Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Suger

View on Wikipedia

Suger (/suːˈʒɛər/;[2] French: [syʒɛʁ]; Latin: Sugerius; c. 1081 – 13 January 1151) was a French abbot and statesman. He was a key advisor to King Louis VI and his son Louis VII, acting as the latter's regent during the Second Crusade. His writings remain seminal texts for early twelfth-century Capetian history, and his reconstruction of the Basilica of Saint-Denis, where he was abbot, was instrumental in creating the Gothic architecture style.

Key Information

Early life

[edit]Suger was born into a family of minor knights c. 1081 (or 1080), landholders at Chennevières-lès-Louvres, a small village surrounding Saint-Denis in northern Parisis.[3] Suger was one of the younger sons in a family of some substance and upwardly connections where many went into the church, and so he was given as an oblate to the abbey of St. Denis at age ten in 1091. He first trained at the priory of Saint-Denis de L'Estrée for about a decade, where he would have first met the future king Louis VI of France.[note 1] Suger took up the oblate life relatively easily, and showed strong ability including in Latin and a firm grasp of legal matters. This ability led to him being chosen to work in the abbey archives to find documents that could protect the abbey from usurpation by Bouchard II of Montmorency, where historians speculate of his involvement in the appearance of a forged charter—if this was Suger's work, then it is certainly a fitting reflection and early example of his close admiration of the abbey.[note 2]

Suger began a successful career in monastic administration as he went on several missions for his abbey, which held land at several vantage points across the country. Finding favour with the abbot of Saint-Denis, Abbot Adam, Suger's political career would develop under him as in 1106 he became his secretary.[note 3] Suger found himself involved in significant events: in the same year, he was at the synod at Poitiers; in the Spring of 1107 to attend Pope Paschal II; in 1109, where he met Louis VI again as he sat a dispute between the king and Henry I of England, and; in 1112 at Rome for the second Lateran council. During this time, he held administrative roles that required him to be first at Berneval in Normandy in 1108 as provost, then from mid-1109 to 1111 provost to the more important priory of Toury. The area was suffering as a result of Hugh III of Le Puiset's exploitation of revenues, with a series of disputes and failing alliances eventually led to Suger gaining experience on the battlefield.[4] He appeared to take up this new challenge well and was successful, though would go on to heavily regret his involvement in warfare by his sixties.[5] There is a complete gap in sources on Suger's whereabouts after he left Toury in 1112,[6] though he was likely advancing his monastic position alongside working on further negotiations.

It is from 1118 when the sources start again, where Suger is deeply entrenched in royal affairs. He is chosen as the royal envoy to welcome the fleeing Pope Gelasius II (John of Gaetani) to France and arrange a meeting with Louis VI.[note 4] Suger was sent to live at the court of Gelasius at Maguelonne, and later at his successor Pope Calixtus II's court in Italy in 1121. It was on his return from in March 1122 that Suger, now 41, learned of Abbot Adam's death and that the others at the abbey had elected him to be the new abbot. Suger took pride in the fact that this happened in his absence and without his knowledge—whilst Louis was initially enraged at the fact that the decision was made without him being consulted first, he was clearly content with Suger assuming the role, as the two enjoyed a strong working relationship.

Court life and influence

[edit]Suger served as the friend and counsellor to both Louis VI and Louis VII. Until 1127, he occupied himself at court mainly with the temporal affairs of the kingdom, while during the following decade he devoted himself to the reorganization and reform of St-Denis.

Suger and Louis VI (1122–37)

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (April 2024) |

Suger and Louis VII (1137–49)

[edit]In 1137, he accompanied the future king, Louis VII, into Aquitaine on the occasion of that prince's marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine, and during the Second Crusade served as one of the regents of the kingdom (1147–1149). He bitterly opposed the king's divorce, having himself advised the marriage. Although he disapproved of the Second Crusade, he himself, at the time of his death, had started preaching a new crusade.

