Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Spindletop

View on Wikipedia

Spindle | |

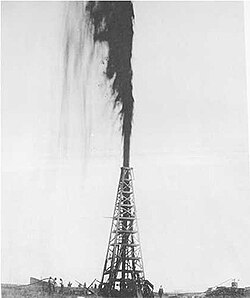

The Lucas gusher at Spindletop, January 10, 1901: This was the first major gusher of the Texas oil boom. | |

| Location | 3 mi south of Beaumont, Texas on Spindletop Ave. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 30°1′12″N 94°4′31″W / 30.02000°N 94.07528°W |

| Area | 1,130.4 acres (457.5 ha) |

| Built | 1901 |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000818[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 13, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | November 13, 1966 |

Spindletop is an oil field located in the southern portion of Beaumont, Texas, in the United States. The Spindletop dome was derived from the Louann Salt evaporite layer of the Jurassic geologic period.[2] On January 10, 1901, a well at Spindletop struck oil ("came in"). The Spindletop gusher blew for 9 days at a rate estimated at 100,000 barrels (16,000 m3) of oil per day.[3] Gulf Oil and Texaco, now part of Chevron Corporation, were formed to develop production at Spindletop.[4] The Spindletop discovery led the United States into the oil age. Prior to Spindletop, oil was primarily used for lighting and as a lubricant. Because of the quantity of oil discovered, burning petroleum as a fuel for mass consumption suddenly became economically feasible.

The frenzy of oil exploration and the economic development it generated in the state became known as the Texas oil boom. The United States soon became the world's leading oil producer.

History

[edit]Pattillo Higgins sought a source of natural gas for his brickyard and envisioned producing oil and gas from Sour Spring Mound, convinced it was an anticline. The eventual oil field would be called Spindletop, after a hill one mile to the east, and four miles south of Beaumont. The hill had the appearance of a spindle due to trees on its hilltop (cimas de boneteros, "tops of spindle-trees"). The mound was famous for its gas seeps, which Higgins lit for his Baptist Sunday school class. In August 1892, George W. O'Brien, George W. Carroll, Pattillo Higgins, and J.F. Lanier formed the Gladys City Oil, Gas, and Manufacturing Company to do exploratory drilling. The company tried drilling two test wells, but ran into trouble trying to penetrate below 300 feet (90 m), encountering a quicksand-like formation. Higgins quit the venture in 1896.[5][6][7]

Pattillo Higgins then teamed with Captain Anthony F. Lucas, the leading expert in the U.S. on salt-dome formations. Lucas made a lease agreement in 1899 with the Gladys City Company and a subsequent agreement with Higgins. Lucas drilled to 575 feet (180 m) before running out of money. He secured additional funding from John H. Galey, James M. Guffey, and Andrew Mellon of Pittsburgh, and the Guffey Petroleum Company was formed. Yet, the deal left Lucas with only an eighth share, and Higgins with nothing.[8][7]: 76–77, 147, 186 [5]: 29

Lucas and Galey employed the Hamill brothers for the drilling, while Galey picked the well site on land leased from the Beaumont Pasture Company. This tract of land was near the top of Sour Spring Mound. The well was spudded on 27 October 1900. At 160 feet (50 m), they hit the quicksands that had stopped earlier efforts. A solution consisted of driving an eight-inch casing pipe through the sand over the next 20 days, with a four-inch "wash pipe" to flush out the sand from the bottom of the hole with water. At around 250 feet (80 m), Lucas improvised a check valve to prevent the increased gas pressure from forcing sand into the casing, enabling them to reach a depth of 445 feet (140 m), and past the 285-foot (90 m) thick quicksand formation. At a depth of 645 feet (200 m), they adopted eighteen-hour shifts for continuous operations, drilling during the day, and keeping circulation going at night, to prevent a gas blowout. In early December, they hit a pocket of coarse water sand, when they adopted another innovation, mixing mud into the water which prevented the "heavier" water from dissipating into the sand. This drilling mud stabilized the hole, and soon they were drilling into a clay formation called gumbo. At 800 feet (240 m) they reached limestone, and on 9 December, oil started showing up in the slush pit. The oil was coming from a 35-foot (10 m) thick oil sand at a depth of 870 feet (270 m). Yet, that oil sand was too soft and fine to develop at that time, and Caroline Lucas convinced Galey to continue drilling to 1,200 feet (370 m), per contract. On Christmas Eve, they landed six-inch pipe below the sand at 880 feet (270 m), then enjoyed the holiday, returning New Year's Day. They hit another gas pocket, which forced water and mud out of the hole for ten minutes. Then, at 960 feet (290 m), they reached a sulphur layer, followed by more layers of limestone. On 10 January, they needed to replace the dull fishtail drill bit. While lowering the pipe down the hole, they only got to about 35 joints of pipe, or about 700 feet (210 m), before a low rumble sent mud, and then drill stem out of the hole. This was followed by silence, an explosion of more mud and gas, more silence, a flow of oil, and then a loud roar. On January 10, 1901, at a depth of 1,139 ft (347 m), what is known as the Lucas Gusher or the Lucas Geyser blew oil over 150 feet (50 m) in the air at a rate of 100,000 barrels per day (16,000 m3/d) (4,200,000 gallons). Nine days passed before the well was brought under control using a Christmas Tree devised by the Hamills.[3][7]: 78–81, 89, 93–110 [5]: 29–31

