Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Athens

View on Wikipedia

Athens[a] is the capital and largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica region and is the southernmost capital on the European mainland. With its urban area's population numbering over 3.6 million, it is the eighth-largest urban area in the European Union (EU). The Municipality of Athens (also City of Athens), which constitutes a small administrative unit of the entire urban area, had a population of 643,452 in 2021,[4] within its official limits, and a land area of 38.96 km2 (15.04 sq mi).[7][8]

Key Information

Athens is one of the world's oldest cities, with its recorded history spanning over 3,400 years,[9] and its earliest human presence beginning somewhere between the 11th and 7th millennia BCE. According to Greek mythology the city was named after Athena, the ancient Greek goddess of wisdom, but modern scholars generally agree that the goddess took her name after the city.[10] Classical Athens was one of the most powerful city-states in ancient Greece. It was a centre for democracy, the arts, education and philosophy,[11][12] and was highly influential throughout the European continent, particularly in Ancient Rome.[13] For this reason it is often regarded as the cradle of Western civilisation and the birthplace of democracy in its own right independently from the rest of Greece.[14][15]

In modern times Athens is a large cosmopolitan metropolis and central to economic, financial, industrial, maritime, political and cultural life in Greece. It is a Beta (+) – status global city according to the Globalization and World Cities Research Network,[16] and is one of the biggest economic centres in Southeast Europe. It also has a large financial sector, and its port Piraeus is both the second-busiest passenger port in Europe[17] and the thirteenth-largest container port in the world.[18] The Athens metropolitan area[19] extends beyond its administrative municipal city limits as well as its urban agglomeration, with a population of 3,638,281 in 2021[4][20][21] over an area of 2,928.717 km2 (1,131 sq mi).[8]

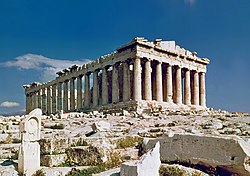

The heritage of the Classical Era is still evident in the city, represented by ancient monuments, and works of art, the most famous of all being the Parthenon, considered a key landmark of early Western culture. Athens retains Roman, Byzantine and a smaller number of Ottoman monuments, while its historical urban core features elements of continuity through its millennia of history. Athens contains two World Heritage Sites recognised by UNESCO: the Acropolis of Athens and the medieval Daphni Monastery. Athens is home to several museums and cultural institutions, such as the National Archeological Museum, featuring the world's largest collection of ancient Greek antiquities, the Acropolis Museum, the Museum of Cycladic Art, the Benaki Museum and the Byzantine and Christian Museum. Athens was the host city of the first modern-day Olympic Games in 1896, and 108 years later it hosted the 2004 Summer Olympics, making it one of five cities to have hosted the Summer Olympics on more than one occasion.[22]

Etymology and names

[edit]In Ancient Greek the name of the city was Ἀθῆναι (Athênai, pronounced [atʰɛ̂ːnai̯] in Classical Attic), which is a plural word. In earlier Greek, such as Homeric Greek, the name had been current in the singular form though, as Ἀθήνη (Athḗnē).[23] It was possibly rendered in the plural later on, like those of Θῆβαι (Thêbai) and Μυκῆναι (Μukênai). The root of the word is probably not of Greek or Indo-European origin,[24] and is possibly a remnant of the Pre-Greek substrate of Attica.[24]

In classical antiquity it was debated whether Athens took its name from its patron goddess Athena (Attic Ἀθηνᾶ, Athēnâ, Ionic Ἀθήνη, Athḗnē, and Doric Ἀθάνα, Athā́nā) or Athena took her name from the city.[25] Modern scholars now generally agree that the goddess takes her name from the city,[25] because the ending -ene is common in names of locations, but rare for personal names.[25]

According to the ancient Athenian founding myth, Athena, the goddess of wisdom and war, competed against Poseidon, the God of the Seas, for patronage of the yet-unnamed city;[26] they agreed that whoever gave the Athenians the better gift would become their patron[26] and appointed Cecrops, the king of Athens, as the judge.[26] According to the account given by Pseudo-Apollodorus, Poseidon struck the ground with his trident and a salt water spring welled up.[26] In an alternative version of the myth from Virgil's poem Georgics, Poseidon instead gave the Athenians the first horse.[26] In both versions, Athena offered the Athenians the first domesticated olive tree.[26][27]

Cecrops accepted this gift[26] and declared Athena the patron goddess of Athens.[26][27] Eight different etymologies, now commonly rejected, have been proposed since the 17th century. Christian Lobeck proposed as the root of the name the word ἄθος (áthos) or ἄνθος (ánthos) meaning "flower", to denote Athens as the "flowering city". Ludwig von Döderlein proposed the stem of the verb θάω, stem θη- (tháō, thē-, "to suck") to denote Athens as having fertile soil.[28]

Athenians were called cicada-wearers (Ancient Greek: Τεττιγοφόροι) because they used to wear pins of golden cicadas. A symbol of being autochthonous (earth-born), because the legendary founder of Athens, Erechtheus was an autochthon or of being musicians, because the cicada is a "musician" insect.[29] In classical literature the city was sometimes referred to as the City of the Violet Crown, first documented in Pindar's ἰοστέφανοι Ἀθᾶναι (iostéphanoi Athânai), or as τὸ κλεινὸν ἄστυ (tò kleinòn ásty, "the glorious city").

During the medieval period, the name of the city was rendered once again in the singular as Ἀθήνα. Variant names included Setines, Satine, and Astines, all derivations involving false splitting of prepositional phrases.[30] King Alphonse X of Castile gives the pseudo-etymology 'the one without death/ignorance'.[31][page needed] In Ottoman Turkish, it was called آتينا Ātīnā.[32] .

History

[edit]- Kingdom of Athens 1556 BC–1068 BC

- City-state of Athens 1068 BC–322 BC

- Hellenic League 338 BC–322 BC

- Kingdom of Macedonia 322 BC–200 BC

- Roman Republic 200 BC–27 BC

- Roman Empire 27 BC–395 AD

- Eastern Roman Empire 395–1205

- Duchy of Athens 1205–1458

- Ottoman Empire 1458–1822

- First Hellenic Republic 1822–1827

- Ottoman Empire 1827–1833

- Greece 1833–present

Antiquity

[edit]The oldest known human presence in Athens is the Cave of Schist, which has been dated to between the 11th and 7th millennia BC.[33] Athens has been continuously inhabited for at least 5,000 years (3000 BC).[34][35] By 1400 BC, the settlement had become an important centre of the Mycenaean civilisation, and the Acropolis was the site of a major Mycenaean fortress, whose remains can be recognised from sections of the characteristic Cyclopean walls.[36] Unlike other Mycenaean centres, such as Mycenae and Pylos, it is not known whether Athens suffered destruction in about 1200 BC, an event often attributed to a Dorian invasion, and the Athenians always maintained that they were pure Ionians with no Dorian element. However, Athens, like many other Bronze Age settlements, went into economic decline for around 150 years afterwards.[37] Iron Age burials, in the Kerameikos[38] and other locations, are often richly provided for and demonstrate that from 900 BC onwards Athens was one of the leading centres of trade and prosperity in the region.[39]

By the sixth century BC, widespread social unrest led to the reforms of Solon. These would pave the way for the eventual introduction of democracy by Cleisthenes in 508 BC. Athens had by this time become a significant naval power with a large fleet, and helped the rebellion of the Ionian cities against Persian rule. In the ensuing Greco-Persian Wars Athens, together with Sparta, led the coalition of Greek states that would eventually repel the Persians, defeating them decisively at Marathon under the leadership of Miltiades in 490 BC, and crucially at Salamis under the leadership of Themistocles in 480 BC. However, this did not prevent Athens from being captured and sacked twice by the Persians within one year, after a heroic but ultimately failed resistance at Thermopylae by Spartans and other Greeks led by King Leonidas,[40] after both Boeotia and Attica fell to the Persians.

