Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Alpha Centauri

View on Wikipedia

Alpha Centauri AB (left) forms a triple star system with Proxima Centauri (below, south of, α Centauri AB). (See labelled version) | |

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Centaurus |

| α Centauri A (Rigil Kentaurus) | |

| Right ascension | 14h 39m 36.49400s[1] |

| Declination | −60° 50′ 02.3737″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | +0.01[2] |

| α Centauri B (Toliman) | |

| Right ascension | 14h 39m 35.06311s[1] |

| Declination | −60° 50′ 15.0992″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | +1.33[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| A | |

| Spectral type | G2V[3] |

| B−V colour index | +0.71[2] |

| B | |

| Spectral type | K1V[3] |

| B−V colour index | +0.88[2] |

| Astrometry | |

| A | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −21.4±0.76[4] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −3679.25[1] mas/yr Dec.: +473.67[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 750.81±0.38 mas[5] |

| Distance | 4.344 ± 0.002 ly (1.3319 ± 0.0007 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 4.38[6] |

| B | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −18.6±1.64[4] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −3614.39[1] mas/yr Dec.: +802.98[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 750.81±0.38 mas[5] |

| Distance | 4.344 ± 0.002 ly (1.3319 ± 0.0007 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 5.71[6] |

| Orbit[5] | |

| Primary | A |

| Companion | B |

| Period (P) | 79.762±0.019 yr |

| Semi-major axis (a) | 17.493±0.0096" (23.299 AU[b]) |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0.51947±0.00015 |

| Inclination (i) | 79.243±0.0089° |

| Longitude of the node (Ω) | 205.073±0.025° |

| Periastron epoch (T) | 1875.66±0.012 |

| Argument of periastron (ω) (secondary) | 231.519±0.027° |

| Details | |

| α Centauri A | |

| Mass | 1.0788±0.0029[5] M☉ |

| Radius | 1.2175±0.0055[5] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 1.5059±0.0019[5] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.30[7] cgs |

| Temperature | 5,804±13[8] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | 0.20±0.01[8] dex |

| Rotation | 28.3±0.5 d[9] |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 2.7±0.7[10] km/s |

| Age | 5.26±0.95[11] Gyr |

| α Centauri B | |

| Mass | 0.9092±0.0025[5] M☉ |

| Radius | 0.8591±0.0036[5] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 0.4981±0.0007[5] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.37[7] cgs |

| Temperature | 5,207±12[8] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | 0.24±0.01[8] dex |

| Rotation | 36.7±0.3 d[12] |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 1.1±0.8[13] km/s |

| Age | 5.26±0.95[11] Gyr |

| Other designations | |

| Gliese 559, FK5 538, CD−60°5483, CCDM J14396-6050, GC 19728 | |

| α Cen A: Rigil Kentaurus, Rigil Kent, α1 Centauri, HR 5459, HD 128620, GCTP 3309.00, LHS 50, SAO 252838, HIP 71683 | |

| α Cen B: Toliman, α2 Centauri, HR 5460, HD 128621, LHS 51, HIP 71681 | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | AB |

| A | |

| B | |

| Exoplanet Archive | data |

| ARICNS | data |

Alpha Centauri (α Centauri, α Cen, or Alpha Cen) is a star system in the southern constellation of Centaurus. It consists of three stars: Rigil Kentaurus (α Centauri A), Toliman (α Centauri B), and Proxima Centauri (α Centauri C).[14] Proxima Centauri is the closest star to the Sun at 4.2465 light-years (ly), which is 1.3020 parsecs (pc), while Alpha Centauri A and B are the nearest stars visible to the naked eye.

Rigil Kentaurus and Toliman are Sun-like stars (class G and K, respectively) that together form the binary star system α Centauri AB. To the naked eye, these two main components appear to be a single star with an apparent magnitude of −0.27. It is the brightest star in the constellation and the third-brightest in the night sky, outshone by only Sirius and Canopus. α Centauri AB are the nearest binary stars to the Sun at a distance of 4.344 ly (1.33 pc).

Rigil Kentaurus has 1.1 times the mass (M☉) and 1.5 times the luminosity of the Sun (L☉), while Toliman is smaller and cooler, at 0.9 M☉ and less than 0.5 L☉.[15] The pair orbit around a common centre with an orbital period of 79 years.[16] Their elliptical orbit is eccentric, so that the distance between A and B varies from 35.6 astronomical units (AU), or about the distance between Pluto and the Sun, to 11.2 AU, or about the distance between Saturn and the Sun.

Proxima Centauri is a small faint red dwarf (class M). Though not visible to the naked eye, Proxima Centauri is the closest star to the Sun at a distance of 4.24 ly (1.30 pc), slightly closer than α Centauri AB. The distance between Proxima Centauri and α Centauri AB is about 13,000 AU (0.21 ly),[17] equivalent to about 430 times the radius of Neptune's orbit.

Proxima Centauri has two confirmed planets — Proxima b and Proxima d. The former is an Earth-sized planet in the habitable zone (though it is unlikely to be habitable) while the latter is a sub-Earth which orbits very closely to the star.[18] A possible but disputed third planet, Proxima c, is a mini-Neptune 1.5 astronomical units away.[19] Rigil Kentaurus may have a Saturn-mass planet in the habitable zone, though it is not yet known with certainty to be planetary in nature.[20][21][22] Toliman has no known planets.[23]

Etymology and nomenclature

[edit]α Centauri (Latinised to Alpha Centauri) is the system's designation given by J. Bayer in 1603. It belongs to the constellation Centaurus, named after the part human, part horse creature in Greek mythology; Heracles accidentally wounded the centaur and placed him in the sky after his death. Alpha Centauri marks the right front hoof of the Centaur.[24] The common name Rigil Kentaurus is a Latinisation of the Arabic translation رجل القنطورس Rijl al-Qinṭūrus, meaning "the Foot of the Centaur".[25][26] Qinṭūrus is the Arabic transliteration of the Greek Κένταυρος (Kentaurus).[27] The name is frequently abbreviated to Rigil Kent (/ˈraɪdʒəl ˈkɛnt/) or even Rigil, though the latter name is better known for Rigel (β Orionis).[28][29][30][25][31][c]

An alternative name found in European sources, Toliman, is an approximation of the Arabic الظليمان aẓ-Ẓalīmān (in older transcription, aṭ-Ṭhalīmān), meaning 'the (two male) Ostriches', an appellation Zakariya al-Qazwini had applied to the pair of stars Lambda and Mu Sagittarii; it was often unclear on old star maps which name was intended to go with which star (or stars), and the referents changed over time.[35] The name Toliman originates with Jacob Golius' 1669 edition of Al-Farghani's Compendium. Tolimân is Golius' Latinisation of the Arabic name الظلمان al-Ẓulmān "the ostriches", the name of an asterism of which Alpha Centauri formed the main star.[36][37][38][39]

α Centauri C was discovered in 1915 by Robert T. A. Innes,[40] who suggested that it be named Proxima Centaurus,[41] from Latin 'the nearest [star] of Centaurus'.[42] The name Proxima Centauri later became more widely used and is now listed by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) as the approved proper name;[43][44] it is frequently abbreviated to Proxima.

In 2016, the Working Group on Star Names of the IAU,[14] having decided to attribute proper names to individual component stars rather than to multiple systems,[45] approved the name Rigil Kentaurus (/ˈraɪdʒəl kɛnˈtɔːrəs/) as being restricted to α Centauri A and the name Proxima Centauri (/ˈprɒksɪmə sɛnˈtɔːraɪ/) for α Centauri C.[46] On 10 August 2018, the IAU approved the name Toliman (/ˈtɒlɪmæn/) for α Centauri B.[47]

Other names

[edit]During the 19th century, the northern amateur popularist E.H. Burritt used the now-obscure name Bungula (/ˈbʌŋɡjuːlə/).[48] Its origin is not known, but it may have been coined from the Greek letter beta (β) and Latin ungula 'hoof', originally for Beta Centauri (the other hoof).[28][25]

In Chinese astronomy, 南門 Nán Mén, meaning Southern Gate, refers to an asterism consisting of Alpha Centauri and Epsilon Centauri. Consequently, the Chinese name for Alpha Centauri itself is 南門二 Nán Mén Èr, the Second Star of the Southern Gate.[49]

To the Indigenous Boorong people of northwestern Victoria in Australia, Alpha Centauri and Beta Centauri are Bermbermgle,[50] two brothers noted for their courage and destructiveness, who speared and killed Tchingal "The Emu" (the Coalsack Nebula).[51] The form in Wotjobaluk is Bram-bram-bult.[50]

Observation

[edit]

To the naked eye, α Centauri AB appear to be a single star, the brightest in the southern constellation of Centaurus.[52] Their apparent angular separation varies over about 80 years between 2 and 22 arcseconds (the naked eye has a resolution of 60 arcsec),[53] but through much of the orbit, both are easily resolved in binoculars or small telescopes.[54] At −0.27 apparent magnitude (combined for A and B magnitudes ), Alpha Centauri is a first-magnitude star and is fainter only than Sirius and Canopus.[52] It is the outer star of The Pointers or The Southern Pointers,[54] so called because the line through Beta Centauri (Hadar/Agena),[55] some 4.5° west,[54] points to the constellation Crux—the Southern Cross.[54][56] The Pointers easily distinguish the true Southern Cross from the fainter asterism known as the False Cross.[57]

