Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Periosteum

View on Wikipedia| Periosteum | |

|---|---|

The periosteum covers the outside of bones. | |

| |

| Details | |

| Location | Outer surface of all bones |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | periosteum |

| MeSH | D010521 |

| TA98 | A02.0.00.007 |

| TA2 | 384 |

| TH | H2.00.03.7.00018 |

| FMA | 24041 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

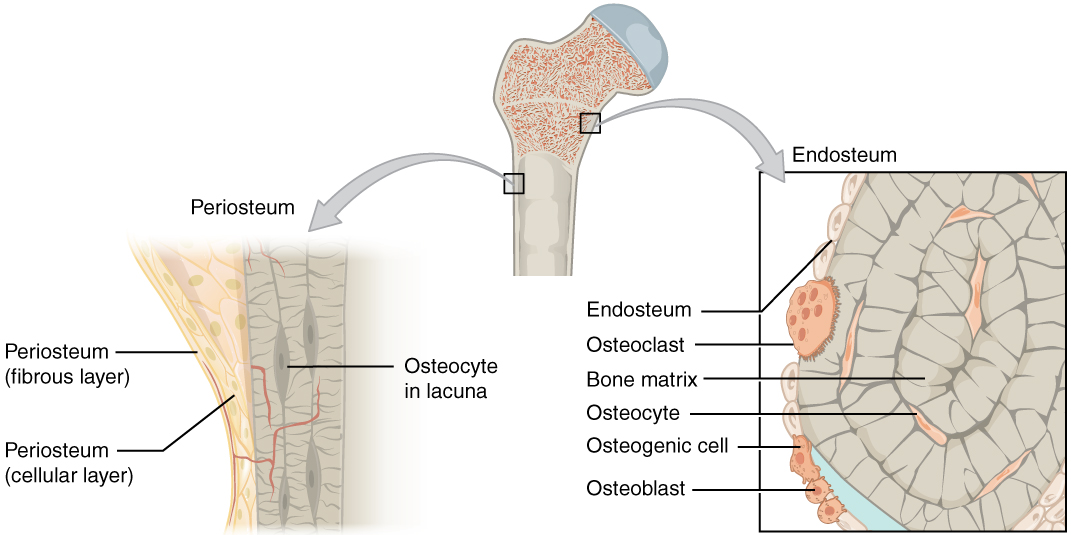

The periosteum is a membrane that covers the outer surface of all bones,[1] except at the articular surfaces (i.e. the parts within a joint space) of long bones. (At the joints of long bones the bone's outer surface is lined with "articular cartilage", a type of hyaline cartilage.) Endosteum lines the inner surface of the medullary cavity of all long bones.[2]

Structure

[edit]

The periosteum consists of an outer fibrous layer, and an inner cambium layer (or osteogenic layer). The fibrous layer is of dense irregular connective tissue, containing fibroblasts, while the cambium layer is highly cellular containing progenitor cells that develop into osteoblasts.[3] These osteoblasts are responsible for increasing the width of a long bone (the length of a long bone is controlled by the epiphyseal plate) and the overall size of the other bone types. After a bone fracture, the progenitor cells develop into osteoblasts and chondroblasts, which are essential to the healing process. The outer fibrous layer and the inner cambium layer are differentiated under electron micrography.[4]

As opposed to osseous tissue, the periosteum has nociceptors, sensory neurons that make it very sensitive to manipulation. It also provides nourishment by providing the blood supply to the body from the marrow.[5] The periosteum is attached to the bone by strong collagen fibres called "Sharpey's fibres", which extend to the outer circumferential and interstitial lamellae. It also provides an attachment for muscles and tendons.

The periosteum that covers the outer surface of the bones of the skull is known as the pericranium, except when in reference to the layers of the scalp.

Etymology

[edit]The word periosteum is derived from the Greek peri-, meaning "surrounding", and -osteon, meaning "bone". The peri refers to the fact that the periosteum is the outermost layer of long bones, surrounding other inner layers.[6]

Additional images

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Netter, Frank H; Crelin, Edmund S; Kaplan, Frederick S; Woodburne, Russell T; Regina, V.; Mankin, Henry J. (1987). Musculoskeletal System: A Compilation of Paintings of Anatomy, Physiology, and Metabolic Disorders, Part 1. Summit, New Jersey (NJ): CIBA-GEIGY Corporation. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-914168-14-0. OCLC 16943074.

- ^ "Definition of PERIOSTEUM". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2022-02-03.

- ^ Dwek, JR (April 2010). "The periosteum: what is it, where is it, and what mimics it in its absence?". Skeletal Radiology. 39 (4): 319–23. doi:10.1007/s00256-009-0849-9. PMC 2826636. PMID 20049593.

- ^ Nahian, Ahmed; Chauhan, Pradip R. (2021), "Histology, Periosteum And Endosteum", StatPearls, Treasure Island, Florida (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32491516, retrieved 2021-12-31

- ^ Modric, Jan (9 December 2013). "Periosteum Definition, Location, Anatomy, Histology and Function - eHealthStar". Retrieved 2022-02-03.

- ^ "peri- | Meaning of prefix peri- by etymonline". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 2022-02-03.

Further reading

[edit]- Brighton, Carl T.; Hunt, Robert M. (1997). "Early histologic and ultrastructural changes in microvessels of periosteal callus". Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma. 11 (4): 244–253. doi:10.1097/00005131-199705000-00002. PMID 9258821.

External links

[edit]- "Periosteum". Innerbody. Retrieved 2022-02-03.