Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Solar analog

View on Wikipedia

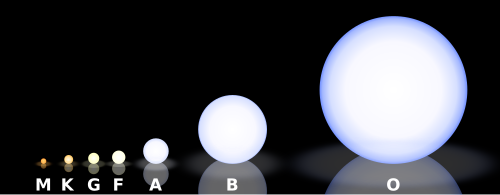

Solar-type stars, solar analogs (also analogues), and solar twins are stars that are particularly similar to the Sun. The stellar classification is a hierarchy with solar twin being most like the Sun followed by solar analog and then solar-type.[1] Observations of these stars are important for understanding better the properties of the Sun in relation to other stars and the habitability of planets.[2]

By similarity to the Sun

[edit]Defining the three categories by their similarity to the Sun reflects the evolution of astronomical observational techniques. Originally, solar-type was the closest that similarity to the Sun could be defined. Later, more precise measurement techniques and improved observatories allowed for greater precision of key details like temperature, enabling the creation of a solar analog category for stars that were particularly similar to the Sun. Later still, continued improvements in precision allowed for the creation of a solar-twin category for near-perfect matches.[citation needed]

Similarity to the Sun allows for checking derived quantities—such as temperature, which is derived from the color index—against the Sun, the only star whose temperature is confidently known. For stars that are not similar to the Sun, this cross-checking cannot be done.[1]

Solar-type

[edit]These stars are broadly similar to the Sun. They are main-sequence stars with a B−V color between 0.48 and 0.80, the Sun having a B−V color of 0.65. Alternatively, a definition based on spectral type can be used, such as F8V through K2V, which would correspond to B−V color of 0.50 to 1.00.[1] This definition fits approximately 10% of stars, so a list of solar-type stars would be quite extensive.[3]

Solar-type stars show highly correlated behavior between their rotation rates and their chromospheric activity (e.g. Calcium H & K line emission) and coronal activity (e.g. X-ray emission)[4] Because solar-type stars spin down during their main-sequence lifetimes due to magnetic braking, these correlations allow rough ages to be derived. Mamajek & Hillenbrand (2008)[5] have estimated the ages for the 108 solar-type (F8V–K2V) main-sequence stars within 52 light-years (16 parsecs) of the Sun based on their chromospheric activity (as measured via Ca, H, and K emission lines).[citation needed]

The following table shows a sample of solar-type stars within 50 light years that nearly satisfy the criteria for solar analogs (B−V color between 0.48 and 0.80), based on current measurements (the Sun is listed for comparison):

| Identifier | J2000 coordinates[6] | Distance[6] (ly) |

Stellar class[6] |

Temperature (K) |

Metallicity (dex) |

Age (Gyr) |

Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right ascension | Declination | |||||||

| Sun | — | — | 0.0000158 | G2V | 5778 | +0.00 | 4.6 | [7] |

| Rigil Kentaurus [8] | 15h 49m 36.49400s | −60° 50′ 02.3737″ | 4.37 | G2V | 5790 | +0.20 | 4.4 | [9][10][11][12] |

| Toliman | 4.37 | K0V | 5260 | 4.4 | ||||

| Epsilon Eridani [13] | -09h 27m 29.7s | 03° 32′ 55.8″ | 10.4 | K2V | 5084 | -0.13 | 0.4-0.8 | |

| Tau Ceti [14] | 01h 44m 04.1s | −15° 56′ 15″ | 11.9 | G8V | 5344 | –0.52 | 5.8 | [15] |

| 82 Eridani [16] | 03h 19m 55.7s | −43° 04′ 11.2″ | 19.8 | G8V | 5338 | –0.54 | 6.1 | [17] |

| Delta Pavonis [18] | 20h 08m 43.6s | −66° 10′ 55″ | 19.9 | G8IV | 5604 | +0.33 | ~7 | [19] |

| V538 Aurigae [20] | 05h 41m 20.3s | +53° 28′ 51.8″ | 39.9 | K1V | 5257 | −0.20 | 3.7 | [17] |

| HD 14412 [21] | 02h 18m 58.5s | −25° 56′ 45″ | 41.3 | G5V | 5432 | −0.46 | 9.6 | [17] |

| HR 4587 [22] | 12h 00m 44.3s | −10° 26′ 45.7″ | 42.1 | G8IV | 5538 | +0.18 | 8.5 | [17] |

