Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

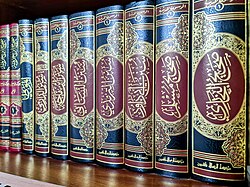

Sunan Abi Dawud

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Part of a series on |

| Hadith |

|---|

|

|

|

Sunan Abi Dawud (Arabic: سنن أبي داود, romanized: Sunan Abī Dāwūd) is the third hadith collection of the Six Books of Sunni Islam. It was compiled by scholar Abu Dawud al-Sijistani (d. 889).[1]

Introduction

[edit]Abu Dawood compiled twenty-one books related to Hadith and preferred those Ahadith (plural of "Hadith") which were supported by the example of the companions of Muhammad. As for the contradictory Ahadith, he states under the heading of 'Meat acquired by hunting for a pilgrim': "if there are two contradictory reports from the Prophet (SAW), an investigation should be made to establish what his companions have adopted". He wrote in his letter to the people of Mecca: "I have disclosed wherever there was too much weakness in regard to any tradition in my collection. But if I happen to leave a Hadith without any comment, it should be considered as sound, albeit some of them are more authentic than others". The Mursal Hadith (a tradition in which a companion is omitted and a successor narrates directly from Muhammad) has also been a matter of discussion among the traditionists. Abu Dawood states in his letter to the people of Mecca: "If a Musnad Hadith (uninterrupted tradition) is not contrary to a Mursal [Hadith], or a Musnad Hadith is not found, then the Mursal Hadith will be accepted though it would not be considered as strong as a Muttasil Hadith (uninterrupted chain)".

The traditions in Sunan Abu Dawood are divided in three categories. The first category consists of those of the traditions that are mentioned by Bukhari and/or Muslim. The second type of traditions are those which fulfil the conditions of Bukhari or Muslim. At this juncture, it should be remembered that Bukhari said, "I only included in my book Sahih Bukhari authentic traditions, and left out many more authentic ones than these to avoid unnecessary length".

Description

[edit]Abu Dawood collected 500,000 hadith, but included only 4,800 in this collection.[2] Sunnis regard this collection as fourth in strength of their six major hadith collections. It took Abu Dawod 20 years to collect the hadiths. He made a series of journeys to meet most of the foremost traditionists of his time and acquired from them the most reliable hadiths, quoting sources through which it reached him. Since the author collected hadiths which no one had ever assembled together, his sunan has been accepted as a standard work by scholars from many parts of the Islamic world,[3] especially after Ibn al-Qaisarani's inclusion of it in the formal canonization of the six major collections.[4][5][6]

Abu Dawood started traveling and collecting ahadeeth at a young age. He traveled to many places in the middle east, including Egypt, Iraq, and Syria. Abu Dawood also studied under Imam Ahmad Ibn Hanbal.[7]

Contents

[edit]Editor, Muhammad Muhyiddin Abd al-Hamid's 1935, Cairo publication, in 4 volumes, provides the standard topical classification of the hadith Arabic text.[8] Sunan Abu Dawood is divided into 43 'books'.[9][10][11]

- purification (kitab al-taharah)

- prayer (kitab al-salat)

- the book of the prayer for rain (kitab al-istisqa)

- prayer (kitab al-salat): detailed rules of law about the prayer during journey

- prayer (kitab al-salat): voluntary prayers

- prayer (kitab al-salat): detailed injunctions about ramadan

- prayer (kitab al-salat): prostration while reciting the qur'an

- prayer (kitab al-salat): detailed injunctions about witr

- zakat (kitab al-zakat)

- the book of lost and found items

- the rites of hajj (kitab al-manasik wa'l-hajj)

- marriage (kitab al-nikah)

- divorce (kitab al-talaq)

- fasting (kitab al-siyam)

- jihad (kitab al-jihad)

- sacrifice (kitab al-dahaya)

- game (kitab al-said)

- wills (kitab al-wasaya)

- shares of inheritance (kitab al-fara'id)

- tribute, spoils, and rulership (kitab al-kharaj, wal-fai' wal-imarah)

- funerals (kitab al-jana'iz)

- oaths and vows (kitab al-aiman wa al-nudhur)

- commercial transactions (kitab al-buyu)

- wages (kitab al-ijarah)

- the office of the judge (kitab al-aqdiyah)

- knowledge (kitab al-ilm)

- drinks (kitab al-ashribah)

