Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Small molecule

View on WikipediaIn molecular biology and pharmacology, a small molecule or micromolecule is a low molecular weight (≤ 1000 daltons[1]) organic compound that may regulate a biological process, with a size on the order of 1 nm[citation needed]. Many drugs are small molecules; the terms are equivalent in the literature. Larger structures such as nucleic acids and proteins, and many polysaccharides are not small molecules, although their constituent monomers (ribo- or deoxyribonucleotides, amino acids, and monosaccharides, respectively) are often considered small molecules. Small molecules may be used as research tools to probe biological function as well as leads in the development of new therapeutic agents. Some can inhibit a specific function of a protein or disrupt protein–protein interactions.[2]

Pharmacology usually restricts the term "small molecule" to molecules that bind specific biological macromolecules and act as an effector, altering the activity or function of the target. Small molecules can have a variety of biological functions or applications, serving as cell signaling molecules, drugs in medicine, pesticides in farming, and in many other roles. These compounds can be natural (such as secondary metabolites) or artificial (such as antiviral drugs); they may have a beneficial effect against a disease (such as drugs) or may be detrimental (such as teratogens and carcinogens).

Molecular weight cutoff

[edit]The upper molecular-weight limit for a small molecule is approximately 900 daltons, which allows for the possibility to rapidly diffuse across cell membranes so that it can reach intracellular sites of action.[1][3] This molecular weight cutoff is also a necessary but insufficient condition for oral bioavailability as it allows for transcellular transport through intestinal epithelial cells. In addition to intestinal permeability, the molecule must also possess a reasonably rapid rate of dissolution into water and adequate water solubility and moderate to low first pass metabolism. A somewhat lower molecular weight cutoff of 500 daltons (as part of the "rule of five") has been recommended for oral small molecule drug candidates based on the observation that clinical attrition rates are significantly reduced if the molecular weight is kept below this limit.[4][5]

Drugs

[edit]Most pharmaceuticals are small molecules, although some drugs can be proteins (e.g., insulin and other biologic medical products). With the exception of therapeutic antibodies, many proteins are degraded if administered orally and most often cannot cross cell membranes. Small molecules are more likely to be absorbed, although some of them are only absorbed after oral administration if given as prodrugs. One advantage that small molecule drugs (SMDs) have over "large molecule" biologics is that many small molecules can be taken orally whereas biologics generally require injection or another parenteral administration.[6] Small molecule drugs are also typically simpler to manufacture and cheaper for the purchaser. A downside is that not all targets are amenable to modification with small-molecule drugs; bacteria and cancers are often resistant to their effects.[7]

Secondary metabolites

[edit]A variety of organisms including bacteria, fungi, and plants, produce small molecule secondary metabolites also known as natural products, which play a role in cell signaling, pigmentation and in defense against predation. Secondary metabolites are a rich source of biologically active compounds and hence are often used as research tools and leads for drug discovery.[8] Examples of secondary metabolites include:

- Alkaloids

- Glycosides

- Lipids

- Nonribosomal peptides, such as actinomycin-D

- Phenazines

- Natural phenols (including flavonoids)

- Polyketide

- Terpenes and terpenoids, including steroids

- Tetrapyrroles.

Research tools

[edit]

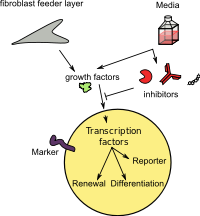

Enzymes and receptors are often activated or inhibited by endogenous protein, but can be also inhibited by endogenous or exogenous small molecule inhibitors or activators, which can bind to the active site or on the allosteric site.[citation needed]

An example is the teratogen and carcinogen phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, which is a plant terpene that activates protein kinase C, which promotes cancer, making it a useful investigative tool.[10] There is also interest in creating small molecule artificial transcription factors to regulate gene expression, examples include wrenchnolol (a wrench shaped molecule).[11]

Binding of ligand can be characterised using a variety of analytical techniques such as surface plasmon resonance, microscale thermophoresis[12] or dual polarisation interferometry to quantify the reaction affinities and kinetic properties and also any induced conformational changes.