South of about 29° South latitude, α Cen is circumpolar and never sets below the horizon.[d] North of about 29° N latitude, Alpha Centauri never rises. Alpha Centauri lies close to the southern horizon when viewed from latitude 29° N to the equator (close to Hermosillo and Chihuahua City in Mexico; Galveston, Texas; Ocala, Florida; and Lanzarote, the Canary Islands of Spain), but only for a short time around its culmination.[55] The star culminates each year at local midnight on 24 April and at local 9 p.m. on 8 June.[55][58]

As seen from Earth, Proxima Centauri is 2.2° southwest from α Centauri AB; this distance is about four times the angular diameter of the Moon.[59] Proxima Centauri appears as a deep-red star of a typical apparent magnitude of 11.1 in a sparsely populated star field, requiring moderately sized telescopes to be seen. Listed as V645 Cen in the General Catalogue of Variable Stars, version 4.2, this UV Ceti star or "flare star" can unexpectedly brighten rapidly by as much as 0.6 magnitude at visual wavelengths, then fade after only a few minutes.[60] Some amateur and professional astronomers regularly monitor for outbursts using either optical or radio telescopes.[61] In August 2015, the largest recorded flares of the star occurred, with the star becoming 8.3 times brighter than normal on 13 August, in the B band (blue light region).[62]

Observational history

[edit]Alpha Centauri is listed in the 2nd century star catalog appended to Ptolemy's Almagest. Ptolemy gave its ecliptic coordinates, but texts differ as to whether the ecliptic latitude reads 44° 10′ south or 41° 10′ south[63] (presently the ecliptic latitude is 43.5° south, but it has decreased by a fraction of a degree since Ptolemy's time due to proper motion). In Ptolemy's time, Alpha Centauri was visible from Alexandria, Egypt, at 31° N, but, due to precession, its declination is now –60° 51′ South, and it can no longer be seen at that latitude. English explorer Robert Hues brought Alpha Centauri to the attention of European observers in his 1592 work Tractatus de Globis, along with Canopus and Achernar, noting:

Now, therefore, there are but three Stars of the first magnitude that I could perceive in all those parts which are never seene here in England. The first of these is that bright Star in the sterne of Argo which they call Canobus [Canopus]. The second [Achernar] is in the end of Eridanus. The third [Alpha Centauri] is in the right foote of the Centaure.[64]

The binary nature of Alpha Centauri AB was recognized in December 1689 by Jean Richaud, while observing a passing comet from his station in Puducherry. Alpha Centauri was only the third binary star to be discovered, preceded by Mizar AB and Acrux.[65]

The large proper motion of Alpha Centauri AB was discovered by Manuel John Johnson, observing from Saint Helena, who informed Thomas Henderson at the Royal Observatory, Cape of Good Hope of it. The parallax of Alpha Centauri was subsequently determined by Henderson from many exacting positional observations of the AB system between April 1832 and May 1833. He withheld his results, however, because he suspected they were too large to be true, but eventually published them in 1839 after Bessel released his own accurately determined parallax for 61 Cygni in 1838.[66] For this reason, Alpha Centauri is sometimes considered as the second star to have its distance measured because Henderson's work was not fully acknowledged at first.[66] (The distance of Alpha Centauri from the Earth is now reckoned at 4.396 light-years or 4.159×1013 km.)

John Herschel made the first micrometrical observations in 1834.[67] Since the early 20th century, measures have been made with photographic plates.[68]

By 1926, William Stephen Finsen calculated the approximate orbit elements close to those now accepted for this system.[69] All future positions are now sufficiently accurate for visual observers to determine the relative places of the stars from a binary star ephemeris.[70] Others, like D. Pourbaix (2002), have regularly refined the precision of new published orbital elements.[16]

Robert T. A. Innes discovered Proxima Centauri in 1915 by blinking photographic plates taken at different times during a proper motion survey. These showed large proper motion and parallax similar in both size and direction to those of α Centauri AB, which suggested that Proxima Centauri is part of the α Centauri system and slightly closer to Earth than α Centauri AB. As a result, Innes concluded that Proxima Centauri was the closest star to Earth yet discovered.

Location and motion

[edit]Alpha Centauri may be inside the G-cloud of the Local Bubble,[71] and its nearest known system is the binary brown dwarf system Luhman 16, at 3.6 light-years (1.1 parsecs) distance.[72][failed verification]

Historical distance estimates

[edit]Alpha Centauri AB historical distance estimates Source Year Subject Parallax (mas) Distance References parsecs light-years petametres H. Henderson 1839 AB 1160±110 0.86+0.09

−0.072.81 ± 0.53 26.6+2.8

−2.3[73] T. Henderson 1842 AB 912.8±64 1.10 ± 0.15 3.57 ± 0.5 33.8+2.5

−2.2[74] Maclear 1851 AB 918.7±34 1.09±0.04 3.55+0.14

−0.1332.4 ± 2.5 [75] Moesta 1868 AB 880±68 1.14+0.10

−0.083.71+0.31

−0.2735.1+2.9

−2.5[76] Gill & Elkin 1885 AB 750±10 1.333±0.018 4.35±0.06 41.1+0.6

−0.5[77] Roberts 1895 AB 710±50 1.32 ± 0.2 4.29 ± 0.65 43.5+3.3

−2.9[78] Woolley et al. 1970 AB 743±7 1.346±0.013 4.39±0.04 41.5±0.4 [79] Gliese & Jahreiß 1991 AB 749.0±4.7 1.335±0.008 4.355±0.027 41.20±0.26 [80] van Altena et al. 1995 AB 749.9±5.4 1.334±0.010 4.349+0.032

−0.03141.15+0.30

−0.29[81] Perryman et al. 1997 AB 742.12±1.40 1.3475±0.0025 4.395±0.008 41.58±0.08[82][83] Söderhjelm 1999 AB 747.1±1.2 1.3385+0.0022

−0.00214.366±0.007 41.30±0.07 [84] van Leeuwen 2007 A 754.81±4.11 1.325±0.007 4.321+0.024

−0.02340.88±0.22 [85] B 796.92±25.90 1.25±0.04 4.09+0.14

−0.1337.5 ± 2.5 [86] RECONS TOP100 2012 AB 747.23±1.17[e] 1.3383±0.0021 4.365±0.007 41.29±0.06 [87]

Kinematics

[edit]

All components of α Centauri display significant proper motion against the background sky. Over centuries, this causes their apparent positions to slowly change.[88] Proper motion was unknown to ancient astronomers. Most assumed that the stars were permanently fixed on the celestial sphere, as stated in the works of the philosopher Aristotle.[89] In 1718, Edmond Halley found that some stars had significantly moved from their ancient astrometric positions.[90]

In the 1830s, Thomas Henderson discovered the true distance to α Centauri by analysing his many astrometric mural circle observations.[73][91] He then realised this system also likely had a high proper motion.[92][93][69] In this case, the apparent stellar motion was found using Nicolas Louis de Lacaille's astrometric observations of 1751–1752,[94] by the observed differences between the two measured positions in different epochs.

Calculated proper motion of the centre of mass for α Centauri AB is about 3620 mas/y (milliarcseconds per year) toward the west and 694 mas/y toward the north, giving an overall motion of 3686 mas/y in a direction 11° north of west.[95][f] The motion of the centre of mass is about 6.1 arcmin each century, or 1.02° each millennium. The speed in the western direction is 23.0 km/s (14.3 mi/s) and in the northerly direction 4.4 km/s (2.7 mi/s). Using spectroscopy the mean radial velocity has been determined to be around 22.4 km/s (13.9 mi/s) towards the Solar System.[95] This gives a speed with respect to the Sun of 32.4 km/s (20.1 mi/s), very close to the peak in the distribution of speeds of nearby stars.[96]

Since α Centauri AB is almost exactly in the plane of the Milky Way as viewed from Earth, many stars appear behind it. In early May 2028, α Centauri A will pass between the Earth and the distant red star 2MASS 14392160-6049528, when there is a 45% probability that an Einstein ring will be observed. Other conjunctions will also occur in the coming decades, allowing accurate measurement of proper motions and possibly giving information on planets.[95]

Predicted future changes

[edit]

Based on the system's common proper motion and radial velocities, α Centauri will continue to change its position in the sky significantly and will gradually brighten. For example, in about 6,200 CE, α Centauri's true motion will cause an extremely rare first-magnitude stellar conjunction with Beta Centauri, forming a brilliant optical double star in the southern sky.[56] It will then pass just north of the Southern Cross or Crux, before moving northwest and up towards the present celestial equator and away from the galactic plane. By about 26,700 CE, in the present-day constellation of Hydra, α Centauri will reach perihelion at 0.90 pc or 2.9 ly away,[97] though later calculations suggest that this will occur in 27,000 AD.[98] At its nearest approach, α Centauri will attain a maximum apparent magnitude of −0.86, comparable to present-day magnitude of Canopus, but it will still not surpass that of Sirius, which will brighten incrementally over the next 60,000 years, and will continue to be the brightest star as seen from Earth (other than the Sun) for the next 210,000 years.[99]

Stellar system

[edit]

Alpha Centauri is a triple star system, with its two main stars, A and B, together comprising a binary component. The AB designation, or older A×B, denotes the mass centre of a main binary system relative to companion star(s) in a multiple star system.[100] AB-C refers to the component of Proxima Centauri in relation to the central binary, being the distance between the centre of mass and the outlying companion. Because the distance between Proxima (C) and either of Alpha Centauri A or B is similar, the AB binary system is sometimes treated as a single gravitational object.[101]

Orbital properties

[edit]

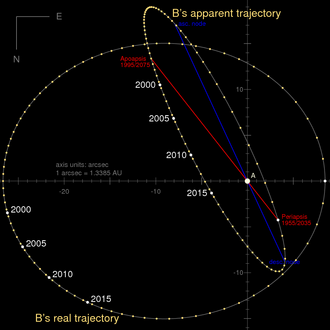

The A and B components of Alpha Centauri have an orbital period of 79.762 years. Their orbit is moderately eccentric, as it has an eccentricity of almost 0.52;[5] their closest approach or periastron is 11.2 AU (1.68×109 km), or about the distance between the Sun and Saturn; and their furthest separation or apastron is 35.6 AU (5.33×109 km), about the distance between the Sun and Pluto.[16] The most recent periastron was in August 1955 and the next will occur in May 2035; the most recent apastron was in May 1995 and will next occur in 2075.