- foods (kitab al-at'imah)

- medicine (kitab al-tibb)

- divination and omens (kitab al-kahanah wa al-tatayyur)

- the book of manumission of slaves

- dialects and readings of the qur'an (kitab al-huruf wa al-qira'at)

- hot baths (kitab al-hammam)

- clothing (kitab al-libas)

- combing the hair (kitab al-tarajjul)

- signet-rings (kitab al-khatam)

- trials and fierce battles (kitab al-fitan wa al-malahim)

- the promised deliverer (kitab al-mahdi)

- battles (kitab al-malahim)

- prescribed punishments (kitab al-hudud)

- types of blood-wit (kitab al-diyat)

- model behavior of the prophet (kitab al-sunnah)

- general behavior (kitab al-adab)

Translations

[edit]Sunan Abu Dawood has been translated into numerous languages. The Australian Islamic Library has collected 11 commentaries on this book in Arabic, Urdu and Indonesian.[12]

Arabic commentaries & annotations

[edit]- Maʿālim as-Sunan Sharḥ Sunan Abī Dāwūd, by Imām Abū Sulaymān Ḥamd ibn Muḥammad al-Khaṭṭābī (d. 388 AH). It is published by Muʾassasat ar-Risālah Nāshirūn in four volumes with the taḥqīq (research) of Saʿd ibn Najdat ʿUmar.[13]

- At-Tawassuṭ al-Maḥmūd fī Sharḥ Sunan Abī Dāwūd, by Imām Walī ad-Dīn Ibn al-Irāqī (d. 826 AH). It was recently published by Muʾassasah ʿIlm li Iḥyā ’t-Turāth in two volumes with the taḥqīq (research) of ʿAbd al-ʿĀṭī Muḥyī ash-Sharqāwī .

- Sharḥ Sunan Abī Dāwūd by Imām Shihāb ad-Dīn Abū ’l-ʿAbbās Aḥmad ibn Ḥusayn ibn Raslān (d. 844 AH). It is published by Dār al-Falāḥ in twenty volumes.

- Sharḥ Sunan Abī Dāwūd, by Imām Maḥmūd ibn Aḥmad Badr ad-Dīn al-ʿAynī (d. 855 AH). It is published by Maktabat ar-Rushd in four volumes with the taḥqīq (research) of Abū ’l-Mundhir Khālid ibn Ibrāhīm al-Misrī.

- Fatḥ al-Wadūd bi Sharḥ Sunan Abī Dāwūd, by Imām Abū ’l-Ḥasan Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Hādī as-Sindī (d. 1138 AH). It is published by Jāʾizah Dubai ad-Dawliyyah li ’l-Qurʾān al-Karīm in eight volumes with the taḥqīq (research) of Aḥmad Jāsim al-Muḥammad.

- Mirqāt as-Ṣuʿūd ilā Sunan Abī Dāwūd, by Imām Jalāl ad-Dīn as-Suyūṭī (d. 911 AH). It is published by Dār Ibn-Ḥazm in three volumes.

- Badhl Al-Majhud Fi Hall Abi Dawud by Khalil Ahmad Saharanpuri (d. 1346 AH). It is published by Dār al-Bashāʾir al-Islāmiyyah in fourteen volumes, with the annotations of Mawlānā Zakariyyā Kandhlawī and the taḥqīq (research) of Dr. Taqi ad-Dīn an-Nadwī.[14]

Urdu commentaries & annotations

[edit]Source:[15]

- Inʿām al-Maʿbūd li Ṭālibāt Sunan Abī Dāwūd, by Mawlānā Maḥbūb Aḥmad. It is published by Maktabat al-ʿIlm and is available online.

- Khayr al-Maʿbūd Sharḥ Sunan Abī Dāwūd, by Mawlānā Ṣūfī Muhammad Sarwar. It is published by Idārah Taʾlifāt Ashrafiyyah and is available online.

- Ad-Durr al-Manḍūd ʿalā Sunan Abī Dāwūd, by Mawlānā Muḥammad ʿĀqil. It is published by Maktabat ash-Shaykh in six volumes and is available online.

- As-Samḥ al-Maḥmūd fī Ḥal Sunan Abī Dāwūd, by Muftī Muḥammad ʿAbd ar-Razzāq Qāsmī. It is published by Zakariyyā Book Depot and is available online.