| HD 172051 [23] | 18h 38m 53.4s | −21° 03′ 07″ | 42.7 | G5V | 5610 | −0.32 | 4.3 | [17] |

| 72 Herculis [24] | 17h 20m 39.6s | +32° 28′ 04″ | 46.9 | G0V | 5662 | −0.37 | 5 | [17] |

| HD 196761 [25] | 20h 40m 11.8s | −23° 46′ 26″ | 46.9 | G8V | 5415 | −0.31 | 6.6 | [19] |

| Nu² Lupi [26] | 15h 21m 48.1s | −48° 19′ 03″ | 47.5 | G4V | 5664 | −0.34 | 10.3 | [19] |

Solar analog

[edit]These stars are photometrically similar to the Sun, having the following qualities:[1]

- Temperature within 500 K from that of the Sun (5278 to 6278 K)

- Metallicity of 50–200% (± 0.3 dex) of that of the Sun, meaning the star's protoplanetary disk would have had similar amounts of dust from which planets could form

- No close companion (orbital period of ten days or less), because such a companion stimulates stellar activity

Solar analogs not meeting the stricter solar twin criteria include, within 50 light years and in order of increasing distance (The Sun is listed for comparison.):

| Identifier | J2000 coordinates[6] | Distance[6] (ly) |

Stellar class[6] |

Temperature (K) |

Metallicity (dex) |

Age (Gyr) |

Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right ascension | Declination | |||||||

| Sun | — | — | 0.0000158 | G2V | 5,778 | +0.00 | 4.6 | [7] |

| Sigma Draconis [27] | 19h 32m 21.6s | +69° 39′ 40″ | 18.8 | G9–K0 V | 5,297 | −0.20 | 4.7 | [28] |

| Beta Canum Venaticorum [29] | 12h 33m 44.5s | +41° 21′ 27″ | 27.4 | G0V | 5,930 | −0.30 | 6.0 | [17] |

| 61 Virginis [30] | 13h 18m 24.3s | −18° 18′ 40″ | 27.8 | G5V | 5,558 | −0.02 | 6.3 | [19] |

| Zeta Tucanae [31] | 00h 20m 04.3s | –64° 52′ 29″ | 28.0 | F9.5V | 5,956 | −0.14 | 2.5 | [15] |

| Beta Comae Berenices [32] | 13h 11m 52.4s | +27° 52′ 41″ | 29.8 | G0V | 5,970 | −0.06 | 2.0 | [17] |

| 61 Ursae Majoris [33] | 11h 41m 03.0s | +34° 12′ 06″ | 31.1 | G8V | 5,483 | −0.12 | 1.0 | [17] |

| HR 511 [34] | 01h 47m 44.8s | +63° 51′ 09″ | 32.8 | K0V | 5,333 | +0.05 | 3.0 | [17] |

| Alpha Mensae [35] | 06h 10m 14.5s | –74° 45′ 11″ | 33.1 | G5V | 5,594 | +0.10 | 5.4 | [15] |

| HD 69830 [36] | 08h 18m 23.9s | −12° 37′ 56″ | 40.6 | K0V | 5,410 | −0.03 | 10.6 | [15] |

| HD 10307 [37] | 01h 41m 47.1s | +42° 36′ 48″ | 41.2 | G1.5V | 5,848 | −0.05 | 7.0 | [17] |

| HD 147513 [38] | 16h 24m 01.3s | −39° 11′ 35″ | 42.0 | G1V | 5,858 | +0.03 | 0.4 | [19] |

| 58 Eridani [39] | 04h 47m 36.3s | −16° 56′ 04″ | 43.3 | G3V | 5,868 | +0.02 | 0.6 | [15] |

| 47 Ursae Majoris [40] | 10h 59m 28.0s | +40° 25′ 49″ | 45.9 | G1V | 5,954 | +0.06 | 6.0 | [15] |

| Psi Serpentis [41] | 15h 44m 01.8s | +02° 30′ 54.6″ | 47.8 | G5V | 5,683 | 0.04 | 3.2 | [42] |

| HD 84117 [43] | 09h 42m 14.4s | –23° 54′ 56″ | 48.5 | F8V | 6,167 | −0.03 | 3.1 | [15] |

| HD 4391 [44] | 00h 45m 45.6s | –47° 33′ 07″ | 48.6 | G3V | 5,878 | −0.03 | 1.2 | [15] |

| 20 Leonis Minoris [45] | 10h 01m 00.7s | +31° 55′ 25″ | 49.1 | G3V | 5,741 | +0.20 | 6.5 | [17] |

| Nu Phoenicis [46] | 01h 15m 11.1s | –45° 31′ 54″ | 49.3 | F8V | 6,140 | +0.18 | 5.7 | [15] |

| Helvetios [47] | 22h 57m 28.0s | +20° 46′ 08″ | 50.9 | G2.5IVa | 5,804 | +0.20 | 7.0 | [15] |

