aging infrastructure, earning recognition from the Japan Prestressed Concrete Institute in 2022 for innovative techniques in slab replacement on the outbound lane.[142] Such projects address the prefecture's estimated 1.7 trillion yen need for infrastructure upkeep over 30 years starting in fiscal 2025, prioritizing longevity amid seismic risks in western Japan.[142][143] Extensions to the San'in Expressway continue to improve north-south linkages across Shimane, connecting it more directly to Hiroshima and Kansai regions, with recent segments enhancing logistics and tourism flows as evidenced by the decade-old Chugoku Yamanami Highway's impacts.[109][118] These developments, under the Chugoku Regional Development Bureau's oversight, focus on high-standard trunk roads to mitigate geographic isolation.[144]Culture and Society

Historical and Cultural Heritage

Shimane Prefecture holds a central place in ancient Japanese mythology, as documented in the Kojiki, Japan's oldest chronicle compiled in 712 CE, where approximately one-third of the recorded myths are set in the Izumo region.[145] These narratives describe Izumo as the "land of the gods," featuring deities such as Okuninushi, the kami associated with nation-building, marriage, and the underworld, who ceded control of Japan to the imperial lineage at Inasa-no-hama Beach.[146] Artifacts from this era, including bronze swords and ritual objects, are exhibited at the Shimane Museum of Ancient Izumo, underscoring the region's role in early Shinto practices and pre-Yamato governance structures.[147] Izumo Taisha Grand Shrine, located in Izumo City, exemplifies this heritage as one of Japan's most ancient and venerated Shinto sites, with origins predating written records and mentions in eighth-century texts.[148] Dedicated primarily to Okuninushi, the shrine employs the distinctive taisha-zukuri architectural style, characterized by massive timber construction without nails, and hosts an annual kamiari festival in October (November by lunar calendar), during which all Japanese deities purportedly gather.[149] Its main hall, rebuilt in the 18th century following earlier structures potentially dating to the 7th century, symbolizes continuity in indigenous spiritual traditions predating centralized imperial influence.[150] In the feudal era, Shimane's strategic coastal position fostered defensive architecture, most notably Matsue Castle, constructed from 1607 to 1611 under daimyo Horio Yoshiharu on the site of an earlier fortification.[151] One of only twelve extant original castles in Japan, its black-walled keep—designated a National Treasure—survived the Meiji-era dismantling of fortifications, preserving Edo-period engineering with features like stone walls and moats integrated into the urban landscape of Matsue.[48] The castle served as the seat of the Matsudaira clan, descendants of Tokugawa Ieyasu, until 1871, reflecting the domain's administrative and military functions amid post-Sekigahara stability.[152] Economic heritage is embodied by the Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine in Oda City, operational from its discovery in 1526 until 1923, which supplied up to one-third of the world's silver output during the 16th century.[41] This output fueled Japan's trade with Southeast Asia and Europe's Manila galleons, driving regional prosperity through mining techniques like drainage adits and the development of the nearby port town of Omori.[40] Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2007 for its cultural landscape—including ruins like the Shimizudani Refinery—the site illustrates the interplay of resource extraction, labor organization, and environmental adaptation in early modern Japan.[41]Local Dialects and Traditions

The dialects of Shimane Prefecture form part of the San'in subgroup within Western Japanese dialects, exhibiting phonological traits such as vowel mergers and distinct verb conjugations differing from Tokyo-standard Japanese. In the eastern and central areas, encompassing Izumo City, Matsue City, Unnan City, Yasugi City, and Okuizumo, the Izumo dialect prevails, with lexical items and intonational patterns tied to regional history.[153] Western Shimane, particularly the Iwami region, features the Iwami dialect, marked by conservative grammar and vocabulary influenced by historical isolation and mining communities.[154] The Oki Islands off the northern coast host variants of the Unpaku dialect group, sharing central San'in features like aspirated consonants but adapted to insular speech patterns.[154] Local speech often incorporates culturally specific expressions, such as the evening greeting "Banjimashite," used in Izumo to acknowledge the transition to dusk, reflecting mythological associations with divine assemblies at twilight.[155] These dialects persist in rural communities and family interactions, though urbanization and media exposure have promoted code-switching to standard Japanese among younger residents and in formal settings.[156] Shimane's traditions derive from ancient Shinto practices and folklore chronicled in the Kojiki (712 CE), positioning the prefecture as the epicenter of Japanese creation myths, including the deity Ōkuninushi's land-pulling feats in Izumo.[157] Kagura, ritual dances performed to appease gods with rhythmic drumming and masked enactments of mythic battles, originated here as shrine offerings and continue in annual ceremonies at sites like Izumo Taisha, preserving pre-Heian performative arts.[1] In Okuizumo, the tatara furnace process—smelting iron sand with charcoal in traditional bloomeries—endures as a living craft, yielding high-carbon steel for tools and swords, with operational forges demonstrating techniques dating to the 6th century.[158] The kamiarizuki (month of gods' gathering) custom, observed in the tenth lunar month, alters local calendars by shifting "empty months" elsewhere in Japan, influencing communal rituals and reinforcing Izumo's role as a spiritual hub.[1] These elements, sustained through community transmission rather than institutional mandates, highlight causal links between geographic seclusion and cultural retention.[159]Festivals and Intangible Assets