- Falāḥ wa Behbūd Sharḥ Abū Dāwūd, by Mawlānā Muḥammad Ḥanīf Gangohī. It is published by Maktabah Imdādiyyah, Multan, in two volumes and is available online.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jonathan A.C. Brown (2007), The Canonization of al-Bukhārī and Muslim: The Formation and Function of the Sunnī Ḥadīth Canon, p.10. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-9004158399. Quote: "We can discern three strata of the Sunni hadith canon. The perennial core has been the Sahihayn. Beyond these two foundational classics, some fourth/tenth-century scholars refer to a four-book selection that adds the two Sunans of Abu Dawood (d. 275/889) and al-Nasa'i (d. 303/915). The Five Book canon, which is first noted in the sixth/twelfth century, incorporates the Jami' of al-Tirmidhi (d. 279/892). Finally the Six Book canon, which hails from the same period, adds either the Sunan of Ibn Majah (d. 273/887), the Sunan of al-Daraqutni (d. 385/995) or the Muwatta' of Malik b. Anas (d. 179/796). Later hadith compendia often included other collections as well.' None of these books, however, has enjoyed the esteem of al-Bukhari's and Muslim's works." Archived 2018-01-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mohammad Hashim Kamali (2005). A Textbook of Hadith Studies: Authenticity, Compilation, Classification and Criticism of Hadith, p. 39. The Islamic Foundation

- ^ "Various Issues About Hadiths". www.abc.se. Archived from the original on 2012-10-16. Retrieved 2006-03-12.

- ^ Ignác Goldziher, Muslim Studies, vol. 2, pg. 240. Halle, 1889-1890. ISBN 0-202-30778-6

- ^ Scott C. Lucas, Constructive Critics, Ḥadīth Literature, and the Articulation of Sunnī Islam, pg. 106. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2004.

- ^ Ibn Khallikan's Biographical Dictionary, translated by William McGuckin de Slane. Paris: Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland. Sold by Institut de France and Royal Library of Belgium. Vol. 3, pg. 5.

- ^ "About - Sunan Abi Dawud - Sunnah.com - Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)". sunnah.com. Archived from the original on 2021-05-01. Retrieved 2021-05-02.

- ^ Hadith and the Quran, Encyclopedia of the Quran, Brill

- ^ "Abu Dawud". hadithcollection.com. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved Jun 27, 2019.

- ^ "Sunan Abi Dawud". sunnah.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2019. Retrieved Jun 27, 2019.

- ^ "All books and chapters of sunan abu dawood". www.islamicfinder.org. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved Jun 27, 2019.

- ^ "Sunan Abu Dawood". AUSTRALIAN ISLAMIC LIBRARY. Archived from the original on 2021-04-30. Retrieved 2014-10-31.

- ^ "The Commentaries of the Six Canonical Books of Ḥadīth – Ulum al-Hadith".

- ^ "The Commentaries of the Six Canonical Books of Ḥadīth – Ulum al-Hadith".

- ^ "The Commentaries of the Six Canonical Books of Ḥadīth – Ulum al-Hadith".

- ^ "The Commentaries of the Six Canonical Books of Ḥadīth – Ulum al-Hadith".

External links

[edit] Arabic Wikisource has original text related to this article: Sunan Abu Dawud

Arabic Wikisource has original text related to this article: Sunan Abu Dawud

Sunan Abi Dawud

View on GrokipediaSunan Abi Dawud is a foundational collection of prophetic hadiths in Sunni Islam, compiled by the scholar Abū Dāwūd Sulaymān ibn al-Ashʿath al-Sijistānī (202–275 AH / c. 817–889 CE), who was born in Sijistan and traveled extensively to gather traditions from masters in Iraq, Hijaz, and Syria.[1][2]

As the third of the six canonical hadith compilations known as Kutub al-Sittah, it emphasizes hadiths pertinent to Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) and practical law, distinguishing it from collections focused more on general narrations.[1][3]

Abu Dawud sifted through approximately 500,000 hadiths he encountered, selecting around 4,800 for inclusion based on their evidentiary strength and relevance, while explicitly noting instances of weaker (daʿīf) reports where no superior alternatives contradicted the ruling they supported.[3][4]

Organized into topical books on worship, transactions, and penalties, the Sunan prioritizes actionable sunnah over verbal reports alone, earning approval from contemporaries like Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal and enduring as a key reference for deriving legal precepts despite containing a mix of authentic (ṣaḥīḥ) and good (ḥasan) hadiths alongside the flagged weaker ones.[3][5]