Suger, the Regent (1147–9)

[edit]Though Suger was openly against[7] Louis VII's intention announced in 1145 to lead a crusade to rescue the Kingdom of Jerusalem, a council in February 1147 elected Suger to be a regent.[note 5] One of the reasons Suger was opposed to the crusade were the issues present in France at the time: Louis VII wrote shortly after setting out to ensure protection of Gisors, and only six weeks after his expedition, asking for money, asking Suger to use some from his own resources if necessary.[note 6]

He urged the king to destroy the feudal bandits, was responsible for the royal tactics in dealing with the communal movements, and endeavoured to regularize the administration of justice. He left his abbey, which possessed considerable property, enriched and embellished by the construction of a new church built in the nascent Gothic style. Suger wrote extensively on the construction of the abbey in Liber de Rebus in Administratione sua Gestis, Libellus Alter de Consecratione Ecclesiae Sancti Dionysii, and Ordinatio.

Suger's final years (1149–51) and legacy

[edit]After the regency, Louis VII and his contemporaries still consulted Suger on matters ecclesiastical and political, and he was asked to defend in a number of cases at court. At this point, Suger was also being assigned cases to work on lone which would otherwise be given to an episcopal commission to deal with lone; Louis VII also gave to Suger the task of resolving two episcopal elections, at which point Suger practically continued to hold the same level of control over the church of France as he would have had as regent.[8] Following the failure of the Second Crusade and letters from the Jerusalem and Pope Eugenius, Suger proposed a new crusade at a convention in Laon in 1150, with the support of Louis and St Bernard. The aim was to have a crusade run by the French church to do what the secular powers failed to do, led by Suger.[9] Support for this fell apart from many churchmen, including the Pope losing belief in the pursuit and advising the king to remain in France to settle local issues. The matter troubled Suger to his final year of his life, at which point he nominated an (unnamed) nobleman to take his stead in battle, though it ultimately did not materialise as the idea was likely shelved by that point.[10]

Suger's final year continued to be busy for him, as he was instructed by the pope to reform Saint Corneille at Compiègne. Odo of Deuil's appointment as abbot had the backing of Louis VII and Suger, though after the two left, it was met with violent resistance by the canons (as was the case at Sainte-Geneviève).

-

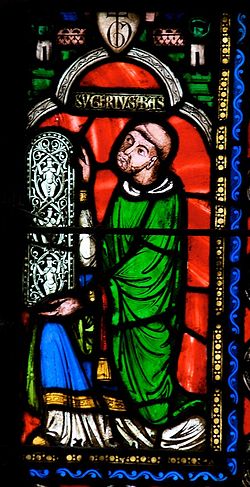

Suger in the Tree of Jesse window at St-Denis.

-

The Annunciation pane of the Infancy Window, showing Suger, the patron, at the feet of the Virgin.

-

A painting by Simon Vouet of Suger (1633), held at the Musée d'Arts de Nantes.

-

A marble statue by Jean-Baptiste Stouf (1836). Today, it stands in front of the ruins of Saint-Bertin Abbey, Saint-Omer.[11]

Today, a French street is named after Suger, and two schools bear his name (Lycée Suger in Saint-Denis, and École secondaire Suger in Vaucresson).

Contribution to the arts

[edit]

Abbey of Saint-Denis

[edit]The Abbey of Saint-Denis was, even prior to Suger's abbacy, a significant site, with a long tradition of royal burials dating back to the sixth century. Thus, when Suger was appointed to be its abbot, the tie between monarchy and church became even closer. Ideas to renovate the small and aging abbey arose as early as 1124, when he began to take in funds for the project—but work on the full rebuild as did not begin until 1137. The idea of a full rebuild, and what it should look like, was less a single moment and more a gradual development over time, as his ideas developed further. Early ideas were sporadic and undeveloped, with Suger mostly preoccupied with state affairs. Ground was first broken in 1130 to rebuild the old nave, with ideas of importing in classical columns from Rome, though this was an act rendered moot by the eventual decision for a full rebuild. The rebuild was not something Suger could have given much of his time to until the death of Louis VI and ascension of his son Louis VII, who wished to have his own set of advisors alongside his father's.