Viewed from Earth, the apparent orbit of A and B means that their separation and position angle (PA) are in continuous change throughout their projected orbit. Observed stellar positions in 2019 are separated by 4.92 arcsec through the PA of 337.1°, increasing to 5.49 arcsec through 345.3° in 2020.[16] The closest recent approach was in February 2016, at 4.0 arcsec through the PA of 300°.[16][103] The observed maximum separation of these stars is about 22 arcsec, while the minimum distance is 1.7 arcsec.[69] The widest separation occurred during February 1976, and the next will be in January 2056.[16]

Alpha Centauri C is about 13,000 AU (0.21 ly; 1.9×1012 km) from Alpha Centauri AB, equivalent to about 5% of the distance between Alpha Centauri AB and the Sun.[17][59][68] Until 2017, measurements of its small speed and its trajectory were of too little accuracy and duration in years to determine whether it is bound to Alpha Centauri AB or unrelated.

Radial velocity measurements made in 2017 were precise enough to show that Proxima Centauri and Alpha Centauri AB are gravitationally bound.[17] The orbital period of Proxima Centauri is approximately 511000+41000

−30000 years, with an eccentricity of 0.5, much more eccentric than Mercury's. Proxima Centauri comes within 4100+700

−600 AU of AB at periastron, and its apastron occurs at 12300+200

−100 AU.[5]

Physical properties

[edit]

Asteroseismic studies, chromospheric activity, and stellar rotation (gyrochronology) are all consistent with the Alpha Centauri system being similar in age to, or slightly older than, the Sun.[104] Asteroseismic analyses that incorporate tight observational constraints on the stellar parameters for the Alpha Centauri stars have yielded age estimates of 4.85±0.5 Gyr,[105] 5.0±0.5 Gyr,[106] 5.2 ± 1.9 Gyr,[107] 6.4 Gyr,[108] and 6.52±0.3 Gyr.[109] Age estimates for the stars based on chromospheric activity (Calcium H & K emission) yield 4.4 ± 2.1 Gyr, whereas gyrochronology yields 5.0±0.3 Gyr.[104] Stellar evolution theory implies both stars are slightly older than the Sun at 5 to 6 billion years, as derived by their mass and spectral characteristics.[59][110]

From the orbital elements, the total mass of Alpha Centauri AB is about 2.0 M☉[g] – or twice that of the Sun.[69] The average individual stellar masses are about 1.08 M☉ and 0.91 M☉, respectively,[5] though slightly different masses have also been quoted in recent years, such as 1.14 M☉ and 0.92 M☉,[87] totaling 2.06 M☉. Alpha Centauri A and B have absolute magnitudes of +4.38 and +5.71, respectively.

Alpha Centauri AB System

[edit]

Alpha Centauri A

[edit]Alpha Centauri A, also known as Rigil Kentaurus, is the principal member, or primary, of the binary system. It is a solar-like main-sequence star with a similar yellowish colour,[112] whose stellar classification is spectral type G2-V;[3] it is about 10% more massive than the Sun,[105] with a radius about 22% larger.[113] When considered among the individual brightest stars in the night sky, it is the fourth-brightest at an apparent magnitude of +0.01,[2] being slightly fainter than Arcturus at an apparent magnitude of −0.05.

The type of magnetic activity on Alpha Centauri A is comparable to that of the Sun, showing coronal variability due to star spots, as modulated by the rotation of the star. However, since 2005 the activity level has fallen into a deep minimum that might be similar to the Sun's historical Maunder Minimum. Alternatively, it may have a very long stellar activity cycle and is slowly recovering from a minimum phase.[114]

Alpha Centauri B

[edit]Alpha Centauri B, also known as Toliman, is the secondary star of the binary system. It is a main-sequence star of spectral type K1-V, making it more an orange colour than Alpha Centauri A;[112] it has around 90% of the mass of the Sun and a 14% smaller diameter. Although it has a lower luminosity than A, Alpha Centauri B emits more energy in the X-ray band.[115] Its light curve varies on a short time scale, and there has been at least one observed flare.[115] It is more magnetically active than Alpha Centauri A, showing a cycle of 8.2±0.2 yr compared to 11 years for the Sun, and has about half the minimum-to-peak variation in coronal luminosity of the Sun.[114] This cycle was recently re-estimated based on more than 20 years of high-resolution spectroscopic observations of the CaIIH&K lines showing a cycle of 7.8±0.2 yr.[116] Alpha Centauri B has an apparent magnitude of +1.35, slightly dimmer than Mimosa.[46]

Alpha Centauri C

[edit]Alpha Centauri C, better known as Proxima Centauri, is a small main-sequence red dwarf of spectral class M6-Ve. It has an absolute magnitude of +15.60, over 20,000 times fainter than the Sun. Its mass is calculated to be 0.1221 M☉.[117] It is the closest star to the Sun but is too faint to be visible to the naked eye.[118]

Planetary system

[edit]The Alpha Centauri system as a whole has two confirmed planets, both of them around Proxima Centauri. While other planets have been claimed to exist around all of the stars, none of the discoveries have been confirmed.

Planets of Alpha Centauri A

[edit]| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (years) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (unconfirmed) | 90–150[22] M🜨 | ~2[21] | 2 – 3[22] | 0.4[22] | 16 – 163[22]° | 1.0–1.1[22] RJ |

In 2021, a candidate planet named Candidate 1 (or C1) was detected around Alpha Centauri A, thought to orbit at approximately 1.1 AU with a period of about one year, and to have a mass between that of Neptune and one-half that of Saturn, though it may be a dust disk or an artefact. The possibility of C1 being a background star has been ruled out.[119][20] If this candidate is confirmed, the temporary name C1 will most likely be replaced with the scientific designation Alpha Centauri Ab in accordance with current naming conventions.[120]

GO Cycle 1 observations are planned for the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to search for planets around Alpha Centauri A, as well as observations of Epsilon Muscae.[121] The coronographic observations, which occurred on July 26 and 27, 2023, were failures, though there are follow-up observations in March 2024.[122] Pre-launch estimates predicted that JWST will be able to find planets with a radius of 5 R🜨 at 1–3 AU. Multiple observations every 3–6 months could push the limit down to 3 R🜨.[123] Post-launch estimates based on observations of HIP 65426 b find that JWST will be able to find planets even closer to Alpha Centauri A and could find a 5 R🜨 planet at 0.5–2.5 AU.[124] Candidate 1 has an estimated radius between 3.3–11 R🜨[20] and orbits at 1.1 AU.

Observations with the James Webb Space Telescope in August 2024 uncovered a point source which might be an exoplanet at a separation of 2 astronomical units, believed to be the same object detected in 2021. This object is confirmed to be not a background object, and is unlikely to be an instrumental artifact, and therefore might be an exoplanet. It was not recovered and needs additional observations to be confirmed as a planet; there is a 52% chance it was not re-observed due to the orbital motion.[22][21] If it is an exoplanet, it should have a mass between 90 and 150 Earth masses, a radius between 1.0 and 1.1 RJ and a temperature of 225 K (−48 °C; −55 °F).[22]

Planets of Alpha Centauri B

[edit]The first claim of a planet around Alpha Centauri B was that of Alpha Centauri Bb in 2012, which was proposed to be an Earth-mass planet in a 3.2-day orbit.[125] This was refuted in 2015 when the apparent planet was shown to be an artefact of the way the radial velocity data was processed.[126][127][23]

A search for transits of planet Bb was conducted with the Hubble Space Telescope from 2013 to 2014. This search detected one potential transit-like event, which could be associated with a different planet with a radius around 0.92 R🜨. This planet would most likely orbit Alpha Centauri B with an orbital period of 20.4 days or less, with only a 5% chance of it having a longer orbit. The median of the likely orbits is 12.4 days. Its orbit would likely have an eccentricity of 0.24 or less.[128] It could have lakes of molten lava and would be far too close to Alpha Centauri B to harbour life.[129] If confirmed, this planet might be called Alpha Centauri Bc. However, the name has not been used in the literature, as it is not a claimed discovery.