The decades that followed became known as the Golden Age of Athenian democracy, during which time Athens became the leading city of Ancient Greece, with its cultural achievements laying the foundations for Western civilisation.[14][15] The playwrights Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides flourished in Athens during this time, as did the historians Herodotus and Thucydides, the physician Hippocrates, and the philosophers Socrates and Plato. Guided by Pericles, who promoted the arts and fostered democracy, Athens embarked on an ambitious building program that saw the construction of the Acropolis of Athens (including the Parthenon), as well as empire-building via the Delian League. Originally intended as an association of Greek city-states, which were led by Cimon, to continue the fight against the Persians, the league soon turned into a vehicle for Athens's own imperial ambitions. The resulting tensions brought about the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), in which Athens was defeated by its rival Sparta.[41]

Nonetheless the city reemerged soon as a major power in the Greek world, forming the Second Athenian League during the time of the Spartan and Theban hegemonies. By the mid-4th century BC the northern Greek kingdom of Macedon was becoming dominant in Greek affairs. In 338 BC the armies of Philip II and his son Alexander the Great defeated an alliance of some of the Greek city-states led by Athens and Thebes at the Battle of Chaeronea. After this defeat, Athens joined the Hellenic League under Philip and then Alexander. Later, under Rome, Athens was given the status of a free city because of its widely admired schools. In the second century AD, the Roman emperor Hadrian, himself an Athenian citizen,[42] ordered the construction of a library, a gymnasium, an aqueduct which is still in use, several temples and sanctuaries, a bridge and financed the completion of the Temple of Olympian Zeus.

In the early 4th century AD the Eastern Roman Empire began to be governed from Constantinople, and with the construction and expansion of the imperial city, many of Athens's works of art were taken by the emperors to adorn it. The Empire became Christianised, and the use of Latin declined in favour of exclusive use of Greek; in the Roman imperial period, both languages had been used. In the later Roman period, Athens was ruled by the emperors continuing until the 13th century, its citizens identifying themselves as citizens of the Roman Empire ("Rhomaioi"). The conversion of the empire from paganism to Christianity greatly affected Athens, resulting in reduced reverence for the city.[35] Ancient monuments such as the Parthenon, Erechtheion and the Hephaisteion (Theseion) were converted into churches. As the empire became increasingly anti-pagan, Athens became a provincial town and experienced fluctuating fortunes.

The city remained an important centre of learning, especially of Neoplatonism—with notable pupils including Gregory of Nazianzus, Basil of Caesarea and the Roman emperor Julian (r. 355–363)—and consequently a centre of paganism. Christian items do not appear in the archaeological record until the early 5th century.[43] The sack of the city by the Herules in 267 and by the Visigoths under their king Alaric I (r. 395–410) in 396, however, dealt a heavy blow to the city's fabric and fortunes, and Athens was henceforth confined to a small fortified area that embraced a fraction of the ancient city.[43] The emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565) banned the teaching of philosophy by pagans in 529,[44] an event whose impact on the city is much debated,[43] but is generally taken to mark the end of the ancient history of Athens. Athens was sacked by the Slavs in 582, but remained in imperial hands thereafter, as highlighted by the visit of the emperor Constans II (r. 641–668) in 662/3 and its inclusion in the Theme of Hellas.[43]

-

The ruins of the Temple of Olympian Zeus, conceived by the sons of Peisistratus

-

The Ancient Agora of Athens, a major commercial centre (agora) of ancient Athens

-

The Tower of the Winds in the Roman Agora, the second commercial centre of ancient Athens

-

The Odeon of Herodes Atticus built in AD 161 by Herodes Atticus

Middle Ages

[edit]

The city was threatened by Saracen raids in the 8th–9th centuries—in 896, Athens was raided and possibly occupied for a short period, an event which left some archaeological remains and elements of Arabic ornamentation in contemporary buildings[45]—but there is also evidence of a mosque existing in the city at the time.[43] In the great dispute over Byzantine Iconoclasm, Athens is commonly held to have supported the iconophile position, chiefly due to the role played by Empress Irene of Athens in the ending of the first period of Iconoclasm at the Second Council of Nicaea in 787.[43] A few years later, another Athenian, Theophano, became empress as the wife of Staurakios (r. 811–812).[43]

Invasion of the empire by the Turks after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, and the ensuing civil wars, largely passed the region by and Athens continued its provincial existence unharmed. When the Byzantine Empire was rescued by the resolute leadership of the three Komnenos emperors Alexios, John and Manuel, Attica and the rest of Greece prospered. Archaeological evidence tells us that the medieval town experienced a period of rapid and sustained growth, starting in the 11th century and continuing until the end of the 12th century.

The Agora (marketplace) had been deserted since late antiquity, began to be built over, and soon the town became an important centre for the production of soaps and dyes. The growth of the town attracted the Venetians, and various other traders who frequented the ports of the Aegean, to Athens. This interest in trade appears to have further increased the economic prosperity of the town[46] .

The 11th and 12th centuries were the Golden Age of Byzantine art in Athens. Almost all of the most important Middle Byzantine churches in and around Athens were built during these two centuries, and this reflects the growth of the town in general. This medieval prosperity did not last. In 1204, the Fourth Crusade conquered Athens and the city was not recovered from the Latins before it was taken by the Ottoman Turks. It did not become Greek in government again until the 19th century.

From 1204 until 1458, Athens was ruled by Latins in three separate periods, following the Crusades. The "Latins", or "Franks", were western Europeans and followers of the Latin Church brought to the Eastern Mediterranean during the Crusades. Along with rest of Byzantine Greece, Athens was part of the series of feudal fiefs, similar to the Crusader states established in Syria and on Cyprus after the First Crusade. This period is known as the Frankokratia.

Ottoman Athens

[edit]

The first Ottoman attack on Athens, which involved a short-lived occupation of the town, came in 1397, under the Ottoman generals Yaqub Pasha and Timurtash.[45] In 1458, Athens was captured by the Ottomans under the personal leadership of Sultan Mehmed II.[45] As the Ottoman Sultan rode into the city, he was greatly struck by the beauty of its ancient monuments and issued a firman (imperial edict) forbidding their looting or destruction, on pain of death. The Parthenon was converted into the main mosque of the city.[35]

Under Ottoman rule, Athens was denuded of any importance and its population severely declined, leaving it as a "small country town" (Franz Babinger).[45] From the early 17th century, Athens came under the jurisdiction of the Kizlar Agha, the chief black eunuch of the Sultan's harem. The city had originally been granted by Sultan Ahmed I (r. 1603–1617) to Basilica, one of his favourite concubines, who hailed from the city, in response of complaints of maladministration by the local governors. After her death, Athens came under the purview of the Kizlar Agha.[47]

The Turks began a practice of storing gunpowder and explosives in the Parthenon and Propylaea. In 1640, a lightning bolt struck the Propylaea, causing its destruction.[48] In 1687, during the Morean War, the Acropolis was besieged by the Venetians under Francesco Morosini, and the temple of Athena Nike was dismantled by the Ottomans to fortify the Parthenon. A shot fired during the bombardment of the Acropolis caused a powder magazine in the Parthenon to explode (26 September), and the building was severely damaged, giving it largely the appearance it has today. The Venetian occupation of Athens lasted for six months, and both the Venetians and the Ottomans participated in the looting of the Parthenon. One of its western pediments was removed, causing even more damage to the structure.[35][45] During the Venetian occupation, the two mosques of the city were converted into Catholic and Protestant churches, but on 9 April 1688 the Venetians abandoned Athens again to the Ottomans.[45]

Modern history

[edit]

In 1822 a Greek insurgency captured the city, but it fell to the Ottomans again in 1826 (though Acropolis held till June 1827). Again the ancient monuments suffered badly. The Ottoman forces remained in possession until March 1833, when they withdrew.

Following the Greek War of Independence and the establishment of the Greek Kingdom, Athens was chosen to replace Nafplio as the second capital of the newly independent Greek state in 1834, largely because of historical and sentimental reasons.[49] At the time, after the extensive destruction it had suffered during the war of independence, it was reduced to a town of about 4,000 people (less than half its earlier population) in a loose swarm of houses along the foot of the Acropolis. The first King of Greece, King Otto of Bavaria, commissioned the architects Stamatios Kleanthis and Eduard Schaubert to design a modern city plan fit for the capital of a state.

The first modern city plan consisted of a triangle defined by the Acropolis, the ancient cemetery of Kerameikos and the new palace of the Bavarian king (now housing the Greek Parliament), so as to highlight the continuity between modern and ancient Athens. Neoclassicism, the international style of this epoch, was the architectural style through which Bavarian, French and Greek architects such as Hansen, Klenze, Boulanger or Kaftantzoglou designed the first important public buildings of the new capital.

In 1896, Athens hosted the first modern Olympic Games. In the 1920s a number of Greek refugees, expelled from Asia Minor after the Greco-Turkish War and Population exchange between Greece and Turkey, swelled Athens's population. After World War II and the Civil War ended, Athen's population boomed in the 1950s and 1960s.

