Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

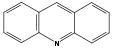

Alkaloid

View on Wikipedia

Alkaloids are a broad class of naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.[2]

Alkaloids are produced by a large variety of organisms including bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals.[3] They can be purified from crude extracts of these organisms by acid-base extraction, or solvent extractions followed by silica-gel column chromatography.[4] Alkaloids have a wide range of pharmacological activities including antimalarial (e.g. quinine), antiasthma (e.g. ephedrine), anticancer (e.g. homoharringtonine),[5] cholinomimetic (e.g. galantamine),[6] vasodilatory (e.g. vincamine), antiarrhythmic (e.g. quinidine), analgesic (e.g. morphine),[7] antibacterial (e.g. chelerythrine),[8] and antihyperglycemic activities (e.g. berberine).[9][10] Many have found use in traditional or modern medicine, or as starting points for drug discovery. Other alkaloids possess psychotropic (e.g. psilocin) and stimulant activities (e.g. cocaine, caffeine, nicotine, theobromine),[11] and have been used in entheogenic rituals or as recreational drugs. Alkaloids can be toxic (e.g. atropine, tubocurarine).[12] Although alkaloids act on a diversity of metabolic systems in humans and other animals, they almost uniformly evoke a bitter taste.[13]

The boundary between alkaloids and other nitrogen-containing natural compounds is not clear-cut.[14] Most alkaloids are basic, although some have neutral[15] and even weakly acidic properties.[16] In addition to carbon, hydrogen and nitrogen, alkaloids may also contain oxygen or sulfur. Rarer still, they may contain elements such as phosphorus, chlorine, and bromine.[17] Compounds like amino acid peptides, proteins, nucleotides, nucleic acid, amines, and antibiotics are usually not called alkaloids.[15] Natural compounds containing nitrogen in the exocyclic position (mescaline, serotonin, dopamine, etc.) are usually classified as amines rather than as alkaloids.[18] Some authors, however, consider alkaloids a special case of amines.[19][20][21]

Naming

[edit]

The name "alkaloids" (German: Alkaloide) was introduced in 1819 by German chemist Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Meissner, and is derived from late Latin root alkali and the Greek-language suffix -οειδής -('like').[nb 1] However, the term came into wide use only after the publication of a review article, by Oscar Jacobsen in the chemical dictionary of Albert Ladenburg in the 1880s.[22][23]

There is no unique method for naming alkaloids.[24] Many individual names are formed by adding the suffix "ine" to the species or genus name.[25] For example, atropine is isolated from the plant Atropa belladonna; strychnine is obtained from the seed of the Strychnine tree (Strychnos nux-vomica L.).[17] Where several alkaloids are extracted from one plant their names are often distinguished by variations in the suffix: "idine", "anine", "aline", "inine" etc. There are also at least 86 alkaloids whose names contain the root "vin" because they are extracted from vinca plants such as Vinca rosea (Catharanthus roseus);[26] these are called vinca alkaloids.[27][28][29]

History

[edit]

Alkaloid-containing plants have been used by humans since ancient times for therapeutic and recreational purposes. For example, medicinal plants have been known in Mesopotamia from about 2000 BC.[30] The Odyssey of Homer referred to a gift given to Helen by the Egyptian queen, a drug bringing oblivion. It is believed that the gift was an opium-containing drug.[31] A Chinese book on houseplants written in 1st–3rd centuries BC mentioned a medical use of ephedra and opium poppies.[32] Also, coca leaves have been used by Indigenous South Americans since ancient times.[33]

Extracts from plants containing toxic alkaloids, such as aconitine and tubocurarine, were used since antiquity for poisoning arrows.[30]

Studies of alkaloids began in the 19th century. In 1804, the German chemist Friedrich Sertürner isolated from opium a "soporific principle" (Latin: principium somniferum), which he called "morphium", referring to Morpheus, the Greek god of dreams; in German and some other Central-European languages, this is still the name of the drug. The term "morphine", used in English and French, was given by the French physicist Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac.

A significant contribution to the chemistry of alkaloids in the early years of its development was made by the French researchers Pierre Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou, who discovered quinine (1820) and strychnine (1818). Several other alkaloids were discovered around that time, including xanthine (1817), atropine (1819), caffeine (1820), coniine (1827), nicotine (1828), colchicine (1833), sparteine (1851), and cocaine (1860).[34] The development of the chemistry of alkaloids was accelerated by the emergence of spectroscopic and chromatographic methods in the 20th century, so that by 2008 more than 12,000 alkaloids had been identified.[35]

The first complete synthesis of an alkaloid was achieved in 1886 by the German chemist Albert Ladenburg. He produced coniine by reacting 2-methylpyridine with acetaldehyde and reducing the resulting 2-propenyl pyridine with sodium.[36][37]

Classifications

[edit]

Compared with most other classes of natural compounds, alkaloids are characterized by a great structural diversity. There is no uniform classification.[38] Initially, when knowledge of chemical structures was lacking, botanical classification of the source plants was relied on. This classification is now considered obsolete.[17][39]

More recent classifications are based on similarity of the carbon skeleton (e.g., indole-, isoquinoline-, and pyridine-like) or biochemical precursor (ornithine, lysine, tyrosine, tryptophan, etc.).[17] However, they require compromises in borderline cases;[38] for example, nicotine contains a pyridine fragment from nicotinamide and a pyrrolidine part from ornithine[40] and therefore can be assigned to both classes.[41]

Alkaloids are often divided into the following major groups:[42]

- "True alkaloids" contain nitrogen in the heterocycle and originate from amino acids.[43] Their characteristic examples are atropine, nicotine, and morphine. This group also includes some alkaloids that besides the nitrogen heterocycle contain terpene (e.g., evonine[44]) or peptide fragments (e.g. ergotamine[45]). The piperidine alkaloids coniine and coniceine may be regarded as true alkaloids (rather than pseudoalkaloids: see below)[46] although they do not originate from amino acids.[47]

- "Protoalkaloids", which contain nitrogen (but not the nitrogen heterocycle) and also originate from amino acids.[43] Examples include mescaline, adrenaline and ephedrine.

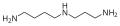

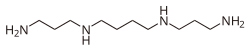

- Polyamine alkaloids – derivatives of putrescine, spermidine, and spermine.