By late June, there were 13 gushers on Spindletop. These included those by David R. Beatty on 26 March, the Heywood Brothers Oil Company, two more from the J.M. Guffey Company, and the Higgins Oil and Fuel Company on 18 April.[7]: 129–132 Then in July 1901, the Hogg-Swayne Syndicate leased 15 acres from J.M. Guffey.[5]: 33

Spindletop was the largest gusher the world had seen and catapulted Beaumont into an oil-fueled boomtown. Beaumont's population of 10,000 tripled in 3 months and eventually rose to 50,000.[9] Speculation led land prices to increase rapidly. By the end of 1902, more than 500 companies had been formed and 285 wells were in operation.[3]

Spindletop produced 17,420,949 barrels of oil in 1902, but only half that much in 1903 as production declined. Yet Spindletop inspired wildcatting along the Gulf Coastal Plain. Significant salt dome oil fields included Sour Lake and Saratoga in 1902, Batson Prairie in 1903, the Humble oil field in 1905, and the Goose Creek Oil Field in 1908.[5]: 41–43 [7]: 159–160

Standard Oil, which then had a monopoly or near-monopoly on the petroleum industry in the eastern states, was prevented from moving aggressively into the new oilfield by state antitrust laws. Populist sentiment against Standard Oil was particularly strong at the time of the Spindletop discovery. In 1900, an oil-products marketing company affiliated with Standard Oil had been banned from the state for its cutthroat business practices. Although Standard built refineries in the area, it was unable to dominate the new Gulf Coast oil fields the way it had in the eastern states. As a result, a number of startup oil companies at Spindletop, such as Texaco and Gulf Oil, grew into formidable competitors to Standard Oil.[10]

Production at Spindletop began to decline rapidly after 1902, and the wells produced only 10,000 barrels per day (1,600 m3/d) by 1904.[3] Unfortunately the developers had signed a 20-year contract to sell 25,000 barrels per day at $0.25 per barrel to Shell Oil. When the price climbed above $0.35 per barrel, the operation was stressed and Mellon who had lent money for Spindle Top's development took control of the company, won a lawsuit allowing Mellon to renege on the contract, and in 1907, created Gulf Oil. On November 14, 1925, the Yount-Lee Oil Company brought in its McFaddin No. 2 at a depth around 2,500 feet (800 m), sparking a second boom, which culminated in the field's peak production year of 1927, during which 21 million barrels (3.3 GL) were produced.[3][5]: 128 Spindletop continued as a productive source of oil until about 1936. Stripper wells continue producing to this day. It was then mined for sulfur from the 1950s to about 1975.[11]

Spindletop-Gladys City Boomtown Museum

[edit]

In 1976, Lamar University dedicated the Spindletop-Gladys City Boomtown Museum to preserve the history of the Spindletop oil gusher era in Beaumont. The museum features an oil derrick and many reconstructed Gladys City building interiors furnished with authentic artifacts from the Spindletop boomtown period.[12]

The Lucas Gusher Monument is located at the museum. The monument, erected at the wellhead in July, 1941, was moved to the Spindletop-Gladys City Museum after it became unstable due to ground subsidence. According to an article by Nedra Foster, LS in the July/August, 2000 issue of the Professional Surveyor Magazine, the monument was originally located within 4 ft of the site of the Spindletop well.[13]

Today, the wellhead is marked at Spindletop Park by a flagpole flying the Texas flag. It is located about 1.5 miles south of the museum, off West Port Arthur Road/Spur 93. The site includes a viewing platform with information placards, about a quarter-mile from the flagpole. The wellhead site is in the middle of swampland on private land and is not accessible. Directions to the park and viewing platform are available at the museum.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013.

- ^ Hyne, Norman J., Nontechnical guide to petroleum geology, exploration, drilling, and production, Pennwell Books, 2nd ed. p. 193 ISBN 978-0-87814-823-3

- ^ a b c d e Wooster, Robert; Sanders, Christine Moor: Spindletop Oilfield from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 18, 2009., Texas State Historical Association

- ^ Daniel Yergin, The Prize, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991, pp. 75–78.

- ^ a b c d e f Olien, Diana; Olien, Roger (2002). Oil in Texas, The Gusher Age, 1895–1945. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 25–32. ISBN 0292760566.

- ^ Yergin, Daniel (1991). The Prize, The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 82–86. ISBN 978-0671799328.

- ^ a b c d e Linsley, Judith; Rienstrad, Ellen; Stiles, Jo (2002). Giant Under the Hill, A History of the Spindletop Oil Discovery at Beaumont, Texas in 1901. Austin: Texas State Historical Association. pp. 13–19, 23–52, 132. ISBN 978-0876112366.

- ^ Daniel Yergin, The Prize, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991, p. 75.

- ^ Daniel Yergin, The Prize, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991, p. 69.

- ^ Ron Chernow, Titan: the Life of John D. Rockefeller. New York: Random House, 1998). p. 431.

- ^ "Spindletop History". Lamar University. December 12, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2019.

- ^ "Spindletop Gladys City Boomtown Museum". Lamar.edu.

- ^ "Magazine Archives". xyHt. September 2024.

- McKinley, Fred B., and Greg Riley. Black Gold to Bluegrass: From the Oil Fields of Texas to Spindletop Farm of Kentucky, historical non-fiction, Austin: Eakin Press, 2005, ISBN 1-4241-7751-0

External links

[edit]- Spindletop-Gladys City Boomtown Museum

- Spindletop Oilfield from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Oil and Gas Industry from the Handbook of Texas Online

- "Spindletop: The Original Salt Dome", World Energy Magazine Vol. 3 No. 2