Solar twin

[edit]To date no solar twin that exactly matches the Sun has been found.[48] However, there are some stars that come very close to being identical to the Sun, and are such considered solar twins by members of the astronomical community. An exact solar twin would be a G2V star with a 5,778 K surface temperature, be 4.6 billion years old, with the correct metallicity and a 0.1% solar luminosity variation.[48] Stars with an age of 4.6 billion years are at the most stable state. Proper metallicity, radius, chemical composition, rotation, magnetic activity, and size are also very important to low luminosity variation.[49][50][51][52]

The stars below are more similar to the Sun and having the following qualities:[1]

- Temperature within 50 K from that of the Sun (5728 to 5828 K)[a] (within 10 K of sun (5768–5788 K)).

- Metallicity of 89–112% (± 0.05 dex) of that of the Sun, meaning the star's proplyd would have had almost exactly the same amount of dust for planetary formation

- No stellar companion, because the Sun itself is a solitary star

- An age within 1 billion years from that of the Sun (3.6 to 5.6 Ga)

Other Sun parameters:[53]

- Sun rotates on its axis once in about 27 days or 1.997 kilometres per second (1.241 mi/s)

- Sun radius is 700,000 kilometres (430,000 mi)

- Sun chemical composition by mass: hydrogen (73.4%); helium (25%); carbon (0.2%); nitrogen (0.09%);oxygen (0.80%); neon (0.16%); magnesium (0.06%); silicon (0.09&); sulfur (0.05%); iron (0.003%).[54]

The following are the known stars that come closest to satisfying the criteria for a solar twin. The Sun is listed for comparison. Highlighted boxes are out of range for a solar twin. The star may have been noted as solar twin in the past, but are more of a solar analog.

| Identifier | J2000 coordinates[6] | Distance[6] (ly) |

Stellar class[6] |

Temperature (K) |

Metallicity (dex) |

Age (Gyr) |

Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right ascension | Declination | |||||||

| Sun | — | — | 0.0000158 | G2V | 5,778 | +0.00 | 4.6 | [7] |

| 18 Scorpii [55] | 16h 15m 37.3s | –08° 22′ 06″ | 45.1 | G2Va | 5,433 | −0.03 | 2.9 | [56][57] |

| HD 150248 [58] | 16h 41m 49.8s | –45° 22′ 07″ | 88 | G2 | 5,750 | −0.04 | 6.2 | [57] |

| HD 164595 [59] | 18h 00m 38.9s | +29° 34′ 19″ | 91 | G2 | 5,810 | −0.06 | 4.5 | [57] |

| HD 195034 [60] | 20h 28m 11.8s | +22° 07′ 44″ | 92 | G5 | 5,760 | −0.04 | 2.9 | [61] |

| HD 117939 [62] | 13h 34m 32.6s | –38° 54′ 26″ | 98 | G3 | 5,730 | −0.10 | 6.1 | [57] |

| HD 138573 [63] | 15h 32m 43.7s | +10° 58′ 06″ | 99 | G5IV–V | 5,757 | +0.00 | 7.1 | [64] |

| HD 71334 [65] | 08h 25m 49.5s | −29° 55′ 50″ | 124 | G2 | 5,701 | −0.075 | 8.1 | [66] |

| HD 98649 [67] | 11h 20m 51.769s | –23° 13′ 02″ | 135 | G4V | 5,759 | −0.02 | 2.3 | [57] |

| HD 143436 [68] | 16h 00m 18.8s | +00° 08′ 13″ | 141 | G0 | 5,768 | +0.00 | 3.8 (±2.9) | [69] |

| HD 129357 [70] | 14h 41m 22.4s | +29° 03′ 32″ | 154 | G2V | 5,749 | −0.02 | 8.2 | [69] |