Author and Compilation

Biography of Abu Dawud al-Sijistani

Abū Dāwūd Sulaymān ibn al-Ashʿath al-Sijistānī, of the Arab al-Azdī tribe, was born in 202 AH (817–818 CE) in Sijistān, a province in the eastern Abbasid Caliphate encompassing parts of modern-day eastern Iran and western Afghanistan.[1][6] Raised in this frontier region, he began his pursuit of religious knowledge at a young age, focusing on the science of hadith transmission amid the scholarly networks of the early Abbasid era.[1] From adolescence, al-Sijistānī undertook extensive journeys across the Islamic world to study under leading hadith authorities, reaching Baghdad by 220 AH at approximately age 18 and later visiting the Levant in 222 AH, as well as Iraq, the Hijaz, al-Sham (Syria), Egypt, Khurasan, Nishapur, and the Arabian Peninsula.[1][6] He narrated from around 300 sheikhs, including prominent figures such as Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal, with whom he maintained extended companionship, Yabyā ibn Maʿīn, and Quṭaybah ibn Saʿīd.[1][6] These travels underscored his dedication to verifying chains of narration and textual reliability through direct audition from multiple sources.[1] Regarded as a leading muḥaddith (hadith specialist) and faqīh (jurisprudent) of the third century AH, al-Sijistānī earned praise for his mastery in memorization, comprehension, and critical evaluation of prophetic traditions, particularly those bearing juristic implications.[1][7] He resided primarily in Basra later in life, where he taught generations of scholars until his death on 16 Shawwāl 275 AH (889 CE) at age 73, and was buried there beside Sufyān al-Thawrī.[1][6]Historical Context of Compilation

The compilation of Sunan Abi Dawud occurred in the late third century AH (circa 250–270 AH / 864–884 CE), during the Abbasid Caliphate's era of scholarly flourishing, when systematic hadith collections proliferated to codify Prophetic traditions for legal and doctrinal use. This period followed the completion of Sahih al-Bukhari by Muhammad ibn Ismail al-Bukhari (d. 256 AH / 870 CE) and Sahih Muslim by Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj (d. 261 AH / 875 CE), major works emphasizing authenticity through rigorous chains of transmission (isnad). Abbasid patronage, including caliphal support for scholarly institutions in Baghdad and Basra, facilitated such endeavors amid a broader movement to organize the Sunnah against the backdrop of expanding Islamic jurisprudence following the establishment of the four Sunni madhabs.[8][2] A key impetus was the surge in hadith fabrication, exacerbated by sectarian tensions like Shi'a-Sunni divides and political rivalries during Abbasid internal strife, including regional revolts and caliphal power struggles. Scholars documented widespread forgery for ideological advancement, personal gain, or to bolster factional claims, necessitating selective compilations to filter authentic reports from a vast, potentially corrupted corpus. Abu Dawud al-Sijistani (d. 275 AH / 889 CE), having traveled extensively across the Islamic world to gather narrations, responded by prioritizing traditions with practical utility, reflecting the era's demand for reliable evidence in fiqh amid these challenges.[9][10] Abu Dawud explicitly framed his work as a concise supplement to the Sahihayn (Bukhari and Muslim), stating in the Sunan's introduction that he reviewed some 500,000 hadiths but selected only around 4,800—focusing on those most relevant to jurisprudential rulings—after verifying their chains and content. This approach addressed the need for accessible legal precedents without exhaustive comprehensiveness, aligning with contemporaries' efforts to combat dilution of the Sunnah through targeted preservation.[11][12][13]Methodology and Selection Process

