Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Boomtown

View on Wikipedia

A boomtown is a community that undergoes sudden and rapid population and economic growth, or that is started from scratch. The growth is normally attributed to the nearby discovery of a precious resource such as gold, silver, or oil, although the term can also be applied to communities growing very rapidly for different reasons, such as a proximity to a major metropolitan area, large infrastructure projects, or an attractive climate.

First boomtowns

[edit]

Early boomtowns, such as Leeds, Liverpool, and Manchester, experienced a dramatic surge in population and economic activity during the Industrial Revolution at the turn of the 19th century. In pre-industrial England these towns had been relative backwaters, compared to the more important market towns of Bristol, Norwich, and York, but they soon became major urban and industrial centres. Although these boomtowns did not directly owe their sudden growth to the discovery of a local natural resource, the factories were set up there to take advantage of the excellent Midlands infrastructure and the availability of large seams of cheap coal for fuel.[1]

Another typical boom town is Trieste in Italy. In the 19th century the free port and the opening of the Suez Canal began an extremely strong economic development. At the beginning of the First World War, the former fishing village with a deep-water port, which used to be small but geographically centrally located, was the third largest city of the Habsburg monarchy. Due to the many new borders, World War II and the Cold War, the city was completely isolated, abandoned and shrank for a long time. The handling of goods in the port and property prices fell sharply. Only when the surrounding countries joined the EU did Trieste return to the economic center of Europe.[2][3][4]

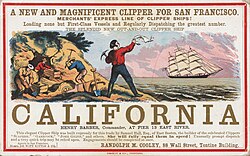

In the mid-19th century, boomtowns that were based on natural resources began to proliferate as companies and individuals discovered new mining prospects across the world. The California Gold Rush of the Western United States stimulated numerous boomtowns in that period, as settlements seemed to spring up overnight in the river valleys, mountains, and deserts around what was thought to be valuable gold mining country. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, boomtowns called mill towns would quickly arise due to sudden expansions in the timber industry; they tended to last the decade or so it took to clearcut nearby forests. Modern-day examples of resource-generated boomtowns include Fort McMurray in Canada, as the extraction of nearby oilsands requires a vast number of workers, and Johannesburg in South Africa, based on the gold and diamond trade.

Attributes

[edit]Boomtowns are typically characterized as "overnight expansions" in both population and money, as people stream into the community for mining prospects, high-paying jobs, attractive amenities or climate, or other opportunities. Typically, newcomers are drawn by high salaries or the prospect of "striking it rich" in mining; meanwhile, numerous indirect businesses develop to cater to workers often eager to spend their large paychecks. Often, boomtowns are the site of both economic prosperity and social disruption, as the local culture and infrastructure, if any, struggles to accommodate the waves of new residents. General problems associated with this fast growth can include: doctor shortages, inadequate medical and/or educational facilities, housing shortages, sewage disposal problems, and a lack of recreational activities for new residents.[5][6]

The University of Denver separates problems associated with a mining-specific boomtown into three categories:[5][7]

- deteriorating quality of life, as growth in basic industry outruns the local service sector's ability to provide housing, health services, schooling, and retail

- declining industrial productivity in mining because of labor turnover, labor shortages, and declining productivity

- an underserving by the local service sector in goods and services because capital investment in this sector does not build up adequately

The initial increasing population in Perth, Western Australia, Australia (considered to be a modern-day boomtown) gave rise to overcrowding of residential accommodation as well as squatter populations.[8] "The real future of Perth is not in Perth's hands but in Melbourne (and London) where Rio Tinto and BHP Billiton run their organizations", indicating that some boomtowns' growth and sustainability are controlled by an outside entity.[8]

Boomtowns are typically extremely dependent on the single activity or resource that is causing the boom (e.g., one or more nearby mines, mills, or resorts), and when the resources are depleted or the resource economy undergoes a "bust" (e.g., catastrophic resource price collapse), boomtowns can often decrease in size as fast as they initially grew. Sometimes, all or nearly the entire population can desert the town, resulting in a ghost town.

This can also take place on a planned basis. Since the late 20th century, mining companies have developed temporary communities to service a mine-site, building all the accommodation shops and services, using prefabricated housing or other buildings, making dormitories out of shipping containers, and removed all such structures as the resource was worked out.[citation needed]

Examples

[edit]Australia

[edit]

- Ararat (1850s Victorian Gold Rush)

- Ballarat (1850s–1880s Victorian Gold Rush)

- Bathurst (1850s Australian gold rushes)

- Bendigo (1850s–1880s Victorian Gold Rush)

- Broken Hill (1880s silver–lead–zinc boom)

- Castlemaine (1850s Victorian Gold Rush)

- Charters Towers (1870s gold rush)

- Gold Coast (1980s–2000s due to internal Australian migration trends)

- Kalgoorlie (1890s gold rush)

- Melbourne (1850s–1880s Victorian Gold Rush and associated speculative "land boom")