| HD 133600 [71] | 15h 05m 13.2s | +06° 17′ 24″ | 171 | G0 | 5,808 | +0.02 | 6.3 | [56] |

| HD 186302 [72] | 19h 49m 6.43s | −70° 11′ 16.7″ | 184 | G3 | 5,675 | +0.00 | 4.5 | [73] |

| HIP 11915 [74] | 02h 33m 49.02s | −19° 36′ 42.5″ | 190 | G5V | 5,760 | –0.059 | 4.1 | [75] |

| HD 101364 [76] | 11h 40m 28.5s | +69° 00′ 31″ | 208 | G5V | 5,795 | +0.02 | 7.1 | [56][77] |

| HD 197027 [78] | 20h 41m 54.6s | –27° 12′ 57″ | 250 | G3V | 5,723 | −0.013 | 8.2 | [79] |

| Kepler-452 [80] | 19h 44m 00.89s | +44° 16′ 39.2″ | 1400 | G2V | 5,757 | +0.21 | 6.0 | [81] |

| YBP 1194 [82] | 08h 51m 00.8s | +11° 48′ 53″ | 2934 | G5V | 5,780 | +0.023 | ~ 4.2 (± 1.6) | [83] |

Some other stars are sometimes mentioned as solar-twin candidates such as: Beta Canum Venaticorum; however it has too low metallicities (−0.21) for solar twin. 16 Cygni B is sometimes noted as twin, but is part of a triple star system and is very old for a solar twin at 6.8 Ga.

By potential habitability

[edit]Another way of defining solar twin is as a "habstar"—a star with qualities believed to be particularly hospitable to a life-hosting planet. Qualities considered include variability, mass, age, metallicity, and close companions.[84][b]

- At least 0.5–1 billion years old

- On the main sequence

- Non-variable

- Capable of harboring terrestrial planets

- Support a dynamically stable habitable zone

- 0–1 non-wide stellar companion stars.

The requirement that the star remain on the main sequence for at least 0.5–1 Ga sets an upper limit of approximately 2.2–3.4 solar masses, corresponding to a hottest spectral type of A0-B7V. Such stars can be 100x as bright as the Sun.[84][87] Tardigrade-like life (due to the UV flux) could potentially survive on planets orbiting stars as hot as B1V, with a mass of 10 M☉, and a temperature of 25,000 K, a main-sequence lifetime of about 20 million years.[c]

Non-variability is ideally defined as variability of less than 1%, but 3% is the practical limit due to limits in available data. Variation in irradiance in a star's habitable zone due to a companion star with an eccentric orbit is also a concern.[50][51][84][52]

Terrestrial planets in multiple star systems, those containing three or more stars, are not likely to have stable orbits in the long term. Stable orbits in binary systems take one of two forms: S-Type (satellite or circumstellar) orbits around one of the stars, and P-Type (planetary or circumbinary) orbits around the entire binary pair. Eccentric Jupiters may also disrupt the orbits of planets in habitable zones.[84]

Metallicity of at least 40% solar ([Fe/H] = −0.4) is required for the formation of an Earth-like terrestrial planet. High metallicity strongly correlates to the formation of hot Jupiters, but these are not absolute bars to life, as some gas giants end up orbiting within the habitable zone themselves, and could potentially host Earth-like moons.[84]

One example of such a star is HD 70642 [88], a G5V, at temperature of 5533 K, but is much younger than the Sun, at 1.9 billion years old.[89]

Another such example would be HIP 11915, which has a planetary system containing a Jupiter-like planet orbiting at a similar distance that the planet Jupiter does in the Solar System.[90] To strengthen the similarities, the star is class G5V, has a temperature of 5750 K, has a Sun-like mass and radius, and is only 500 million years younger than the Sun. As such, the habitable zone would extend in the same area as the zone in the Solar System, around 1 AU. This would allow an Earth-like planet to exist around 1 AU.[91]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ A true solar twins as noted by the Lowell Observatory should have a temperature within ~10 K of the Sun. Space Telescope Science Institute, Lowell Observatory, noted in 1996 that temperature precision of ~10 K can be measured. A temperature of ~10 K reduces the solar twin list to near zero, so ±50 K is used for the chart.[2]

- ^ habstar or habitability, is currently defined as an area, such as a planet or a moon, where liquid water can exist for at least a short duration of time.[85][86]

- ^ The supergiant and following supernova & neutron star (due to >8 M☉ mass) would likely destroy the life at the end of the B1V star's lifetime.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Soderblom, David R.; King, Jeremy R. (1998). "Solar-Type Stars: Basic Information on Their Classification and Characterization". In Jeffrey C. Hall (ed.). Solar Analogs: Characteristics and Optimum Candidates. The Second Annual Lowell Observatory Fall Workshop – October 5–7, 1997. Lowell Observatory. pp. 41–60. Bibcode:1998saco.conf...41S.