Planets of Proxima Centauri

[edit]Proxima Centauri b or Alpha Centauri Cb is a terrestrial planet discovered in 2016 by astronomers at the European Southern Observatory (ESO). It has an estimated minimum mass of 1.17 M🜨 (Earth masses) and orbits approximately 0.049 AU from Proxima Centauri, placing it in the star's habitable zone.[130][131]

The discovery of Proxima Centauri c was formally published in 2020 and could be a super-Earth or mini-Neptune.[132][133] It has a mass of roughly 7 M🜨 and orbits about 1.49 AU from Proxima Centauri with a period of 1,928 days (5.28 yr).[134] In June 2020, a possible direct imaging detection of the planet hinted at the presence of a large ring system.[135] However, a 2022 study disputed the existence of this planet.[19] As of 2025[update], evidence for Proxima c remains inconclusive; observations with the NIRPS spectrograph were unable to confirm it, but found hints of a lower-amplitude signal with a similar period.[136]

A 2020 paper refining Proxima b's mass excludes the presence of extra companions with masses above 0.6 M🜨 at periods shorter than 50 days, but the authors detected a radial-velocity curve with a periodicity of 5.15 days, suggesting the presence of a planet with a mass of about 0.29 M🜨.[131] This planet, Proxima Centauri d, was detected in 2022[18][19] and later confirmed in 2025.[136]

Hypothetical planets

[edit]Additional planets may exist in the Alpha Centauri system, either orbiting Alpha Centauri A or Alpha Centauri B individually, or in large orbits around Alpha Centauri AB. Because both stars are fairly similar to the Sun (for example, in age and metallicity), astronomers have been especially interested in making detailed searches for planets in the Alpha Centauri system. Several established planet-hunting teams have used various radial velocity or star transit methods in their searches around these two bright stars.[137] All the observational studies have so far failed to find evidence for brown dwarfs or gas giants.[137][138]

In 2009, computer simulations showed that a planet might have been able to form near the inner edge of Alpha Centauri B's habitable zone, which extends from 0.5–0.9 AU from the star. Certain special assumptions, such as considering that the Alpha Centauri pair may have initially formed with a wider separation and later moved closer to each other (as might be possible if they formed in a dense star cluster), would permit an accretion-friendly environment farther from the star.[139] Bodies around Alpha Centauri A would be able to orbit at slightly farther distances due to its stronger gravity. In addition, the lack of any brown dwarfs or gas giants in close orbits around Alpha Centauri make the likelihood of terrestrial planets greater than otherwise.[140] A theoretical study indicates that a radial velocity analysis might detect a hypothetical planet of 1.8 M🜨 in Alpha Centauri B's habitable zone.[141]

Radial velocity measurements of Alpha Centauri B made with the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher spectrograph were sufficiently sensitive to detect a 4 M🜨 planet within the habitable zone of the star (i.e. with an orbital period P = 200 days), but no planets were detected.[125]

Current estimates place the probability of finding an Earth-like planet around Alpha Centauri at roughly 75%.[142] The observational thresholds for planet detection in the habitable zones by the radial velocity method are currently (2017) estimated to be about 53 M🜨 for Alpha Centauri A, 8.4 M🜨 for Alpha Centauri B, and 0.47 M🜨 for Proxima Centauri.[143]

Early computer-generated models of planetary formation predicted the existence of terrestrial planets around both Alpha Centauri A and B,[141][144] but most recent numerical investigations have shown that the gravitational pull of the companion star renders the accretion of planets difficult.[139][145] Despite these difficulties, given the similarities to the Sun in spectral types, star type, age and probable stability of the orbits, it has been suggested that this stellar system could hold one of the best possibilities for harbouring extraterrestrial life on a potential planet.[6][140][146][144]

In the Solar System, it was once thought that Jupiter and Saturn were probably crucial in perturbing comets into the inner Solar System, providing the inner planets with a source of water and various other ices.[147] However, since isotope measurements of the deuterium to hydrogen (D/H) ratio in comets Halley, Hyakutake, Hale–Bopp, 2002T7, and Tuttle yield values approximately twice that of Earth's oceanic water, more recent models and research predict that less than 10% of Earth's water was supplied from comets. In the α Centauri system, Proxima Centauri may have influenced the planetary disk as the α Centauri system was forming, enriching the area around Alpha Centauri with volatile materials.[148] This would be discounted if, for example, α Centauri B happened to have gas giants orbiting α Centauri A (or vice versa), or if α Centauri A and B themselves were able to perturb comets into each other's inner systems, as Jupiter and Saturn presumably have done in the Solar System.[147] Such icy bodies probably also reside in Oort clouds of other planetary systems. When they are influenced gravitationally by either the gas giants or disruptions by passing nearby stars, many of these icy bodies then travel star-wards.[147] Such ideas also apply to the close approach of Alpha Centauri or other stars to the Solar system, when, in the distant future, the Oort Cloud might be disrupted enough to increase the number of active comets.[97]

To be in the habitable zone, a planet around Alpha Centauri A would have an orbital radius of between about 1.2 and 2.1 AU so as to have similar planetary temperatures and conditions for liquid water to exist.[149] For the slightly less luminous and cooler α Centauri B, the habitable zone is between about 0.7 and 1.2 AU.[149]

With the goal of finding evidence of such planets, both Proxima Centauri and α Centauri AB were among the listed "Tier-1" target stars for NASA's Space Interferometry Mission (S.I.M.). Detecting planets as small as three Earth-masses or smaller within two AU of a "Tier-1" target would have been possible with this new instrument.[150] The S.I.M. mission, however, was cancelled due to financial issues in 2010.[151]

Circumstellar discs

[edit]Based on observations between 2007 and 2012, a study found a slight excess of emissions in the 24 μm (mid/far-infrared) band surrounding α Centauri AB, which may be interpreted as evidence for a sparse circumstellar disc or dense interplanetary dust.[152] The total mass was estimated to be between 10−7 to 10−6 the mass of the Moon, or 10–100 times the mass of the Solar System's zodiacal cloud.[152] If such a disc existed around both stars, α Centauri A's disc would likely be stable to 2.8 AU, and α Centauri B's would likely be stable to 2.5 AU [152] This would put A's disc entirely within the frost line, and a small part of B's outer disc just outside.[152]

View from this system

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2023) |

The sky from α Centauri AB would appear much as it does from the Earth, except that Centaurus's brightest star, being α Centauri AB itself, would be absent from the constellation. The Sun would appear as a white star of apparent magnitude +0.5,[153] roughly the same as the average brightness of Betelgeuse from Earth. It would be at the antipodal point of α Centauri AB's current right ascension and declination, at 02h 39m 36s +60° 50′ 02.308″ (2000), in eastern Cassiopeia, easily outshining all the rest of the stars in the constellation. With the placement of the Sun east of the magnitude 3.4 star Epsilon Cassiopeiae, nearly in front of the Heart Nebula, the "W" line of stars of Cassiopeia would have a "/W" shape.[154]

Other nearby stars' placements may be affected somewhat drastically. Sirius, at 9.2 light years away from the system, would still be the brightest star in the night sky, with a magnitude of -1.2, but would be located in Orion less than a degree away from Betelgeuse. Procyon, which would also be at a slightly further distance than from the Sun, would move to outshine Pollux in the middle of Gemini.

A planet around either α Centauri A or B would see the other star as a very bright secondary. For example, an Earth-like planet at 1.25 AU from α Cen A (with a revolution period of 1.34 years) would get Sun-like illumination from its primary, and α Cen B would appear 5.7–8.6 magnitudes dimmer (−21.0 to −18.2), 190–2,700 times dimmer than α Cen A but still 150–2,100 times brighter than the full Moon. Conversely, an Earth-like planet at 0.71 AU from α Cen B (with a revolution period of 0.63 years) would get nearly Sun-like illumination from its primary, and α Cen A would appear 4.6–7.3 magnitudes dimmer (−22.1 to −19.4), 70 to 840 times dimmer than α Cen B but still 470–5,700 times brighter than the full Moon.

Proxima Centauri would appear dim as one of many stars, being magnitude 4.5 at its current distance, and magnitude 2.6 at periastron.[155]

Future exploration

[edit]

Alpha Centauri is a first target for crewed or robotic interstellar exploration. Using current spacecraft technologies, crossing the distance between the Sun and Alpha Centauri would take several millennia, though the possibility of nuclear pulse propulsion or laser light sail technology, as considered in the Breakthrough Starshot program, could make the journey to Alpha Centauri in 20 years.[156][157][158] An objective of such a mission would be to make a fly-by of, and possibly photograph, planets that might exist in the system.[159][160] The existence of Proxima Centauri b, announced by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in August 2016, would be a target for the Starshot program.[159][161]

NASA released a mission concept in 2017 that would send a spacecraft to Alpha Centauri in 2069, scheduled to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the first crewed lunar landing in 1969, Apollo 11. Even at 10% of the speed of light (about 108 million km/h), which NASA experts say may be possible, it would take a spacecraft 44 years to reach the system, by the year 2113, and would take another 4 years for a signal, by the year 2117 to reach Earth. The concept received no further funding or development.[162][163]

In culture

[edit]Alpha Centauri has been recognized and associated throughout history, particularly in the Southern Hemisphere. Polynesians have been using Alpha Centauri for their star navigation and have called it Kamailehope. In the Ngarrindjeri culture of Australia, Alpha Centauri represents with Beta Centauri two sharks chasing a stingray, the Southern Cross, and in Incan culture it with Beta Centauri form the eyes of a llama-shaped dark constellation embedded in the band of stars that the visible Milky Way forms in the sky. In ancient Egypt it was also revered and in China it is known as part of the South Gate asterism.[164]

The Sagan Planet Walk in Ithaca, New York, is a walkable scale model of the solar system. An obelisk representing the scaled position of Alpha Centauri has been added at ʻImiloa Astronomy Center in Hawaii.[165]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Proxima Centauri is gravitationally bound to the α Centauri system, but for practical and historical reasons it is described in detail in its own article.

- ^ Semi-major axis in AU = semimajor axis in seconds/ parallax = 17.493″/0.75081 = 23.299 AU; as the eccentricity is 0.52, the distance fluctuates between 48% and 152% of that, roughly from 11 AU to 35 AU.

- ^ Spellings include Rigjl Kentaurus,[32] Portuguese Riguel Kentaurus,[33][34]

- ^ This is calculated for a fixed latitude by knowing the star's declination (δ) using the formulae (90°+ δ). α Centauri's declination is −60° 50′, so the observed latitude where the star is circumpolar will be south of −29° 10′ South or 29°. Similarly, the place where Alpha Centauri never rises for northern observers is north of the latitude (90°+ δ) N or +29° North.