- Peptide and cyclopeptide alkaloids.[48]

- Pseudoalkaloids – alkaloid-like compounds that do not originate from amino acids.[49] This group includes terpene-like and steroid-like alkaloids,[50] as well as purine-like alkaloids such as caffeine, theobromine, theacrine and theophylline.[51] Some authors classify ephedrine and cathinone as pseudoalkaloids. Those originate from the amino acid phenylalanine, but acquire their nitrogen atom not from the amino acid but through transamination.[51][52]

Some alkaloids do not have the carbon skeleton characteristic of their group. So, galanthamine and homoaporphines do not contain isoquinoline fragment, but are, in general, attributed to isoquinoline alkaloids.[53]

Main classes of monomeric alkaloids are listed in the table below:

| Class | Major groups | Main synthesis steps | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids with nitrogen heterocycles (true alkaloids) | |||

Pyrrolidine derivatives[54]

|

Ornithine or arginine → putrescine → N-methylputrescine → N-methyl-Δ1-pyrroline[55] | Cuscohygrine, hygrine, hygroline, stachydrine[54][56] | |

Tropane derivatives[57]

|

Atropine group Substitution in positions 3, 6 or 7 |

Ornithine or arginine → putrescine → N-methylputrescine → N-methyl-Δ1-pyrroline[55] | Atropine, scopolamine, hyoscyamine[54][57][58] |

| Cocaine group Substitution in positions 2 and 3 |

Cocaine, ecgonine[57][59] | ||

Pyrrolizidine derivatives[60]

|

Non-esters | In plants: ornithine or arginine → putrescine → homospermidine → retronecine[55] | Retronecine, heliotridine, laburnine[60][61] |

| Complex esters of monocarboxylic acids | Indicine, lindelophin, sarracine[60] | ||

| Macrocyclic diesters | Platyphylline, trichodesmine[60] | ||

| 1-aminopyrrolizidines (lolines) | In fungi: L-proline + L-homoserine → N-(3-amino-3-carboxypropyl)proline → norloline[62][63] | Loline, N-formylloline, N-acetylloline[64] | |

Piperidine derivatives[65]

|

Lysine → cadaverine → Δ1-piperideine[66] | Sedamine, lobeline, anaferine, piperine[46][67] | |

| Octanoic acid → coniceine → coniine[47] | Coniine, coniceine[47] | ||

| Quinolizidine derivatives[68][69]

|

Lupinine group | Lysine → cadaverine → Δ1-piperideine[70] | Lupinine, nupharidin[68] |

| Cytisine group | Cytisine[68] | ||

| Sparteine group | Sparteine, lupanine, anahygrine[68] | ||

| Matrine group. | Matrine, oxymatrine, allomatridine[68][71][72] | ||

| Ormosanine group | Ormosanine, piptantine[68][73] | ||

Indolizidine derivatives[74]

|

Lysine → δ-semialdehyde of α-aminoadipic acid → pipecolic acid → 1 indolizidinone[75] | Swainsonine, castanospermine[76] | |

Pyridine derivatives[77][78]

|

Simple derivatives of pyridine | Nicotinic acid → dihydronicotinic acid → 1,2-dihydropyridine[79] | Trigonelline, ricinine, arecoline[77][80] |

| Polycyclic noncondensing pyridine derivatives | Nicotine, nornicotine, anabasine, anatabine[77][80] | ||

| Polycyclic condensed pyridine derivatives | Actinidine, gentianine, pediculinine[81] | ||

| Sesquiterpene pyridine derivatives | Nicotinic acid, isoleucine[21] | Evonine, hippocrateine, triptonine[78][79] | |

Isoquinoline derivatives and related alkaloids[82]

|

Simple derivatives of isoquinoline[83] | Tyrosine or phenylalanine → dopamine or tyramine (for alkaloids Amarillis)[84][85] | Salsoline, lophocerine[82][83] |

| Derivatives of 1- and 3-isoquinolines[86] | N-methylcoridaldine, noroxyhydrastinine[86] | ||

| Derivatives of 1- and 4-phenyltetrahydroisoquinolines[83] | Cryptostilin[83][87] | ||

| Derivatives of 5-naftil-isoquinoline[88] | Ancistrocladine[88] | ||

| Derivatives of 1- and 2-benzyl-izoquinolines[89] | Papaverine, laudanosine, sendaverine | ||

| Cularine group[90] | Cularine, yagonine[90] | ||

| Pavines and isopavines[91] | Argemonine, amurensine[91] | ||

| Benzopyrrocolines[92] | Cryptaustoline[83] | ||

| Protoberberines[83] | Berberine, canadine, ophiocarpine, mecambridine, corydaline[93] | ||

| Phthalidisoquinolines[83] | Hydrastine, narcotine (Noscapine)[94] | ||

| Spirobenzylisoquinolines[83] | Fumaricine[91] | ||

| Ipecacuanha alkaloids[95] | Emetine, protoemetine, ipecoside[95] | ||

| Benzophenanthridines[83] | Sanguinarine, oxynitidine, corynoloxine[96] | ||

| Aporphines[83] | Glaucine, coridine, liriodenine[97] | ||

| Proaporphines[83] | Pronuciferine, glaziovine[83][92] | ||

| Homoaporphines[98] | Kreysiginine, multifloramine[98] | ||

| Homoproaporphines[98] | Bulbocodine[90] | ||

| Morphines[99] | Morphine, codeine, thebaine, sinomenine,[100] heroin | ||

| Homomorphines[101] | Kreysiginine, androcymbine[99] | ||

| Tropoloisoquinolines[83] | Imerubrine[83] | ||

| Azofluoranthenes[83] | Rufescine, imeluteine[102] | ||

| Amaryllis alkaloids[103] | Lycorine, ambelline, tazettine, galantamine, montanine[104] | ||

| Erythrina alkaloids[87] | Erysodine, erythroidine[87] | ||

| Phenanthrene derivatives[83] | Atherosperminine[83][93] | ||

| Protopines[83] | Protopine, oxomuramine, corycavidine[96] | ||

| Aristolactam[83] | Doriflavin[83] | ||

Oxazole derivatives[105]

|

Tyrosine → tyramine[106] | Annuloline, halfordinol, texaline, texamine[107] | |

Isoxazole derivatives

|

Ibotenic acid → Muscimol | Ibotenic acid, Muscimol | |

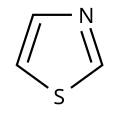

Thiazole derivatives[108]

|

1-Deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate (DOXP), tyrosine, cysteine[109] | Nostocyclamide, thiostreptone[108][110] | |