Anti-genomic therapeutics

[edit]Small-molecule anti-genomic therapeutics, or SMAT, refers to a biodefense technology that targets DNA signatures found in many biological warfare agents. SMATs are new, broad-spectrum drugs that unify antibacterial, antiviral and anti-malarial activities into a single therapeutic that offers substantial cost benefits and logistic advantages for physicians and the military.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Macielag MJ (2012). "Chemical properties of antibacterials and their uniqueness". In Dougherty TJ, Pucci MJ (eds.). Antibiotic Discovery and Development. Springer. pp. 801–802. ISBN 978-1-4614-1400-1.

The majority of [oral] drugs from the general reference set have molecular weights below 550. In contrast the molecular-weight distribution of oral antibacterial agents is bimodal: 340–450 Da but with another group in the 700–900 molecular weight range.

- ^ Arkin MR, Wells JA (April 2004). "Small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: progressing towards the dream". Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 3 (4): 301–17. doi:10.1038/nrd1343. PMID 15060526. S2CID 13879559.

- ^ Veber DF, Johnson SR, Cheng HY, Smith BR, Ward KW, Kopple KD (June 2002). "Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates". J. Med. Chem. 45 (12): 2615–23. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.606.5270. doi:10.1021/jm020017n. PMID 12036371.

- ^ Lipinski CA (December 2004). "Lead-and drug-like compounds: the rule-of-five revolution". Drug Discovery Today: Technologies. 1 (4): 337–341. doi:10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007. PMID 24981612.

- ^ Leeson PD, Springthorpe B (November 2007). "The influence of drug-like concepts on decision-making in medicinal chemistry". Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 6 (11): 881–90. doi:10.1038/nrd2445. PMID 17971784. S2CID 205476574.

- ^ Samanen J (2013). "Chapter 5.2 How do SMDs differ from biomolecular drugs?". In Ganellin CR, Jefferis R, Roberts SM (eds.). Introduction to Biological and Small Molecule Drug Research and Development: theory and case studies (Kindle ed.). New York: Academic Press. pp. 161–203. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-397176-0.00005-4. ISBN 978-0-12-397176-0.

Table 5.13: Route of Administration: Small Molecules: oral administration usually possible; Biomolecules: Usually administered parenterally

- ^ Ngo, Huy X.; Garneau-Tsodikova, Sylvie (23 April 2018). "What are the drugs of the future?". MedChemComm. 9 (5): 757–758. doi:10.1039/c8md90019a. ISSN 2040-2503. PMC 6072476. PMID 30108965.

- ^ Atta-ur-Rahman, ed. (2012). Studies in Natural Products Chemistry. Vol. 36. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53836-9.

- ^ Mfopou JK, De Groote V, Xu X, Heimberg H, Bouwens L (May 2007). "Sonic hedgehog and other soluble factors from differentiating embryoid bodies inhibit pancreas development". Stem Cells. 25 (5): 1156–65. doi:10.1634/stemcells.2006-0720. PMID 17272496. S2CID 32726998.

- ^ Voet JG, Voet D (1995). Biochemistry. New York: J. Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-58651-7.

- ^ Koh JT, Zheng J (September 2007). "The new biomimetic chemistry: artificial transcription factors". ACS Chem. Biol. 2 (9): 599–601. doi:10.1021/cb700183s. PMID 17894442.

- ^ Wienken CJ, Baaske P, Rothbauer U, Braun D, Duhr S (2010). "Protein-binding assays in biological liquids using microscale thermophoresis". Nat Commun. 1 (7) 100. Bibcode:2010NatCo...1..100W. doi:10.1038/ncomms1093. PMID 20981028.

- ^ Levine DS (2003). "Bio-defense company re-ups". San Francisco Business Times. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

External links

[edit]- Small+Molecule+Libraries at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)