- ^ Weighted parallax based on parallaxes from van Altena et al. (1995) and Söderhjelm (1999).

- ^ Proper motions are expressed in smaller angular units than arcsec, being measured in milliarcsec (mas.) (thousandths of an arcsec). Negative values for proper motion in RA indicate the sky motion is from east to west, and in declination north to south.

- ^ – see formula in standard gravitational parameter article.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600.

- ^ a b c d e Ducati, J. R. (2002). Catalogue of Stellar Photometry in Johnson's 11 color system. VizieR Online Data Catalog (Report). CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues. Vol. 2237. Bibcode:2002yCat.2237....0D.

- ^ a b c Torres, C.A.O.; Quast, G.R.; da Silva, L.; de la Reza, R.; Melo, C.H.F.; Sterzik, M. (2006). "Search for associations containing young stars (SACY)". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 460 (3): 695–708. arXiv:astro-ph/0609258. Bibcode:2006A&A...460..695T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20065602. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 16080025.

- ^ a b Valenti, Jeff A.; Fischer, Debra A. (2005). "Spectroscopic properties of cool stars (SPOCS) I. 1040 F, G, and K dwarfs from Keck, Lick, and AAT planet search programs". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 159 (1): 141–166. Bibcode:2005ApJS..159..141V. doi:10.1086/430500. ISSN 0067-0049.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Akeson, Rachel; Beichman, Charles; Kervella, Pierre; Fomalont, Edward; Benedict, G. Fritz (20 April 2021). "Precision millimeter astrometry of the α Centauri AB system". The Astronomical Journal. 162 (1): 14. arXiv:2104.10086. Bibcode:2021AJ....162...14A. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/abfaff. S2CID 233307418.

- ^ a b c Wiegert, P.A.; Holman, M.J. (1997). "The stability of planets in the Alpha Centauri system". The Astronomical Journal. 113: 1445–1450. arXiv:astro-ph/9609106. Bibcode:1997AJ....113.1445W. doi:10.1086/118360. S2CID 18969130.

- ^ a b Gilli, G.; Israelian, G.; Ecuvillon, A.; Santos, N.C.; Mayor, M. (2006). "Abundances of refractory elements in the atmospheres of stars with extrasolar planets". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 449 (2): 723–736. arXiv:astro-ph/0512219. Bibcode:2006A&A...449..723G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053850. S2CID 13039037. libcode 2005astro.ph.12219G.

- ^ a b c d Soubiran, C.; Creevey, O. L.; Lagarde, N.; Brouillet, N.; Jofré, P.; Casamiquela, L.; Heiter, U.; Aguilera-Gómez, C.; Vitali, S.; Worley, C.; de Brito Silva, D. (1 February 2024). "Gaia FGK benchmark stars: Fundamental Teff and log g of the third version". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 682: A145. arXiv:2310.11302. Bibcode:2024A&A...682A.145S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202347136. ISSN 0004-6361. Alpha Centauri's database entry at VizieR.

- ^ Huber, Daniel; Zwintz, Konstanze; et al. (the BRITE team) (July 2020). "Solar-like oscillations: Lessons learned & first results from TESS". Stars and Their Variability Observed from Space: 457. arXiv:2007.02170. Bibcode:2020svos.conf..457H.

- ^ Bazot, M.; et al. (2007). "Asteroseismology of α Centauri A. Evidence of rotational splitting". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 470 (1): 295–302. arXiv:0706.1682. Bibcode:2007A&A...470..295B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20065694. S2CID 118785894.

- ^ a b Joyce, M.; Chaboyer, B. (2018). "Classically and asteroseismically constrained 1D stellar evolution models of α Centauri A and B using empirical mixing length calibrations". The Astrophysical Journal. 864 (1): 99. arXiv:1806.07567. Bibcode:2018ApJ...864...99J. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aad464. S2CID 119482849.

- ^ Dumusque, Xavier (December 2014). "Deriving Stellar Inclination of Slow Rotators Using Stellar Activity". The Astrophysical Journal. 796 (2): 133. arXiv:1409.3593. Bibcode:2014ApJ...796..133D. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/796/2/133. S2CID 119184190.

- ^ Raassen, A.J.J.; Ness, J.-U.; Mewe, R.; van der Meer, R.L.J.; Burwitz, V.; Kaastran, J.S. (2003). "Chandra-LETGS X-ray observation of α Centauri: A nearby (G2V + K1V) binary system". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 400 (2): 671–678. Bibcode:2003A&A...400..671R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20021899.

- ^ a b IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN) (Report). International Astronomical Union. 2016. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Kervella, Pierre; Thevenin, Frederic (15 March 2003). "A family portrait of the Alpha Centauri system" (Press release). European Southern Observatory. p. 5. Bibcode:2003eso..pres...39. eso0307, PR 05/03.

- ^ a b c d e f

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Hartkopf, W.; Mason, D. M. (2008). "Sixth Catalog of Orbits of Visual Binaries". U.S. Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Hartkopf, W.; Mason, D. M. (2008). "Sixth Catalog of Orbits of Visual Binaries". U.S. Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- ^ a b c Kervella, P.; Thévenin, F.; Lovis, C. (January 2017). "Proxima's orbit around α Centauri". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 598: L7. arXiv:1611.03495. Bibcode:2017A&A...598L...7K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629930. S2CID 50867264.

- ^ a b Faria, J. P.; Suárez Mascareño, A.; et al. (4 January 2022). "A candidate short-period sub-Earth orbiting Proxima Centauri" (PDF). Astronomy & Astrophysics. 658. European Southern Observatory: 17. arXiv:2202.05188. Bibcode:2022A&A...658A.115F. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202142337.

- ^ a b c Artigau, Étienne; Cadieux, Charles; Cook, Neil J.; Doyon, René; Vandal, Thomas; Donati, Jean-François; Moutou, Claire; Delfosse, Xavier; Fouqué, Pascal; Martioli, Eder; Bouchy, François; Parsons, Jasmine; Carmona, Andres; Dumusque, Xavier; Astudillo-Defru, Nicola; Bonfils, Xavier; Mignon, Lucille (2022). "Line-by-line Velocity Measurements: An Outlier-resistant Method for Precision Velocimetry". The Astronomical Journal. 164 (3): 84. arXiv:2207.13524. Bibcode:2022AJ....164...84A. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac7ce6.

- ^ a b c Wagner, K.; Boehle, A.; Pathak, P.; Kasper, M.; Arsenault, R.; Jakob, G.; et al. (10 February 2021). "Imaging low-mass planets within the habitable zone of α Centauri". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 922. arXiv:2102.05159. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12..922W. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21176-6. PMC 7876126. PMID 33568657. Kevin Wagner's (lead author of paper?) video of discovery

- ^ a b c Sanghi, Aniket; et al. (August 2025). "Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. II. Binary Star Modeling, Planet and Exozodi Search, and Sensitivity Analysis". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. arXiv:2508.03812. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/adf53e.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Beichman, Charles; et al. (August 2025). "Worlds Next Door: A Candidate Giant Planet Imaged in the Habitable Zone of α Cen A. I. Observations, Orbital and Physical Properties, and Exozodi Upper Limits". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. arXiv:2508.03814. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/adf53f.

- ^ a b Rajpaul, Vinesh; Aigrain, Suzanne; Roberts, Stephen J. (19 October 2015). "Ghost in the time series: No planet for alpha Cen B". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 456 (1): L6 – L10. arXiv:1510.05598. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.456L...6R. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slv164. S2CID 119294717.

- ^ "Alpha Centauri, the star system closest to our sun". 16 April 2023.

- ^ a b c Kunitzsch, Paul; Smart, Tim (2006). A Dictionary of Modern Star Names: A short guide to 254 star names and their derivations. Sky Pub. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-931559-44-7.

- ^ Davis Jr, George R. (October 1944). "The pronunciations, derivations, and meanings of a selected list of star names". Popular Astronomy. Vol. 52, no. 3. p. 16. Bibcode:1944PA.....52....8D.

- ^ Savage-Smith, Emilie (1985). Islamicate Celestial Globes: Their history, construction, and use (PDF). Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology. Vol. 46. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- ^ a b Allen, R.H. Star Names and their Meanings.

- ^ Baily, Francis (1843). "The Catalogues of Ptolemy, Ulugh Beigh, Tycho Brahe, Halley, Hevelius, deduced from the best authorities". Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society. 13: 1. Bibcode:1843MmRAS..13....1B.

With various notes and corrections, and a preface to each catalogue. To which is added the synonym of each star, in the catalogues or Flamsteed of Lacaille, as far as the same can be ascertained.

- ^ Rees, Martin (17 September 2012). Universe: The definitive visual guide. DK Publishing. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-4654-1114-3.

- ^ Kaler, James B. (7 May 2006). The Hundred Greatest Stars. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-387-21625-6.

- ^ Hyde, T. (1665). "Ulugh Beighi Tabulae Stellarum Fixarum". Tabulae Long. ac Lat. Stellarum Fixarum ex Observatione Ulugh Beighi. Oxford, UK. pp. 142, 67.

- ^ da Silva Oliveira, R. Crux Australis: o Cruzeiro do Sul. Archived from the original on 6 December 2013.

- ^ Artigos. Planetario Movel Inflavel AsterDomus (in Latin).

- ^ Lane, Edward William (ed.). "zalim dh" ظليم ذ. An Arabic–English Lexicon.

- ^ Kunitzsch, P. (1976). "Naturwissenschaft und Philologie: Die arabischen Elemente in der Nomenklatur und Terminologie der Himmelskunde". Die Sterne. 52: 218. Bibcode:1976Stern..52..218K. doi:10.1515/islm.1975.52.2.263. S2CID 162297139.