Quinazoline derivatives[111]

|

3,4-Dihydro-4-quinazolone derivatives | Anthranilic acid or phenylalanine or ornithine[112] | Febrifugine[113] |

| 1,4-Dihydro-4-quinazolone derivatives | Glycorine, arborine, glycosminine[113] | ||

| Pyrrolidine and piperidine quinazoline derivatives | Vazicine (peganine)[105] | ||

| Acridine derivatives[105]

|

Anthranilic acid[114] | Rutacridone, acronicine[115][116] | |

Quinoline derivatives[117][118]

|

Simple derivatives of quinoline derivatives of 2–quinolones and 4-quinolone | Anthranilic acid → 3-carboxyquinoline[119] | Cusparine, echinopsine, evocarpine[118][120][121] |

| Tricyclic terpenoids | Flindersine[118][122] | ||

| Furanoquinoline derivatives | Dictamnine, fagarine, skimmianine[118][123][124] | ||

| Quinines | Tryptophan → tryptamine → strictosidine (with secologanin) → korinanteal → cinhoninon[85][119] | Quinine, quinidine, cinchonine, cinhonidine[122] | |

Indole derivatives[100]

|

Non-isoprene indole alkaloids | ||

| Simple indole derivatives[125] | Tryptophan → tryptamine or 5-Hydroxytryptophan[126] | Serotonin, psilocybin, dimethyltryptamine (DMT), bufotenin[127][128] | |

| Simple derivatives of β-carboline[129] | Harman, harmine, harmaline, eleagnine[125] | ||

| Pyrroloindole alkaloids[130] | Physostigmine (eserine), etheramine, physovenine, eptastigmine[130] | ||

| Semiterpenoid indole alkaloids | |||

| Ergot alkaloids[100] | Tryptophan → chanoclavine → agroclavine → elimoclavine → paspalic acid → lysergic acid[130] | Ergotamine, ergobasine, ergosine[131] | |

| Monoterpenoid indole alkaloids | |||

| Corynanthe type alkaloids[126] | Tryptophan → tryptamine → strictosidine (with secologanin)[126] | Ajmalicine, sarpagine, vobasine, ajmaline, yohimbine, reserpine, mitragynine,[132][133] group strychnine and (Strychnine brucine, aquamicine, vomicine[134]) | |

| Iboga-type alkaloids[126] | Ibogamine, ibogaine, voacangine[126] | ||

| Aspidosperma-type alkaloids[126] | Vincamine, vinca alkaloids,[27][135] vincotine, aspidospermine[136][137] | ||

Imidazole derivatives[105]

|

Directly from histidine[138] | Histamine, pilocarpine, pilosine, stevensine[105][138] | |

Purine derivatives[139]

|

Xanthosine (formed in purine biosynthesis) → 7 methylxantosine → 7-methylxanthine → theobromine → caffeine[85] | Caffeine, theobromine, theophylline, saxitoxin[140][141] | |

| Alkaloids with nitrogen in the side chain (protoalkaloids) | |||

β-Phenylethylamine derivatives[92]

|

Tyrosine or phenylalanine → dioxyphenilalanine → dopamine → adrenaline and mescaline tyrosine → tyramine phenylalanine → 1-phenylpropane-1,2-dione → cathinone → ephedrine and pseudoephedrine[21][52][142] | Tyramine, ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, mescaline, cathinone, catecholamines (adrenaline, noradrenaline, dopamine)[21][143] | |

Colchicine alkaloids[144]

|

Tyrosine or phenylalanine → dopamine → autumnaline → colchicine[145] | Colchicine, colchamine[144] | |

Muscarine[146]

|

Glutamic acid → 3-ketoglutamic acid → muscarine (with pyruvic acid)[147] | Muscarine, allomuscarine, epimuscarine, epiallomuscarine[146] | |

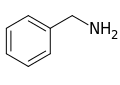

Benzylamine[148]

|

Phenylalanine with valine, leucine or isoleucine[149] | Capsaicin, dihydrocapsaicin, nordihydrocapsaicin, vanillylamine[148][150] | |

| Polyamines alkaloids | |||

| Putrescine derivatives[151]

|

ornithine → putrescine → spermidine → spermine[152] | Paucine[151] | |

| Spermidine derivatives[151]

|

Lunarine, codonocarpine[151] | ||

| Spermine derivatives[151]

|

Verbascenine, aphelandrine[151] | ||

| Peptide (cyclopeptide) alkaloids | |||

| Peptide alkaloids with a 13-membered cycle[48][153] | Nummularine C type | From different amino acids[48] | Nummularine C, Nummularine S[48] |

| Ziziphine type | Ziziphine A, sativanine H[48] | ||

| Peptide alkaloids with a 14-membered cycle[48][153] | Frangulanine type | Frangulanine, scutianine J[153] | |

| Scutianine A type | Scutianine A[48] | ||

| Integerrine type | Integerrine, discarine D[153] | ||

| Amphibine F type | Amphibine F, spinanine A[48] | ||

| Amfibine B type | Amphibine B, lotusine C[48] | ||

| Peptide alkaloids with a 15-membered cycle[153] | Mucronine A type | Mucronine A[45][153] | |

| Pseudoalkaloids (terpenes and steroids) | |||

Diterpenes[45]

|

Lycoctonine type | Mevalonic acid → Isopentenyl pyrophosphate → geranyl pyrophosphate[154][155] | Aconitine, delphinine[45][156] |

Steroidal alkaloids[157]

|

Cholesterol, arginine[158] | Solanidine, cyclopamine, batrachotoxin[159] | |

Properties

[edit]Most alkaloids contain oxygen in their molecular structure; those compounds are usually colorless crystals at ambient conditions. Oxygen-free alkaloids, such as nicotine[160] or coniine,[36] are typically volatile, colorless, oily liquids.[161] Some alkaloids are colored, like berberine (yellow) and sanguinarine (orange).[161]

Most alkaloids are weak bases, but some, such as theobromine and theophylline, are amphoteric.[162] Many alkaloids dissolve poorly in water but readily dissolve in organic solvents, such as diethyl ether, chloroform or 1,2-dichloroethane. Caffeine,[163] cocaine,[164] codeine[165] and nicotine[166] are slightly soluble in water (with a solubility of ≥1g/L), whereas others, including morphine[167] and yohimbine[168] are very slightly water-soluble (0.1–1 g/L). Alkaloids and acids form salts of various strengths. These salts are usually freely soluble in water and ethanol and poorly soluble in most organic solvents. Exceptions include scopolamine hydrobromide, which is soluble in organic solvents, and the water-soluble quinine sulfate.[161]

Most alkaloids have a bitter taste or are poisonous when ingested. Alkaloid production in plants appeared to have evolved in response to feeding by herbivorous animals; however, some animals have evolved the ability to detoxify alkaloids.[169] Some alkaloids can produce developmental defects in the offspring of animals that consume but cannot detoxify the alkaloids. One example is the alkaloid cyclopamine, produced in the leaves of corn lily. During the 1950s, up to 25% of lambs born by sheep that had grazed on corn lily had serious facial deformations. These ranged from deformed jaws to cyclopia. After decades of research, in the 1980s, the compound responsible for these deformities was identified as the alkaloid 11-deoxyjervine, later renamed to cyclopamine.[170]