- Perth

Brazil

[edit]- Altamira, Pará

- Balsas, Maranhão

- Belém (Amazon rubber cycle)

- Brasília, Federal District, development of capital

- Goiânia, Goiás

- Laranjal do Jari, Amapá

- Luís Eduardo Magalhães, Bahia

- Manaus (Amazon rubber cycle)

- Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais (Ouro Preto Gold Rush)

- Palmas, Tocantins

- Parauapebas, Pará

- Rondonópolis, Mato Grosso

- Serra Pelada District, Curionópolis, Pará (Serra Pelada Gold Rush)

- Sinop, Mato Grosso

- Sorriso, Mato Grosso

- Tucuruí, Pará

- São Paulo, São Paulo

Canada

[edit]- Calgary, Alberta (during the 1970s oil boom in the province of Alberta)

- Barkerville, British Columbia

- Barrie, Ontario, residential development and factory retail outlets

- Brampton, Ontario, residential development and retail

- Dawson City, Yukon (Klondike Gold Rush)

- Edmonton, Alberta, railroad, cattle, residential development and retail

- Elliot Lake, Ontario

- Estevan, Saskatchewan

- Faro, Yukon

- Fisherville, British Columbia (gold rush boom town of 1864–1865)

- Fort McMurray, Alberta, oil extraction

- Greater Sudbury, Ontario

- Halifax, Nova Scotia, as a port city during the First World War, prior to The Halifax Explosion

- Kingston, Ontario, construction of Rideau Canal, penitentiary, post-secondary education, knowledge and services and residential development

- Kirkland Lake, Ontario

- Mississauga, Ontario, bedroom community and transportation (Toronto Pearson International Airport)

- Niagara Falls, Ontario, tourism, marriage conduction and tax-free retail

- Oil Springs, Ontario, oil drilling

- Ottawa, NCR, lumber/federal bureaucracy and high technology

- Petrolia, Ontario

- Sept-Îles, a city in the Côte-Nord region of eastern Québec, Canada

- Shawinigan, Quebec

- Sydney, Nova Scotia

- Vaughan, Ontario, residential development and retail

- Yellowknife, Northwest Territory, mining

United Kingdom

[edit]- Aberdeen, North Sea oil boom, known as the "oil capital of Europe"

- Barrow-in-Furness, late 19th and early 20th centuries as the world's largest steelworks and major shipyard

- Belfast, Northern Ireland, fastest-growing settlement in the British Isles in the 19th century due to industry and its port

- Consett,

- Jarrow,

- Leeds,

- Liverpool, industry and shipping, emigrants

- Manchester, rapid economic growth in the early 19th century

- Preston, Lancashire, the boomtown of the Industrial Revolution

- Winster, Derbyshire, England (17th century lead mining community)

United States

[edit]

- Anderson, Indiana, automotive industry

- Atlanta, Georgia (rapidly rebuilt and became a commercial center in the years following the Civil War)

- Atlantic City, New Jersey resort boomtown, 1870–1940

- Basic City, Virginia, railroads and mining, 1880s–1900s

- Beaumont, Texas, oil

- Belleville, California, gold-mining boomtown, 1860–1870

- Bentonville, Arkansas, corporate boomtown, 2010s–present

- Birmingham, Alabama, coal and iron ore, 1880s

- Blackwater, Missouri, railroads and mining, 1870–1940

- Bodie, California

- Borger, Texas

- Buffalo, New York, shipping via Erie Canal, steel production, 1825–1890

- Burkburnett, Texas

- Butte, Montana, copper and other resources

- Caldwell, Kansas

- Cement, California, 1902 1927

- Central City, Colorado

- Chester, Pennsylvania, shipbuilding and manufacturing during World Wars I and II

- Chicago, Illinois, railroads, commodity resources, business

- Cincinnati, Ohio, trade, shipping

- Colstrip, Montana

- Columbia, California

- Cripple Creek, Colorado

- Deadwood, South Dakota

- Denver, Colorado

- Detroit, Michigan rise of the automobile industry, 1910–1950

- Dodge City, Kansas

- El Paso, Texas

- Elkhart, Indiana recreational vehicle and manufactured housing industry

- Ellsworth, Kansas

- Endicott, New York (shoe manufacturing boomtown, 1900s–1920s)[9]

- Fairbanks, Alaska, during the Klondike Gold Rush and the building of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline

- Gary, Indiana, steel

- Gillette, Wyoming

- Goldfield, Nevada

- Graysonia, Arkansas

- Guthrie, Oklahoma, oil

- Hancock, Michigan

- Harrisburg, Illinois

- Holyoke, Massachusetts, paper, silk and wool textiles, 1860–1914

- Houghton, Michigan

- Humble, Texas

- Idaho City, Idaho, gold rush, 1860s

- Jeffrey City, Wyoming

- Kilgore, Texas

- La Paz, Arizona, gold-mining boomtown, 1862–1864

- Leadville, Colorado

- Minneapolis, Minnesota Lumber Industry 1852–1880

- Newport, Wisconsin, sprang up because of a bridge expected to be built across the Wisconsin River there