Suger began with the West front, reconstructing the original Carolingian façade with its single door. He designed the façade of Saint-Denis to be an echo of the Roman Arch of Constantine with its three-part division and three large portals to ease the problem of congestion. The rose window above the West portal is the earliest-known such example, although Romanesque circular windows preceded it in general form.[citation needed]

At the completion of the west front in 1140, Abbot Suger moved on to the reconstruction of the eastern end, leaving the Carolingian nave in use. He designed a choir (chancel) that would be suffused with light.[note 7][note 8] To achieve his aims, his masons drew on the several new features which evolved or had been introduced to Romanesque architecture, the pointed arch, the ribbed vault, the ambulatory with radiating chapels, the clustered columns supporting ribs springing in different directions and the flying buttresses which enabled the insertion of large clerestory windows.[citation needed]

The new structure was finished and dedicated on 11 June 1144,[12] in the presence of the King. The Abbey of Saint-Denis thus became the prototype for further building in the royal domain of northern France. It is often cited as the first building in the Gothic style. A hundred years later, the old nave of Saint-Denis was rebuilt in the Gothic style, gaining, in its transepts, two spectacular rose windows.[13]

Suger's collections

[edit]Suger was also a patron of art. Among the liturgical vessels he commissioned are a gilt eagle, the King Roger decanter, a gold chalice and a sardonyx ewer.[citation needed] A chalice once owned by Suger is now in the collections of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Eleanor of Aquitaine vase which he received that was subsequently offered to the saints at his abbey is now held in the Louvre in Paris, believed to be the only existing artefact of Eleanor's to exist today.

Historiography

[edit]Suger's writings

[edit]Suger wrote several works, which are regarded for their accuracy and detail. Of these, two record his activities as abbot of St-Denis. The Libellus Alter de Consecratione Ecclesiae Sancti Dionysii (Other Little Book on the Consecration of Saint-Denis) is a short treatise on the building and consecration of the abbey church.[14] The Liber De Rebus in Administratione sua Gestis (Book on Events under his Administration) is an unfinished account of his administration of the abbey, which he started on request of his monks in 1145.[15] In these texts, he treats of the improvements he had made to St Denis, describes the treasure of the church, and gives an account of the rebuilding. Unlike other medieval texts recording the deeds of religious figures, Suger’s are written by himself.[16]

Of his histories, Vie de Louis le Gros (Life of Louis the Fat) is his most substantial and widely circulated. It is a panegyric chronological narrative of king Louis VI, primarily concerned with warfare, but also his dependence on the Saint-Denis abbey.[17] Historia gloriosi regis Ludovici (The Illustrious King Louis) is the other demonstrably unfinished work of Suger, accounting for the first year of Louis VII’s reign.[18] Written in Suger’s final years, it (like his other history) covers in great detail events where Suger was himself present or involved in.

Suger’s secretary, William, himself produced two works on Suger: the first, a letter shortly after his death announcing the death; the other a short biography (Sugerii Vita; The Life of Suger) authored between summer 1152 and autumn 1154.[19][note 9] A collection of Suger’s letters exist in Saint Denis, mostly from near the end of his life, though its provenance is unknown.[20] Suger's works served to imbue the monks of St Denis with a taste for history and called forth a long series of quasi-official chronicles.[21]

Suger in the Gothic tradition

[edit]Suger is considered the forerunner of (French) Gothic architecture, where in its history he falls in the Early Gothic (Gothique primitif) period concentrated in the Île-de-France region of France. This new genre is seen as the progression of Romanesque architecture, though few of the key elements that define the Gothic tradition were particularly new as they were inspired by these very Romanesque elements, especially those of Normandy and Burgundy.[22] The key element that sets aside Gothic architecture from its predecessor is "the novelty of the spiritual message that was to be conveyed" using its "novel and anti-Romanesque" elements.[23]