Abu Dawud al-Sijistani undertook extensive travels across regions including Khurasan, Iraq, the Hijaz, Syria, and Egypt from approximately 835 to 856 CE to gather hadiths directly from primary narrators and scholars, spanning over two decades of rigorous fieldwork to verify chains of transmission (isnad).[14] This process involved compiling around 500,000 narrations, from which he selected approximately 4,800 for inclusion in his Sunan, prioritizing those with utility for juristic rulings (ahkam) and brevity over exhaustive coverage, often limiting chapters to one or two exemplars even when more existed.[15][16] He rejected the vast majority lacking multiple corroborations (mutaba'at) or clear relevance to established fiqh principles, aiming for a concise reference work rather than a comprehensive repository.[17] In curating the collection, Abu Dawud emphasized verification through robust isnad, favoring connected chains (musnad) over disconnected ones (mursal) unless no alternatives existed, while excluding reports from abandoned narrators (matruk al-hadith).[18] He assessed the text (matn) for consistency with the Quran and corroborated sunnah, avoiding rare or anomalous (gharib) hadiths as primary proof and steering clear of abrogated or uncorroborated reports without supporting evidence.[18] Famous (mashhur) narrations were preferred for their reliability and prevalence among early authorities.[18] Abu Dawud incorporated sahih (sound) and hasan (fair) hadiths as core content but also included some da'if (weak) or munkar (improbable) ones when they addressed gaps in legal topics, explicitly flagging weaknesses in commentary and offering stronger alternatives where available, such as stating, "any hadith in my book that contains a severe weakness, then I have explained it."[18] This approach balanced comprehensiveness in fiqh with transparency about evidential limitations, distinguishing his Sunan from stricter collections by noting exceptions rather than omitting them outright.[3]Content and Organization

Structure into Books and Chapters

Sunan Abi Dawud organizes its hadiths topically into books (kitab), reflecting its classification as a sunan-style collection that prioritizes practical guidance on ritual practices and legal prescriptions (ahkam). This arrangement groups narrations by subject matter relevant to Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), such as acts of worship, transactions, and social conduct, distinguishing it from more general compilations. Each book is further subdivided into chapters (bab), which delineate specific rulings or sub-themes within the broader category, facilitating targeted reference for jurists and scholars.[16][19] The collection is divided into 43 books in standard editions, though some variants extend to 52 depending on the inclusion of additional subdivisions or editorial preferences.[16][20] Prominent books include Kitab al-Taharah (Book of Purification), addressing ritual cleanliness; Kitab al-Salat (Book of Prayer), detailing obligatory and supererogatory prayers; Kitab al-Nikah (Book of Marriage), covering matrimonial contracts and rights; Kitab al-Jihad (Book of Jihad), on military expeditions and related ethics; and Kitab al-Adab (Book of Manners), outlining interpersonal conduct. For example, Sunan Abi Dawud 4703 from Kitab al-Adab (Book of General Behavior) narrates: Arabic: حَدَّثَنَا مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ الْمُثَنَّى، حَدَّثَنَا مُحَمَّدُ بْنُ جَعْفَرٍ، حَدَّثَنَا شُعْبَةُ، عَنْ قَتَادَةَ، عَنْ أَنَسٍ، أَنَّ النَّبِيَّ صلى الله عليه وسلم قَالَ " لاَ يُؤْمِنُ أَحَدُكُمْ حَتَّى يُحِبَّ لأَخِيهِ مَا يُحِبُّ لِنَفْسِهِ " . English: Narrated Anas: The Prophet (ﷺ) said: None of you will have faith till he wishes for his (Muslim) brother what he likes for himself. This hadith is graded Sahih.[21] This fiqh-oriented structure emphasizes actionable rulings over theological exposition or ethical anecdotes, aligning with Abu Dawud's intent to compile traditions pertinent to daily religious observance and legal application.[16][22] Unlike broader hadith works such as Sahih al-Bukhari or Sahih Muslim, Sunan Abi Dawud omits a dedicated book on faith (iman), as its scope narrows to sunan—the normative practices and legal derivations—without redundant coverage of doctrinal foundations already established in prior authoritative collections. The hadiths within this framework are presented concisely, often excerpted or summarized to highlight prescriptive elements, resulting in a more compact corpus compared to the expansive narratives in Sahih Muslim. Chapters within books typically sequence hadiths to build from general principles to nuanced applications, aiding systematic study of ahkam across worship (ibadat), family law, and penal codes.[23]Hadith Corpus: Quantity, Types, and Focus