In the 1980s it became evident that smog from factories and an ever-increasing fleet of cars, as well as a lack of adequate free space due to congestion, had evolved into the city's most important challenge. A series of anti-pollution measures taken by the city's authorities in the 1990s, combined with a substantial improvement of the city's infrastructure (including the Attiki Odos motorway, the expansion of the Athens Metro, and the new Athens International Airport), considerably alleviated pollution and transformed Athens into a much more functional city. Athens hosted the 2004 Summer Olympics. Further urban improvements began in the 2020s along the coastal zone, including the Hellenikon Park development and the Faliro Delta upgrade, adding to the Stavros Niarchos Centre. The Hellenikon Park development will feature the Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Athens, the first integrated resort in continental Europe and the Riviera Tower.

Geography

[edit]

Athens sprawls across the central plain of Attica that is often referred to as the Athens Basin or the Attica Basin (Greek: Λεκανοπέδιο Αθηνών/Αττικής, romanised: Lekanopédio Athinón/Attikís). The basin is bounded by four large mountains: Mount Aigaleo to the west, Mount Parnitha to the north, Mount Pentelicus to the northeast and Mount Hymettus to the east.[50] Beyond Mount Aegaleo lies the Thriasian plain, which forms an extension of the central plain to the west. The Saronic Gulf lies to the southwest. Mount Parnitha is the tallest of the four mountains (1,413 m (4,636 ft)),[51] and has been declared a national park. The Athens urban area spreads over 50 kilometres (31 mi) from Agios Stefanos in the north to Varkiza in the south. The city is located in the north temperate zone, 38 degrees north of the equator.

Athens is built around a large number of hills. Lycabettus is one of the tallest hills of the city proper and provides a view of the entire Attica Basin. The meteorology of Athens is deemed to be one of the most complex in the world because its mountains cause a temperature inversion phenomenon which, along with the Greek government's difficulties controlling industrial pollution, was responsible for the air pollution problems the city has faced.[35] This issue is not unique to Athens; for instance, Los Angeles and Mexico City also suffer from similar atmospheric inversion problems.[35]

The Cephissus river, the Ilisos and the Eridanos stream are the historical rivers of Athens.

Environment

[edit]

By the late 1970s the pollution of Athens had become so destructive that according to the then Greek Minister of Culture, Constantine Trypanis, "...the carved details on the five the caryatids of the Erechtheum had seriously degenerated, while the face of the horseman on the Parthenon's west side was all but obliterated."[52] A series of measures taken by the authorities of the city throughout the 1990s resulted in the improvement of air quality; the appearance of smog (or nefos as the Athenians used to call it) has become less common.

Measures taken by the Greek authorities throughout the 1990s have improved the quality of air over the Attica Basin. Nevertheless, air pollution still remains an issue for Athens, particularly during the hottest summer days. In late June 2007,[53] the Attica region experienced a number of brush fires,[53] including a blaze that burned a significant portion of a large forested national park in Mount Parnitha,[54] considered critical to maintaining a better air quality in Athens all year round.[53] Damage to the park has led to worries over a stalling in the improvement of air quality in the city.[53]

The major waste management efforts undertaken in the last decade, particularly the plant built on the small island of Psytalia, have greatly improved water quality in the Saronic Gulf, and the coastal waters of Athens are now accessible again to swimmers.

Parks

[edit]

Parnitha National Park is punctuated by well-marked paths, gorges, springs, torrents and caves dotting the protected area. Hiking and mountain-biking in all four mountains are popular outdoor activities for residents of the city. The National Garden of Athens was completed in 1840 and is a green refuge of 15.5 hectares in the centre of the Greek capital. Located between the Parliament and Zappeion buildings, the latter of which maintains its own garden of seven hectares. Parts of the City Centre have been redeveloped under a masterplan called the Unification of Archeological Sites of Athens, which has also gathered funding from the EU to help enhance the project.[55][56]

The landmark Dionysiou Areopagitou Street has been pedestrianised, forming a scenic route. The route starts from the Temple of Olympian Zeus at Vasilissis Olgas Avenue, continues under the southern slopes of the Acropolis near Plaka, and finishes just beyond the Temple of Hephaestus in Thiseio. The route in its entirety provides visitors with views of the Parthenon and the Agora, the meeting point of ancient Athenians, away from the busy City Centre.

The hills of Athens also provide green space. Lycabettus, Philopappos hill and the area around it, including Pnyx and Ardettos hill, are planted with pines and other trees, with the character of a small forest rather than typical metropolitan parkland. Also to be found is the Pedion tou Areos (Field of Mars) of 27.7 hectares, near the National Archaeological Museum.[57]

Climate

[edit]

Athens has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa). The climate in Athens can be considered warmer than some cities that are similar or even less distant from the equator such as Seoul, Melbourne, Buenos Aires and Cape Town. According to the meteorological station near the city centre which is operated by the National Observatory of Athens, the downtown area has a simple mean annual temperature of 19.2 °C (66.6 °F) while parts of the urban agglomeration may reach up to 19.8 °C (67.6 °F), being affected by the urban heat island effect.[58]. Fog is rare in the city centre, but somewhat more frequent in areas to the east, close to Mt. Hymettus.[59] Advection fog can occur in spring, especially along the coastline.

The southern section of the Athens metropolitan area (i.e., Elliniko, Athens Riviera) lies in the transitional zone between Mediterranean (Csa) and hot semi-arid climate (BSh), with its port-city of Piraeus being the most extreme example, receiving just 331.9 millimetres (13.07 in) per year. The areas to the south generally see less extreme temperature variations as their climate is moderated by the Saronic gulf.[60] The northern part of the city (i.e., Kifissia), owing to its higher elevation, features moderately lower temperatures and slightly increased precipitation year-round. The generally dry climate of the Athens basin compared to the precipitation amounts seen in a typical Mediterranean climate is due to the rain shadow effect caused by the Pindus mountain range and the Dirfys and Parnitha mountains, substantially drying the westerly[61] and northerly[59] winds respectively.

Snowfall is not very common. It usually does not cause heavy disruption to daily life, in contrast to the northern parts of the city, where blizzards occur on a somewhat more regular basis. The most recent examples include the snowstorms of 16 February 2021[62] and 24 January 2022,[63] when the entire urban area was blanketed in snow, apart, in the second case, to many areas adjacent to Piraeus.

Athens may get particularly hot in the summer, owing partly to the strong urban heat island effect characterising the city.[64] In fact, Athens has been referred to as the hottest city in mainland Europe,[65] and is the first city in Europe to appoint a chief heat officer to deal with severe heat waves.[66] Temperatures of 47.5°C and over have been reported in several locations of the metropolitan area, including within the urban agglomeration. Metropolitan Athens was until 2021 the holder of the World Meteorological Organization record for the highest temperature ever recorded in Europe with 48.0 °C (118.4 °F) which was recorded in the areas of Elefsina and Tatoi on 10 July 1977.[67][68]

| Climate data for downtown Athens (1991–2020, extremes 1890–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.8 (73.0) |

25.3 (77.5) |

28.2 (82.8) |

32.2 (90.0) |

37.6 (99.7) |

44.8 (112.6) |

42.8 (109.0) |

43.9 (111.0) |

38.7 (101.7) |

36.5 (97.7) |

30.5 (86.9) |

23.1 (73.6) |

44.8 (112.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.3 (55.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

26.5 (79.7) |

31.6 (88.9) |

34.3 (93.7) |

34.3 (93.7) |

29.6 (85.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.7 (62.1) |

21.8 (71.2) |

26.6 (79.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.4 (84.9) |

25.0 (77.0) |

20.3 (68.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

11.6 (52.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.1 (44.8) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.3 (54.1) |

17.0 (62.6) |

21.6 (70.9) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

20.4 (68.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.7 (47.7) |

15.0 (59.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6.5 (20.3) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

1.7 (35.1) |

6.2 (43.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

16.0 (60.8) |

15.5 (59.9) |

8.9 (48.0) |

5.9 (42.6) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 55.6 (2.19) |

44.4 (1.75) |

45.6 (1.80) |

27.6 (1.09) |

20.7 (0.81) |

11.6 (0.46) |

10.7 (0.42) |

5.4 (0.21) |

25.8 (1.02) |

38.6 (1.52) |

70.8 (2.79) |

76.3 (3.00) |

433.1 (17.06) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72 | 70 | 66 | 60 | 56 | 50 | 42 | 47 | 57 | 66 | 72 | 73 | 61 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Source 1: Cosmos, scientific magazine of the National Observatory of Athens[69] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteoclub[70][71] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Neos Kosmos, downtown Athens 85 m a.s.l. | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.8 (73.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