- ^ Hermelink, H.; Kunitzsch, Paul (1961). "Reviewed work: Arabische Sternnamen in Europa, Paul Kunitzsch". Journal of the American Oriental Society (book review). 81 (3): 309–312. doi:10.2307/595661. JSTOR 595661.

- ^ ibn Muḥammad al-Fargānī, Aḥmad; Golius, Jakob (1669). Muhammedis fil. Ketiri Ferganensis, qui vulgo Alfraganus dicitur, Elementa astronomica, Arabicè & Latinè. Cum notis ad res exoticas sive Orientales, quae in iis occurrunt [Muhammedis son of Ketiri Ferganensis, who is commonly called al-Fraganus, Astronomical Elements, Arabic and Latin. With notes to the exotic or oriental things that occur in them.]. Opera Jacobi Golii (in Latin). apud Johannem Jansonium à Waasberge, & viduam Elizei Weyerstraet. p. 76.

- ^ Schaaf, Fred (31 March 2008). The Brightest Stars: Discovering the universe through the sky's most brilliant stars. Wiley. p. 122. Bibcode:2008bsdu.book.....S. ISBN 978-0-470-24917-8.

- ^ Innes, R.T.A. (October 1915). "A faint star of large proper motion". Circular of the Union Observatory Johannesburg. 30: 235–236. Bibcode:1915CiUO...30..235I.

- ^ Innes, R.T.A. (September 1917). "Parallax of the faint proper motion star near alpha of Centaurus. 1900. R.A. 14h22m55s-0s 6t. Dec-62° 15'2 0'8 t". Circular of the Union Observatory Johannesburg. 40: 331–336. Bibcode:1917CiUO...40..331I.

- ^ Stevenson, Angus, ed. (2010). "Proxima Centauri". Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 1431. ISBN 978-0-19-957112-3.

- ^ Alden, Harold L. (1928). "Alpha and Proxima Centauri". Astronomical Journal. 39 (913): 20–23. Bibcode:1928AJ.....39...20A. doi:10.1086/104871.

- ^ Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names (PDF) (Report). International Astronomical Union. October 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ WG Triennial Report (PDF). Star Names (Report). IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN). International Astronomical Union. 2015–2018. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ a b "Naming Stars". International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ IAU Catalog of Star Names (Report). International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ^ Burritt, Elijah Hinsdale (1850). Atlas: Designed to illustrate the geography of the heavens. F. J. Huntington.

- ^ (in Chinese) [ AEEA (Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy) 天文教育資訊網 2006 年 6 月 27 日]

- ^ a b Hamacher, Duane W.; Frew, David J. (2010). "An Aboriginal Australian Record of the Great Eruption of Eta Carinae". Journal of Astronomical History & Heritage. 13 (3): 220–234. arXiv:1010.4610. Bibcode:2010JAHH...13..220H. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1440-2807.2010.03.06. S2CID 118454721.

- ^ Stanbridge, W. M. (1857). "On the Astronomy and Mythology of the Aboriginies of Victoria". Transactions Philosophical Institute Victoria. 2: 137–140.

- ^ a b Moore, Patrick, ed. (2002). Astronomy Encyclopedia. Philip's. ISBN 978-0-540-07863-9.[dead link]

- ^ van Zyl, Johannes Ebenhaezer (1996). Unveiling the Universe: An introduction to astronomy. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-76023-8.

- ^ a b c d Hartung, E.J.; Frew, David; Malin, David (1994). Astronomical Objects for Southern Telescopes. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Norton, A.P.; Ridpath, Ed. I. (1986). Norton's 2000.0: Star Atlas and Reference Handbook. Longman Scientific and Technical. pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b Hartung, E.J.; Frew, D.; Malin, D. (1994). Astronomical Objects for Southern Telescopes. Melbourne University Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-522-84553-2.

- ^ Mitton, Jacquelin (1993). The Penguin Dictionary of Astronomy. Penguin Books. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-14-051226-7.

- ^ James, Andrew. "Culmination Times". The Constellations, Part 2. Southern Astronomical Delights (southastrodel.com). Sydney, New South Wales. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ^ a b c Matthews, R.A.J.; Gilmore, Gerard (1993). "Is Proxima really in orbit about α Cen A/B ?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 261: L5 – L7. Bibcode:1993MNRAS.261L...5M. doi:10.1093/mnras/261.1.l5.

- ^ Benedict, G. Fritz; McArthur, Barbara; Nelan, E.; Story, D.; Whipple, A.L.; Shelus, P.J.; et al. (1998). Donahue, R.A.; Bookbinder, J.A. (eds.). Proxima Centauri: Time-resolved astrometry of a flare site using HST fine guidance sensor 3. The Tenth Cambridge Workshop on Cool Stars, Stellar Systems and the Sun. ASP Conference Series. Vol. 154. p. 1212. Bibcode:1998ASPC..154.1212B.

- ^ Page, A.A. (1982). "Mount Tamborine Observatory". International Amateur-Professional Photoelectric Photometry Communication. 10: 26. Bibcode:1982IAPPP..10...26P.

- ^ "Light curve generator (LCG)". American Association of Variable Star Observers (aavso.org). Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ^ Ptolemaeus, Claudius (1984). Ptolemy's Almagest (PDF). Translated by Toomer, G. J. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. p. 368, note 136. ISBN 978-0-7156-1588-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2017.[dead link]

- ^ Knobel, Edward B. (1917). "On Frederick de Houtman's Catalogue of Southern Stars, and the origin of the southern constellations". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 77 (5): 414–432 [416]. Bibcode:1917MNRAS..77..414K. doi:10.1093/mnras/77.5.414.

- ^ Kameswara-Rao, N.; Vagiswari, A.; Louis, C. (1984). "Father J. Richaud and early telescope observations in India". Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India. 12: 81. Bibcode:1984BASI...12...81K.

- ^ a b Pannekoek, Anton (1989) [1961]. A History of Astronomy (reprint ed.). Dover. pp. 345–346. ISBN 978-0-486-65994-7.

- ^ Herschel, J.F.W. (1847). Results of astronomical observations made during the years 1834, 5, 6, 7, 8 at the Cape of Good Hope; being the completion of a telescopic survey of the whole surface of the visible heavens, commenced in 1825. Smith, Elder and Co, London. Bibcode:1847raom.book.....H.

- ^ a b Kamper, K. W.; Wesselink, A. J. (1978). "Alpha and Proxima Centauri". Astronomical Journal. 83: 1653. Bibcode:1978AJ.....83.1653K. doi:10.1086/112378.

- ^ a b c d Aitken, R.G. (1961). The Binary Stars. Dover. pp. 235–237.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Sixth Catalogue of Orbits of Visual Binary Stars: Ephemeris (2008)". U.S. Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Sixth Catalogue of Orbits of Visual Binary Stars: Ephemeris (2008)". U.S. Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 13 August 2008.

- ^ Linsky, Jeffrey L.; Redfield, Seth; Tilipman, Dennis (November 2019). "The interface between the outer heliosphere and the inner local ISM: Morphology of the local interstellar cloud, its hydrogen hole, Strömgren shells, and 60Fe accretion". The Astrophysical Journal. 886 (1): 19. arXiv:1910.01243. Bibcode:2019ApJ...886...41L. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ab498a. S2CID 203642080. 41.

- ^ Boffin, Henri M.J.; Pourbaix, D.; Mužić, K.; Ivanov, V.D.; Kurtev, R.; Beletsky, Y.; et al. (4 December 2013). "Possible astrometric discovery of a substellar companion to the closest binary brown dwarf system WISE J104915.57–531906.1". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 561: L4. arXiv:1312.1303. Bibcode:2014A&A...561L...4B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201322975. S2CID 33043358.

- ^ a b Henderson, H. (1839). "On the parallax of α Centauri". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 4 (19): 168–169. Bibcode:1839MNRAS...4..168H. doi:10.1093/mnras/4.19.168.

- ^ Henderson, T. (1842). "The parallax of α Centauri, deduced from Mr. Maclear's observations at the Cape of Good Hope, in the years 1839 and 1840". Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society. 12: 370–371. Bibcode:1842MmRAS..12..329H.

- ^ Maclear, T. (1851). "Determination of the Parallax of α 1 and α2 Centauri, from Observations made at the Royal Observatory, Cape of Good Hope, in the Years 1842-3-4 and 1848". Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society. 20: 98. Bibcode:1851MmRAS..20...70M.

- ^ Moesta, C. G. (1868). "Bestimmung der Parallaxe von α und β Centauri" [Determining the parallax of α and β Centauri]. Astronomische Nachrichten (in German). 71 (8): 117–118. Bibcode:1868AN.....71..113M. doi:10.1002/asna.18680710802.

- ^ Gill, David; Elkin, W. L. (1885). "Heliometer-Determinations of Stellar Parallax in the Southern Hemisphere". Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society. 48: 188. Bibcode:1885MmRAS..48....1G.

- ^ Roberts, Alex W. (1895). "Parallax of α Centauri from Meridian Observations 1879–1881". Astronomische Nachrichten. 139 (12): 189–190. Bibcode:1895AN....139..177R. doi:10.1002/asna.18961391202.