Distribution in nature

[edit]

Alkaloids are generated by various living organisms, especially by higher plants – about 10 to 25% of those contain alkaloids.[171][172] Therefore, in the past the term "alkaloid" was associated with plants.[173]

The alkaloids content in plants is usually within a few percent and is inhomogeneous over the plant tissues. Depending on the type of plants, the maximum concentration is observed in the leaves (for example, black henbane), fruits or seeds (Strychnine tree), root (Rauvolfia serpentina) or bark (cinchona).[174] Furthermore, different tissues of the same plants may contain different alkaloids.[175]

Beside plants, alkaloids are found in certain types of fungus, such as psilocybin in the fruiting bodies of the genus Psilocybe, and in animals, such as bufotenin in the skin of some toads[24] and a number of insects, markedly ants.[176] Many marine organisms also contain alkaloids.[177] Some amines, such as adrenaline and serotonin, which play an important role in higher animals, are similar to alkaloids in their structure and biosynthesis and are sometimes called alkaloids.[178]

Extraction

[edit]

Because of the structural diversity of alkaloids, there is no single method of their extraction from natural raw materials.[179] Most methods exploit the property of most alkaloids to be soluble in organic solvents[4] but not in water, and the opposite tendency of their salts.

Most plants contain several alkaloids. Their mixture is extracted first and then individual alkaloids are separated.[180] Plants are thoroughly ground before extraction.[179][181] Most alkaloids are present in the raw plants in the form of salts of organic acids.[179] The extracted alkaloids may remain salts or change into bases.[180] Base extraction is achieved by processing the raw material with alkaline solutions and extracting the alkaloid bases with organic solvents, such as 1,2-dichloroethane, chloroform, diethyl ether or benzene. Then, the impurities are dissolved by weak acids; this converts alkaloid bases into salts that are washed away with water. If necessary, an aqueous solution of alkaloid salts is again made alkaline and treated with an organic solvent. The process is repeated until the desired purity is achieved.

In the acidic extraction, the raw plant material is processed by a weak acidic solution (e.g., acetic acid in water, ethanol, or methanol). A base is then added to convert alkaloids to basic forms that are extracted with organic solvent (if the extraction was performed with alcohol, it is removed first, and the remainder is dissolved in water). The solution is purified as described above.[179][182]

Alkaloids are separated from their mixture using their different solubility in certain solvents and different reactivity with certain reagents or by distillation.[183]

A number of alkaloids are identified from insects, among which the fire ant venom alkaloids known as solenopsins have received greater attention from researchers.[184] These insect alkaloids can be efficiently extracted by solvent immersion of live fire ants[4] or by centrifugation of live ants[185] followed by silica-gel chromatography purification.[186] Tracking and dosing the extracted solenopsin ant alkaloids has been described as possible based on their absorbance peak around 232 nanometers.[187]

Biosynthesis

[edit]Biological precursors of most alkaloids are amino acids, such as ornithine, lysine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan, histidine, aspartic acid, and anthranilic acid.[188] Nicotinic acid can be synthesized from tryptophan or aspartic acid. Ways of alkaloid biosynthesis are too numerous and cannot be easily classified.[85] However, there are a few typical reactions involved in the biosynthesis of various classes of alkaloids, including synthesis of Schiff bases and Mannich reaction.[188]

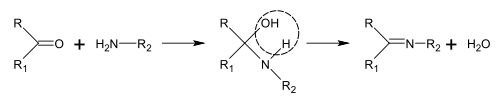

Synthesis of Schiff bases

[edit]Schiff bases can be obtained by reacting amines with ketones or aldehydes.[189] These reactions are a common method of producing C=N bonds.[190]

In the biosynthesis of alkaloids, such reactions may take place within a molecule,[188] such as in the synthesis of piperidine:[41]

Mannich reaction

[edit]An integral component of the Mannich reaction, in addition to an amine and a carbonyl compound, is a carbanion, which plays the role of the nucleophile in the nucleophilic addition to the ion formed by the reaction of the amine and the carbonyl.[190]

The Mannich reaction can proceed both intermolecularly and intramolecularly:[191][192]

Dimer alkaloids

[edit]In addition to the described above monomeric alkaloids, there are also dimeric, and even trimeric and tetrameric alkaloids formed upon condensation of two, three, and four monomeric alkaloids. Dimeric alkaloids are usually formed from monomers of the same type through the following mechanisms:[193]

- Mannich reaction, resulting in, e.g., voacamine

- Michael reaction (villalstonine)

- Condensation of aldehydes with amines (toxiferine)

- Oxidative addition of phenols (dauricine, tubocurarine)

- Lactonization (carpaine).

There are also dimeric alkaloids formed from two distinct monomers, such as the vinca alkaloids vinblastine and vincristine,[27][135] which are formed from the coupling of catharanthine and vindoline.[194][195] The newer semi-synthetic chemotherapeutic agent vinorelbine is used in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer.[135][196] It is another derivative dimer of vindoline and catharanthine and is synthesised from anhydrovinblastine,[197] starting either from leurosine[198][199] or the monomers themselves.[135][195]

Biological role

[edit]Alkaloids are among the most important and best-known secondary metabolites, i.e. biogenic substances not directly involved in the normal growth, development, or reproduction of the organism. Instead, they generally mediate ecological interactions, which may produce a selective advantage for the organism by increasing its survivability or fecundity. In some cases their function, if any, remains unclear.[200] An early hypothesis, that alkaloids are the final products of nitrogen metabolism in plants, as urea and uric acid are in mammals, was refuted by the finding that their concentration fluctuates rather than steadily increasing.[14]

Most of the known functions of alkaloids are related to protection. For example, aporphine alkaloid liriodenine produced by the tulip tree protects it from parasitic mushrooms. In addition, the presence of alkaloids in the plant prevents insects and chordate animals from eating it. However, some animals are adapted to alkaloids and even use them in their own metabolism.[201] Such alkaloid-related substances as serotonin, dopamine and histamine are important neurotransmitters in animals. Alkaloids are also known to regulate plant growth.[202] One example of an organism that uses alkaloids for protection is the Utetheisa ornatrix, more commonly known as the ornate moth. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids render these larvae and adult moths unpalatable to many of their natural enemies like coccinelid beetles, green lacewings, insectivorous hemiptera and insectivorous bats.[203] Another example of alkaloids being utilized occurs in the poison hemlock moth (Agonopterix alstroemeriana). This moth feeds on its highly toxic and alkaloid-rich host plant poison hemlock (Conium maculatum) during its larval stage. A. alstroemeriana may benefit twofold from the toxicity of the naturally occurring alkaloids, both through the unpalatability of the species to predators and through the ability of A. alstroemeriana to recognize Conium maculatum as the correct location for oviposition.[204] A fire ant venom alkaloid known as solenopsin has been demonstrated to protect queens of invasive fire ants during the foundation of new nests, thus playing a central role in the spread of this pest ant species around the world.[205]