31.2 (88.2) |

36.4 (97.5) |

41.2 (106.2) |

42.6 (108.7) |

42.8 (109.0) |

38.1 (100.6) |

32.6 (90.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

23.4 (74.1) |

42.8 (109.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 14.1 (57.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.6 (70.9) |

25.8 (78.4) |

31.1 (88.0) |

34.1 (93.4) |

33.6 (92.5) |

29.6 (85.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

19.8 (67.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

23.5 (74.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.3 (52.3) |

12.3 (54.1) |

14.4 (57.9) |

18.0 (64.4) |

22.1 (71.8) |

27.2 (81.0) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.0 (86.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

20.8 (69.4) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

20.2 (68.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 8.6 (47.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

14.3 (57.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.4 (79.5) |

22.6 (72.7) |

17.6 (63.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

16.9 (62.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −1.2 (29.8) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

5.2 (41.4) |

12.6 (54.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

19.6 (67.3) |

20.8 (69.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

9.3 (48.7) |

6.7 (44.1) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 52.1 (2.05) |

47.0 (1.85) |

31.9 (1.26) |

19.0 (0.75) |

17.0 (0.67) |

21.0 (0.83) |

5.9 (0.23) |

6.0 (0.24) |

21.2 (0.83) |

40.6 (1.60) |

60.0 (2.36) |

69.6 (2.74) |

391.3 (15.41) |

| Source 1: National Observatory of Athens Monthly Bulletins (Oct 2010 – Sep 2025) [72] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Neos Kosmos N.O.A station,[73] World Meteorological Organization[74] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Elliniko, coastal Athens (1955–2010), Extremes (1957–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.4 (72.3) |

24.2 (75.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

30.9 (87.6) |

35.6 (96.1) |

40.0 (104.0) |

42.2 (108.0) |

43.0 (109.4) |

37.2 (99.0) |

35.2 (95.4) |

28.6 (83.5) |

22.9 (73.2) |

43.0 (109.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.6 (56.5) |

14.1 (57.4) |

15.9 (60.6) |

19.6 (67.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

29.2 (84.6) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

15.1 (59.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.3 (50.5) |

10.6 (51.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.9 (69.6) |

25.6 (78.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.2 (82.8) |

24.3 (75.7) |

19.6 (67.3) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.9 (53.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

7.1 (44.8) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

20.3 (68.5) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

19.6 (67.3) |

15.7 (60.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.9 (26.8) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

0.6 (33.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

11.4 (52.5) |

15.5 (59.9) |

16.0 (60.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

3.0 (37.4) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 47.7 (1.88) |

38.5 (1.52) |

42.3 (1.67) |

25.5 (1.00) |

14.3 (0.56) |

5.4 (0.21) |

6.3 (0.25) |

6.2 (0.24) |

12.3 (0.48) |

45.9 (1.81) |

60.1 (2.37) |

62.0 (2.44) |

366.5 (14.43) |

| Average rainy days | 12.9 | 11.4 | 11.3 | 9.3 | 6.4 | 3.6 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 8.6 | 10.9 | 13.5 | 95.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69.3 | 68.0 | 65.9 | 62.2 | 58.2 | 51.8 | 46.6 | 46.8 | 54.0 | 62.6 | 69.2 | 70.4 | 60.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 130.2 | 134.4 | 182.9 | 231.0 | 291.4 | 336.0 | 362.7 | 341.0 | 276.0 | 207.7 | 153.0 | 127.1 | 2,773.4 |

| Source 1: HNMS (1955–2010 normals)[75] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (Extremes 1961–1990),[76] Info Climat (Extremes 1991–present)[77][78] | |||||||||||||

Administration

[edit]

Athens became the capital of Greece in 1834, following Nafplion, which was the provisional capital from 1829. The municipality (city) of Athens is also the capital of the Attica region. The term Athens can refer either to the municipality of Athens, to Greater Athens or urban area, or to the entire Athens Metropolitan Area.

The large city centre (Greek: Κέντρο της Αθήνας, romanised: Kéntro tis Athínas) of the Greek capital falls directly within the Municipality of Athens (Greek: Δήμος Αθηναίων, romanised: Dímos Athinaíon), which is the largest in population size in Greece and forms the core of the Athens urban area is made up of a series of smaller Municipal Communities, followed by the Municipality of Piraeus, which forms a significant city centre on its own within the Athens urban area and it is the second largest in population size within it.

Athens Urban Area

[edit]The Athens Urban Area (Greek: Πολεοδομικό Συγκρότημα Αθηνών, romanised: Poleodomikó Synkrótima Athinón), also known as Urban Area of the Capital (Greek: Πολεοδομικό Συγκρότημα Πρωτεύουσας, romanised: Poleodomikó Synkrótima Protévousas) or Greater Athens (Greek: Ευρύτερη Αθήνα, romanised: Evrýteri Athína),[79] today consists of 40 municipalities: 35 of them divided in four regional units (Central Athens, North Athens, West Athens, South Athens), and a further 5 municipalities which make up the regional unit of Piraeus. The Athens urban area spans over 412 km2 (159 sq mi),[80] with a population of 3,059,764 people as of 2021.

|

|

Athens metropolitan area

[edit]

The Athens metropolitan area spans 2,928.717 km2 (1,131 sq mi) within the Attica region and includes a total of 58 municipalities, which are organised in seven regional units (those outlined above, along with East Attica and West Attica), having reached a population of 3,638,281 according to the 2021 census.[4] Athens and Piraeus municipalities serve as the two metropolitan centres of the Athens Metropolitan Area.[81] There are also some inter-municipal centres serving specific areas. For example, Kifissia and Glyfada serve as inter-municipal centres for northern and southern suburbs respectively.

The Athens Metropolitan Area consists of 58[82] densely populated municipalities, sprawling around the Municipality of Athens (the City Centre) in virtually all directions. For the Athenians, all the urban municipalities surrounding the City Centre are called suburbs. According to their geographic location in relation to the City of Athens, the suburbs are divided into four zones; the northern suburbs (including Agios Stefanos, Dionysos, Ekali, Nea Erythraia, Kifissia, Kryoneri, Maroussi, Pefki, Lykovrysi, Metamorfosi, Nea Ionia, Nea Filadelfeia, Irakleio, Vrilissia, Melissia, Penteli, Chalandri, Agia Paraskevi, Gerakas, Pallini, Galatsi, Psychiko and Filothei); the southern suburbs (including Alimos, Nea Smyrni, Moschato, Tavros, Agios Ioannis Renti, Kallithea, Piraeus, Agios Dimitrios, Palaio Faliro, Elliniko, Glyfada, Lagonisi, Saronida, Argyroupoli, Ilioupoli, Varkiza, Voula, Vari and Vouliagmeni); the eastern suburbs (including Zografou, Dafni, Vyronas, Kaisariani, Cholargos and Papagou); and the western suburbs (including Peristeri, Ilion, Egaleo, Koridallos, Agia Varvara, Keratsini, Perama, Nikaia, Drapetsona, Chaidari, Petroupoli, Agioi Anargyroi, Ano Liosia, Aspropyrgos, Eleusina, Acharnes and Kamatero).

The Athens city coastline, extending from the major commercial port of Piraeus to the southernmost suburb of Varkiza for some 25 km (20 mi),[83] is also connected to the City Centre by tram.

In the northern suburb of Maroussi, the upgraded main Olympic Complex (known by its Greek acronym OAKA) dominates the skyline. The area has been redeveloped according to a design by the Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava, with steel arches, landscaped gardens, fountains, futuristic glass, and a landmark new blue glass roof which was added to the main stadium. A second Olympic complex, next to the sea at the beach of Palaio Faliro, also features modern stadia, shops and an elevated esplanade. Work is underway to transform the grounds of the old Athens Airport – named Elliniko – in the southern suburbs, into one of the largest landscaped parks in Europe, to be named the Hellenikon Metropolitan Park.[84]

Many of the southern suburbs (such as Alimos, Palaio Faliro, Elliniko, Glyfada, Voula, Vouliagmeni and Varkiza) known as the Athens Riviera, host a number of sandy beaches, most of which are operated by the Greek National Tourism Organisation and require an entrance fee. Casinos operate on both Mount Parnitha (Regency Casino Mont Parnes), some 25 km (16 mi)[85] from downtown Athens (accessible by car or cable car), and the nearby town of Loutraki (accessible by car via the Athens – Corinth National Highway, or the Athens Suburban Railway).