Scholars tend to attribute Suger's influences on his ideas of symbolism and manner of symbolic thought to interpretations of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite and the derivates of John Scotus Eriugena, as well as; those from the school of Chartres.[note 10] Where Erwin Panofsky made the claim that this theology of Pseudo-Dionysius influenced the architectural style of the abbey of St. Denis, it was questioned by later scholars who have argued against such a simplistic link between philosophy and architectural form.[note 11] Though Suger did not leave any explicitly theological writings, his work on Saint Denis was inspired by his own set of religious ideas influenced by a range of new or renewed theological themes in the wider context of twelfth-century France. The influence of the cosmology of the Chartres school, which resulted from interpretations of Plato and the Bible, created a speculative system which emphasised mathematics, particularly geometry, and the aesthetic outcomes that arise from the convergence of the two.[24][note 12]

Art historians paint Gothic architecture as Suger's own creation, though some question this: Similarly the assumption by 19th century French authors that Suger was the "designer" of St Denis (and hence the "inventor" of Gothic architecture) has been almost entirely discounted by more recent scholars. Instead he is generally seen as having been a bold and imaginative patron who encouraged the work of an innovative (but now unknown) master mason.[25][26] It is difficult to contextualise St-Denis to other buildings of the time and place, due to the fact that many churches in Capetian France between 1080 and 1160 were destroyed and/or rebuilt later,[27] combined with the fact that no other building of this period enjoyed the level of precision and detail of Suger's accounts of St-Denis. Thus, the Gothic style can be seen as a multiplicity of trends in the architecture of this period, some occasionally intersecting with others: Jean Bony describes it as "a happy accident of history; it would have been infinitely more normal if the Gothic had never appeared."[28][29]

Citations

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Their friendship may have been shortlived for Louis had left the abbey's schooling in 1092: whilst it is not certain that the two were friends yet, it is not unlikely given the cozy number of students present. In 1124, Louis refers to Suger as a "faithful and familiar" companion (Jules Tardif, Monuments historiques, no. 391).

- ^ Lindy Grant, Abbot Suger of St-Denis: Church and State in Early Twelfth-Century France (Essex: Addison Wesley Longman, 1998) p. 80, fn. 30.

- ^ Suger has a tendency to downplay Abbot Adam's achievements: these are explored in Rolf Große, "L'abbé Adam, Prédécesseur De Suger," in Rolf Große, ed. Suger en question (Munich: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2004) pp. 31–43. [in French]

- ^ Pope Paschal II dies January 1118; John of Gaetani is made the new pope, becoming Gelasius II; Henry V marched on Rome and appointed Gregory (VIII) as an antipope; Gelasius fled to France to the protection of Louis VI.

- ^ Initially, Suger and William, count of Nevers were chosen in an election dominated by St Bernard, with the rationale as "twin swords—the ecclesiastical and securar—[to] protect the realm." William's imminent retirement as a monk meant that Ralph of Vermandois and, to a lesser degree, Archbishop Samson of Reims, to be co-regents with Suger. Grant, Church and State, 157.

- ^ "sive de nostro seu de vestro pecuniam sumptam nobis mittatis," [whether you send us money taken from us or from you,] in Recueil des Historiensdes Des Gaules et de la France, ed. Martin Bouquet et al. (Paris, 1869–1904) vol 15, p. 487.

- ^ When the new rear part is joined to that in front,

The church shines, brightened in its middle.

For bright is that which is brightly coupled with the bright

And which the new light pervades,

Bright is the noble work Enlarged in our time

I, who was Suger, having been leader

While it was accomplished.

Abbot Suger: On What Was Done in His Administration c.1144–8, Chap XXVIII - ^ Erwin Panofsky argued that Suger was inspired to create a physical representation of the Heavenly Jerusalem, however the extent to which Suger had any aims higher than aesthetic pleasure has been called into doubt by more recent art historians on the basis of Suger's own writings.

- ^ After Suger’s death, William’s leading of a faction against the new abbot at Saint Denis, Odo of Deuil, meant he was exiled. It was during exile that he authored the life of Suger; it was thus intended to portray Suger in good light, implicitly criticising Odo. Grant, Church and State, 44.