Shimane Prefecture hosts several traditional festivals rooted in Shinto rituals and local folklore, particularly centered around its ancient shrines. The most prominent is the Kamiari-sai (God-Gathering Festival) at Izumo Taisha Grand Shrine, held annually in the tenth month of the lunar calendar, typically spanning late October to mid-November, with key ceremonies from November 29 to December 15. This event commemorates the annual assembly of Japan's eight million kami (deities), who purportedly gather at Izumo to deliberate on human fortunes, marriages, and harvests, a belief unique to this shrine and contrasting with the "Month of Emptiness" observed elsewhere in Japan during the same period.[160][161] Other notable festivals include the Horan-enya at Jozan Inari Shrine in Matsue, one of Japan's three major portable shrine boat processions, featuring over 20 boats carrying mikoshi (divine palanquins) along the Hiikawa River in late May or early June, accompanied by rhythmic chanting and drumming to invoke prosperity.[162] In summer, the Tenjin Matsuri at Shirakata Tenmangu Shrine on July 24–25 reenacts historical processions with mikoshi parades and traditional music, dating back 400 years. Autumn brings Matsue's three key events, such as the Nakanomiya O-Matsuri with lion dances and the Suigosai fireworks display launching 10,000 shells over Lake Shinji, reflecting local aquatic heritage.[163][164] Shimane's intangible cultural assets emphasize performing arts and crafts tied to Shinto worship and historical trades. Sada Shin Noh, a sacred masked dance performed biennially at Sada Shrine in Matsue since the 9th century, was inscribed on UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2011; it involves performers in deer-skin costumes enacting myths with swords, bells, and deity masks, serving as the foundational form for Izumo-style kagura.[165] Iwami Kagura, originating in the western Iwami region, comprises dynamic ritual dances depicting epic battles from Japanese mythology, characterized by rapid footwork, vibrant costumes, and taiko drumming; designated a National Important Intangible Folk Cultural Property, it sustains over 140 troupes performing year-round for purification and community rites.[166][167] Craft traditions include Sekishu Banshi, a handmade washi paper from the Iwami area with a 1,300-year history using kozo bark and mountain streams for durability and texture, recognized under UNESCO's washi craftsmanship element since 2014 and praised for archival quality in historical documents. Masuda ningyo, wooden string puppets from Masuda City, were designated a prefectural intangible folk asset in 1964, featuring intricate manipulations in storytelling performances derived from local legends. These assets preserve Shimane's syncretic Shinto heritage amid modernization pressures.[168][169][170]Education and Research

Higher Education Institutions

Shimane University, a national institution founded in 1949, serves as the prefecture's flagship higher education provider with campuses in Matsue and Izumo.[171] The Matsue campus hosts six undergraduate faculties—Law and Literature, Education, Human Sciences, Science and Engineering, Life and Environmental Science (encompassing Materials Science and Biological Resource Sciences)—while the Izumo campus is dedicated to the Faculty of Medicine.[171] Graduate programs span similar disciplines, emphasizing regional contributions in fields like environmental science and medical research, with a total enrollment exceeding 6,000 students as of recent data.[172] The University of Shimane, a public prefectural university established in 2000 from predecessors dating to 1993, operates campuses in Matsue and Hamada, focusing on practical, community-oriented education.[173] It features two primary faculties: Policy Management, which addresses administrative and economic policy with an international lens, and Nursing, prioritizing healthcare training aligned with local demographic needs in an aging population.[174] The institution aims to cultivate graduates who integrate global perspectives into regional problem-solving, maintaining a smaller scale with emphasis on interdisciplinary research in social welfare and management.[174] Beyond these universities, Shimane hosts limited specialized higher education options, including junior colleges affiliated with the University of Shimane, but no additional full universities are accredited in the prefecture.[175] Enrollment trends reflect Shimane's rural demographics, with institutions prioritizing retention of local talent through targeted programs in agriculture, healthcare, and public administration rather than broad expansion.[176]Innovation and IT Initiatives

Shimane Prefecture has pursued targeted programs to bolster its IT sector amid rural economic challenges, emphasizing human resource development and technological upgrades to enable profitable business models and youth employment. The Shimane IT Industry Promotion Project, administered by the prefectural government, provides subsidies and support for IT firms to enhance skills, adopt advanced tools, and transition to high-value operations, with a focus on sustainable growth in a region historically reliant on traditional industries.[177] A cornerstone initiative is the Shimane Software Research and Development Center, founded in 2015 under the Shimane Industrial Promotion Foundation, which facilitates software innovation, collaborative R&D, and open innovation partnerships to spawn new IT ventures and integrate technology into local manufacturing. Complementing this, the Shimane DX Promotion Project offers consultations on digital transformation strategies, including IT tool selection and implementation, primarily through the center to aid small and medium enterprises in modernizing operations.[114][178] Infrastructure developments underscore these efforts, notably the Matsue Data Center Park in the capital, where Internet Initiative Japan commenced operations in the System Module Building—a pioneering container-module data center—in June 2025, following construction start in February 2024, to accommodate surging cloud computing needs and attract tech investments. Prefectural incentives, including tax breaks and grants, target tech startups and logistics firms, aiming to centralize innovation in Matsue while leveraging Shimane's low costs and stable power supply relative to urban centers.[137][110]Tourism and Attractions

Key Tourist Sites