Applications

[edit]In medicine

[edit]Medical use of alkaloid-containing plants has a long history, and, thus, when the first alkaloids were isolated in the 19th century, they immediately found application in clinical practice.[206] Many alkaloids are still used in medicine, usually in the form of salts widely used including the following:[14][207]

Many synthetic and semisynthetic drugs are structural modifications of the alkaloids, which were designed to enhance or change the primary effect of the drug and reduce unwanted side-effects.[208] For example, naloxone, an opioid receptor antagonist, is a derivative of thebaine that is present in opium.[209]

In agriculture

[edit]Prior to the development of a wide range of relatively low-toxic synthetic pesticides, some alkaloids, such as salts of nicotine and anabasine, were used as insecticides. Their use was limited by their high toxicity to humans.[210]

Use as psychoactive drugs

[edit]Preparations of plants and fungi containing alkaloids and their extracts, and later pure alkaloids, have long been used as psychoactive substances. Cocaine, caffeine, and cathinone are stimulants of the central nervous system.[211][212] Mescaline and many indole alkaloids (such as psilocybin, dimethyltryptamine and ibogaine) have hallucinogenic effect.[213][214] Morphine and codeine are strong narcotic pain killers.[215]

There are alkaloids that do not have strong psychoactive effect themselves, but are precursors for semi-synthetic psychoactive drugs. For example, ephedrine and pseudoephedrine are used to produce methcathinone and methamphetamine.[216] Thebaine is used in the synthesis of many painkillers such as oxycodone.

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Meissner, W. (1819). "Über Pflanzenalkalien: II. Über ein neues Pflanzenalkali (Alkaloid)" [About Plant Alkalis: II. About a New Plant Alkali (Alkaloid)]. Journal für Chemie und Physik. 25: 379–381. Archived from the original on 18 May 2023.

In the penultimate sentence of his article, Meissner wrote: "Überhaupt scheint es mir auch angemessen, die bis jetzt bekannten Pflanzenstoffe nicht mit dem Namen Alkalien, sondern Alkaloide zu belegen, da sie doch in manchen Eigenschaften von den Alkalien sehr abweichen, sie würden daher in dem Abschnitt der Pflanzenchemie vor den Pflanzensäuren ihre Stelle finden." ["In general, it seems appropriate to me to impose on the currently known plant substances not the name 'alkalis' but 'alkaloids', since they differ greatly in some properties from the alkalis; among the chapters of plant chemistry, they would therefore find their place before plant acids (since 'Alkaloid' would precede 'Säure' (acid) but follow 'Alkalien')".]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Luch, Andreas (2009). Molecular, Clinical and Environmental Toxicology, Volume 1: Molecular Toxicology. Vol. 1. Springer. p. 20. ISBN 9783764383367. OCLC 1056390214.

- ^ Lewis, Robert Alan (23 March 1998). Lewis' Dictionary of Toxicology. CRC Press. p. 51. ISBN 9781566702232. OCLC 1026521889.

- ^ Roberts, M. F. (Margaret F.); Wink, Michael (1998). Alkaloids: Biochemistry, Ecology, and Medicinal Applications. Boston: Springer US. ISBN 9781475729054. OCLC 851770197.

- ^ a b c Gonçalves Paterson Fox, Eduardo; Russ Solis, Daniel; Delazari dos Santos, Lucilene; Aparecido dos Santos Pinto, Jose Roberto; Ribeiro da Silva Menegasso, Anally; Cardoso Maciel Costa Silva, Rafael; Sergio Palma, Mario; Correa Bueno, Odair; de Alcântara Machado, Ednildo (April 2013). "A simple, rapid method for the extraction of whole fire ant venom (Insecta: Formicidae: Solenopsis)". Toxicon. 65: 5–8. Bibcode:2013Txcn...65....5G. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2012.12.009. hdl:11449/74946. PMID 23333648.

- ^ Kittakoop P, Mahidol C, Ruchirawat S (2014). "Alkaloids as important scaffolds in therapeutic drugs for the treatments of cancer, tuberculosis, and smoking cessation". Curr Top Med Chem. 14 (2): 239–252. doi:10.2174/1568026613666131216105049. PMID 24359196.

- ^ Russo P, Frustaci A, Del Bufalo A, Fini M, Cesario A (2013). "Multitarget drugs of plants origin acting on Alzheimer's disease". Curr Med Chem. 20 (13): 1686–93. doi:10.2174/0929867311320130008. PMID 23410167.

- ^ Raymond S. Sinatra; Jonathan S. Jahr; J. Michael Watkins-Pitchford (2010). The Essence of Analgesia and Analgesics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 82–90. ISBN 978-1139491983.

- ^ Cushnie TP, Cushnie B, Lamb AJ (2014). "Alkaloids: An overview of their antibacterial, antibiotic-enhancing and antivirulence activities". Int J Antimicrob Agents. 44 (5): 377–386. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.06.001. PMID 25130096. S2CID 205171789.

- ^ Singh, Sukhpal; Bansal, Abhishek; Singh, Vikramjeet; Chopra, Tanya; Poddar, Jit (June 2022). "Flavonoids, alkaloids and terpenoids: a new hope for the treatment of diabetes mellitus". Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders. 21 (1): 941–950. doi:10.1007/s40200-021-00943-8. ISSN 2251-6581. PMC 9167359. PMID 35673446.

- ^ a b Behl, Tapan; Gupta, Amit; Albratty, Mohammed; Najmi, Asim; Meraya, Abdulkarim M.; Alhazmi, Hassan A.; Anwer, Md. Khalid; Bhatia, Saurabh; Bungau, Simona Gabriela (9 September 2022). "Alkaloidal Phytoconstituents for Diabetes Management: Exploring the Unrevealed Potential". Molecules. 27 (18): 5851. doi:10.3390/molecules27185851. ISSN 1420-3049. PMC 9501853. PMID 36144587.

- ^ "Alkaloid". 18 December 2007.

- ^ Robbers JE, Speedie MK, Tyler VE (1996). "Chapter 9: Alkaloids". Pharmacognosy and Pharmacobiotechnology. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. pp. 143–185. ISBN 978-0683085006.

