Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Stifle joint

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

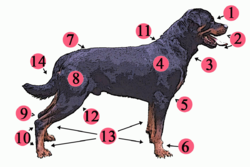

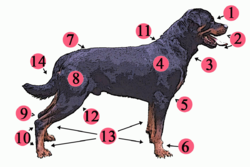

The stifle joint (often simply stifle) is a complex joint in the hind limbs of quadruped mammals such as the sheep, horse or dog. It is the equivalent of the human knee and is often the largest synovial joint in the animal's body. The stifle joint joins three bones: the femur, patella, and tibia. The joint consists of three smaller ones: the femoropatellar joint, medial femorotibial joint, and lateral femorotibial joint.[1]

The stifle joint consists of the femorotibial articulation (femoral and tibial condyles), femoropatellar articulation (femoral trochlea and the patella), and the proximal tibiofibular articulation.

The joint is stabilized by paired collateral ligaments which act to prevent abduction/adduction at the joint, as well as paired cruciate ligaments. The cranial cruciate ligament and the caudal cruciate ligament restrict cranial and caudal translation (respectively) of the tibia on the femur. The cranial cruciate also resists over-extension and inward rotation, and is the most commonly damaged stifle ligament in dogs.

"Cushioning" of the joint is provided by two C-shaped pieces of cartilage called menisci which sit between the medial and lateral condyles of the distal femur and the tibial plateau. The main biomechanical function of the menisci is probably to divide the joint into two functional units—the "femoromeniscal joint" for flexion/extension movements and the "meniscotibial joint" for rotation—a function analogous to that of the disc dividing the temporomandibular (jaw) joint. The menisci also contain nerve endings which are used to assist in proprioception.

The menisci are attached via a variety of ligaments: two meniscotibial ligaments for each meniscus, the meniscofemoral from the lateral meniscus to the femur, the meniscocollateral from the medial meniscus to the medial collateral ligament, and the transverse ligament (or intermeniscal) which runs between the two menisci.

There are between one and four sesamoid bones associated with the stifle joint in different species. These sesamoids assist with the smooth movement of tendon/muscle over the joint. The most well-known sesamoid bone is the patella, more commonly known as the "knee cap". It is located cranially to the joint and sits in the trochlear groove of the femur. It guides the patellar ligament of the quadriceps over the knee joint to its point of insertion on the tibia. Caudal to the joint, in the dog for example, are the two fabellae, which lie in the two tendons of origin of gastrocnemius. Fourth, there is often a small sesamoid bone in the tendon of origin of popliteus in many species. Humans possess only the patella.

In horses and oxen, the distal part of the tendon of insertion of quadriceps ("below" the patella) is divided into three parts. An elaborate twisting movement of the patella allows the stifle to "lock" in extension when the medial portion of the tendon is "hooked" over the bulbous medial trochlear ridge of the distal femur. This locking mechanism enables these animals to sleep while standing up.

References

[edit]- ^ Carpenter, D. H.; Cooper, R. C. (7 July 2008). "Mini Review of Canine Stifle Joint Anatomy". Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia. 29 (6): 321–329. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0264.2000.00289.x. ISSN 0340-2096.