Sunan Abi Dawud comprises 4,800 hadiths, meticulously selected by its compiler from an estimated 500,000 narrations he reviewed during his travels and studies. This figure accounts for unique reports alongside variants of the same tradition, with the total entries sometimes enumerated as 5,274 when including repetitions across chapters.[5][24][15] The corpus emphasizes marfu' hadiths—narrations directly traced to the Prophet Muhammad—focusing on fiqh-related matters such as inheritance laws, contractual obligations, and hudud punishments to furnish practical sunnah for daily observance and judicial application. This selection prioritizes actionable prophetic guidance over biographical or historical anecdotes, aligning with the Sunan's utility in resolving legal ambiguities in Islamic jurisprudence.[25][26] Hadiths within the collection span qawli (prophetic sayings), fi'li (prophetic actions), and taqriri (prophetic tacit approvals), underscoring a pragmatic orientation toward juristic evidence rather than exhaustive narration. It incorporates some gharib (rare or uniquely transmitted) hadiths for scholarly completeness, though these are typically subordinated to parallel chains with broader corroboration where such exist.[27][28]Authenticity Assessment

Abu Dawud's Criteria for Inclusion

Abu Dawud detailed his selection standards in an epistle to the residents of Makkah, emphasizing a rigorous evaluation of both chains of transmission (isnad) and textual content (matn) to compile hadiths pertinent to legal rulings (ahkam). After examining roughly 500,000 narrations gathered through extensive travel across Islamic regions, he curated approximately 4,800 hadiths focused on actionable sunnah, augmented by about 600 mursal reports where fully connected (muttasil or musnad) alternatives were unavailable.[18][15] Central to his method was requiring at least one sound (sahih) chain for inclusion, with a preference for well-corroborated reports (mashahir) over isolated or anomalous ones (gharib), which he generally eschewed as primary evidence unless supported by stronger transmissions. He restricted chapters to one or two exemplars per topic for brevity, even amid multiple viable options, and noted fewer than ten instances of preferring a narration from superior transmitters over a nominally sahih but weaker-linked variant. Narrations from discredited (matruk) reporters were outright rejected, as were any deemed fabricated based on inconsistencies in reliability or contradiction with verified sunnah; significant defects in otherwise included hadiths were explicitly flagged, rendering unnoted reports presumptively sound.[18] Abu Dawud accepted mursal hadiths—those omitting a Companion link, narrated directly from the Prophet by a Successor—as supplementary proof solely when no connected chain existed for a ruling, acknowledging their relative inferiority to muttasil transmissions yet valuing their alignment with Quranic principles or juristic utility. This evidential hierarchy prioritized narrations facilitating precise causal inference for shari'ah observance, excluding those lacking practical benefit or exhibiting textual anomalies incompatible with established prophetic practice, thereby subordinating volume to verifiable applicability.[18]Internal Indicators of Weakness

Abu Dawud incorporated internal notations within Sunan Abi Dawud to signal potential weaknesses in specific narrations, reflecting a deliberate transparency in his compilation methodology. In his epistle to the scholars of Mecca, he stated that any hadith containing a severe defect (munkar or otherwise) would be explicitly clarified, while unremarked narrations were deemed sahih (sound) according to his judgment.[18] He further distinguished gharib (singular or odd) hadiths, noting they should not serve as primary proof due to their isolated chains, which inherently carry risks of error or lack of corroboration.[18] This practice extended to including mursal (incomplete chain) and mudallas (concealed defect) reports when no stronger alternatives existed, particularly for subsidiary topics, allowing users to weigh reliability contextually. Explicit examples of such markings appear throughout the collection. For instance, in hadith 5271 on general behavior, Abu Dawud commented: "Muhammad b. Hasan is obscure, and this tradition is weak," directly attributing the flaw to a narrator's obscurity. Similar notations occur in sections on eschatology (Kitab al-Malahim) and minor rituals, where he highlighted gharib chains or cross-referenced parallels in more rigorous collections like Sahih al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim for corroboration, underscoring the narration's tentative status.[18] These indicators, though applied to a minority—fewer than ten severe cases with dual chains noted by Abu Dawud himself—facilitate discernment of potentially weaker reports useful for non-binding evidence, such as virtues (fada'il al-a'mal), without endorsing them as authoritative.[18] This self-critical embedding of reservations contrasts with collections lacking such overt qualifiers, enabling subsequent scholars and practitioners to navigate the corpus with awareness of inherent limitations rather than assuming uniform strength.[18]Scholarly Classifications and Gradings