- ^ Rhoades, David F (1979). "Evolution of Plant Chemical Defense against Herbivores". In Rosenthal, Gerald A.; Janzen, Daniel H (eds.). Herbivores: Their Interaction with Secondary Plant Metabolites. New York: Academic Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-12-597180-5.

- ^ a b c Robert A. Meyers Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology – Alkaloids, 3rd edition. ISBN 0-12-227411-3

- ^ a b IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "alkaloids". doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00220

- ^ Manske, R. H. F. (12 May 2014). The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Physiology, Volume 8. Vol. 8. Saint Louis: Elsevier. pp. 683–695. ISBN 9781483222004. OCLC 1090491824.

- ^ a b c d "АЛКАЛОИДЫ - Химическая энциклопедия" [Alkaloids - Chemical Encyclopedia]. www.xumuk.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ^ Cseke, Leland J.; Kirakosyan, Ara; Kaufman, Peter B.; Warber, Sara; Duke, James A.; Brielmann, Harry L. (19 April 2016). Natural Products from Plants. CRC Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-4200-0447-2.

- ^ Johnson, Alyn William (1999). Invitation to Organic Chemistry. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-7637-0432-2.

- ^ Bansal, Raj K. (2003). A Textbook of Organic Chemistry. New Age International Limited. p. 644. ISBN 978-81-224-1459-2.

- ^ a b c d Aniszewski, p. 110

- ^ Hesse, pp. 1–3

- ^ Ladenburg, Albert (1882). Handwörterbuch der chemie (in German). E. Trewendt. pp. 213–422.

- ^ a b Hesse, p. 5

- ^ The suffix "ine" is a Greek feminine patronymic suffix and means "daughter of"; hence, for example, "atropine" means "daughter of Atropa" (belladonna): "Development of Systematic Names for the Simple Alkanes". yale.edu. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012.

- ^ Hesse, p. 7

- ^ a b c van der Heijden, Robert; Jacobs, Denise I.; Snoeijer, Wim; Hallard, Didier; Verpoorte, Robert (2004). "The Catharanthus alkaloids: Pharmacognosy and biotechnology". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 11 (5): 607–628. doi:10.2174/0929867043455846. PMID 15032608.

- ^ Cooper, Raymond; Deakin, Jeffrey John (2016). "Africa's gift to the world". Botanical Miracles: Chemistry of Plants That Changed the World. CRC Press. pp. 46–51. ISBN 9781498704304.

- ^ Raviña, Enrique (2011). "Vinca alkaloids". The evolution of drug discovery: From traditional medicines to modern drugs. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 157–159. ISBN 9783527326693.

- ^ a b Aniszewski, p. 182

- ^ Hesse, p. 338

- ^ Hesse, p. 304

- ^ Hesse, p. 350

- ^ Hesse, pp. 313–316

- ^ Begley, Natural Products in Plants.

- ^ a b Кониин in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian) – via Great Scientific Library

- ^ Hesse, p. 204

- ^ a b Hesse, p. 11

- ^ Orekhov, p. 6

- ^ Aniszewski, p. 109

- ^ a b Dewick, p. 307

- ^ Hesse, p. 12

- ^ a b Plemenkov, p. 223

- ^ Aniszewski, p. 108

- ^ a b c d Hesse, p. 84

- ^ a b Hesse, p. 31

- ^ a b c Dewick, p. 381

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Dimitris C. Gournelif; Gregory G. Laskarisb; Robert Verpoorte (1997). "Cyclopeptide alkaloids". Nat. Prod. Rep. 14 (1): 75–82. doi:10.1039/NP9971400075. PMID 9121730.

- ^ Aniszewski, p. 11

- ^ Plemenkov, p. 246

- ^ a b Aniszewski, p. 12

- ^ a b Dewick, p. 382

- ^ Hesse, pp. 44, 53

- ^ a b c Plemenkov, p. 224

- ^ a b c Aniszewski, p. 75

- ^ Orekhov, p. 33

- ^ a b c "Chemical Encyclopedia: Tropan alkaloids". xumuk.ru.

- ^ Hesse, p. 34

- ^ Aniszewski, p. 27

- ^ a b c d "Chemical Encyclopedia: Pyrrolizidine alkaloids". xumuk.ru.

- ^ Plemenkov, p. 229

- ^ Blankenship JD, Houseknecht JB, Pal S, Bush LP, Grossman RB, Schardl CL (2005). "Biosynthetic precursors of fungal pyrrolizidines, the loline alkaloids". ChemBioChem. 6 (6): 1016–1022. doi:10.1002/cbic.200400327. PMID 15861432. S2CID 13461396.

- ^ Faulkner JR, Hussaini SR, Blankenship JD, Pal S, Branan BM, Grossman RB, Schardl CL (2006). "On the sequence of bond formation in loline alkaloid biosynthesis". ChemBioChem. 7 (7): 1078–1088. doi:10.1002/cbic.200600066. PMID 16755627. S2CID 34409048.

- ^ Schardl CL, Grossman RB, Nagabhyru P, Faulkner JR, Mallik UP (2007). "Loline alkaloids: currencies of mutualism". Phytochemistry. 68 (7): 980–996. Bibcode:2007PChem..68..980S. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.01.010. PMID 17346759.

- ^ Plemenkov, p. 225

- ^ Aniszewski, p. 95

- ^ Orekhov, p. 80

- ^ a b c d e f "Chemical Encyclopedia: Quinolizidine alkaloids". xumuk.ru.

- ^ Saxton, Vol. 1, p. 93

- ^ Aniszewski, p. 98

- ^ Saxton, Vol. 1, p. 91

- ^ Joseph P. Michael (2002). "Indolizidine and quinolizidine alkaloids". Nat. Prod. Rep. 19 (5): 458–475. doi:10.1039/b208137g. PMID 14620842.

- ^ Saxton, Vol. 1, p. 92

- ^ Dewick, p. 310

- ^ Aniszewski, p. 96

- ^ Aniszewski, p. 97

- ^ a b c Plemenkov, p. 227

- ^ a b "Chemical Encyclopedia: pyridine alkaloids". xumuk.ru.

- ^ a b Aniszewski, p. 107

- ^ a b Aniszewski, p. 85

- ^ Plemenkov, p. 228

- ^ a b Hesse, p. 36

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "Chemical Encyclopedia: isoquinoline alkaloids". xumuk.ru.