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]The concept of a partner city is used under different names in different countries, but they mean the same thing, that two cities in different countries assist each other as partners. Athens has quite a number of partners, whether as a "twin", a "sister", or a "partner."

Demographics

[edit]

The Municipality of Athens had a population of 643,452 people in 2021.[4] In the 2021 Population and Housing Census, the four regional units that make up the former Athens prefecture have a combined population of 2,611,713 . They, together with the regional unit of Piraeus (sometimes referred to as Greater Piraeus) make up the dense Athens Urban Area, or Greater Athens, which reaches a total population of 3,059,764 inhabitants (in 2021).[4]

The municipality (centre) of Athens is the most populous in Greece, with a population of 643,452 people (in 2021)[4] and an area of 38.96 km2 (15.04 sq mi),[7] forming the core of the Athens Urban Area within the Attica Basin. The incumbent Mayor of Athens is Charis Doukas of PASOK. The municipality is divided into seven municipal districts which are mainly used for administrative purposes.[86]

For the Athenians the most popular way of dividing the downtown is through its neighbourhoods such as Pagkrati, Ampelokipoi, Goudi, Exarcheia, Patisia, Ilisia, Petralona, Plaka, Anafiotika, Koukaki, Kolonaki and Kypseli, each with its own distinct history and characteristics.

Romani people are concentrated in Acharnes, Ano Liosia, Agia Varvara, Zefeiri and Kamatero.[87]

There is a large Albanian community in Athens.[88]

Metropolitan Area

[edit]The Athens Metropolitan Area, with an area of 2,928.717 km2 (1,131 sq mi) and inhabited by 3,744,059 people in 2021,[4] consists of the Athens Urban Area with the addition of the towns and villages of East and West Attica, which surround the dense urban area of the Greek capital. It actually sprawls over the whole peninsula of Attica, which is the best part of the region of Attica, excluding the islands.

| Classification of regional units within Greater Athens, Athens Urban Area and Athens Metropolitan Area | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional unit | Population (2021)[4] | Land Area (km2) | Area | ||

| Central Athens | 1,002,212 | 87.4 | Former Athens prefecture 2,611,713 364.2 km2 |

Athens Urban Area or Greater Athens 3,059,764 414.6 km2 |

Athens Metropolitan Area 3,744,059 2931.6 km2 |

| North Athens | 601,163 | 140.7 | |||

| South Athens | 529,455 | 69.4 | |||

| West Athens | 478,883 | 66.7 | |||

| Piraeus | 448,051 | 50.4 | Piraeus regional unit 448,051 50.4 km2 | ||

| East Attica | 518,755 | 1,513 | |||

| West Attica | 165,540 | 1,004 | |||

Safety

[edit]Athens ranks in the lowest percentage for the risk on frequency and severity of terrorist attacks according to the EU Global Terrorism Database (EIU 2007–2016 calculations). The city also ranked 35th in Digital Security, 21st on Health Security, 29th on Infrastructure Security and 41st on Personal Security globally in a 2017 The Economist Intelligence Unit report.[89] It also ranks as a very safe city (39th globally out of 162 cities overall) on the ranking of the safest and most dangerous countries.[90] As November 2024 the crime index from Numbeo places Athens at 55.40 (moderate), while its safety index is at 44.60.[91][92] According to a Mercer 2019 Quality of Living Survey, Athens ranks 89th on the Mercer Quality of Living Survey ranking.[93]

Economy

[edit]

Athens is the financial capital of Greece. According to data from 2014, Athens as a metropolitan economic area produced US$130 billion as GDP in PPP, which consists of nearly half of the production for the whole country. Athens was ranked 102nd in that year's list of global economic metropolises, while GDP per capita for the same year was 32,000 US dollars.[96]

Athens is one of the major economic centres in south-eastern Europe and is considered a regional economic power. The port of Piraeus, where big investments by COSCO have already been delivered during the recent decade, the completion of the new Cargo Centre in Thriasion,[97] the expansion of the Athens Metro and the Athens Tram, as well as the Hellenikon metropolitan park redevelopment in Elliniko and other urban projects, are the economic landmarks of the upcoming years.

Prominent Greek companies such as Hellas Sat, Hellenic Aerospace Industry, Mytilineos Holdings, Titan Cement, Hellenic Petroleum, Papadopoulos E.J., Folli Follie, Jumbo S.A., OPAP, and Cosmote have their headquarters in the metropolitan area of Athens. Multinational companies such as Ericsson, Sony, Siemens, Motorola, Samsung, Microsoft, Teleperformance, Novartis, Mondelez and Coca-Cola also have their regional research and development headquarters in the city. The banking sector is represented by National Bank of Greece, Alpha Bank, Eurobank, and Piraeus Bank, while the Bank of Greece is also situated in the City Centre. The Athens Stock Exchange was severely hit by the Greek government-debt crisis and the decision of the government to proceed into capital controls during summer 2015. As a whole the economy of Athens and Greece was strongly affected, while data showed a change from long recession to growth of 1.4% from 2017 onwards.[98]

Tourism is also a leading contributor to the economy of the city, as one of Europe's top destinations for city-break tourism, and also the gateway for excursions to both the islands and other parts of the mainland. Greece attracted 26.5 million visitors in 2015, 30.1 million visitors in 2017, and over 33 million in 2018, making Greece one of the most visited countries in Europe and the world, and contributing 18% to the country's GDP. Athens welcomed more than 5 million tourists in 2018, and 1.4 million were "city-breakers"; this was an increase by over a million city-breakers since 2013.[99]

Tourism

[edit]

Athens has been a destination for travellers since antiquity. Over the 2000s, the city's infrastructure and social amenities have improved, in part because of its successful bid to stage the 2004 Olympic Games.

The Greek Government, aided by the EU, has funded major infrastructure projects such as the state-of-the-art Eleftherios Venizelos International Airport,[100] the expansion of the Athens Metro system,[55] and the new Attiki Odos Motorway.[55]

In recent years, Athens has become more dynamic with the addition of numerous new bars and cafés and a growing presence of street art and graffiti, enhancing its urban edge and adding more tourist options alongside the city's archaeological sites and museums.[101]

Transport

[edit]

Athens is the country's major transportation hub. The city has Greece's largest airport and its largest port; Piraeus, too, is the largest container transport port in the Mediterranean, and the largest passenger port in Europe.

Athens is a major national hub for Intercity (Ktel) and international buses, as well as for domestic and international rail transport. Public transport is serviced by a variety of transportation means, making up the country's largest mass transit system. Transport for Athens operates a large bus and trolleybus fleet, the city's Metro, a Suburban Railway service[102] and a tram network, connecting the southern suburbs to the city centre.[103]

Bus transport

[edit]OSY (Greek: ΟΣΥ) (Odikes Sygkoinonies S.A.), a subsidiary company of OASA (Athens urban transport organisation), is the main operator of buses and trolleybuses in Athens. As of 2017, its network consists of around 322 bus lines, spanning the Athens Metropolitan Area, and making up a fleet of 2,375 buses and trolleybuses. Of those 2,375, 619 buses run on compressed natural gas, making up the largest fleet of natural gas-powered buses in Europe, and 354 are electric-powered (trolleybuses). All of the 354 trolleybuses are equipped to run on diesel in case of power failure.[104]

International links are provided by a number of private companies. National and regional bus links are provided by KTEL from two InterCity Bus Terminals; Kifissos Bus Terminal A and Liosion Bus Terminal B, both located in the north-western part of the city. Kifissos provides connections towards Peloponnese, North Greece, West Greece and some Ionian Islands, whereas Liosion is used for most of Central Greece. Both of these terminals will be replaced by a new Intercity Bus Terminal under construction in Eleonas due to be completed by 2027.

Railways

[edit]Athens is the hub of the country's national railway system (OSE), connecting the capital with major cities across Greece and abroad (Istanbul, Sofia, Belgrade and Bucharest).