- ^ a b David R. Soderblom & Jeremy R. King (1998). "Solar-Type Stars: Basic Information on Their Classification and Characterization". Space Telescope Science Institute. Lowell Observatory: 41. Bibcode:1998saco.conf...41S. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ^ "The Classification of Stars". www.atlasoftheuniverse.com.

- ^ Baliunas, S. L.; Donahue, R. A.; Soon, J. H.; Horne, J. H.; Frazer, J.; Woodard-Eklund, L.; Bradford, M.; Rao, L. M.; Wilson, O. C.; Zhang, Q. (January 1, 1995). "Chromospheric variations in main-sequence stars". Astrophysical Journal, Part 1. 438 (1) – via ntrs.nasa.gov.

- ^ E. E. Mamajek; L. A. Hillenbrand (2008). "Improved Age Estimation for Solar-Type Dwarfs Using Activity-Rotation Diagnostics". Astrophysical Journal. 687 (2): 1264. arXiv:0807.1686. Bibcode:2008ApJ...687.1264M. doi:10.1086/591785. S2CID 27151456.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "SIMBAD Astronomical Database". SIMBAD. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- ^ a b c Williams, D.R. (2004). "Sun Fact Sheet". NASA. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

- ^ Alpha Centauri A at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600.

- ^ Wilkinson, John (2012). "The Sun and Stars". New Eyes on the Sun. Astronomers' Universe. pp. 219–236. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-22839-1_10. ISBN 978-3-642-22838-4. ISSN 1614-659X.

- ^ Thévenin, F.; Provost, J.; Morel, P.; Berthomieu, G.; Bouchy, F.; Carrier, F. (2002). "Asteroseismology and calibration of alpha Cen binary system". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 392: L9. arXiv:astro-ph/0206283. Bibcode:2002A&A...392L...9T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20021074. S2CID 17293259.

- ^ E. E. Mamajek; L. A. Hillenbrand (2008). "Improved Age Estimation for Solar-Type Dwarfs Using Activity-Rotation Diagnostics". Astrophysical Journal. 687 (2): 1264–1293. arXiv:0807.1686. Bibcode:2008ApJ...687.1264M. doi:10.1086/591785. S2CID 27151456.

- ^ Epsilon Eridani at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Tau Ceti at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Santos, N. C.; Israelian, G.; Randich, S.; García López, R. J.; Rebolo, R. (October 2004). "Beryllium anomalies in solar-type field stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 425 (3): 1013–1027. arXiv:astro-ph/0408109. Bibcode:2004A&A...425.1013S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20040510. S2CID 17279966.

- ^ 82 Eridani at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Holmberg J., Nordstrom B., Andersen J.; Nordström; Andersen (July 2009). "The Geneva-Copenhagen survey of the solar neighbourhood. III. Improved distances, ages, and kinematics". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 501 (3): 941–947. arXiv:0811.3982. Bibcode:2009A&A...501..941H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200811191. S2CID 118577511.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) See Vizier catalogue V/130. - ^ Delta Pavonis at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ a b c d e Sousa, S. G.; et al. (August 2008). "Spectroscopic parameters for 451 stars in the HARPS GTO planet search program. Stellar [Fe/H] and the frequency of exo-Neptunes". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 487 (1): 373–381. arXiv:0805.4826. Bibcode:2008A&A...487..373S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809698. S2CID 18173201. See VizieR catalogue J/A+A/487/373.

- ^ V538 Aurigae at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HD 14412 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HR 4587 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HD 172051 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ 72 Herculis at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HD 196761 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ nu2 lupi at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Sigma Draconis at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Boyajian, Tabetha S.; et al. (August 2008). "Angular Diameters of the G Subdwarf µ Cassiopeiae A and the K Dwarfs s Draconis and HR 511 from Interferometric Measurements with the CHARA Array". The Astrophysical Journal. 683 (1): 424–432. arXiv:0804.2719. Bibcode:2008ApJ...683..424B. doi:10.1086/589554. S2CID 8886682.