- ^ There are three Dionysiuses who have been confused and interchanged throughout history: Dionysius the Areopagite, an Athenian first century judge and saint; Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, a Greek author of the fifth/sixth century who pseudepigraphically (falsely) identified as the former and wrote Christian theological and mystical works; and saint Dionysius of Paris, or Denis of Paris, after whom the abbey is named after.

- ^ For a summary of the 'arguments against' Panofsky's view, see Panofsky, Suger and St Denis, Peter Kidson, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 50, (1987), pp. 1–17.

- ^ Further reading: Neoplatonism and Christianity#Middle_Ages, and von Simson, The Gothic Cathedral, pp. 25–39.

References

[edit]- ^ Charles Higounet, La Grange de Vaulerent (Paris: S. E. V. P. E. N., 1965) p. 11. This is a history of the Vaulerent barn and its development, from which we learn that the land had previously belonged to the Suger de Chennevières family.

- ^ "Suger". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ John F. Benton, "Suger's Life and Personality," in Paula Lieber Gerson, ed. Symposium (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986) p. 3.

- ^ John France, Medieval France at War (Leeds: Arc Humanities Press, 2022) p. 79. OCLC WorldCat 1381142379.

- ^ In Ordinatio, he asks God to forgive "what I have done," and refers to himself as "clearly being an irreligious man." (trans. Panofsky, p. 123)

- ^ Grant, Suger: Church and State, p. 96.

- ^ Willelmus, Vita., 394.

- ^ Grant, Church and State, 278.

- ^ Grant, Church and State, 279.

- ^ Grant, Church and State, 280.

- ^ When it was decided in 1931 that the statues be moved to the birth places of their representatives, Suger's was moved to Saint-Omer from a local legend that he was born there. "Statue de l'abbé Suger". Saint Omer tourism office. Archived from the original on 12 June 2024.

- ^ Honour, H. and J. Fleming, (2009) A World History of Art. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing, p. 376. ISBN 9781856695848

- ^ Wim Swaan, The Gothic Cathedral

- ^ Suger, Consc.

- ^ Suger, Admin., 155.

- ^ H. E. J. Cowdrey, The Age of Abbot Desiderius (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983) 13–6.

- ^ Suger, VLG.

- ^ Suger, Hist. VII.

- ^ Willelmus, Vita.

- ^ Grant, Church and State, 43–5.

- ^ Anne D. Hedeman, The Royal Image: Illustrations of the Grandes Chroniques de France, 1274-1422 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991) 3–6, 10.

- ^ Otto von Simson, The Gothic Cathedral: Origins of Gothic Architecture and the Medieval Concept of Order, 3rd ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988) 62.

- ^ von Simson, The Gothic Cathedral, 62.

- ^ von Simson, The Gothic Cathedral, pp. 26–7.

- ^ Conrad Rudolph, Artistic Change at St Denis: Abbot Suger's Program and the Early Twelfth Century Controversy Over Art, Princeton University Press, 1990

- ^ Kibler et al (eds) Medieval France: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, 1995

- ^ Take St-Meglorie, Ste-Genevie, and St-Victor in local Paris.

- ^ "[U]n hasard heureux de l'histoire. Il aurait été infiniment plus normal que le Gothique n'eût jamais paru," p. 11. Jean Bony, "Architecture gothique. Accident ou nécessité?" in Revuew de l'Art, LVIII-LVIX (1983) pp. 9–20.

- ^ Stephen Gardner, "L'église Saint-Julien de Marolles-en-Brie et ses rapports avec l'architecture Parisienne de la génération de Saint-Denis," in Bull Mon 153 (1995) pp. 23–46.

Bibliography

[edit]Contemporary works

[edit]- Suger. "Liber de Rebus in Administratione sua Gestis." In Abbot Suger, on the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and Its Art Treasures. Edited, translated, and annotated by Erwin Panofsky (and Gerda Panofsky-Soergel). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1946, pp. 40–81.

- ———. "Libellus Alter de Consecratione Ecclesiae Sancti Dionysii." In Abbot Suger, on the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and Its Art Treasures. Edited, translated, and annotated by Erwin Panofsky (and Gerda Panofsky-Soergel). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1946, pp. 82–121.