The Athens Suburban Railway, referred to as the Proastiakos, connects Athens International Airport to the city of Kiato, 106 km (66 mi)[105] west of Athens, via Larissa station, the city's central rail station and the port of Piraeus. The length of Athens's commuter rail network extends to 120 km (75 mi),[105] and is expected to stretch to 281 km (175 mi) by 2010.[105]

The Athens Metro is operated by STASY S.A. (Greek: ΣΤΑΣΥ) (Statheres Sygkoinonies S.A.), a subsidiary company of OASA (Athens urban transport organisation), which provides public transport throughout the Athens Urban Area. While its main purpose is transport, it also houses Greek artifacts found during the construction of the system.[106] The Athens Metro runs three metro lines, namely Line 1 (Green Line), Line 2 (Red Line) and Line 3 (Blue Line) lines, of which the first was constructed in 1869, and the other two largely during the 1990s, with the initial new sections opened in January 2000. Line 1 mostly runs at ground level and the other two (Line 2 & 3) routes run entirely underground. A fleet of 42 trains, using 252 carriages, operates on the network,[107] with a daily occupancy of 1,353,000 passengers.[108]

Line 1 (Green Line) serves 24 stations, and is the oldest line of the Athens metro network. It runs from Piraeus station to Kifissia station and covers a distance of 25.6 km (15.9 mi). There are transfer connections with the Blue Line 3 at Monastiraki station and with the Red Line 2 at Omonia and Attiki stations. Line 2 (Red Line) runs from Anthoupoli station to Elliniko station and covers a distance of 17.5 km (10.9 mi).[107] The line connects the western suburbs of Athens with the southeast suburbs, passing through the centre of Athens. The Red Line has transfer connections with the Green Line 1 at Attiki and Omonia stations. There are also transfer connections with the Blue Line 3 at Syntagma station and with the tram at Syntagma, Syngrou Fix and Neos Kosmos stations. Line 3 (Blue Line) runs from Dimotiko Theatro station, through the central Monastiraki and Syntagma stations to Doukissis Plakentias avenue in the northeastern suburb of Halandri.[107] It then ascends to ground level and continues to Athens International Airport Eleftherios Venizelos using the suburban railway infrastructure, extending its total length to 39 km (24 mi).[107] The spring 2007 extension from Monastiraki westwards to Egaleo connected some of the main night life hubs of the city, namely those of Gazi (Kerameikos station) with Psirri (Monastiraki station) and the city centre (Syntagma station).The new stations Maniatika, Piraeus and Dimotiko Theatro, were completed on 10 October 2022,[109][110] connecting the biggest port of Greece, the Port of Piraeus, with Athens International Airport, the biggest airport of Greece.

The Athens Tram is operated by STASY S.A. (Statheres Sygkoinonies S.A.), a subsidiary company of Transport for Athens (OASA). It has a fleet of 35 Sirio type vehicles[111] and 25 Alstom Citadis type vehicles[112] which serve 48 stations,[111] employ 345 people with an average daily occupancy of 65,000 passengers.[111] The tram network spans a total length of 27 km (17 mi) and covers ten Athenian suburbs.[111] The network runs from Syntagma Square to the southwestern suburb of Palaio Faliro, where the line splits in two branches; the first runs along the Athens coastline toward the southern suburb of Voula, while the other heads toward Piraeus. The network covers the majority of the Athens coastline.[113]

Athens International Airport

[edit]

Athens is served by the Athens International Airport (ATH), located near the town of Spata, in the eastern Messoghia plain, some 35 km (22 mi) east of the centre of Athens.[114] The airport, awarded the "European Airport of the Year 2004" Award,[115] is intended as an expandable hub for air travel in southeastern Europe and was constructed in 51 months, costing 2.2 billion euros. It employs a staff of 14,000.[115]

Ferry

[edit]The Port of Piraeus is the largest port in Greece and one of the largest in Europe. Rafina and Lavrio act as alternative ports of Athens, connects the city with numerous Greek islands of the Aegean Sea, Evia while also serving the cruise ships that arrive.

Motorways

[edit]

Two main motorways of Greece begin in Athens, namely the A1/E75, heading north towards Greece's second largest city, Thessaloniki; and the border crossing of Evzones and the A8/E94 heading west, towards Greece's third largest city, Patras, which incorporated the GR-8A. Before their completion much of the road traffic used the GR-1 and the GR-8.

Athens's Metropolitan Area is served by the Attiki Odos toll motorway network: its main section, the A6, extends from the western industrial suburb of Elefsina to Athens International Airport; while two beltways, namely the Aigaleo Beltway (A65) and the Hymettus Beltway (A62) serve parts of western and eastern Athens respectively. The span of the Attiki Odos in all its length is 65 km (40 mi),[116] making it the largest metropolitan motorway network in all of Greece.

Education

[edit]

Located on Panepistimiou Street, the old campus of the University of Athens, the National Library, and the Athens Academy form the "Athens Trilogy" built in the mid-19th century. The largest and oldest university in Athens is the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Most of the functions of NKUA along National Technical University of Athens have been transferred to a campus in the eastern suburb of Zografou. The National Technical University of Athens old campus is located on Patision Street.

The University of West Attica is the second largest university in Athens. The seat of the university is located in the western area of Athens, where the philosophers of Ancient Athens delivered lectures. All the activities of UNIWA are carried out in the modern infrastructure of the three University Campuses within the metropolitan region of Athens (Egaleo Park, Ancient Olive Groove and Athens), which offer modern teaching and research spaces, entertainment and support facilities for all students. Other universities that lie within Athens are the Athens University of Economics and Business, the Panteion University, the Agricultural University of Athens and the University of Piraeus.

There are overall ten state-supported Institutions of Higher (or Tertiary) education located in the Athens Urban Area, these are by chronological order: Athens School of Fine Arts (1837), National Technical University of Athens (1837), National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (1837), Agricultural University of Athens (1920), Athens University of Economics and Business (1920), Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences (1927), University of Piraeus (1938), Harokopio University of Athens (1990), School of Pedagogical and Technological Education (2002), University of West Attica (2018). There are also several other private colleges, as they called formally in Greece, as the establishment of private universities is prohibited by the constitution. Many of them are accredited by a foreign state or university such as the American College of Greece and the Athens Campus of the University of Indianapolis.[117]

Culture

[edit]Archaeological hub and museums

[edit]

The city is a world centre of archaeological research. Alongside national academic institutions, such as the Athens University and the Archaeological Society, it is home to multiple archaeological museums, taking in the National Archaeological Museum, the Cycladic Museum, the Epigraphic Museum, the Byzantine & Christian Museum, as well as museums at the ancient Agora, Acropolis, Kerameikos, and the Kerameikos Archaeological Museum. The city is also the setting for the Demokritos laboratory for Archaeometry, alongside regional and national archaeological authorities forming part of the Greek Department of Culture.

Athens hosts 17 Foreign Archaeological Institutes which promote and facilitate research by scholars from their home countries. As a result, Athens has more than a dozen archaeological libraries and three specialised archaeological laboratories, and is the venue of several hundred specialised lectures, conferences and seminars, as well as dozens of archaeological exhibitions each year. At any given time, hundreds of international scholars and researchers in all disciplines of archaeology are to be found in the city.

Athens's most important museums include:

- the National Archaeological Museum, the largest archaeological museum in the country, and one of the most important internationally, as it contains a vast collection of antiquities. Its artefacts cover a period of more than 5,000 years, from late Neolithic Age to Roman Greece;

- the Benaki Museum with its several branches for each of its collections including ancient, Byzantine, Ottoman-era, Chinese art and beyond;

- the Byzantine and Christian Museum, one of the most important museums of Byzantine art;

- the National Art Gallery, the nation's eponymous leading gallery, which reopened in 2021 after renovation;

- the National Museum of Contemporary Art, which opened in 2000 in a former brewery building;

- the Numismatic Museum, housing a major collection of ancient and modern coins;

- the Museum of Cycladic Art, home to an extensive collection of Cycladic art, including its famous figurines of white marble;

- the New Acropolis Museum, opened in 2009, and replacing the old museum on the Acropolis. The new museum has proved considerably popular; almost one million people visited during the summer period June–October 2009 alone. A number of smaller and privately owned museums focused on Greek culture and arts are also to be found.

- the Kerameikos Archaeological Museum, a museum which displays artifacts from the burial site of Kerameikos. Much of the pottery and other artifacts relate to Athenian attitudes towards death and the afterlife, throughout many ages.

- the Jewish Museum of Greece, a museum which describes the history and culture of the Greek Jewish community.

Architecture

[edit]

Athens incorporates architectural styles ranging from Greco-Roman and Neoclassical to Modern. They are often to be found in the same areas, as Athens is not marked by a uniformity of architectural style. A visitor will quickly notice the absence of tall buildings: Athens has very strict height restriction laws in order to ensure the Acropolis Hill is visible throughout the city. Despite the variety in styles, there is evidence of continuity in elements of the architectural environment throughout the city's history.[118]

For the greatest part of the 19th century Neoclassicism dominated Athens, as well as some deviations from it such as Eclecticism, especially in the early 20th century. Thus, the Old Royal Palace was the first important public building to be built, between 1836 and 1843. Later in the mid and late 19th century, Theophil Freiherr von Hansen and Ernst Ziller took part in the construction of many neoclassical buildings such as the Athens Academy and the Zappeion Hall. Ziller also designed many private mansions in the centre of Athens which gradually became public, usually through donations, such as Schliemann's Iliou Melathron.