- ^ Beta Canum Venaticorum at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ 61 Virginis at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Zeta Tucanae at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Beta Comae Berenices at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ 61 Ursae Majoris at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HR 511 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Alpha Mensae at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HD 69830 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HD 10307 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HD 147513 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ 58 Eridani at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ 47 Ursae Majoris at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Psi Serpentis at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Mahdi, D.; et al. (March 2016). "Solar twins in the ELODIE archive". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 587: 9. arXiv:1601.01599. Bibcode:2016A&A...587A.131M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527472. S2CID 119205608. A131.

- ^ HD 84117 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HD 4391 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ 20 Leonis Minoris at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Nu Phoenicis at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ 51 Pegasi at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ a b "Solar Variability and Terrestrial Climate - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov.

- ^ Mahdi, D.; Soubiran, C.; Blanco-Cuaresma, S.; Chemin, L. (March 1, 2016). "Solar twins in the ELODIE archive". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 587: A131. arXiv:1601.01599. Bibcode:2016A&A...587A.131M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527472 – via www.aanda.org.

- ^ a b "Stellar Luminosity Calculator". astro.unl.edu.

- ^ a b The Effects of Solar Variability on Earth's Climate: A Workshop Report. National Academies Press. November 12, 2012. doi:10.17226/13519. ISBN 978-0-309-26564-5.

- ^ a b "Most of Earth's twins aren't identical, or even close! | ScienceBlogs". scienceblogs.com.

- ^ "15.1 The Structure and Composition of the Sun". January 23, 2017 – via pressbooks.online.ucf.edu.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bjarne Rosenkilde Jørgensen, “The G Dwarf Problem: Analysis of a New Data Set,” Astronomy & Astrophysics 363, November 2000, 947

- ^ 18 Scorpii at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ a b c Meléndez, Jorge; Ramírez, Iván (November 2007). "HIP 56948: A Solar Twin with a Low Lithium Abundance". The Astrophysical Journal. 669 (2): L89 – L92. arXiv:0709.4290. Bibcode:2007ApJ...669L..89M. doi:10.1086/523942. S2CID 15952981.

- ^ a b c d e Porto de Mello, G. F.; da Silva, R.; da Silva, L. & de Nader, R. V. (March 2014). "A photometric and spectroscopic survey of solar twin stars within 50 parsecs of the Sun; I. Atmospheric parameters and color similarity to the Sun". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 563: A52. arXiv:1312.7571. Bibcode:2014A&A...563A..52P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322277. S2CID 119111150.

- ^ HD 150248 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HD 164595 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HD 195034 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Takeda, Yoichi; Tajitsu, Akito (2009). "High-Dispersion Spectroscopic Study of Solar Twins: HIP 56948, HIP 79672, and HIP 100963". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. 61 (3): 471–478. arXiv:0901.2509. Bibcode:2009PASJ...61..471T. doi:10.1093/pasj/61.3.471.

- ^ HD 117939 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HD 138573 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Mahdi, D.; et al. (March 2016), "Solar twins in the ELODIE archive", Astronomy & Astrophysics, 587: 9, arXiv:1601.01599, Bibcode:2016A&A...587A.131M, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527472, S2CID 119205608, A131.

- ^ HD 71334 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Carlos, Marília; Nissen, Poul E.; Meléndez, Jorge (2016). "Correlation between lithium abundances and ages of solar twin stars". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 587: A100. arXiv:1601.05054. Bibcode:2016A&A...587A.100C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201527478. S2CID 119268561.

- ^ HD 98649 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HD 143436 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ a b King, Jeremy R.; Boesgaard, Ann M.; Schuler, Simon C. (November 2005). "Keck HIRES Spectroscopy of Four Candidate Solar Twins". The Astronomical Journal. 130 (5): 2318–2325. arXiv:astro-ph/0508004. Bibcode:2005AJ....130.2318K. doi:10.1086/452640. S2CID 6535115.

- ^ HD 129357 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HD 133600 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ HD 186302 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Adibekyan, V.; et al. (November 2018). "The AMBRE project: searching for the closest solar siblings". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 619: 19. arXiv:1601.01599. Bibcode:2016A&A...587A.131M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201834285. S2CID 119205608. A130.