Post-compilation assessments of Sunan Abi Dawud by hadith specialists focused on systematic evaluation of transmission chains (isnad) and content (matn) to determine authenticity levels, employing methodologies independent of Abu Dawud's own selections. These efforts prioritized scrutiny of narrator trustworthiness via jarh wa ta'dil (biographical criticism and validation), verification of uninterrupted chains (muttasil), and identification of textual deviations (shudhudh) or inconsistencies with corroborated reports from higher-standard collections like the Sahihayn. Such classifications distinguished sahih (authentic), hasan (good), and da'if (weak) hadiths, often cross-referencing with biographical compendia like Tahdhib al-Kamal.[29][30] Early classifiers including Ibn al-Qaisarani (d. 507 AH/1108 CE) rated approximately 4,000 hadiths as sahih or hasan, with around 500 identified as da'if, reflecting a high overall reliability despite inclusions of weaker reports for scholarly note. Al-Mizzi (d. 742 AH/1341 CE) corroborated this in his documentation, emphasizing the collection's alignment with rigorous standards through extensive narrator analysis. These gradings underscored that while not all met the stringent thresholds of Bukhari and Muslim—due to occasional reliance on less-vetted transmitters—the bulk withstood scrutiny via supporting evidences (shawahid) and parallel transmissions (mutaba'at).[30] In modern verifications, such as those in Tahdhib al-Sunan, roughly 10% of the corpus (out of approximately 4,800 hadiths) is deemed weak, with the remainder classified as acceptable for jurisprudence when corroborated. Muhammad Nasir al-Din al-Albani (d. 1999 CE) further authenticated many via Silsilah al-Sahihah, strengthening chains through auxiliary evidences and rejecting anomalies based on empirical matn-isnad harmony. Classical verifiers (muhaqqiqun) estimated about 80% conformity to Sahihayn criteria, prioritizing causal consistency over isolated chains.[31][30]Scholarly Reception and Criticisms

Praise from Classical Authorities

Al-Tirmidhi (d. 279 AH/892 CE), a contemporary of Abu Dawud, valued the Sunan for its utility in deriving jurisprudential rulings, frequently referencing its narrations in his own Jami' while grading them for fiqh applications.[32] Al-Nasa'i (d. 303 AH/915 CE), who studied directly under Abu Dawud, incorporated and supplemented material from the Sunan in his own collection, indicating reliance on its structured legal hadiths as a foundational source.[7] Ad-Dhahabi (d. 748 AH/1348 CE) praised Abu Dawud as a leading authority in hadith and fiqh, likening his scholarly stature and piety to that of Ahmad ibn Hanbal, which extended to esteem for the Sunan's methodical selection of over 4,800 narrations focused on actionable sunnah.[7] Similarly, Abu Hatim al-Razi (d. 277 AH/890 CE) lauded Abu Dawud's preeminence in fiqh, knowledge, and memorization, underscoring the collection's role in preserving concise, practical hadiths essential for madhabs.[7] The Sunan's integration into the Kutub al-Sittah canon, formalized by scholars like Ibn al-Athir (d. 630 AH/1233 CE) in works such as Jami' al-Usul, affirmed its status for its emphasis on legal hadiths, distinguishing it as a vital complement to the Sahihayn despite selective inclusions.[15] This empirical acceptance is evidenced by its widespread teaching in Abbasid-era institutions and citation in early fatwas, reflecting classical consensus on its indispensable value for jurisprudential derivation.[15]Criticisms of Reliability and Content