- New Bedford, Massachusetts, whaling

- Nome, Alaska

- Odessa, Texas, oil

- Ontario, Oregon, cannabis industry, beginning in the late 2010s[10]

- Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, steel, trade

- Pocatello, Idaho, railroad, 1870s–1920s

- Richland, Washington

- Rochester, New York, starting in the 1820s, with the opening of the Erie Canal

- Sacramento, California

- St. Elmo, Colorado, gold and silver mining

- St. Joseph, Florida

- San Francisco, California, US settlement after winning Mexican War

- Salt Lake City, Utah

- San Luis, Arizona

- Seattle, Washington, became a prosperous port city during the Klondike Gold Rush in 1897 subsequently after its great fire which also brought in an influx of jobs and newcomers

- Sioux City, Iowa

- Sunland Park, New Mexico, cannabis industry, beginning in the early 2020s[10]

- Tombstone, Arizona

- Texarkana, TX/AR

- Virginia City, Nevada, silver-mining boomtown, 1860s

- Wenatchee, Washington and other towns in the area are currently undergoing massive electrical infrastructure growth to support bitcoin mining due to the cheap local electricity[11]

- Wentzville, Missouri

- Williston, North Dakota, oil

Others

[edit]- Batam, Indonesia, free trade

- Carbonia, Italy

- Dubai, UAE - due to economic policies favoring zero income taxes, regulation-free banking, tax incentives, free trade, real estate investment, pro-Western diplomacy (sanctuary for international navy ships to dock at ports).

- Dublin, Ireland - due to catering to genealogical tourism of Americans descended from emigrés from previous centuries

- Dunedin, New Zealand due to the 1860s Gold Rush

- Bangalore, India– due to outsourcing of call centers and the IT industry

- Hyderabad, India– due to outsourcing of call centers and the IT industry

- New Town, Kolkata– due to growth of IT industry

- Johannesburg, South Africa - Gold/silver/diamond rush

- Karachi, Pakistan - manufacturing

- Kimberley, South Africa, diamonds and gold

- Leipzig, Germany[12][13]

- Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico, industrialization due to metallurgic and brewing industries and their related supply chains

- Nizhnevartovsk, Russia, oil

- Novosibirsk, Russia, planned development as a scientific and industrial center; hosted evacuated population and industry during World War II

- Roubaix, France[14][15]

- Shenzhen, China

- Ullensaker, Norway

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Brooks, Ann; Haworth, Bryan (1993). Boom town Manchester 1800–1850. Manchester: Portico Library.

- ^ Triest und die neue Seidenstraße

- ^ Triest– ungelöstes Hafenproblem

- ^ "Die ÖBB und der Hafen Triest verstärken Zusammenarbeit" In: Wiener Zeitung 18.03.2019.

- ^ a b "No. 2, Controlling Boomtown Development". Case Studies on Energy Impacts. 1976.

- ^ "Boomtown Social Effects". Fossil Fuel Connections. Retrieved 2025-01-14.

- ^ Duff, Mary K.; Gilmore, John S. (1975). Boomtown Growth Management. The University of Denver Research Institute.

- ^ a b Weller, Richard (2009). Boomtown 2050.

- ^ Aswad, Ed; Meredith, Suzanne M. (2003). Endicott-Johnson. Charleston, SC: Arcadia. p. 43. ISBN 978-0738513065. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ a b Goodman, J. David (7 January 2024). "Marijuana Buyers From Texas Fuel a 'Little Amsterdam' in New Mexico". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 January 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ Roberts, Paul (March 2018). "This Is What Happens When Bitcoin Miners Take Over Your Town". Politico. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ "Boomtown Leipzig – Der neue Hype im Osten". ARTE Info. Archived from the original on 2015-08-26.

- ^ Immobilien, Dima (15 April 2016). "Boomtown Leipzig– Immobilienmarkt explodiert– Dima Immobilien". dima-immobilien.de. Archived from the original on 2018-05-10.

- ^ Strikwerda, Carl (1984). "Regionalism and Internationalism: The Working-Class Movement in the Nord and the Belgian Connection, 1871–1914". In Sweets, John F. (ed.). Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual Meeting of the Western Society for French History. Vol. 12. p. 221. hdl:2027/mdp.39015012965524. ISSN 0099-0329.

Contemporaries never tired of calling Roubaix an "American city," because of its raw, fast-growing character, or of referring to Roubaix and its sister cities of Lille and Tourcoing as the "French Manchester."

- ^ Clark, Peter (2009). European Cities and Towns: 400–2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0199562732. Archived from the original on October 4, 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-01.

Roubaix was another new town, originally a craft village, whose many textile mills attracted a population of 100,000 and generated massive social and environmental problems.

External links

[edit]Boom towns are usually established in 5–12 years

.jpg/250px-Kilgore_May_2016_16_(Main_Street).jpg)

.jpg/2000px-Kilgore_May_2016_16_(Main_Street).jpg)