- ^ Aniszewski, pp. 77–78

- ^ a b c d Begley, Alkaloid Biosynthesis

- ^ a b Saxton, Vol. 3, p. 122

- ^ a b c Hesse, p. 54

- ^ a b Hesse, p. 37

- ^ Hesse, p. 38

- ^ a b c Hesse, p. 46

- ^ a b c Hesse, p. 50

- ^ a b c Kenneth W. Bentley (1997). "β-Phenylethylamines and the isoquinoline alkaloids" (PDF). Nat. Prod. Rep. 14 (4): 387–411. doi:10.1039/NP9971400387. PMID 9281839. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b Hesse, p. 47

- ^ Hesse, p. 39

- ^ a b Hesse, p. 41

- ^ a b Hesse, p. 49

- ^ Hesse, p. 44

- ^ a b c Saxton, Vol. 3, p. 164

- ^ a b Hesse, p. 51

- ^ a b c Plemenkov, p. 236

- ^ Saxton, Vol. 3, p. 163

- ^ Saxton, Vol. 3, p. 168

- ^ Hesse, p. 52

- ^ Hesse, p. 53

- ^ a b c d e Plemenkov, p. 241

- ^ Brossi, Vol. 35, p. 261

- ^ Brossi, Vol. 35, pp. 260–263

- ^ a b Plemenkov, p. 242

- ^ Begley, Cofactor Biosynthesis

- ^ John R. Lewis (2000). "Amaryllidaceae, muscarine, imidazole, oxazole, thiazole and peptide alkaloids, and other miscellaneous alkaloids". Nat. Prod. Rep. 17 (1): 57–84. doi:10.1039/a809403i. PMID 10714899.

- ^ "Chemical Encyclopedia: Quinazoline alkaloids". xumuk.ru.

- ^ Aniszewski, p. 106

- ^ a b Aniszewski, p. 105

- ^ Richard B. Herbert; Herbert, Richard B.; Herbert, Richard B. (1999). "The biosynthesis of plant alkaloids and nitrogenous microbial metabolites". Nat. Prod. Rep. 16 (2): 199–208. doi:10.1039/a705734b.

- ^ Plemenkov, pp. 231, 246

- ^ Hesse, p. 58

- ^ Plemenkov, p. 231

- ^ a b c d "Chemical Encyclopedia: Quinoline alkaloids". xumuk.ru.

- ^ a b Aniszewski, p. 114

- ^ Orekhov, p. 205

- ^ Hesse, p. 55

- ^ a b Plemenkov, p. 232

- ^ Orekhov, p. 212

- ^ Aniszewski, p. 118

- ^ a b Aniszewski, p. 112

- ^ a b c d e f Aniszewski, p. 113

- ^ Hesse, p. 15

- ^ Saxton, Vol. 1, p. 467

- ^ Dewick, pp. 349–350

- ^ a b c Aniszewski, p. 119

- ^ Hesse, p. 29

- ^ Hesse, pp. 23–26

- ^ Saxton, Vol. 1, p. 169

- ^ Saxton, Vol. 5, p. 210

- ^ a b c d Keglevich, Péter; Hazai, Laszlo; Kalaus, György; Szántay, Csaba (2012). "Modifications on the basic skeletons of vinblastine and vincristine". Molecules. 17 (5): 5893–5914. doi:10.3390/molecules17055893. PMC 6268133. PMID 22609781.

- ^ Hesse, pp. 17–18

- ^ Dewick, p. 357

- ^ a b Aniszewski, p. 104

- ^ Hesse, p. 72

- ^ Hesse, p. 73

- ^ Dewick, p. 396

- ^ "PlantCyc Pathway: ephedrine biosynthesis". Archived from the original on 10 December 2011.

- ^ Hesse, p. 76

- ^ a b "Chemical Encyclopedia: colchicine alkaloids". xumuk.ru.

- ^ Aniszewski, p. 77

- ^ a b Hesse, p. 81

- ^ Brossi, Vol. 23, p. 376

- ^ a b Hesse, p. 77

- ^ Brossi, Vol. 23, p. 268

- ^ Brossi, Vol. 23, p. 231

- ^ a b c d e f Hesse, p. 82

- ^ "Spermine Biosynthesis". www.qmul.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 13 November 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f Plemenkov, p. 243

- ^ "Chemical Encyclopedia: Terpenes". xumuk.ru.

- ^ Begley, Natural Products: An Overview

- ^ Atta-ur-Rahman and M. Iqbal Choudhary (1997). "Diterpenoid and steroidal alkaloids". Nat. Prod. Rep. 14 (2): 191–203. doi:10.1039/np9971400191. PMID 9149410.

- ^ Hesse, p. 88

- ^ Dewick, p. 388

- ^ Plemenkov, p. 247

- ^ Никотин in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian) – via Great Scientific Library

- ^ a b c Grinkevich, p. 131

- ^ Spiller, Gene A. (23 April 2019). Caffeine. CRC Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-4200-5013-4.

- ^ "Caffeine". DrugBank. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Cocaine". DrugBank. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Codeine". DrugBank. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Nicotine". DrugBank. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Morphine". DrugBank. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ "Yohimbine". DrugBank. Archived from the original on 30 January 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ Fattorusso, p. 53

- ^ Thomas Acamovic; Colin S. Stewart; T. W. Pennycott (2004). Poisonous plants and related toxins, Volume 2001. CABI. p. 362. ISBN 978-0-85199-614-1.

- ^ Aniszewski, p. 13

- ^ Orekhov, p. 11

- ^ Hesse, p.4

- ^ Grinkevich, pp. 122–123

- ^ Orekhov, p. 12

- ^ Touchard, Axel; Aili, Samira; Fox, Eduardo; Escoubas, Pierre; Orivel, Jérôme; Nicholson, Graham; Dejean, Alain (20 January 2016). "The Biochemical Toxin Arsenal from Ant Venoms". Toxins. 8 (1): 30. doi:10.3390/toxins8010030. ISSN 2072-6651. PMC 4728552. PMID 26805882.

- ^ Fattorusso, p. XVII

- ^ Aniszewski, pp. 110–111

- ^ a b c d Hesse, p. 116

- ^ a b Grinkevich, p. 132

- ^ Grinkevich, p. 5

- ^ Grinkevich, pp. 132–134

- ^ Grinkevich, pp. 134–136

- ^ Fox, Eduardo Gonçalves Paterson (2016). "Venom Toxins of Fire Ants". In Gopalakrishnakone, P.; Calvete, Juan J. (eds.). Venom Genomics and Proteomics. Springer Netherlands. pp. 149–167. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6416-3_38. ISBN 978-94-007-6415-6.

- ^ Fox, Eduardo G. P.; Xu, Meng; Wang, Lei; Chen, Li; Lu, Yong-Yue (1 May 2018). "Speedy milking of fresh venom from aculeate hymenopterans". Toxicon. 146: 120–123. Bibcode:2018Txcn..146..120F. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2018.02.050. ISSN 0041-0101. PMID 29510162.