- ^ Woolley, R.; Epps, E. A.; Penston, M. J.; Pocock, S. B. (1970). "Woolley 559". Catalogue of Stars within 25 Parsecs of the Sun. 5: ill. Bibcode:1970ROAn....5.....W. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Gliese, W.; Jahreiß, H. (1991). "Gl 559". Preliminary Version of the Third Catalogue of Nearby Stars. Astronomische Rechen-Institut. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ van Altena, W.F.; Lee, J.T.; Hoffleit, E.D. (1995). "GCTP 3309". The General Catalogue of Trigonometric Stellar Parallaxes (Report) (4th ed.). Yale University Observatory. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Perryman; et al. (1997). HIP 71683 (Report). The Hipparcos and Tycho Catalogues. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Perryman; et al. (1997). HIP 71681 (Report). The Hipparcos and Tycho Catalogues. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Söderhjelm, Staffan (1999). "Visual binary orbits and masses post Hipparcos". HIP 71683 (Report). Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ van Leeuwen, Floor (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". HIP 71683 (Report).

- ^ van Leeuwen, Floor (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". HIP 71681 (Report).

- ^ a b The one hundred nearest star systems (Report). Research Consortium on Nearby Stars. Georgia State University. 7 September 2007. Archived from the original on 12 November 2007. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ "High-Proper Motion Stars (2004)". Hipparcos mission website. ESA.

- ^ Aristotle (2004). "De Caelo" [On the Heavens]. Book II Part 11. Archived from the original on 23 August 2008. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

- ^

Berry, Arthur (1898). A Short History of Astronomy. London: John Murray. p. 255 – via Wikisource.

Berry, Arthur (1898). A Short History of Astronomy. London: John Murray. p. 255 – via Wikisource.

- ^ "Henderson, Thomas [FRS]". Astronomical Society of South Africa. 2008. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012.

- ^ Pannekoek, Anton (1989). A History of Astronomy. Courier Corporation. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-486-65994-7.

- ^ Maclear, M. (1851). "Determination of parallax of α1 and α2 Centauri". Astronomische Nachrichten. 32 (16): 243–244. Bibcode:1851MNRAS..11..131M. doi:10.1002/asna.18510321606.

- ^ N. L., de la Caillé (1976). Travels at the Cape, 1751–1753: An annotated translation of journal historique du voyage fait au Cap de Bonne-Espérance. Translated by Raven-Hart, R. Cape Town. ISBN 978-0-86961-068-8.

- ^ a b c Kervella, Pierre; et al. (2016). "Close stellar conjunctions of α Centauri A and B until 2050 An mK = 7.8 star may enter the Einstein ring of α Cen A". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 594 (107): A107. arXiv:1610.06079. Bibcode:2016A&A...594A.107K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629201. S2CID 55865290.

- ^ Marshall Eubanks, T.; Hein, Andreas M.; Lingam, Manasvi; Hibberd, Adam; Fries, Dan; Perakis, Nikolaos; et al. (2021). "Interstellar objects in the Solar System: 1. Isotropic kinematics from the Gaia early data release 3". arXiv:2103.03289 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ a b Matthews, R.A.J. (1994). "The close approach of stars in the Solar neighbourhood". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 35: 1–8. Bibcode:1994QJRAS..35....1M.

- ^ C.A.L., Bailer-Jones (2015). "Close encounters of the stellar kind". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 575: A35 – A48. arXiv:1412.3648. Bibcode:2015A&A...575A..35B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201425221. S2CID 59039482.

- ^ "[no title cited]". Sky and Telescope. April 1998. p. 60.

Calculation based on computations from HIPPARCOS data.

- ^ Heintz, W. D. (1978). Double Stars. D. Reidel. p. 19. ISBN 978-90-277-0885-4.[dead link]

- ^ Worley, C.E.; Douglass, G.G. (1996). Washington Visual Double Star Catalog, 1996.0 (WDS). United States Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 22 April 2000.

- ^ Pourbaix, D.; et al. (2002). "Constraining the difference in convective blueshift between the components of alpha Centauri with precise radial velocities". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 386 (1): 280–285. arXiv:astro-ph/0202400. Bibcode:2002A&A...386..280P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020287. S2CID 14308791.

- ^ James, Andrew (11 March 2008). "ALPHA CENTAURI: 6". southastrodel.com. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ a b Mamajek, E.E.; Hillenbrand, L.A. (2008). "Improved age estimation for Solar-type dwarfs using activity-rotation diagnostics". Astrophysical Journal. 687 (2): 1264–1293. arXiv:0807.1686. Bibcode:2008ApJ...687.1264M. doi:10.1086/591785. S2CID 27151456.

- ^ a b Thévenin, F.; Provost, J.; Morel, P.; Berthomieu, G.; Bouchy, F.; Carrier, F. (2002). "Asteroseismology and calibration of alpha Cen binary system". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 392: L9. arXiv:astro-ph/0206283. Bibcode:2002A&A...392L...9T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20021074. S2CID 17293259.

- ^ Bazot, M.; Bourguignon, S.; Christensen-Dalsgaard, J. (2012). "A Bayesian approach to the modelling of alpha Cen A". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 427 (3): 1847–1866. arXiv:1209.0222. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.427.1847B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21818.x. S2CID 118414505.

- ^ Miglio, A.; Montalbán, J. (2005). "Constraining fundamental stellar parameters using seismology. Application to α Centauri AB". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 441 (2): 615–629. arXiv:astro-ph/0505537. Bibcode:2005A&A...441..615M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20052988. S2CID 119078808.

- ^ Thoul, A.; Scuflaire, R.; Noels, A.; Vatovez, B.; Briquet, M.; Dupret, M.-A.; Montalban, J. (2003). "A new seismic analysis of alpha Centauri". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 402: 293–297. arXiv:astro-ph/0303467. Bibcode:2003A&A...402..293T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20030244. S2CID 15886763.

- ^ Eggenberger, P.; Charbonnel, C.; Talon, S.; Meynet, G.; Maeder, A.; Carrier, F.; Bourban, G. (2004). "Analysis of α Centauri AB including seismic constraints". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 417: 235–246. arXiv:astro-ph/0401606. Bibcode:2004A&A...417..235E. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20034203. S2CID 119487043.

- ^ Kim, Y-C. (1999). "Standard stellar models; alpha Cen A and B". Journal of the Korean Astronomical Society. 32 (2): 119. Bibcode:1999JKAS...32..119K.

- ^ "Best image of Alpha Centauri A and B". spacetelescope.org. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ a b "The colour of stars". Australia Telescope, Outreach and Education. Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation. 21 December 2004. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ Kervella, P.; Bigot, L.; Gallenne, A.; Thévenin, F. (January 2017). "The radii and limb darkenings of α Centauri A and B. Interferometric measurements with VLTI/PIONIER". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 597: A137. arXiv:1610.06185. Bibcode:2017A&A...597A.137K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629505. S2CID 55597767.

- ^ a b Ayres, Thomas R. (March 2014). "The Ups and Downs of α Centauri". The Astronomical Journal. 147 (3): 12. arXiv:1401.0847. Bibcode:2014AJ....147...59A. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/147/3/59. S2CID 117715969. 59.

- ^ a b Robrade, J.; Schmitt, J. H. M. M.; Favata, F. (2005). "X-rays from α Centauri – The darkening of the solar twin". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 442 (1): 315–321. arXiv:astro-ph/0508260. Bibcode:2005A&A...442..315R. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053314. S2CID 119120.

- ^ Cretignier, M.; Hara, N.; Pietrow, A.G.M. (2024). "Stellar surface information from the Ca II H&K lines - II. Defining better activity proxies". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 535 (1): 2562–2584. arXiv:astro-ph/0508260. Bibcode:2024MNRAS.535.2562C. doi:10.1093/mnras/stae2508. S2CID 119120.

- ^ Kervella, P.; Thévenin, F.; Lovis, C. (2017). "Proxima's orbit around α Centauri". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 598: L7. arXiv:1611.03495. Bibcode:2017A&A...598L...7K. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201629930. ISSN 0004-6361. S2CID 50867264.

- ^ "Proxima Centauri UV flux distribution". The Astronomical Data Centre. ESA. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- ^ Sample, Ian (10 February 2021). "Astronomers' hopes raised by glimpse of possible new planet?". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ "Naming of Exoplanets". International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on 10 January 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ "1618 Program Information". www.stsci.edu. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ "Visit Information". www.stsci.edu. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ Beichman, Charles; Ygouf, Marie; Llop Sayson, Jorge; Mawet, Dimitri; Yung, Yuk; Choquet, Elodie; Kervella, Pierre; Boccaletti, Anthony; Belikov, Ruslan; Lissauer, Jack J.; Quarles, Billy; Lagage, Pierre-Olivier; Dicken, Daniel; Hu, Renyu; Mennesson, Bertrand (1 January 2020). "Searching for Planets Orbiting α Cen A with the James Webb Space Telescope". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 132 (1007): 015002. arXiv:1910.09709. Bibcode:2020PASP..132a5002B. doi:10.1088/1538-3873/ab5066. ISSN 0004-6280. S2CID 204823856.

- ^ Carter, Aarynn L.; Hinkley, Sasha; Kammerer, Jens; Skemer, Andrew; Biller, Beth A.; Leisenring, Jarron M.; Millar-Blanchaer, Maxwell A.; Petrus, Simon; Stone, Jordan M.; Ward-Duong, Kimberly; Wang, Jason J.; Girard, Julien H.; Hines, Dean C.; Perrin, Marshall D.; Pueyo, Laurent (2023). "The JWST Early Release Science Program for Direct Observations of Exoplanetary Systems I: High-contrast Imaging of the Exoplanet HIP 65426 b from 2 to 16 μm". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 951 (1): L20. arXiv:2208.14990. Bibcode:2023ApJ...951L..20C. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/acd93e.