- ^ HIP 11915 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ M. Bedell; J. Meléndez; J. L. Bean; I. Ramírez; M. Asplund; A. Alves-Brito; L. Casagrande; S. Dreizler; T. Monroe; L. Spina; M. Tucci Maia (June 26, 2015). "The Solar Twin Planet Search II. A Jupiter twin around a solar twin" (PDF). Astronomy and Astrophysics. 581: 8. arXiv:1507.03998. Bibcode:2015A&A...581A..34B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201525748. S2CID 56004595. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ HIP 56948 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Vázquez, M.; Pallé, E.; Rodríguez, P. Montañés (2010). "Is Our Environment Special?". The Earth as a Distant Planet: A Rosetta Stone for the Search of Earth-Like Worlds. Astronomy and Astrophysics Library. Springer New York. pp. 391–418. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1684-6. ISBN 978-1-4419-1683-9. See table 9.1.

- ^ HIP 102152 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ Monroe, T. R.; et al. (2013). "High Precision Abundances of the Old Solar Twin HIP 102152: Insights on Li Depletion from the Oldest Sun". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 774 (2): 22. arXiv:1308.5744. Bibcode:2013ApJ...774L..32M. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/774/2/L32. S2CID 56111132.

- ^ Kepler-452 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ "Planet Kepler-452 b". Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ Cl* NGC 2682 YBP 1194 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ A. Önehag; A. Korn; B. Gustafsson; E. Stempels; D. A. VandenBerg (2011). "M67-1194, an unusually Sun-like solar twin in M67". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 528: A85. arXiv:1009.4579. Bibcode:2011A&A...528A..85O. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015138. S2CID 119116626.

- ^ a b c d e Turnbull, Margaret C.; Tarter, Jill C. (2002). "Target Selection for SETI. I. A Catalog of Nearby Habitable Stellar Systems". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 145 (1): 181–198. arXiv:astro-ph/0210675. Bibcode:2003ApJS..145..181T. doi:10.1086/345779. S2CID 14734094.

- ^ "Sol Company, solstation.com, Stars and Habitable Planets, 2012".

- ^ "Habitable zone | Astrobiology, Exoplanets & Habitability | Britannica". www.britannica.com.

- ^ Mike Wall (January 6, 2013). "Double-Star Systems Can Be Dangerous for Exoplanets". Space.com.

- ^ HD 70642 at SIMBAD - Ids - Bibliography - Image.

- ^ "Solar System 'twin' found". BBC News. 2003-07-03.

- ^ "Jupiter Twin Discovered Around Solar Twin". eso.org/. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ^ "Solar Variability and Terrestrial Climate – NASA Science". Retrieved 8 January 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Lockwood, George Wesley; Skiff, Brian A.; Radick, Richard R. (1997). "The Photometric Variability of Sun-like Stars: Observations and Results, 1984—1995". The Astrophysical Journal. 485 (2): 789–811. Bibcode:1997ApJ...485..789L. doi:10.1086/304453.

- Porto de Mello, Gustavo Frederico; da Silva, Ronaldo; da Silva, Licio (2000). "A Survey of Solar Twin Stars within 50 Parsecs of the Sun". Bioastronomy 99: A New Era in the Search for Life. 213: 73. Bibcode:2000ASPC..213...73P.

- Turnbull, Margaret C.; Tarter, Jill C. (2003). "Target Selection for SETI. II. Tycho-2 Dwarfs, Old Open Clusters, and the Nearest 100 Stars". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 149 (2): 423–436. Bibcode:2003ApJS..149..423T. doi:10.1086/379320.

- Hall, Jeffrey C.; Lockwood, George Wesley (2004). "The Chromospheric Activity and Variability of Cycling and Flat Activity Solar-Analog Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 614 (2): 942–946. Bibcode:2004ApJ...614..942H. doi:10.1086/423926.

- do Nascimento Jr., Jose Dias; Castro, Matthieu Sebastien; Meléndez, Jorge; Bazot, Michaël; Théado, Sylvie; Porto de Mello, Gustavo Frederico; De Medeiros, José Renan (2009). "Age and mass of solar twins constrained by lithium abundance". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 501 (1): 687–694. arXiv:0904.3580. Bibcode:2009A&A...501..687D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200911935. S2CID 9565600.