Scholars such as al-Dhahabi (d. 1348 CE) graded a substantial number of hadiths in Sunan Abi Dawud as da'if (weak), estimating hundreds among its approximately 4,800 narrations, often due to interrupted chains (muqta'), unknown narrators, or inconsistencies in matn (text).[33] Abu Dawud himself flagged some weaknesses in his introductions to specific hadiths, acknowledging reliance on solitary chains (ahad) where stronger corroboration was absent, yet critics contend this approach permitted insufficient scrutiny for rulings on sensitive matters like apostasy penalties—such as narrations prescribing execution for leaving Islam—or gender-specific obligations, where da'if reports have occasionally shaped juristic opinions despite evidentiary thresholds demanding rigor comparable to Sahih collections.[5] Orientalist Ignaz Goldziher (d. 1921 CE) extended skepticism to Sunan Abi Dawud within his broader analysis of hadith literature, arguing that 3rd-century AH (9th-century CE) compilations bore risks of retroactive fabrication in isnad (chains) to retrojustify evolving legal and sectarian positions, as evidenced by the exponential growth in reported hadiths—from scant early attestations to tens of thousands by Abu Dawud's era—undermining claims of pristine preservation.[34] Goldziher's critique, while influenced by 19th-century Western historicism potentially underestimating memorization capacities, aligns with empirical patterns of oral corpora expanding via adaptive retellings, as seen in parallel traditions; however, Islamic scholars counter that isnad scrutiny mitigated but did not eliminate such vulnerabilities.[35] A specific instance of contention is hadith 4449, narrating the Prophet placing a Torah scroll on a cushion and declaring, "I believe in thee and in Him Who revealed it," which some interpret as affirming the scripture's integrity, clashing with later doctrines of tahrif (alteration); graded da'if by multiple authorities due to narrators like Hisham ibn Sa'd exhibiting muddled transmissions, it exemplifies unresolved tensions between apparent historical claims and doctrinal consistency.[36] [37] These reliability issues trace causally to the mechanics of pre-print oral transmission in early Islamic society, where reliance on human memory over generations invited inadvertent errors, conflations from analogous events, or subtle influences from jurisprudential needs—phenomena observable in other unwritten traditions—rather than systemic fraud, though the absence of contemporaneous written checks amplified propagation risks and mandates rigorous corroboration against the Quran or mutawatir (mass-transmitted) reports for doctrinal weight.[38]Comparisons to Other Major Collections

Sunan Abi Dawud employs less rigorous inclusion criteria than Sahih al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim, the two most authoritative collections in Sunni Islam, which prioritize exclusively sahih (authentic) hadiths with near-unanimous scholarly consensus on their soundness, estimated at over 99% reliability.[39] In contrast, Sunan Abi Dawud incorporates approximately 4,800 hadiths selected from 500,000 narrations, with scholarly gradings indicating around 55-60% strictly sahih, 20% hasan (good), and the remainder da'if (weak), though Abu Dawud explicitly flagged potentially weak ones for verification, resulting in an overall 80-90% usable for jurisprudence when combining sahih and hasan.[15][40] This approach sacrifices some thematic depth and repetition found in al-Bukhari's 7,275 hadiths for brevity and focus on actionable legal traditions (ahadith al-ahkam), positioning it as a supplementary source rather than a primary benchmark of authenticity.[5] Compared to Jami' at-Tirmidhi and Sunan al-Nasa'i, both later Sunan collections emphasizing fiqh-oriented hadiths, Sunan Abi Dawud offers greater comprehensiveness in rulings on worship and transactions by including rarer (gharib) narrations absent in the Sahihayn, enabling broader interpretive scope but requiring cross-verification due to elevated weak elements.[41] At-Tirmidhi, compiled around 279 AH, integrates juristic opinions (fiqh al-muhadith) alongside gradings, while al-Nasa'i (d. 303 AH) prioritizes chain discrepancies and abridgment for purity; Abu Dawud's earlier effort (completed 273 AH) thus fills a niche in concise, fiqh-centric compilation without extensive commentary, though it demands more scholarly scrutiny for gharib hadiths.[42] Unlike Muwatta Malik, compiled by Malik ibn Anas (d. 179 AH/795 CE) as an early Medinan work blending hadiths with the author's juristic opinions ('amal ahl al-Madinah) and roughly 1,700 narrations, Sunan Abi Dawud adheres strictly to prophetic traditions via isnad (chains of transmission) without integrating regional practices or personal fiqh derivations.[43] This pure hadith focus distinguishes it within the Sihah Sittah (the six canonical collections), where it ranks third after al-Bukhari and Muslim, serving as supplementary evidence for rulings when primary sahih sources are insufficient, rather than a holistic legal manual like the Muwatta.[44] The inclusion of gharib hadiths in Sunan Abi Dawud empirically broadens evidentiary base for diverse legal contexts but heightens the burden of authentication compared to the more uniform reliability of peer collections.[45]| Collection | Approx. Hadith Count | Est. Sahih/Hasan % | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sahih al-Bukhari | 7,275 | ~99% sahih | Comprehensive authenticity, themes |

| Sahih Muslim | 7,563 | ~99% sahih | Parallel authentication, systematics |

| Sunan Abi Dawud | 4,800 | 80-90% | Fiqh rulings, brevity, gharib inclusion |

| Jami' at-Tirmidhi | 3,956 | ~85% | Fiqh gradings, opinions |

| Sunan al-Nasa'i | 5,700 | ~90% | Chain purity, abridgment |