- ^ a b Dumusque, X.; Pepe, F.; Lovis, C.; Ségransan, D.; Sahlmann, J.; Benz, W.; Bouchy, F.; Mayor, M.; Queloz, D.; Santos, N.; Udry, S. (17 October 2012). "An Earth mass planet orbiting Alpha Centauri B" (PDF). Nature. 490 (7423): 207–211. Bibcode:2012Natur.491..207D. doi:10.1038/nature11572. PMID 23075844. S2CID 1110271. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ^ Wenz, John (29 October 2015). "It turns out the closest exoplanet to us doesn't actually exist". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ "Poof! The planet closest to our Solar system just vanished". National Geographic News. 29 October 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Demory, Brice-Olivier; Ehrenreich, David; Queloz, Didier; Seager, Sara; Gilliland, Ronald; Chaplin, William J.; et al. (June 2015). "Hubble Space Telescope search for the transit of the Earth-mass exoplanet Alpha Centauri Bb". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 450 (2): 2043–2051. arXiv:1503.07528. Bibcode:2015MNRAS.450.2043D. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv673. S2CID 119162954.

- ^ Aron, Jacob. "Twin Earths may lurk in our nearest star system". New Scientist. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Anglada-Escudé, Guillem; Amado, Pedro J.; Barnes, John; et al. (2016). "A terrestrial planet candidate in a temperate orbit around Proxima Centauri". Nature. 536 (7617): 437–440. arXiv:1609.03449. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..437A. doi:10.1038/nature19106. PMID 27558064. S2CID 4451513.

- ^ a b Suárez Mascareño, A.; Faria, J. P.; Figueira, P.; et al. (2020). "Revisiting Proxima with ESPRESSO". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 639: A77. arXiv:2005.12114. Bibcode:2020A&A...639A..77S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202037745. S2CID 218869742.

- ^ Billings, Lee (12 April 2019). "A Second Planet May Orbit Earth's Nearest Neighboring Star". Scientific American. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Damasso, Mario; Del Sordo, Fabio; et al. (January 2020). "A low-mass planet candidate orbiting Proxima Centauri at a distance of 1.5 AU". Science Advances. 6 (3) eaax7467. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.7467D. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax7467. PMC 6962037. PMID 31998838.

- ^ Benedict, G. Fritz; McArthur, Barbara E. (June 2020). "A Moving Target — Revising the Mass of Proxima Centauri c". Research Notes of the AAS. 4 (6): 86. Bibcode:2020RNAAS...4...86B. doi:10.3847/2515-5172/ab9ca9. S2CID 225798015.

- ^ Gratton, Raffaele; Zurlo, Alice; Le Coroller, Hervé; et al. (June 2020). "Searching for the near-infrared counterpart of Proxima c using multi-epoch high-contrast SPHERE data at VLT". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 638: A120. arXiv:2004.06685. Bibcode:2020A&A...638A.120G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202037594. S2CID 215754278.

- ^ a b Suárez Mascareño, Alejandro; Artigau, Étienne; et al. (29 July 2025). "Diving into the planetary system of Proxima with NIRPS: Breaking the metre per second barrier in the infrared". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 700: A11. arXiv:2507.21751. Bibcode:2025A&A...700A..11S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202553728.

- ^ a b "Why haven't planets been detected around Alpha Centauri?". Universe Today. 19 April 2008. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- ^ Stephens, Tim (7 March 2008). "Nearby star should harbor detectable, Earth-like planets". News & Events. UC Santa Cruz. Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- ^ a b Thebault, P.; Marzazi, F.; Scholl, H. (2009). "Planet formation in the habitable zone of alpha centauri B". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 393 (1): L21 – L25. arXiv:0811.0673. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.393L..21T. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2008.00590.x. S2CID 18141997.

- ^ a b Quintana, E. V.; Lissauer, J. J.; Chambers, J. E.; Duncan, M. J. (2002). "Terrestrial Planet Formation in the Alpha Centauri System". Astrophysical Journal. 576 (2): 982–996. Bibcode:2002ApJ...576..982Q. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.528.4268. doi:10.1086/341808. S2CID 53469170.

- ^ a b Guedes, Javiera M.; Rivera, Eugenio J.; Davis, Erica; Laughlin, Gregory; Quintana, Elisa V.; Fischer, Debra A. (2008). "Formation and Detectability of Terrestrial Planets Around Alpha Centauri B". Astrophysical Journal. 679 (2): 1582–1587. arXiv:0802.3482. Bibcode:2008ApJ...679.1582G. doi:10.1086/587799. S2CID 12152444.

- ^ Billings, Lee. Miniature Space Telescope Could Boost the Hunt for "Earth Proxima". Scientific American (scientificamerican.com) (video).

- ^ Zhao, L.; Fischer, D.; Brewer, J.; Giguere, M.; Rojas-Ayala, B. (January 2018). "Planet detectability in the Alpha Centauri system". Astronomical Journal. 155 (1): 12. arXiv:1711.06320. Bibcode:2018AJ....155...24Z. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa9bea. S2CID 118994786. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ a b Quintana, Elisa V.; Lissauer, Jack J. (2007). "Terrestrial planet formation in binary star systems". In Haghighipour, Nader (ed.). Planets in Binary Star Systems. Springer. pp. 265–284. ISBN 978-90-481-8687-7.

- ^ Barbieri, M.; Marzari, F.; Scholl, H. (2002). "Formation of terrestrial planets in close binary systems: The case of α Centauri A". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 396 (1): 219–224. arXiv:astro-ph/0209118. Bibcode:2002A&A...396..219B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20021357. S2CID 119476010.

- ^ Lissauer, J.J.; Quintana, E.V.; Chambers, J.E.; Duncan, M.J.; Adams, F.C. (2004). "Terrestrial planet formation in binary star systems". Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica. Serie de Conferencias. 22: 99–103. arXiv:0705.3444. Bibcode:2004RMxAC..22...99L.

- ^ a b c Croswell, Ken (April 1991). "Does Alpha Centauri have intelligent life?". Astronomy Magazine. Vol. 19, no. 4. pp. 28–37. Bibcode:1991Ast....19d..28C.

- ^ Gilster, Paul (5 July 2006). "Proxima Centauri and habitability". Centauri Dreams. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ^ a b Kaltenegger, Lisa; Haghighipour, Nader (2013). "Calculating the habitable zone of binary star systems. I. S-type binaries". The Astrophysical Journal. 777 (2): 165. arXiv:1306.2889. Bibcode:2013ApJ...777..165K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/777/2/165. S2CID 118414142.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Planet hunting by numbers" (Press release). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 18 October 2006. Archived from the original on 4 August 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Planet hunting by numbers" (Press release). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 18 October 2006. Archived from the original on 4 August 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

- ^ Mullen, Leslie (2 June 2011). "Rage Against the Dying of the Light". Astrobiology Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d Wiegert, J.; Liseau, R.; Thébault, P.; Olofsson, G.; Mora, A.; Bryden, G.; et al. (March 2014). "How dusty is α Centauri? Excess or non-excess over the infrared photospheres of main-sequence stars". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 563: A102. arXiv:1401.6896. Bibcode:2014A&A...563A.102W. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321887. S2CID 119198201.

- ^ King, Bob (2 February 2022). "See the Sun from other stars". Explore the Night Sky. Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Gilster, Paul (16 October 2012). "Alpha Centauri and the new astronomy". Centauri Dreams. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "The view from Alpha Centauri". Alien Skies. Drew Ex Machina. 28 August 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (12 April 2016). "A visionary project aims for Alpha Centauri, a star 4.37 light-years away". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ O'Neill, Ian (8 July 2008). "How long would it take to travel to the nearest star?". Universe Today.

- ^ Domonoske, Camila (12 April 2016). "Forget Starships: New Proposal Would Use 'Starchips' To Visit Alpha Centauri". NPR. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Starshot". Breakthrough Initiatives. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Reaching for the stars, across 4.37 light-years". The New York Times. 12 April 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (24 August 2016). "One star over, a planet that might be another Earth". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Wenz, John (19 December 2017). "NASA has begun plans for a 2069 interstellar mission". New Scientist. Kingston Acquisitions. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ^ "Do aliens live at Alpha Centauri? NASA wants to send a mission in 2069 to find Out". Newsweek.

- ^ "Alpha Centauri, the star system closest to our sun". Earth & Sky. 16 April 2023. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ Couillard, Sherri. "Sagan Planet Walk Expands to Hawaii". Cornell Daily Sun. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ a b Stableford, Brian (2006). "Star". Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 500–502. ISBN 978-0-415-97460-8.

- ^ a b Westfahl, Gary (2021). "Stars". Science Fiction Literature through History: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 602–604. ISBN 978-1-4408-6617-3.

- ^ Nicholls, Peter; Langford, David (2019). "Generation Starships". In Clute, John; Langford, David; Sleight, Graham (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (4th ed.). Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ Schaaf, Fred (2008). "Alpha Centauri". The Brightest Stars: Discovering the Universe through the Sky's Most Brilliant Stars. Wiley. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-0-471-70410-2.

The first great science-fiction story in which Alpha Centauri played a major role may have been a 1944 tale by A. E. van Vogt. I read it in a much later anthology when I was a kid. The title of the tale—including the sound of that title—was what really filled me with admiration and has stuck with me ever since: "Far Centaurus." Although the name Proxima Centauri basically means "near Centaurus," the title of the story is appropriate because the tale tells of a first spaceship journey that would take many generations to complete—"'Tis for far Centaurus we sail!"

- ^ Stableford, Brian (2004). "Barton, William R.". Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction Literature. Scarecrow Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8108-4938-9.

Alpha Centauri (1997), in which terrorists plague the colony ship which is humankind's last hope

External links

[edit]- "SIMBAD observational data". simbad.u-strasbg.fr.