Beginning in the 1920s, modern architecture including Bauhaus and Art Deco began to exert an influence on almost all Greek architects, and buildings both public and private were constructed in accordance with these styles. Localities with a great number of such buildings include Kolonaki, and some areas of the centre of the city; neighbourhoods developed in this period include Kypseli.[119]

In the 1950s and 1960s during the extension and development of Athens, other modern movements such as the International style played an important role. The centre of Athens was largely rebuilt, leading to the demolition of a number of neoclassical buildings. The architects of this era employed materials such as glass, marble and aluminium, and many blended modern and classical elements.[120] After World War II, internationally known architects to have designed and built in the city included Walter Gropius, with his design for the US Embassy, and, among others, Eero Saarinen, in his postwar design for the east terminal of the Ellinikon Airport.

Urban sculpture

[edit]

Across the city numerous statues or busts are to be found. Apart from the neoclassicals by Leonidas Drosis at the Academy of Athens (Plato, Socrates, Apollo and Athena), others in notable categories include the statue of Theseus by Georgios Fytalis at Thiseion; depictions of philhellenes such as Lord Byron, George Canning, and William Gladstone; the equestrian statue of Theodoros Kolokotronis by Lazaros Sochos in front of the Old Parliament; statues of Ioannis Kapodistrias, Rigas Feraios and Adamantios Korais at the university; of Evangelos Zappas and Konstantinos Zappas at the Zappeion; Ioannis Varvakis at the National Garden; the" Woodbreaker" by Dimitrios Filippotis; the equestrian statue of Alexandros Papagos in the Papagou district; and various busts of fighters of Greek independence at the Pedion tou Areos. A significant landmark is also the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Syntagma.

Entertainment and performing arts

[edit]

Athens is home to 148 theatrical stages, more than any other city in the world, including the ancient Odeon of Herodes Atticus, home to the Athens Festival, which runs from May to October each year.[121][122] In addition to a large number of multiplexes, Athens plays host to open air garden cinemas. The city also supports music venues, including the Athens Concert Hall (Megaro Moussikis), which attracts world class artists.[123] The Athens Planetarium,[124] located in Andrea Syngrou Avenue, in Palaio Faliro[125] is one of the largest and best equipped digital planetaria in the world.[126] The Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, inaugurated in 2016, will house the National Library of Greece and the Greek National Opera.[127] In 2018 Athens was designated as the World Book Capital by UNESCO.[128]

Restaurants, tavernas and bars can be found in the entertainment hubs in Plaka and the Trigono areas of the historic centre, the inner suburbs of Gazi and Psyrri are especially busy with nightclubs and bars, while Kolonaki, Exarchia, Kypseli, Metaxourgeio, Koukaki and Pangrati offer more of a cafe and restaurant scene. The coastal suburbs of Microlimano, Alimos and Glyfada include many tavernas, beach bars and busy summer clubs.

The most successful songs during the period 1870–1930 were the Athenian serenades (Αθηναϊκές καντάδες), based on the Heptanesean kantádhes (καντάδες 'serenades'; sing.: καντάδα) and the songs performed on stage (επιθεωρησιακά τραγούδια 'theatrical revue songs') in revues, musical comedies, operettas and nocturnes that were dominating Athens's theatre scene.

In 1922, following the Greek-Turkish war, Greek genocide and later population exchange suffered by the Greek population of Asia Minor, many ethnic Greeks fled to Athens. They settled in poor neighbourhoods and brought with them Rebetiko music, making it also popular in Greece, and which later became the base for the Laïko music. Other forms of song popular today in Greece are elafrolaika, entechno, dimotika, and skyladika.[129] Greece's most notable, and internationally famous, composers of Greek song, mainly of the entechno form, are Manos Hadjidakis and Mikis Theodorakis. Both composers have achieved fame abroad for their composition of film scores.[129]

The renowned American-born Greek soprano Maria Callas spent her teenage years in Athens, where she settled in 1937.[130][131] Her professional opera career started in 1940 in Athens, with the Greek National Opera.[132] In 2018, the city's municipal Olympia Theatre was renamed the "Olympia City Music Theatre 'Maria Callas'"[133][134] and in 2023, the Municipality inaugurated the Maria Callas Museum, housing it in a neoclassical building on 44 Mitropoleos street.[135]

Sports

[edit]

Athens has a long tradition in sports and sporting events, serving as home to the most important clubs in Greek sport and housing a large number of sports facilities. The city has also been host to sports events of international importance.

Athens has hosted the Summer Olympic Games twice, in 1896 and 2004. The 2004 Summer Olympics required the development of the Athens Olympic Stadium, which has since gained a reputation as one of the most beautiful stadiums in the world, and one of its most interesting modern monuments.[136] The biggest stadium in the country, it hosted two finals of the UEFA Champions League, in 1994 and 2007. Other major stadiums are the Karaiskakis Stadium located in the nearby city of Piraeus, a sports and entertainment complex, host of the 1971 UEFA Cup Winners' Cup Final, and Agia Sophia Stadium located in Nea Filadelfeia, host of the 2024 UEFA Europa Conference League final.

The EuroLeague final has been hosted twice in 1985 and in 1993 at the Peace and Friendship Stadium, most known as SEF, a large indoor arena,[137] and the third time in 2007 at the Olympic Indoor Hall. Events in other sports such as athletics, volleyball, water polo etc., have been hosted in the capital's venues.

Greater Athens is home to three widely supported and successful multi-sport clubs, Panathinaikos, originated in the city of Athens, Olympiacos, originated in the port city of Piraeus and AEK, originated in the suburban town of Nea Filadelfeia. In football, Olympiacos is the dominant force at the national level and the only Greek club to have won a European competition, the 2023–24 UEFA Europa Conference League, Panathinaikos made it to the 1971 European Cup Final, while AEK Athens is the other member of the big three. These clubs also have successful basketball teams; Panathinaikos and Olympiacos are considered among the top powers in Europe, having won the EuroLeague seven and three times respectively, whilst AEK Athens was the first Greek team to win a European trophy in any team sport.

Other notable clubs within the region are Athinaikos, Panionios, Atromitos, Apollon, Panellinios, Egaleo F.C., Ethnikos Piraeus, Maroussi BC and Peristeri B.C. Athenian clubs have also had domestic and international success in other sports.

The Athens area encompasses a variety of terrain, notably hills and mountains rising around the city, and the capital is the only major city in Europe to be bisected by a mountain range. Four mountain ranges extend into city boundaries and thousands of kilometres of trails criss-cross the city and neighbouring areas, providing exercise and wilderness access on foot and on bicycle.

Beyond Athens and across the prefecture of Attica, outdoor activities include skiing, rock climbing, hang gliding and windsurfing. Numerous outdoor clubs serve these sports, including the Athens Chapter of the Sierra Club, which leads over 4,000 outings annually in the area.

Athens was awarded the 2004 Summer Olympics on 5 September 1997 in Lausanne, Switzerland, after having lost a previous bid to host the 1996 Summer Olympics, to Atlanta, United States.[22] It was to be the second time Athens would host the games, following the inaugural event of 1896. After an unsuccessful bid in 1990, the 1997 bid was radically improved, including an appeal to Greece's Olympic history. In the last round of voting, Athens defeated Rome with 66 votes to 41.[22] Prior to this round, the cities of Buenos Aires, Stockholm and Cape Town had been eliminated from competition, having received fewer votes.[22] Although the heavy cost was criticised, estimated at US$1.5 billion, Athens was transformed into a more functional city that enjoys modern technology both in transportation and in modern urban development.[138] The games welcomed over 10,000 athletes from 202 countries.[138]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Athens: City of Wisdom". Washington Independent Review of Books. 30 March 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Athens and Jerusalem: City of Reason, City of Faith". RANE Network. 15 July 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- ^ Municipality of Athens, Municipal elections – October 2023[permanent dead link], Ministry of Interior

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Census 2021 GR" (PDF) (Press release). Hellenic Statistical Authority. 19 July 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ "EU regions by GDP, Eurostat". www.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ Wells, John C. (1990). "Athens". Longman pronunciation dictionary. Harlow, England: Longman. p. 48. ISBN 0-582-05383-8.