- ^ Chen, Jian; Cantrell, Charles L.; Shang, Han-wu; Rojas, Maria G. (22 April 2009). "Piperideine Alkaloids from the Poison Gland of the Red Imported Fire Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 57 (8): 3128–3133. doi:10.1021/jf803561y. ISSN 0021-8561. PMID 19326861.

- ^ Fox, Eduardo G. P.; Xu, Meng; Wang, Lei; Chen, Li; Lu, Yong-Yue (1 June 2018). "Gas-chromatography and UV-spectroscopy of Hymenoptera venoms obtained by trivial centrifugation". Data in Brief. 18: 992–998. Bibcode:2018DIB....18..992F. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2018.03.101. ISSN 2352-3409. PMC 5996826. PMID 29900266.

- ^ a b c Plemenkov, p. 253

- ^ Plemenkov, p. 254

- ^ a b Dewick, p. 19

- ^ Plemenkov, p. 255

- ^ Dewick, p. 305

- ^ Hesse, pp. 91–105

- ^ Hirata, K.; Miyamoto, K.; Miura, Y. (1994). "Catharanthus roseus L. (Periwinkle): Production of Vindoline and Catharanthine in Multiple Shoot Cultures". In Bajaj, Y. P. S. (ed.). Biotechnology in Agriculture and Forestry 26. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Vol. VI. Springer-Verlag. pp. 46–55. ISBN 9783540563914.

- ^ a b Gansäuer, Andreas; Justicia, José; Fan, Chun-An; Worgull, Dennis; Piestert, Frederik (2007). "Reductive C—C bond formation after epoxide opening via electron transfer". In Krische, Michael J. (ed.). Metal Catalyzed Reductive C—C Bond Formation: A Departure from Preformed Organometallic Reagents. Topics in Current Chemistry. Vol. 279. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 25–52. doi:10.1007/128_2007_130. ISBN 9783540728795.

- ^ Faller, Bryan A.; Pandi, Trailokya N. (2011). "Safety and efficacy of vinorelbine in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer". Clinical Medicine Insights: Oncology. 5: 131–144. doi:10.4137/CMO.S5074. PMC 3117629. PMID 21695100.

- ^ Ngo, Quoc Anh; Roussi, Fanny; Cormier, Anthony; Thoret, Sylviane; Knossow, Marcel; Guénard, Daniel; Guéritte, Françoise (2009). "Synthesis and biological evaluation of Vinca alkaloids and phomopsin hybrids". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 52 (1): 134–142. doi:10.1021/jm801064y. PMID 19072542.

- ^ Hardouin, Christophe; Doris, Eric; Rousseau, Bernard; Mioskowski, Charles (2002). "Concise synthesis of anhydrovinblastine from leurosine". Organic Letters. 4 (7): 1151–1153. doi:10.1021/ol025560c. PMID 11922805.

- ^ Morcillo, Sara P.; Miguel, Delia; Campaña, Araceli G.; Cienfuegos, Luis Álvarez de; Justicia, José; Cuerva, Juan M. (2014). "Recent applications of Cp2TiCl in natural product synthesis". Organic Chemistry Frontiers. 1 (1): 15–33. doi:10.1039/c3qo00024a. hdl:10481/47295.

- ^ Aniszewski, p. 142

- ^ Hesse, pp. 283–291

- ^ Aniszewski, pp. 142–143

- ^ W.E. Conner (2009). Tiger Moths and Woolly Bears—behaviour, ecology, and evolution of the Arctiidae. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–10. ISBN 0195327373.

- ^ Castells, Eva; Berenbaum, May R. (June 2006). "Laboratory Rearing of Agonopterix alstroemeriana, the Defoliating Poison Hemlock (Conium maculatum L.) Moth, and Effects of Piperidine Alkaloids on Preference and Performance". Environmental Entomology. 35 (3): 607–615. doi:10.1603/0046-225x-35.3.607. S2CID 45478867 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Fox, Eduardo G. P.; Wu, Xiaoqing; Wang, Lei; Chen, Li; Lu, Yong-Yue; Xu, Yijuan (1 February 2019). "Queen venom isosolenopsin A delivers rapid incapacitation of fire ant competitors". Toxicon. 158: 77–83. Bibcode:2019Txcn..158...77F. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2018.11.428. ISSN 0041-0101. PMID 30529381. S2CID 54481057.

- ^ Hesse, p. 303

- ^ Hesse, pp. 303–309

- ^ Hesse, p. 309

- ^ Dewick, p. 335

- ^ Matolcsy, G.; Nádasy, M.; Andriska, V. (1 January 1989). Pesticide Chemistry. Elsevier. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-08-087491-3.

- ^ Veselovskaya, p. 75

- ^ Hesse, p. 79

- ^ Veselovskaya, p. 136

- ^ Ibogaine: Proceedings from the First International Conference (The Alkaloids Book 56). Elsevier Science. 1950. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-12-469556-6.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Veselovskaya, p. 6

- ^ Veselovskaya, pp. 51–52

General and cited references

[edit]- Aniszewski, Tadeusz (2007). Alkaloids: secrets of life. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-52736-3.

- Begley, Tadhg P. (2009). Encyclopedia of Chemical Biology. Vol. 10. Wiley. pp. 1569–1570. doi:10.1002/cbic.200900262. ISBN 978-0-471-75477-0.

- Brossi, Arnold (1989). The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Pharmacology. Academic Press.

- Dewick, Paul M. (2002). Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach (Second ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-49640-3.

- Fattorusso, E.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O. (2008). Modern Alkaloids: Structure, Isolation, Synthesis and Biology. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-31521-5.

- Grinkevich NI; Safronich LN, eds. (1983). The chemical analysis of medicinal plants (in Russian). Moscow: Vysshaya Shkola.

- Hesse, Manfred (2002). Alkaloids: Nature's Curse or Blessing?. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-906390-24-6.

- Knunyants, IL (1988). Chemical Encyclopedia. Soviet Encyclopedia.

- Orekhov, AP (1955). Chemistry alkaloids (Acad. 2nd ed.). Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Plemenkov, VV (2001). Introduction to the Chemistry of Natural Compounds. Kazan.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Saxton, J. E. (1971). The Alkaloids: A Specialist Periodical Report. London: The Chemical Society.

- Veselovskaya, N. B.; Kovalenko, A. E. (2000). Drugs. Moscow: Triada-X.

- Wink, M (2009). "Mode of action and toxicology of plant toxins and poisonous plants". Mitt. Julius Kühn-Inst. 421: 93–112x.