- ———. "Ordinatio AD. MCXL vel MCXLI confirmata." In Abbot Suger, on the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and its Art Treasures. Edited, translated, and annotated by Erwin Panofsky (and Gerda Panofsky-Soergel). Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1946, pp. 122–37.

- ———. The Deeds of Louis the Fat. [Vie de Louis le Gros] Translated by Richard C. Cusimano and John Moorhead. Washington D. C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1992.

- ———. "The Illustrious King Louis [VII], Son of Louis [VI]." [Historia gloriosi regis Ludovici] In Selected Works of Abbot Suger of Saint Denis. Translated by Richard C. Cusimano and Eric Whitmore. Washington D. C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2018, pp. 127–83.

- William (Willelmus). "The Life of Suger." [Sugerii Vita] In Selected Works of Abbot Suger of Saint Denis. Translated by Richard C. Cusimano and Eric Whitmore. Washington D. C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2018, pp. 184–216.

- Oeuvres complètes de Suger; recueillies, annotées et publiées d'après les manuscrits. [complete Latin manuscripts, available at Gallica BNF

]. Edited by Albert Lecoy de La Marche. Paris, 1867.

]. Edited by Albert Lecoy de La Marche. Paris, 1867.

Books

[edit]- Aubert, Marcel. Suger. [in French] Paris: Fontenelle Collection (Figures monastiques), 1950. OCLC WorldCat 1746084 / 778897850.

- Cartellieri, Otto. Abt Suger von Saint-Denis. [in German] Berlin: Matthiesen Verlag, Lübeck/Kraus Reprint Ltd, 1898.

- Crosby, Sumner McKnight. The Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis, from its beginnings to the death of Suger, 475–1151. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987. OCLC WorldCat 12805708.

- ———. The Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis, in the Time of Abbot Suger (1122–1151). [open access

] New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1981. OCLC WorldCat 7197399.

] New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1981. OCLC WorldCat 7197399. - Grant, Lindy. Abbot Suger of St-Denis: Church and State in Early Twelfth-Century France. Essex: Addison Wesley Longman, 1998. OCLC WorldCat 37509848.

- Gerson, Paula Lieber, ed. Abbot Suger and Saint-Denis: a Symposium. [available at Met OCLC

] New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986.

] New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986. - Große, Rolf, ed. Suger en question. [in French, available at De Gruyter

] Munich: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2004.

] Munich: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2004. - Rudolph, Conrad. Artistic Change at St-Denis: Abbot Suger's Program and the Early Twelfth-Century Controversy over Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990. OCLC WorldCat 614916294.

- von Simson, Otto. The Gothic Cathedral: Origins of Gothic Architecture and the Medieval Concept of Order. 3rd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988. OCLC WorldCat 17476906.

Journal articles

[edit]- Hugenholtz, Frits, and Henk Teunis. "Suger's advice." Journal of Medieval History 12, no. 3 (1986), pp. 191–206. DOI: 10.1016/0304-4181(86)90031-X.

- Inglis, Erik. "Remembering and Forgetting Suger at Saint-Denis, 1151–1534: An Abbot’s Reputation between Memory and History." Gesta 54, no. 2 (September 2015), pp. 219–43. JSTOR.

- Kidson, Peter. "Panofsky, Suger and St Denis." Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 50 (1987), pp. 1–17. JSTOR.

- Rudolph, Conrad. "Inventing the Exegetical Stained-Glass Window: Suger, Hugh, and a New Elite Art." The Art Bulletin 93, no. 4 (December 2011), pp. 399–422. JSTOR.

Websites

[edit]- Hunt, Patrick. "Abbé Suger and a Medieval Theory of Light in Stained Glass: Lux, Lumen, Illumination". Philolog. Stanford University, January 26, 2006. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016.

- Stones, Alison. "Images of Medieval Art and Architecture – FRANCE: Abbey Of St. Denis". Medart. University of Pittsburgh. It is an image archive of a large number of different artworks at the abbey.