- ^ a b "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Characteristics". Hellenic Interior Ministry. ypes.gr. Archived from the original on 4 January 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- ^ Vinie Daily, Athens, the city in your pocket, p. 6.

- ^ Greenberg, Mike; PhD (23 February 2021). "Athena Facts: Things that not many people know about..." Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ "Contents and Principles of the Programme of Unification of the Archaeological Sites of Athens". Hellenic Ministry of Culture. yppo.gr. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ CNN & Associated Press (16 January 1997). "Greece uncovers 'holy grail' of Greek archeology". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 December 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2007.

- ^ Encarta Ancient Greece from the Internet Archive– Retrieved on 28 February 2012. Archived 31 October 2009.

- ^ a b "Athens". Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

Ancient Greek Athenai, historic city and capital of Greece. Many of classical civilization's intellectual and artistic ideas originated there, and the city is generally considered to be the birthplace of Western civilization

- ^ a b BBC History on Greek Democracy Archived 19 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine – Accessed on 26 January 2007

- ^ "The World According to GaWC 2020". GaWC – Research Network. Globalization and World Cities. Archived from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Maritime passenger statistics". Eurostat. Eurostat. 21 November 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "World Shipping Council- Top 50 Ports". World Shipping Council. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ Monthly Statistical Bulletin of Greece, December 2012. ELSTAT. 2012. p. 64.

- ^ "Μόνιμος Πληθυσμός – ELSTAT". www.statistics.gr. Archived from the original on 5 January 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ "Athens, Greece Metro Area Population 1950–2023". www.macrotrends.net. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d CNN & Sports Illustrated (5 September 1997). "Sentiment a factor as Athens gets 2004 Olympics". sportsillustrated.cnn.com. Archived from the original on 19 May 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2007.

- ^ As for example in Od.7.80 Archived 18 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Beekes, Robert S. P. (2009), Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Leiden and Boston: Brill, p. 29

- ^ a b c Burkert, Walter (1985), Greek Religion, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, p. 139, ISBN 0-674-36281-0

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kerényi, Karl (1951), The Gods of the Greeks, London, England: Thames and Hudson, p. 124, ISBN 0-500-27048-1

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b Garland, Robert (2008). Ancient Greece: Everyday Life in the Birthplace of Western Civilization. New York: Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4549-0908-8.

- ^ Great Greek Encyclopedia, vol. II, Athens 1927, p. 30.

- ^ "ToposText". topostext.org. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Bourne, Edward G. (1887). "The Derivation of Stamboul". American Journal of Philology. 8 (1). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 78–82. doi:10.2307/287478. ISSN 0002-9475. JSTOR 287478.

- ^ 'General Storia' (Global History)

- ^ Osmanlı Yer Adları, Ankara 2017, s.v. full text Archived 31 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "v4.ethnos.gr – Οι πρώτοι… Αθηναίοι". Ethnos.gr. July 2011. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ S. Immerwahr, The Athenian Agora XIII: the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, Princeton 1971

- ^ a b c d e f Tung, Anthony (2001). "The City the Gods Besieged". Preserving the World's Great Cities: The Destruction and Renewal of the Historic Metropolis. New York: Three Rivers Press. p. 266. ISBN 0-609-80815-X.

- ^ Iakovides, S. 1962. 'E mykenaïke akropolis ton Athenon'. Athens.

- ^ Desborough, Vincent R. d'A (1964). The Last Mycenaeans and Their Successors; an Archaeological Survey, c. 1200–c. 1000 B.C. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 113.

- ^ Little, Lisa M. (1988). "A Social Outcast in Early Iron Age Athens". Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. 67, No. 4 (Oct. – Dec. 1998): 375–404. JSTOR 148450.

- ^ Osborne, R. 1996, 2009. Greece in the Making 1200–479 BC.[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ Lewis, John David (2010). Nothing Less than Victory: Decisive Wars and the Lessons of History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1400834303. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ^ Xenophon, Hellenica, 2.2.20, 404/3

- ^ Kouremenos, Anna (2022). "'The City of Hadrian and not of Theseus': A Cultural History of Hadrian's Arch". In A. Kouremenos (ed.) The Province of Achaea in the 2nd century CE: The Past Present. London: Routledge. https://www.academia.edu/43746490/_2022_The_City_of_Hadrian_and_not_of_Theseus_a_cultural_history_of_Hadrians_Arch

- ^ a b c d e f g Gregory, Timothy E.; Ševčenko, Nancy Patterson (1991). "Athens". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 221–223. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- ^ Alan Cameron, "The Last Days of the Academy at Athens," in A. Cameron, Wandering Poets and Other Essays on Late Greek Literature and Philosophy, 2016, (Oxford University Press: Oxford), pp. 205–246

- ^ a b c d e f Babinger, Franz (1986). "Atīna". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden and New York: Brill. pp. 738–739. ISBN 90-04-08114-3.

- ^ "Byzantine Athens: A provincial city in the shadow of its glorious past". 8 January 2025.

- ^ Augustinos, Olga (2007). "Eastern Concubines, Western Mistresses: Prévost's Histoire d'une Grecque moderne". In Buturović, Amila; Schick, İrvin Cemil (eds.). Women in the Ottoman Balkans: Gender, Culture and History. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-84511-505-0.

- ^ "and (Dontas, The Acropolis and its Museum, 16)". Ancient-greece.org. 21 April 2007. Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- ^ Wynn, Martin (1984). Planning and Urban Growth in Southern Europe. Mansell. p. 6. ISBN 978-0720116083.

- ^ "Focus on Athens" (PDF). UHI Quarterly Newsletter, Issue 1, May 2009. urbanheatisland.info. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ "Welcome!!!". Parnitha-np.gr. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ "Acropolis: Threat of Destruction". Time. 31 January 1977. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- ^ a b c d Kitsantonis, Niki (16 July 2007). "As forest fires burn, suffocated Athens is outraged". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 18 September 2007. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

- ^ Συνέντευξη Τύπου Γ. Σουφλιά για την Πάρνηθα (Press release) (in Greek). Hellenic Ministry for the Environment, Physical Planning, & Public Works. 18 July 2007. Archived from the original (.doc) on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

Συνολική καμένη έκταση πυρήνα Εθνικού Δρυμού Πάρνηθας: 15.723 (Σύνολο 38.000)

- ^ a b c "Olympic Games 2004: five major projects for Athens". European Union Regional Policy. ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 20 May 2007. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ^ "Eaxa :: Ενοποιηση Αρχαιολογικων Χωρων Αθηνασ Α.Ε". Astynet.gr. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- ^ "Περιφέρεια Αττικής". Retrieved 13 July 2025.

- ^ "Climate Atlas of Greece". Hellenic National Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Practical Information About Athens". www.ippcathens2024.gr. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ Melas, D.; Ziomas, I.; Klemm, O.; Zerefos, C. S. (1 June 1998). "Anatomy of the sea-breeze circulation in Athens area under weak large-scale ambient winds". Atmospheric Environment. 32 (12): 2223–2237. Bibcode:1998AtmEn..32.2223M. doi:10.1016/S1352-2310(97)00420-2. ISSN 1352-2310.

- ^ "Mountain Weather in Greece : Articles : SummitPost". www.summitpost.org. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ "Unusually heavy snow blankets Athens – in pictures". The Guardian. 16 February 2021. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ "Severe weather brings snow to Athens, Greek islands". Ekhatimerini. 24 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ Giannaros, Theodore M.; Melas, Dimitrios; Daglis, Ioannis A.; Keramitsoglou, Iphigenia; Kourtidis, Konstantinos (1 July 2013). "Numerical study of the urban heat island over Athens (Greece) with the WRF model". Atmospheric Environment. 73: 103–111. Bibcode:2013AtmEn..73..103G. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2013.02.055. ISSN 1352-2310.

- ^ Visram, Talib (23 July 2021). "Athens will be the first European city to appoint a chief heat officer". Fast Company. Fast Company media magazine. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ "Athens' chief heat officer prepares the city for the climate crisis". euronews. 24 June 2022. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization's World Weather & Climate Extremes Archive". Arizona State University website. World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ^ "WMO is monitoring potential new temperature records". public.wmo.int. 17 July 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ "Το 'νέο' κλίμα της Αθήνας – Περίοδος 1991–2020". National Observatory of Athens. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Το κλίμα της Αθήνας". www.meteoclub.gr. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ "Το αρχείο του Θησείου". www.meteoclub.gr. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.